Abstract

The IgA Fc receptor (FcαRI) has dual proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions that are transmitted through the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of the associated FcRγ subunit. Whereas the involvement of FcαRI in inflammation is well documented, little is known of its anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Here we show that monomeric targeting of FcαRI by anti-FcαRI Fab or serum IgA triggers apoptosis in human monocytes, monocytic cell lines, and FcαRI+ transfectants. However, the physiologic ligand IgA induced apoptosis only when cells were cultured in low serum conditions, indicating differences with induction of anti-inflammatory signaling. Apoptosis signaling required the FcRγ ITAM, as cells transfected with FcαRI or with a chimeric FcαRI-FcRγ responded to death-activating signals, whereas cells expressing a mutated FcαRIR209L unable to associate with FcRγ, or an ITAM-mutated chimeric FcαRI-FcRγ, did not respond. FcαRI-mediated apoptosis signals were blocked by treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk, involved proteolysis of procaspase-3, and correlated negatively with SHP-1 concentration. Anti-FcαRI Fab treatment of nude mice injected subcutaneously with FcαRI+ mast-cell transfectants prevented tumor development and halted the growth of established tumors. These findings demonstrate that, on monomeric targeting, FcαRI functions as an FcRγ ITAM-dependent apoptotic module that may be fundamental for controlling inflammation and tumor growth.

Introduction

The receptor specific for the IgA Fc region (FcαRI or CD89) is expressed on blood myeloid cells, including monocyte/macrophages, dendritic cells, Kupffer cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils.1 It transmits IgA-mediated effector functions via an IgA-binding module (Ka about 106 M−1) that can be expressed with or without physical association with the disulfide-linked signaling adaptor FcRγ.2,3 The FcRγ-associated receptor has signaling functions that involve an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), consisting of a conserved sequence that is present in the cytoplasmic domain of FcRγ and is shared by different signaling subunits associated with receptors such as TCR and BCR and other FcRs. Although the ITAM was initially reported to mediate activating responses, recent data suggest that, in certain conditions, this motif can also trigger inhibitory responses mediated by a variety of receptors.4-6 The latter include FcαRI, a dual-function receptor that can mediate both activating and inhibitory responses depending on the type of interaction with its ligand. Sustained multimeric aggregation mediates activation of target-cell functions, such as superoxide production, cytokine release, and antigen presentation.7-9 Monomeric targeting with IgA or with a variety of anti-FcαRI (A77, A59, or A62, but not A3) Fab fragments triggers an inhibitory response to heterologous immunoreceptors such as FcϵRI and FcγR.5 Like the activating functions, the inhibitory cross-talk is dependent on the FcRγ ITAM. However, in contrast to receptors bearing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM), such as FcRγIIB,10 the inhibitory signal does not require coaggregation. Monomeric targeting of FcαRI also has powerful anti-inflammatory activity in vivo because administration of anti-FcαRI Fab suppresses manifestations of allergic asthma in FcαRI transgenic mice.5

Activation of certain FcRs also promotes cell death. Thus, FcγRIIB expressed on B cells not only terminates the activation signals of coengaged receptors, via an ITIM-dependent mechanism, but, in case of isolated aggregation, is also able to trigger an apoptotic response.11 The latter involves ITIM and Src homology 2 domain–containing inositide phosphatase (SHIP)–independent and c-abl-family kinase-dependent pathways.12-14 Recruitment of the Src homology 2 domain-containing phosphatase (SHP)–1 to the B- and T-cell antigen receptors (BCR and TCR) was also shown to negatively correlate with the induction of apoptosis.12,15 Indeed, SHP-1–deficient mice are unusually susceptible to clonal deletion of their B- and T-cell compartment.15-17 Although the precise mechanisms whereby SHP-1 negatively regulates apoptosis remains unknown, a possible hypothesis is that SHP-1 raises the threshold required for antigen receptor signaling spread thereby linking it to other biologic outcomes such as cell death.

Incubation of neutrophils with immobilized IgA or secretory IgA also induces apopotosis.18 This likely involves FcαRI, the only IgA receptor so far detected on neutrophils. Previous reports also suggest that ITAMs are essential for transmitting growth-arrest and apoptotic signals, and these functions of ITAMs are positively regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation.19 Because we have previously shown that monomeric targeting of FcαRI can induce cellular signaling, we investigated whether such signaling might generate death-activating signals. We found that monomeric occupancy of FcαRI by anti-FcαRI Fab or IgA directly induced apoptosis on monocytes and monocytic cell lines. This required the FcαRI-associated FcRγ subunit and the ITAM, but, contrary to inhibitory signaling, was also induced by A3 Fab. Apoptosis induction by the natural ligand, IgA, required an additional signal, because it was observed only in low serum conditions. Finally, FcαRI targeting in vivo prevented tumor development and growth, with possible implications for cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Animals

Nude mice were purchased from Janvier (Le Genest-St-Isle, France). Mice were bred and maintained at the mouse facilities of IFR02 at Bichat Medical School. Transgenic mice expressing human FcαRI (CD89, line 83) were back-crossed for more than 12 generations with C57BL/6 mice.20 All experiments were done in accordance with national ethical guidelines and were approved by a local committee (animal facility of IFR02 of the University of Paris 7; authorizations A75-18-01 and 7413).

Immunoglobulins and antibodies

The mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) A3, A59, A62, and A77 specific for FcαRI, and an irrelevant IgG1κ control mAb (clones 320.1)21 were used as either F(ab′)2 or Fab fragments.22 Rabbit anti–mouse IgG antibody (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL) was used as F(ab′)2. F(ab′)2 fragments were obtained by pepsin digestion as described.23 Fab were prepared by pepsin digestion followed by reduction with 0.01 M cysteine and alkylation with 0.15 M iodoacetamide at pH 7.5. Complete digestion and purity were controlled by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining. The anti–caspase-3 antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The antiscramblase antibody has been described previously.5 Purified serum IgA (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), IgG (Southern Biotechnology), goat anti–human IgA (Southern Biotechnology) and rabbit anti-SHP1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, La Jolla, CA) were also used.

Cell culture and stimulation

Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from whole blood by Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) gradient centrifugation. Enriched monocyte populations (60%-80% pure) were obtained by subjecting MNCs to plastic adherence as described24 and were cultured in either 24- or 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL of RPMI-Glutamax medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) before use. RBL-2H3 cells expressing wild-type (WT) human FcαRI, mutant FcαRIR209L, chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ, or chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ mutated in the FcRγITAM (Y268/Y278F) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, and 1 mg/mL G418 (Invitrogen) as described.5 Cells were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended in fresh media in 24-well plates at a density of 106/mL for 24 hours before use. Mouse peritoneal macrophages were obtained following thioglycollate broth (4 days) before cell harvest as described.25 The cells were then either plated on glass coverslips or kept in suspension in polypropylene tubes on ice. Purity was greater than 98%, as determined by CD11b staining.

Measurement of apoptosis by annexin V and PI staining

Apoptotic cells were identified by staining with annexin V and propidium iodide (PI).26 Briefly, cells (106) were treated with apoptosis-inducing agents for the times indicated, then washed and suspended in a binding solution (10 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) containing annexin V–biotin, at the dilutions recommended by the manufacturer (Beckman Coulter, Villepinte, France). After 30 minutes the cells were washed and streptavidin-allophycocyanin (APC; 5 μg/mL) and PI (1 μg/mL) were added for 10 minutes before washing and analysis with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson ImmunoCytometry System, San Jose, CA). At least 10 000 cells were analyzed per sample. Early apoptosis and late apoptosis, respectively, were determined as the percentages of annexin V+/PI− and annexin V+/PI+ cells.

Measurement of apoptosis by counting apoptotic nuclei with hypoploid DNA

The proportion of cells with hypoploid DNA was measured by using a modification of the Nicoletti method.27 Briefly, cells (106) were incubated at 37°C with anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or an irrelevant control (320) Fab. The medium was removed and cells were fixed in 70% ethanol at −20°C for at least 30 minutes. After ethanol removal, phosphate buffer consisting of 0.2 M Na2HPO4, 0.1 M citric acid (pH 7.8) was added for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were centrifuged and stained for 30 minutes at room temperature with 1 mL PI staining buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 10 μg/mL RNAse A, and 10 μg/mL PI in PBS) before analysis by flow cytometry. Apoptotic nuclei containing degraded hypoploid DNA (lower fluorescence intensity) were easily distinguished from nonapoptotic nuclei (sharp peaks), and their percentage was determined.

Counting of apoptotic cells by DAPI staining

DAPI staining was performed as previously described.28 Briefly, cells were incubated at 37°C with anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or an irrelevant control (320) Fab. The medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed by incubation with 70% ethanol for 30 minutes. Following washing in PBS, cells were incubated in 1 μg/mL DAPI solution for 30 minutes in the dark. Apoptotic cells appear as cells with highly condensed fluorescent nuclei. Fluorescent cells were counted with a Nikon TE2000-U microscope coupled to a DXM1200F camera (Nikon, Champigny sur Marne, France), using a 1× auxiliary lens and a direct 1× C-mount. Objective magnifications are indicated.

Measurement of mitochondrial apoptosis by staining with DiOC6

Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) were assessed by measuring uptake of the lipophilic cationic dye 3,3-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC

Measurement of caspase-3 activation

After induction of apoptosis, cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.3% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4, 30 mM Na4P2O7, 50 U/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin), and then postnuclear supernatants were prepared. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking in 4% BSA, membranes were incubated with anticaspase mAb for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by goat anti–mouse immunoglobulin coupled to HRP (Ig-HRP). After decapping, membranes were reprobed with antiscramblase antibody followed by goat anti–mouse Ig-HRP. Filters were developed by enhanced chemoluminescence (ECL; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Study of the effect of caspase inhibition by zVAD-fmk

Cells (106/mL) were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with 20 μM pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk (N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The test agents were added and incubation was continued for the times indicated at 37°C before apoptosis assay.

SHP-1 knock-down experiments using siRNA

Rat SHP-1 in RBL cells was targeted with a cocktail of 3 siRNAs (Eurogentec, Louvain, Belgium): siRNA1 (sense strand) CAGGCACCAUCAUUGUCAU; siRNA2: GAACCGCUACAAGAACAUU; siRNA3: CAGAGCUGGUGGAGUACUA. A universal scramble negative siRNA GCCCCGUCUACAUACAUGU was used as a control. FcαRIR209L/γ RBL cells were transfected with siRNA by 2 successive electroporations 24 hours apart. For each transfection, cell density was adjusted to 1 × 107/mL in electropermeabilization buffer (120 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0) before electroporation with annealed siRNAs (0.05 μM) using an Easyject electroporation apparatus (Eurogentec) at 250 V and 2100 μF. Between transfections, floating dead cells were discarded. Two successive transfections were preferred over a single one to improve the effective knock-down of SHP-1. After each electroporation, cells were cultured in complete medium. After the second electroporation, apoptosis experiments were started by incubating cells with anti-FcαRI (A77) or control antibody (320). The effectiveness of siRNA treatment was tested by SHP-1 immunoblotting of extracts of untreated cells grown in parallel.

Skin grafting of FcαRI RBL transfectants and treatment protocols

Adherent FcαRI RBL transfectants grown as monolayers were detached by trypsinization, washed once with complete medium and once with serum-free DMEM, and were then resuspended in the same medium. Chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ transfectants (1 × 107) were injected subcutaneously into 6-week-old female nude mice to induce the development of subcutaneous tumors.31 Preventive and curative treatments were tested. In the former, 50 μg A77 or 320 control Fab was injected subcutaneously, starting on day 0, as indicated in the legends; curative treatment was started on day 12, as indicated in the figure legends. Four groups of 6 mice were used. Mortality and tumor size were recorded.

Detection of apoptotic cells by TUNEL

Tumors were fixed in 20% formalin and embedded in paraffin or immediately frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Zoeterwoude, the Netherlands) for immunohistochemical analysis. Formalin-fixed sections 5 μm thick were analyzed after PAS staining. Apoptotic cells were detected on 5-μm cross-sections by the TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) method implemented with the in situ apoptosis detection kit (Chemicon, Temeculo, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Results

Monomeric targeting of FcαRI with anti-FcαRI Fab in human monocytes and FcαRI transfectants induces apoptosis

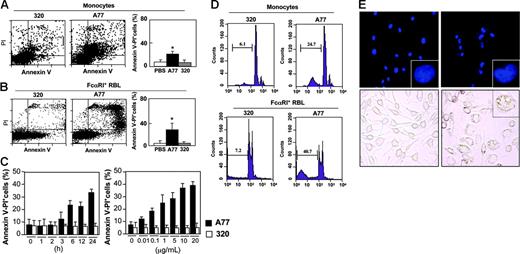

Because monomeric targeting of FcαRI transmits inhibitory signals,5 we examined whether, like FcγIIB,11 it could also promote apoptosis. Monocytes isolated from human blood and treated with irrelevant 320 Fab showed a background level of apoptosis similar to that of solvent (PBS)–treated cells (Figure 1A, left and right panels). Treatment with A77 anti-FcαRI Fab, however, caused a shift to an annexin V/PI+ population within 24 hours, indicating apoptosis induction in a significant fraction of cells (Figure 1A, middle and right panels). Similar data were obtained with peritoneal macrophages from FcαRI humanized transgenic mice (not shown).

Induction of apoptosis by FcαRI targeting in human monocytes and FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants. (A-B) Analysis of annexin V/PI double-positive populations in human blood monocytes (A) and RBL-2H3 cells expressing WT FcαRI (B) after 24 hours of treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. Cells were stained with annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” The mean ± SD percentage of annexin V/PI double-positive cells treated with PBS, 320, or A77 Fab in 5 experiments is shown. *P < .05. (C) Kinetic and dose-response analysis of annexin V/PI double-positive populations of WT FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants after treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab for 1 to 24 hours or for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations of A77 or 320 Fab. The percentage of annexin V/PI double-positive populations was determined as described in panel A. (D) Analysis of hypoploid nuclei in blood monocytes and WT FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants after treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) or control (320) Fab for 24 hours. Cells were stained with PI and analyzed for the appearance of hypoploid nuclei as described in “Materials and methods.” Numbers indicate the percentage of cells with hypoploid nuclei (a sign of apoptosis). (E) Analysis of condensed apoptotic nuclei in WT FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants after 24 hours of treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. Following treatment, cells were stained with DAPI as described in “Materials and methods,” before analysis by fluorescence microscopy (top panels; 40×/1.3 NA objective lens; insets represent a zoom of one of the nuclei.). Apoptotic cells have condensed nuclei and crescent shape (inset). Treated cells were also examined by light microscopy (lower panels, 40×/1.3 NA objective lens). Apoptotic cells contained large vacuoles (inset).

Induction of apoptosis by FcαRI targeting in human monocytes and FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants. (A-B) Analysis of annexin V/PI double-positive populations in human blood monocytes (A) and RBL-2H3 cells expressing WT FcαRI (B) after 24 hours of treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. Cells were stained with annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” The mean ± SD percentage of annexin V/PI double-positive cells treated with PBS, 320, or A77 Fab in 5 experiments is shown. *P < .05. (C) Kinetic and dose-response analysis of annexin V/PI double-positive populations of WT FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants after treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab for 1 to 24 hours or for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations of A77 or 320 Fab. The percentage of annexin V/PI double-positive populations was determined as described in panel A. (D) Analysis of hypoploid nuclei in blood monocytes and WT FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants after treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) or control (320) Fab for 24 hours. Cells were stained with PI and analyzed for the appearance of hypoploid nuclei as described in “Materials and methods.” Numbers indicate the percentage of cells with hypoploid nuclei (a sign of apoptosis). (E) Analysis of condensed apoptotic nuclei in WT FcαRI RBL-2H3 transfectants after 24 hours of treatment with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. Following treatment, cells were stained with DAPI as described in “Materials and methods,” before analysis by fluorescence microscopy (top panels; 40×/1.3 NA objective lens; insets represent a zoom of one of the nuclei.). Apoptotic cells have condensed nuclei and crescent shape (inset). Treated cells were also examined by light microscopy (lower panels, 40×/1.3 NA objective lens). Apoptotic cells contained large vacuoles (inset).

To study FcαRI-mediated apoptosis, we took advantage of previously established rat RBL mast-cell transfectants expressing WT human FcαRI that are able to associate with endogenous rat FcRγ.3 As shown in Figure 1B, monomeric targeting of FcαRI with A77 Fab in these transfectants induced apoptosis (between 30% and 40% of cells). Kinetic analysis showed that double-positive (annexin V/PI) cells could be detected as early as 3 hours and that their numbers were maximal after 24 hours (Figure 1C, left panel). When annexin V single staining was used to detect early signs of apoptosis, a positive population was seen after only 1 hour (not shown). Dose-response studies at 24 hours revealed that apoptosis was induced at Fab concentrations as low as 0.01 μg/mL and was maximum between 5 and 10 μg/mL (Figure 1C, right panel). Apoptosis was also confirmed by determining the appearance of cells with hypoploid nuclei. An increased proportion was seen in A77-treated cells both in blood monocytes and FcαRI+ transfectants as compared to 320 Fab-treated cells (Figure 1D). Similarly, A77 Fab-treated cells show an increased proportion of cells with highly condensed nuclei as revealed by staining with DAPI and with a highly vacuolated phenotype (Figure 1E). Apoptosis was not induced in non-transfected cells (not shown).

Induction of apoptosis requires the FcRγ ITAM

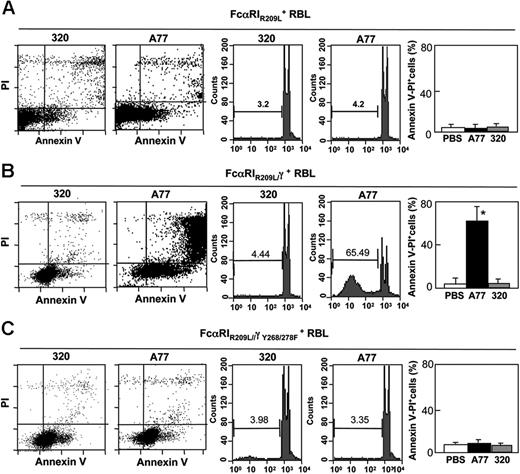

To determine which type of FcαRI—associated or not associated with FcRγ3 —accounts for the apoptotic response, we compared cells transfected with WT FcαRI to cells transfected with a transmembrane mutant receptor (FcαRIR209L) unable to associate with the FcRγ signaling adaptor. This transfectant expressed similar levels of receptor as WT FcαRI transfected cells5 (and not shown). Cells were treated for 24 hours with A77 or control 320 Fab and were then examined for signs of cell death by annexin V and PI staining (Figure 2A, left panel). Only a very small population (∼3%) of double-positive cells was detected among cells transfected with the mutant receptor FcαRIR209L and among 320 Fab-treated cells. Similar data were obtained by counting apoptotic nuclei (Figure 2A, right panel).

FcαRI-induced apoptosis is mediated by FcRγ ITAM. Induction of apoptosis in RBL-2H3 cells transfected with transmembrane mutated FcαIRR209L (A), chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ (B), or chimeric ITAM-mutated FcαRIR209L/γY268/278F (C). Cells were treated with 10 μg/mL A77 or irrelevant control (320) Fab for 24 hours before annexin V/PI staining (left panel) or analysis of hypoploid nuclei (middle panel) as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage of apoptotic (annexin V/PI double-positive) cells is shown (right panel). Values are the percentages of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01.

FcαRI-induced apoptosis is mediated by FcRγ ITAM. Induction of apoptosis in RBL-2H3 cells transfected with transmembrane mutated FcαIRR209L (A), chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ (B), or chimeric ITAM-mutated FcαRIR209L/γY268/278F (C). Cells were treated with 10 μg/mL A77 or irrelevant control (320) Fab for 24 hours before annexin V/PI staining (left panel) or analysis of hypoploid nuclei (middle panel) as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage of apoptotic (annexin V/PI double-positive) cells is shown (right panel). Values are the percentages of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01.

These results suggested an important role of FcRγ in the death-activating signal generated through FcαRI. A transfectant bearing a chimeric receptor, FcαRIR209L/γ, in which the intracellular portion of FcαRIR209L was replaced by FcRγ, was thus tested for its capacity to mediate apoptosis after targeting with A77 Fab. As shown in Figure 2B (left panel), the addition of the intracytoplasmic portion of FcRγ to the mutant receptor restored the capacity of FcαRIR209L to induce apoptosis after monomeric targeting of A77 Fab-treated but not 320 Fab-treated cells. The proportion of annexin V/PI double-positive cells was higher among FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants (∼60%) than among control 320 Fab-treated cells (8.2%). This was confirmed by counting hypoploid apoptotic nuclei (Figure 2B, right panel). The role of FcRγ ITAM in the inhibitory effect was then examined. RBL cells transfected with a chimeric receptor, FcαRIR209L-γ, in which 2 Y-to-F point mutations are introduced in the ITAM, were tested for apoptosis following treatment with A77 Fab. As shown in Figure 2C (left panel), no apoptosis was seen in these mutant transfectants, indicating the importance of the FcRγ ITAM in this mechanism. This observation was confirmed by cell-cycle analysis (Figure 2C, right panel).

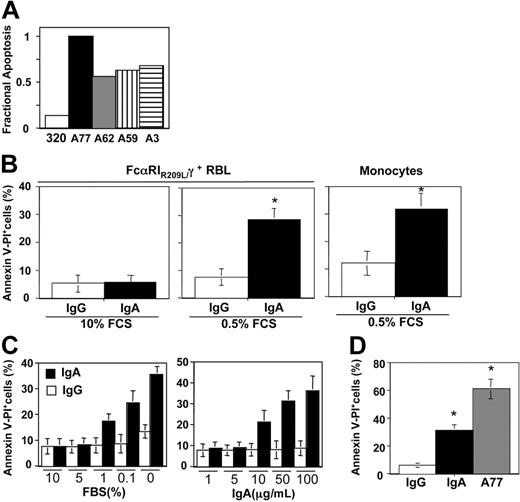

Apoptosis signaling by FcαRI differs from inhibitory signaling

Previous studies have shown that Fab fragments A59, A62, and A77 derived from anti-FcαRI mAbs can induce inhibitory signaling, whereas fragment A3 cannot.5 We therefore examined the capacity of these fragments to trigger an apoptotic response. As shown in Figure 3A, the apoptotic response was induced by all 4 Fabs, including A3. We also tested the effect of the physiologic ligand, IgA. As shown in Figure 3B (left panel), as for control IgG, no apoptosis was observed after incubation with monomeric IgA, even at high concentrations, thus contrasting with data that have shown powerful anti-inflammatory properties of IgA.5,32 However, incubation with IgA at low serum concentrations (0.5%) resulted in an apoptotic response in transfectants and monocytes, contrary to IgG (Figure 3B right panel), indicating that IgA requires additional signals to induce apoptosis. As shown in Figure 3C, susceptibility to apoptosis induction by IgA began at a serum concentration of 1% and was maximal in the complete absence of serum. The required IgA concentrations were relatively high, with a maximal effect at about 100 μg/mL. In the absence of serum, incubation with A77 induced a much higher level of apoptosis (Figure 3D).

Induction of apoptosis in FcαRI RBL transfectants and blood monocytes by purified human IgA. (A) Comparison of apoptosis induction in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants treated with different anti-FcαRI Fab fragments. Cells were incubated for 24 hours with 10 μg/mL A77, A62, A59, A3, or control (320) Fab fragments and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by analysis of the annexin V/PI double-positive population. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Induction of apoptosis in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants and blood monocytes by IgA was measured in the presence of 10% or 0.5% serum. Cells were treated with 50 μg/mL human IgA or control human IgG for 10 hours before annexin V/PI staining. Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (C) Comparison of apoptosis induction in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants after incubation with 50 μg/mL IgA and 10 μg/mL A77 Fab in the presence of 0.5% serum. After 10 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. (D) Analysis of apoptosis in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants after treatment with 50 μg/mL human IgA (□) or control IgG (▪) in the presence of various percentages of serum (left panel) and after treatment with various concentrations of immunoglobulin in the presence of 0.5% serum (right panel). After 10 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01.

Induction of apoptosis in FcαRI RBL transfectants and blood monocytes by purified human IgA. (A) Comparison of apoptosis induction in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants treated with different anti-FcαRI Fab fragments. Cells were incubated for 24 hours with 10 μg/mL A77, A62, A59, A3, or control (320) Fab fragments and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by analysis of the annexin V/PI double-positive population. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Induction of apoptosis in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants and blood monocytes by IgA was measured in the presence of 10% or 0.5% serum. Cells were treated with 50 μg/mL human IgA or control human IgG for 10 hours before annexin V/PI staining. Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (C) Comparison of apoptosis induction in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants after incubation with 50 μg/mL IgA and 10 μg/mL A77 Fab in the presence of 0.5% serum. After 10 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. (D) Analysis of apoptosis in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants after treatment with 50 μg/mL human IgA (□) or control IgG (▪) in the presence of various percentages of serum (left panel) and after treatment with various concentrations of immunoglobulin in the presence of 0.5% serum (right panel). After 10 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01.

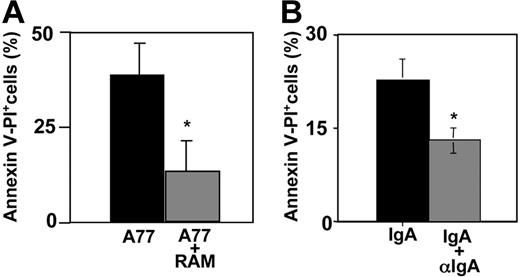

We then examined whether multimeric cross-linking could also induce death-activating signals. We compared cells incubated with A77 Fab and cells incubated with preformed immune complexes of A77 Fab plus rabbit anti–mouse IgG F(ab′)2. As shown in Figure 4A, both types of interaction induced an apoptotic response in FcαRI-transfected RBL cells, but the response was much stronger (∼80%) after monomeric targeting than after multimeric cross-linking. No apoptosis was induced by control 320 Fab or RAM (not shown) alone. We also tested the effect of IgA cross-linking by anti-IgA in serum-free medium. As shown in Figure 4B, whereas monomeric IgA induced apoptosis of about 20% to 25% of FcαRI-transfected RBL cells (as before), multimeric cross-linking of IgA induced a much lower level of apoptosis.

FcαRI monovalent targeting induces apoptosis more strongly than multimeric targeting. (A) FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were incubated with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or preformed complexes of anti-FcαRI (A77) F(ab′)2 and F(ab′)2 rabbit anti–mouse IgG. After 24 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (B) FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were incubated with 50 μg/mL IgA or preformed complexes of 50 μg/mL IgA and 100 μg/mL goat anti–human IgA. After 10 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positive population as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01.

FcαRI monovalent targeting induces apoptosis more strongly than multimeric targeting. (A) FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were incubated with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or preformed complexes of anti-FcαRI (A77) F(ab′)2 and F(ab′)2 rabbit anti–mouse IgG. After 24 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (B) FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were incubated with 50 μg/mL IgA or preformed complexes of 50 μg/mL IgA and 100 μg/mL goat anti–human IgA. After 10 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positive population as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01.

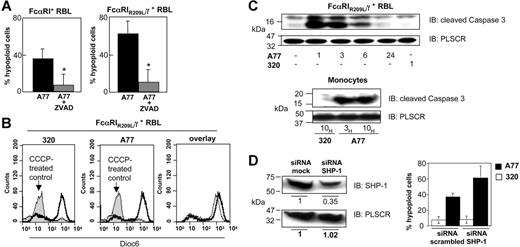

FcαRI death signals involve caspase activation and are blocked by SHP-1

Caspase activation is an early step in cell death and is one of the mature intracellular signaling pathways that promotes apoptosis.33 To investigate whether FcαRI-mediated death-activating signals involve caspase activation, we evaluated apoptosis induction in the presence of zVAD-fmk, a general caspase inhibitor. Chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ and WT FcαRI RBL transfectants were incubated with 20 μM zVAD-fmk for 2 hours before treatment with A77 or 320 Fab. After 24 hours the cells were stained with annexin V/PI and examined for numbers of cells with hypoploid apoptotic nuclei. As shown in Figure 5A, pretreatment with 20 μM zVAD-fmk strongly reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells elicited by treatment with 10 μg/mL Fab A77 in WT FcαRI (left panel) and in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ (right panel) transfectants. In contrast, A77 Fab had no effect on DiOC6 staining, which reveals changes in mitochondrial membrane potential. Control experiments using CCCP, an inducer of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, markedly modified the mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 5B). To directly evaluate the caspase activation status, we measured the cleavage of the proform of caspase-3. As shown in Figure 5C, monomeric targeting of chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ transfectants and monocytes with A77 Fab rapidly led to the appearance of the 17-kDa cleaved (active) form of caspase-3. This was also confirmed by intracellular immunostaining using anti–cleaved caspase-3 antibody analyzed by flow cytometry (not shown). The appearance of cleaved caspase-3 suggested that apoptosis was directly induced by FcαRI signaling. Because the inhibitory function of FcαRI depends on SHP-1 recruitment,5 we examined whether the FcαRI-mediated apoptotic signal was also dependent on this phosphatase by using an siRNA approach to knock down the expression of SHP-1. As shown in Figure 5D (left panel), transfection with SHP-1–specific siRNAs strongly reduced (> 60%) the expression of SHP-1 in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ transfectants. In the corresponding experiment to determine apoptosis, no differences in the background levels (in the presence of 320 Fab) were found between cells transfected with a scrambled siRNA control or with the SHP-1–targeting siRNA (Figure 5D, right panel). By contrast, after treatment with A77, the apoptotic effect in chimeric FcαRIR209L/γ transfectants was increased in cells that had been targeted with SHP-1 siRNA compared with those treated with scrambled siRNA (Figure 5D right panel). In 4 independent experiments in which SHP-1 levels fell by more than 60%, the increase in A77-induced apoptosis in SHP-1 siRNA-transfected cells was 1.53 + 0.12-fold (mean ± SD; P < .05) compared with cells transfected with scrambled siRNA. These observations suggested that high levels of SHP-1 inhibited the FcαRI-mediated apoptotic signal.

Analysis of the apoptosis pathways induced by FcαRI targeting. (A) WT FcαRI and FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were treated with 20 μM zVAD-fmk or solvent for 40 minutes before adding 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab. After 24 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (B) Analysis of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were incubated with the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway-inducing compound CCCP (200 μM) or with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. After 24 hours cells were stained with the mitochondrial membrane potential–sensitive dye DiOC6 and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” Induction of the mitochondrial pathway resulted in a strong loss of DiOC6 staining. (C) Analysis of the “cleaved” (activated) form of caspase-3. FcαRIR209L/γ cells were treated with 10 μg/mL A77 or control (320) Fab for the times indicated. Cells were then lysed, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes before immunoblotting with an antibody recognizing the cleaved form of caspase-3. To control for equal loading, blots were stripped and reprobed with antiscramblase (PLSCR) antibody plus goat anti–rabbit Ig-HRP. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. (D) Effect of SHP-1 siRNA treatment on FcαRI-mediated apoptosis in FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants. Analysis of relative SHP-1 expression levels by anti–SHP-1 immunoblotting in lysates from cells transfected with scrambled or SHP-1–specific siRNA (left panel). Analysis of the percentage of FcαRI-mediated apoptosis in FcαRIR209L/γ cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or SHP-1–targeting specific siRNA (right panel). FcαRIR209L/γ cells were transfected twice, 24 hours apart, with scrambled siRNA or SHP-1–targeting specific siRNA. After the second transfection, cells were treated with 10 μg/mL A77 or irrelevant control (320) Fab (right panel). Cells were then analyzed for hypoploid nuclei as described in “Materials and methods.” Numbers are the percentage of cells with hypoploid nuclei at 18 hours in a representative experiment.

Analysis of the apoptosis pathways induced by FcαRI targeting. (A) WT FcαRI and FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were treated with 20 μM zVAD-fmk or solvent for 40 minutes before adding 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab. After 24 hours cells were analyzed for annexin V/PI double-positivity as described in “Materials and methods.” Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (B) Analysis of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants were incubated with the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway-inducing compound CCCP (200 μM) or with 10 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. After 24 hours cells were stained with the mitochondrial membrane potential–sensitive dye DiOC6 and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” Induction of the mitochondrial pathway resulted in a strong loss of DiOC6 staining. (C) Analysis of the “cleaved” (activated) form of caspase-3. FcαRIR209L/γ cells were treated with 10 μg/mL A77 or control (320) Fab for the times indicated. Cells were then lysed, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes before immunoblotting with an antibody recognizing the cleaved form of caspase-3. To control for equal loading, blots were stripped and reprobed with antiscramblase (PLSCR) antibody plus goat anti–rabbit Ig-HRP. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. (D) Effect of SHP-1 siRNA treatment on FcαRI-mediated apoptosis in FcαRIR209L/γ RBL transfectants. Analysis of relative SHP-1 expression levels by anti–SHP-1 immunoblotting in lysates from cells transfected with scrambled or SHP-1–specific siRNA (left panel). Analysis of the percentage of FcαRI-mediated apoptosis in FcαRIR209L/γ cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or SHP-1–targeting specific siRNA (right panel). FcαRIR209L/γ cells were transfected twice, 24 hours apart, with scrambled siRNA or SHP-1–targeting specific siRNA. After the second transfection, cells were treated with 10 μg/mL A77 or irrelevant control (320) Fab (right panel). Cells were then analyzed for hypoploid nuclei as described in “Materials and methods.” Numbers are the percentage of cells with hypoploid nuclei at 18 hours in a representative experiment.

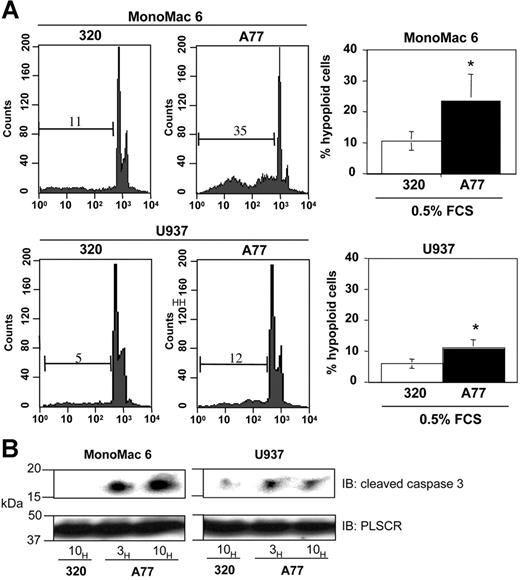

Monomeric targeting of FcαRI with anti-FcαRI Fab induces apoptosis in human monocytic cell lines

To analyze whether monomeric targeting of FcαRI in human tumor cell lines induces apoptosis, we took advantage of human myeloblastic monoMac6 and U937 cells which express FcαRI. As shown in Figure 6A, monomeric targeting of FcαRI with anti-FcαRI A77 Fab in MonoMac6 and U937 cell lines induced apoptosis (between 10% and 35% of cells) as revealed by cell-cycle analysis, whereas no apoptosis was seen with irrelevant 320 Fab. This variability in apoptosis induction was linked to the level of FcαRI expression, as the highest induction of apoptosis was observed in MonoMac6 cells, which express high levels of FcαRI protein than U937 cells (not shown). We also tested the effect of the physiologic ligand, IgA. Incubation with IgA, but not IgG, at low serum concentrations of FCS (0.5%) resulted in an apoptotic response in these cell lines (not shown). To directly evaluate the caspase activation status, we examined the cleavage of the proform of caspase-3 in these cell lines. As shown in Figure 6B, monomeric targeting with A77 Fab rapidly led to the appearance of the 17-kDa cleaved (active) form of caspase-3.

Induction of apoptosis by FcαRI targeting in human monocytic cell lines. (A) Induction of apoptosis in MonoMac6 or U937 cells after 24 hours of treatment with 20 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. Cells were stained with PI and analyzed for the appearance of hypoploid nuclei as described in “Materials and methods.” Numbers indicate the percentage of cells with hypoploid nuclei. Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (B) Analysis of the “cleaved” (activated) form of caspase-3 following anti-FcαRI Fab treatment. The MonoMac6 or U937 cells were treated with 20 μg/mL A77 or control (320) Fab for indicated times. Cells were then lysed, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes before immunoblotting with an antibody recognizing the cleaved form of caspase-3. To control for equal loading, blots were stripped and reprobed with antiscramblase (PLSCR) antibody plus goat anti–rabbit Ig-HRP. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

Induction of apoptosis by FcαRI targeting in human monocytic cell lines. (A) Induction of apoptosis in MonoMac6 or U937 cells after 24 hours of treatment with 20 μg/mL anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab or control (320) Fab. Cells were stained with PI and analyzed for the appearance of hypoploid nuclei as described in “Materials and methods.” Numbers indicate the percentage of cells with hypoploid nuclei. Values indicate the percentage of double-positive cells and are means ± SD of at least 3 separate experiments performed in duplicate. *P < .01. (B) Analysis of the “cleaved” (activated) form of caspase-3 following anti-FcαRI Fab treatment. The MonoMac6 or U937 cells were treated with 20 μg/mL A77 or control (320) Fab for indicated times. Cells were then lysed, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes before immunoblotting with an antibody recognizing the cleaved form of caspase-3. To control for equal loading, blots were stripped and reprobed with antiscramblase (PLSCR) antibody plus goat anti–rabbit Ig-HRP. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

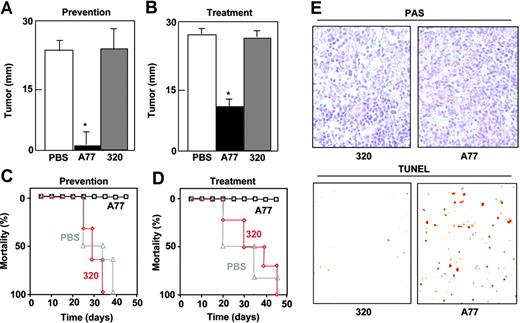

Antitumoral effect of anti-FcαRI Fab treatment of nude mice

The tumoricidal activity of A77 Fab was tested in nude mice injected subcutaneously with chimeric FcαRI RBL transfectants. We used 2 different protocols to measure the effect of A77 Fab. In the first protocol (prevention model), A77 was administered shortly after the injection of tumor cells. As shown in Figure 7A, tumor size was clearly diminished compared with PBS- and 320 Fab-treated mice, and the mice survived significantly longer than controls (Figure 7C). In the second protocol (treatment model), A77 Fab administration was started on day 10, once the subcutaneous tumors had already developed. Tumor development was immediately halted, whereas it continued in mice treated with PBS or 320 Fab (Figure 7B). Again the A77 Fab-treated mice survived significantly longer than controls (Figure 7D). To confirm that the antitumoral effect was due to apoptosis, we applied the TUNEL method to tumor tissue sections from each group. The number of positive cells was far higher in A77 Fab-treated animals than in controls (Figure 7E).

Monovalent targeting of FcRI prevents and arrests subcutaneous tumor development by FcαRI RBL transfectants in nude mice. Nude mice (6/group) were injected subcutaneously with WT FcαRI RBL transfectants. In the prevention model (A,C), animals were treated intraperitoneally with 50 μg anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab, control (320) Fab, or PBS on days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 21. In treatment model (B,D), mice were treated intraperitoneally with 50 μg anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab, control (320) Fab, or PBS on day 12 when tumors had started to develop followed by injections on days, 15, 18, and 21. (A-B) Tumor size was evaluated on day 25 and is represented as the mean ± SD (n = 6). (C-D) Survival of mice treated with PBS, 320 Fab, or A77 Fab. (E) TUNEL analysis of RBL tumor cells after treatment with control (320) Fab or anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab. Images show PAS staining of formalin-fixed tumor sections. Apoptotic cells were visualized by TUNEL analysis of cryosections as described in “Materials and methods (10×/0.30 NA objective lens).

Monovalent targeting of FcRI prevents and arrests subcutaneous tumor development by FcαRI RBL transfectants in nude mice. Nude mice (6/group) were injected subcutaneously with WT FcαRI RBL transfectants. In the prevention model (A,C), animals were treated intraperitoneally with 50 μg anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab, control (320) Fab, or PBS on days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 21. In treatment model (B,D), mice were treated intraperitoneally with 50 μg anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab, control (320) Fab, or PBS on day 12 when tumors had started to develop followed by injections on days, 15, 18, and 21. (A-B) Tumor size was evaluated on day 25 and is represented as the mean ± SD (n = 6). (C-D) Survival of mice treated with PBS, 320 Fab, or A77 Fab. (E) TUNEL analysis of RBL tumor cells after treatment with control (320) Fab or anti-FcαRI (A77) Fab. Images show PAS staining of formalin-fixed tumor sections. Apoptotic cells were visualized by TUNEL analysis of cryosections as described in “Materials and methods (10×/0.30 NA objective lens).

Discussion

We report that monomeric targeting of FcαRI by different anti-FcαRI Fab promotes apoptosis of blood human monocytes, human monocytic cell lines, and RBL mast cells transfected with FcαRI. Apoptosis was not induced in non-transfected RBL cells or in cells transfected with a mutant FcαRIR209L receptor unable to associate with the FcRγ subunit. Expression of a chimeric mutant receptor in which the intracytoplasmic domain was replaced by FcRγ restored the apoptotic signal, whereas mutating the 2 tyrosines contained in the FcRγ ITAM abolished the apoptotic signal. These results show that FcαRI can not only mediate activating and inhibitory signals involved in proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions but can also control cell survival in a manner that depends on a functional ITAM. These data provide a mechanistic explanation for the involvement of IgA in apoptosis18,34 and identify FcαRI as the target receptor.

Although FcαRI-mediated apoptosis required intact signaling through the ITAM of the associated FcRγ adaptor, some substantial differences to previously described proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions were noted. The mAb A3, which was incapable of anti-inflammatory signaling after monomeric targeting of FcαRI, readily induced apoptosis. The A3 mAb recognizes the interdomain between the first and second immunoglobulin-like domains of FcαRI, whereas the other 3 functional antibodies used here and in previous studies recognize the second immunoglobulin-like domain.5,35 Furthermore, whereas monomeric IgA induced inhibitory signaling, it failed to promote apoptosis in high serum conditions. IgA, however, induced apoptosis in low serum conditions, suggesting that it required a second signal. Given that IgA is present at high concentrations in human blood, the relevant apoptotic signals must be suppressed to avoid apoptosis of FcαRI-bearing blood cells. IgA can, however, enhance programmed cell death in the presence of low serum concentration indicating requirements for other signals, and this phenomenon might come into play in inflammatory sites where stress and ischemic conditions predominate and thus can provide additional signals for IgA-mediated apoptosis.

The data obtained with FcαRI are reminiscent of those obtained with other ITAM-bearing receptors in the immune system, including antigen receptors on B and T cells (BCR and TCR), respectively. Apoptosis triggered by BCR and TCR is crucial for establishing the lymphocyte repertoire.36,37 It is generally agreed that strong engagement promotes negative selection through apoptosis, whereas engagement with lower-affinity ligands leads to clonal expansion. Both responses crucially depend on phosphorylation of ITAM tyrosines,19,38,39 but qualitative differences may occur among the different ITAMs of the associated subunits.40-42 Our data on FcαRI also point to a crucial role of the FcRγ ITAM in cell activation, inhibition, and apoptosis. However, what determines the different signals and outcomes is unclear. Our previous studies of inhibitory function suggested that weak phosphorylation of the FcRγ ITAM after monomeric targeting led to preferential recruitment of SHP-1 phosphatase rather than Syk, which recruited to a heavily phosphorylated ITAM following sustained multimeric aggregation.5 Our present data suggest that monomeric targeting provides also a strong apoptotic signal. However, multimeric signals also induced apoptosis (albeit at somewhat lower levels), suggesting a complex relationship and the need for specific additional signals. This is supported by our data showing that the natural ligand, IgA, induces apoptosis only in medium containing little or no serum. This putative requirement for additional signals may be overcome in very strong conditions of FcαRI aggregation, as recently reported for human neutrophils.18 Independently of these considerations, our data suggest that FcαRI signaling activates an intrinsic caspase-dependent pathway, because apoptosis induction by FcαRI was essentially blocked by the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. One of the downstream targets is caspase-3, the proform of which is rapidly cleaved into the active form in RBL-cell transfectants, blood monocytes, and monocytic cell lines.

Our previous studies on the inhibitory function of IgA suggested that the ITAM-dependent anti-inflammatory action critically involves SHP-1, similarly to ITIM-mediated inhibition.5 Interestingly, SHP-1–mediated inhibitory signals block apoptosis of B and T cells,12,15 whereas SHIP recruitment attenuates a proapoptotic signal initiated by FcγRIIB.13 Here, decrease of SHP-1 expression in FcαRI transfectants induced by siRNA promoted an increased susceptibility to the apoptotic effect of anti-FcαRI Fab suggesting a crucial role for the physiologic levels of SHP-1 to regulate the balance between FcαRI-mediated apoptosis and previously described inhibitory signaling.5 SHP-1 may thus represent an important target in the switch mechanisms between these functions.

Finally, we show that FcαRI is expressed in some leukemic cell lines and thus FcαRI targeting might be useful for treating tumors that are susceptible to FcαRI-mediated apoptosis. Indeed, tumor formation and progression after subcutaneous grafting of human FcαRI-bearing RBL cells in nude mice were prevented or arrested by an FcαRI-targeting Fab but not by an irrelevant control Fab.

Taken together, our data show that FcαRI is a new apoptotic module that, in addition to its anti-inflammatory, inhibitory signaling activity, may be important for controlling tumor growth. FcαR is thus a highly versatile receptor that can trigger multiple responses ranging from activation and inhibition to the triggering of apoptosis, depending on the physiologic context. This versatility might have therapeutic implications, both in inflammation5 and, as shown here, in cancer.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contribution: Y.K. designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; H.T. performed apoptotic nuclei analysis; S.P. performed transfectant analysis; D.E. performed apoptosis inhibitor experiments; C.G.-M. performed siRNA experiments; M.P. designed inhibitor and biochemical experiments; U.B. interpreted and designed experiments and wrote the manuscript; R.C.M. conceived the idea, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by INSERM and a grant from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (no. 3613). We thank M. Arcos-Fajardo, H. Cohen, and J. Bex for technical support and help in animal care.