Geyeregger and colleagues demonstrate that liver X receptor agonists can down-regulate human dendritic cell activation of T cells at the level of the immune synapse.

G. B. Shaw's play, A Doctor's Dilemma, honored the concepts of phagocytosis (large-particle endocytosis) and opsonization (antibody/antigen binding) described by Metchnikoff and Ehrlich, winners of the 1908 Nobel Prize in Medicine.1 One theme of Shaw's 1906 play was that the proper use of phagocytosis and opsonization would cure disease. Medicine was focused on the control and eradication of infectious microbes in the preantibiotic era. Nearly 100 years later, the modern-day phagocytes, dendritic cells (DCs), are important regulators of the antigen-specific immune response. There are 2 major types of human DCs: lymphoid and myeloid. DC antigen processing and cell surface expression result in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II restricted antigen responses. The liver X receptor α (LXRα) and LXRβ are nuclear receptors that bind oxidized cholesterols (oxysterols) and dimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXRs). The latter have been shown to influence granulocyte/monocyte cell development.2 LXRs have been implicated in lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses (reviewed in Kalany and Mangelsdorf3 and Zelcer and Tontonoz4 ). After oxysterol association, LXRs bind nuclear DNA LXR-responsive elements (LXRLEs) as a dimer, with RXR resulting in gene transcription changes during lipid metabolism and inflammation.

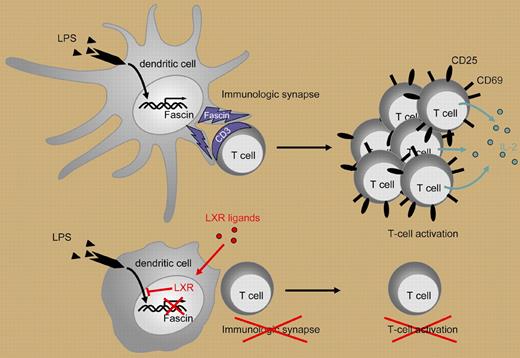

During inflammation, DCs present antigen in the context of the MHC class II molecules to the CD 4 helper T-lymphocyte (T-cell) subset Th1, generating a CD4 T-cell Th1 activation response. The T-cell/DC interaction occurs at the immune synapse (IS) that forms during this cellular interaction. The IS depends on an intact cytoskeleton for positioning membrane ligands and receptors. Actin forms cytoskeletal bundles that assist in the formation of cellular projections, in this case, dendrites. A component of the cytoskeleton matrix is fascin, a monomeric actin filament–bundling protein that participates in the DC dendrite formation and cellular interaction (reviewed in Edwards and Bryan5 ).

In a well-designed series of experiments, Geyeregger and colleagues demonstrate a novel approach to the selective control of human myeloid DC maturation and function through the LXR and fascin pathways. The authors first demonstrate that myeloid DCs express high levels of LXRα mRNA. After exposure to LXR agonists, myeloid DCs were poor stimulators of the CD4 T-cell Th1 activation response as measured by decreased CD25 and CD69 expression and decreased IL-2 and IFN-γ production. The inhibition of DC stimulation was not mediated by aberrant cell surface molecule expression as there was minimal impact on DC-associated membrane markers including CD14, CD80, and HLA-DR. The authors show that LXR agonist treatment impaired DC-mediated T-cell activation after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation but not after CD40L-induced maturation. This differential effect is mediated by LXR agonist down-regulation of fascin expression causing the lack of actin bundling and inhibition of IS formation (Figure 1). Thus, there is differential regulation of DC function. Of note, other investigators have shown that activated T cells induce DC cytoskeletal reformation via the CD40L/CD40 interaction.6 Further investigation will be necessary to determine if the T-cell–mediated CD40L/CD40 interaction can bypass this form of DC inhibition. This disclosure of steps in DC signaling and T-cell activation will provide further insight in DC physiology and may lead to novel agents and approaches for modulating the inflammatory response in autoimmunity and alloimmunity. The LXR agonists may prove to be useful agents for inhibiting myeloid DC activation of the Th1 response when suppression of immune activation is indicated. Was G. B. Shaw right? “Stimulate the Phagocytes” may be necessary for microbial elimination but “Dampen Down the Phagocytes” may more appropriate for modulating the immune response.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces dendritic cell (DC) maturation and fascin production. T-cell activation by DCs depends on formation of an immune synapse (IS). Ligand-induced activation of LXR in DCs inhibits the LPS-induced expression of fascin, an actin-bundling protein that promotes actin bundle formation and is essential for IS formation. By this means, LXR agonists prevent efficient T-cell activation as indicated by diminished proliferation, decreased expression of activation markers (CD25, CD69), and decreased cytokine production (eg, IL-2).

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces dendritic cell (DC) maturation and fascin production. T-cell activation by DCs depends on formation of an immune synapse (IS). Ligand-induced activation of LXR in DCs inhibits the LPS-induced expression of fascin, an actin-bundling protein that promotes actin bundle formation and is essential for IS formation. By this means, LXR agonists prevent efficient T-cell activation as indicated by diminished proliferation, decreased expression of activation markers (CD25, CD69), and decreased cytokine production (eg, IL-2).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ▪

The author wishes to acknowledge Drs J. Baum, J. R. David, and R. S. Schwartz, who taught him how to study the past so as to appreciate the future, and Dr Thomas Stulnig, who provided Figure 1.