Abstract

The β-globin locus control region (LCR) is a large DNA element that is required for high-level expression of β-like globin genes from the endogenous mouse locus or in transgenic mice carrying the human β-globin locus. The LCR encompasses 6 DNaseI hypersensitive sites (HSs) that bind transcription factors. These HSs each contain a core of a few hundred base pairs (bp) that has most of the functional activity and exhibits high interspecies sequence homology. Adjoining the cores are 500- to 1000-bp “flanks” with weaker functional activity and lower interspecies homology. Studies of human β-globin transgenes and of the endogenous murine locus show that deletion of an entire HS (core plus flanks) moderately suppresses expression. However, human transgenes in which only individual HS core regions were deleted showed drastic loss of expression accompanied by changes in chromatin structure. To address these disparate results, we have deleted the core region of 5′HS2 from the endogenous murine β-LCR. The phenotype was similar to that of the larger 5′HS2 deletion, with no apparent disruption of chromatin structure. These results demonstrate that the greater severity of HS core deletions in comparison to full HS deletions is not a general property of the β-LCR. (Blood. 2006;107:821-826)

Introduction

Locus control regions (LCRs) are specialized tissue-specific DNA regulatory elements that are functionally defined by their ability to improve position independence and copy number dependence of linked genes in transgenic mice. The β-globin LCR was the first identified and has been the most heavily studied. Other LCRs have been identified that are postulated to be important in regulating genes at their endogenous locations.1-3 However, it is unclear whether regulatory activities demonstrated in transgenic studies are relevant for LCRs in their endogenous loci.

The human and mouse β-globin loci are highly homologous. Both have a series of β-like globin genes that are activated in erythroid cells at different developmental stages (reviewed in Stamatoyannopoulos et al4 ). The human β-globin LCR is a group of hypersensitive sites (HSs) located 6 to 22 kb upstream of the embryonic ϵ-globin gene.5,6 The murine β-globin LCR is very similar to the human β-globin LCR in its structure, sequence, and activity7 (Figure 1). The human LCR has been studied predominantly as transgenes in mice or cells, whereas the murine LCR has been predominantly studied by targeted mutation in its endogenous location. Deletion of the murine β-globin LCR showed that it is required for high-level expression of all the linked β-like globin genes, but developmental timing of gene expression and the chromatin structure of the remaining locus was unaffected by the LCR deletion.8,9

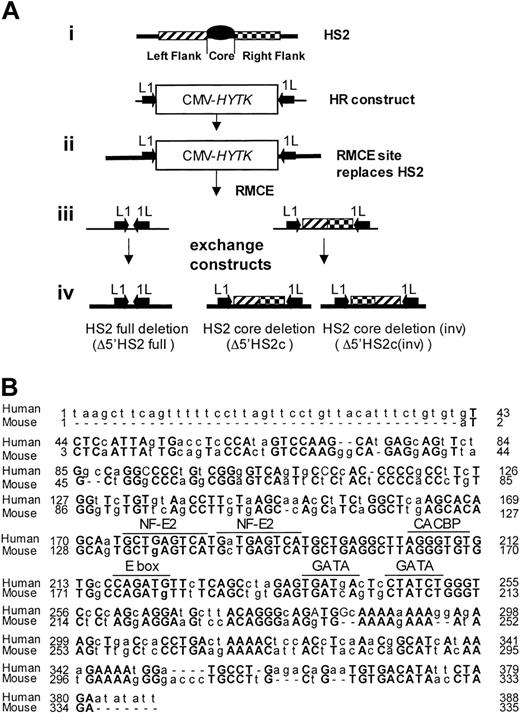

Each HS contains a very highly conserved core fragment that is 200- to 400-bp long and less conserved but recognizably homologous sequences of roughly 500 to 1000 bp flanking the core (Figure 1B). The cores from the major HS contain transcription factor binding sites that are generally similar between HSs. In transfection assays and transgenic animal studies, the core fragment demonstrated most of the transcriptional activation activity of the corresponding HS.10-12 Based on those findings it was proposed that the cores encode most of the functional activities of the LCR. The flanking sequences do form minor DNaseI HSs and carry limited transcriptional activation activities.13

Two models can be delineated for how the multiple LCR HSs interact to regulate gene expression. An additive model proposes that each 5′ HS contributes independently in an additive manner to LCR activity. This model is supported by deletion studies of individual HSs at the mouse locus.14-16 Deletion of individual HSs from the endogenous mouse locus lead to a 0% to 40% reduction in gene expression. If the suppressive activities of the individual site deletions are added together it equals the 95% reduction of gene expression seen with deletion of the entire LCR.8,9 When 2 individual sites are deleted the suppression roughly equals the sum of the suppression seen when each is individually deleted (M.A.B., R. Byron, T. Ragoczy, A. Telling, and M.G., manuscript in preparation). Supporting the idea that the HSs do not interact structurally is the finding that deletions of individual HSs do not affect formation of the remaining HSs.17

A synergistic model proposes that the HSs interact structurally and functionally and the absence of individual HSs will severely impact the LCR. The LCR was proposed to form a single structural entity, a holocomplex.18 If the LCR forms a holocomplex then it follows that disruption of some portion of the structure could lead to disruption of the entire structure. This model is supported by transfection studies of constructs with different HS combinations13,19,20 and by deletion studies of human LCR HS core regions in human β-globin yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) transgenic mice.18,21-23 In YAC transgenic mice, deletion of individual human HS cores (HS2, HS3, or HS4) results in severe reduction of all β-like globin gene expression and failure to form the remaining HSs,21,24,25 suggesting that LCR HSs are mutually interdependent for their formation. Findings that complicate a simple interpretation of these studies are that larger deletions of these same human 5′ HSs, including the core plus the flanking sequences, result in a more moderate reduction of β-like globin gene expression26 comparable to that of full site deletions within the mouse locus.

Generating HS2 core deletion. (A) Strategies for the murine β-globin LCR 5′HS2 deletions. (i) Schematic representation of HS2 and the homologous recombination (HR)-targeting construct with the CMV-HyTK gene flanked by 2 inverted loxP sites (arrows) replacing the 5′HS2 full site. (ii) Structure of the HR product with the RMCE site replacing the full 5′HS2. (iii) RMCE constructs. (iv) RMCE products showing the full deletion and the core deletion with the 5′HS2 flanks in their normal or inverted orientation. (B) Sequence comparison of the human and mouse 5′HS2 core deletions, including the binding sites of transcription factors most likely to be bound to the core.7

Generating HS2 core deletion. (A) Strategies for the murine β-globin LCR 5′HS2 deletions. (i) Schematic representation of HS2 and the homologous recombination (HR)-targeting construct with the CMV-HyTK gene flanked by 2 inverted loxP sites (arrows) replacing the 5′HS2 full site. (ii) Structure of the HR product with the RMCE site replacing the full 5′HS2. (iii) RMCE constructs. (iv) RMCE products showing the full deletion and the core deletion with the 5′HS2 flanks in their normal or inverted orientation. (B) Sequence comparison of the human and mouse 5′HS2 core deletions, including the binding sites of transcription factors most likely to be bound to the core.7

Identification of HS2 core, HS2 core inverted, and HS2 full deletion clones. (A) Map shows the Southern strategies to screen the modified ES clones. N indicates cutting sites for NheI; the short line under the maps, the probe; and ▨, the CMV-HyTK gene after homologous recombination. The expected band sizes are noted. (B) ΔHS2 full deletion Southern blot. Lanes 1 and 5, ΔHS2 full/S; lane 2, D/S; and lanes 3 and 4, HS2(HR)/S. (C) ΔHS2 core deletion Southern blot. Lanes 1 and 3, ΔHS2c/S; lane 2, ΔHS2c(inv)/S; lane 4, HS2(HR)/S; and lane 5, D/S.

Identification of HS2 core, HS2 core inverted, and HS2 full deletion clones. (A) Map shows the Southern strategies to screen the modified ES clones. N indicates cutting sites for NheI; the short line under the maps, the probe; and ▨, the CMV-HyTK gene after homologous recombination. The expected band sizes are noted. (B) ΔHS2 full deletion Southern blot. Lanes 1 and 5, ΔHS2 full/S; lane 2, D/S; and lanes 3 and 4, HS2(HR)/S. (C) ΔHS2 core deletion Southern blot. Lanes 1 and 3, ΔHS2c/S; lane 2, ΔHS2c(inv)/S; lane 4, HS2(HR)/S; and lane 5, D/S.

To explain why deletion of the cores of HSs in human locus transgenes is so disruptive to normal expression and chromatin structure, it was proposed that individual HS core fragments interact synergistically with each other to form a single “active site” within the LCR holocomplex and deletion of any core fragment will destroy the formation of the active site and the transactivation activity of the LCR holocomplex.21 To explain why deletion of the full HS did not cause as severe a reduction in expression, it has been proposed that deletion of the entire HS including core and flanks permits a new type of holocomplex to form with a new active site that can support partial or full expression.21 If the proposed model is correct, it would likely be a fundamental aspect of LCR function. To test this model, we have deleted the core of 5′HS2 and the full 5′HS2 from the mouse locus and determined the influence of this deletion on gene expression and HS formation.

Materials and methods

Generation of the β-globin LCR 5′HS2-targeted ES clones

A 1194-bp KpnI fragment (-10 415 to -9221 relative to the start site of Ey [Hbb-y]) of the mouse 5′HS2 site was first replaced by the CMV-HyTK (fusion of hygromycin resistance and HSV thymidine kinase) gene through homologous recombination. The homologous recombination (HR) construct makes the same deletion as the previously reported full 5′HS2 deletion.14 The selectable marker used is CMV-HyTK, which is flanked by inverted LoxP sites (floxed) to facilitate further modification of the site by recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE).27 Embryonic stem (ES) cells used for the study were DS2B ES cells that are predominantly derived from 129SV ES cells but are heterozygous at the β-globin locus for diffuse (Hbb(d)) and single (Hbb(s)) alleles. ES clones with targeting of 5′HS2 on the diffuse allele were used for further experiments.

RMCE to generate the β-globin LCR HS2 core deletion ES clones (ΔHS2full and ΔHS2core)

Principles of the RMCE method have been described previously.27 The procedures were modified to achieve RMCE in ES cells. In short, 2 × 106 HS2 HR-targeted ES cells were resuspended in PBS, and 125 μg exchanging plasmid and 25 μg CMV-Cre plasmid were added to the HR-targeted ES cells. The ES cells and the plasmids were subjected to electroporation. Cells were cultured and selected with 3 μM ganciclovir in the absence of feeder cells. Ganciclovir-resistant ES clones were picked and genomic DNA was purified for Southern screening to identify correct RMCE clones and to determine the orientation of the flanking sequences.

To generate ES clones with the 5′HS2 core deletion, the exchanging plasmid contains the 5′HS2 flanking sequences flanked by inverted LoxP sites (Figure 2), which results in a 338-bp (-9838 bp to -9500 bp relative to the Ey start site) deletion of the 5′HS2 core after successful RMCE. This 338-bp deletion is slightly smaller than the deletion made in the human HS2 core21 and was designed to delete the region of high homology between the cores. The deletion removes all consensus binding sites in the core.7 To generate ES clones with the 5′HS2 full deletion, the exchanging plasmid contains a short polylinker sequence that is floxed by inverted LoxP sites. The ganciclovir-resistant ES clones were further analyzed by Southern blot to identify the exchanged ES clones and to determine the orientation of the flanking sequence.

β-Like globin gene expression after in vitro erythroid differentiation of 5′HS2 mutant ES clones. Sample gels are shown. S indicates the single allele, and D, the diffuse allele on which mutations are made; ΔHS2c, the core deletion; and ΔHS2full, the full site deletion. Wild-type (WT) values are the WT D/S ratio normalized to 1.0. The mutant/S ratio is divided by WT D/S ratio before normalization of WT D/S. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean for 10 individual primitive (Bh1 assay) or definitive (Bmajor and Bminor assay) erythroid colonies before normalization.

β-Like globin gene expression after in vitro erythroid differentiation of 5′HS2 mutant ES clones. Sample gels are shown. S indicates the single allele, and D, the diffuse allele on which mutations are made; ΔHS2c, the core deletion; and ΔHS2full, the full site deletion. Wild-type (WT) values are the WT D/S ratio normalized to 1.0. The mutant/S ratio is divided by WT D/S ratio before normalization of WT D/S. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean for 10 individual primitive (Bh1 assay) or definitive (Bmajor and Bminor assay) erythroid colonies before normalization.

Generation of the β-globin LCR HS2core deletion mouse (ΔHS2core)

ES clones with the HS2 core deletion and with the endogenous flanking sequences in their normal orientation were used to produce a mouse line by standard techniques.14 Germ line-transmitting mice were bred to 129svJ to generate ΔHS2core/diffuse (D) male mice to be bred to C57bl6 female mice and thereby generate mutant (mut)/single (S) and wild-type (WT)/S mice for β-globin gene-expression analysis.

In vitro hematopoietic differentiation of ES cells

The ES-cell erythroid differentiation assay is based on previously published procedures with modifications.28 Wild-type and mutant DS 2B ES cells were first differentiated into embryonic bodies (EBs) in primary ES differentiation medium containing 1% methylcellulose (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) in IMDM supplemented with 15% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1.5 × 10-4 M MTG, 40 ng/mL mouse stem-cell factor (mSCF). For Ey and Bh1 (Hbb-bh1) gene expression, day-4 EBs were harvested and replated into secondary differentiation medium containing 1% methylcellulose in IMDM supplemented with 5% protein-free hybridoma medium (PFHMII; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), 5% plasma-derived serum (PDS), 150 ng/mL SCF, 30 ng/mL IL-3, 30 ng/mL IL-6, and 2 U/mL erythropoietin. For Bmajor (Hbb-b1) and Bminor (Hbb-b2) expression, day-6 or later EBs were harvested and used for secondary plating in the same differentiation medium. Single erythroid colonies were picked to make RNA for gene-expression assay.

RNA preparation

Total RNA was extracted with RNAbee (Tel-test, Friendswood, TX) following the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA from day 10.5 (d10.5) embryonic yolk sac was used to analyze the expression of β-like globin genes in primitive erythroid cells. Total RNA from d14.5 fetal liver and adult peripheral blood was used to analyze the expression of β-like globin genes in definitive erythroid cells. For gene expression in single colonies picked from the secondary ES-cell differentiation, the colonies were lysed in 10 μL cell-lysis buffer containing 0.5% NP-40 in 50 mM Tris.Cl and 10U RNase inhibitor, then the cell lysate was centrifuged at 9000g for 5 minutes. Total RNA was collected from the supernatant.

RT-PCR analysis of globin gene expression

Total RNA (200-400 ng) was used for reverse transcriptase (RT) reactions with random hexamer primers. D/S RT-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays were done and analyzed as described previously,14 with the exception that the radioactive nucleotide was added prior to the final PCR cycle to avoid problems with heteroduplex formation.

Mapping DNaseI HSs at the β-globin LCR

Phenylhydrazine mouse treatment and DNaseI β-globin LCR HS analysis have been described previously.29 DNA was extracted from DNaseI-treated splenocyte nuclei from phenylhydrazine-treated wild-type D/D or ΔHS2core/ΔHS2core mice and digested with HpaI. The formation of HSs was detected by Southern blot using a probe from -2867 to -3469 relative to the Ey mRNA cap site.

Results

Generating 5′HS2 mutant ES cells

To determine the phenotype of 5′HS2 core deletion within the endogenous murine β-globin locus, we deleted a region that is homologous to the 5′HS2 core in the human locus and compared the core deletion to a full 5′HS2 deletion. We employed HR and RMCE techniques to accomplish this. Figure 1A shows the exchange strategy. Figure 1B compares the sequences of the human HS core as deleted previously21 and the mouse HS2 core deleted in these experiments. This deletion was accomplished in 2 steps.

In the first step, the full HS2 element (core and flanking regions) was deleted by HR and replaced with a CMV-HyTK expression cassette flanked by inverted loxP binding sites. The extent of the deletion is identical to that of the full murine HS2 site deletion reported previously.14 In the second step, the CMV-HyTK cassette was replaced with either of 2 new sequences using the RMCE technique.27 The sequences we introduced at the modified β-globin locus were (1) a short polylinker, which mimics the full HS2 deletion (core and flanks), or (2) the 5′HS2 flanking sequences alone, thus generating the core deletion.

Note that the RMCE technique results in the introduction of the new sequence in either orientation; clones containing the flanking sequences in each orientation were distinguished by Southern blot. Figure 2 shows maps and Southern blots of the ES clones with 5′HS2 full deletion (ΔHS2 full) and 5′HS2 core deletion with the flanking sequence in the endogenous orientation (ΔHS2 core) and in the inverted orientation (ΔHS2 core invert).

Analysis of β-globin gene expression in 5′HS2 mutants via in vitro ES-cell differentiation

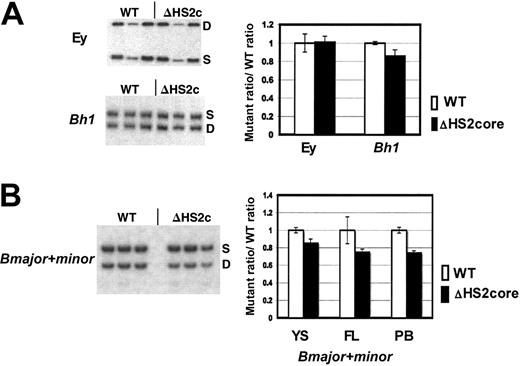

ES-cell clones harboring ΔHS2 core/S, ΔHS2 core (invert)/S, ΔHS2 full/S, and wild-type D/S genotypes were differentiated into primitive and definitive erythroid colonies. Total RNA was extracted from individual primitive and definitive erythroid colonies and assayed by RT-PCR for expression of β-like globin genes. Since all the mutations are made on the D allele and the DS2B ES cells carry both D and S alleles, the expression of globin genes from the mutated D allele is compared with expression of the corresponding wild-type gene from the S allele.14 Figure 3 presents quantitation for Bh1 and combined Bmajor/Bminor gene expression in the erythroid colonies from differentiated ΔHS2 core, ΔHS2 full, and the wild-type DS2B ES cells. In the ΔHS2 core erythroid colonies, Bh1 mRNA levels were not significantly different from Bh1 levels in wild-type colonies, whereas Bmajor/Bminor expression was 20% lower than wild-type levels (P < .05). In comparison, deletion of the full 5′HS2 site resulted again in no significant reduction of Bh1 and a 35% reduction in Bmajor/Bminor compared with the wild-type allele (P < .05). The reductions caused by the full site deletion were similar to those seen in mice with the full site deletion (Table 1).

β-Like globin gene expression in 5′HS2 core deletion mice. (A) Sample gels of Ey and Bh1 expression in yolk sac primitive erythroid cells. Graph of composite data from assays of Ey and Bh1 mRNA in WT/S and ΔHS2c/S yolk sac. WT values are the WT D/S ratio divided by itself to normalize to 1.0. The mutant/S ratio is divided by the prenormalization WT D/S ratio. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean for multiple individual embryos before normalization. (B) Sample gels of Bmaj+min expression in embryonic day 15.5 fetal liver of WT D/S and ΔHS2c/S mice. Graph of composite data from assay of Bmaj+min mRNA in WT D/S and ΔHS2c/S yolk sac (YS), fetal liver (FL), and adult peripheral blood (PB). Data normalization is done as described for Figure 3. Five or more embryos and 3 or more adult mice were assayed. ΔHS2c or ΔHS2core indicates the core deletion.

β-Like globin gene expression in 5′HS2 core deletion mice. (A) Sample gels of Ey and Bh1 expression in yolk sac primitive erythroid cells. Graph of composite data from assays of Ey and Bh1 mRNA in WT/S and ΔHS2c/S yolk sac. WT values are the WT D/S ratio divided by itself to normalize to 1.0. The mutant/S ratio is divided by the prenormalization WT D/S ratio. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean for multiple individual embryos before normalization. (B) Sample gels of Bmaj+min expression in embryonic day 15.5 fetal liver of WT D/S and ΔHS2c/S mice. Graph of composite data from assay of Bmaj+min mRNA in WT D/S and ΔHS2c/S yolk sac (YS), fetal liver (FL), and adult peripheral blood (PB). Data normalization is done as described for Figure 3. Five or more embryos and 3 or more adult mice were assayed. ΔHS2c or ΔHS2core indicates the core deletion.

DNaseI hypersensitive site formation in the HS2 core deletion mouse. Left panel is the Southern blot showing HS formation in WT mice. M indicates the molecular marker lane. The DNaseI concentration is 0 in the first lane and increases as shown by the triangle. The right panel is the Southern blot of HS formation in ΔHS2core mice. Expected size bands for HS sites or parent band are labeled.

DNaseI hypersensitive site formation in the HS2 core deletion mouse. Left panel is the Southern blot showing HS formation in WT mice. M indicates the molecular marker lane. The DNaseI concentration is 0 in the first lane and increases as shown by the triangle. The right panel is the Southern blot of HS formation in ΔHS2core mice. Expected size bands for HS sites or parent band are labeled.

Previous studies of deletions within the LCR led to models involving specific structural interactions among LCR HSs21 ; therefore, we were interested in evaluating the effect of further structural alterations within the LCR on β-globin gene expression. The RMCE technique results in the isolation of subclones containing the newly introduced HS2 flanking sequences in both orientations at the targeted integration site. RT-PCR analysis of in vitro-differentiated ES cells indicates that expression of neither Bh1 nor Bmajor/Bminor differs significantly between ΔHS2core and ΔHS2 core (invert) alleles (data not shown).

Generation and analysis of HS2 core deletion mice

While our in vitro studies do not demonstrate a large difference in expression upon deleting HS2 core versus core plus flanks, it is possible that the phenotype of certain mutations made in ES cells could be modified by transmission through the mouse germ line. To rule out this possibility, the ΔHS2 core ES clones were used to generate a mouse line with that mutation. Heterozygous and homozygous ΔHS2 core mutant mice were born at expected Mendelian frequencies (data not shown). In addition, erythrocytes of ΔHS2 core homozygote mice have no cellular evidence of thalassemia (data not shown).

β-Like globin gene expression was assayed through development using the D/S RT-PCR assay system. The expression of Ey, Bh1, and Bmajor and Bminor genes was assayed in embryonic d10.5 yolk sac, d14.5 fetal liver, and adult peripheral blood. In primitive cells, the ΔHS2 core mutation caused no change in Ey gene expression, and Bh1 expression was greater than 90% of wild-type expression (Figure 4A). The mutation also did not affect silencing since there was no expression of Ey or Bh1 in definitive cells (data not shown). Expression of the Bmajor and Bminor genes is approximately 80% of the very low wild-type levels in primitive cells in the yolk sac and approximately 75% of wild-type levels in fetal liver and adult peripheral blood definitive erythroid cells (all are statistically different from wild-type expression with P < .05; Figure 4B). The phenotype in mice with full 5′HS2 deletion compared with core 5′HS2 deletion is nearly identical (Table 1).

HS formation in HS2 core mutant mouse

Previous studies in which HSs of the endogenous murine LCR were deleted showed that the remaining HSs still formed.17 In human locus transgenic studies, however, deletion of HS core fragments led to the disappearance of the remaining DNaseI HSs within the human β-globin LCR.21,24 To determine how deletion of the 5′HS2 core fragment affects HS formation at the endogenous mouse locus, we analyzed the formation of 5′HS1, 2, and 3 in wild-type and ΔHS2 core mice. Figure 5 shows that while 5′HS1, 2, and 3 are present in wild-type mice, deletion of the 5′HS2 core abolishes the formation of 5′HS2, but 5′HS1 and HS3 still form. These results are identical to those from the mouse with a deletion of the full 5′HS2.17

Discussion

The function of the human β-globin LCR has been studied extensively in transgenic mice by using integrated human β-globin loci derived from linked cosmids, large YAC, or bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) constructs, which contain all of the genes along with the LCR. These studies support the conclusion that deletions limited to the core region of an HS result in a much more severe phenotype than larger HS deletions that include cores and flanking regions. This phenotype is primarily reflected in much lower β-globin gene-expression levels but also appears to involve generalized chromatin inaccessibility within the LCR, as shown by the lack of formation of the remaining HSs. The corresponding studies of the endogenous murine LCR have to this point been limited to large deletions encompassing both HS cores and flanking regions. The resulting phenotypes have resembled the milder phenotypes of full HS deletions within transgenic human loci, including moderate suppression of gene expression14-16,26 and little or no effect on formation of the remaining HSs.17

We have performed a deletion of the core region of 5′HS2 of the mouse β-globin LCR to more broadly test the hypothesis that deletion of a core is more suppressive than deletion of an entire HS. We find that at the endogenous murine β-globin locus, the phenotype of the core deletion is similar to that of the full HS deletion both in terms of expression levels (Table 1) and in terms of formation of the remaining HSs (Figure 5). Thus, our studies contrast markedly with those using human transgenes (Table 1).

Human β-globin transgenes are (necessarily) analyzed in ectopic genomic locations, whereas the endogenous mouse locus has only been studied in the genomic location where it evolved. Despite the prevailing belief that the LCR fully blocks position effects, a transgene with a normal LCR can occasionally be found to exhibit moderate to severe position effects,30-32 including the variegation associated with classic position effects.33 Previous studies of HS deletions within human β-globin locus transgenes have supported the idea that deletion of an HS further predisposes the transgene to position effects.25 Potentially, human transgenes with core deletions are more susceptible to position effects than transgenes with full site deletions. Thus, the mechanisms by which a large HS deletion and a core deletion affect transgenic β-globin expression may be the same and only differ in magnitude.

The explanation previously offered for the greater magnitude of the HS core deletions is that an LCR “holocomplex” forms normally but has a dominant-negative structure when an HS core is missing. The associated hypothesis for why transgenes with full HS deletions are less suppressed is that with the full HS deleted, the LCR can take an alternative holocomplex structure that accommodates the lost HS.21 To date, however, there exists no molecular or biochemical evidence for an LCR holocomplex. In addition, the dominant-negative “holocomplex” structural model appears irrelevant with regard to differences between HS core and larger HS deletions: remaining LCR HSs fail to form at all in transgenes with core HS deletions, suggesting that normal LCR structure, whatever it may be, is completely abolished. A loss of HS formation implies that the usual array of transcription factors that binds to the HS are not bound, and the most likely explanation for this is that the chromatin is closed. In this case the dominant-negative structure appears to be a complete loss of normal structure rather than a subtle change.

Silencing of β-globin locus-carrying transgenes, whether those with wild-type LCRs, entire HS deletions, or core HS deletions, are associated with distinct changes in chromatin structure such that the locus appears to be “closed” chromatin, and formation of all HSs in the LCR is weak or completely lost.21,24,25 Deletion of HSs at the mouse locus does not suppress hypersensitivity of the remaining HS and closed chromatin does not form in the endogenous mouse locus even when the entire LCR is deleted.8,9 This implies either that additional erythroid-specific activating elements are present at the endogenous locus or that the endogenous locus is simply not repressive in erythroid cells for other reasons. Presumably, if the mouse locus were itself examined at ectopic sites from within the mouse genome, it would be subject to the same position effects observed for the human locus. The alternative is that the mouse and human β-globin LCRs function in fundamentally different ways. We cannot rule out this possibility but the extensive DNA sequence similarity between LCR HSs in mammals from mouse to human, coupled with the similar organization of the β-globin locus in all mammals, argues against it. It should be noted, however, that the homology between mouse and human is only found in the HSs themselves, and the intervening sequences have no homology between these LCRs.

One plausible interpretation of these composite results focuses on the realization that the LCR has both chromatin opening activity and expression-enhancing activity. The endogenous mouse locus does not appear to require the chromatin opening activity whereas in most integration sites transgenes of the human locus require that activity in order to manifest the expression enhancement. Perhaps the core deletion does in fact act to suppress the chromatin opening activity whereas the full site deletion has less influence on this activity. Experiments in which a transgene is manipulated in a single genomic location to measure activity of wild-type, core deletion, and full deletion transgenes in a single site would verify this possibility and open a system for understanding the basis of the effect.

There are also technical implications of this study. Similarity of phenotypic results from globin locus mutations studied in differentiated ES cells or in mice supports the belief that ES-cell differentiation is an appropriate assay system for studying globin locus modifications. This extends similar findings in which the entire LCR was deleted and assayed in differentiated ES cells and in derived mice. In addition, the studies presented here confirm the efficiency with which RMCE can be used to modify a site in ES cells and demonstrate that following an RMCE reaction ES cells are still able to contribute to the germ line and produce mice.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 27, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2308.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 DK54071 (S.F.) and R37 DK44746 (M.G.).

X.H., M.B., and S.F. designed experiments, carried out experiments, and wrote the paper; M.A.B. contributed reagents and wrote the paper; J.F. carried out experiments; and M.G. designed experiments and wrote the paper.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We would like to acknowledge the Dartmouth Transgenic Facility for production of the mutant mice described here.