Abstract

T-cell homing to secondary lymphoid tissues generally depends on chemokine-induced firm adhesion in high endothelial venules (HEVs) and is primarily mediated through the CC chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) on lymphocytes. The CCR7 ligand designated CCL21 is considered the most important trigger because it appears constitutively expressed by murine HEVs. Surprisingly, when we analyzed human tissues, no CCL21 mRNA could be detected in HEVs. In fact, CCL21 mRNA was only expressed in extravascular T-zone cells and lymphatics, whereas immunostaining revealed CCL21 protein within HEVs. This suggests that T-cell recruitment to human lymphoid tissues depends on the transcytosis of lymphoid chemokines through HEV cells because there is at present no evidence of alternative chemokine production in these cells that could explain the attraction of naive T lymphocytes.

Introduction

Continuous migration of T cells into organized lymphoid tissue and back into the blood circulation is essential for immune surveillance. T-cell recruitment in most peripheral lymphoid organs occurs through the walls of high endothelial venules (HEVs) in a stepwise sequence of interactions between lymphocytes and HEV cells,1 and CC chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7)–mediated triggering of firm vascular adhesion is essential for successful extravasation.2,3 Furthermore, the CCR7 ligand designated CCL21 (also named TCA-4, SLC, Exodus-2, and 6Ckine) has been regarded as the main inductor of T-cell arrest since its identification in mice, primarily because it is constitutively and highly expressed, both at the mRNA and the protein level, by HEVs in murine lymphoid organs.4-6

In recent gene-profiling studies of freshly isolated human HEV cells, however, CCL21 mRNA has been difficult to detect. Lacorre et al7 found that the CCL21 hybridization signal on DNA arrays was below the cut-off value for significant expression, and Palmeri et al8 were unable to detect any CCL21-expressed sequence tags (ESTs) in a cDNA library enriched in HEV-specific transcripts, even after they characterized more than 1000 cDNAs. Furthermore, in situ hybridization performed on human lymphoid tissue (lymph nodes and appendix) revealed CCL21 mRNA in the T-cell zone and at the periphery of B-cell follicles, whereas its expression in HEV cells and other endothelial cells was not clarified.9,10 These uncertainties prompted us to analyze directly the in situ expression pattern of CCL21 in human mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs), tonsils, and Peyer patches (PPs).

Surprisingly, in situ mRNA hybridization performed on sections of these human lymphoid tissues demonstrated transcripts in extrafollicular cells and lymphatic vessels but not in HEVs. Conversely, immunohistochemical staining revealed CCL21 protein in HEV cells and also associated with the reticular network in extrafollicular areas. We have previously shown that the other known CCR7 ligand, designated CCL19 (also named ELC, Exodus-3, and MIP-3β), is subject to vascular transcytosis in human HEVs.11 In addition, animal experiments have demonstrated that when exogenous CCL21 reaches peripheral lymph nodes (PLNs) through afferent lymph, it is transported to the luminal surfaces of HEVs.5 Our present data show that CCL21 is normally not synthesized by human HEVs and, importantly, no alternative chemokine ligand able to attract naive T cells is known to be synthesized by these cells. Transcytosis of lymphoid chemokines through HEVs, therefore, appears to be crucial for constitutive T-cell recruitment to human lymphoid tissues.

Study design

Cryosections of normal human lymphoid tissues were cut serially from various tissue samples, including palatine tonsils (n = 3), MLNs (n = 3), and normal PPs (n = 3) obtained from patients undergoing tonsillectomy or colectomy (because of long-lasting chronic obstipation), respectively. All procedures involving patient material were approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (Health Region South, Oslo, Norway). Cryosections were also cut from murine lymphoid organs (PLNs, MLNs, and PPs) harvested from C57Bl/6N mice (Taconic M&B, Ry, Denmark). Digoxigenin (DIG)–labeled riboprobes were generated from the coding regions of cDNA for human (339 base pair [bp]) and murine (501 bp) CCL21 with the DIG RNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) using the following primers to generate cDNA templates: human CCL21, 5′-GCTCTGAGCCTCCTTATCCTG-3′ and 5′-GCCCTTTCCTTTCTTGCC -3′; murine CCL21, 5′-CAACCACAATCATGGCTCAG-3′ and 5′-TAGCTCCCTCTTTGCCTGTG-3′. Hybridization, detection of the hybridized probe, immunofluorescence staining, image acquisition, and image processing were performed as previously described.12-14 Primary antibodies for immunostaining were: anti–human CCL21 (MAB366 and AF366; R&D Systems, Oxon, United Kingdom), MECA-79 (courtesy of E.C. Butcher, Stanford University Medical School, CA), anti–human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) (courtesy of K. Alitalo, Haartman Institute, Helsinki, Finland), and anti–human fibronectin (A0245; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark).

Results and discussion

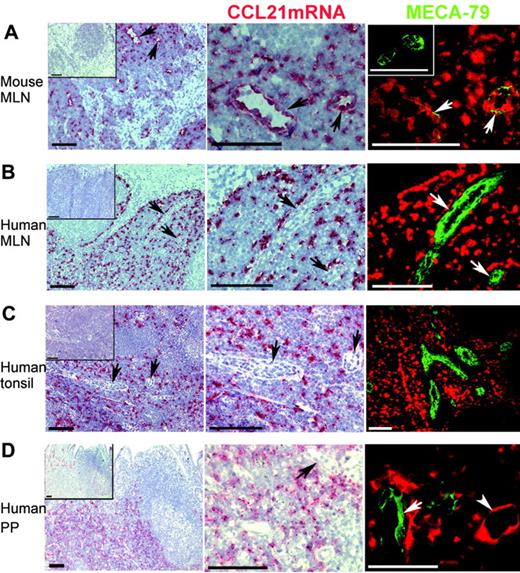

CCL21 mRNA was readily detected by in situ hybridization in the T-cell zone of murine PLNs and PPs (data not shown), as reported by others.4,6 As expected, a similar pattern of CCL21 mRNA expression was seen in murine MLNs (Figure 1A). Higher magnification revealed strong hybridization to endothelial cells (Figure 1A, middle column), and their identity as HEVs (Figure 1A, right column) was confirmed by immunostaining of prehybridized sections with the MECA-79 antibody detecting peripheral lymph node addressin (PNAd).15

In situ hybridization performed on human MLNs, tonsils, and PPs also revealed CCL21 mRNA in the T-cell zone (Figure 1B-D). Surprisingly, however, the CCL21 antisense probe did not hybridize to cells displaying HEV morphology despite abundant hybridization observed in the T-cell zone (Figure 1B-D, middle column). Furthermore, immunostaining of prehybridized sections directly showed the lack of CCL21 transcripts in MECA-79+ HEVs (Figure 1B-D, right column). However, human vessel walls resembling lymphatics expressed CCL21 mRNA (Figure 1D, right column, arrowhead), as we have previously shown for vessels negative for von Willebrand factor in normal peripheral tissue in humans.13 Similarly, lymphatic CCL21 mRNA expression has been reported for wild-type mice4 and mice with the plt mutation.16 It could be argued that HEV expression of CCL21 mRNA was below the detection limit of our protocol; however, because we obtained strong hybridization signals in murine HEVs, the levels of possible mRNAin the human HEVs would at least be comparatively very low.

CCL21 mRNA is not detected in HEVs of normal human lymphoid tissues but is expressed in lymphatic endothelium and perivascular cells. In situ hybridization for CCL21 mRNA (red) and subsequent immunofluorescence staining for peripheral lymph node addressin (PNAd) with the monoclonal MECA-79 antibody (green) in normal mouse and human lymphoid tissues. Insets in left column display negative sense controls. Left and middle columns are light microscopic exposures in which PNAd expression is not visualized. Right column is merged color separation captured with the fluorescence microscope. (A) Numerous HEVs with strong CCL21 mRNA expression are detected in mouse mesenteric lymph node (MLN). HEVs (arrows) in left column are enlarged in the middle and right columns. Because of masking of epitopes by large depositions of biotinyl tyramide/Fast Red substrate at the site of CCL21mRNA, only thin streaks of PNAd expression are seen in these mouse HEVs (right), whereas more extensive PNAd expression is seen in the sense control (inset). (B) Extensive expression of CCL21 mRNA is seen in the T-cell zone of human MLN but is not detectable within HEVs. Negative HEVs (arrows) in left column are enlarged in the middle and right columns. (C) Extensive CCL21 mRNA expression is also seen outside HEVs in the T-cell areas in human tonsil. Negative HEVs (arrows) in the left column are enlarged in the middle column. No CCL21 mRNA is detected in the numerous MECA-79+ HEVs in the T-cell area (right). (D) Human PP with extensive CCL21 mRNA expression in T-cell areas. Vascular structures that express CCL21 mRNA are seen, but those with HEV morphology (arrow) are negative. CCL21 mRNA+ vascular structure with flat endothelium consistent with lymphatic vessel (lower right; arrowhead) is seen close to a MECA-79+ HEV (arrow), which is negative. Bar represents 100 μm except in the lower right panel, where it represents 50 μm.

CCL21 mRNA is not detected in HEVs of normal human lymphoid tissues but is expressed in lymphatic endothelium and perivascular cells. In situ hybridization for CCL21 mRNA (red) and subsequent immunofluorescence staining for peripheral lymph node addressin (PNAd) with the monoclonal MECA-79 antibody (green) in normal mouse and human lymphoid tissues. Insets in left column display negative sense controls. Left and middle columns are light microscopic exposures in which PNAd expression is not visualized. Right column is merged color separation captured with the fluorescence microscope. (A) Numerous HEVs with strong CCL21 mRNA expression are detected in mouse mesenteric lymph node (MLN). HEVs (arrows) in left column are enlarged in the middle and right columns. Because of masking of epitopes by large depositions of biotinyl tyramide/Fast Red substrate at the site of CCL21mRNA, only thin streaks of PNAd expression are seen in these mouse HEVs (right), whereas more extensive PNAd expression is seen in the sense control (inset). (B) Extensive expression of CCL21 mRNA is seen in the T-cell zone of human MLN but is not detectable within HEVs. Negative HEVs (arrows) in left column are enlarged in the middle and right columns. (C) Extensive CCL21 mRNA expression is also seen outside HEVs in the T-cell areas in human tonsil. Negative HEVs (arrows) in the left column are enlarged in the middle column. No CCL21 mRNA is detected in the numerous MECA-79+ HEVs in the T-cell area (right). (D) Human PP with extensive CCL21 mRNA expression in T-cell areas. Vascular structures that express CCL21 mRNA are seen, but those with HEV morphology (arrow) are negative. CCL21 mRNA+ vascular structure with flat endothelium consistent with lymphatic vessel (lower right; arrowhead) is seen close to a MECA-79+ HEV (arrow), which is negative. Bar represents 100 μm except in the lower right panel, where it represents 50 μm.

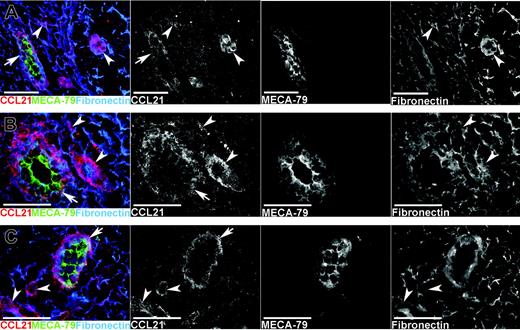

Given the apparent absence of CCL21 mRNA in human HEVs, we next assessed CCL21 protein expression by means of 3-color immunofluorescence staining for CCL21, PNAd (with MECA-79), and the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin, observing prominent CCL21 decoration of MECA-79+ HEVs in MLNs, tonsils, and PPs (Figure 2). Incubation with an irrelevant concentration- and isotype-matched antibody instead of anti-CCL21 gave no staining (not shown). Furthermore, CCL21 appeared to be deposited on extracellular fibrils (fibronectin+) in these tissues (Figure 2, right column) at the sites of lymphatic vessels (VEGFR-3+, data not shown) and elsewhere in the stroma.

The CCL21 colocalization with fibronectin in the T-cell zone was similar to the pattern observed for the lymphoid chemokine CXCL13 in the mantle zone,12 possibly corresponding to the recently identified cortical ridge, a putative interaction site for lymphocytes and dendritic cells.17

The expression pattern of CCL21 in human lymphoid organs, with perivascular synthesis and HEV localization of protein, is highly reminiscent of the other CCR7 ligand, CCL19; we were able to show that CCL19 is transcytosed in HEVs and that it participates in T-cell recruitment from the circulation.11 Interestingly, HEVs also have the capacity to translocate perivascular CCL21 to the lumen.5,11 Therefore, it seems likely that HEVs have a highly active machinery for lymphoid chemokine transcytosis and subsequent presentation.18,19 Candidate endothelial ligands that transport and present chemokines include glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and possibly the Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines (DARC), though the latter shows no affinity for lymphoid chemokines.20

We have previously shown that blood vessels in long-standing chronic inflammatory lesions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis, express CCL21 mRNA.13 In that study, most CCL21+ blood vessels did not exhibit HEV characteristics and were negative for MECA-79 staining. Mechanistic data suggested that endothelial-derived CCL21 could be an important determinant for T-cell extravasation in such inflamed human tissues.13 However, some CCL21+ blood vessels in those tissues stained for MECA-79, and other studies show induction of this marker on a subset of vessels in inflammatory lesions,21 which may contribute to most of the leukocyte recruitment. In contrast to CCL21 mRNA expression in blood vessel in inflammation, our present data imply that the homeostatic trafficking of T cells to human secondary lymphoid tissues is mediated by perivascularly derived CCR7 ligands translocated to the lymphocyte-endothelial interface.

CCL21 protein is expressed in HEVs and is also associated with extracellular fibrils in normal human lymphoid tissues. Single-color separations in black and white and color merges of multicolor immunofluorescence staining for CCL21, PNAd (MECA-79), and fibronectin (see keys on panel). CCL21 immunostaining is seen in HEVs (arrows) in (A) normal mesenteric lymph node, (B) tonsil, and (C) PP. The strongest CCL21 staining in HEVs (arrows) is seen at the basal side, associated with the reticular network around HEVs, whereas MECA-79 staining in HEVs is strongest at the luminal face. CCL21 is also associated with the reticular network outside HEVs (arrowheads) at the sites of other vascular structures resembling lymphatics and elsewhere in the stroma.

CCL21 protein is expressed in HEVs and is also associated with extracellular fibrils in normal human lymphoid tissues. Single-color separations in black and white and color merges of multicolor immunofluorescence staining for CCL21, PNAd (MECA-79), and fibronectin (see keys on panel). CCL21 immunostaining is seen in HEVs (arrows) in (A) normal mesenteric lymph node, (B) tonsil, and (C) PP. The strongest CCL21 staining in HEVs (arrows) is seen at the basal side, associated with the reticular network around HEVs, whereas MECA-79 staining in HEVs is strongest at the luminal face. CCL21 is also associated with the reticular network outside HEVs (arrowheads) at the sites of other vascular structures resembling lymphatics and elsewhere in the stroma.

To conclude, we have identified a species-specific difference in lymphoid chemokine expression. In contrast to murine lymphoid organs in which HEVs produce CCL21 themselves, human HEVs lack detectable CCL21 mRNA. However, CCL21 protein is readily detectable within human HEVs, suggesting that extravascular CCL21 is translocated through HEVs to mediate T-cell trafficking to human lymphoid tissues. Given that there is no other known chemokine ligand synthesized by HEVs to attract naive T cells, translocation of lymphoid chemokines through HEVs appears to be crucial for constitutive T-cell recruitment in humans.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 31, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4353.

Supported by the Research Council of Norway (H.S.C., G.H., P.B.) and the University of Oslo (P.B.). Supported by grants from the Norwegian Cancer Society (E.S.B, G.H., P.B.) and the Anders Jahre's Fund (P.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank the technical staff at LIIPAT for expert technical assistance.