In this issue of Blood, Haselmayer and colleagues demonstrate that platelets express the ligand for the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM-1), and show that its interaction with neutrophil TREM-1 amplifies neutrophil activation.

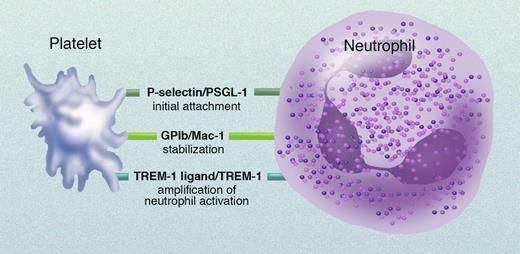

Patelets adhere to neutrophils and monocytes via a number of receptor/counterreceptor pairs (see figure).1 Activated platelets degranulate, thereby expressing platelet surface P-selectin. The initial adhesion of platelets to neutrophils and monocytes occurs via platelet surface P-selectin binding to its constitutively expressed leukocyte counterreceptor, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1). Stabilization of leukocyte-platelet aggregates occurs via the binding of leukocyte surface Mac-1 (also known as integrin αMβ2 and CD11b/CD18) to platelet surface glycoprotein Ib (GPIb). In addition, leukocyte surface Mac-1 binds to the platelet surface integrin αIIbβ3 (with fibrinogen as a bridging molecule) and/or to platelet surface junctional adhesion molecule 3 (JAM-3).

Receptor/counterreceptor pairs involved in platelet-neutrophil interactions. Professional illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Receptor/counterreceptor pairs involved in platelet-neutrophil interactions. Professional illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Haselmayer and colleagues have now identified an additional receptor/counterreceptor pair involved in this process: neutrophil surface TREM-1 and platelet surface TREM-1 ligand. The interaction between TREM-1 and TREM-1 ligand is not required for neutrophil-platelet aggregate formation, but results in enhancement of neutrophil activation—as determined by respiratory burst activity and release of interleukin 8. TREM-1 is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and plays an important role in the innate immune response related to sepsis.2 However, the identity and location of the natural TREM-1 ligands were unknown. Haselmayer and colleagues have now discovered that TREM-1 ligand is expressed on human platelets. The platelet surface expression of TREM-1 ligand is not up-regulated by platelet activation, and the binding of TREM-1 to TREM-1 ligand on platelets does not result in platelet activation.

These findings open up a number of new avenues for further investigation. First, the molecular identity of the TREM-1 ligand on platelets remains to be determined. Second, although Haselmayer and colleagues focus on neutrophil activation, TREM-1 is also expressed on monocytes.2 Therefore, the functional consequences of monocyte surface TREM-1 binding to platelet surface TREM-1 ligand should also be investigated. Third, given the role of the TREM-1/TREM-1 ligand interaction in sepsis,2 Haselmayer and colleagues raise the possibility of targeted therapy of this receptor/counterreceptor pair in the treatment of sepsis.

Fourth, although not mentioned by Haselmayer et al, the study of the TREM-1/TREM-1 ligand interaction may also be fruitful in other inflammatory diseases in which monocyte-platelet and neutrophil-platelet aggregates play an important role. For example, circulating leukocyte-platelet aggregates, especially monocyte-platelet aggregates, promote the formation of atherosclerotic lesions,3 are increased in acute coronary syndromes, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease,4 and are an early marker of acute myocardial infarction.5 Increased circulating monocyte-platelet and neutrophil-platelet aggregates have also been reported in numerous other conditions, including diabetes mellitus, cystic fibrosis, asthma, pre-eclampsia, placental insufficiency, migraine, nephrotic syndrome, hemodialysis, sickle cell disease, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, septic multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, antiphospholipid syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, myeloproliferative disorders, Kawasaki disease, and Alzheimer disease.4 Future studies on TREM-1/TREM-1 ligand interactions will no doubt add to platelet and leukocyte aggregate knowledge.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■