Abstract

Interferons (IFNs) are cytokines with pronounced proinflammatory properties. Here we provide evidence that IFNs also play a key role in decline of inflammation by inducing expression of tristetraprolin (Ttp). TTP is an RNA-binding protein that destabilizes several AU-rich elementcontaining mRNAs including TNFα. By promoting mRNA decay, TTP significantly contributes to cytokine homeostasis. Now we report that IFNs strongly stimulate expression of TTP if a costimulatory stress signal is provided. IFN-induced expression of Ttp depends on the IFNactivated transcription factor STAT1, and the costimulatory stress signal requires p38 MAPK. Within the Ttp promoter we have identified a functional gamma interferon-activated sequence that recruits STAT1. Consistently, STAT1 is required for full expression of Ttp in response to LPS that stimulates both p38 MAPK and, indirectly, interferon signaling. We demonstrate that in macrophages IFN-induced TTP protein limits LPS-stimulated expression of several proinflammatory genes, such as TNFα, IL-6, Ccl2, and Ccl3. Thus, our findings establish a link between interferon responses and TTP-mediated mRNA decay during inflammation, and propose a novel immunomodulatory role of IFNs.

Introduction

Interferons (IFNs) are cytokines that were originally described as polypeptides causing activation of antiviral responses.1 Over the years it became clear that interferons play a major role in immune responses to essentially all infections.2,3 IFNs exert their biological effects by regulating gene transcription. Type II IFN (IFN-γ) induces phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT1 at Tyr701 that causes STAT1:1 dimer formation, nuclear translocation, and DNA binding.4,5 Type I IFNs (eg, IFN-α and IFN-β) induce tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 causing the formation of STAT1:2 heterodimers and STAT1:1 homodimers.4,5 STAT1:2 heterodimers acquire their DNA binding ability by associating with the transcription factor IRF9 to form the transcription complex ISGF3. ISGF3 binds to ISRE elements, whereas STAT1 dimers target GAS elements in the promoters of interferonregulated genes. For full biological activity, the transactivation domain of STAT1 requires phosphorylation at Ser727.6,7 IFNs cause phosphorylation of both Tyr701 and Ser727 residues. p38 MAPK induces Ser727 phosphorylation only, but can enhance STAT1-driven transcription independently of Ser727 phosphorylation.8-11 Thus, STAT1 function and IFN-stimulated gene expression are modulated by p38 MAPK, one of the key inflammationactivated serine kinases. In fact, many inflammation-related genes require both IFNs and p38 MAPK for their maximal stimulation.3,12

One of the major proinflammatory mediators is tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). An acute overproduction or chronically high levels of TNFα cause pathologic conditions such as septic shock or inflammatory arthritis, respectively.13,14 The immune system has developed several mechanisms to limit the production of this potentially harmful cytokine. Regulation of mRNA stability plays a major role in preventing overproduction of TNFα.15 The 3′ end of TNFα mRNA contains AU-rich elements (AREs) that are recognized by a group of ARE-binding proteins regulating mRNA stability.16-18 Gene-targeting experiments provided evidence that tristetraprolin (Ttp) is an anti-inflammatory gene that suppresses TNFα production by stimulating ARE-mediated TNFα mRNA decay.19,20 Mice deficient in TTP display elevated TNFα serum levels resulting in cachexia and inflammatory polyarthritis. Ttp is an immediate-early gene induced by inflammatory stimuli like LPS or TNFα with p38 MAPK playing a key role herein.20,21 TTP is also induced by IL-4 and TGFβ through the activation of the transcription factors STAT6 and SMAD3/SMAD4, respectively.22,23 TTP regulates stability of mRNAs other than TNFα as well, most notably granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and TTP itself.24-26 The biological activity of TTP is regulated by phosphorylation that plays a role in association of TTP with stress granules, the sites of ARE-mediated mRNA decay.21,27-29

Previously we have shown that transcription of Irf1, a known IFN target gene, is synergistically induced by IFN and p38 MAPK signaling.10 In a DNA microarray-based screen we have identified Ttp as another gene synergistically induced by IFN-γ and p38 MAPK. We have characterized a functional GAS element in the Ttp promoter that is capable of recruiting STAT1. Our study shows that STAT1 is required for maximal expression of Ttp after stimulation of macrophages with LPS. LPS-induced expression of Ttp can be further strongly enhanced by cotreatment with IFNs. We further demonstrate that IFN-induced Ttp expression restrains the induction of the proinflammatory genes TNFα, IL-6, Ccl2, and Ccl3. Thus, by amplifying TTP expression IFNs generate a negative feedback that limits inflammatory signals elicited by both IFNs and microbial products.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

p38α–/–, p38α+/+, STAT1–/–, and STAT1+/+ immortalized fibroblasts have been described recently.10,30 Cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Primary bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) were obtained from 8- to 12-week-old mice and cultivated in L cell–derived CSF-1 as reported previously.31 STAT1-deficient mice32 were of mixed 129Sv/CD1 background, and Ttp-deficient19 as well as IFN-β–deficient mice were of C57Bl/6 background. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mouse macrophage line Bac 1.2F5 was grown as described.33 Mouse macrophage line J774 was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS.

Cytokines, reagents, and antibodies

Recombinant IFN-γ (kindly provided by G. Adolf, Boehringer Ingelheim, Austria) was used at 10 ng/mL for the times indicated in figure legends. Recombinant IFN-β was purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany) and used at 200 U/mL. LPS from Salmonella minnesota (Alexis, Lausen, Switzerland) and anisomycin (Sigma, Vienna, Austria) were used at 100 ng/mL for the times specified in figure legends. Antiserum to STAT1 C-terminus (S1) has been described.34 Antibodies to Tyr701-phosphorylated STAT1 (pY701-S1) and phosphorylated p38 (pp38) were from Cell Signaling (NEB, Frankfurt/Main, Germany). Monoclonal antibodies to STAT1 N-terminus (S1-N) and to extracellular signal regulated kinases (panERK) were from BD Transduction Laboratories (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium). p38 antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibody to the C-terminus of TTP was kindly provided by A. R. Clark (Imperial College School of Medicine London, United Kingdom).

Transient transfection and luciferase assays

pGL2 luciferase reporter vectors, pGL2basic and pGL2promoter, were from Promega (Mannheim, Germany). Fragments of the mouse Ttp promoter, size 2 kb (–2025 to +25) and size 194 bp (–2085 to –1891), were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from genomic mouse fibroblast DNA, and cloned into pGL2basic and pGL2promoter to obtain the plasmids pGL-TTP and pGL-TTP-GAS, respectively. Both constructs were verified by sequencing. The 2-kb fragment was amplified using the forward primer 5′-ATCTCGAGGTTACAAGAGAAGGAACCCAA-3′ and reverse primer 5′ATAAGCTTTGTCGGTTCGCAGAAGTCAGG-3′, and inserted into pGL2basic using XhoI and HindIII restriction sites. The 194-bp fragment was amplified using 5′-ACGACGCGTCGGCCCCTCCTTCCCTTCTTTTCC-3′ as forward and 5′-CCCTCGAGGGCATAGGCTGCTGTGGCACGG-3′ as reverse primer and cloned into the pGL2promoter plasmid using MluI and XhoI to obtain the plasmid pGL2-TTP-GAS. Transfections were performed using ExGen500 (Fermentas, St Leon-Rot, Germany). pGL2-TTP together with pEF-Zeo30 was cotransfected into p38α+/+ cells and a bulk culture was established by a 2-week-long selection with 100 μg/mL zeocin. pGL-TTP-GAS was transiently transfected into STAT1+/+ and STAT1–/– fibroblasts. Transfection efficiency was controlled using ecdysone inducible system (Invitrogen, Lofer, Austria) as previously described.10

Luciferase assays were performed in triplicate, according to standard protocols.35

ELISAs

For enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), BMMs were seeded the day before use at 5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well tissue plates. Supernatants were diluted 1:7 in DMEM, and TNFα and IL-6 were assayed in triplicate using Quantikine kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Western blot and electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (EMSA)

Western blot analysis was performed using whole-cell extracts from 2 × 106 BMMs as previously described.34 For EMSA, whole-cell extracts from 5 × 106 Bac 1.2F5 cells were prepared and processed as described.34 Oligonucleotides used in EMSA were as follows: TTP-GAS (fwd 5′-CTAGCGGCTTCCAGGAAGCCCG-3′, rev 5′-GCCGAAGGTCCTTCGGGCGATC-3′) and mutTTP-GAS (fwd 5′-CTAGCGGCTTAAAGGAAGCCCG-3′, rev 5′-GCCGAATTTCCTTCGGGCGATC-3′).

Quantitation of gene expression by quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using nucleo-spin reagent kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Reverse transcription was performed with the Mu-MLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas). The following primers were used: for Hprt, the housekeeping gene used for normalization, HPRT-fwd 5′-GGATTTGAATCACGTTTGTGTCAT-3′ and HPRT-rev 5′-ACACCTGCTAATTTTACTGGCAA-3′; for TTP, TTP-fwd 5′-CTCTGCCATCTACGAGAGCC-3′ and TTP-rev 5′-GATGGAGTCCGAGTTTATGTTCC-3′; for luciferase, Lucfwd 5′-GCAGGTCTTCCCGACGATGA-3′ and Luc-rev 5′-GTACTTCGTCCACAAACACAACTC-3′. Amplification of DNA was monitored by SYBR Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).36 For detection of TNFα, Ccl2, Ccl3, Gbp2, and Cxcl10 Taqman assays from Applied Biosystems (Weiterstadt, Germany) were used.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP)

STAT1-WT fibroblasts (2 × 106) were treated for 30 minutes with 10 ng/mL IFN-γ or left untreated. ChIP was performed using the Upstate Biotechnology protocol with slight modifications.7 Analysis of the immunoprecipitated DNA was performed by PCR using primers for the Ttp promoter (fwd 5′-ATTGGCTGGCTCAGGGATTTGT-3′ and rev 5′-CATAGGCTGCTGTGGCACGG-3′).

Nuclear run-on

Nuclear run-on reactions were performed as previously described,37 with some modifications. Briefly, nuclei were prepared from 8 × 106 cells by lysis in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.1% Nonident P-40, 1 mM DTT), followed by 6 up and down strokes through a 25 G syringe. Nuclei were isolated by centrifugation (500g), and pellets were resuspended in 100 μL glycerol buffer (40% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA). 2x reaction buffer (100 μL containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 300 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, and 1 mM each of ATP, CTP, and GTP), 100 U/μL ribonuclease inhibitor (Sigma), and 3.7 × 106 Bq (100 μCi) 32P-labeled UTP (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA) were added to the nuclei. After incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature and addition of 6 μg DNase I (Sigma) for 10 minutes (at room temperature), RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and ammonium acetate precipitation. Pellets were resuspended in 1 mL ETS hybridization buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA,0.2% SDS, 2x Denhardt, 400 mM NaCl, 200 μg/mL yeast tRNA). cDNA (400 ng per slot) was slot-blotted on a nylon membrane (Perkin Elmer) and UV cross-linked. Membranes were prehybridized for 1 hour in TESS buffer (20 mM TES, pH 7.4, 400 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS, 2x Denhardt, 200 μg/mL yeast tRNA) at 65°C. The prehybridization solution was removed and 1 mL of the labeled RNA was incubated with the membranes at 65°C for 18 hours. Membranes were washed twice in 2x SSC/1% SDS at 60°C and once in 0.1x SSC at room temperature.

Statistical analysis

Data from independent experiments were analyzed using univariate linear regression models and the SPSS program (SPSS, Chicago, IL). For qRT-PCR, untransformed normalized Ct-values, for ELISA, pg/mL were used as raw data. Residuals were plotted, visually inspected, and tested for normality. Design matrices were specified such that the coefficients for the relevant comparisons could be calculated, for example, between the baseline and induced states and between genotypes. Only the significance levels are reported.

Results

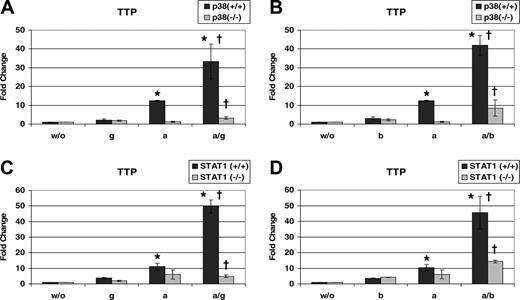

Interferons require STAT1 and activation of p38 MAPK to induce transcription of Ttp

STAT1 is activated by IFNs independently of p38 MAPK, which is, however, able to further enhance STAT1 transcriptional activity.10,11 We employed mouse 16K cDNA microarrays to find genes that are strongly activated only if both STAT1 (by IFN-γ) and p38 MAPK (by anisomycin) are stimulated (data not shown). We identified tristetraprolin (Ttp) to be regulated in the desired way and validated the DNA-microarray data by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Immortalized p38α–/– mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and control MEFs were stimulated with IFN-γ, anisomycin, or both. p38α–/– cells are lacking the p38α isoform, the most abundant of the known p38α, β, γ, and δ isoforms. p38α–/– cells display a very weak p38 activity, which is due to the low expression of the remaining p38 genes.10 The p38α–/– cells have therefore been widely used to evaluate the contribution of p38 MAPK to various biological phenomena.10,11,38 A 1-hour treatment with anisomycin (a p38 MAPK agonist39 ) induced Ttp mRNA levels in p38α+/+ but not in p38α–/– cells (Figure 1A). The requirement for p38 MAPK in expression of Ttp is in agreement with previous studies employing the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203 580.21 Treatment with IFN-γ for 1 hour weakly increased Ttp mRNA in p38α+/+ or p38α–/– fibroblasts. However, a combined treatment with IFN-γ and anisomycin caused a strong synergistic induction of Ttp mRNA in p38α+/+ but not in p38α–/– cells. The level of Ttp mRNA after the double treatment was 3 times higher than that induced by anisomycin alone. The effect was more than additive: the cumulative induction by the single treatments with IFN-γ and anisomycin was 14-fold, whereas the induction by the double treatment was 33-fold. The synergistic induction by the double treatment as well as the effect of p38 MAPK were highly significant (P < .01). Similar results were obtained when IFN-β was used instead of IFN-γ (Figure 1B).

p38 MAPK and STAT1 synergistically increase Ttp mRNA expression. p38α+/+ and p38α–/– MEFs were left untreated (w/o) or treated for 1 hour with IFN-γ (g), anisomycin (a) or both (a/g) (A), or treated with IFN-β (b), anisomycin (a) or both (a/b) (B). STAT1+/+ and STAT1–/–fibroblasts were stimulated as described for panels A and B, respectively (C,D). Total RNA was isolated and Ttp mRNA levels were determined using qRT-PCR. To obtain Ttp mRNA induction, values were normalized to those of untreated cells. Error bars indicate SD. *P < .01 (a/g) or (a/b) versus (a) treatment in +/+ cells; †P < .01 +/+ versus –/–MEFs by univariate linear regression models; n = 3 experiments.

p38 MAPK and STAT1 synergistically increase Ttp mRNA expression. p38α+/+ and p38α–/– MEFs were left untreated (w/o) or treated for 1 hour with IFN-γ (g), anisomycin (a) or both (a/g) (A), or treated with IFN-β (b), anisomycin (a) or both (a/b) (B). STAT1+/+ and STAT1–/–fibroblasts were stimulated as described for panels A and B, respectively (C,D). Total RNA was isolated and Ttp mRNA levels were determined using qRT-PCR. To obtain Ttp mRNA induction, values were normalized to those of untreated cells. Error bars indicate SD. *P < .01 (a/g) or (a/b) versus (a) treatment in +/+ cells; †P < .01 +/+ versus –/–MEFs by univariate linear regression models; n = 3 experiments.

The transcription factor STAT1 is indispensable for the majority of responses to both types of IFNs.32,40 To find out whether STAT1 was involved in the IFN-mediated Ttp expression we employed immortalized STAT1–/– MEFs and STAT1–/– MEFs reconstituted with STAT1 cDNA (STAT1+/+).30 The enhancing effect of IFN-γ (Figure 1C) or IFN-β (Figure 1D) on p38-stimulated Ttp expression was abolished in STAT1–/– cells.

These data demonstrate that IFNs strongly induce Ttp expression if a p38 MAPK stimulus is provided simultaneously.

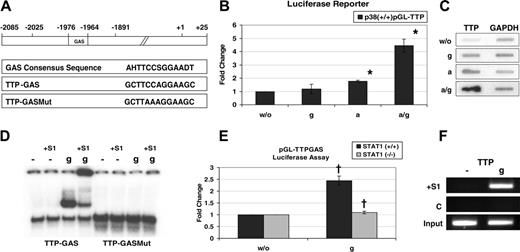

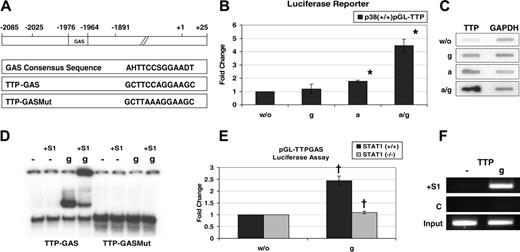

Ttp promoter contains a functional GAS element that binds STAT1

Ttp contains within the 3′ UTR an ARE that regulates the mRNA stability.25,26 The low induction of Ttp mRNA levels by IFNs alone (without the p38 MAPK stimulus) could be explained by constitutive decay of Ttp mRNA due to the ARE. The destabilizing activity of AREs is known to be released by activation of p38 MAPK.18,41 Thus, the requirement of p38 MAPK in IFN-induced Ttp expression might reflect the need to stabilize the newly synthesized mRNA by p38 rather than a p38-derived input in the transcription machinery. To address this issue, we cloned a 2-kb fragment of the Ttp promoter into the pGL2basic vector to obtain the plasmid pGL-TTP. The cloned fragment spans the region from base pair –2025 to +25 and contains a GAS element (ie, STAT1 binding site) as described in Figure 2A. The plasmid pGL-TTP together with the pEF-Zeo vector plasmid (to allow for selection with zeocin)30 were cotransfected into p38α+/+ cells and a bulk culture was established. These cells were assayed using qRT-PCR for induction of luciferase mRNA by IFN-γ, anisomycin, or both (Figure 2B). The experiment revealed that both IFN-γ and p38 MAPK are needed to induce transcription of the reporter gene. Since the reporter gene does not contain ARE sequences we conclude that IFN-γ requires the activity of p38 MAPK for stimulating Ttp transcription rather than for inhibiting ARE-mediated decay of Ttp mRNA. To substantiate this finding and because of the lower induction of the reporter construct compared with endogenous Ttp we conducted nuclear run-on assays. Nuclear run-ons assess transcription by measuring density of engaged RNA polymerases on specific promoters.37 They provide a direct measure of transcriptional activity by eliminating any posttranscriptional effects. The nuclear run-on revealed that treatment with both anisomycin and IFN-γ strongly enhanced the transcriptional activity on the Ttp promoter, confirming the role of both stimuli in Ttp transcription (Figure 2C).

Ttp promoter contains a functional GAS element that binds STAT1. (A) Schematic representation of the Ttp promoter as cloned into the reporter construct pGL2-TTP, comprising the region from –2025 to +25. The Ttp promoter contains a GAS element at the position –1976 to –1964. The reporter plasmid pGL2-TTP-GAS contains the TTP-GAS with flanking sequences (–2085 to –1891). The consensus for STAT1-binding GAS42 is shown (according to IUPAC nomenclature, H stands for A, C, or T; S stands for G or C; D stands for G, A, or T). Mutated TTP-GAS (TTP-GASMut) was obtained by introducing 2 point mutations. (B) p38α+/+ cells stably transfected with a reporter plasmid containing the luciferase gene under the control of a 2-kb fragment of the Ttp promoter (pGL2-TTP) were left untreated (w/o) or treated for 1 hour with IFN-γ(g), anisomycin (a), or both (a/g). Total RNA was isolated and luciferase expression was assayed by qRT-PCR. Error bars indicate SD. *P < .01 (a/g) versus (a) treatment by univariate linear regression models; n = 3 experiments. (C) For nuclear run-on assay p38α+/+ cells were left untreated (w/o) or treated for 25 minutes with IFN-γ (g), anisomycin (a), or both (a/g), nuclei were prepared and run-on reaction was performed. Nuclear RNA was isolated and hybridized to membranes containing cDNA of Gapdh (as a control) and Ttp. (D) Bac 1.2F5 mouse macrophages were stimulated for 30 minutes with IFN-γ (g) or left untreated (–), and whole-cell extracts were assayed for binding to a radioactively labeled TTP-GAS probe using EMSA. The results demonstrate IFN-γ–inducible binding of STAT1 to TTP-GAS but not to mutated TTP-GAS (TTP-GASMut). The presence of STAT1 in the complexes was confirmed by super-shift using STAT1 antibodies (lanes marked with +S1). (E) A luciferase reporter containing TTP-GAS (pGL-TTPGAS) was transfected into STAT1–/–MEFs reconstituted with STAT1 cDNA (STAT1+/+) and for control into the parental STAT1–/– cells. After the transfection, cells were divided in 2 halves and 24 hours later treated for 6 hours with IFN-γ (g) or left untreated. Error bars indicate SD. †P < .01 +/+ versus –/–MEFs by univariate linear regression models; n = 3 experiments. (F) For ChIP, STAT1+/+ MEFs were treated for 30 minutes with IFN-γ (g) or left untreated (–). Recruitment of STAT1 to the TTP promoter was assayed using STAT1 antibodies (+S1). A control ChIP was performed using rabbit preimmune serum (C). Equal amount of material used in the ChIP experiments was confirmed by PCR-amplification of the input DNA (input).

Ttp promoter contains a functional GAS element that binds STAT1. (A) Schematic representation of the Ttp promoter as cloned into the reporter construct pGL2-TTP, comprising the region from –2025 to +25. The Ttp promoter contains a GAS element at the position –1976 to –1964. The reporter plasmid pGL2-TTP-GAS contains the TTP-GAS with flanking sequences (–2085 to –1891). The consensus for STAT1-binding GAS42 is shown (according to IUPAC nomenclature, H stands for A, C, or T; S stands for G or C; D stands for G, A, or T). Mutated TTP-GAS (TTP-GASMut) was obtained by introducing 2 point mutations. (B) p38α+/+ cells stably transfected with a reporter plasmid containing the luciferase gene under the control of a 2-kb fragment of the Ttp promoter (pGL2-TTP) were left untreated (w/o) or treated for 1 hour with IFN-γ(g), anisomycin (a), or both (a/g). Total RNA was isolated and luciferase expression was assayed by qRT-PCR. Error bars indicate SD. *P < .01 (a/g) versus (a) treatment by univariate linear regression models; n = 3 experiments. (C) For nuclear run-on assay p38α+/+ cells were left untreated (w/o) or treated for 25 minutes with IFN-γ (g), anisomycin (a), or both (a/g), nuclei were prepared and run-on reaction was performed. Nuclear RNA was isolated and hybridized to membranes containing cDNA of Gapdh (as a control) and Ttp. (D) Bac 1.2F5 mouse macrophages were stimulated for 30 minutes with IFN-γ (g) or left untreated (–), and whole-cell extracts were assayed for binding to a radioactively labeled TTP-GAS probe using EMSA. The results demonstrate IFN-γ–inducible binding of STAT1 to TTP-GAS but not to mutated TTP-GAS (TTP-GASMut). The presence of STAT1 in the complexes was confirmed by super-shift using STAT1 antibodies (lanes marked with +S1). (E) A luciferase reporter containing TTP-GAS (pGL-TTPGAS) was transfected into STAT1–/–MEFs reconstituted with STAT1 cDNA (STAT1+/+) and for control into the parental STAT1–/– cells. After the transfection, cells were divided in 2 halves and 24 hours later treated for 6 hours with IFN-γ (g) or left untreated. Error bars indicate SD. †P < .01 +/+ versus –/–MEFs by univariate linear regression models; n = 3 experiments. (F) For ChIP, STAT1+/+ MEFs were treated for 30 minutes with IFN-γ (g) or left untreated (–). Recruitment of STAT1 to the TTP promoter was assayed using STAT1 antibodies (+S1). A control ChIP was performed using rabbit preimmune serum (C). Equal amount of material used in the ChIP experiments was confirmed by PCR-amplification of the input DNA (input).

Activation of transcription by STAT1 is mediated by GAS elements, 13-bp-long stretches of DNA that recruit STAT1 dimers (Figure 2A).42 We have identified a potential GAS at the position –1976 to –1964 in the mouse Ttp promoter (Figure 2A). The TTP-GAS was investigated for its STAT1 binding activity using EMSA experiments with TTP-GAS and a mutated version (mutTTP-GAS) that contained 2 point mutations within the GAS core sequence (Figure 2A). We detected STAT1 binding to the TTP-GAS that was abolished by the point mutations (Figure 2D). The presence of STAT1 was confirmed by super-shift using a STAT1 antibody.

To investigate whether the TTP-GAS is a functional transcription-enhancing element, the TTP-GAS together with its flanking sequences (–2085 to –1891) was cloned into the pGLpromoter vector, and the resulting plasmid pGL-TTP-GAS was transfected into STAT1-WT cells and STAT1–/– cells. Luciferase was induced in IFN-γ–stimulated STAT1-WT cells but not in STAT1–/– cells (Figure 2E). The luciferase induction was reproducibly 2- to 3-fold, which is consistent with reported constructs containing one GAS element only.43 Thus, we identified a functional GAS within the promoter of the mouse Ttp gene. Inspection of the human Ttp gene uncovered the presence of a GAS at a similar position, implicating a conserved transcriptional regulation of both human and mouse Ttp.

To strengthen the evidence for STAT1 binding to the Ttp promoter, chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were performed. Chromatin was precipitated from IFN-γ–treated or untreated MEFs using a STAT1 antibody. DNA was recovered from the immunocomplexes and a fragment of the TTP promoter comprising the TTP-GAS was PCR amplified. The promoter fragment was amplified from the IFN-γ–treated sample, proving IFN-γ–inducible binding of STAT1 to the Ttp promoter (Figure 2F).

These data establish STAT1 to bind to the Ttp promoter, thereby facilitating transcription of the Ttp gene.

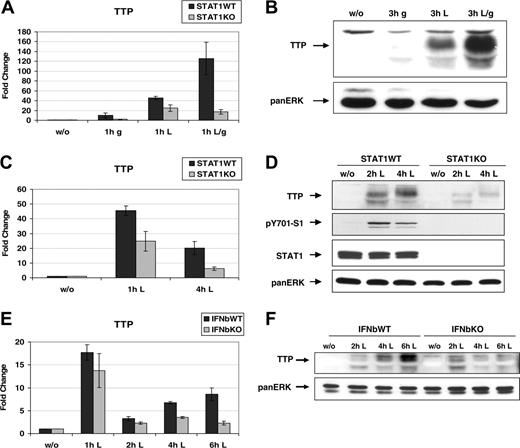

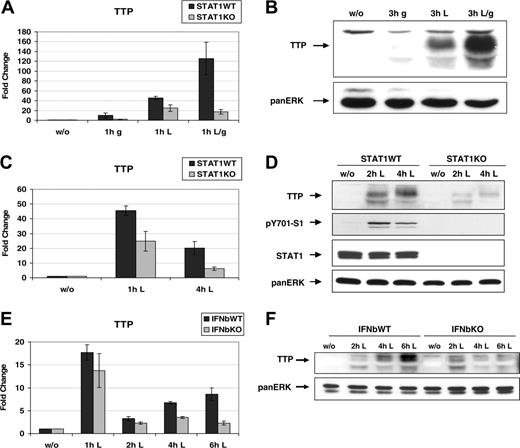

Maximal LPS-induced Ttp expression requires STAT1

To find out whether the increase of Ttp mRNA by the synergy of IFN and p38 MAPK pathways causes an equivalent rise in protein levels, Western blotting together with qRT-PCR analyses were performed. To activate p38 MAPK, LPS was applied instead of anisomycin since LPS is a physiological p38 agonist known to strongly induce TTP.20,21,27 Primary bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMMs) were stimulated for 1 hour (for qRT-PCR experiments; Figure 3A) or 3 hours (for Western blot analysis; Figure 3B) with IFN-γ, LPS, or both. The experiments revealed that IFN-γ caused only a weak increase of Ttp mRNA (Figure 3A) or TTP protein levels (Figure 3B). Stimulation of cells with LPS resulted in a significant induction of both mRNA and protein. However, a combined treatment of macrophages with LPS and IFN-γ caused a robust amplification of Ttp mRNA and protein that by far exceeded that induced by LPS alone. Thus, the induction of TTP protein by IFN-γ and/or LPS virtually mirrored the increase of Ttp mRNA that was mediated by the same stimuli. The qRT-PCR experiments were also performed in STAT1 knockout (KO) macrophages to confirm the STAT1 dependency (Figure 3A). Interestingly, LPS induced Ttp mRNA 50-fold in wild-type (WT) macrophages but only 25-fold in STAT1KO cells, indicating that STAT1 was also involved in LPS-induced Ttp expression. It is known that in macrophages LPS causes activation of MAPKs, NFκB, and IRF3, resulting in rapid production of a range of cytokines including IFN-β.44-47 IFN-β in turn activates STAT1 and STAT2, and consequently the expression of GAS- and ISRE-containing genes, resulting in maximal activation of macrophages. Hence, LPS causes activation of both p38 MAPK and IFN pathways, thereby providing a system to examine their influence on gene expression under physiologic conditions. We used this system to investigate the biological significance of the synergistic effects of IFNs and p38 MAPK on Ttp expression. BMMs isolated from WT and STAT1KO mice were treated with LPS for 1 hour and 4 hours (in case of qRT-PCR; Figure 3C), and for 2 hours and 4 hours (in case of Western blots; Figure 3D). The experiments demonstrated that both TTP mRNA and protein are rapidly and strongly induced in WT macrophages whereas the induction in STAT1KO macrophages is weak and does not reach, at any time point, the levels detected in WT cells. LPS treatment causes phosphorylation of TTP, resulting in the appearance of slower migrating bands.21 Activation of STAT1 by LPS-induced endogenous production of IFN-β was revealed using phosphoTyr701-STAT1 antibody. To confirm the role of IFN-β in the full induction of TTP by LPS, we examined Ttp expression in BMM from IFNβKO mice (Figure 3E-F). The data show that initially (at 1 hour), LPS induced similar Ttp mRNA (Figure 3E) and protein (Figure 3F) levels in both control and IFNβKO cells. However, in control cells Ttp mRNA levels remained detectable and protein levels continued to rise whereas in the IFNβKO cells Ttp mRNA dropped close to basal levels at the 6-hour time point, and protein expression was declining. The Ttp expression profile, which is initially dependent mostly on the p38 MAPK and in the second phase also on IFN, is consistent with the biphasic expression of Ttp observed in RAW macrophages.25 Our data proved that activation of STAT1 by the endogenous IFN-β is required for the maximal expression of Ttp in LPS-treated macrophages. The differences in Ttp expression between control and STAT1KO cells (Figure 3C-D) were more dramatic than those between control and IFNβKO (Figure 3E-F), indicating that other IFNs or STAT1-activating cytokines also play a role.

STAT1 is required for full expression of Ttp in LPS-treated primary macrophages. (A) Macrophages derived from bone marrow (BMM) of STAT1WT and STAT1KO mice were left untreated or treated with IFN-γ (g), LPS (L), or both (L/g) and Ttp mRNA induction was measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to samples from untreated cells. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3 experiments. (B) BMMs isolated from STATWT mice were treated as explained for panel A, except the time of the treatment was 3 hours instead of 1 hour. TTP protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting of whole-cell extracts using a TTP antibody. The blot was reprobed with a panERK antibody to control for equal protein loading. (C) BMMs from STAT1WT and STAT1KO mice were treated for 1 hour and 4 hours with LPS or left untreated, and mRNA induction was analyzed as described in panel A. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3 experiments. (D) Same cells as those used in panel C were treated for 2 and 4 hours with LPS or left untreated. TTP protein was detected by Western blotting of whole-cell extracts using a TTP antibody. Activation of IFN signaling by endogenous production of type I interferon in LPS-treated macrophages was demonstrated using antibody to tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 (pY701-S1). Equal protein loading was confirmed using a STAT1 antibody and a panERK antibody. (E) BMMs from IFN-β knockout (IFNbKO) and wild-type controls (IFNbWT) were stimulated with LPS for the times indicated. Total RNA was isolated and qRT PCR was performed. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3 experiments. (F) Whole-cell extracts of the same cells as used in panel E were stimulated with LPS as indicated. TTP protein was detected by Western blotting using a TTP antibody.

STAT1 is required for full expression of Ttp in LPS-treated primary macrophages. (A) Macrophages derived from bone marrow (BMM) of STAT1WT and STAT1KO mice were left untreated or treated with IFN-γ (g), LPS (L), or both (L/g) and Ttp mRNA induction was measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to samples from untreated cells. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3 experiments. (B) BMMs isolated from STATWT mice were treated as explained for panel A, except the time of the treatment was 3 hours instead of 1 hour. TTP protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting of whole-cell extracts using a TTP antibody. The blot was reprobed with a panERK antibody to control for equal protein loading. (C) BMMs from STAT1WT and STAT1KO mice were treated for 1 hour and 4 hours with LPS or left untreated, and mRNA induction was analyzed as described in panel A. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3 experiments. (D) Same cells as those used in panel C were treated for 2 and 4 hours with LPS or left untreated. TTP protein was detected by Western blotting of whole-cell extracts using a TTP antibody. Activation of IFN signaling by endogenous production of type I interferon in LPS-treated macrophages was demonstrated using antibody to tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 (pY701-S1). Equal protein loading was confirmed using a STAT1 antibody and a panERK antibody. (E) BMMs from IFN-β knockout (IFNbKO) and wild-type controls (IFNbWT) were stimulated with LPS for the times indicated. Total RNA was isolated and qRT PCR was performed. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3 experiments. (F) Whole-cell extracts of the same cells as used in panel E were stimulated with LPS as indicated. TTP protein was detected by Western blotting using a TTP antibody.

We conclude that Ttp mRNA and protein are induced by synergistic function of p38 MAPK and STAT1, and IFN/STAT1 signaling is required for full induction of Ttp expression by LPS.

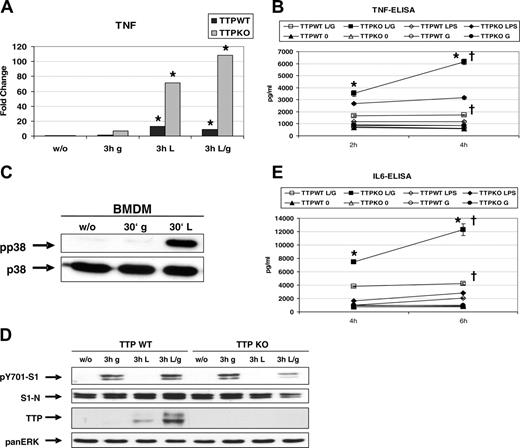

IFN-stimulated Ttp expression limits induction of TNFα and IL-6 in activated macrophages

We asked whether the increased Ttp expression in macrophages treated with both IFNs and LPS compared with single treatments alone might affect the expression of TNFα, a known TTP target. BMMs from TTPKO and littermate TTPWT mice were treated with LPS, IFN-γ, or both, and the TNFα mRNA and protein levels were monitored (Figure 4A-B). IFN-γ did not induce TNFα mRNA in TTPWT cells, whereas it caused a weak but consistent 6- to 8-fold induction in TTPKO cells, indicating that IFN-γ can activate TNFα expression in the absence of TTP. LPS-induced TNFα mRNA levels were approximately 3-fold higher in TTPKO cells than in TTPWT cells, thus in agreement with published data on TTP-mediated destabilization of TNFα transcripts.19,48 Importantly, TNFα mRNA was even more induced in TTPKO macrophages treated with both IFN-γ and LPS, whereas it slightly decreased in double-treated TTPWT macrophages (Figure 4A). This effect resulted in 10-fold higher TNFα mRNA levels in double-treated TTPKO cells compared with TTPWT cells. Quantification of secreted TNFα revealed that during the treatment (2-4 hours) with both IFN-γ and LPS, the TNFα levels increased by 80% in supernatants of TTPKO but only by 5% in the supernatants of TTPWT macrophages (Figure 4B). This continuous production caused 3-fold higher TNFα levels after 4 hours in supernatants of TTPKO compared with control cells. Importantly, although LPS caused higher production of TNFα in TTPKO cells compared with TTPWT cells, the total TNFα levels remained below those of doubletreated cells and the increase over time remained low (15% in TTPKO versus no increase in TTPWT cells). IFN-γ alone did not induce TNFα secretion in either cell type, although it caused a modest increase of TNFα mRNA in TTPKO cells. This result is consistent with the inability of IFN-γ to activate p38 MAPK, which is required for translation of TNFα mRNA and secretion of the cytokine.17 The lack of p38 MAPK activation by IFN-γ alone is shown in Figure 4C. To rule out that an increased IFN signaling in TTPKO cells was responsible for the higher IFN-γ–dependent TNFα expression in TTPKO macrophages, we analyzed the activation of STAT1. Figure 4D demonstrates that activation of STAT1 by IFN-γ was not augmented in TTPKO cells. In fact, we observed an approximately 2-fold lower STAT1 activation at very early time points (data not shown).

Interferon-stimulated Ttp expression limits induction of TNFα and IL-6. (A) BMMs derived from Ttp wild-type (TTPWT) and deficient (TTPKO) mice were left untreated or treated with IFN-γ (g), LPS (L), or both (L/g) for 3 hours and TNFα mRNA induction was determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to untreated samples. * P < .05 treated versus untreated cells by univariate linear regression models. (B) BMMs from TTPWT and TTPKO were stimulated for the times indicated with IFN-γ (G), LPS, or both (L/G), or left untreated (0). Supernatants were collected and analyzed for TNFα cytokine by ELISA. *P < .01, 4 hours versus 2 hours in L/G-treated KO cells; †P < .01, KO versus WT BMMs by univariate linear regression models, n = 3 experiments.(C) TTPWT BMMs were treated for 30 minutes (30′) with IFN-γ and LPS, and activation of p38 was demonstrated using an antibody against phosphorylated p38 MAPK (pp38). Equal protein loading was confirmed using a p38 antibody. (D) BMMs from TTPWT and TTPKO mice were treated as described in panel A. Absence of TTP protein in TTPKO cells was confirmed by Western blotting of whole-cell extracts using a TTP antibody. Activation of IFN signaling by endogenous production of type I interferon in LPS-treated macrophages was demonstrated using an antibody to tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 (pY701-S1). Equal protein loading was confirmed using a STAT1 antibody and a panERK antibody. (E) BMMs from TTPWT and TTPKO were stimulated for the times indicated with IFN-β (B), LPS, or both (L/B) or left untreated(0). Supernatants were collected and IL-6 was measured by ELISA. *P < .01, 6 hours versus 4 hours in L/B-treated KO cells; †P < .01, KO versus WT BMMs by univariate linear regression models, n = 3 experiments.

Interferon-stimulated Ttp expression limits induction of TNFα and IL-6. (A) BMMs derived from Ttp wild-type (TTPWT) and deficient (TTPKO) mice were left untreated or treated with IFN-γ (g), LPS (L), or both (L/g) for 3 hours and TNFα mRNA induction was determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to untreated samples. * P < .05 treated versus untreated cells by univariate linear regression models. (B) BMMs from TTPWT and TTPKO were stimulated for the times indicated with IFN-γ (G), LPS, or both (L/G), or left untreated (0). Supernatants were collected and analyzed for TNFα cytokine by ELISA. *P < .01, 4 hours versus 2 hours in L/G-treated KO cells; †P < .01, KO versus WT BMMs by univariate linear regression models, n = 3 experiments.(C) TTPWT BMMs were treated for 30 minutes (30′) with IFN-γ and LPS, and activation of p38 was demonstrated using an antibody against phosphorylated p38 MAPK (pp38). Equal protein loading was confirmed using a p38 antibody. (D) BMMs from TTPWT and TTPKO mice were treated as described in panel A. Absence of TTP protein in TTPKO cells was confirmed by Western blotting of whole-cell extracts using a TTP antibody. Activation of IFN signaling by endogenous production of type I interferon in LPS-treated macrophages was demonstrated using an antibody to tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 (pY701-S1). Equal protein loading was confirmed using a STAT1 antibody and a panERK antibody. (E) BMMs from TTPWT and TTPKO were stimulated for the times indicated with IFN-β (B), LPS, or both (L/B) or left untreated(0). Supernatants were collected and IL-6 was measured by ELISA. *P < .01, 6 hours versus 4 hours in L/B-treated KO cells; †P < .01, KO versus WT BMMs by univariate linear regression models, n = 3 experiments.

One of the other major cytokines produced by activated macrophages is IL-6. To investigate whether TTP plays a similar role in IL-6 expression as in TNFα expression, we performed ELISA to detect secreted IL-6 in TTPKO and control BMMs stimulated with IFN-β, LPS, or both (Figure 4E). Similar to TNFα, the production of IL-6 was strongly enhanced by double treatment (LPS and IFN-β) in TTPKO cells and raised by 60% between 4 hours and 6 hours of treatment, whereas in TTPWT cells IL-6 was 2-fold lower after 4 hours and increased only by 5% after 6 hours. Importantly, IFN-β alone did not induce IL-6 in either cell type, and LPS caused only a weak IL-6 expression that was 20% higher in TTPKO cells.

These results demonstrate that IFNs have the potential to strongly augment LPS-induced TNFα and IL-6 expression, and this effect is counter-balanced by the simultaneous induction of TTP.

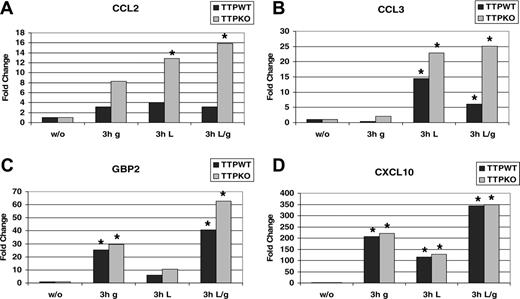

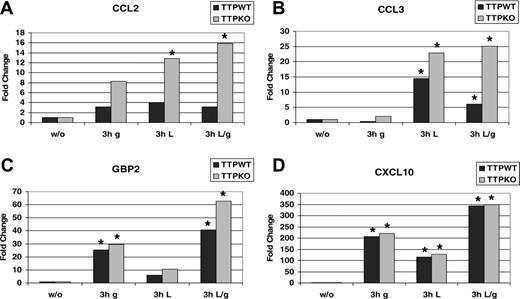

IFNs exhibit a TTP-dependent suppressive effect on expression of Ccl2 and Ccl3

We reasoned that the IFN-induced TTP protein might act on other proinflammatory molecules such as chemokines. According to the ARE database, human Ccl3 contains AREs in its 3′ UTRs.49 Similar sequences are found in the mouse chemokine genes Ccl2 (MCP1) and Ccl3 (MIP-1α). We performed qRT-PCR analysis of the Ccl2 and Ccl3 mRNA isolated from TTPKO and littermate TTPWT BMMs treated with IFN-γ, LPS, or both. Figure 5A shows that Ccl2 mRNA was induced 3- to 4-fold in TTPWT cells treated with either stimulus. In TTPKO cells the induction was 8-fold by IFN-γ, 12-fold by LPS, and augmented to 16-fold by the double treatment. These data suggest that Ccl2 is a TTP target and that the synergistic induction of Ccl2 by LPS and IFN-γ is suppressed by the simultaneous synergistic induction of TTP. Similar analysis of Ccl3 expression revealed that in TTPWT cells Ccl3 mRNA levels were 60% lower upon combined LPS and IFN-γ treatment as compared with LPS alone (Figure 5B). In contrast, in TTPKO cells treated with both LPS and IFN-γ slightly increased Ccl3 mRNA if compared with LPS treatment alone. The expression of the Gbp2 or Cxcl10 genes, which are both stimulated by IFN-γ and do not contain an obvious ARE in their 3′ UTRs, was not (in the case of Cxcl10) or only modestly (in the case of Gbp2) affected by the TTP deficiency (Figure 5C-D). Thus, IFN-induced TTP can specifically reduce expression of a subset of inflammation-related genes that contain AREs in their mRNAs.

Discussion

This work emphasizes the role of IFNs in the negative control of inflammatory responses. The negative control mechanism is based on the ability of IFNs to induce the expression of Ttp, a key mediator of the decay of several inflammatory mRNAs that contain AU-rich elements in their 3′ UTRs.

Interferon- and LPS-induced Ttp expression has a suppressive effect on Ccl2 and Ccl3 mRNA production. BMMs derived from TTP wild-type (TTPWT) and deficient (TTPKO) mice were left untreated or treated with IFN-γ(g), LPS (L), or both (L/g) for 3 hours. Total RNA was extracted and the induction of Ccl2 (A), Ccl3 (B), Gbp2 (C), and Cxcl10 (D) genes was detected by real-time RT-PCR using Taqman assays from Applied Biosystems. To obtain mRNA induction, qRT-PCR values were normalized to those of untreated cells. *P < .05, treated versus untreated cells by univariate linear regression models.

Interferon- and LPS-induced Ttp expression has a suppressive effect on Ccl2 and Ccl3 mRNA production. BMMs derived from TTP wild-type (TTPWT) and deficient (TTPKO) mice were left untreated or treated with IFN-γ(g), LPS (L), or both (L/g) for 3 hours. Total RNA was extracted and the induction of Ccl2 (A), Ccl3 (B), Gbp2 (C), and Cxcl10 (D) genes was detected by real-time RT-PCR using Taqman assays from Applied Biosystems. To obtain mRNA induction, qRT-PCR values were normalized to those of untreated cells. *P < .05, treated versus untreated cells by univariate linear regression models.

Both IFN and p38 MAPK pathways are stimulated in macrophages upon challenge with microbes or microbial products. These signaling cascades cause, either individually or in synergy with each other, vast changes in gene expression. The reprogramming of gene expression is essential for activation of immune responses but also for balancing them. For the maintenance of immune homeostasis both signaling pathways elicit various negative regulatory mechanisms. The most prominent inhibitory molecules induced by IFNs are SOCS1 and SOCS3.50 Feedback inhibition caused by p38 MAPK is brought about by transcriptional induction of diverse phosphatases acting either directly on p38 MAPK or on upstream activating enzymes such as MKK3.51 In addition, p38 MAPK plays a key role in anti-inflammatory responses by increasing levels of TTP that possesses strong anti-inflammatory properties and destabilizes the mRNA of the most potent immunostimulating cytokine, TNFα.19-21,25,26 p38 MAPK also negatively interferes with responses to IFNs by stimulating the expression of SOCS1.50 On the other hand, there is only a limited evidence for IFNs playing a role in suppressing the proinflammatory function of p38 MAPK that is elicited mainly by induction of TNFα. In this work, we show for the first time that IFNs and the IFN-activated transcription factor STAT1 play a fundamental role in expression of Ttp, an important factor in negative regulation of cytokine expression. We demonstrate that for the full induction of TTP by LPS the autocrine, IFN-β–mediated activation of STAT1 is required. These data suggest that IFNs can augment the feedback inhibition exerted by TTP on cytokine (eg, TNFα) production. We confirmed this hypothesis by employing bone marrow–derived macrophages from TTPKO mice. The expression of TNFα, IL-6, Ccl2, and Ccl3 was augmented in TTPKO cells treated with both LPS and IFNs, as compared with single treatments alone. In contrast, the expression of these genes in wild-type cells was only moderately increased or even reduced by the combined treatment as compared with single treatments. Thus, the strong proinflammatory activity of IFNs is limited by their ability to induce expression of Ttp. Since Ttp has to be transcribed, translated, and posttranscriptionally modified before engagement in the regulatory loop, it is likely that the Ttp-mediated negative feedback becomes apparent at later phases of inflammatory responses. In this scenario, IFN and LPS first act synergistically on activation of proinflammatory molecules that are, however, down-regulated by the synergistic increase of TTP levels later on. We have employed IFN-β–deficient cells to prove the role of the autocrine production of IFN-β in LPS-mediated induction of Ttp. Interestingly, the Ttp expression was more efficiently affected by the lesion in STAT1 than in the IFN-β gene. Since mouse macrophages do not produce IFN-γ in response to LPS,52 the members of the IFN-α gene family2,53 might be responsible for the lower reduction of Ttp expression in the IFN-β–deficient cells. However, in macrophages the IFN-α production has been reported to depend entirely on IFN-β synthesis.54 Thus, the more likely STAT1 agonists in IFN-β knockout cells are cytokines, such as IL-6, that are released from LPS-treated macrophages and known to activate (albeit weakly) STAT1.

In this study we have characterized a GAS element within the Ttp promoter that is conserved in mice and men. The TTP-GAS binds STAT1, yet STAT1 needs, in addition to IFNs, a p38-derived stimulus to activate Ttp transcription. This finding is consistent with reports on the role of p38 MAPK in promoting STAT1-driven transcription.10,11 While the molecular mechanism of the synergy is currently not known, our findings indicate that the number of IFN-stimulated genes (currently more than 30055 ), will grow considerably if the IFN stimulus is supported by a p38 MAPK agonist.

In conclusion, we establish IFNs and the IFN-activated transcription factor STAT1 to play an important role in the transcription of Ttp, a major ARE-directed TNFα mRNA destabilizing factor. The IFN signal must be accompanied by a p38 MAPK stimulus for STAT1 to become transcriptionally active at the Ttp promoter. Under physiological conditions, both signaling pathways (IFN and p38 MAPK) are activated when macrophages encounter bacteria or bacteria-derived products such as LPS. Consistently, STAT1 is required for complete induction of Ttp in LPS-treated macrophages. The IFN-dependent Ttp induction exerts a negative effect on the expression of several ARE-containing proinflammatory molecules, thereby limiting potentially harmful consequences of uncontrolled cytokine or chemokine production. These findings reveal a previously unrecognized immunomodulatory mechanism by which IFNs contribute to immune system homeostasis.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 2, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3058.

Supported by the Austrian Research Foundation (FWF) and the European Science Foundation (ESF) through grants P16 726-B14 and I27-B03 (P.K.) and FWF grant SFB F28 (P.K., M.M.); the Viennese Foundation for Science, Research, and Technology (WWTF; project LS133; M.M.); and the Austrian Ministry of Education and Science (BMBWK; project BM:BWK OEZBT GZ200.074/I-VI/Ia/2002; M.M.).

I.S. designed and performed research and analyzed data; P.K. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; B.S. and I.G. performed research and analyzed data; C.V. analyzed data; and T.K., M.M., and P.J.B. contributed new reagents.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We wish to thank Andy Clark for kindly providing us with TTP antibodies, and Matthias Gaestel and Alexey Kotlyarov for sharing TTP mice. Birgit Strobl, Silvia Stockinger, and Heather Zwaferink are gratefully acknowledged for critically reading the manuscript.