New therapies for amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis are sorely needed. This issue of Blood brings encouraging results from 3 studies of new and old antimyeloma treatments for this lethal multisystemic disorder. Dispenzieri and colleagues and Sanchorawala and colleagues studied lenalidomide with and without dexamethasone, and Wechalekar and colleagues combined cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, and thalidomide in their larger study.

Amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis results from the deposition of light chains prone to fibril formation produced by “dangerous small B-cell clones.”1(p2520) For the last 2 decades, treatment approaches have attempted to reduce the clones by using antimyeloma regimens, relying on the hypothesis that amyloid fibril deposition into various organs is a dynamic process and will be reduced once production of amyloidogenic light chains is eliminated. Unfortunately, clonal and organ response rates to standard antimyeloma therapy have been low. The best response rates occur following high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation, but only a minority benefit due to high mortality and morbidity rates.2,3

The 2 phase 2 studies of 22 and 24 patients of the recently FDA-approved, but costly IMiD, lenalidomide, by Dispenzieri and colleagues and Sanchorawala and colleagues are very similar. In both studies, the usual myeloma dose was too toxic for amyloidosis patients, resulting in high early dropout rates and few responses. Addition of high-dose dexamethasone to reduced doses of lenalidomide resulted in good overall hematologic (clonal) response rates of 43% and 47%, in Dispenzieri et al and Sanchorawala et al, respectively. Organ responses, however, occurred in only 23% and 17% of the patients, mainly after clonal responses. Toxicity continued to be a problem, with significant adverse effects occurring in up to 86% of patients, including myelosuppression, fatigue, infections, rashes, and thromboembolic events. Four deaths occurred in each study, apparently due to amyloid progression rather than toxicity.

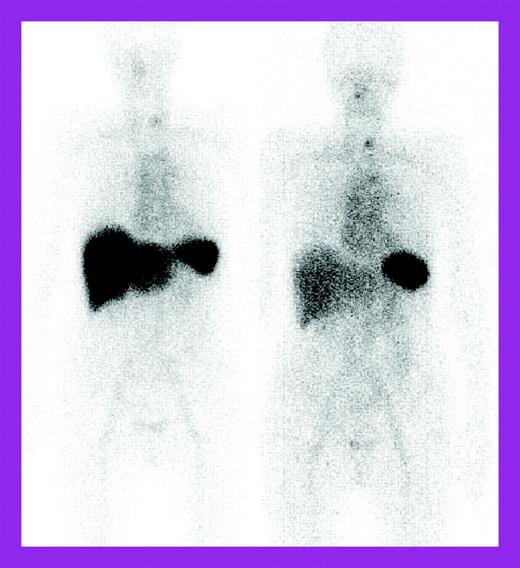

The study by Wechalekar and colleagues is a larger retrospective study of 75 patients treated with a risk-adapted regimen of cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, and thalidomide and followed at the National Amyloidosis Centre, United Kingdom, with 123I–serum amyloid P component (SAP) scintigraphy as well as the usual light chain measurements. These patients were considered ineligible for high-dose chemotherapy by British guidelines.4 The 74% clonal response rate was impressive for a nontransplantation regimen, but organ responses lagged behind at 27%. 123I-SAP scans showed regression of liver deposits in responding patients (see the figure) but less often, decreases in kidney deposits. Fewer patients had significant adverse effects; treatment-related mortality occurred in 4%. However, the patients represented only 4.8% of those seen at the Centre over 5 years, raising the question of possible selection bias, although patient characteristics were similar to those described in the other 2 studies, except that severe autonomic or peripheral neuropathy patients were excluded.

Serial 123I-labeled anterior whole-body SAP scintigraphy. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 457.

Serial 123I-labeled anterior whole-body SAP scintigraphy. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 457.

These 3 studies' clonal response rates in these seriously ill patients and the durability of the responses in the longer United Kingdom study are encouraging. However, the poor organ response rates in all 3 studies point to the clear need for new treatment modalities that can mobilize amyloid out of the tissues more efficiently while the clones are being reduced with less toxic (and less expensive) drugs.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ▪