CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells control immunologic tolerance and antitumor immune responses. Therefore, in vivo modification of Treg function by immunosuppressant drugs has broad implications for transplantation biology, autoimmunity, and vaccination strategies. In vivo bioluminescence imaging demonstrated reduced early proliferation of donor-derived luciferase-labeled conventional T cells in animals treated with Treg cells after major histocompatibility complex mismatch bone marrow transplantation. Combining Treg cells with cyclosporine A (CSA), but not rapamycin (RAPA) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), suppressed Treg function assessed by increased T-cell proliferation, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) severity, and reduced survival. Expansion of Treg and FoxP3 expression within this population was lowest in conjunction with CSA, suggesting that calcineurin-dependent interleukin 2 (IL-2) production is critically required for Treg cells in vivo. The functional defect of Treg cells after CSA exposure could be reversed by exogenous IL-2. Further, the Treg plus RAPA combination preserved graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effector function against leukemia cells. Our data indicate that RAPA and MMF rather than CSA preserve function of Treg cells in pathologic immune responses such as GVHD without weakening the GVT effect. (Blood. 2006;108:390-399)

Introduction

Naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are critical in the reduction of experimental acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD)1-3 but also provide immune privilege for malignant disease.4 Therefore, affecting Treg-cell function in vivo by different immunosuppressant drugs has relevance for transplantation biology and may be useful to enhance antitumor vaccination strategies. We have previously shown that Treg cells are capable of suppressing experimental aGVHD while preserving the beneficial graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect.1 These favorable effects and the observation that murine Treg cells share functional characteristics with their human counterparts have fueled interest in exploring cell-based immunotherapy in clinical trials to further investigate the capability of Treg cells to prevent aGVHD or treat autoimmunity; however, there is little information on the impact of immunosuppressant drugs on Treg-cell function.

Treg suppressor function has been demonstrated to be critically dependent on the presence of interleukin 2 (IL-2)5-7 and activation by T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement.8,9 Recently, IL-2 signaling has been shown to be critical for survival of FoxP3+ Treg cells in vivo.10-12

We therefore compared the relevance of calcineurin-dependent IL-2 production13 versus mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway activity14 versus inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase enzyme activity15 for Treg function in vivo, by using the commonly applied immunosuppressant drugs cyclosporine A (CSA), rapamycin (RAPA), and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).

Using a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II mismatch bone marrow transplantation (BMT) model, we observed that trafficking of luciferase (luc+)-expressing Treg cells was not altered by the different immunosuppressant drugs and proliferation was only slightly affected. However, CSA administration led to significantly reduced Treg function in vivo. Mechanistically we have identified that CSA acts by reducing the production of IL-2 because exogenous IL-2 can overcome reduced FoxP3+ expression and the functional defect in Treg cells induced by CSA.

Materials and methods

Mice

FVB/N (H-2kq, Thy-1.1), C57B/6 (H-2kb, Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.2), and Balb/c mice (H-2kd, Thy-1.2) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA). Mice were used between 6 and 12 weeks of age. Only sex-matched combinations were used for transplantation experiments. The luciferase-expressing (luc+) transgenic FVB/N line was generated as previously described.16 Male heterozygous luc+ offspring of the transgenic founder line FVB-L2G85 were used for all transplantation experiments. All animal protocols were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Laboratory Animals at Stanford University.

Immunosuppressive treatment

For in vivo studies, CSA (Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, OH) and MMF (Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ) were dissolved by suspension in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). RAPA (Wyeth-Ayerst, Princeton, NJ) was dissolved in carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt (C-5013; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and polysorbate 80 (P-8074; Sigma-Aldrich). RAPA stock solution was stored at 4°C in the dark in distilled water according to the manufacturer's instructions. Injections were given intraperitoneally once daily and started on day 0. Dosage was adjusted to the body weight every other day. Mycophenolic acid (MPA; Sigma-Aldrich), the active metabolite of MMF, was used for in vitro experiments. Immunosuppressive treatment was continued until death or end of the observation period (day 100).

Flow cytometric cell purification and analysis

The following antibodies were used for flow cytometric analysis: unconjugated anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8α (53-6.7), CD25 (PC61), CD11c (M1/70), CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2), H-2Kq (KH114), H-2Kd (34-2-12), Thy-1.1 (H1S51), Thy-1.2 (53-2.1), and Foxp3 (FJK-16). All reagents were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA) and eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). Staining was performed in the presence of purified anti-CD16/32 at saturation to block unspecific staining. Propidium iodide (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was added prior to analysis to exclude dead cells. Apoptosis was measured by annexin V staining. All analytic flow cytometry was done on a modified dual laser LSRScan (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Diego, CA).

Cell isolation and sorting

Single-cell suspensions from cervical lymph nodes (cLNs), axillary lymph nodes (aLNs), inguinal lymph nodes (iLNs), mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs), and spleens were enriched for CD25+ cells after sequential staining with anti-CD25 PE (BD PharMingen) and anti-PE magnetic beads using the auto-magnetically activated cell sorting (autoMACS) system (POSSEL program, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). CD25+ cells were then stained with anti-CD4 allophycocyanin and sorted on a MoFlow cell sorter (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) for the CD25high population (15%-20% of the enriched CD25+ cells). This sorting strategy yielded 96% or more CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells.

T-cell-depleted bone marrow (TCD-BM) was obtained through negative depletion using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). For transplantation of conventional and luc+ T-cell subsets, splenic single-cell suspensions from FVB-L2G85 mice were enriched with CD4/CD8-conjugated magnetic beads using the autoMACS system (POSSEL_D, Miltenyi Biotec). After enrichment, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells reached more than 90% purity.

Real-time quantitative PCR for Foxp3

Total RNA was isolated from fresh cell pellets using the RNeasy MiniKit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and gDNA was eliminated by digestion with a modified proprietary DNase (DNA-free; Ambion, Austin, TX). Total RNA (500 ng) was mixed with dT16 primer in a volume of 11 μL, incubated at 65°C for 10 minutes, and immediately put on ice. Following addition of 100 U Superscript II reverse transcriptase (RT; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) reverse transcription was performed for 2 hours at 42°C in 1 × RT reaction buffer (Gibco), 10 μM DTT, 500 μM dNTP (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA) with 2.5 μM dT16 primer in a volume of 20 μL. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in a final volume of 20 μL with cDNA prepared from 20 ng RNA and a final concentration of 1 × SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI, Foster City, CA) and 200 nM of each primer (sequences: FoxP3 forward, GGAGCCGCAAGCTAAAAGC; FoxP3 reverse, TGCCTTCGTGCCCACTG; GAPDH forward, GTCCTGAAGTATGTCGTGGAGTCTAC; and GAPDH reverse, GGCCCCGGCCTTCTC). The reaction was run in an ABI 7700 Sequence Detection System with the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 2 minutes, 94°C for 10 minutes, then 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 60 seconds. For each gene a standard curve was prepared and triplicate measurements were performed for each sample.

Immunofluorescence

Sorted cells were fixed for 10 minutes to slides (Sigma) with ice-cold acetone. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in PBS containing 10% FCS and were incubated 30 minutes at 4°C with a monoclonal rat anti-mouse-Foxp3 antibody (FJK-16s, eBioscience) and after PBS washing with a secondary goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor 546 antibody (A11081, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 minutes. Cells were washed with PBS and were incubated for 5 minutes with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for nuclei stain.

TNF-α and IFN-γ ELISA

Serum was collected from Balb/c recipients on day 7 after transplantation. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Briefly, samples were diluted 1:2 to 1:5, and TNF-α or IFN-γ was captured by the specific primary monoclonal antibody (mAb) precoated on the microplate and detected by horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary mAbs. Plates were read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (model Spectra Max 190; Bio-Rad Labs, Hercules, CA). Recombinant murine TNF-α and murine IFN-γ (BD PharMingen) were used as standards. Samples and standards were run in duplicate, and the sensitivity of the assays was 16 to 20 pg/mL for each cytokine, depending on the sample dilution.

CFSE-based cell proliferation

For cell-proliferation analysis, T cells (1 × 107/mL) were resuspended in plain PBS and stained with Vybrant carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFDA SE) tracer kit (Molecular Probes) at a final concentration of 5 μM for exactly 6 minutes at 37°C. Immediately after staining, cells were washed in 5 volumes of ice-cold RPMI plus 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Life Sciences, Grand Island, NY) twice, resuspended in PBS, and counted before use in an in vitro assay or intravenous injection. The proportion of CFSE+ cells proliferating in vitro was calculated as previously described.17

Mixed leukocyte reaction for Treg suppressor function

Treg cells (CD4+CD25high+H-2kb+Thy-1.1+) were incubated for 96 hours with γ-irradiated (30 Gy) antigen-presenting cells (APCs; CD11c+H-2kd+) and CFSE+-labeled conventional T (TCONV) cells (CD4+CD25-H-k2b+Thy-1.2+), with each population 2 × 105 cells. Cell division was monitored by levels of CFSE dilution. Cultures were evaluated in triplicate in 96-well flat-bottom plates in a total volume of 200 μL. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS, 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 1% nonessential amino acids, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Gibco), and 5 μg/mL 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich).

GVHD model

To induce aGVHD, Balb/c recipients received 5 × 106 TCD-BM cells on day 0 plus 1.6 × 106 T cells from FVB/N donors on day 2 after lethal irradiation with 800 cGy as described previously.18 Treg cells (8 × 105 CD4+CD25high) were coinjected with TCD-BM on day 0 resulting in a 1:2 ratio (Treg/TCONV). Mice were kept on antibiotic water (sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim; Schein Pharmaceutical, Danbury, CT) for the first 30 days. For conventional histology, mice were killed 5 and 15 days after cell transfer. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded tissue sections was performed according to standard protocols. Histologic GVHD scoring was performed according to a previously published system19 by a pathologist (S.S.) who received coded paraffin-embedded tissue samples of liver and small and large bowel and was blinded to the treatment groups.

In vivo and ex vivo bioluminescence imaging

In vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was performed as previously described.18 Briefly, mice were injected intraperitoneally with luciferin (10 μg/g body weight). Ten minutes later mice were imaged using an IVIS200 charge-coupled device (CCD) imaging system (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) for 5 minutes. Imaging data were analyzed and quantified with Living Image Software (Xenogen) and IgorProCarbon (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

Tumor model

To investigate GVT activity of transferred donor T cells, we used A20-luc/yfp B-cell leukemia cells that have been previously demonstrated to migrate primarily to the bone marrow with secondary infiltration of spleen and other lymphoid organs when injected intravenously at the time of BMT.1,20 Animals were given injections with A20-luc/yfp-leukemia cells 2 days prior to administration of the TCONV cells to allow the tumor to home and establish. Tumor growth was analyzed by BLI, quantification of yfp-expressing cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and H&E histology.

Statistical analysis

Differences in animal survival (Kaplan-Meier survival curves) were analyzed by log-rank test. Differences in proliferation of TCONV cells, FoxP3 expression, GVHD histopathology score, and serum cytokine levels were analyzed using the 2-tailed Student t test.

Results

In vitro effect of CSA, RAPA, and MPA on Treg suppressor function

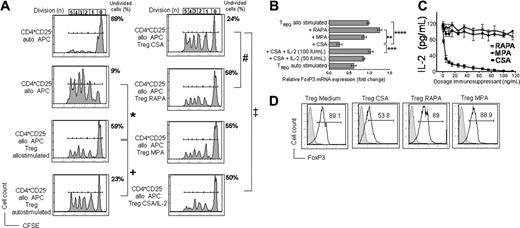

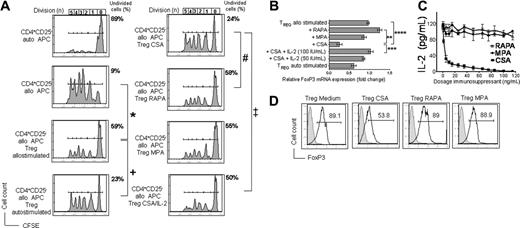

Alloantigen-activated Treg cells significantly reduced alloantigen-driven proliferation of CD4+CD25- TCONV cells (Figure 1A left column), consistent with previous reports of ex vivo activated murine Treg cells.21 Importantly, RAPA, MPA, the active metabolite of MMF, and CSA-exposed murine Treg cells maintained differential degrees of suppressor function in vitro (Figure 1A right column). Treg cells derived from cultures containing CSA were less suppressive as compared to Treg cells exposed to RAPA or MPA (Figure 1A right column). Importantly, the decreased level of suppression correlated with reduced FoxP3 mRNA levels in Treg cells exposed to CSA (Figure 1B). Our finding that allostimulation increases FoxP3 expression is in line with results reported by Fontenot et al, who showed an increase of FoxP3 expression in CD4+CD25+ T cells after TCR ligation.11

In vitro effects of CSA, RAPA, and MPA on Treg cells. In vitro effects of CSA, RAPA, and MPA on allostimulated Treg cells with respect to suppressor function (A), FoxP3 expression (B,D), and IL-2 levels in the primary coculture (C). (A) Fresh isolated C57B/6 Treg cells (CD4+CD25highH-2kb+) were incubated with Balb/c APCs (CD11c H-2kd) with CSA (100 ng/mL), RAPA (10 ng/mL), or MPA (50 ng/mL). Treg cells were reisolated by sorting for CD4+CD25highH-2kb+ cells after 72 hours of primary coculture. Reisolated Treg cells were then incubated for 96 hours with γ-irradiated (30 Gy) APCs (CD11c+H-2kd+) and CFSE-labeled TCONV cells (CD4+CD25-H-2kb+Thy-1.2+), with each population 2 × 105 cells. Cell division was monitored by levels of CFSE dilution. The congenic markers Thy-1.1 and Thy-1.2 were used to distinguish between Treg and TCONV cells, respectively. Histograms show the FACS profile of CFSE+ TCONV cells. Numbers of events in each cell division (n) are indicated below the respective peak. The percentage of undivided CD4+CFSE+ cells in each culture condition is indicated next to the right upper corner of the respective histogram. One representative experiment of 4 is presented. Allostimulated Treg cells suppress alloantigen-driven expansion of CFSE+ TCONV (*) significantly more strongly than autostimulated Treg cells (+; P = .027). CSA-exposed Treg cells are still suppressive, but significantly less as compared to RAPA (#P = .031) and addition of IL-2 (50 IU/mL) to the activation culture restores Treg function partially (‡; P = .037). (B) Relative FoxP3 mRNA expression level in Treg cells (H-2kb+) exposed to allogeneic APCs (H-2kd+) alone or in conjunction with RAPA (10 ng/mL), MPA (50 ng/mL), CSA (100 ng/mL), or CSA (100 ng/mL) plus IL-2 or exposed to autologous APCs (H-2kd). The increase of FoxP3 expression in Treg cells during allostimulation is reduced by CSA addition and restored by IL-2. Data represent means ± SD of triplicates (**P = .004; ***P = .008; ****P = .007). (C) IL-2 concentrations measured by ELISA in supernatants from the following cocultures are depicted (y-axis): Treg cells (H-2kb) incubated with APCs (H-2kd) and CSA (▪), RAPA (▵), or MPA (•)at different concentrations (x-axis) after 72 hours. CSA but not RAPA or MPA reduces IL-2 levels in the Treg activation culture in a dose-dependent manner. (D) Histograms depict the intracellular expression profile of FoxP3 in live-gated Treg cells exposed to medium, CSA (100 ng/mL), RAPA (10 ng/mL), or MPA (50 ng/mL) for 72 hours (filled histogram, unstained cells; open histogram, FoxP3 staining). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for FoxP3 expression is significantly lower in Treg cells reisolated from CSA (213 ± 24) as compared to cultures containing RAPA (412 ± 42) or MPA (392 ± 31; P < .05).

In vitro effects of CSA, RAPA, and MPA on Treg cells. In vitro effects of CSA, RAPA, and MPA on allostimulated Treg cells with respect to suppressor function (A), FoxP3 expression (B,D), and IL-2 levels in the primary coculture (C). (A) Fresh isolated C57B/6 Treg cells (CD4+CD25highH-2kb+) were incubated with Balb/c APCs (CD11c H-2kd) with CSA (100 ng/mL), RAPA (10 ng/mL), or MPA (50 ng/mL). Treg cells were reisolated by sorting for CD4+CD25highH-2kb+ cells after 72 hours of primary coculture. Reisolated Treg cells were then incubated for 96 hours with γ-irradiated (30 Gy) APCs (CD11c+H-2kd+) and CFSE-labeled TCONV cells (CD4+CD25-H-2kb+Thy-1.2+), with each population 2 × 105 cells. Cell division was monitored by levels of CFSE dilution. The congenic markers Thy-1.1 and Thy-1.2 were used to distinguish between Treg and TCONV cells, respectively. Histograms show the FACS profile of CFSE+ TCONV cells. Numbers of events in each cell division (n) are indicated below the respective peak. The percentage of undivided CD4+CFSE+ cells in each culture condition is indicated next to the right upper corner of the respective histogram. One representative experiment of 4 is presented. Allostimulated Treg cells suppress alloantigen-driven expansion of CFSE+ TCONV (*) significantly more strongly than autostimulated Treg cells (+; P = .027). CSA-exposed Treg cells are still suppressive, but significantly less as compared to RAPA (#P = .031) and addition of IL-2 (50 IU/mL) to the activation culture restores Treg function partially (‡; P = .037). (B) Relative FoxP3 mRNA expression level in Treg cells (H-2kb+) exposed to allogeneic APCs (H-2kd+) alone or in conjunction with RAPA (10 ng/mL), MPA (50 ng/mL), CSA (100 ng/mL), or CSA (100 ng/mL) plus IL-2 or exposed to autologous APCs (H-2kd). The increase of FoxP3 expression in Treg cells during allostimulation is reduced by CSA addition and restored by IL-2. Data represent means ± SD of triplicates (**P = .004; ***P = .008; ****P = .007). (C) IL-2 concentrations measured by ELISA in supernatants from the following cocultures are depicted (y-axis): Treg cells (H-2kb) incubated with APCs (H-2kd) and CSA (▪), RAPA (▵), or MPA (•)at different concentrations (x-axis) after 72 hours. CSA but not RAPA or MPA reduces IL-2 levels in the Treg activation culture in a dose-dependent manner. (D) Histograms depict the intracellular expression profile of FoxP3 in live-gated Treg cells exposed to medium, CSA (100 ng/mL), RAPA (10 ng/mL), or MPA (50 ng/mL) for 72 hours (filled histogram, unstained cells; open histogram, FoxP3 staining). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for FoxP3 expression is significantly lower in Treg cells reisolated from CSA (213 ± 24) as compared to cultures containing RAPA (412 ± 42) or MPA (392 ± 31; P < .05).

Interestingly, reduced Treg function in the presence of CSA, as measured by percentage of undivided TCONV cells, could be reversed from 24% ± 2.7% to 50% ± 3.4% by the addition of IL-2 to the primary stimulation culture (‡ in Figure 1A right column), which again correlated with FoxP3 mRNA expression (Figure 1B). To examine whether the Treg stimulation culture was depleted of IL-2 in the presence of different immunosuppressants, the cytokine was measured in the culture supernatants at various dosages. Whereas RAPA and MPA had only a minor impact on the IL-2 level in the primary Treg activation culture, the cytokine was reduced dose dependently in the presence of CSA (Figure 1C). In contrast to IL-2 the cytokines IL-7 and IL-15 could not reverse the CSA effect (data not shown). Intracellular FoxP3 staining confirmed quantitative real-time PCR results and indicated that CSA exposure induced a shift toward lower FoxP3 expression and not 2 distinct FoxP3high versus FoxP3low Treg populations (Figure 1D). The experiments were reproducible in an eGFP-based Treg reisolation system (data not shown).

CSA, RAPA, and MMF reduce aGVHD in a dose-dependent manner

To define the impact of different immunosuppressant drug doses on the expansion of donor-derived TCONV cells and aGVHD lethality, CSA, RAPA, and MMF were investigated in a recently described GVHD model18 where CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from luciferase transgenic FVB/N animals (H-2kq) are transferred into MHC class I and class II mismatched BALB/c recipients (H-2kd). Doses of the immunosuppressants were chosen according to previous publications on murine GVHD models for CSA,22-24 RAPA,22,25 and MMF.26

Effects of different doses of CSA, RAPA, and MMF on GVHD-related mortality. Data from 3 independent experiments are combined. (A) Percentage survival of animals receiving CSA 10 mg/kg (□, n = 12), CSA 50 mg/kg (▪, n = 12), or PBS (⋄, n = 12). The higher CSA dose improves survival (▪ versus ⋄, P = 0.032). (B) Percentage survival of animals receiving RAPA 0.5 mg/kg (○, n = 12), RAPA 1.5 mg/kg (•, n = 12), or PBS (⋄, n = 12). The higher RAPA dose improves survival (• versus ⋄, P = 0.029). (C) Percentage survival of animals receiving MMF 90 mg/kg (▵, n = 12), MMF 200 mg/kg (▴, n = 12), or PBS (⋄, n = 12), not significant (NS). Control animals received TCD-BM only (*). (D) Distribution of donor derived luc+ TCONV cells in Balb/c recipients at day 5 after BMT with coadministration of different doses of CSA (top row), RAPA (middle row), and MMFl (bottom row). At this time point the major TCONV expansion is found in cLNs, GIT, and SPL. Although the localization pattern of TCONV is conserved, proliferation is gradually reduced when different doses of immunosuppressants are administered.

Effects of different doses of CSA, RAPA, and MMF on GVHD-related mortality. Data from 3 independent experiments are combined. (A) Percentage survival of animals receiving CSA 10 mg/kg (□, n = 12), CSA 50 mg/kg (▪, n = 12), or PBS (⋄, n = 12). The higher CSA dose improves survival (▪ versus ⋄, P = 0.032). (B) Percentage survival of animals receiving RAPA 0.5 mg/kg (○, n = 12), RAPA 1.5 mg/kg (•, n = 12), or PBS (⋄, n = 12). The higher RAPA dose improves survival (• versus ⋄, P = 0.029). (C) Percentage survival of animals receiving MMF 90 mg/kg (▵, n = 12), MMF 200 mg/kg (▴, n = 12), or PBS (⋄, n = 12), not significant (NS). Control animals received TCD-BM only (*). (D) Distribution of donor derived luc+ TCONV cells in Balb/c recipients at day 5 after BMT with coadministration of different doses of CSA (top row), RAPA (middle row), and MMFl (bottom row). At this time point the major TCONV expansion is found in cLNs, GIT, and SPL. Although the localization pattern of TCONV is conserved, proliferation is gradually reduced when different doses of immunosuppressants are administered.

Higher doses of CSA (50 mg/kg) and RAPA (1.5 mg/kg) were associated with a significantly improved survival as compared to animals receiving TCONV and PBS or the lower dose of the respective immunosuppressant (Figure 2A-B). Administration of the higher MMF dose (200 mg/kg) did not result in improved survival as compared to PBS injection (Figure 2C). Lower doses of CSA, RAPA, and MMF were associated with aGVHD-related lethality within the first 30 days, indicating the modest impact of the immunosuppressants at these dosages on aGVHD, and were therefore chosen for further adoptive Treg transfer studies. The suppressive impact of CSA, RAPA, and MMF on the proliferation of luc+ CD4+ and CD8+ donor T cells was visualized by BLI (Figure 2D). Interestingly, the homing of TCONV cells to the cLNs, spleen (SPL), and gastrointestinal tract (GIT) was conserved in the presence of the different immunosuppressants, whereas TCONV expansion was gradually reduced according to dosing (Figure 2D). To exclude that the BLI signal only reflects the impact of the immunosuppressants on TCONV-cell expansion, we performed a titration study with different doses of the immunosuppressants with respect to signal intensity. We found that the immunosuppressant drugs at the following doses, CSA 10 mg/kg, RAPA 0.5 mg/kg, MMF 90 mg/kg, had no significant impact on the BLI signal as compared to PBS (data not shown).

Impact of immunosuppressants on adoptively transferred Treg cells with respect to GVHD-related morbidity, mortality, and TCONV expansion

We tested the effect of the immunosuppressants CSA, RAPA, and MMF on Treg function in our lethal aGVHD model,18 where Treg transfer is essential for survival. We have found that Treg cells are most effective when given prior to TCONV (V.H.N., unpublished data, May 2005). Therefore, we administered Treg cells together with TCD-BM on day 0, whereas TCONV cells were consistently given on day 2 after transplantation.

Mice given TCD-BM alone appeared healthy, and more than 90% of the animals survived for at least 70 days. Mice that received TCONV cells along with TCD-BM developed severe GVHD signs including reduced activity, hunched posture, ruffled fur, diarrhea, and weight loss and all animals died within 30 days after transplantation. Treg-cell cotransfer reduced GVHD-related death after BMT and more than 75% survived longer than 70 days. These data confirm the potential of Treg cells to suppress aGVHD after major mismatch BMT.

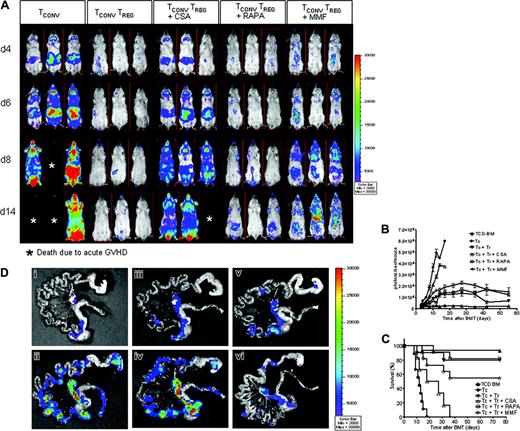

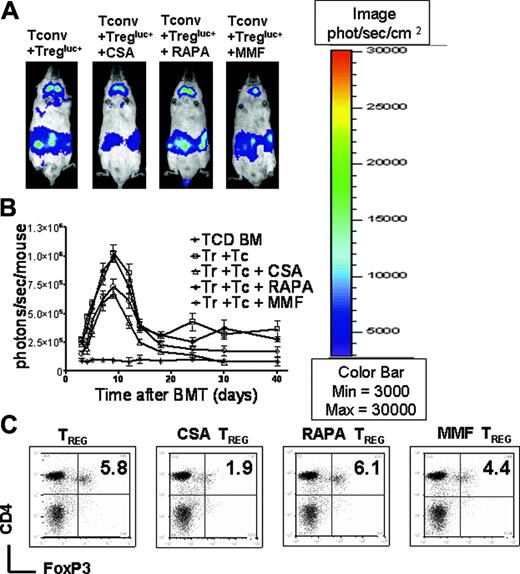

To examine whether donor-derived Treg cells would prevent expansion of TCONV cells in living animals in the presence of different immunosuppressants, we used luc+ TCONV cells. Mice that received TCD-BM plus TCONV cells displayed vigorous TCONV expansion in contrast to animals that received additional Treg cells (Figure 3A). By day 8, TCONV cells were distributed throughout the animal and accumulated in skin, lymph nodes, and GIT (Figure 3A first column from left). Animals receiving Treg cells and CSA showed a reduced expansion of TCONV cells as compared to the group that received TCONV cells alone but significantly higher signal intensity as compared to groups receiving Treg cells plus RAPA or Treg cells plus MMF in serial whole-body BLI (Figure 3A-B). Animals receiving CSA along with Treg cells had significantly reduced overall survival as compared to Treg plus PBS, Treg plus RAPA, and Treg plus MMF as shown in Figure 3C.

CSA but not RAPA or MMF interferes with Treg suppressor function in vivo. Expansion of luc+ donor TCONV cells in animals receiving TCONV cells alone or TCONV and Treg cells or TCONV and Treg cells in conjunction with CSA (10 mg/kg), RAPA (0.5 mg/kg), or MMF (90 mg/kg) as shown for 3 representative animals at days 4, 6, 8, and 14 after BMT (A) and as quantified by emitted photons over total body area at serial time points after BMT (B). GVHD was induced as described in “Materials and methods.” Data from 3 independent experiments are combined. (A) Proliferation of luc+ TCONV (first column from left) is reduced by cotransfer of Treg cells (second column from left). Addition of CSA reduces the suppressive effect of Treg cells (third column from left). In contrast RAPA allows for Treg function (fourth column from left) and MMF has minimal impact (fifth column from left). (B) TCD-BM (▴,n = 15), with TCONV cells (•,n = 15), with TCONV and Treg cells (▾,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and CSA (▵,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (□,n = 10), or with TCONV and Treg cells and MMF (○,n = 10). Signal intensity is significantly higher in animals receiving TCONV and Treg cells and CSA as compared to RAPA (▵ versus □, P = .001, day 14) and MMF (▵ versus ○, P = .009, day 14). (C) Percentage survival of Balb/c recipients is significantly lower when combining Treg cells with CSA as compared to RAPA (▵ versus □, P = .001) or MMF (▵ versus ○, P = .007). (D) Expansion of luc+ TCONV cells at day 10 after BMT in the GIT. (Di) Background signal in the GIT of animals having received only TCD-BM without any luc+ cells. Proliferation of TCONV cells in mLNs and the GIT (Dii) is reduced by cotransfer of Treg cells (Diii). Addition of CSA reduces the protective effect of Treg cells (Div). RAPA (Dv) and MMF (Dvi) do not abrogate Treg suppression of TCONV proliferation in vivo.

CSA but not RAPA or MMF interferes with Treg suppressor function in vivo. Expansion of luc+ donor TCONV cells in animals receiving TCONV cells alone or TCONV and Treg cells or TCONV and Treg cells in conjunction with CSA (10 mg/kg), RAPA (0.5 mg/kg), or MMF (90 mg/kg) as shown for 3 representative animals at days 4, 6, 8, and 14 after BMT (A) and as quantified by emitted photons over total body area at serial time points after BMT (B). GVHD was induced as described in “Materials and methods.” Data from 3 independent experiments are combined. (A) Proliferation of luc+ TCONV (first column from left) is reduced by cotransfer of Treg cells (second column from left). Addition of CSA reduces the suppressive effect of Treg cells (third column from left). In contrast RAPA allows for Treg function (fourth column from left) and MMF has minimal impact (fifth column from left). (B) TCD-BM (▴,n = 15), with TCONV cells (•,n = 15), with TCONV and Treg cells (▾,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and CSA (▵,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (□,n = 10), or with TCONV and Treg cells and MMF (○,n = 10). Signal intensity is significantly higher in animals receiving TCONV and Treg cells and CSA as compared to RAPA (▵ versus □, P = .001, day 14) and MMF (▵ versus ○, P = .009, day 14). (C) Percentage survival of Balb/c recipients is significantly lower when combining Treg cells with CSA as compared to RAPA (▵ versus □, P = .001) or MMF (▵ versus ○, P = .007). (D) Expansion of luc+ TCONV cells at day 10 after BMT in the GIT. (Di) Background signal in the GIT of animals having received only TCD-BM without any luc+ cells. Proliferation of TCONV cells in mLNs and the GIT (Dii) is reduced by cotransfer of Treg cells (Diii). Addition of CSA reduces the protective effect of Treg cells (Div). RAPA (Dv) and MMF (Dvi) do not abrogate Treg suppression of TCONV proliferation in vivo.

To more precisely localize the abdominal BLI signal, ex vivo imaging of the GIT as a GVHD target organ was performed. The adoptive transfer of Treg cells reduced the ex vivo signal of luc+ TCONV cells in the GIT and the mLNs, an effect that was maintained in the presence of RAPA and MMF and reduced when Treg cells were given in conjunction with CSA (Figure 3D).

Proinflammatory cytokine production and histopathologic GVHD scoring

IL-2 serum levels were below the detectable level in any of the animals given transplants, but there was a significant increase in serum IFN-γ in animals that received TCONV cells and developed GVHD. IFN-γ levels were significantly lower in animals that received Treg cells and TCONV cells plus RAPA as compared to Treg cells and TCONV cells plus CSA (Figure 4A). The same trend was observed for serum TNF-α although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4B). These data indicate that Treg cells alone or in combination with RAPA reduce proliferation and accumulation of proinflammatory cytokines after BMT. Histopathologic scoring of a total of 36 animals (6 from each group) demonstrated a significantly higher GVHD score (*P < .05) in the group that received Treg cells along with CSA as compared to PBS, RAPA, or MMF (Figure 4C).

Expansion of adoptively transferred FoxP3+CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in the irradiated recipient

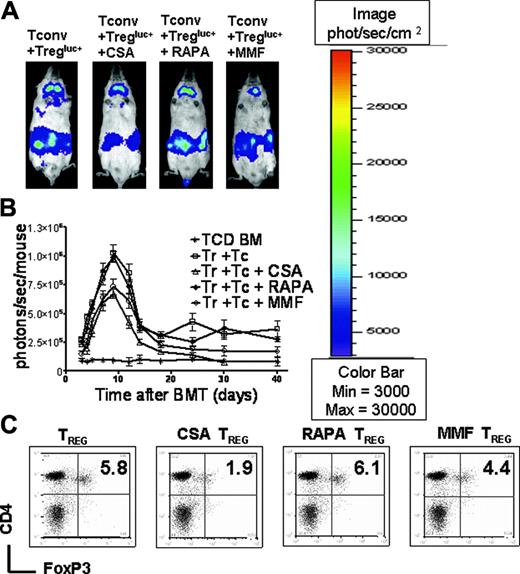

To investigate the impact of the different immunosuppressants on Treg expansion, we used Treg cells derived from luc+ animals, which allows for monitoring of in vivo expansion. Serial BLI showed that none of the immunosuppressants completely abrogated the expansion of the adoptively transferred Treg cells (Figure 5A-B). Administration of CSA was associated with the lowest signal intensity indicating reduced Treg expansion; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Serum IFN-γ and TNF-α levels. Serum was collected on day 7 after transplantation of Balb/c recipients as indicated for each individual bar (each 5 animals). Data are derived from one of 2 independent experiments. (A) Animals receiving Treg cells in conjunction with RAPA have a significantly lower IFN-γ serum level as compared with Treg cells plus CSA, *P = .02. (B) TNF-α levels are lowest in animals receiving TCD-BM. Differences between the groups that receive TCONV/Treg cells in conjunction with different immunosuppressants are not statistically significantly different. (C) The histopathologic score for the different groups is shown. Analysis included the large bowel, small bowel, and liver from recipients on days 5 and 15. Coded tissue samples were scored by a pathologist blinded to the treatment groups as described in “Materials and methods.”

Serum IFN-γ and TNF-α levels. Serum was collected on day 7 after transplantation of Balb/c recipients as indicated for each individual bar (each 5 animals). Data are derived from one of 2 independent experiments. (A) Animals receiving Treg cells in conjunction with RAPA have a significantly lower IFN-γ serum level as compared with Treg cells plus CSA, *P = .02. (B) TNF-α levels are lowest in animals receiving TCD-BM. Differences between the groups that receive TCONV/Treg cells in conjunction with different immunosuppressants are not statistically significantly different. (C) The histopathologic score for the different groups is shown. Analysis included the large bowel, small bowel, and liver from recipients on days 5 and 15. Coded tissue samples were scored by a pathologist blinded to the treatment groups as described in “Materials and methods.”

To correlate these results with the level of FoxP3 expression, we quantified donor-derived CD4+FoxP3+ T cells from spleen, cLNs, and mLNs by FACS analysis at various time points after transplantation. Interestingly, the frequency of donor derived H-2kq+CD4+FoxP3+ cells in Balb/c recipients having received TCONV and Treg cells in conjunction with CSA was significantly lower as compared to TCONV and Treg cells alone (P = .009) or with RAPA (P = .008) or MMF (P = .02) as shown in Figure 5C.

The observation made with BLI was reproducible in another BMT model (C57B/6→Balb/c) that we previously reported1 and that allowed us to use the congenic Thy-1 markers to distinguish between donor-derived TCONV versus Treg cells for CFSE-based proliferation analysis. These studies demonstrated reduced Treg expansion in animals receiving CSA (Figure 6A). To obtain a more detailed understanding of the in vivo effect of CSA on FoxP3+ expression at a single-cell level, we quantified FoxP3+ cells within the sorted Thy-1.1+CD4+CD25+ cell population by immunofluorescence. In contrast to RAPA and MMF, CSA-treated mice displayed significantly decreased numbers of FoxP3+ cells within the transferred CD4+CD25+ cell population (Figure 6B). The decreased FoxP3+ Treg/TCONV ratio in the presence of CSA (Table 1) supports the conclusion that FoxP3+ expression and survival of Treg cells within the CD4+CD25+ cell population may require intact early IL-2 signaling, which is altered by CSA.

CSA administration is associated with reduced numbers of CD4+FoxP3+cells and has only minor impact on the expansion of donor-derived CD4+CD25+cells. Expansion of luc+ donor Treg cells in Balb/c mice (H-2kd) receiving TCONV and Treg cells (both H-2kq) alone or TCONV and Treg cells along with CSA (10 mg/kg), RAPA (0.5 mg/kg), or MMF (90 mg/kg) as shown for representative animals on day 7 after BMT (A) and as quantified by emitted photons over total body area at serial time points after BMT (B). (A) Expansion of luc+ Treg (first column from left) is slightly reduced by conjunction of CSA (second column from left) and to a lesser extent by MMF (first column from right). Addition of RAPA (third column from left) has no impact on Treg expansion. (B) TCD-BM (*, n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells (□,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and CSA (▵,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (□, n = 10), or with TCONV and Treg cells and MMF (○, n = 10). Signal intensity is decreased in animals receiving TCONV and Treg cells and CSA or MMF as compared to RAPA (▵ versus □, and ○ versus □, NS). (C) Splenic CD4 donor T cells (H-2kq) were investigated for FoxP3 expression in Balb/c recipients on day 7 after BMT, having received TCONV and Treg cells alone (first column from left) in conjunction with CSA (second column from left), RAPA (third column from left), or MMF (fourth column from left). The percentage of FoxP3+ Treg cells is significantly reduced in the presence of CSA as compared to PBS injection (P = .005) or RAPA (P = .004).

CSA administration is associated with reduced numbers of CD4+FoxP3+cells and has only minor impact on the expansion of donor-derived CD4+CD25+cells. Expansion of luc+ donor Treg cells in Balb/c mice (H-2kd) receiving TCONV and Treg cells (both H-2kq) alone or TCONV and Treg cells along with CSA (10 mg/kg), RAPA (0.5 mg/kg), or MMF (90 mg/kg) as shown for representative animals on day 7 after BMT (A) and as quantified by emitted photons over total body area at serial time points after BMT (B). (A) Expansion of luc+ Treg (first column from left) is slightly reduced by conjunction of CSA (second column from left) and to a lesser extent by MMF (first column from right). Addition of RAPA (third column from left) has no impact on Treg expansion. (B) TCD-BM (*, n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells (□,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and CSA (▵,n = 10), with TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (□, n = 10), or with TCONV and Treg cells and MMF (○, n = 10). Signal intensity is decreased in animals receiving TCONV and Treg cells and CSA or MMF as compared to RAPA (▵ versus □, and ○ versus □, NS). (C) Splenic CD4 donor T cells (H-2kq) were investigated for FoxP3 expression in Balb/c recipients on day 7 after BMT, having received TCONV and Treg cells alone (first column from left) in conjunction with CSA (second column from left), RAPA (third column from left), or MMF (fourth column from left). The percentage of FoxP3+ Treg cells is significantly reduced in the presence of CSA as compared to PBS injection (P = .005) or RAPA (P = .004).

The combination of Treg cells with RAPA does not interfere with GVT activity

To investigate whether the Treg plus RAPA combination would cause generalized immunoparalysis or allow for GVT activity, we used A20-luc/yfp-leukemia cells. This cell line has been shown to result in leukemia with primary migration to the bone marrow and secondary infiltration of spleen and other lymphoid organs when injected at the time of BMT.1 Balb/c recipients (H-2kd) were given intravenously 5 × 106 FVB/N TCD-BM cells (H-2kq) and 1 × 105 A20-luc/yfp- leukemia cells (H-2kd) after lethal irradiation with 800 cGy on day 0. When indicated 8 × 105 Treg cells (day 0) with or without RAPA plus 1.6 × 106 CD4+/CD8+ 1:4 T cells (day 2) were given (both H-2kq).

CFSE-based proliferation analysis. (A) In vivo expansion of CFSE-labeled C57B/6 Treg (H-2kb, Thy-1.1) in Balb/c recipients (H-2kd) on day 6 after BMT is depicted. The congenic markers Thy-1.1 and Thy-1.2 were used to distinguish between Treg and TCONV cells, respectively. All Balb/c recipients (H-2kd) were given 5 × 106 C57B6 TCD-BM cells (H-2kb) after lethal irradiation with 800 cGy. Additionally 5 × 105 Treg (day 0) plus 1 × 106 CD4+/CD8+ T cells (day 2) were given (both H-2kb). Histograms show the FACS profile of CFSE+ Treg cells (H-2kbThy1.1). Numbers of events in each cell division (n) are indicated below the respective peak. Percentages of cells having undergone either 0 or 1 cell division are indicated in each histogram. Proliferation of Treg cells (first column from left) is slightly reduced in the presence of CSA (10 mg/kg; second column from left) and to a lesser extent by MMF (90 mg/kg; fourth column from left). Addition of RAPA (0.5 mg/kg; third column from left) has no impact on Treg expansion. Cells are gated on the donor marker H-2kb and the congenic marker Thy 1.1. (B) Intracellular expression of Foxp3 in donor-derived Thy1.1+H-2kb+CD4+CD25high+ T cells derived from Balb/c recipients having received TCONV (Thy-1.2) and Treg (Thy-1.1) cells alone (first column from left) in conjunction with CSA (second column from left), RAPA (third column from left), or MMF (fourth column from left). Cells were sorted, fixed onto glass slides, and analyzed by immunofluorescence. FoxP3 (Alexa 546), red; DNA (DAPI), blue; double positive, purple; magnification × 200. Percentage of FoxP3+ cells within the donor CD4+CD25+ population (average of 3 independent experiments): 95% ± 3% no immunosuppressant, 57% ± 3.2% CSA (second column from left), 94% ± 3.5% RAPA (third column from left), 89% ± 1.7% MMF (fourth column from left).

CFSE-based proliferation analysis. (A) In vivo expansion of CFSE-labeled C57B/6 Treg (H-2kb, Thy-1.1) in Balb/c recipients (H-2kd) on day 6 after BMT is depicted. The congenic markers Thy-1.1 and Thy-1.2 were used to distinguish between Treg and TCONV cells, respectively. All Balb/c recipients (H-2kd) were given 5 × 106 C57B6 TCD-BM cells (H-2kb) after lethal irradiation with 800 cGy. Additionally 5 × 105 Treg (day 0) plus 1 × 106 CD4+/CD8+ T cells (day 2) were given (both H-2kb). Histograms show the FACS profile of CFSE+ Treg cells (H-2kbThy1.1). Numbers of events in each cell division (n) are indicated below the respective peak. Percentages of cells having undergone either 0 or 1 cell division are indicated in each histogram. Proliferation of Treg cells (first column from left) is slightly reduced in the presence of CSA (10 mg/kg; second column from left) and to a lesser extent by MMF (90 mg/kg; fourth column from left). Addition of RAPA (0.5 mg/kg; third column from left) has no impact on Treg expansion. Cells are gated on the donor marker H-2kb and the congenic marker Thy 1.1. (B) Intracellular expression of Foxp3 in donor-derived Thy1.1+H-2kb+CD4+CD25high+ T cells derived from Balb/c recipients having received TCONV (Thy-1.2) and Treg (Thy-1.1) cells alone (first column from left) in conjunction with CSA (second column from left), RAPA (third column from left), or MMF (fourth column from left). Cells were sorted, fixed onto glass slides, and analyzed by immunofluorescence. FoxP3 (Alexa 546), red; DNA (DAPI), blue; double positive, purple; magnification × 200. Percentage of FoxP3+ cells within the donor CD4+CD25+ population (average of 3 independent experiments): 95% ± 3% no immunosuppressant, 57% ± 3.2% CSA (second column from left), 94% ± 3.5% RAPA (third column from left), 89% ± 1.7% MMF (fourth column from left).

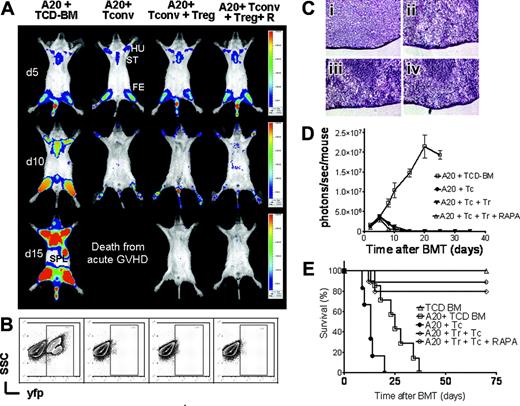

BLI demonstrated tumor-cell infiltration in the bone marrow of the humeri, the femora, and the sternum at day 5 after transplantation in all animals, proving initial engraftment of the A20-luc/yfp-leukemia with a tumor-cell distribution similar to that of the TCD-BM control group (Figure 7A upper row). Tumor progression and additional infiltration of the spleen on day 15 were observed in animals receiving TCD-BM only (Figure 7A first column from the left). Animals that received TCD-BM and TCONV cells achieved tumor control (Figure 7A second column from the left); however, they died even earlier from aGVHD. In contrast, animals receiving TCONV with Treg cells rejected the tumor cells, as determined by loss of tumor signal independent of additional RAPA coinjection, indicating that this combination allows for effector function of cytotoxic T cells against A20 tumor cells. These animals had the best overall survival (Figure 7E).

To confirm that the observed signal loss was indeed associated with tumor clearance, FACS analysis and examination of histologic sections from spleen and bone marrow were performed. FACS analysis of bone marrow cells at day 12 after transplantation indicated a distinct yfp+ cell population in the group that received TCD-BM alone, whereas there was tumor clearance in animals receiving TCONV and TCONV plus Treg cells with or without RAPA (Figure 7B). H&E staining demonstrated a homogeneous spleen infiltration withA20-luc/yfp-leukemia cells on day 12 in TCD-BM animals (Figure 7Ci), whereas there was no evidence for a significant tumor infiltration in the other groups (Figure 7Cii-iv). Tumor growth or rejection was confirmed by the increase or loss of BLI signal intensity over time (Figure 7D). BALB/c mice coinjected with TCD-BM and A20-luc/yfp-leukemia cells died before day 40 from leukemia and animals receiving additionally TCONV cells died before day 22 due to aGVHD (Figure 7E). Addition of RAPA in BM recipients coinjected with A20-luc/yfp-leukemia cells did not lead to improved survival nor reduced signal intensity (data not shown), indicating that RAPA has no significant impact on the A20-luc/yfp tumor growth in contrast to other murine tumor models.27

Discussion

Preclinical studies indicate that it might be possible to promote the generation of Treg cells or enhance their activity by treatment with various drugs, such as MMF28 or RAPA.29 However, studies on MMF combined the drug with 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in a diabetes model.28 Therefore, no direct evidence that the expansion of CD4+CD25+ cells was due to either MMF or 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 was provided. Furthermore, there was no information on the level of FoxP3 expression within this population. Recent in vitro studies showed that RAPA can serve as a tool for murine Treg-cell expansion,30 whereas CSA, but not RAPA, reduces the highly suppressive subpopulation of human CD4+CD25+CD27+ Treg cells.31

GVT effector function of TCONVcells is preserved in the presence of Treg cells and RAPA. Tumor growth and elimination are visualized by bioluminescence imaging (A), FACS analysis (B), histology (C), emitted photons over time (D), and survival (E). All Balb/c recipients (H-2kd) were given 1 × 105 A20 leukemia cells (H-2kd) and BMT was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” (A) luc+A20 tumor-cell localization at 5 days (top row), 10 days (middle row), and 15 days (bottom row) after BMT in representative animals given transplants with TCD-BM alone (first column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV cells (second column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells (third column from left), and TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (fourth column from left). ST indicates sternum; HU, humerus; FE, femur; SPL, spleen. (B) Bone marrow samples with yfp+ A20 cells of recipients on day 12 after transplantation with TCD-BM alone (first column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV cells (second column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells (third column from left), and TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells and rapamycin (fourth column from left). (C) H&E stains of representative spleen samples gathered on day 12 from animals receiving TCD-BM only (Ci), TCD-BM plus TCONV cells (Cii), TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells (Ciii), and TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (Civ). A homogenous leukemic infiltration is found only in animals receiving TCD-BM only (Ci) but not in the other groups. Microscopic evaluation was performed on a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 microscope equipped with 20 ×/0.45 and 40 ×/0.60 objective lenses (Nikon, Melville, NY). Photographs were captured by using a Spot digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Digital images were saved as TIFF files, which were inserted into and processed with PowerPoint software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). (D) Expansion of luc+A20 tumor cell as measured in photons over total body area (photons/second/mouse). Animals rejecting the A20 tumor demonstrate a rapid signal loss within the first 15 days after BMT. (E) Survival of BALB/c mice receiving TCD-BM alone (▵, n = 15), TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells (□, n = 15), TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells plus TCONV cells (•,n = 15), TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells plus TCONV and Treg cells (⋄,n = 12), or TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells plus TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA 0.5 mg/kg; ○,n = 12). Data from 3 independent experiments are combined.

GVT effector function of TCONVcells is preserved in the presence of Treg cells and RAPA. Tumor growth and elimination are visualized by bioluminescence imaging (A), FACS analysis (B), histology (C), emitted photons over time (D), and survival (E). All Balb/c recipients (H-2kd) were given 1 × 105 A20 leukemia cells (H-2kd) and BMT was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” (A) luc+A20 tumor-cell localization at 5 days (top row), 10 days (middle row), and 15 days (bottom row) after BMT in representative animals given transplants with TCD-BM alone (first column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV cells (second column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells (third column from left), and TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (fourth column from left). ST indicates sternum; HU, humerus; FE, femur; SPL, spleen. (B) Bone marrow samples with yfp+ A20 cells of recipients on day 12 after transplantation with TCD-BM alone (first column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV cells (second column from left), TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells (third column from left), and TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells and rapamycin (fourth column from left). (C) H&E stains of representative spleen samples gathered on day 12 from animals receiving TCD-BM only (Ci), TCD-BM plus TCONV cells (Cii), TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells (Ciii), and TCD-BM plus TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA (Civ). A homogenous leukemic infiltration is found only in animals receiving TCD-BM only (Ci) but not in the other groups. Microscopic evaluation was performed on a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 microscope equipped with 20 ×/0.45 and 40 ×/0.60 objective lenses (Nikon, Melville, NY). Photographs were captured by using a Spot digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Digital images were saved as TIFF files, which were inserted into and processed with PowerPoint software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). (D) Expansion of luc+A20 tumor cell as measured in photons over total body area (photons/second/mouse). Animals rejecting the A20 tumor demonstrate a rapid signal loss within the first 15 days after BMT. (E) Survival of BALB/c mice receiving TCD-BM alone (▵, n = 15), TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells (□, n = 15), TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells plus TCONV cells (•,n = 15), TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells plus TCONV and Treg cells (⋄,n = 12), or TCD-BM plus A20 leukemia cells plus TCONV and Treg cells and RAPA 0.5 mg/kg; ○,n = 12). Data from 3 independent experiments are combined.

Our study provides the first evidence that RAPA and MMF rather than CSA preserve murine Treg function and expansion and FoxP3 expression levels when administered after allogeneic BMT. Consistent with findings in human Treg cells,31 we observed that CSA did not abrogate but significantly reduced the function of allostimulated Treg cells in vitro. Reduced FoxP3 gene transcription of murine Treg cells when exposed to CSA, but not to RAPA and MPA, is consistent with a recent study showing that calcineurin inhibitors reduce FoxP3 expression in human Treg cells, whereas mTOR inhibitors have little or no impact.32 Reduced IL-2 levels in the presence of CSA and reversion of the CSA effect by IL-2 addition to the Treg activation culture indicated that IL-2 depletion may be involved in the interference of CSA with Treg function. The critical importance of signaling by IL-2 for Treg activation and suppressive activity has been shown in previous studies.6,7,33 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that RAPA and MPA profoundly affect the phenotype and function of APCs by reducing their antigen-uptake capacity34 and the expression of costimulatory molecules,35 thereby favoring the differentiation of tolerogenic APCs. Thus, suppressor function of Treg cells exposed to RAPA or MPA could be enhanced by an indirect effect of RAPA and MPA on APCs. APC-derived IL-2 has been demonstrated to be critical for the proliferation of allogeneic T cells and was found to be enriched at the APC/T-cell interface during in vitro cognate interaction,36,37 suggesting that IL-2 production by APCs may account for the presence of the cytokine in the primary Treg activation culture that we applied. The observation that Treg cells reisolated from CSA-containing cultures were less suppressive and had reduced levels of FoxP3 expression could be in part due to increasing numbers of TCONV cells within this culture. However, the primarily applied Treg population was highly purified (≥ 96% CD4+CD25+FoxP3+) and we did not detect a significant change in GITR and CTLA-4 expression during the coculture (data not shown), making a massive overgrowth of TCONV cells unlikely.

To further evaluate the relevance of these findings in vivo, we used an established aGVHD model18 in which adoptive transfer of donor-type Treg cells can prevent GVHD lethality. Consistent with the in vitro findings RAPA and to a lesser extent MMF did not interfere with Treg function. The fact that MMF had some effect on Treg cells in vivo may be explained by its impact on lymphocyte proliferation in general and corresponds to the observation that Treg proliferation in vivo was lower as compared to the RAPA group. The observation that CSA interfered with Treg-related protection is in line with reports that CSA but not RAPA can antagonize the induction of tolerance.38-41 This finding has been so far explained by the interference of CSA with activation-induced cell death of effector T cells, which is not seen when the mTOR signaling pathway is blocked with RAPA.42 By showing the reduced number of FoxP3+ Treg cells in vivo when exposed to CSA, our data provide an additional explanation for these findings. The observation that in vivo exposure to CSA but not to RAPA and MMF reduced the level of intracellular expression of FoxP3, which is critical for Treg function,43,44 is consistent with our in vitro data and indicates that blockade of calcineurin-dependent IL-2 production prevents Treg-mediated tolerance. The fact that reduced expansion of Treg cells in the presence of CSA was not statistically significant is consistent with our in vitro data, where equal numbers of Treg cells were reisolated following CSA exposure, indicating that reduced expansion of Treg cells cannot alone account for the impaired suppressor function of Treg cells in the presence of CSA in vivo. Furthermore, our in vivo findings with impaired IL-2 gene transcription in the presence of CSA are consistent with studies in mice deficient for IL-2 or the α-subunit of the IL-2 receptor.10,11 A possible method to overcome the detrimental effect of CSA-dependent depletion of IL-2 while conserving its beneficial immunosuppressant effect may be the coadministration of IL-2.

Consistent with the concept of Treg-cell-mediated tolerance, depletion of Treg cells in mice with tumors improves immunemediated tumor clearance45 and enhances the response to immunebased therapy.46 In light of these data our observation that CSA has a significant impact on Treg function in vivo may be relevant in the attempt to break Treg-mediated tolerance to tumor-associated antigens in humans with cancer and increased numbers of peripheral47 or intratumoral48 Treg cells.

The observation that the Treg/RAPA combination demonstrated a sustained suppression of proliferation of TCONV cells could be potentially unfavorable in allogeneic transplantation attempting to exploit the GVT effect of donor T cells. Our results, however, show that the Treg/RAPA combination did not cause generalized immune paralysis because it did not interfere with bone marrow engraftment and did not abrogate the ability of alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ TCONV cells to eradicate an established tumor. Previous studies have demonstrated that Treg cells reduce expansion of alloreactive T cells after BMT but not their activation, which is critical for tumor clearance.1

We conclude that the RAPA/Treg combination was most favorable with respect to GVHD-related morbidity and mortality. Reduced suppressor function of CSA-exposed Treg cells was IL-2 dependent and correlated with a decreased number of FoxP3+ T cells both in vitro and in vivo. Beside adequate GVHD control, the combination of Treg cells with RAPA allowed for GVT activity, suggesting a novel scientifically justified immunosuppressive combination of RAPA and MMF, which will be studied in the clinic. Conversely, the inhibitory effects by CSA on Treg function may have important implications for boosting immune responses to vaccination protocols.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 7, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0329.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; RO1 CA0800065 and P01 HL075462). R.Z. is supported by the Dr Mildred-Scheel-Stiftung, Germany. V.N. is supported by 5 K08 AI060888 from the NIH. A.B. is supported by a Supergen Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Amy Strelzer-Manasevit Research Program (NMDP).

R.Z. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; V.H.N. performed research and analyzed data; A.B. contributed new reagents, performed research, and analyzed data; M.B., S.S., and J.B. performed research and analyzed data; C.H.C. designed research and contributed vital new reagents and analytic tools; and R.S.N. designed research and helped to write the paper.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

The authors are grateful to Ruby M. Wong for expert assistance with statistical analysis; to Janelle Olson, Lena Ho, and Jing-Zhou Hou for helpful discussion; and to Mobin Karimi for excellent technical support.