Abstract

Mast cells may be activated through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) for the dose- and time-dependent release of eicosanoids. However, the signaling mechanisms of TLR-dependent rapid eicosanoid generation are not known. We previously reported a role for group V secretory phospholipase A2 (PLA2) in regulating phagocytosis of zymosan and the ensuing eicosanoid generation in mouse resident peritoneal macrophages, suggesting a role for the enzyme in innate immunity. In the present study, we have used gene knockout mice to define an essential role for MyD88 and cytosolic PLA2α in TLR2-dependent eicosanoid generation. Furthermore, in mast cells lacking group V secretory PLA2, the time course of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and of cPLA2α was markedly truncated, leading to attenuation of eicosanoid generation in response to stimulation through TLR2, but not through c-kit or FcεRI. These findings provide the first dissection of the mechanisms of TLR-dependent rapid eicosanoid generation, which is MyD88-dependent, requires cPLA2α, and is amplified by group V sPLA2 through its regulation of the sequential phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2 and cPLA2α. The findings support the suggestion that group V sPLA2 regulates innate immune responses.

Introduction

Mast cells, in addition to their role as central effector cells of allergic disease and various autoimmune and inflammatory processes, are important sensors of invading pathogens.1,2 The latter function is mediated through pattern recognition receptors that include CD483 and the Toll-like receptors.4-6 Engagement of TLRs on human and mouse mast cells leads to robust generation of cytokines and chemokines.4-11 However, there are limited data on the generation of eicosanoids by mast cells in response to TLR signaling, and there has been no dissection of its mechanism

Eicosanoids are generated from the polyunsaturated fatty acid, arachidonic acid, which is released from the sn-2 position of cell membrane phospholipids by one of the isoforms of phospholipase A2 (PLA2). There are 4 main classes of PLA2, group IV cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), secretory PLA2 (sPLA2), group VI calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), and the acetyl hydrolases of platelet activating factor (groups VII and VIII).12 Mice in which the gene for cPLA2α was disrupted were used to demonstrate its essential function in supplying arachidonic acid for eicosanoid biosynthesis in response to a wide range of stimuli.13,14 This leads to attenuation of allergic pulmonary inflammation,14 acute lung injury in response to acid aspiration,15 cerebral infarction following ischemia/reperfusion injury,13 and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis,16 as well as difficulties with fertilization and parturition.14 The role of sPLA2 enzymes in eicosanoid generation has been inferred from transfection studies in which sPLA2 enzymes have been overexpressed and from studies using inhibitors of poor specificity. However, the natural role of the endogenous sPLA2 enzymes has remained unclear. To explore the role of endogenous group V sPLA2, we generated mice in which the gene was disrupted by homologous recombination. We previously reported that group V sPLA2 regulates the phagocytosis of the yeast cell particle, zymosan,17 and amplifies zymosan-induced eicosanoid generation from mouse resident peritoneal macrophages,18 suggesting a role for this enzyme in innate immune responses.

We now demonstrate that TLR2-dependent LTC4 and PGD2 generation is attenuated in bone marrow–derived mast cells (BMMCs) lacking group V sPLA2, further supporting a role for this enzyme in innate immunity. We show that TLR2-dependent eicosanoid generation by mouse BMMCs requires cPLA2α and that this is a MyD88-dependent process. Group V sPLA2 amplifies the essential function of cPLA2α by regulating ERK-dependent cPLA2α phosphorylation in response to TLR2 stimulation.

Materials and methods

Materials

The study was approved by the Dana-Farber Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 01-053, Group V Phospholipase A2 and Pulmonary Inflammation).

The following reagents were purchased: the synthetic lipopeptide, S-(2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(2-RS)-propyl)-N-palmitoyl-(R)-Cys-(S)-Ser-(S)-Lys4 (Pam3CSK4) (Invivogen, San Diego, CA); peptidoglycan (PGN) from Staphylococcus aureus (Sigma, St Louis, MO); the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor, UO126 (Promega, Madison, WI); rabbit polyclonal antibodies that detect activating phosphorylations of extracellular signal-related kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 (Thr202/Tyr204), p-38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), and cPLA2α (Ser505) as well as the individual total proteins themselves (Cell signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); and recombinant mouse SCF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Recombinant mouse IL-10 was expressed in baculovirus and its concentration was determined as described.19

Transgenic mice

Mice heterozygous for disruption of the gene encoding group V sPLA2(Pla2g5)18 were crossed for 11 generations to a BALB/cJ background. Mating pairs of Pla2g5-null and wild-type mice were derived from the litters of N11 BALB/cJ heterozygous breeding pairs. Tlr2-null20 and Myd88-null mice21 were provided by Dr S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). A homogenous population was established by backcrossing to C57BL/6 mice for more than 10 generations. Mice with disruption of the gene encoding group IV cPLA2α (Pla2g4a)13 were backcrossed to BALB/cJ mice for more than 10 generations.

Culture and activation of BMMCs

Mouse bone marrow cells were cultured in 50% enriched medium (RPMI 1640 containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 10 μg/mL gentamicin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acid, and 10% FBS)/50% WEHI-3 cell (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) conditioned medium as described.19 After 4 weeks, more than 99% of cells were BMMCs with characteristic metachromatic mast cell granules as assessed by staining with toluidine blue.

For TLR2-dependent mediator release, BMMCs were washed and resuspended at 106 cells per 500 μL culture medium and incubated with increasing doses of Pam3CSK4 for various periods. The reaction was stopped by centrifugation of the cells at 120g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants were retained for assay of mediator release. In selected experiments, BMMCs were cultured for 2 days in 50% WEHI-3 cell–conditioned medium containing 100 ng/mL SCF and 10 U/mL IL-10 prior to activation with PGN. PGD2 and LTC4 were assayed in the cell-free supernatant by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (LTC4; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ; PGD2; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Secretory granule exocytosis was determined by measuring the concentration of β-hexosaminidase in the supernatant and lysed cell pellets as described.22 In selected experiments, mast cells were sensitized for 1 hour at 37°C with a 1:300 dilution of monoclonal IgE anti-TNP derived from ascites and stimulated with TNP-BSA or were stimulated with SCF as described.23,24

Arachidonic acid release

Release of radiolabeled arachidonic acid was determined in BMMCs that had been labeled to equilibrium by incubation overnight with [14C] arachidonic acid (0.1 μCi [0.0037 MBq]/mL medium) and then washed prior to activation with Pam3CSK4. The amount of radiolabel released into the medium was expressed as a percent of intracellular [14C] lipids in unstimulated cells.

Western blotting

BMMCs (5 × 106 cells /mL) were activated with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 for 1 to 60 minutes and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 volumes of ice-cold HBSS and centrifugation at 120g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellets were analyzed for expression of specific proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) immunoblotting as described.19 Primary antibodies were used at 1 μg/mL. Bound primary antibodies were detected using goat anti–rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:3000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, West Grove, PA) and enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Membranes used for detection of phosphoproteins were stripped and reprobed with antibodies to the total (phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated) respective protein. The expression of each phosphoprotein was determined by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software.25 Expression was corrected for expression of total protein by dividing the intensity of each phosphoprotein band by the intensity of the respective total protein band.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by ANOVA for kinetic and time-course data. Statistical analysis for a single dose or time was performed using Student t test. Differences were considered statistically significant for P values of less than .05. In determining the “n” for any given experiment, each individual culture of BMMCs was from a separate mouse and each “n” provides the number of separate BMMC cultures of each genotype from which data were derived.

Results

Group V sPLA2 amplifies the cPLA2α-dependent generation of eicosanoids by BMMCs in response to TLR2 stimulation

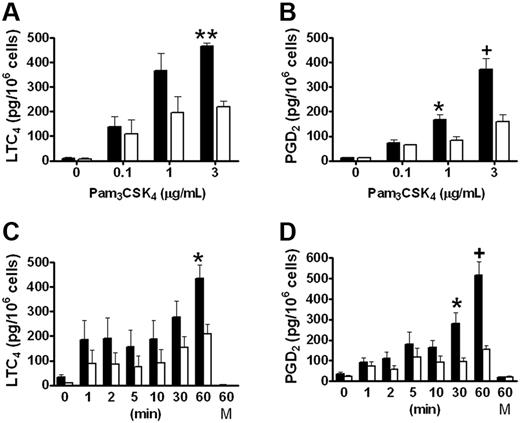

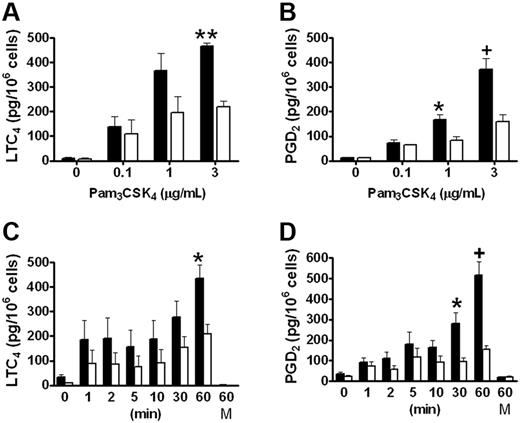

We have previously reported that group V sPLA2 amplifies the cPLA2α-dependent generation of eicosanoids by resident peritoneal macrophages in response to zymosan,18 which signals in part through TLR2.26 To evaluate the role of group V sPLA2 in the immediate phase of eicosanoid generation elicited in response to TLR2 signaling, we measured LTC4 and PGD4 generation from Pla2g5-null and wild-type BMMCs stimulated with the triacylated peptide Pam3CSK4, an agonist of the TLR1/TLR2 heterodimer. LTC4 and PGD2 were released in a dose- and time-dependent manner by both Pla2g5-null and wild-type BMMCs that were maximal 60 minutes after stimulation with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 (Figure 1). Neither eicosanoid was released at 60 minutes in the absence of Pam3CSK4 (Figure 1C-D). The kinetics of eicosanoid generation appeared to be biphasic with a small initial release of LTC4 and PGD2 within the first 5 minutes and a second phase that began between 10 and 30 minutes and that was maximal at 60 minutes. There was no further increase in eicosanoid generation after 60 minutes (data not shown). The release of both eicosanoids was significantly attenuated in Pla2g5-null BMMCs compared with wild-type BMMCs, the attenuation being most marked at 60 minutes (P < .001 and P < .0001 for LTC4 and PGD2, respectively, by ANOVA for both dose-response and kinetic analyses). The maximal quantities of LTC4 and PGD2 generated in response to Pam3CSK4 were 449 ± 28 and 444 ± 43 pg/106 cells, respectively, for wild-type BMMCs and 214 ± 22 and 156 ± 17 pg/106 cells, respectively, for Pla2g5-null BMMCs. The release of eicosanoids in response to PGN, a TLR2/TLR6 agonist, was less robust than in response to Pam3CSK4, and was also attenuated in Pla2g5-null BMMCs (data not shown). Eicosanoid generation from BMMCs in response to PAM3CSK4 was not accompanied by release of the preformed granule-associated mediator, β-hexosaminidase (data not shown).

LTC4 and PGD2 generation in response to Pam3CSK4 is attenuated in Pla2g5–null BMMCs. (A-B) BMMCs from wild-type (shaded bars) and Pla2g5-null (open bars) mice were incubated for 60 minutes with the indicated concentrations of Pam3CSK4. (C-D) BMMCs from wild-type (shaded bars) and Pla2g5-null (open bars) mice were incubated for 0 to 60 minutes with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 or with medium alone (M) as a control. Supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (A,C) and PGD2 (B,D) by EIA. The values are the mean ± SEM of results from 2 independent experiments obtained from 6 separate cultures of both wild-type and Pla2g5-null BMMCs (n = 6). *P < .05, +P < .01, **P < .001, by Student t test in posthoc analyses after ANOVA.

LTC4 and PGD2 generation in response to Pam3CSK4 is attenuated in Pla2g5–null BMMCs. (A-B) BMMCs from wild-type (shaded bars) and Pla2g5-null (open bars) mice were incubated for 60 minutes with the indicated concentrations of Pam3CSK4. (C-D) BMMCs from wild-type (shaded bars) and Pla2g5-null (open bars) mice were incubated for 0 to 60 minutes with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 or with medium alone (M) as a control. Supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (A,C) and PGD2 (B,D) by EIA. The values are the mean ± SEM of results from 2 independent experiments obtained from 6 separate cultures of both wild-type and Pla2g5-null BMMCs (n = 6). *P < .05, +P < .01, **P < .001, by Student t test in posthoc analyses after ANOVA.

To directly determine the role of group V sPLA2 in amplifying the release of arachidonic acid, we labeled BMMCs to equilibrium with [14C]-labeled arachidonic acid and examined its release from Pla2g5-null and wild-type BMMCs in response to Pam3CSK4. Radiolabel was detected in the culture medium 60 minutes after stimulation. Net release was 0.31% ± 0.01% and 0.16% ± 0.03% in wild-type and Pla2g5-null BMMCs, respectively (n = 3; P = .01).

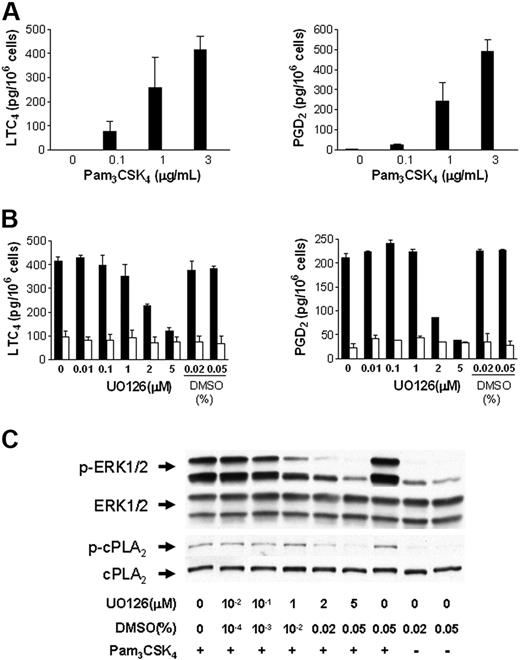

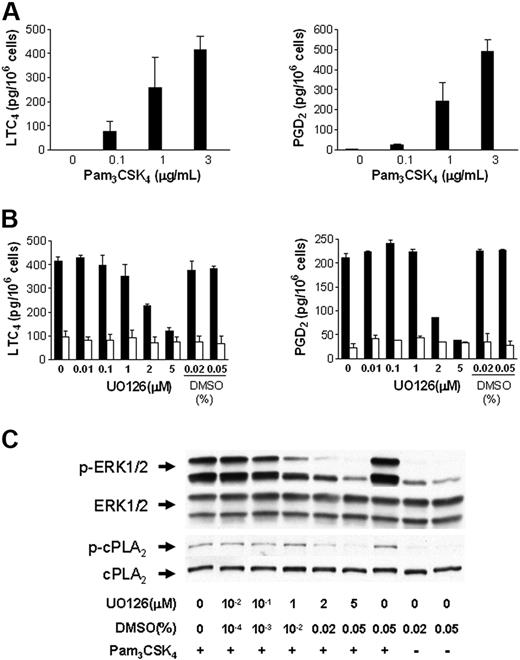

cPLA2α is essential for the immediate phase of TLR2-dependent eicosanoid generation

To determine if cPLA2α is essential for the immediate release of LTC4 and PGD2 by BMMCs in response to TLR2 stimulation, BMMCs from Pla2g4a-null and wild-type control mice were stimulated with 0.1 to 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 for 60 minutes (Figure 2A). LTC4 and PGD2 generation were undetectable in BMMCs from Pla2g4a-null mice compared with 416 ± 55 pg/106 cells of LTC4 and 489 ± 62 pg of PGD2/106 cells, in control BMMCs stimulated with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 (n = 3; P < .001).

TLR2-dependent LTC4 and PGD2 generation in BMMCs requires cPLA2α. (A) BMMCs from wild-type (▬) and Pla2g4a-null (▭) mice were incubated for 60 minutes with the indicated concentrations of Pam3CSK4. Supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left panel) and PGD2 (right panel) by EIA. The values are the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments with 3 separate cultures of each strain of BMMCs (n = 3). (B-C) BALB/c BMMCs were treated with the indicated concentration of UO126 or with DMSO for 15 minutes and stimulated with (■) or without (□) 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 for 30 minutes. The supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left panel) and PGD2 (right panel) by EIA (B); the values are the mean ± SEM (n = 3). The phosphorylation of ERK-1/2 and cPLA2α was assessed by Western blotting (C).

TLR2-dependent LTC4 and PGD2 generation in BMMCs requires cPLA2α. (A) BMMCs from wild-type (▬) and Pla2g4a-null (▭) mice were incubated for 60 minutes with the indicated concentrations of Pam3CSK4. Supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left panel) and PGD2 (right panel) by EIA. The values are the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments with 3 separate cultures of each strain of BMMCs (n = 3). (B-C) BALB/c BMMCs were treated with the indicated concentration of UO126 or with DMSO for 15 minutes and stimulated with (■) or without (□) 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 for 30 minutes. The supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left panel) and PGD2 (right panel) by EIA (B); the values are the mean ± SEM (n = 3). The phosphorylation of ERK-1/2 and cPLA2α was assessed by Western blotting (C).

cPLA2α is activated by phosphorylation at serine 505 by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) extracellular receptor–stimulated kinase (ERK).27 We therefore examined the effect of U0126, an inhibitor of MEK, the MAPK kinase immediately upstream of ERK, on eicosanoid generation and the phosphorylation of ERK and cPLA2α. Wild-type BMMCs were incubated with U0126 for 15 minutes prior to stimulation with 3 μg/mL PAM3CSK4 for 30 minutes. U0126 inhibited LTC4 and PGD2 generation from BALB/c BMMCs in response to PAM3CSK4 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B). Inhibition was apparent at doses greater than 1 μM and was complete with 5 μM U0126. Concentrations of the diluent, DMSO, equivalent to that provided with 2 μM and 5 μM U0126, did not inhibit LTC4 or PGD2 generation. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and cPLA2α was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by U0126 (Figure 2C) confirming the role of ERK1/2 in the activation of cPLA2α and the ensuing eicosanoid generation in response to TLR2 stimulation.

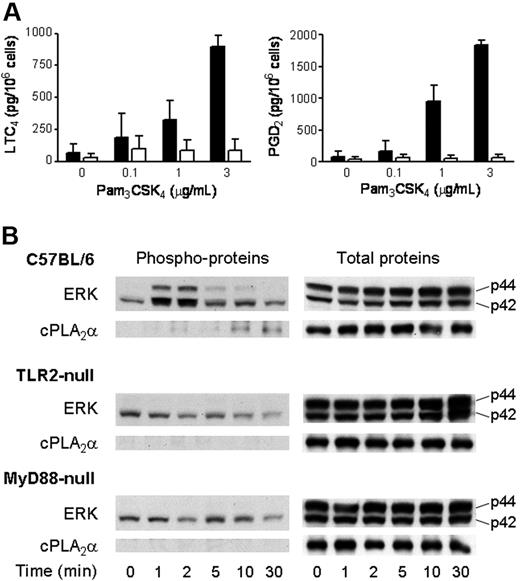

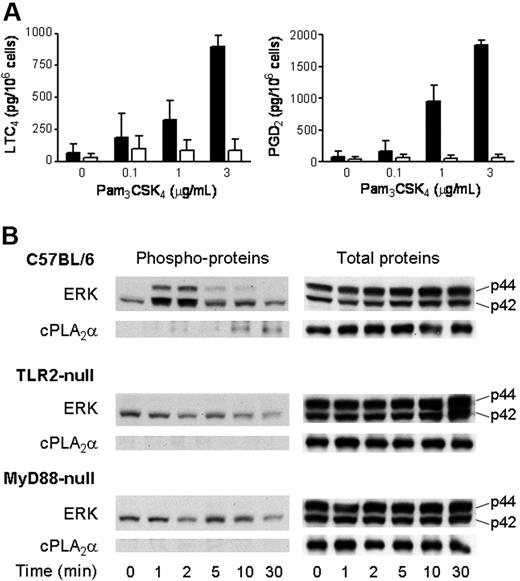

Eicosanoid generation by BMMCs in response to PAM3CSK4 requires TLR2 and MyD88

To ensure that eicosanoid generation in response to Pam3CSK4 was dependent upon TLR2 and was not due to stimulation of an alternate receptor by an impurity in the preparation of the ligand, we examined eicosanoid generation by BMMCs derived from Tlr2-null mice and strain-matched C57BL/6 controls. In 3 separate experiments, LTC4 and PGD2 generation in response to Pam3CSK4 was undetectable above background in Tlr2-null BMMCs (< 25 pg/106 cells), whereas wild-type C57BL/6 BMMCs provided 725 ± 133 pg/106 cells of LTC4 and 1274 ± 586 pg/106 cells of PGD2 (mean ± SEM, n = 4). Eicosanoid generation in response to PGN was also absent in Tlr2-null BMMCs (data not shown).

TLRs signal through an adaptor protein that associates with their intracellular Toll/IL-1R/resistance (TIR) domain. MyD88 is commonly used as the adaptor, and both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways have been described.28 We therefore examined the release of LTC4 and PGD2 in BMMCs derived from Myd88-null mice and strain-matched C57BL/6 controls. LTC4 and PGD2 generation in response to Pam3CSK4 was negligible and not significantly above background in Myd88-null BMMCs compared with that in C57BL/6 BMMCs (P < .002 and P < .001, respectively; n = 3, Figure 3A).

Activation of ERK and cPLA2α and the ensuing LTC4 and PGD2 generation by BMMCs in response to Pam3CSK4 require TLR2 and MyD88. (A) BMMCs derived from Myd88-null (□) and wild-type C57BL/6 (■) mice were incubated for 60 minutes with the indicated concentrations of Pam3CSK4 for 60 minutes. The supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left panel) and PGD2 (right panel) by EIA. (n = 3). Error bars indicate SEM. (B) BMMCs derived from Tlr2-null (n = 3), Myd88-null (n = 3), and wild-type C57BL/6 (n = 4) mice were incubated with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 in a time-dependent manner. Pellets were analyzed for phosphorylated (left panels) or total (right panels) ERK and cPLA2α by Western blotting.

Activation of ERK and cPLA2α and the ensuing LTC4 and PGD2 generation by BMMCs in response to Pam3CSK4 require TLR2 and MyD88. (A) BMMCs derived from Myd88-null (□) and wild-type C57BL/6 (■) mice were incubated for 60 minutes with the indicated concentrations of Pam3CSK4 for 60 minutes. The supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left panel) and PGD2 (right panel) by EIA. (n = 3). Error bars indicate SEM. (B) BMMCs derived from Tlr2-null (n = 3), Myd88-null (n = 3), and wild-type C57BL/6 (n = 4) mice were incubated with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 in a time-dependent manner. Pellets were analyzed for phosphorylated (left panels) or total (right panels) ERK and cPLA2α by Western blotting.

In both Tlr2-null and Myd88-null BMMCs, there was detectable baseline phosphorylation of p42 ERK that did not increase in response to Pam3CSK4, in contrast to the time-dependent and transient increase in p42 ERK phosphorylation that was observed in wild-type C57BL/6 BMMCs (Figure 3B). Likewise, the time-dependent sequential phosphorylation of p44 ERK and cPLA2α that was observed in wild-type C57BL/6 BMMCs in response to Pam3CSK4 was not detectable in either Tlr2-null or Myd88-null BMMCs (Figure 3B). Thus, TLR2 and MyD88 are essential for activation of ERK, phosphorylation of cPLA2α, and eicosanoid generation in response to Pam3CSK4 stimulation of BMMCs.

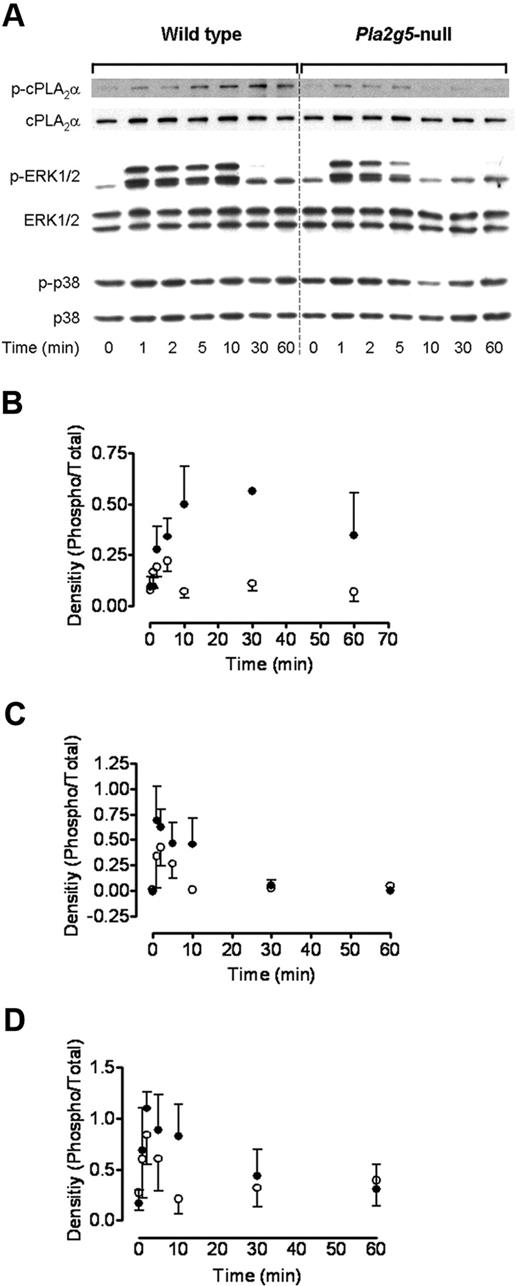

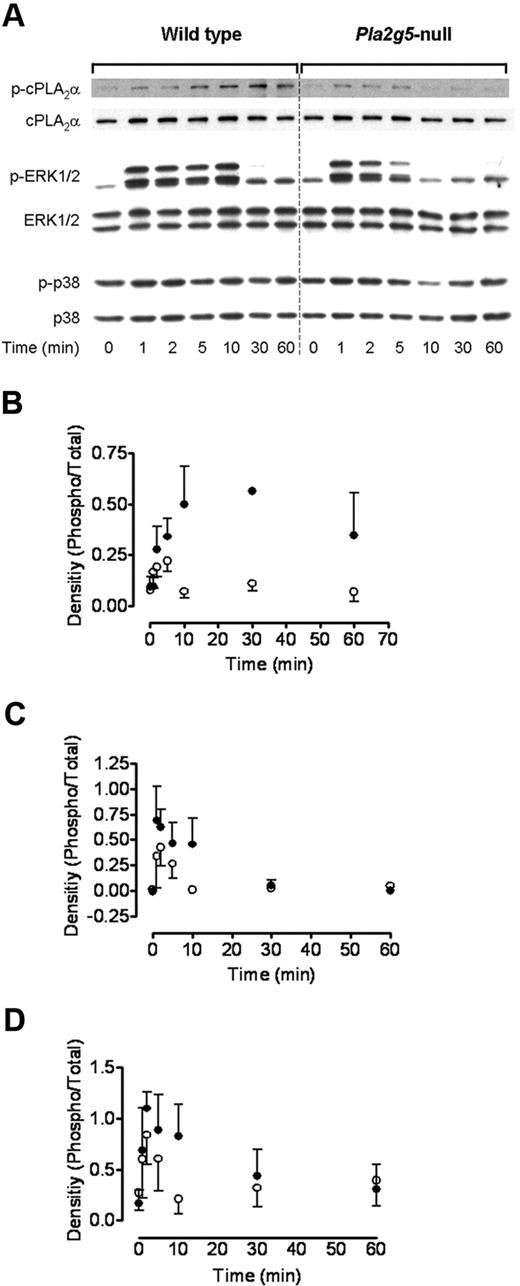

Group V sPLA2 amplifies the action of cPLA2 by regulating ERK phosphorylation

To elucidate the mechanisms through which group V sPLA2 regulates cPLA2α-dependent eicosanoid generation, we examined the effect of deleting Pla2g5 on phosphorylation of cPLA2α and its upstream MAP kinases, ERK and p38. BMMCs from Pla2g5-null and wild-type mice were incubated with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 for up to 60 minutes, and phosphoprotein expression was examined by Western blotting (Figure 4). The phosphorylation of cPLA2α in response to Pam3CSK4 was detectable within 1 to 2 minutes and increased to a maximum at 10 to 30 minutes in wild-type BMMCs; residual phosphorylation was still detectable 60 minutes after stimulation. In contrast, in Pla2g5-null BMMC phosphorylation was also detectable within 1 to 2 minutes, but the further rise in phosphorylation and sustained phosphorylation after 5 minutes were markedly attenuated (n = 3; P = .012; Figure 4A,B).

Group V sPLA2 amplifies ERK-dependent phosphorylation of cPLA2α. BMMCs from wild-type (left panels) and Pla2g5–null (right panels) mice were incubated for 0 to 60 minutes with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4. Expression of phosphorylated (p) and total cPLA2α, ERK-1/2, and p38 was assessed by Western blotting. (A) Representative data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (B-D) Expression of phospho-cPLA2α (B), phospho-p44 ERK (C), and phospho-p42 ERK was quantified using the Image J software and was expressed as a ratio of the intensity of the respective total protein band (n = 3). Error bars indicate SEM.

Group V sPLA2 amplifies ERK-dependent phosphorylation of cPLA2α. BMMCs from wild-type (left panels) and Pla2g5–null (right panels) mice were incubated for 0 to 60 minutes with 3 μg/mL Pam3CSK4. Expression of phosphorylated (p) and total cPLA2α, ERK-1/2, and p38 was assessed by Western blotting. (A) Representative data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (B-D) Expression of phospho-cPLA2α (B), phospho-p44 ERK (C), and phospho-p42 ERK was quantified using the Image J software and was expressed as a ratio of the intensity of the respective total protein band (n = 3). Error bars indicate SEM.

Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 preceded that of cPLA2α and was apparent within 1 minute of PAM3CSK4 stimulation in both wild-type and Pla2g5-null BMMCs (Figure 4A,C-D). This phosphorylation was sustained to 10 minutes in wild-type BMMCs and was barely detectable at 30 minutes. In contrast, ERK1/2 phosphorylation declined rapidly in Pla2g5-null BMMCs and was undetectable by 10 minutes (n = 3; P = .015 compared with wild-type BMMCs). There was no phosphorylation of cPLA2α or ERK1/2 up to 60 minutes in the absence of Pam3CSK4 (data not shown).

Phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase was detectable in the absence of specific stimulation (Figure 4A) and increased modestly and to a similar extent in wild-type and Pla2g5-null BMMCs at 1 and 2 minutes after PAM3CSK4 stimulation.

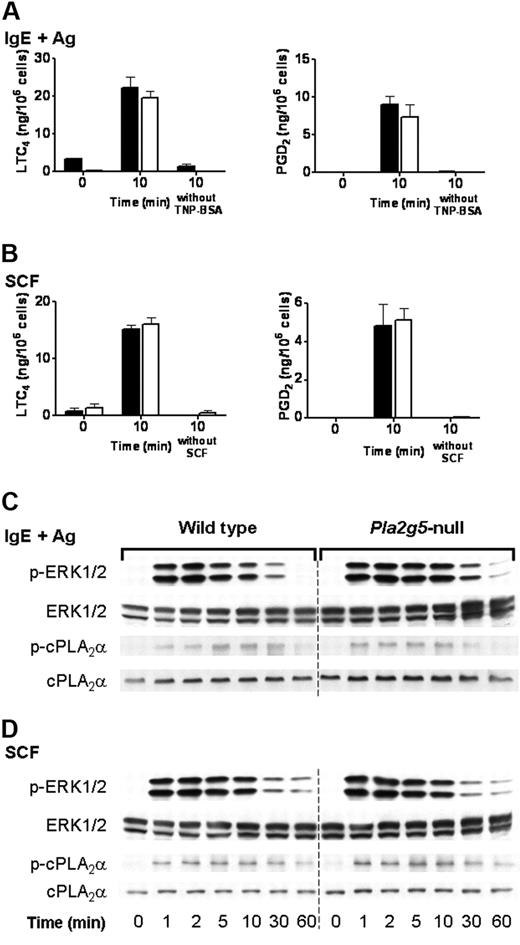

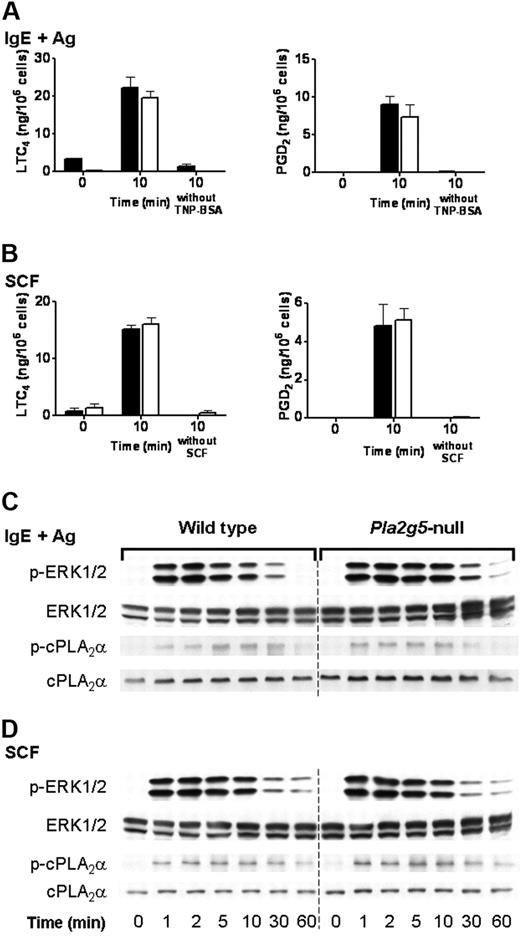

The regulation of ERK and cPLA2α by group V sPLA2 is specific for TLR2 signaling

We have previously reported that the immediate phase of eicosanoid generation by BALB/c BMMCs stimulated through FcεRI or through c-kit is intact in Pla2g5-null BMMCs.23 We therefore examined the phosphorylation of ERK and cPLA2α in Pla2g5-null and wild-type BALB/c BMMCs in response to signaling through FcεRI and c-kit. Pla2g5-null and wild-type BMMCs were stimulated for 10 minutes with SCF or were sensitized with IgE anti-TNP and activated for 10 minutes with TNP-BSA. There was no difference in LTC4 generation, or PGD2 generation, in response to IgE and antigen (Figure 5A) or SCF (Figure 5B) between Pla2g5−/− and wild-type BMMCs, as previously reported. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was apparent within 1 minute of stimulation, reached a maximum at 2 to 5 minutes, and then declined (Figure 5C-D). The phosphorylation of cPLA2α in response to SCF or TNP-BSA was detectable at 1 minute and increased to a maximum at 10 to 30 minutes and then declined to baseline levels by 60 minutes (Figure 5C-D). There was no detectable difference in the kinetics or degree of phosphorylation of cPLA2α or ERK between wild-type and Pla2g5-null BMMCs in response to stimulation with IgE and antigen (Figure 5C) or SCF (Figure 5D).

The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is intact in Pla2g5-null BMMCs stimulated with IgE and antigen or SCF. (A-B) BMMCs from wild-type (shaded bars) and Pla2g5-null (open bars) mice were sensitized with IgE anti-TNP and stimulated with 100 ng/mL TNP-BSA or buffer alone for 10 minutes (A) or were stimulated for 10 minutes with 100 ng/mL SCF or buffer alone (B). Supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left) and PGD2 (right) by EIA. The values are the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments with 3 separate cultures of each strain of BMMCs (n = 3). (C-D) BMMCs from wild-type (left) and Pla2g5-null (right) mice were stimulated with IgE and antigen (C) or with SCF (D) for up to 60 minutes. Pellets were analyzed for phosphorylated (p) and total ERK-1/2 and cPLA2α by Western blotting.

The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is intact in Pla2g5-null BMMCs stimulated with IgE and antigen or SCF. (A-B) BMMCs from wild-type (shaded bars) and Pla2g5-null (open bars) mice were sensitized with IgE anti-TNP and stimulated with 100 ng/mL TNP-BSA or buffer alone for 10 minutes (A) or were stimulated for 10 minutes with 100 ng/mL SCF or buffer alone (B). Supernatants were assayed for LTC4 (left) and PGD2 (right) by EIA. The values are the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments with 3 separate cultures of each strain of BMMCs (n = 3). (C-D) BMMCs from wild-type (left) and Pla2g5-null (right) mice were stimulated with IgE and antigen (C) or with SCF (D) for up to 60 minutes. Pellets were analyzed for phosphorylated (p) and total ERK-1/2 and cPLA2α by Western blotting.

Discussion

TLRs are dimeric receptors that recognize molecular signals on pathogenic organisms (pathogen-associated molecular patterns). TLR2 dimerizes with TLR1 to recognize triacylated bacterial lipopeptides mimicked by PAM3CSK4 or with TLR6 to recognize diacylated peptides such as Mycoplasma macrophage–activating lipopeptide 2 (MALP-2), PGN, and lipoteichoic acid.28,29 In common with the IL-1β and IL-18 receptors, TLRs signal through a cytoplasmic TIR domain that associates with the adaptor protein MyD88, leading to activation of downstream kinases. MyD88-independent signaling can occur through TRIF (TIR domain–containing adaptor-inducing IFNβ) or TRAM (TRIF-related adaptor molecule). These early signaling events couple to the NFκB pathway and to MAP kinases to regulate mediator release and cytokine secretion. While there is a large body of data on the mechanisms of TLR-dependent cytokine generation, there is limited information on how TLRs elicit eicosanoid production. In general, eicosanoid biosynthesis can be divided into 2 phases. In the immediate phase, exemplified by FcεRI-dependent mast cell activation, leukotriene and prostaglandin release begins within minutes of cellular activation and is dependent on constitutively expressed 5-LO and COX-1, respectively.19,30-32 In the delayed phase, prostanoids are generated over several hours, without accompanying leukotriene biosynthesis, in a manner that requires induction of COX-2.19,32 LPS is well established as a potent inducer of COX-2 expression and delayed prostanoid production.33 Use of siRNA and dominant-negative constructs established a role for both TRIF and MyD88 in cPLA2α-dependent release of arachidonic acid in the mouse RAW264.7 macrophage cell line in response to LPS.34 LPS-induced activation of cPLA2α was also suppressed by inhibitors of p38 or ERK.34 While stimulation of human culture-derived mast cells with PGN elicited LTC4 generation,5 the mechanism has not been explored. Our data therefore provide the first insight into the mechanisms by which TLR signaling elicits the rapid generation of eicosanoids and specifically of leukotrienes.

LTC4 and PGD2 generation in response to TLR2 agonists was dependent on cPLA2α, which was activated by ERK (Figure 2). MyD88 was required for the sequential activation of ERK and cPLA2α (Figure 3), suggesting that MyD88-independent pathways are not involved. While the early phases of ERK and cPLA2α phosphorylation were intact in Pla2g5-null BMMCs, their sequential sustained phosphorylation was attenuated (Figure 4). Interestingly, eicosanoid generation by BMMCs in response to TLR2 stimulation was biphasic with a small early phase that peaked within 10 minutes, and a second more substantial phase that was maximal at 60 minutes (Figure 1). The attenuation of PGD2 and LTC4 generation was most marked at 60 minutes. Our data therefore indicate that group V sPLA2 regulates the activation of cPLA2α by sustaining the activation of ERK, which is critical for the sustained activation of cPLA2α in response to TLR2 stimulation. The sustained phosphorylation of cPLA2α appears responsible for the later phase of LTC4 and PGD2 generation, which is therefore attenuated in Pla2g5-null BMMCs.

sPLA2 enzymes have previously been shown to stimulate the sequential activation of MAP kinase and cPLA2α when added exogenously to mouse BMMCs35 or the 1321N1 astocytoma cell line.36 Transfection of mouse mesangial cells with group V sPLA2 or group IIA sPLA2 enhanced H2O2-stimulated MAP kinase activation and cPLA2α-dependent eicosanoid generation in an ERK-dependent manner.37 We provide the first demonstration for a role for endogenous group V sPLA2 in regulating the sequential activation of ERK and cPLA2α. It should be noted that we used BMMCs derived from Pla2g5-null BALB/c mice. Because the allele carrying the disruption of Pla2g5 is derived from 129 ES cells, which carry a disruption of the neighboring Pla2g2a, these mice lack both group V sPLA2 and group IIA sPLA2.17,18 That group IIA PLA2 is not required for the sustained phosphorylation of ERK and cPLA2 is apparent from experiments with BMMCs derived from C57BL/6 BMMCs that also lack group IIA sPLA238 and that were used as controls for mice deficient in TLR2, MyD88, or cPLA2α (Figure 3). Ongoing studies are addressing the mechanisms through which group V sPLA2 sustains the activation of ERK.

While exogenous sPLA2 or sPLA2 overexpressed by transfection in various cells is capable of amplifying the essential role of cPLA2α in the biosynthesis of eicosanoids,39-43 the role of the endogenous sPLA2 enzymes has remained poorly defined. Using mice in which the gene encoding group V sPLA2 was deleted, we demonstrated that this sPLA2 amplifies the essential function of cPLA2α in zymosan-induced LTC4 and PGE2 biosynthesis by resident mouse peritoneal macrophages.18 This translated in vivo to attenuation of the early phase of zymosan-induced peritonitis.18 We then demonstrated that group V sPLA2 regulates phagocytosis of zymosan by resident peritoneal macrophages.17 Others have demonstrated that group V sPLA2 has bactericidal activity toward M luteus that is enhanced after treatment of the bacteria with lysozyme.44,45 These combined data suggest a role for group V sPLA2 in innate immune responses. Our present findings strengthen the suggestion that this sPLA2 plays a role in innate immunity, a role that is shared with group IIA sPLA2, which is a more potent bactericidal agent than group V sPLA2 with a spectrum of activity that extends to Gram-negative bacteria.44,45 Furthermore, transgenic mice expressing human group IIA sPLA2 are resistant to infection with Bacillus anthracis, and in vivo administration of recombinant group IIA sPLA2 protected mice against infection with this organism.46 Thus, a picture is emerging that sPLA2 enzymes may have evolved and retained their diversity in mammals due their role in innate immunity.

The role of group V sPLA2 in regulating eicosanoid generation, inflammation, and phagocytosis contrasts with the role of cPLA2α revealed through gene disruption. Lack of cPLA2α leads to profound deficits in the generation of leukotrienes and prostaglandins and results in the marked attenuation of inflammatory responses and also certain physiologic functions such as parturition,13-16 raising important questions as to the possible side effects of targeting cPLA2α in human disease. In contrast, disruption of group V sPLA2 led to modest deficits in eicosanoid generation and phagocytosis.17,18,23 Thus, sPLA2 enzymes, and group V sPLA2 in particular, might be attractive therapeutic targets in inflammation, blunting rather than ablating the generation of lipid mediators. We have found that group V sPLA2 regulates eicosanoid generation from mouse BMMCs in response to stimulation through TLR2 (Figure 1) with a limited role in regulating eicosanoid generation in response to signaling through FcεRI or c-kit that is limited to a strain-dependent role in delayed phase COX-2 induction and PGD2 generation (Figure 5).23 If this specificity extends to human cells, inhibition of group V sPLA2 might prove a useful strategy in targeting overexuberant TLR-dependent inflammation while leaving allergic inflammatory responses substantially intact. Whether targeting sPLA2 in humans would be accompanied by an increase in susceptibility to infection remains to be seen and will be addressed in the first instance in Pla2g5-null mice. However, it is notable that while mice lacking 5-LO display impaired phagocytosis and killing of Klebsiella pneumoniae,47 an increased risk of opportunist infections from the use in humans of the 5-LO inhibitor zileuton has not emerged to date.

In conclusion, our data provide the first dissection of rapid eicosanoid generation in response to TLR stimulation, demonstrate a role for endogenous group V sPLA2 in regulating the sequential activation of ERK and cPLA2α, and provide further evidence that group V sPLA2 is a participant in innate immune responses.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants HL 070946, HL36110, DK39773, and DK38452 from the National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: E.K. designed and performed the research, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the paper; J.V.B. contributed Pla2g4a-null mice; and J.P.A. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jonathan P. Arm, Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy, Brigham and Women's Hospital, 1 Jimmy Fund Way, Room 638B, Boston MA 02115; e-mail: jarm@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.