To some extent, a graft-versus-host reaction occurs in all recipients after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), but not all patients suffer the tissue injury and resulting symptoms and signs recognized as GVHD. At the same time, infections and regimen-related toxicity involving the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract occur frequently after HCT, often making it very difficult to distinguish GVHD from other complications. An even greater clinical problem is the difficulty of distinguishing GVHD activity, a process that may be amenable to immunosuppressive treatment, from GVHD damage, an end result that requires tissue repair rather than immunosuppression.

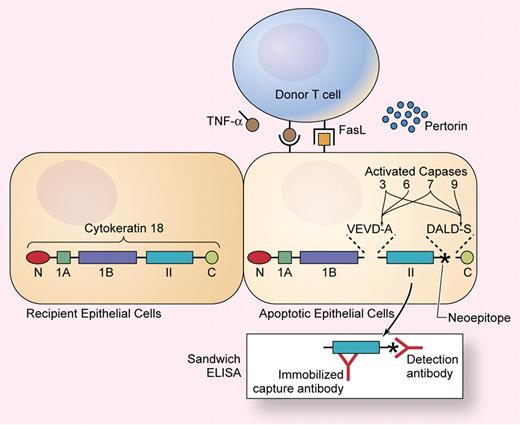

To a large extent, tissue injury in acute GVHD results from apoptosis of epithelial cells, mediated by donor T cells through the actions of perforin, Fas ligand (FasL), and membrane-bound or secreted tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (see figure). Sparse apoptotic cells can be recognized in biopsy specimens from patients with GVHD, but histopathologic changes are difficult to measure quantitatively, and biopsies are susceptible to sampling error. Apoptosis results from a cascade of intracellular protein cleavage events mediated in part by caspase proteases. Studies of cell biology and biochemistry in the 1990s demonstrated that caspase proteases cleave certain cytokeratins and other intermediate filament proteins and that cleavage products from these proteins could be used as markers of apoptosis (see figure).

Cytokeratin 18 contains N and C terminal globular domains flanking 3 α-helical subdomains. Activated capases cleave cytokeratin 18 at sequences within linkers on both sides of the α II domain, exposing a neoepitope (indicated with an asterisk) that can be detected in a sandwich ELISA. Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

Cytokeratin 18 contains N and C terminal globular domains flanking 3 α-helical subdomains. Activated capases cleave cytokeratin 18 at sequences within linkers on both sides of the α II domain, exposing a neoepitope (indicated with an asterisk) that can be detected in a sandwich ELISA. Illustration by Kenneth Probst.

In a retrospective study in this issue of Blood, Luft and colleagues have shown that measurement of a cytokeratin 18 fragment released into the plasma by caspase cleavage can be used as a sensitive and quantitative biomarker of hepatic and intestinal epithelial apoptosis caused by GVHD. The tight coupling of this biomarker with apoptosis offers a convenient method for classifying the causes of abnormal liver and gut function after HCT according to the underlying mechanism of epithelial injury. The proposed use of cytokeratin 18 fragment assays as a laboratory measure of GVHD requires confirmation in prospective studies. Blinded testing in larger populations will be needed in order to validate the reported high sensitivity of this method for diagnosing GVHD, determine the extent to which other complications after HCT might also cause apoptosis, establish the range of normal values, and identify the threshold concentrations that provide optimal sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing GVHD in different settings. Additional work is needed to develop similar assays that measure apoptosis in cutaneous basal keratinocytes, since cytokeratin 18 is not expressed in the skin.

If prospective studies confirm and extend the results of Luft and colleagues, then one day it should be possible to use measurements of cytokeratin 18 fragments and other biomarkers as laboratory tools together with clinical judgment in tailoring immunosuppressive treatment for individual patients. In addition, quantitative and sensitive biomarkers of apoptotic epithelial injury could be applied as incisive measures in experimental studies and clinical trials related to GVHD.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■