To address the mechanism by which the human globin genes are activated during erythropoiesis, we have used a tiled microarray to analyze the pattern of transcription factor binding and associated histone modifications across the telomeric region of human chromosome 16 in primary erythroid and nonerythroid cells. This 220-kb region includes the α globin genes and 9 widely expressed genes flanking the α globin locus. This un-biased, comprehensive analysis of transcription factor binding and histone modifications (acetylation and methylation) described here not only identified all known cis-acting regulatory elements in the human α globin cluster but also demonstrated that there are no additional erythroid-specific regulatory elements in the 220-kb region tested. In addition, the pattern of histone modification distinguished promoter elements from potential enhancer elements across this region. Finally, comparison of the human and mouse orthologous regions in a unique mouse model, with both regions coexpressed in the same animal, showed significant differences that may explain how these 2 clusters are regulated differently in vivo.

Introduction

Globin gene expression plays a central role in normal erythropoiesis, and abnormalities of globin synthesis underlie the clinically important thalassaemia syndromes. A long-term goal in the treatment of thalassaemia has been to identify ways in which to manipulate gene expression to redress the imbalance in α and β globin chain synthesis. Progress in this area would be enhanced by understanding in detail how these genes are normally regulated. To address this, it is important to identify all the key cis-acting sequences controlling α and β globin expression, the transcription factors that bind them, and the accompanying modifications of chromatin at different stages of differentiation.

To identify and characterize the cis-acting elements controlling α globin expression we have previously used a variety of approaches, including comparative genomics,1,2 a wide range of chromatin analyses,3,4 transgenic experiments,5,6 and the analysis of expression in interspecific hybrids.7,–9 Upstream of the 4 α-like globin promoters (ζ, αD, α2, and α1) lie 4 multispecies conserved sequences (MCSs) associated with erythroid-specific DNase1 hypersensitive sites (HS), referred to, in human, as HS-48, HS-40, HS-33, and HS-10 (Figure 1A). The globin genes, the upstream MCSs, and several widely expressed flanking genes all lie within a region of conserved synteny spanning 130 kb of the telomeric region of human chromosome 16 (16p13.3) (Figure 1A). Functional analyses suggest that HS-40 is the most important of the MCSs.9

ChIP-chip analysis of histone acetylation across 220-kb of chromosome 16p13.3. (A) Overview of the human α globin locus. The positions of erythroid-specific DNase1 hypersensitive sites (eDHSs) associated with the murine MCS elements are shown at the top. The genes located in the telomeric region of chromosome 16p are shown. The red shadow box represents the putative α globin regulatory domain exchanged between human and mouse to produce the humanized mouse model.10 The region of conserved synteny is represented as a horizontal bar. Below this, all CpG islands, DHSs, eDHS, and multispecies conserved regulatory sequences (MCS-R1-4) are shown. The human eDHS corresponding to MCS-R are labeled. (B) H4ac and H3ac in cells collected on day 8 of the second phase of culture (Day 8 Ery) and in T lymphocytes (T Ly) are shown. The y-axis represents enrichment of ChIP DNA over input DNA from 1 experiment. A very similar pattern of enrichment was seen for each biologic replicate. (All replicates are available at the website http://www.imm.ox.ac.uk/groups/mrc_molhaem/home_pages/Higgs.) The x-axis represents the α globin locus. Gray columns run from CpG islands through the array data. CpG islands not represented on the array are marked with an asterisk. V marks CpG islands which are not associated with promoters. Dashed vertical lines run from mouse eDHS through the array data.

ChIP-chip analysis of histone acetylation across 220-kb of chromosome 16p13.3. (A) Overview of the human α globin locus. The positions of erythroid-specific DNase1 hypersensitive sites (eDHSs) associated with the murine MCS elements are shown at the top. The genes located in the telomeric region of chromosome 16p are shown. The red shadow box represents the putative α globin regulatory domain exchanged between human and mouse to produce the humanized mouse model.10 The region of conserved synteny is represented as a horizontal bar. Below this, all CpG islands, DHSs, eDHS, and multispecies conserved regulatory sequences (MCS-R1-4) are shown. The human eDHS corresponding to MCS-R are labeled. (B) H4ac and H3ac in cells collected on day 8 of the second phase of culture (Day 8 Ery) and in T lymphocytes (T Ly) are shown. The y-axis represents enrichment of ChIP DNA over input DNA from 1 experiment. A very similar pattern of enrichment was seen for each biologic replicate. (All replicates are available at the website http://www.imm.ox.ac.uk/groups/mrc_molhaem/home_pages/Higgs.) The x-axis represents the α globin locus. Gray columns run from CpG islands through the array data. CpG islands not represented on the array are marked with an asterisk. V marks CpG islands which are not associated with promoters. Dashed vertical lines run from mouse eDHS through the array data.

Recently, to develop a relevant experimental system for studying human α globin expression and to evaluate the roles of individual elements, we established a humanized mouse model in which the 117-kb region containing the human α-like globin genes and all of their known regulatory elements (the α globin regulatory domain) completely replaces the corresponding, orthologous region of the mouse genome (Figure 1A).10 Although, in this model, the human α genes are expressed in an appropriate tissue-specific and developmental stage–specific manner, their level of expression is suboptimal (40% of that of the endogenous genes). This could either be because one or more critical elements in the human cluster have been overlooked in previous analyses or because changes in the structure or recognition of sequences by the key transcription factors have altered during evolution such that binding or stability of mouse transcription factors on human sequences are suboptimal. These observations prompted us to reassess the full extent of the human α globin regulatory domain and to compare, in detail, the binding of transcription factors and epigenetic modifications in the human and mouse α globin clusters during erythropoiesis.

Using a tiled microarray, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–chip technology (see “ChIP assay”), validated by ChIP-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), to assess the binding of key erythroid transcription factors and characterize the associated histone modifications at defined stages of erythropoiesis. Applying this newly established ChIP-chip technology allowed us to obtain a comprehensive, unbiased analysis of the binding and activation of potential cis-acting sequences in a contiguous 220-kb region of chromosome 16, extending 50 kb on either side of the previously defined α globin regulatory domain. This demonstrated that, within this region, no sequences other than the known upstream regulatory elements and human α globin promoters bound erythroid transcription factor complexes or became activated (as judged by relevant histone modifications) in erythroid cells. In basophilic erythroblasts, when the α globin genes are fully active, a domain of histone H4 acetylation extending through 80 kb became established. Thus, together, these findings redefine the limits of the human α globin regulatory domain.

The humanized mouse model allowed, for the first time, a direct comparison of transcription factor binding and chromatin modification, in heterozygotes, at the human and mouse loci in nuclei with identical transcriptional and epigenetic programs. Using this model, and by comparing ChIP data from primary human and mouse erythroid cells,4 we identified significant differences in transcription factor binding and histone modification at the human and mouse clusters which may explain differences in their regulation.

Finally the use of the tiled microarray allowed us to compare histone modifications across the entire α globin regulatory domain with those encompassing the 9 widely expressed flanking genes, whose epigenetic profile had not previously been studied. These epigenetic marks, in combination, distinguish promoter elements from other classes of regulatory element (eg, enhancers).

Materials and methods

Cells and cultures

K562 were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 50 U/mL penicillin G (GIBCO, Paisley, United Kingdom), 50 μg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO), and 2 mM l-glutamine (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (PAA Laboratories, Linz, Austria). Primary human erythroblasts were obtained from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected from blood donors and expanded in a 2-phase system as previously described.11,12 Primary human T lymphocytes were obtained from PBMCs by culture for 3 days in RPMI/20% fetal calf serum in the presence of 2% phytohaemagglutinin M (GIBCO) and 20 U/mL interleukin-2. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)–transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines were derived from healthy subjects. Mature primary murine erythroblasts were obtained from phenylhydrazine-treated adult “humanized” mice, as described.10

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: anti–diacetylated histone H3 (06-599), anti–tetra-acetylated histone H4 (06-866), and anti–mono-, –di- and –trimethyl Lys4 histone H3 (07-436, 07-030, and 07-473, respectively) from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY); RNA polymerase (Pol) II N20, RNA Pol II H224, NF-E2 C19, NF-E2 p18 C16, GATA2 H-116, GATA1 C20, GATA1 M20, and E2A.E12 V18 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); and stem cell leukemia (SCL),13 Ldb-1, and LMO214 (kindly provided by Dr. Catherine Porcher, Molecular Hematology Unit, Oxford, United Kingdom).

ChIP assay

ChIPs were performed according to the Upstate ChIP protocol, as described previously with minor modifications.4 Cells (1.5 × 107 per experiment) were fixed with 0.4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature and chromatin was sonicated to a size of less than 500 base pairs (bp). Immunoprecipitations were performed, after an overnight incubation with the appropriate antibody, with protein A agarose (Upstate) or with protein G agarose (Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany) when using GATA1 antibody. A sample containing no antibody was used as a negative control.

Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR (ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers and 5′FAM-3′TAMRA Taqman probes, for selected sequences of the human α globin locus (available on request), were designed by Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). All primers and probes were validated over a serial dilution of genomic DNA. For a given target sequence, the amount of product precipitated by a specific antibody was determined relative to the amount of nonimmunoprecipitated (input) DNA and these results were normalized to a control sequence in the 18S ribosomal RNA (RNRI) gene.

ChIP-chip analysis

The custom α globin tiling path microarray has been described previously.15 Four hundred fifty nanograms of ChIP DNA, obtained for each antibody from 2 independent IP reactions, and 450 ng of input DNA were labeled with Cy3–2′-deoxycytosine 5′-triphosphate (dCTP; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) and Cy5-dCTP (Amersham), respectively, with Bioprime Labeling system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Labeled DNA was purified through Amersham G50 columns. ChIP-Cy3 and input-Cy5 DNAs were combined, precipitated in ethanol with human Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen) and yeast t-RNA (Invitrogen), and resuspended in hybridization buffer (50% [vol/vol] formamide, 2× standard saline citrate [SSC], 10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 5% [wt/vol] dextran sulfate, 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20). The arrays were hybridized with the hybridization solution containing the labeled DNAs in a HS 400 Pro Hybridization Station (Tecan Austria, Groding/Salzburg, Austria) for 45 hours. The arrays were then scanned in a Scan Array Gx Plus scanner (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT) and the spot intensities were quantified using Scan Array Express Version 3.0 (Perkin Elmer) with background subtraction. The ratio of the background-corrected ChIP signal divided by the background-corrected input signal (both globally normalized) were used for the analysis. The data were then plotted and visualized on a private customized genome database designed by the Computational Biology Research Group (Oxford University). Figures 1, 3, and 5 were generated by the database.

Results

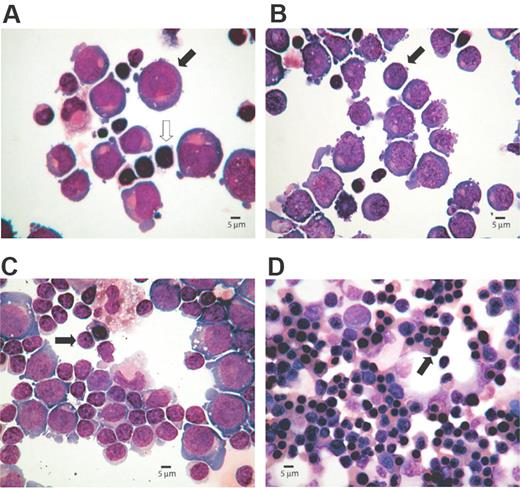

To study chromatin modifications and transcription factor binding throughout the terminal region of chromosome 16, we analyzed primary human erythroblasts together with the human erythroid cell line K562. Primary human T lymphocytes or EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines were studied as examples of differentiated, nonerythroid cells. Erythroid progenitors were derived from PBMCs cultured through a 2-phase liquid culture system. It has been previously shown11,12 that circulating erythroid progenitors differentiate into colony-forming unit (CFU)–E and terminally differentiate to erythrocytes after the addition of erythropoietin. Cell samples were collected on days 5, 8, 11, and 15 of the second phase of culture. Although heterogeneous cell populations are present at any particular stage, clear differences in maturation are distinguishable (Figure 2).

Cytospin preparations representing morphology of erythroid cells at different stages of the culture. The percentages of erythroid cells at each stage of differentiation were determined microscopically after May-Grünwald-Giemsa (MGG)–stained cytospins. Images were captured with an Olympus BX40 microscope, 40×/0.95 numerical aperture lens, fitted with Olympus Camedia C-3040ZOOM camera, and processed with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). (A) Proerythroblasts (40%,  ) are present on day 5, although lymphocytes (

) are present on day 5, although lymphocytes ( ) are the most abundant cell type. (B) Basophilic normoblasts (50%,

) are the most abundant cell type. (B) Basophilic normoblasts (50%,  ) are discernible on day 8. (C) Day 11 preparation demonstrates polychromatic erythroblasts (65%,

) are discernible on day 8. (C) Day 11 preparation demonstrates polychromatic erythroblasts (65%,  ). (D) Day 15 culture shows late erythroblasts with pycnotic and shrunken nuclei (95%,

). (D) Day 15 culture shows late erythroblasts with pycnotic and shrunken nuclei (95%,  ).

).

Cytospin preparations representing morphology of erythroid cells at different stages of the culture. The percentages of erythroid cells at each stage of differentiation were determined microscopically after May-Grünwald-Giemsa (MGG)–stained cytospins. Images were captured with an Olympus BX40 microscope, 40×/0.95 numerical aperture lens, fitted with Olympus Camedia C-3040ZOOM camera, and processed with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). (A) Proerythroblasts (40%,  ) are present on day 5, although lymphocytes (

) are present on day 5, although lymphocytes ( ) are the most abundant cell type. (B) Basophilic normoblasts (50%,

) are the most abundant cell type. (B) Basophilic normoblasts (50%,  ) are discernible on day 8. (C) Day 11 preparation demonstrates polychromatic erythroblasts (65%,

) are discernible on day 8. (C) Day 11 preparation demonstrates polychromatic erythroblasts (65%,  ). (D) Day 15 culture shows late erythroblasts with pycnotic and shrunken nuclei (95%,

). (D) Day 15 culture shows late erythroblasts with pycnotic and shrunken nuclei (95%,  ).

).

The pattern of histone acetylation across the terminal 220 kb of human chromosome 16

Using a ChIP-chip approach, the pattern of histone H3 and H4 acetylation (H3ac and H4ac) was determined across a 220-kb, telomeric region of human chromosome 16, including the putative α globin regulatory domain. For each modification we performed 2 biologic ChIP-chip replicates using primary human basophilic erythroblasts (obtained at day 8 of culture; Figure 2B) and T lymphocytes. These duplicate analyses provided very similar profiles (data available for comparison at http://www.imm.ox.ac.uk/groups/mrc_molhaem/home_pages/Higgs).

By analyzing chromatin from lymphocytes (Figure 1B) we detected relatively small peaks of H3 and H4 acetylation at the CpG islands associated with the promoters of the widely expressed genes that flank the α globin cluster. As previously noted,3 there were very low levels of H3ac and H4ac throughout the inactive α globin regulatory domain. In primary adult erythroblasts (Figure 1B),H3ac was enriched at the CpG islands associated with the promoters of the expressed α globin genes (αD, α2, and α1), and to a lesser extent at the ζ and θ globin genes, which are also associated with CpG islands. Low levels of H3ac were also seen at all upstream MCS elements (HS-48, HS-40, HS-33, and HS-10). By contrast, H4ac appeared more uniformly enriched at both the upstream elements and the active globin gene promoters in erythroid cells.

To validate these ChIP-chip data and to extend the analysis throughout erythroid differentiation, we carried out independent, duplicate ChIP-qPCR analyses in primary human erythroblasts at each stage of maturation, in T lymphocytes, and in the K562 cell line. The levels of H4ac and H3ac changed relatively little during erythroid differentiation (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) but appeared to reach a maximum in basophilic erythroblasts (day 8; Figure 2B) and subsequently decrease. The lower levels of enrichment in the earliest stages of erythropoiesis could reflect the greater cellular heterogeneity in these populations. The pattern of acetylation observed in K562 (Figure S1) was similar to that seen in primary erythroblasts, although an additional peak of acetylation was seen around the embryonic ζ globin gene, which is expressed in these cells. Moreover, in K562 the level of histone acetylation detected at HS-10 was greater than in primary erythroblasts, suggesting a potential role for this element in the regulation of embryonic gene expression.

In summary, the domain of histone acetylation that appears in human erythroid cells extends from coordinates 92 000 to 172 000 and peaks of acetylation were seen only at previously characterized erythroid MCS elements and promoters. This comprehensive and extensive analysis thus provides important confirmation of the previously defined limits of the human α globin regulatory domain and established that there are no additional elements that may have been overlooked in the 220-kb region studied.

The pattern of transcription factor and RNA Polymerase II binding across the terminal 220 kb of human chromosome 16

We next determined whether the activated promoters and MCS elements in the human α globin cluster bound the same or similar repertoires of erythroid transcription factors in vivo as previously described for the mouse α globin cluster. We therefore performed ChIP-chip experiments for GATA1, SCL, and NF-E2 in day 8 basophilic erythroblasts (Figure 3) and ChIP-qPCR analysis for GATA2. No GATA2 binding was detected (data not shown), reflecting the fact that our analysis focused on the later steps of erythroid differentiation when GATA1 expression has largely replaced GATA2. As in the mouse cluster, the 4 upstream MCS elements (HS-48, HS-40, HS-33, and HS-10) all bind GATA1, SCL (Figure 3), and the entire pentameric erythroid complex (data not shown) which includes GATA1, SCL, E2A, Lim-only 2 (LMO2), and LIM domain binding protein 1 (Ldb1). This complex is thought to play an important role in the positive regulation of erythroid-specific genes.16,–18 In addition, enrichment of both p45 and p18 NF-E2 subunits were observed at HS-40, and to a lesser extent, at HS-48. However, unlike the mouse α globin locus, no GATA1 binding was detected at the human α globin promoters. Furthermore, consistent with the lack of any DNase1 HS (D.R.H. and M.D.G., unpublished data, March 2004) and lack of histone modification (Figure 1B), no transcription factor binding (GATA1, SCL, and NF-E2) was found in the orthologous region corresponding to the mouse HS-12 element (hoHS-12). This approximately 250-bp region of the human genome (coordinates Human build HG18 chr16:125635–125878) aligned maximally with the region corresponding to mouse HS-12, as defined by a multispecies aligment,2 and is 53% homologous to the mouse region. However, unlike other MCS elements it contains no highly conserved transcription factor binding sites and, in particular, no consensus GATA1 binding site. No further erythroid transcription factor binding was identified across the 220-kb region analyzed, confirming that no additional erythroid-specific regulatory elements were present in this region.

ChIP-chip analysis of transcription factors and PolII across 220 kb of chromosome 16p13.3. Binding profile of GATA1 in primary erythroblasts from a homozygote “humanized” mouse (HM Ery) and of SCL, NF-E2 p45, NF-E2 p18, and PolII in day 8 human erythroblasts (Day 8 Ery) are shown. A schematic representation of the α globin locus is shown at the top annotated as in Figure 1. Note that the binding profile of GATA1 is derived from “humanized” mouse because antibodies recognizing human GATA1 do not perform well in ChIP assay.

ChIP-chip analysis of transcription factors and PolII across 220 kb of chromosome 16p13.3. Binding profile of GATA1 in primary erythroblasts from a homozygote “humanized” mouse (HM Ery) and of SCL, NF-E2 p45, NF-E2 p18, and PolII in day 8 human erythroblasts (Day 8 Ery) are shown. A schematic representation of the α globin locus is shown at the top annotated as in Figure 1. Note that the binding profile of GATA1 is derived from “humanized” mouse because antibodies recognizing human GATA1 do not perform well in ChIP assay.

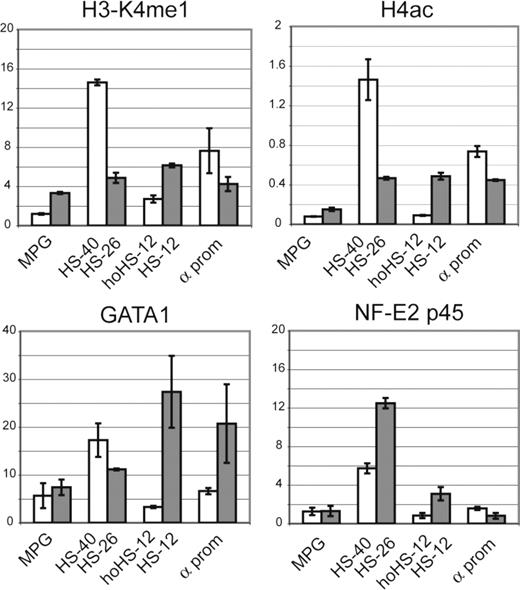

We also examined chromatin structure in the heterozygote humanized mouse model. In this model, the human and mouse α globin loci lie in the same nucleus and share an identical murine transcription factor environment. ChIP-qPCR analysis was performed in mature erythroid cells (Ter119+) isolated from the spleen of a phenylhydrazine-treated mouse. Using H4ac and H3K4me1 (see “Analysis of histone methylation”) antibodies, it was shown that unlike hoHS-12, which had only a basal level of histone acetylation and methylation (as judged by comparison with a nonregulatory sequence, MPG in Figure 4), HS-12 in mouse was modified as active chromatin. Consistent with this observation, analysis of transcription factor binding showed that whereas GATA1 and NF-E2 bound the HS-12 element in the mouse chromosome, no binding was seen at the corresponding region on the humanized chromosome (Figure 4). This shows that, even in the mouse background, there is no “cryptic” binding site at hoHS-12. We then tested the effect of the mouse transcription factor environment on GATA1 recruitment at human α globin promoters. As seen in primary human erythroblasts (Figure S2), no GATA1 binding was detected at the human α globin promoters in this model (Figure 4).

ChIP-qPCR analysis in humanized mouse erythroid cells. H3K4me1, H4ac, GATA1, and NF-E2 p45 ChIP-qPCR analysis in Ter119+ cells isolated from heterozygote humanized mouse. The y-axis represents average enrichment over input DNA from independent ChIPs, normalized to a mouse GAPDH control sequence. Error bars correspond to 1 (± SD) from at least 2 independent ChIPs. Human amplicons ( ) and mouse amplicons (

) and mouse amplicons ( ) are indicated on the x-axis. MPG indicates intronic sequence in MPG gene; α prom, α globin promoter sequence.

) are indicated on the x-axis. MPG indicates intronic sequence in MPG gene; α prom, α globin promoter sequence.

ChIP-qPCR analysis in humanized mouse erythroid cells. H3K4me1, H4ac, GATA1, and NF-E2 p45 ChIP-qPCR analysis in Ter119+ cells isolated from heterozygote humanized mouse. The y-axis represents average enrichment over input DNA from independent ChIPs, normalized to a mouse GAPDH control sequence. Error bars correspond to 1 (± SD) from at least 2 independent ChIPs. Human amplicons ( ) and mouse amplicons (

) and mouse amplicons ( ) are indicated on the x-axis. MPG indicates intronic sequence in MPG gene; α prom, α globin promoter sequence.

) are indicated on the x-axis. MPG indicates intronic sequence in MPG gene; α prom, α globin promoter sequence.

Next, we mapped RNA Polymerase II (PolII) binding throughout the terminal region of human chromosome 16 (Figure 3). ChIP-chip analysis using anti-PolII antibody showed the binding of PolII to the α globin promoters and to the regulatory elements HS-48 and HS-40, consistent with previous data from the mouse locus demonstrating the recruitment of PolII at these upstream elements during terminal erythroid differentiation. Although no binding was seen at HS-33 and HS-10 in the ChIP on chip analysis, these elements do bind PolII as judged by qPCR (Figure S2).

Using ChIP-qPCR, we characterized the temporal association of transcription factors and PolII within the locus during erythroblast maturation (Figure S2). The maximal enrichment of GATA1, SCL, and NF-E2 occurred in the intermediate stages of maturation (basophilic and polychromatic erythroblasts). At the later stages of erythropoiesis, GATA1 and SCL were no longer binding, whereas NF-E2 was still detectable at very low levels. An identical pattern of GATA1 and SCL complex (Ldb1, LMO2, and E2A) binding was found in K562 cells (Figure S3). Finally, PolII was shown to be bound at the α globin promoter in human erythroid cells from the first recognized stages of erythropoiesis and had a maximum recruitment after 8 to 11 days of second phase culture when a low enrichment was found at all the remote conserved elements (HS-48, HS-40, HS-33, and HS-10).

Analysis of histone methylation

Recent evidence suggests that cis-acting elements may not only be identified but may also be classified on the basis of the associated histone modifications, giving some insight into the role of individual elements. In fact, ChIP-chip analysis of 1% of human genome19 showed that, whereas most promoters of active genes are enriched in H3K4me3, enhancers appear to be marked by H3K4me1. Therefore, in addition to analyzing the patterns of histone acetylation, we also investigated the patterns of H3K4 mono-, di-, and trimethylation across the 220-kb region of human chromosome 16 (Figure 5).

ChIP-chip analysis of H3K4 methylation across 220 kb of chromosome 16p13.3. H3K4me1, -me2, and -me3 in cells collected on day 8 of the second phase of culture (Day 8 Ery) and in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (EBV-Ly) are shown. The y-axis represents enrichment of ChIP DNA over input DNA from one experiment. A very similar pattern of enrichment was seen for each biologic replicate. All replicates are available at the following website: http://www.imm.ox.ac.uk/groups/mrc_molhaem/home_pages/Higgs. A schematic representation of the α globin locus is shown at the top and annotated as in Figure 1.

ChIP-chip analysis of H3K4 methylation across 220 kb of chromosome 16p13.3. H3K4me1, -me2, and -me3 in cells collected on day 8 of the second phase of culture (Day 8 Ery) and in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (EBV-Ly) are shown. The y-axis represents enrichment of ChIP DNA over input DNA from one experiment. A very similar pattern of enrichment was seen for each biologic replicate. All replicates are available at the following website: http://www.imm.ox.ac.uk/groups/mrc_molhaem/home_pages/Higgs. A schematic representation of the α globin locus is shown at the top and annotated as in Figure 1.

In erythroid cells, the H3K4me1 modification was found at the upstream MCS elements and equally enriched at the promoters of the globin genes. No significant enrichment of H3K4me1 was seen at the upstream MCSs in nonerythroid cells, whereas it was slightly enriched at all the promoters (globin and nonglobin). H3K4me2-modified histones were clearly present at all promoters but not at upstream regulatory elements in nonerythroid cells. In erythroid cells H3K4me2 was readily detectable at the upstream elements and was further enriched at the globin promoters. H3K4me3 was enriched at the promoters of nonglobin genes in nonerythroid cells and became, in comparison with the surrounding promoters, significantly enriched at the globin promoters only in erythroid cells. The level of H3K4 methylation changed relatively little during erythroid differentiation (data not shown). Therefore, consistent with a global analysis of these modifications,19 H3K4me1 appears to be equally enriched at enhancer and promoter regions whereas H3K4me3 is more highly enriched at active promoters than enhancers in cells where these genes are expressed.

Discussion

Superficially, the transcriptional and epigenetic programs controlling basic biologic processes (eg erythropoiesis) appear very similar comparing one mammalian species with another and the proteins involved are often conserved. When considering hemopoiesis, comparisons are also frequently extended and drawn between mammals, amphibians, and fish. However, there is increasing evidence that the detailed mechanisms by which each species achieves fully regulated expression of a given gene in the context of its own transcriptional/epigenetic program may be quite different.20,–22 In this case, simple extrapolation of mechanisms established in one species might be misleading when considering another.

Here we have confronted this general issue by asking if the human and mouse α globin clusters are regulated in the same or different ways. To fully address this point we first needed to be sure that we have identified all of the sequences required for fully regulated expression of the human α cluster in the context of its own transcriptional/epigenetic program. Here we used a newly developed tiling array to comprehensively analyze the patterns of transcription factor binding and histone modifications across a region of 220 kb of human chromosome 16 (extending 50 kb either side of the currently defined domain). Based on this study we can conclude that there appear to be no additional erythroid cis-elements in this region although we cannot formally rule out even more distant regulatory elements. Therefore, it seems most likely that the previously reported, suboptimal expression of the human α gene cluster (containing all known regulatory elements) in the mouse10 results from altered interactions, deriving from species-specific differences between the mouse transcription factors/cofactors and the human cis-acting elements. In this case, fully equivalent expression of the wild-type, human α globin cluster in a mouse transcription/epigenetic environment may not be achievable.

Clearly evolution has ensured that each cluster is expressed optimally within its own environment. But has this process “tinkered” with the same set of orthologous cis-elements, have new elements been recruited, and have others become redundant? Evidence from other systems would suggest that all of these processes may be in operation.22 Using sequence comparisons between erythroid cis-elements (marked by erythroid-specific DNase1 HSs) in the human and mouse α globin clusters there are clearly 5 conserved orthologous sequences (excluding hoHS-12, Table 1). However, these conserved regulatory elements appear to play different roles in each cluster. For example, removal of HS-40 alone from the human α globin cluster leads to a severe reduction (< 5%) in PolII recruitment and α gene expression, whereas removal of the orthologous element (HS-26) in mouse causes only a moderate (∼50%) decrease in expression.23 It seems that another element (or elements) must normally contribute significant levels of α globin expression in the mouse. A comparison of transcription factor binding in orthologous, conserved noncoding sequences in mouse and human is shown in Table 1. This highlights 2 significant differences. First, whereas the mouse α globin promoter includes a consensus GATA sequence that is bound by GATA1 (and its cofactor ZBP; Dr. Douglas Vernimmen, unpublished data, April 2007) in vivo, the human α globin promoter does not. In fact, the α globin promoter, compared in multiple, diverse mammalian species, does not contain an evolutionarily conserved GATA site. Second, hoHS-12 is not marked by DNase1 HS and contains no conserved transcription factor binding sites corresponding to those at the mouse cis-element HS-12 (Figure 1A). In mouse erythroid cells, this element (like HS-40 and HS-48 in human) binds both the pentameric erythroid complex (GATA1, SCL, E2A, LMO2, and Ldb-1) and NF-E2 and becomes activated (as judged by histone acetylation) during erythropoiesis. No corresponding transcription factor binding or chromatin activation was seen in the human, even in a mouse erythroid cell background (Figure 4). These observations show that the human and mouse clusters achieve fully regulated expression in somewhat different ways. Not only do the orthologous sequences play different roles in these 2 species but an additional, species-specific element (HS-12) appears to have been recruited in the mouse cluster. Nevertheless, further studies will be required to define the precise role of this new element in vivo.

Knowing which transcription factors bind each conserved sequence may help determine the role each sequence plays in regulating α globin expression. In human, natural deletions associated with α thalassaemia (which all delete HS-48 and HS-40) show that HS-33 and HS-10 alone are not able to drive α globin expression whereas either HS-40, with or without HS-48, is essential.24 This might be related to the fact that HS-33 and HS-10 bind only the GATA1/SCL complex whereas HS-48 and HS-40 bind both this complex and NF-E2 (Table 1). Previous experiments on the β globin locus control region elements have suggested that GATA1 may be required to recruit PolII to such elements, but PolII is then transferred to the promoter in an NF-E2–dependent manner.25,26 Thus when HS-40 and HS-48 are deleted, PolII might be recruited to the remaining upstream elements (HS-33 and HS-1027) but not transferred to the α globin promoters. Although the mechanism of transfer is unknown it seems most likely to involve physical interaction between the upstream elements and the promoters.27 It is interesting to note that the additional recruited element in mouse (HS-12), which, together with HS-26, may subsume the role of HS-40 in human, also binds NF-E2.

The different patterns of histone modification found at the upstream elements and the α globin promoters may add to the previously proposed model describing how the upstream elements enhance α globin transcription.27 Here, and elsewhere,3 we have shown that acetylation of histone H4 is equally strong at the upstream elements and the promoters in erythroid cells. This could be explained by the recruitment of histone acetylases by specific and general DNA binding transcription factors at all cis-acting elements. By contrast, acetylation of histone H3 is much less prominent at the upstream elements than at the promoters. Interestingly, monomethylation of histone H3K4 (catalyzed by SET7/9 histone methyltransferase28,29 ) is equally enriched at the upstream elements and the promoters in erythroid cells. H3K4me2 (catalyzed by Set1-like family of histone methyltransferases) is more prominent at the promoters, and H3K4me3 (also catalyzed by Set1-like complexes30,–32 ) is still further enriched at the promoters compared with the upstream elements. It has previously been shown that patterns of histone H3K4 methylation may be influenced by the state of the associated PolII.33,34 In yeast, Set1 is recruited to chromatin only when the C-terminal domain of PolII is phosphorylated at serine 5 (ie when activated for initiation of transcription).35 In human, MLL1, homologous to yeast Set1, colocalizes with PolII to the 5′ end of actively transcribed genes.36 This suggests that the PolII recruited at the upstream elements might be inactive (and possibly not even engaged with DNA) and therefore the associated histones are predominantly modified with H3K4me1. By contrast, the PolII at the promoters is engaged and activated and in a state to recruit Set1-like proteins; thus, the associated histones are modified with H3K4me2 and H3K4me3. This implies that PolII may be initially recruited to the upstream elements in an inactive form and then transferred to the promoters where activation takes place.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated how the use of a genomic microarray to study in vivo chromatin modifications may help explain some aspects of gene regulation at a specific locus. In addition, it has highlighted some differences in the mechanism of human and mouse α globin regulation which impose important caveats when using the mouse as a model to study human gene regulation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) and National Human Genome Research Institute grant U01HG003168 (I.D.) and the Wellcome Trust. M.D.G. is a PhD student in Pharmacology and Clinical and Experimental Therapy at Turin University, Italy.

We would like to thank the Computational Biology Research Group (Oxford University), Gayle Clelland, and Sarah Wilcox for the technical assistance, Cordelia Langford, Peter Ellis, and the staff of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Microarray Facility for array printing, Catherine Porcher for SCL complex antibodies, and Doug Vernimmen for advice and comments on the manuscript.

Wellcome Trust

Authorship

Contribution: M.DG., E.A., I.D., R.J.G., W.G.W., and D.R.H designed research; M.DG., J.A.S-S., and J.A.S performed experiments; M.DG, E.A., J.H., and C.M.K. analyzed data; and M.DG., R.J.G., W.G.W, and D.R.H. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Doug Higgs, Medical Research Council Molecular Haematology Unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Oxford University, Oxford, OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; e-mail:doug.higgs@imm.ox.ac.uk.