Here, we demonstrate that carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-1 (CEACAM1) is expressed and co-localized with podoplanin in lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) of tumor but not of normal tissue. CEACAM1 overexpression in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMECs) results in a significant increase of podoplanin-positive cells in fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses, while such effects are not observed in CEACAM1 overexpressing human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVECs). This effect of CEACAM1 is ceased when HDMECs are transfected with CEACAM1/y− missing the tyrosine residues in its cytoplasmic domain. CEACAM1 overexpression in HDMECs leads to an up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor C, -D (VEGF-C, -D) and their receptor vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) at mRNA and protein levels. HDMECs transfected with CEACAM1 but not those with CEACAM1/y− show enhanced expression of the lymphatic markers Prox1, podoplanin, and LYVE-1. Furthermore, Prox1 silencing in HDMECs via small interfering RNA blocks the CEACAM1-induced increase of VEGFR-3 expression. Number and network of endothelial tubes induced by VEGF-C and -D are enhanced in CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs. Moreover, VEGF-A treatment of CEACAM1-silenced HDMECs restores their survival but not that with VEGF-C and VEGF-D. These data imply that the interaction of CEACAM1 with Prox1 and VEGFR-3 plays a crucial role in tumor lymphangiogenesis and reprogramming of vascular endothelial cells to LECs. CEACAM1-induced signaling effects appear to be dependent on the presence of tyrosine residues in the CEACAM1 cytoplasmic domain.

Introduction

Previous studies showed that not only angiogenesis but also lymphangiogenesis, which is defined as induction of the outgrowth of lymphatics from preexisting lymphatic vessels, play a crucial role in tumor growth and metastasis.1,,–4 Both vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) and VEGF-D induce lymphangiogenesis via the vascular endothelial growth factor 3 (VEGFR-3; Flt-4) and also bind to VEGFR-2 (KDR).5,6 The expression of VEGFR-3 is regulated by the homeobox transcription factor Prox1, a marker for lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs).7,8 Whereas the significance of different cell adhesion molecules for angiogenesis has been well documented,9,,,,–14 their role in lymphangiogenesis has not yet been studied sufficiently

We showed that soluble CEACAM1 (carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-1) functions as a potent angiogenic factor and as a major morphogenic effector for VEGF.9,15 CEACAM1 is expressed in endothelial cells of newly formed small blood vessels of angiogenic tissues such as in tumors, regeneration of endometrium, and placenta and wound healing, but not in quiescent blood vessels of normal human tissues.9,15 Recently, we showed that membrane-bound CEACAM1 also acts pro-angiogenic. Its endothelial overexpression resulted in up-regulation of potent pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF-A, angiopoietins Ang1 and Ang2, angiogenin and interleukin 8 (IL-8).16 CEACAM1 silencing in human microvascular endothelial cells via small interfering RNA (siRNA) abolished the tube-forming effect of VEGF in vitro.16 In contrast, CEACAM1 overexpression in bladder cancer cell lines suppresses, but CEACAM1 silencing activates angiogenesis and increases the expression of pro-angiogenic and prolymphangiogenic factors such as VEGF-C and -D.17

Based on these findings, we wanted to study whether and how CEACAM1 is involved in lymphangiogenesis or in reprogramming of vascular endothelial cells (VECs) into LECs. Our present data demonstrate that CEACAM1 is expressed in endothelia of lymphatic vessels of different human tumors such as bladder and prostate carcinomas and testicular seminoma, while lymphatic vessels of nonpathologic tissues of the same organs remain negative. Using overexpression and gene silencing as well as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) scan analyses we found that CEACAM1 plays a role in the reprogramming of VECs to LECs, and in the induction and morphogenetic events of tumor lymphangiogenesis, particularly via interaction with the expression of VEGFR-3 and Prox1. By this mechanism, CEACAM1 may also play a role in dissemination of tumor cells via lymphatic vessels.

Materials and methods

Growth factors and antibodies

VEGF-A (VEGF165), VEGF-C, and VEGF-D were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Polyclonal antibodies against VEGF-A and VEGFR-3 (Flt-4) were obtained from SantaCruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Goat polyclonal antibodies against VEGF-C and VEGF-D were purchased from R&D Systems. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Prox1, LYVE-1, and podoplanin were obtained from Reliatech (Braunschweig, Germany). Affinity-purified monoclonal antibody 4D1/C2 against CEACAM1 was produced as described previously.18 The antibody was kindly provided by the group of Prof C. Wagener, Department of Clinical Chemistry, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany. Further, the following antibodies were used: the mAb 4/3/17 against CEACAM1/CEACAM5, mAb 9A6 against CEACAM6, and mAb BAC2 against CEACAM7 (Genovac, Freiburg, Germany), mAb 80H3 against CEACAM8 (Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France), anti-CEACAM3/CEACAM5 (Zymed, San Francisco, CA), anti-podoplanin clone 18H5 (Acris, Hiddenhausen, Germany), mAb against VEGFR-3 (clone 9D9F9; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), mAb against integrin α5/β3 (clone 23C6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and mAb against Vimentin (clone V9; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

Cells and tissues

Paraffin-embedded tissue pieces from normal and invasive tumor of prostate and bladder, as well as early preinvasive forms such as prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), were available in the Department of Pathology, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany. Paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from human testis and testicular cancer (seminoma and carcinoma-in-situ, CIS) were available in the Institute of Anatomy I, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany. Tissue pieces were fixed either with 4% paraformaldehyde or with Bouin solution and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemical studies. HDMECs (human dermal microvascular endothelial cells) were grown in MV medium containing 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), both supplied from PromoCell (Heidelberg, Germany). The cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air.

Transient transfection of HDMECs with CEACAM1 versus CEACAM1/y− and cotransfection of HDMECs with CEACAM1 + Prox-1-siRNA

Cloning of full-length cDNA encoding CEACAM1 was performed as described.16,17 The cDNA encoding double-mutant Y488, 515F19 was kindly provided by the group of Prof C. Wagener, Department of Clinical Chemistry, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1/Hygro(−), and designated as CEACAM1/y−. For Prox1 gene silencing, predesigned siRNA was obtained from Ambion (Ambion, Austin, TX) and tested for its efficiency in endothelial cells. Target sequence from firefly luciferase gene was chosen as a control for CEACAM1-silencing studies.16,17 Transient transfection of HDMECs was performed using 2.0 μg of DNA/siRNA and HMVEC-L Amaxa Nucleofection Kit (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany), along with the program S-05 on the Nucleofector device.16 For cotranfection experiments, 1 μg of each DNA or RNA was used. The efficiency of transfection was controlled by the parallel transfection for GFP (green fluorescent protein) and was estimated at approximately 60%.

Endothelial survival assay

This assay was performed as we recently described.16 HDMECs were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-CEACAM1 or with the empty vector pcDNA3.1(−) as control. For CEACAM1 silencing, HDMECs were transfected with siRNAs targeting cDNA sequences of CEACAM1 gene specifically. Luciferase-siRNA was used as a control.17 In wells containing CEACAM1, versus empty vector-transfected HDMECs polyclonal goat VEGF-C and VEGF-D, antibodies were added at a concentration of 600 ng/mL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Furthermore, CEACAM1- versus luciferase-silenced HDMECs were treated with VEGF-A (VEGF165), VEGF-C, and VEGF-D (R&D Systems) at a concentration of 50 ng/mL. The cells were controlled daily and photographed via a phase contrast microscope equipped with a digital camera (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The areas of cell detachment were measured using the morphometric program Optimas (Optimas, Seattle, WA).16

Adenoviral vector construction and transfection of HDMEC

To overexpress the membrane-bound CEACAM1 in human vascular endothelial cells in a glycosylated form comparable to native CEACAM1, we used the homologous recombination technique of adenoviral vectors20 as we also reported for CEACAM1 expression previously.9 The viral lysate was used to infect HEK293 cells to generate a high titer of viral stocks, which was purified and used then to transfect HDMECs. After 2 to 3 days, cells were harvested and used for RNA isolation. As control, wild-type as well as LacZ-virus–transfected endothelial cells were employed.16

RNA isolation and reverse transcription

Total RNA from wild-type, adenoviral LacZ–transfected, and CEACAM1-transfected HDMECs was extracted 48 to 72 hours after transfection using Trizol Reagent (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) following the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA from empty pcDNA3.1 vector, pcDNA3.1-CEACAM1/y−, and CEACAM1-transfected HDMECs as well as from HDMECs co-transfected with CEACAM1 + luciferase-siRNA and with CEACAM1 + Prox1-siRNA was extracted 24 to 48 hours after transfection using RNA-Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Three to five micrograms of total RNA each were reverse transcribed using the You-Prime First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham-Pharmacia, Braunschweig, Germany), resulting in cDNA, which was subsequently analyzed by gene array (purchased by SuperArray, Bethesda, MD) and by quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using LightCycler system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) for studying the expression of angiogenic factors.

Gene array

For determining pathway-specific gene expression profiling, nonradioactive GEArray assay purchased from SuperArray (Bethesda, MD) was performed. Briefly, total RNA from CEACAM1- and LacZ-transfected as well as wild-type HDMECs were employed as a template for biotinylated cDNA synthesis, according to the procedure of the supplier. The cDNA probes were then hybridized to gene-specific cDNA fragments spotted on the membranes and exposed to an X-ray film. The spotted and hybridized areas were quantified by densitometric analyses (Optimas, Seattle, WA).16

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR using LightCycler System

Real-time RT-PCR analyses for VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and their receptor VEGFR-3 were carried out on the LightCycler System (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), as described originally by Wittwer et al21 on the Opticon System (MJ Research-Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Primer sequences for VEGF-C and -D as well as for the housekeeping gene glycerin aldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were designed, as recently published.16,17

SDS-PAGE and Western blots

Protein extracts (15-30 μg total protein) prepared with the lysis buffer solution containing 100 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) and 500 mM sucrose were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–sample buffer before being applied into a 10% nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for the detection of Prox1, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D, and 8% nonreducing SDS-PAGE for the detection of VEGFR-3. After electrotransfer to nitrocellulose membranes, these were processed with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, followed by detection using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting reagents (Amersham). The intensity of the bands was determined by means of comparable densitometric analyses (Optimas).

FACS analyses

HDMECs (106 cells) were transiently transfected with vectors containing CEACAM1–4L (= CC1), CEACAM1–4L-ITIMdel (= CC1/Y−), siCEACAM1, or siControl using the HMVEC-L Nucleofector kit (Amaxa Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Thereafter, cells were cultivated for 24 hours to 36 hours before trypsinisation and flow cytometric analyzes. For FACScan 100 000 cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL primary antibody, washed twice, and incubated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled secondary goat Fab2 antimouse antibody (Jackson Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Probes were washed 3 times and analyzed with the FACScalibur flow cytometer and the CellQuest software (BD, Heidelberg, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for CEACAM1, VEGFR-3, and podoplanin was performed on paraffin sections obtained from heathy tissues and different human tumors including prostate, urinary bladder, and testis, using the human CEACAM1-specific monoclonal antibody 4D1/C2 and specific antibodies against VEGFR-3 and CD34, according to the procedure described previously.22,23 Immunofluorescence staining for co-localization of podoplanin and CEACAM1 were performed using antibodies mentioned above. In some cases, the combination of conventional peroxidase technique, resulting in a yellow-brownish staining, and the glucose-oxidase technique, resulting in a dark staining, was used for double immunostaining. FITC- and tetramethylrhodamine-5(and 6)-isothiocyanate (TRITC)–conjugated secondary antibodies were used for the visualization of the specific fluorescence staining.

Statistical evaluation

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, San Francisco, CA), and the significance was accepted at P values less than .05 and calculated using the Student t test (2 side).

Image acquisition and manipulation

Slides were observed with a Leica DMRM light microscope equipped with a digital camera (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) model Leica DFC 320, using lenses HC PLAN FLUOTAR at 5× and 10×/0.3 NA, HCX PLAN APO at 40×/0.85 NA, and CDRR and PL FLUOTAR OIL PH3 at 100×/1.3 NA. Image acquisition was performed using Leica software IM50 (Leica Microsystems) for tissue sections stained according to the peroxidase-glucoxidase technique. Tissue sections used for immunofluorescence staining were observed with a Leica TCS SPE laser confocal microscope with inverse DMI 4000 CSQ VIS and equipped with a Leica digital camera (Leica Microsystems) model DFC 300 FX R2, using lenses HC PL FL at 10×/0.3, HCX PL FL at 40×/0.75, HCX PL APO at 63×/1.40 NA oil objective, N PLAN L at 20×/0.35 PH1, N PLAN PL FL L at 20×/0.40, HCX PL FL L at 40×/0.60; images were observed using Leica Application Software (LAS) SPE Basic (Leica Microsystems). Endothelial survival assay was observed with a Leica DM IL inverse phase contrast microscope equipped with a digital camera (Leica Microsystems) model Leica DFC320 using lenses HI PLAN at 4×/0.1, HI PLAN at 10×/0.22, and HI PLAN at 20×/0.30. All images were further processed using Adobe Photoshop version 7.0 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Results

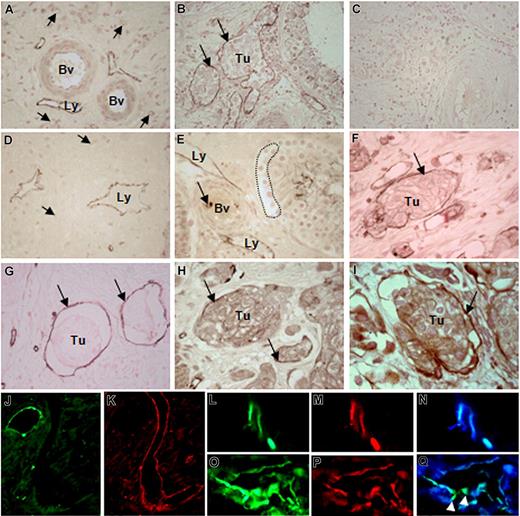

CEACAM1 expression in tumor-associated but not in normal lymphatic vessels

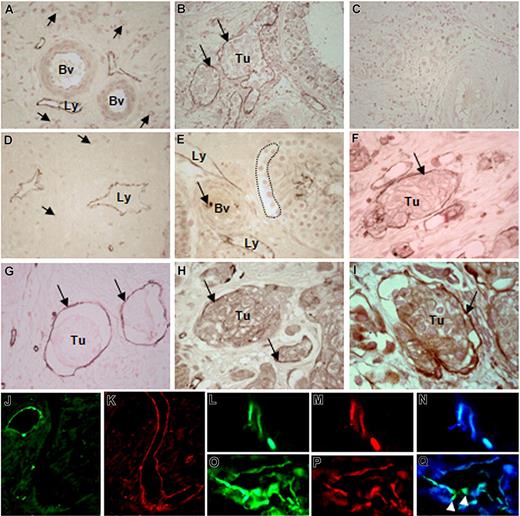

In the surrounding areas of human testicular tumors, lymphatic vessels that were mostly localized near the large arteries or veins exhibited CEACAM1 staining (Figure 1A), whereas large and small blood vessels themselves remained negative. These quiescent small blood vessels exhibited peri-endothelial cells in their wall, which were not found in the lymphatics as normally expected. This is an essential morphologic criterion for distinguishing the lymphatics from the blood vessels. Often, the CEACAM1-positive lymphatics were filled with tumor cell clusters (Figure 1B) once tumor cells invaded testicular interstitium. Corresponding controls with the secondary antibody showed no significant immunostaining (Figure 1C). Such activated lymphatics expressing CEACAM1 also were found in the tumor surrounding area of prostate (Figure 1D) and urinary bladder (not shown). To determine when exactly CEACAM1 is up-regulated in LECs during tumor development, we performed immunohistochemical studies on human testicular and prostate tissues containing CIS of testis and PIN of prostate, which are both considered early noninvasive tumor forms needing a relatively long period to transform to an invasive phenotype. These studies revealed a clear presence of CEACAM1 in lymphatics in the interstitium (Figure 1E) before invasion of tumor cells into the interstitium and, more interestingly, before CEACAM1 detection in vascular endothelia as exemplarily shown for CIS (Figure 1E).

CEACAM1 expression in endothelial cells of tumor-associated lymphatics. (A) Lymphatics (Ly) in surrounding tumor cell–free area of testicular seminoma exhibit CEACAM1 immunostaining, while middle-sized (Bv) and small (→) blood vessels remain negative. (B) Lymphatics (→) containing clusters of seminoma (Tu) are positive for CEACAM1. (C) No immunostaining could be detected in control sections of testicular tumor tissue. (D) Similarly, in prostate carcinoma, lymphatics (Ly) of tumor-surrounding area, far from tumor area, express CEACAM1. (E) Endothelia of lymphatics (Ly) in close approximation to carcinoma-in-situ cells (…) in a seminiferous tubule exhibit CEACAM1 immunostaining, while neighboring blood vessels (Bv) are negative for CEACAM1 at this phase of tumor development. (F) Granulocytes (→) within the blood vessel lumen are stained as expected. In the invasive bladder cancer, CEACAM1 immunostaining is visible in endothelia of lymphatics (→) containing tumor cell groups (Tu) similar to testicular seminoma in panel B. Similar cells are positive for CD34 (→), indicating their endothelial origin (G); they also exhibit VEGFR-3 (Flt-4; →; H). (I) Double-immunostaining using CEACAM1 antibody 4D1/C2 and VEGFR-3 antibody demonstrates the co-localization of both (→), suggesting the lymphatic character of these cells. Sections in panels A-I are counterstained with calcium red. Immunofluorescence staining for CEACAM1 in a healthy area of human prostate demonstrates the expected localization in the healthy epithelium (J), while neighboring large and small lymphatics from the same area, which are marked by staining for podoplanin (K), do not exhibit CEACAM1. Double-immunofluorescence staining for CEACAM1 and podoplanin in prostate cancer tissue shows clear staining for CEACAM1 (L) and for podoplanin (M) in the same lymphatic vessels, as it is also confirmed by overlay (N). In a further tumor-associated lymphatic vessel, both CEACAM1 (O) and podoplanin (P) are present, but remarkably, single endothelial cells ( ) integrated into the lymphatic endothelium exhibit only CEACAM1 (green fluorescence staining; Q).

) integrated into the lymphatic endothelium exhibit only CEACAM1 (green fluorescence staining; Q).

CEACAM1 expression in endothelial cells of tumor-associated lymphatics. (A) Lymphatics (Ly) in surrounding tumor cell–free area of testicular seminoma exhibit CEACAM1 immunostaining, while middle-sized (Bv) and small (→) blood vessels remain negative. (B) Lymphatics (→) containing clusters of seminoma (Tu) are positive for CEACAM1. (C) No immunostaining could be detected in control sections of testicular tumor tissue. (D) Similarly, in prostate carcinoma, lymphatics (Ly) of tumor-surrounding area, far from tumor area, express CEACAM1. (E) Endothelia of lymphatics (Ly) in close approximation to carcinoma-in-situ cells (…) in a seminiferous tubule exhibit CEACAM1 immunostaining, while neighboring blood vessels (Bv) are negative for CEACAM1 at this phase of tumor development. (F) Granulocytes (→) within the blood vessel lumen are stained as expected. In the invasive bladder cancer, CEACAM1 immunostaining is visible in endothelia of lymphatics (→) containing tumor cell groups (Tu) similar to testicular seminoma in panel B. Similar cells are positive for CD34 (→), indicating their endothelial origin (G); they also exhibit VEGFR-3 (Flt-4; →; H). (I) Double-immunostaining using CEACAM1 antibody 4D1/C2 and VEGFR-3 antibody demonstrates the co-localization of both (→), suggesting the lymphatic character of these cells. Sections in panels A-I are counterstained with calcium red. Immunofluorescence staining for CEACAM1 in a healthy area of human prostate demonstrates the expected localization in the healthy epithelium (J), while neighboring large and small lymphatics from the same area, which are marked by staining for podoplanin (K), do not exhibit CEACAM1. Double-immunofluorescence staining for CEACAM1 and podoplanin in prostate cancer tissue shows clear staining for CEACAM1 (L) and for podoplanin (M) in the same lymphatic vessels, as it is also confirmed by overlay (N). In a further tumor-associated lymphatic vessel, both CEACAM1 (O) and podoplanin (P) are present, but remarkably, single endothelial cells ( ) integrated into the lymphatic endothelium exhibit only CEACAM1 (green fluorescence staining; Q).

) integrated into the lymphatic endothelium exhibit only CEACAM1 (green fluorescence staining; Q).

In invasive stages of urinary bladder cancer such as pT2-pT4, CEACAM1 was expressed in lymphatics filled with tumor cell clusters (Figure 1F). The endothelial origin of these cells was confirmed by immunostaining for CD34 (Figure 1G). Similar to the CEACAM1 staining, as shown in Figure 1F, VEGFR-3 immunostaining also was found in cells lining lymphatic spaces and angiogenic small blood vessels (Figure 1H). For further characterization, we performed single and double immunostaining for CEACAM1 and VEGFR-3 (Flt-4), which binds VEGF-C and VEGF-D in high affinity. The double immunostaining for CEACAM1 and VEGFR-3 revealed a co-localization of both in the same cells (Figure 1I).

Since VEGFR-3 is also expressed in angiogenicly activated VECs, we performed double-fluorescence immunostaining for CEACAM1 and podoplanin, which is considered to be expressed in LECs but not in VECs. Conformingly, in our extensive studies on human bladder and prostate tissues, podoplanin immunostaining was present in lymphatic vessels but not in blood vessels. In normal area of prostate tissue, CEACAM1 was visible at the luminal epithelial surface of prostate glands as expected but not in large and closely associated lymphatic vessels (Figure 1J), which were clearly positive for podoplanin (Figure 1K). At the marginal zone, and occasionally also within the tumor area of prostate, small lymphatics were positive for both CEACAM1 and pododplanin (Figure 1L-N). Interestingly, in some tumor-associated lymphatics few single endothelial cells were positive only for CEACAM1, as additionally demonstrated by double immunostaining for CEACAM1 and podoplanin (Figure 1O-R).

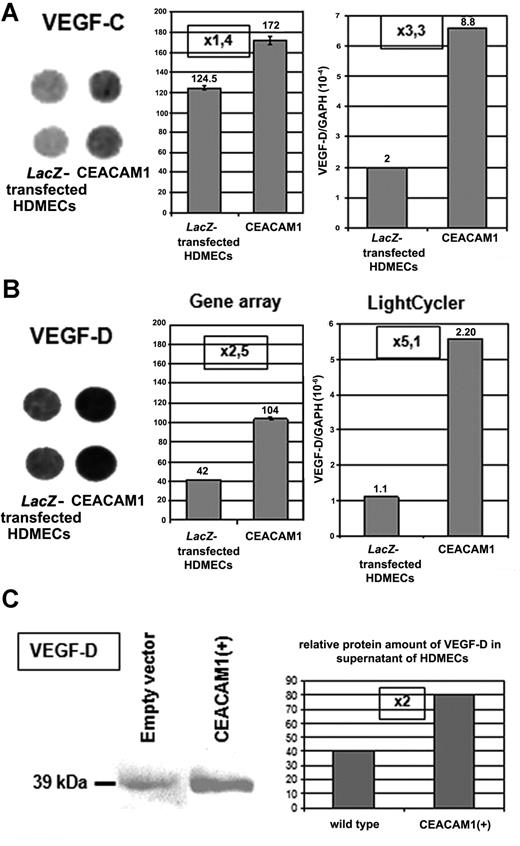

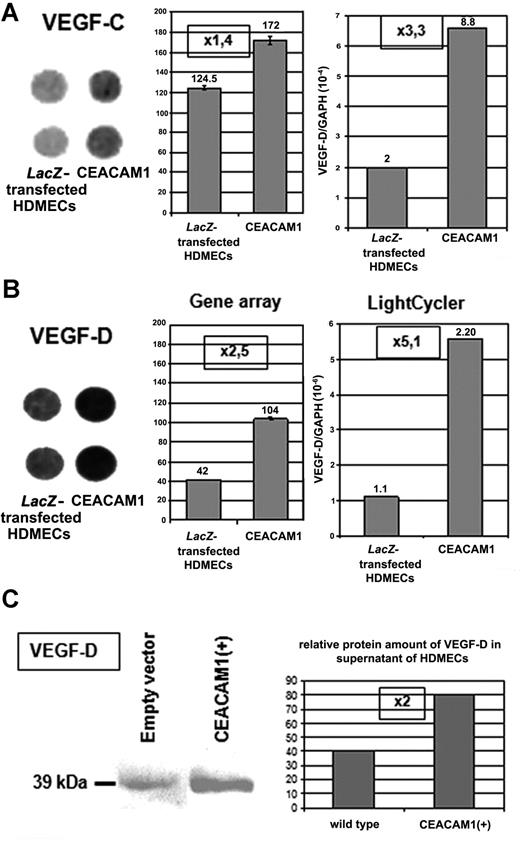

Up-regulation of VEGF-C and -D by CEACAM1 overexpression in HDMECs

In gene array as well as in quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses, we found a significant up-regulation of VEGF-C (Figure 2A) and VEGF-D (Figure 2B) in HDMECs overexpressing CEACAM1 after adenoviral transfection when compared with wild-type or LacZ-transfected HDMECs. Supporting this finding, we found a 2-fold enhanced amount of VEGF-D protein in HDMECs overexpressing CEACAM1 in comparison to the wild-type cells (Figure 2C).

Endothelial CEACAM1 up-regulates the expression of VEGF-C and -D. (A) Overexpression of CEACAM1 in HDMECs results in up-regulation of VEGF-C in gene array as well as quantitative RT-PCR-analyses. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Also, VEGF-D (B) is up-regulated in both analyses even more than VEGF-C. Endothelial CEACAM1 overexpression was performed via adenoviral transfection, and LacZ-transfected HDMECs were used as control. Gene array (left: spots in duplicate, middle panel: densitometric quantification of the spots), LightCycler (right). (C) At protein level, VEGF-D is detectable in a higher amount in CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs in comparison to wild-type HDMECs (left panel) as demonstrated via densitometric quantification, which shows a 2-fold increase (right panel).

Endothelial CEACAM1 up-regulates the expression of VEGF-C and -D. (A) Overexpression of CEACAM1 in HDMECs results in up-regulation of VEGF-C in gene array as well as quantitative RT-PCR-analyses. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Also, VEGF-D (B) is up-regulated in both analyses even more than VEGF-C. Endothelial CEACAM1 overexpression was performed via adenoviral transfection, and LacZ-transfected HDMECs were used as control. Gene array (left: spots in duplicate, middle panel: densitometric quantification of the spots), LightCycler (right). (C) At protein level, VEGF-D is detectable in a higher amount in CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs in comparison to wild-type HDMECs (left panel) as demonstrated via densitometric quantification, which shows a 2-fold increase (right panel).

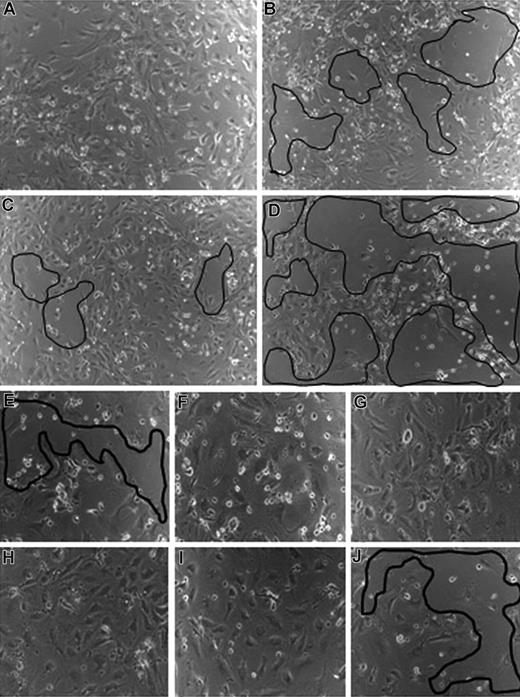

Improved survival of HDMECs by CEACAM1 overexpression via VEGF-C and -D

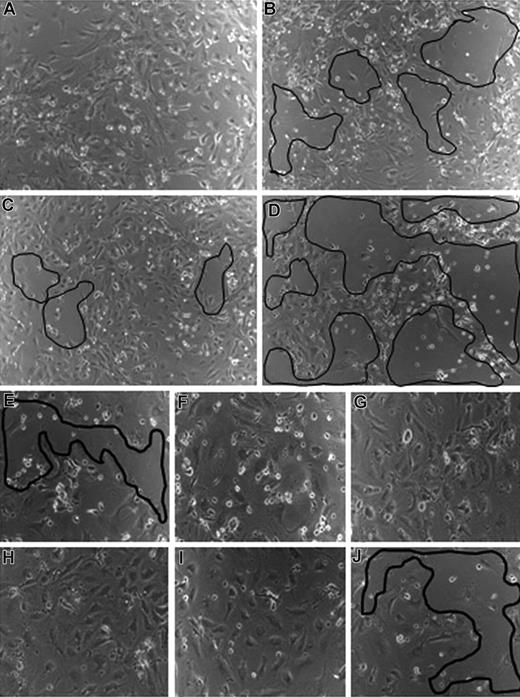

Recently, we demonstrated that CEACAM1 overexpression in HDMECs prolongs their survival in comparison to wild-type or empty vector transfected HDMECs.16 To study whether VEGF-C and VEGF-D are involved in the CEACAM1-mediated endothelial cell survival, we treated CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs with antibodies against VEGF-C and VEGF-D. CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs showed a prolonged survival in comparison to those transfected with empty vector (not shown). In comparison to untreated CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs, which remained nearly confluent and adherent under hunger conditions (Figure 3A), HDMECs treated with anti–VEGF-C (Figure 3B) or anti–VEGF-D (Figure 3C) showed large areas with cell detachment from the culture well. The cell detachment was most prominent when empty-vector transfected HDMECs were treated with anti–VEGF-C (Figure 3D) or anti–VEGF-D (not shown), supporting the essential role of CEACAM1 in endothelial survival.

VEGF-C and -D are involved in CEACAM1-mediated endothelial survival. (A) CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs remain confluent under hunger conditions. In contrast, the treatment of CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs with antibodies against VEGF-C (B) and -D (C) leads to a detachment of endothelial cells from the well (marked areas). The detachment of endothelial cells is most prominent when empty vector-transfected HDMECs were treated with anti–VEGF-C (D). CEACAM1 silencing in HDMECs induces detachment of endothelial cells without any treatment (E), while luciferase-silenced HDMECs remain almost confluent (F). The treatment of CEACAM1- (G) and luciferase-silenced (H) HDMECs with VEGF-A improves their survival. The treatment with VEGF-C improves the survival of luciferase-silenced HDMECs (I) but not that of CEACAM1-silenced HDMECs, as visible by the area of cell detachment (J).

VEGF-C and -D are involved in CEACAM1-mediated endothelial survival. (A) CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs remain confluent under hunger conditions. In contrast, the treatment of CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs with antibodies against VEGF-C (B) and -D (C) leads to a detachment of endothelial cells from the well (marked areas). The detachment of endothelial cells is most prominent when empty vector-transfected HDMECs were treated with anti–VEGF-C (D). CEACAM1 silencing in HDMECs induces detachment of endothelial cells without any treatment (E), while luciferase-silenced HDMECs remain almost confluent (F). The treatment of CEACAM1- (G) and luciferase-silenced (H) HDMECs with VEGF-A improves their survival. The treatment with VEGF-C improves the survival of luciferase-silenced HDMECs (I) but not that of CEACAM1-silenced HDMECs, as visible by the area of cell detachment (J).

Furthermore, in a reverse experimental approach, we silenced CEACAM1 in HDMECs and subsequently treated them with VEGF-A (VEGF165), VEGF-C, and VEGF-D. First of all, the survival of CEACAM1-silenced HDMECs was significantly reduced (Figure 3E) in comparison to luciferase-silenced HDMECs (Figure 3F). VEGF-A alone was able to restore the survival of both CEACAM1- (Figure 3G) and luciferase-silenced (Figure 3H) HDMECs and to keep them in a confluent state. The treatment with VEGF-C and VEGF-D could only improve the survival of luciferase-silenced (Figure 3I) but not that of CEACAM1-silenced (Figure 3J) HDMECs as exemplarily shown for VEGF-C treatment. Further, the length and the network of endothelial tubes induced by VEGF-C (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and VEGF-D (not shown) were significantly increased when these factors were applied to CEACAM1 overexpressing HDMECs in comparison to their application to empty-vector transfected HDMECs or HDMECs overexpressing the mutant CEACAM1/Y− (Figure S1).

Endothelial overexpression of CEACAM1 increases the expression of VEGFR-3

Since the application of VEGF-A, but not that of VEGF-C and VEGF-D, was able to restore the reduced endothelial survival after CEACAM1 silencing in HDMECs, we suspected a relation between endothelial CEACAM1 and the expression of VEGFR-3 (Flt-4). Indeed, we found an up to 8.1-fold increase of the VEGFR-3 protein in the cell extract of CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs (not shown) using Western blot analyses in comparison to empty-vector transfected HDMECs.

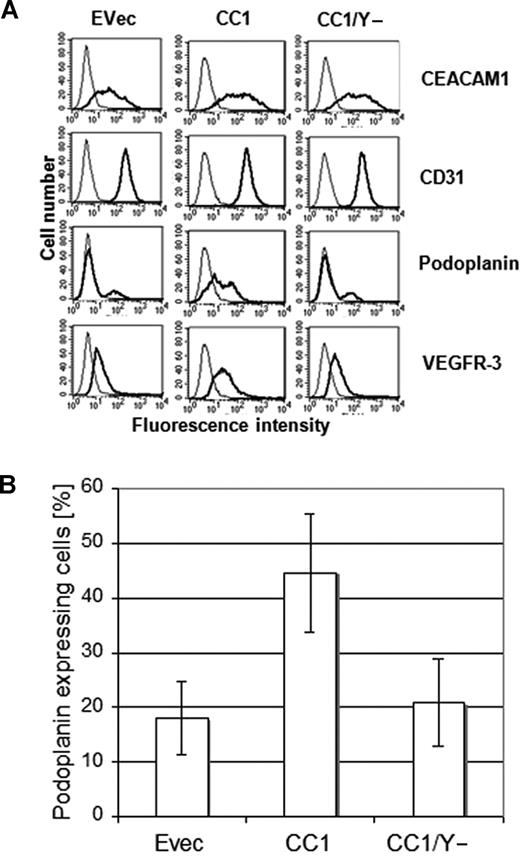

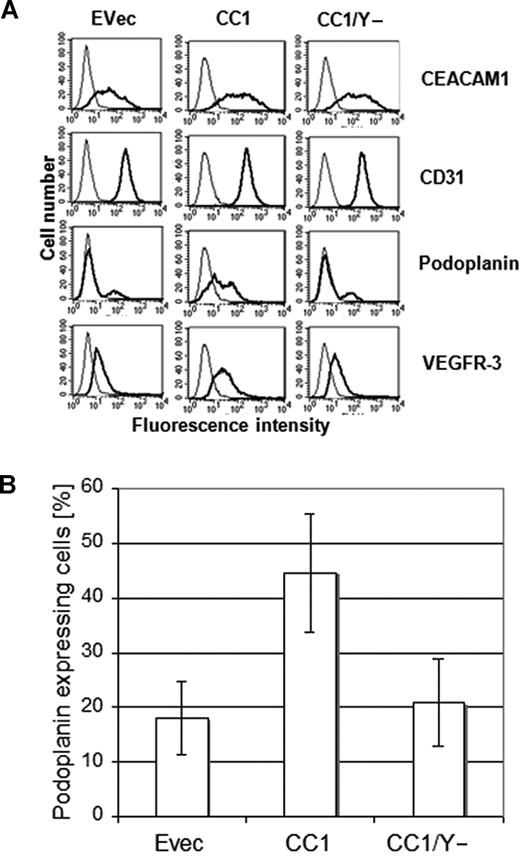

It has been shown that HDMECs are composed of both microvascular and lymphatic endothelial cells. This is also confirmed by our immunocytochemical data showing a positive staining for podoplanin and VEGFR-3 in the fraction of wild-type HDMECs (not shown). Thus, we particularly focused on the expression level of podoplanin in relation to CEACAM1 to evaluate whether CEACAM1 is involved in the lymphatic reprogramming of microvascular endothelial cells. To this aim, we performed FACS analyses on HDMECs transfected for CEACAM1, CEACAM1/Y−, and empty vector 36 hours after transfection. While a low level of endogenous expression of CEACAM1 was detected after transfection with the empty vector (Figure 4A), a significantly higher amount of CEACAM1 was found in HDMECs transfected with CEACAM1 and in those transfected with CEACAM1/Y− (Figure 4A). Remarkably, a significantly increased percentage of podoplanin- and VEGFR-3–positive cells was detectable only among HDMECs transfected with intact CEACAM1 (CEACAM1-L; Figure 4A). To analyze if overexpression of CEACAM1 in HDMECs affects all cell surface molecules or if the CEACAM1-induced effect is mainly restricted to lymphendothelial markers, we examined the CD31 (PECAM1) and α5/β3 integrin expression. Compared with empty-vector transfected cells, neither CEACAM1 nor CEACAM1/Y− altered the CD31 (Figure 4A) and α5/β3 integrin expression (not shown). Interestingly, similar transfection studies on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), which were negative for CEACAM1 and podoplanin in FACS analyses, did not show any change in the expression of podoplanin after CEACAM1 overexpression for 36 hours (not shown). Considering the fact that a certain fraction of HDMECs, per se, stained positive for podoplanin, we improved our analyses by sorting specifically podoplanin-negative HDMECs and subsequently transfecting them with empty vector, CEACAM1, and CEACAM1/Y−. Again, 36 hours after transfection, podoplanin expression was determined by FACS analyses, which again revealed a significantly increased percentage of podoplanin-positive cells among HDMECs transfected with intact CEACAM1 (Figure 4B). In contrast, the percentage of podoplanin-positive cells among HDMECs transfected with empty vector or CEACAM1/y− was comparable to that of empty-vector transfected HDMECs and did not change significantly (Figure 4B).

Increased podoplanin expression in endothelial cells by CEACAM1 overexpression. (A) As demonstrated by these FACS scan studies the transfection of HDMECs for CEACAM1 (CC1) and CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−) was efficient (top). Remarkably, there is a significantly higher amount of podoplanin in HDMECs overexpressing CEACAM1 (CC1), while no change is detectable in HDMECs transfected with empty vector (Evec) or CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−). The level of VEGFR-3 is enhanced only by CEACAM1 overexpression (CC1). No alteration is observed in the expression level of CD31 used as control. (B) The quantification of these repeatedly reproduced data show clearly that full-length CEACAM1 induces a significant up-regulation of podoplanin but not mutated CEACAM1/y−. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Increased podoplanin expression in endothelial cells by CEACAM1 overexpression. (A) As demonstrated by these FACS scan studies the transfection of HDMECs for CEACAM1 (CC1) and CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−) was efficient (top). Remarkably, there is a significantly higher amount of podoplanin in HDMECs overexpressing CEACAM1 (CC1), while no change is detectable in HDMECs transfected with empty vector (Evec) or CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−). The level of VEGFR-3 is enhanced only by CEACAM1 overexpression (CC1). No alteration is observed in the expression level of CD31 used as control. (B) The quantification of these repeatedly reproduced data show clearly that full-length CEACAM1 induces a significant up-regulation of podoplanin but not mutated CEACAM1/y−. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

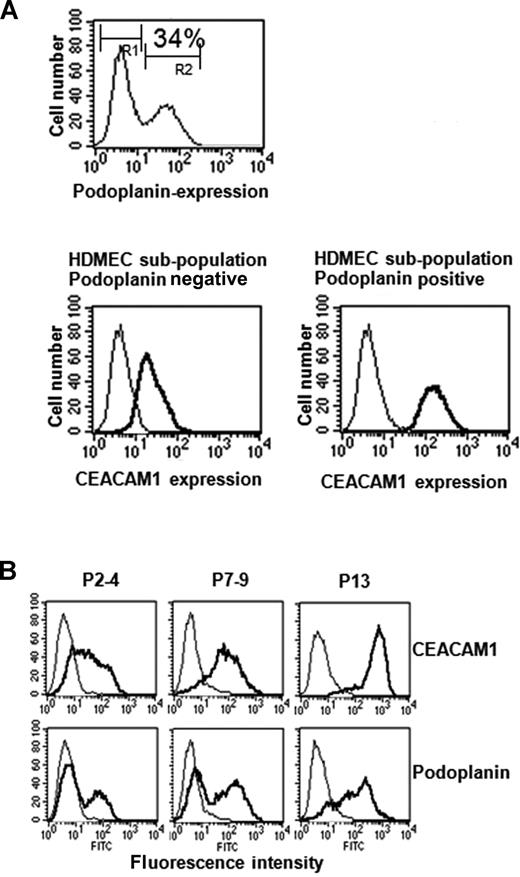

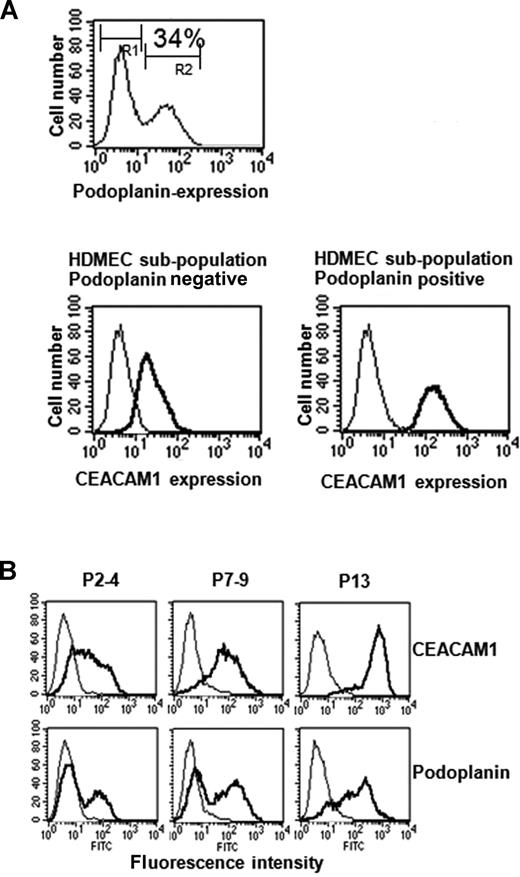

Next, we performed FACS scan of wild-type HDMECs double stained for podoplanin (FITC-channel) and CEACAM1 (PE-channel) to characterize both surface markers and their co-expression in more detail. In the representative case presented here, 34% of HDMECs stained positive for CEACAM1. Interestingly, all podoplanin-negative HDMECs expressed far less CEACAM1 (relative fluorescence, median 23) than podoplanin-positive cells (relative fluorescence, median 144; Figure 5A). The analyses raised the question of which one of the 2 factors was expressed earlier when the HDMECs were held in culture for a long period. Cultured wild-type HDMECs were analyzed by FACS at passages 3, 7, and 13 for the expression of both CEACAM1 and podoplanin. The following data have been obtained by these analyses: in P3 nearly all cells exhibited weak staining for CEACAM1, while only 10% to 30% of the HDMECs were positive for podoplanin (Figures 4A,5B). In P7, all HDMECs were highly positive for CEACAM1, but still only 20% to 40% of the cells were positive for podoplanin (Figure 5B). In P13, all cells were highly positive for CEACAM1, and now almost all HDMECs were also positive for podoplanin (Figure 5B). However, 9% to 13% of the HDMECs still stained low, and 20% to 25% stained median positive for podoplanin (Figure 5B). These results indicate that the percentage of CEACAM1-positive cells increases earlier and faster than that of podoplanin-positive HDMECs. Interestingly, using the flow cytometry approach, we found that VECs and LECs solely express CEACAM1 but no further member of the CEACAM gene family (not shown). Since FACS scan analyses did not lead to results for LYVE-1 and a further well-accepted lympangiogenic marker, Prox1, which is localized intracellular, we performed immunocytochemistry for these factors. These analyses revealed that CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs show a stronger staining for Prox1 and LYVE-1 in comparison to the corresponding empty-vector transfected HDMECs (Figure S2).

Endogenous relation between CEACAM1 and podoplanin expression in HDMECs. (A) These FACS scan studies show that 34% of HDMECs express podoplanin endogenously, indicating their lymphendothelial phenotype (top). Interestingly, double labeling of HDMECs with CEACAM1 and podoplanin show that CEACAM1 is detectable in both podoplanin-positive and podoplanin-negative HDMECs (bottom), but podoplanin-positive HDMECs express it in a higher amount. Endogenous expression of CEACAM1 in HDMECs increases during culture period. R1 indicates the cell fraction negative for podoplanin; and R2, the cell fraction positive for podoplanin. (B) At the culture passage 7-9 (P7-9), almost all HDMECs are positive for CEACAM1 (top) and reach the highest level of CEACAM1 expression at passage 13 (P13) while a great part of HDMECs at passage 7-9 (P7-9) is still negative for podoplanin, and almost all HDMECs are positive for podoplanin first at passage 13 (P13).

Endogenous relation between CEACAM1 and podoplanin expression in HDMECs. (A) These FACS scan studies show that 34% of HDMECs express podoplanin endogenously, indicating their lymphendothelial phenotype (top). Interestingly, double labeling of HDMECs with CEACAM1 and podoplanin show that CEACAM1 is detectable in both podoplanin-positive and podoplanin-negative HDMECs (bottom), but podoplanin-positive HDMECs express it in a higher amount. Endogenous expression of CEACAM1 in HDMECs increases during culture period. R1 indicates the cell fraction negative for podoplanin; and R2, the cell fraction positive for podoplanin. (B) At the culture passage 7-9 (P7-9), almost all HDMECs are positive for CEACAM1 (top) and reach the highest level of CEACAM1 expression at passage 13 (P13) while a great part of HDMECs at passage 7-9 (P7-9) is still negative for podoplanin, and almost all HDMECs are positive for podoplanin first at passage 13 (P13).

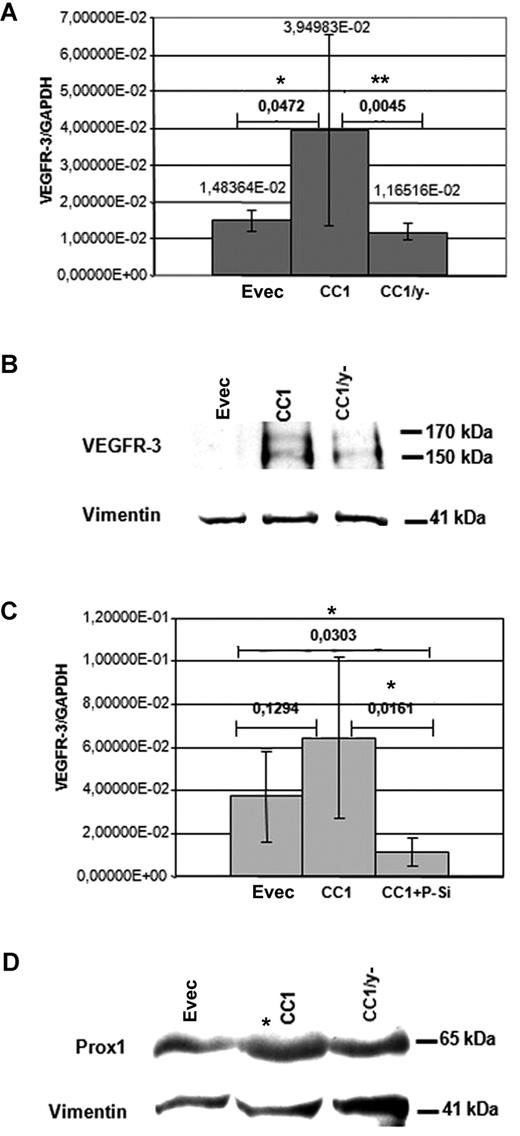

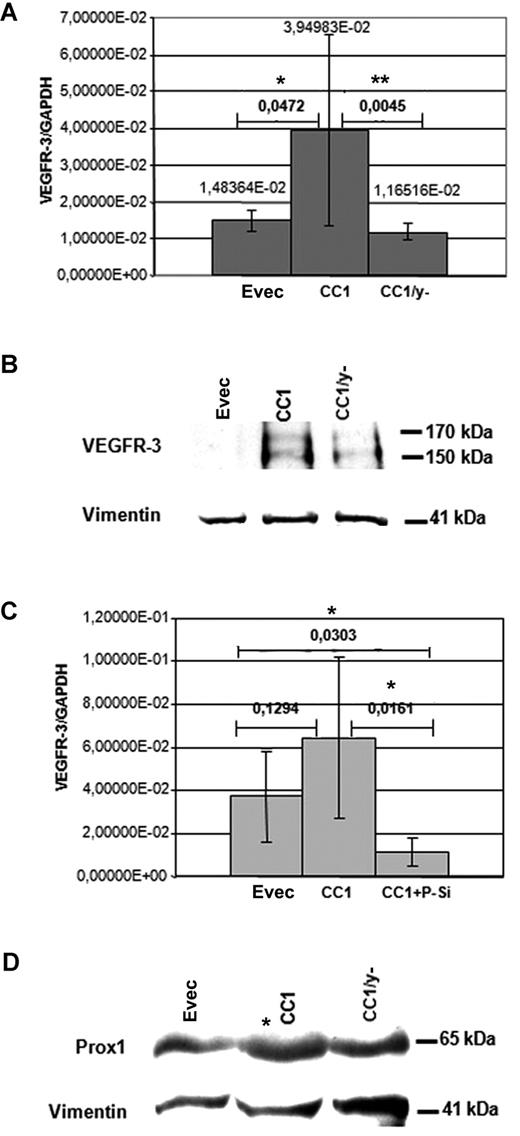

Regulation of VEGFR-3 expression by interaction between CEACAM1 and the transcription factor Prox1

To get further insight into the mechanisms of CEACAM1 effects on VEGFR-3 expression, we analyzed the effect of the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1. CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs showed a significant up-regulation of the VEGFR-3 expression, as determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR analyses. In contrast, the VEGFR-3 expression level in HDMECs transfected with CEACAM1/y− was significantly decreased and also slightly below that of the HDMECs transfected with empty vector (Figure 6A). At the protein level, as shown by immunoblotting, the amount of VEGFR-3 in CEACAM1 overexpressing HDMECs was significantly higher than that in CEACAM1/Y− overexpressing HDMECs (Figure 6B). However, in these analyses VEGFR-3 protein was not detectable in empty-vector transfected HDMECs and only slightly present in HDMECs transfected with CEACAM1/y− (Figure 6B), indicating a low level of endogenous expression of VEGFR-3 in these cells. Vimentin detection, used as control, showed equal protein loading. In a further step we asked whether Prox1, a transcription factor expressed in LECs, influences the CEACAM1-induced expression of VEGFR-3. Parallel transfection of HDMECs with CEACAM1 expression vector and with the Prox1-siRNA resulted in an approximately 6-fold effective suppres-sion of VEGFR-3 expression in comparison to that observed in HDMECs transfected only for CEACAM1 (Figure 6C). Interestingly, the transfection of HDMECs with CEACAM1 resulted in enhanced protein amount of Prox1 (Figure 6D) but not that with CEACAM1/y−.

CEACAM1 interaction with VEGFR-3 and Prox1. (A) In quantitative RT-PCR analyses, the mRNA level of VEGFR-3 is significantly elevated in CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs (CC1) in comparison to those transfected only with empty vector (EVec) and to those transfected for mutated CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−). The significance was determined applying the Student t test. (B) At the protein level, CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs (CC1) exhibit markedly enhanced amount of VEGFR-3 in comparison to HDMECs transfected for CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−) or empty vector. (C) Interestingly, the CEACAM1-induced (CC1) increase of VEGFR-3 expression in real-time RT-PCR analyses is suppressed significantly by simultaneous transfection of HDMECs for CEACAM1 and Prox1 (CC1 + P-Si) and reduced below the level of control HDMECs transfected only with empty vector. (D) HDMECs overexpressing CEACAM1 (CC1) show enhanced protein amount of Prox1 by approximately 2.5 times in comparison to that transfected with empty vector or for CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−), as demonstrated here in immunoblotting analysis. The horizontal bars represent assessment of significance, comparing Evec with CC1 or CC1 compared with CC1/y− (A) and Evec compared with CC1 or CC1 compared with CC1 + P-Si (C). *P < 0.5; **P < .01. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

CEACAM1 interaction with VEGFR-3 and Prox1. (A) In quantitative RT-PCR analyses, the mRNA level of VEGFR-3 is significantly elevated in CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs (CC1) in comparison to those transfected only with empty vector (EVec) and to those transfected for mutated CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−). The significance was determined applying the Student t test. (B) At the protein level, CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs (CC1) exhibit markedly enhanced amount of VEGFR-3 in comparison to HDMECs transfected for CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−) or empty vector. (C) Interestingly, the CEACAM1-induced (CC1) increase of VEGFR-3 expression in real-time RT-PCR analyses is suppressed significantly by simultaneous transfection of HDMECs for CEACAM1 and Prox1 (CC1 + P-Si) and reduced below the level of control HDMECs transfected only with empty vector. (D) HDMECs overexpressing CEACAM1 (CC1) show enhanced protein amount of Prox1 by approximately 2.5 times in comparison to that transfected with empty vector or for CEACAM1/y− (CC1/y−), as demonstrated here in immunoblotting analysis. The horizontal bars represent assessment of significance, comparing Evec with CC1 or CC1 compared with CC1/y− (A) and Evec compared with CC1 or CC1 compared with CC1 + P-Si (C). *P < 0.5; **P < .01. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Discussion

The present results demonstrate, to our knowledge, for the first time that CEACAM1 is up-regulated in endothelial cells of lymphatics of early tumor stages as exemplarily shown here for testicular CIS or prostate PIN. More interestingly, in activated tumor lymphatics, CEACAM1 is apparently expressed prior to its expression in tumor vascular endothelial cells. The co-expression of CEACAM1 and the lymphatic marker podoplanin only in tumor-associated lymphatics but not in quiescent large lymphatics, which were positive only for podoplanin, indicates the expression of CEACAM1 in lymphangiogenicly activated LECs. In this regard, CEACAM1 is not a marker for the whole lymphatics but, more interestingly, for activated (eg, by tumor cells) lymphatics. Interestingly, in HDMECs the lymphendothelial fraction (podoplanin positive) did express a much higher level of CEACAM1 on the cell surface than the microvascular endothelial fraction (podoplanin negative). We further show that CEACAM1 overexpression in HDMECS in turn up-regulates potent angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors such as VEGF-C and -D as well as their receptor VEGFR-3, which are obviously necessary for CEACAM1-mediated prolongation of endothelial survival. Endothelial CEACAM1 overexpression also increases the expression of lymphatic markers such as podoplanin, LYVE-1, and Prox1. Our results demonstrate that these effects of CEACAM1 depend on presence of the tyrosine residues of its cytoplasmic domain and on the activity of the transcription factor Prox1. Since overexpression of intact CEACAM1 in HDMECs results in a significant increase of the percentage of podoplanin-positive cells, we postulate that endothelial expression of CEACAM1 activates signaling mechanisms promoting lymphatic reprogramming of VECs in addition to its recently demonstrated pro-angiogenic signaling.16 Note that the reprogramming caused by CEACAM1 was seen only in microvascular (HDMECs) but not in macrovascular endothelial cells such as HUVECs.

We previously showed that CEACAM1 is up-regulated in small tumor blood vessels and demonstrated that soluble CEACAM1 acts pro-angiogenicly and is involved in the VEGF-mediated vascular morphogenesis.9 Recently, we were able to demonstrate that CEACAM1 apparently plays a dual role in tumor angiogenesis and invasion, depending on which cell type is expressing it.17 Epithelial expression of CEACAM1, as normally found in epithelia of different organs, suppressed angiogenesis, while CEACAM1 silencing in bladder cancer cell lines RT4 and 486p resulted in angiogenic activation via up-regulation of VEGF-C and -D. Similar results have recently been obtained in studies on prostate cancer.24 This may serve as an explanation why CEACAM1 has been reported to function as a tumor suppressor, since epithelial CEACAM1 is down-regulated in several tumors such as prostate and breast cancer and colorectal tumors.17,25,,,,–30 The data presented here are in line with the findings showing increased lymph node metastasis and up-regulation of VEGF-C and -D in NCAM-deficient Rip1Tag2 transgenic mice.31

However, not only angiogenesis but also lymphangiogenesis is needed for tumor growth and metastasis, as demonstrated by several in vivo studies.5 The most relevant factors regulating the outgrowth of new lymphatics are VEGF-C and –D, which bind to their high-affinity receptor VEGFR-3 (Flt-4).3,–5,32,–34 The blockade of the signaling of this receptor resulted in a significant decrease of tumor growth by a clear suppression of outgrowth of lymphatics.35,36 Recent findings showing a potential role of CEACAM1 in lymphatics have been obtained by CEACAM1 silencing in bladder cancer cell lines RT4 and 486p, resulting in up-regulation of VEGF-C and -D17 and by significantly increased expression of CEACAM1 in vascular endothelial cells infected with the Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus, which induced a lymphatic reprogramming of these cells.37

The present data provide insights into the role of CEACAM1 in lymphangiogenesis and show that CEACAM1 is apparently detectable in LECs prior to its appearance in endothelial cells of small tumor blood vessels, as shown in several publications.9,15,16 According to previously demonstrated morphological characteristics,38 our data show CEACAM1-expressing lymph vessels, which accompany large and middle-sized blood vessels and are morphologically recognizable by their irregular-shaped and partially collapsed lumen, as well as by their wall structure constituted by only endothelial cells. Since CEACAM1 overexpression in vascular endothelial cells increases the expression of VEGF-C and -D and also the expression of their receptor, VEGFR-3, a receptor highly specific for prolymphangiogenic signaling, we assume that CEACAM1 is involved in signaling mechanisms in LECs. Thus, CEACAM1 may also promote the activity of LECs present within HDMECs, as it was shown previously that the primary culture of HDMECs also contains a fraction of LECs.39 The data obtained from our in vitro endothelial tube assay analyses support this interpretation, since CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs showed the strongest tube formation under VEGF-C stimulation, which was not seen when CEACAM1/Y− overexpressing HDMECs were used. This hypothesis is further underlined by our findings that in CEACAM1-overexpressing HDMECs, the expression of LYVE-1 and, in particular, of Prox1 is increased. Although the CEACAM1-induced signaling cascades leading to up-regulation of VEGFR-3 and Prox1 are not identified, both Prox1 and VEGFR-3 seem to be downstream targets for CEACAM1 signaling. These signaling cascades apparently depend on the tyrosine residues of the cytoplasmic CEACAM1 domain because CEACAM1/y− was not able to activate the signaling mentioned above. Since endothelial Prox1 silencing abolished the CEACAM1-induced up-regulation of VEGFR-3, Prox1 seems to be essentially involved in this signaling. Prox1 has been shown to be a master transcription factor regulating multiple signaling cascades, which are essential for the development of lymphatics and for a potential re-programming of vascular endothelial cells into a lymphatic phenotype.40,41 Endothelial cells of Prox1 knockout mice did not express VEGFR-3.8 Inversely, adenoviral overexpression of Prox1 induced the expression of VEGFR-3 and several other lymphatic markers in human vascular capillary endothelial cells.42 Our present findings also are in line with recently published results showing the effects of CEACAM1 on vascular remodeling in vivo and an abrogation of CEACAM1-induced endothelial invasiveness by substitution of Tyr488 residues.43 It has been shown that tyrosine 488 of the cytoplasmic CEACAM1 domain is required for migration and invasion of melanoma cells.19 On the other hand, it was shown that the tumor-suppressive effects of CEACAM1 in breast cancer depend on the presence of full-length cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 containing the tyrosine residues.44 However, the role of the tyrosine residues of the cytoplasmic CEACAM1 domain was not studied in endothelial cells yet. Our results suggest a potential role of them in lymphangiogenic signaling of CEACAM1 in endothelial cells, but further studies are needed to decipher the cascade exactly.

Our findings on tumor tissues show that the switch from VECs to LECs apparently takes place in a very early stage of endothelial activation, since CEACAM1 is visible in newly formed lymphatics around tissue areas or structures that contain single-tumor cells or tumor-cell groups in a preinvasive cancer stage. This interpretation is also supported by the recently published findings, showing an increase of CEACAM1 expression in VECs during the switch to a lymphatic phenotype.37 Another explanation may be that CEACAM1 is probably up-regulated in tissue-resident endothelial precursor cells (EPCs) recruited for vasculogenesis/angiogenesis, as we were able to demonstrate for vascular wall resident EPCs,45 which may then be reprogrammed into a lymphatic endothelial phenotype. Indeed, it was recently demonstrated that under proper conditions, mouse embryonic stem cells are capable to differentiate to LECs and to form lymphatic structures.46 Furthermore, it has been shown that CD45-positive circulating lymphatic progenitors contribute to de novo lymphangiogenesis.47 The hypothesis that CEACAM1 might induce a lymphatic reprogramming of EPCs to LECs needs to be verified by additional experiments.

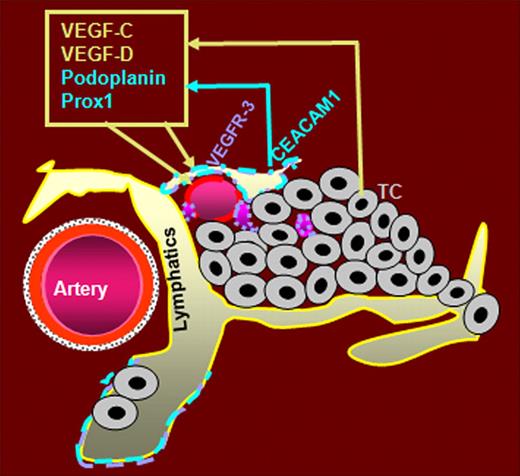

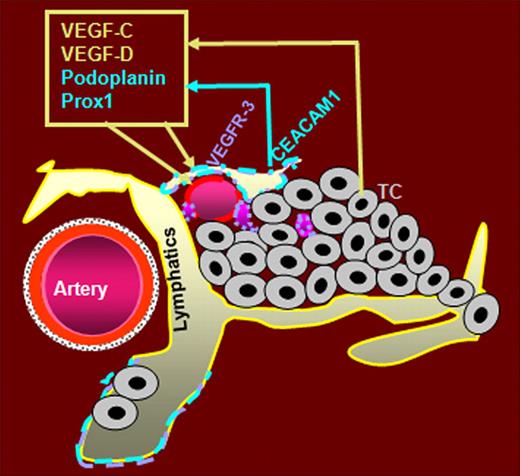

In summary, we assume that CEACAM1 plays an essential role in the early morphogenetic events of tumor lymphatics in noninvasive tumor stages. CEACAM1 might activate an autocrine loop via up-regulation of both VEGF-C and -D as well as of their receptor VEGFR-3 as summarized in the graphic (Figure 7). CEACAM1 further might promote the formation of new lymphatics by reprogramming of VECs to LECs via interaction with VEGFR-3 and the transcription factor Prox1.

Hypothetical role of CEACAM1 in tumor lymphangiogenesis. Beside the already described expression of CEACAM1 in angiogenicly activated small blood vessels, CEACAM1 is also expressed in activated LECs and apparently prior to its expression in small tumor blood vessels. We hypothesize that the up-regulation of CEACAM1 in tumor-associated lymphatics is provided by factors of the VEGF family secreted by tumor cells (TC). Endothelial CEACAM1 in turn up-regulates the expression of potent lymphangiogenic factors VEGF-C and -D and their receptor VEGFR-3, as well as the expression of lymphatic marker podoplanin and prolymphatic transcription factor Prox1. VEGF-C and -D bind to VEGFR-3, which is predominantly expressed in LECs. Thus, we assume that (1) CEACAM1 upregulation in VECs during tumor angiogenesis leads to a partial reprogramming of VECs to LECs via interaction of Prox1 and VEGFR-3, and (2) CEACAM1 up-regulation in LECs supports tumor lymphangiogenesis via an autocrine loop, leading to increased expression of prolymphangiogenic factors VEGF-C, -D, and VEGFR-3.

Hypothetical role of CEACAM1 in tumor lymphangiogenesis. Beside the already described expression of CEACAM1 in angiogenicly activated small blood vessels, CEACAM1 is also expressed in activated LECs and apparently prior to its expression in small tumor blood vessels. We hypothesize that the up-regulation of CEACAM1 in tumor-associated lymphatics is provided by factors of the VEGF family secreted by tumor cells (TC). Endothelial CEACAM1 in turn up-regulates the expression of potent lymphangiogenic factors VEGF-C and -D and their receptor VEGFR-3, as well as the expression of lymphatic marker podoplanin and prolymphatic transcription factor Prox1. VEGF-C and -D bind to VEGFR-3, which is predominantly expressed in LECs. Thus, we assume that (1) CEACAM1 upregulation in VECs during tumor angiogenesis leads to a partial reprogramming of VECs to LECs via interaction of Prox1 and VEGFR-3, and (2) CEACAM1 up-regulation in LECs supports tumor lymphangiogenesis via an autocrine loop, leading to increased expression of prolymphangiogenic factors VEGF-C, -D, and VEGFR-3.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms Kirsten Miethe and Ms Birgit Maranca-Hüwel for their excellent technical assistance. The authors are grateful to Prof C. Wagener for his advice and for supporting us with the CEACAM1-specific antibody 4D1/C2 and with cDNA for mutated CEACAM1/y−.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft as part of the Priority Program Angiogenesis, SPP1069.

Authorship

Contribution: N.K. performed research, wrote the paper, and analyzed data; L.O.-F. performed research, wrote the paper, and analyzed data; S.N.-V. performed research; K.O.-P. performed research; J.-H.W. performed research; S.L., E.K., and J.W. contributed analytical tools; H.L. analyzed data; D.T. performed research and analyzed data; B.B.S. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and S.E. designed the research and wrote the paper; and S.I. performed part of the experiments. N.K., L.O.-F., and B.B.S. contributed to this work equally.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Süleyman Ergün, Institute of Anatomy I, University Hospital Essen, Hufelandstr 55, D-45122 Essen, Germany; e-mail:sueleyman.erguen@uk-essen.de.

) integrated into the lymphatic endothelium exhibit only CEACAM1 (green fluorescence staining; Q).

) integrated into the lymphatic endothelium exhibit only CEACAM1 (green fluorescence staining; Q).