Abstract

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) frequently carries the t(2;5)(p23;q35), resulting in aberrant expression of nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NPM-ALK). We show that in 293T and Jurkat cells, forced expression of active NPM-ALK, but not kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK (210K>R), induced JNK and cJun phosphorylation, and this was linked to a dramatic increase in AP-1 transcriptional activity. Conversely, inhibition of ALK activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells resulted in a concentration-dependent dephosphorylation of JNK and cJun and decreased AP-1 DNA-binding. In addition, JNK physically binds NPM-ALK and is highly activated in cultured and primary NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. cJun phosphorylation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells is mediated by JNKs, as shown by selective knocking down of JNK1 and JNK2 genes using siRNA. Inhibition of JNK activity using SP600125 decreased cJun phosphorylation and AP-1 transcriptional activity and this was associated with decreased cell proliferation and G2/M cell-cycle arrest in a dose-dependent manner. Silencing of the cJun gene by siRNA led to a decreased S-phase cell-cycle fraction associated with upregulation of p21 and downregulation of cyclin D3 and cyclin A. Taken together, these findings reveal a novel function of NPM-ALK, phosphorylation and activation of JNK and cJun, which may contribute to uncontrolled cell-cycle progression and oncogenesis.

Introduction

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL),1 a distinct type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T/null cell lineage, is frequently associated with the t(2;5)(p23;q35), resulting in aberrant expression of the nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NPM-ALK) oncogenic kinase.2 The oncogenic potential of NPM-ALK has been shown in vitro and in mouse models. NPM-ALK can transform rodent fibroblasts and bone marrow cells3,4 and induces lymphoid malignancy in mice transplanted with bone marrow cells expressing NPM-ALK retroviral vectors.5 Furthermore, T-cell lymphomas and plasma cell neoplasms develop in NPM-ALK transgenic mice.6 Although the mechanisms of NPM-ALK–mediated oncogenesis are not completely understood, previous studies have shown that NPM-ALK activates known oncogenic pathways, including Shc, IRS-1, phospholipase C-γ, the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT and its downstream effectors FOXO3a and mTOR, and MEK (MAPK [mitogen-activated protein kinase]/ERK kinase)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK).3,4,7-15

The activator protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factor is a dimeric complex that contains members of the Jun (cJun, JunD, and JunB), Fos (c-Fos, FosB, Fra1, Fra2), Maf, and ATF families.16 AP-1 transcription factors belong to the basic leucine-zipper group of DNA binding proteins and form homodimers or heterodimers that bind to DNA recognition elements, known as 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-responsive elements, and cAMP-responsive elements, thus inducing the transcription of numerous target genes. AP-1 regulates a wide range of cellular processes including cell proliferation, death, survival, and differentiation.17 cJun,18 the best characterized member of the AP-1 family, positively regulates cell proliferation.19

The growth-promoting activity of cJun is mediated through transcriptional activation of cell-cycle regulators such as cyclins (cyclin D1, cyclin D3, cyclin A, and cyclin E), as well as suppression of p53 and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21Cip1 (p21), p19ARF, and p16Ink4.20-22

cJun is positively regulated at the transcription level by its own gene product through a positive feedback loop.23 It is well established that phosphorylation of cJun is essential for stimulation of its transcriptional activity.16,24,25 Members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family have been implicated in cJun phosphorylation and regulation. JNKs (cJun N-terminal kinase), so far, are the only protein kinases that phosphorylate the N-terminal sites of cJun at Ser63 and Ser73 residues. ERKs regulate cJun activity through phosphorylation of one of the inhibitory sites located in the C-terminal DNA binding site.26 Phosphorylation of N-terminal sites by JNKs stimulates cJun transcriptional ability by facilitating recruitment of CREB (cyclic adenosine monophosphate–response element binding protein)–binding protein (CBP) coactivator.27

The role of AP-1 transcription factors in lymphomagenesis is currently undergoing investigation. Previous studies have shown that 2 members of the Jun family, cJun and JunB, are expressed at a high level in CD30-positive lymphomas including ALK+ ALCL.28-30 However, the potential role of cJun in ALCL oncogenesis and the molecular mechanisms regulating its activity are unknown.

This study uncovers a novel function of NPM-ALK oncogenic kinase that may contribute to uncontrolled cell-cycle progression and oncogenesis in ALCL. We show that NPM-ALK is capable of phosphorylating and activating JNK, which in turn phosphorylates and activates cJun. This JNK/cJun axis substantially enhances cJun transcriptional activity and appears to confer strong growth-promoting and cell-cycle regulatory signals in ALCL cells through downregulation of a known transcriptional target of cJun, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. These data suggest that modulation of JNK and cJun activity represents a novel target for therapy in patients with NPM-ALK+ ALCL.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

Four cell lines including 2 NPM-ALK+ ALCL, Karpas 299 (a gift of Dr M. Kadin, Beth Israel-Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA), SU-DHL1 (purchased from DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany); a T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Jurkat; and a human embryonic kidney (HEK), 293T (purchased from ATCC, Rockville, MD) were used. Karpas 299, SU-DHL1, and Jurkat cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). HEK 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. All cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1 (each 0.5 × 106 cells/mL) cells were treated with inhibitors of JNK (SP60025; Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA), ERK1/2 (U0126; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY), and ALK (WHI-P154; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA)31,32 activity using the indicated concentrations and time points. Cell viability was assessed using trypan blue exclusion assay in triplicate; the mean percentage of viable cells was calculated.

Plasmids and transfections

The NPM-ALK gene was obtained from Dr S. Morris (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). After amplification with polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the gene was inserted into the pcDNA3.1/V5/HIS/TOPO-TA vector (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and into the pENTR/DTOPO vector. A control pcDNA3.1/V5/HIS/TOPO-TA vector containing the β-galactosidase (lacZ) gene was included in the TOPI clone kit. A mutant polymerase chain reaction (PCR) fragment (K210R) was obtained by amplification using a forward primer that spans a unique BspE1 site (ALK-K210R_F1, 5′-GTGTCCGGAATGCCCAACGACCCAAGCCCCCTGCAAGTGGCTGTGAGGACGCTGCCTG-3′) and includes the 629A>G mutation and a reverse primer that spans a unique Sac1 site (ALK-K210R_R1, 5′-CGCCATGAGCTCCAGCAGGATGAACC-3′). The fragment was amplified using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase with 2.5 mM MgCl2, digested with BspE1 and Sac1 and cloned into a similarly digested NPM-ALK construct replacing the wild-type sequence with mutant. The wild-type and mutant constructs were transformed into One Shot TOP10 cell, single colonies were isolated, DNA was purified, and the sequence was verified. Expression clones were generated using the LR Clonase recombination reaction between the entry vector and the pcDNA-DEST40 Gateaway vector (Invitrogen). Plasmid extraction was performed using the EndoFree Plasmid Maxi kit (Qiagen, Valencia. CA).

HEK 293T cells were stably transfected with empty vector (pDest40), functional NPM-ALK, or kinase-dead mutant NPM/ALK (210K>R) constructs using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Jurkat cells were grown to mid-log phase and were transiently transfected (2 × 106 cells) with 50 μg of the empty vector, active NPM-ALK, or mutant NPM-ALK plasmids using Nucleofector reagents (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were collected at 48 hours and whole lysates were analyzed by Western blotting.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared using the NE-PERTM kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The double-stranded oligonucleotides used included 5′CGCTTGATGACTCAGCCGGAA-3′, which contains a consensus (italicized) or mutant AP-1 binding site (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and were radioactively end-labeled with γ-phosphorus 32 (32P)–ATP (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). For the binding reaction performed at 37°C for 30 minutes, 4 μL of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide (400 000 cpm) and 10 μg nuclear extract were incubated in a total volume of 20 μL containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 0.4 mM EDTA, 0.4 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, and 2 μg poly (dI-dC). After addition of 4 μL of 6× DNA loading buffer the samples were resolved in 6% acrylamide gels, pre-run for 1 hour at 100 volts, in 0.5×TBE at 100 volts. For gel shift assays, 1 μg of 10× concentrated anti-cJun antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the reaction mixture before the addition of the 32P-labeled oligonucleotide and incubated overnight at 4°C.

Kinase assays

Cells were treated with SP60025 at the indicated concentrations. After 48 hours, cell lysates (200 μg of protein) were incubated with immobilized GST-cJun (1-79 amino acids), which precipitates and also serves as a substrate for JNK. After incubation at 4°C overnight, agarose beads were resuspended in kinase reaction buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM MgCl2) in the presence of 200 μM ATP for 30 minutes at 30°C with gentle mixing every 10 minutes. cJun phosphorylation was then detected by Western blotting using a phospho-cJun antibody. Gel loading was normalized by immunoblotting with anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase assay was performed in triplicate using Promega's Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Jurkat cells were transfected with 50μg of empty vector, or NPM-ALK or mutant NPM-ALK (210K>R) plasmids, along with 5 μg of the AP-1 promoter reporter construct containing 3 AP-1 binding sites upstream of the luciferase gene. At 48 hours after transfection, a luciferase assay was performed. Similarly, a luciferase reporter assay was performed in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells first transfected with 5 μg of the AP-1 promoter reporter construct and then treated (at 24 hours) with 20 μM of SP600125. For a normalizing control, 5 ng of plasmid encoding the Renilla luciferase gene was cotransfected into each well in these experiments.

Proliferation assay

Proliferation of viable cells was assessed by incubating 100 μL from each sample with 20 μL of tetrazolium compound [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium; MTS] in a 96-well plate. Absorbance at 49 nm, which is proportional to the number of viable cells, was measured using the CellTiter 96 AQueous cell proliferation assay (Promega) and μQuant spectrophotometer (BIO-TEK Instruments, Winooski, VT). Multiple readings were obtained to ensure that the colorimetric reaction had reached its end point. All treatments were performed in triplicate.

Apoptosis and cell-cycle analysis

Apoptosis was analyzed using annexinV binding and propidium iodide uptake assay (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and flow cytometry as described previously.14 To analyze the cell cycle, 0.5 × 106 cells were treated at the indicated concentrations of SP600125 or siRNA for 48 hours. Cell-cycle analysis was performed using propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. The S-phase fraction of the cell cycle was assessed by a colorimetric BrdU incorporation assay as described elsewhere.14 All experiments were performed at least twice.

Reverse-transcriptase PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Protect Mini Kit (Qiagen). To obtain complementary DNA (cDNA) for reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR), 5μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed at 42°C for 50 minutes in the presence of 0.5 μg of Oligo (Td) 12-18 primer, 10 mM dNTP mix, 1× RT buffer, and 50 units of SuperScript II RT, all provided in the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). For RT-PCR amplification of the JNK1 or JNK2 gene product, the following primers were used: JNK1: 5′-CAGAAGCAAGCGTGACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGGCCAGACCGAAGTCA-3′ (reverse); JNK2: 5′-ATATTGCAGGACGCTGCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTCAGGGTGCAGTCTGA-3′ (reverse). The PCR program included initial DNA denaturation at 95°C (4 minutes), followed by 35 cycles of 95°C (30 seconds), 56°C (30 seconds), and 72°C (1 minute), and, lastly, extension at 72°C (5 minutes). The presence of PCR products was tested using 1.5% agarose gels, ultraviolet light, and the Alpha-Imager system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using standard techniques as described.14 The following antibodies were used: cJun, Ser63p-cJun, Ser73p-cJun, JNK, p-JNK, JNK2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); p21 (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), JNK1, cyclin A, under-phosphorylated Rb (BD Pharmigen), and cyclin D3 (Novocastra, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom). β-actin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) served as a control for protein load and integrity in all immunoblots.

Coimmunoprecipitation studies

Cell lysates from Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1 cell lines were immunoprecipitated with anti-JNK1 (BD Bioscience), anti-JNK1/2, anti-JNK2 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-ALK (Zymed, San Francisco, CA), or isotope IgG1 control (DakoCytomation) antibodies. Briefly, antibodies were cross-linked to Dynabeads-Protein G (Invitrogen) and incubated with 600 μg protein overnight at 4°C according to manufacturer's protocol. Immunocomplexes were then washed with immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (10 mM, Tris-HCL pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaF, 0.5% NP40, 0.5% glucopyranoside, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, and 0.5 mM PMSF) and proteins were eluted by boiling at 95°C for 5 minutes in 1× loading buffer, and then analyzed by Western blotting as described elsewhere.12 The coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed twice.

Knock-down of cJun and JNK by siRNA

The sequences of cJun, JNK1, and JNK2 small interfering (si)RNAs and a negative control siRNA were purchased from Ambion Inc (Austin, TX) and were as follows: cJun: 5′-GGAAGCUGGAGAGAAUCGCtt-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGAUUCUCUCCAGCUUCCtt-3′ (antisense); JNK1: 5′-GGACUUACGUUGAAAACAGtt-3′ (sense) and 5′-CUGUUUUCAACGUAAGUCCtt-3′ (antisense); JNK2: 5′-GCUCUGCGUCACCCAUACAtt-3′ (sense) and 5′-UGUAUGGGUGACGCAGAGCtt-3′(antisense). Transient transfection of Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1 cells was performed using the Nucleofector reagents (Amaxa Biosystems). Approximately 2 × 106 cells were transfected with 0, 20, and 40 μg siRNA using 100 μL Kit T-solution (Amaxa Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 48 hours cJun, JNK1, and JNK2 protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting to confirm adequate silencing of the genes.

Tissue microarray and immunohistochemical methods

ALK+ ALCL tumor specimens from 22 previously untreated patients with ALK+ ALCL were analyzed. All tumors were diagnosed at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center according to the WHO classification.1 Construction of the tissue microarray containing triplicate cores from each tumor and the immunohistochemical methods have been described elsewhere.29,33 The antibodies used were specific for cJun (Cell Signaling Technology; dilution 1:100), Ser63p-cJun, Ser73p-cJun, and p-JNK (Cell Signaling Technology; dilution 1:50). Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in antigen retrieval solution (DakoCytomation) using a household steamer for 40 minutes. Only nuclear staining of tumor cells for p-JNK, Ser73p-cJun, or cJun was considered positive, irrespective of intensity. The percentage of c-Jun or Ser73p-cJun–positive tumor cells was determined by counting at least 500 neoplastic cells in each tumor. In addition, double immunostaining for p-JNK and CD30 was performed using the peroxidase/alkaline phosphatase-based EnVision Doublestain system (DakoCytomation) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Images were obtained with a BX51 Olympus microscope, a DP12 Olympus digital camera, and a universal semi-apochromat UPlan FL lens (40×/0.75 NA) (Olympus, Melville, NY).

Statistical analysis

The association between the percentage of cJun or Ser73p-cJun–positive tumor cells (continuous variables) and JNK activation (categorical variable) was analyzed using the nonparametrical Mann-Whitney test. P value of more than .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were carried out using the Statview program (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).

Results

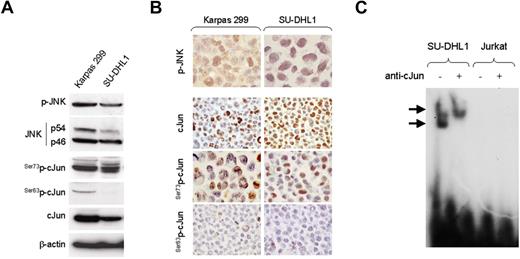

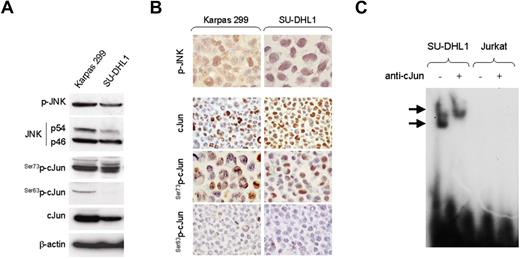

JNK and cJun are highly activated in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cell lines and tumors

We first examined the activation status of JNK in cultured and primary NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. As shown in Figure 1A, JNK isoforms were expressed in both NPM-ALK+ ALCL cell lines tested. These results were confirmed by immunohistochemistry performed in Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1 cell blocks (Figure 1B). Next, we assessed for expression and activation of cJun, a substrate of JNK, in these cell lines. High levels of total cJun were found by Western blot analysis in Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1, confirming previously published data.28 We further assessed for cJun phosphorylation in these cell lines using antibodies specific for Ser73p-cJun and Ser63p-cJun. cJun was highly phosphorylated at serine-73 residue in both NPM-ALK+ ALCL cell lines tested (Figure 1A). Immunohistochemistry performed in cell blocks confirmed that total cJun was expressed in the nucleus at high levels and was predominantly phosphorylated at serine 73 residue in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells (Figure 1B). In addition, the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) revealed a super shift of protein-DNA complex in SU-DHL1 cells preincubated with an antibody specific for cJun, indicating that cJun is present in the AP-1 complexes in NPM-ALK+ ALCL (Figure 1C).

Expression of activated JNK and cJun proteins and AP-1 DNA binding activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) Two NPM-ALK+ ALCL cell lines, Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1, were examined by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for JNK, p-JNK, cJun, and its phosphorylated forms, Ser73p-cJun and Ser63p-cJun. JNK1 and JNK2 are expressed as isoforms of 46 kD and 54 kD, respectively, generated by alternate splicing. Both cell lines were found to express high levels of JNK and cJun, as well as their phosphorylated forms, with Ser73p-cJun being more prominent. Two Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines, L-428 and L-1236, served as positive controls and REH cells, derived from a patient with pre-B-ALL, served as a negative control, respectively, for expression of cJun and p-cJun (data not shown). (B) Immunochistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1 cell blocks using the same antibodies for detection of cJun and their phosphorylated/activated forms. Both NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells revealed nuclear staining for cJun, Ser73p-cJun, and Ser63p-cJun. (C) AP-1 DNA binding activity was assessed in SU-DHL1 and Jurkat by EMSA using the double-stranded consensus oligonucleotides with AP-1–specific binding. Super shift of protein–DNA complex (arrow) was detected in SU-DHL1 cells when nuclear extracts were preincubated with (+) antibody against cJun, indicating the AP-1 complex in ALK+ ALCL cells contains cJun. AP-1 DNA binding activity was undetectable in Jurkat cells that served as a negative control in this experiment. Free DNA is shown in the bottom of the gel.

Expression of activated JNK and cJun proteins and AP-1 DNA binding activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) Two NPM-ALK+ ALCL cell lines, Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1, were examined by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for JNK, p-JNK, cJun, and its phosphorylated forms, Ser73p-cJun and Ser63p-cJun. JNK1 and JNK2 are expressed as isoforms of 46 kD and 54 kD, respectively, generated by alternate splicing. Both cell lines were found to express high levels of JNK and cJun, as well as their phosphorylated forms, with Ser73p-cJun being more prominent. Two Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines, L-428 and L-1236, served as positive controls and REH cells, derived from a patient with pre-B-ALL, served as a negative control, respectively, for expression of cJun and p-cJun (data not shown). (B) Immunochistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1 cell blocks using the same antibodies for detection of cJun and their phosphorylated/activated forms. Both NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells revealed nuclear staining for cJun, Ser73p-cJun, and Ser63p-cJun. (C) AP-1 DNA binding activity was assessed in SU-DHL1 and Jurkat by EMSA using the double-stranded consensus oligonucleotides with AP-1–specific binding. Super shift of protein–DNA complex (arrow) was detected in SU-DHL1 cells when nuclear extracts were preincubated with (+) antibody against cJun, indicating the AP-1 complex in ALK+ ALCL cells contains cJun. AP-1 DNA binding activity was undetectable in Jurkat cells that served as a negative control in this experiment. Free DNA is shown in the bottom of the gel.

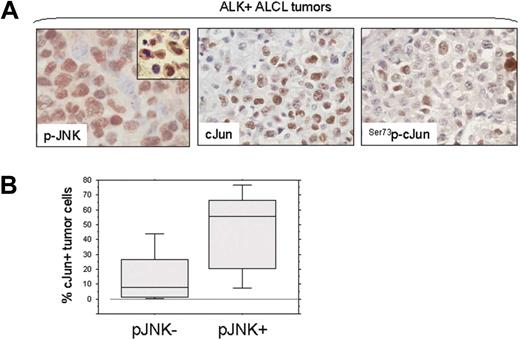

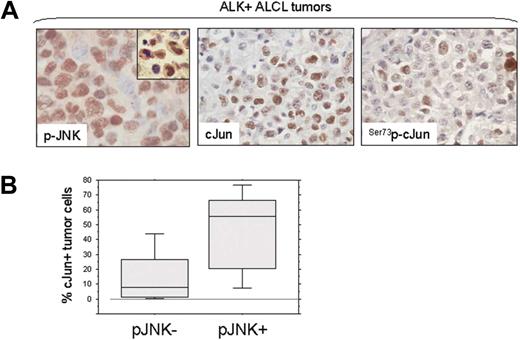

We also assessed the activation status of JNK and cJun (Ser73p-cJun) in ALK+ ALCL tumors by immunohistochemistry using tissue microarrays. Using a 10% cutoff for positivity, p-JNK was expressed in 15 (68%) of 22 ALCL tumors (Figure 2A). Ser73p-cJun expression was found in all ALK+ ALCL tumors with 30% to 100% of tumor cells being positive. In contrast, Ser63p-cJun was detected generally in a small percentage of tumor cells (< 5%). Of note, JNK activation significantly correlated with cJun expression in ALK+ ALCL tumors. The median percentage of cJun+ tumor cells was 56% in the group of p-JNK+ tumors compared with 8% in the group of p-JNK− tumors (P = .018, Mann-Whitney test; Figure 2B).

JNK and cJun activation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL tumors. (A) JNK and cJun phosphorylation were assessed in 22 ALK+ ALCL tumors using immunohistochemistry and a tissue microarray. Using a 10% cutoff, nuclear expression of p-JNK was found in 15 (68%) ALK+ ALCL, with most tumor cells being positive in the p-JNK+ group of tumors. cJun was expressed and was phosphorylated at serine 73 in a variable proportion of tumor cells, in accordance with our recently published data.30 Double immunostaining confirmed the coexpression of CD30 and p-JNK in tumor cells (inset: red, membranous CD30 expression; dark brown, nuclear p-JNK expression). (B) The median percentage of cJun+ tumor cells in ALK+ ALCL was significantly higher in tumors expressing p-JNK than in tumors negative for p-JNK (box and whisker plot). The boxes indicate percentages of cJun+ tumor cells between 25%-75%. The bars indicate percentages of cJun+ tumor cells between 5%-95%.

JNK and cJun activation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL tumors. (A) JNK and cJun phosphorylation were assessed in 22 ALK+ ALCL tumors using immunohistochemistry and a tissue microarray. Using a 10% cutoff, nuclear expression of p-JNK was found in 15 (68%) ALK+ ALCL, with most tumor cells being positive in the p-JNK+ group of tumors. cJun was expressed and was phosphorylated at serine 73 in a variable proportion of tumor cells, in accordance with our recently published data.30 Double immunostaining confirmed the coexpression of CD30 and p-JNK in tumor cells (inset: red, membranous CD30 expression; dark brown, nuclear p-JNK expression). (B) The median percentage of cJun+ tumor cells in ALK+ ALCL was significantly higher in tumors expressing p-JNK than in tumors negative for p-JNK (box and whisker plot). The boxes indicate percentages of cJun+ tumor cells between 25%-75%. The bars indicate percentages of cJun+ tumor cells between 5%-95%.

Taken together, these results suggest that JNK and cJun are highly activated in ALCL cell lines and primary tumor cells.

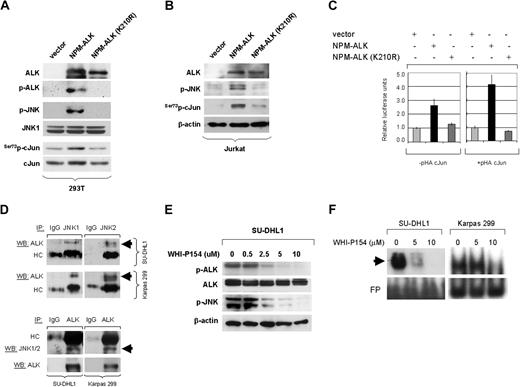

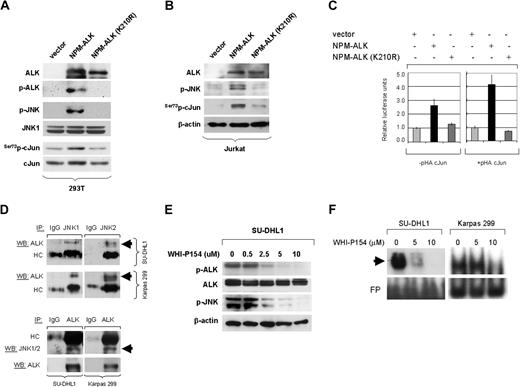

NPM-ALK induces JNK and cJun activation

To test our hypothesis that NPM-ALK is capable of activating JNK, HEK 293T cells were stably transfected with empty vector(pDest40), active NPM-ALK, and a mutant (kinase-dead) NPM-ALK (210K>R) construct. Immunoblots showed that stable expression of functional NPM-ALK in HEK 293T cells resulted in phosphorylation of JNK, followed by activation of cJun at serine 73. Expression of kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK (K210R) was unable to induce activation of JNK or cJun in this in vitro system (Figure 3A). To further confirm these data, a human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line, Jurkat, was transiently transfected with the same NPM-ALK expression plasmids and empty vector. Western blot analysis demonstrated that transient expression of fully functional NPM-ALK in Jurkat cells resulted in a substantial increase in p-JNK levels, which was associated with increased serine 73-phosphorylation of cJun. Again, expression of a kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK (210K>R) could not induce phosphorylation/activation of JNK and cJun in this system (Figure 3B). We also found that kinase activity of NPM-ALK is not affected by JNK activity, because phosphorylation of ALK indicating activation does not change after silencing JNK1 or JNK2 genes (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

NPM-ALK activates JNK and cJun and Induces AP-1 transcriptional activity. (A) HEK 293T cells were stably transfected with expression plasmids including empty vector (pDest40), active NPM-ALK, or mutant NPM-ALK (K210R) with a kinase-dead domain. Expression of NPM-ALK, in cells transfected with functional or kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK, was confirmed by Western blot analysis using the ALK1 antibody. ALK activity in cells transfected with the functional NPM-ALK construct was confirmed using an antibody specific for phosphorylated ALK. Stable expression of functional NPM-ALK in HEK 293T cells resulted in JNK phosphorylation/activation, which was associated with phosphorylation of cJun at serine 73 and an increase in total c-Jun levels that is attributable to positive autoregulation of cJun transcription. Total JNK1 expression served as a protein loading control in this experiment. (B) Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with 50 μg of empty vector (pDest40), active NPM-ALK, or mutant, kinase-dead NPM-ALK (210K>R), and whole-cell lysates were prepared at 48 hours after transfection. Immunoblots showed that transient expression of the functional NPM-ALK in Jurkat cells resulted in a substantial increase of p-JNK, which was associated with increased phosphorylation of cJun. (C) To study the NPM-ALK–induced AP-1 transcriptional activity, Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter gene under the control of a promoter that contains 3 successive AP-1 specific binding sites (3×AP-Luc) together with an empty expression vector or expression plasmids encoding for the functional or kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK. Two sets of experiments were performed with or without cotransfection of a full-length cJun expression plasmid (pHA-cJun). After 48 hours the cells were collected to determine luciferase activity. The results showed an increase in relative luciferase units in cells expressing the functional NPM-ALK, indicating an increase in AP-1 transcriptional activity. The transcriptional activity was enhanced in Jurkat cells by coexpression of full-length cJun (right panel). The fold activation compared with the basal activity of the AP-1 promoter sites in cells transfected with the empty vector, which was set to 1. All measurements were performed in triplicate; bars indicate standard error. (D) Coimmunoprecipitaion studies were performed in SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells. Whole-cell lysates were first immunoprecipitated with JNK1, JNK2, or control IgG1 antibodies, and then immunoblotted using specific ALK antibody. Conversely, whole-cell lysates were also immunoprecipitated with ALK or control IgG1 antibodies and then immunoblotted using a JNK1/2 antibody that detects both JNK1 and JNK2. The same membrane was also probed with ALK antibody. The top 2 arrows show a specific band at 80 kDa (NPM-ALK), indicating that NPM-ALK physically interacts with JNK1 and JNK2 in ALK+ ALCL cells. The bottom arrow indicates detection of JNK1/2 by Western blot analysis after inverse coimmunoprecipitation that further confirmed the physical interaction between NPM-ALK and JNKs. Immunoglobulin heavy chain (HC) served as a loading control. (E) SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells were treated with the inhibitor WHI-P154 at concentrations (0, 0.5, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM), previously shown to inhibit JAK3 and ALK enzymatic activity. Whole-cell lysates were prepared at 24 hours after treatment. Immunoblots demonstrate that ALK phosphorylation is decreased at a concentration of 2.5 μm, and correlates with decreased phosphorylation (activation) of JNK. (F) Inhibition of ALK enzymatic activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells resulted in decreased AP-1 DNA binding activity in a concentration-dependent manner as shown by EMSA and autoradiography (black arrow). SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells were treated with the inhibitor WHI-P154 at concentrations of 0, 5, or 10 μM. After incubation for 24 hours, nuclear extracts were prepared and assessed by EMSA using double-stranded consensus AP-1 oligonucleotide. Free DNA (free probe, FP) is shown in the bottom of the gel.

NPM-ALK activates JNK and cJun and Induces AP-1 transcriptional activity. (A) HEK 293T cells were stably transfected with expression plasmids including empty vector (pDest40), active NPM-ALK, or mutant NPM-ALK (K210R) with a kinase-dead domain. Expression of NPM-ALK, in cells transfected with functional or kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK, was confirmed by Western blot analysis using the ALK1 antibody. ALK activity in cells transfected with the functional NPM-ALK construct was confirmed using an antibody specific for phosphorylated ALK. Stable expression of functional NPM-ALK in HEK 293T cells resulted in JNK phosphorylation/activation, which was associated with phosphorylation of cJun at serine 73 and an increase in total c-Jun levels that is attributable to positive autoregulation of cJun transcription. Total JNK1 expression served as a protein loading control in this experiment. (B) Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with 50 μg of empty vector (pDest40), active NPM-ALK, or mutant, kinase-dead NPM-ALK (210K>R), and whole-cell lysates were prepared at 48 hours after transfection. Immunoblots showed that transient expression of the functional NPM-ALK in Jurkat cells resulted in a substantial increase of p-JNK, which was associated with increased phosphorylation of cJun. (C) To study the NPM-ALK–induced AP-1 transcriptional activity, Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter gene under the control of a promoter that contains 3 successive AP-1 specific binding sites (3×AP-Luc) together with an empty expression vector or expression plasmids encoding for the functional or kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK. Two sets of experiments were performed with or without cotransfection of a full-length cJun expression plasmid (pHA-cJun). After 48 hours the cells were collected to determine luciferase activity. The results showed an increase in relative luciferase units in cells expressing the functional NPM-ALK, indicating an increase in AP-1 transcriptional activity. The transcriptional activity was enhanced in Jurkat cells by coexpression of full-length cJun (right panel). The fold activation compared with the basal activity of the AP-1 promoter sites in cells transfected with the empty vector, which was set to 1. All measurements were performed in triplicate; bars indicate standard error. (D) Coimmunoprecipitaion studies were performed in SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells. Whole-cell lysates were first immunoprecipitated with JNK1, JNK2, or control IgG1 antibodies, and then immunoblotted using specific ALK antibody. Conversely, whole-cell lysates were also immunoprecipitated with ALK or control IgG1 antibodies and then immunoblotted using a JNK1/2 antibody that detects both JNK1 and JNK2. The same membrane was also probed with ALK antibody. The top 2 arrows show a specific band at 80 kDa (NPM-ALK), indicating that NPM-ALK physically interacts with JNK1 and JNK2 in ALK+ ALCL cells. The bottom arrow indicates detection of JNK1/2 by Western blot analysis after inverse coimmunoprecipitation that further confirmed the physical interaction between NPM-ALK and JNKs. Immunoglobulin heavy chain (HC) served as a loading control. (E) SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells were treated with the inhibitor WHI-P154 at concentrations (0, 0.5, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM), previously shown to inhibit JAK3 and ALK enzymatic activity. Whole-cell lysates were prepared at 24 hours after treatment. Immunoblots demonstrate that ALK phosphorylation is decreased at a concentration of 2.5 μm, and correlates with decreased phosphorylation (activation) of JNK. (F) Inhibition of ALK enzymatic activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells resulted in decreased AP-1 DNA binding activity in a concentration-dependent manner as shown by EMSA and autoradiography (black arrow). SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells were treated with the inhibitor WHI-P154 at concentrations of 0, 5, or 10 μM. After incubation for 24 hours, nuclear extracts were prepared and assessed by EMSA using double-stranded consensus AP-1 oligonucleotide. Free DNA (free probe, FP) is shown in the bottom of the gel.

We next investigated whether NPM-ALK is capable of inducing AP-1 transcriptional activity as a result of JNK/cJun activation. Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter gene under control of a promoter that contains 3 successive AP-1 specific binding sites (3 × AP-Luc) together with an empty vector (pDest40), functional NPM-ALK, or kinase-dead mutant NPM-ALK (K210R). These experiments were performed with or without cotransfection of a full-length cJun expression plasmid (pHA-cJun). At 48 hours after transfection, a dramatic increase in relative luciferase units was observed in cells expressing functional NPM-ALK but not in cells expressing the mutant NPM-ALK (Figure 3C). The transcriptional activity was enhanced in Jurkat cells by coexpression of full-length cJun with functional NPM-ALK (Figure 3C, left).

To further demonstrate the biologic link between NPM-ALK and JNK, coimmunoprecipitation studies were performed that revealed that NPM-ALK physically interacts with JNK1 in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. Reverse coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed the physical interaction between NPM-ALK and JNK (Figure 3D). It is likely that NPM-ALK also interacts with other MAP kinases that operate upstream of JNKs.34 Next, NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells were treated with the inhibitor WHI-P154 previously shown to inhibit ALK enzymatic activity directly or indirectly.31,32 At 24 hours after treatment, decreased ALK phosphorylation was observed at the concentration of 2.5 μM or higher, which was linked to decreased phosphorylation of JNK (Figure 3E). Inhibition ALK enzymatic activity dramatically decreased AP-1 DNA binding activity as shown by EMSA using consensus AP-1 oligonucleotides, suggesting that AP-1 activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells is largely dependent on ALK-mediated activation of JNK/cJun (Figure 3F).

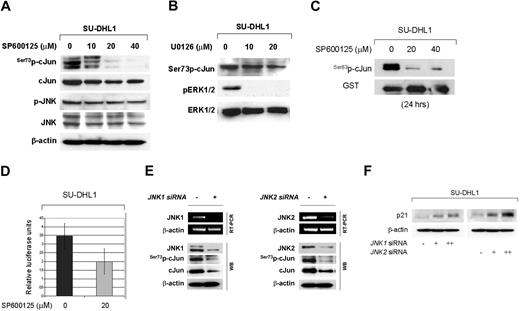

Serine 73 cJun phosphorylation is mediated by JNKs in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells

Transcriptional activity of cJun is stimulated by phosphorylation of serine residues in the N-terminal region. Members of the MAPK family such as JNKs and ERKs have been shown to be involved in cJun phosphorylation and transcriptional activation. To address the question whether JNK phosphorylates cJun at the N-terminal site in NPM-ALK+ ALCL, experiments were performed using a JNK inhibitor, SP600125,35 and specific JNK1/2 siRNA to selectively silence JNK1 or JNK2. As shown in Figure 4A, treatment of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells with SP600125 for 48 hours resulted in almost complete inhibition of serine 73 phosphorylation of cJun at a concentration of 20 μm/mL. Total cJun levels were also decreased to a lesser extent in a dose dependent manner, confirming an autoregulatory mechanism of cJun/AP-1 on its own promoter. When the inhibitor was used at high concentrations, partial inhibition of constitutively active phosphorylation of JNK was observed consistent with previously published data in other cell types35,36 (Figure 4A). Similar results were obtained at different time points including 24 and 36 hours after treatment (not shown). By contrast, under the same experimental conditions, treatment of ALCL cells with increasing concentrations of the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 effectively inhibited ERK1/2 phosphorylation but did not affect cJun phosphorylation (Figure 4B). These results confirm that neither ERK1 nor ERK2 phosphorylate cJun at its N-terminal site to promote its transcriptional activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells.

cJun phosphorylation is mediated by the JNK group of MAPKs in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) SU-DHL1 cells were treated with the specific JNK inhibitor, SP600125, at concentrations of 0, 10, 20, or 40 μM. Whole-cell lysates were prepared at 48 hours and immunoblots showed that inhibition of JNK activity resulted in decreased Ser73p-cJun levels in a dose-dependent manner. This decrease was detectable at a concentration of 10 μM, but it was more prominent at a concentration of 20 μM. A decrease in cJun protein level was also observed because of an autoregulatory mechanism of cJun on its own transcription. (B) Treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with U0126, a specific inhibitor of the MEK1/2 group of MAPK kinase, was performed at concentrations of 0, 10, and 20 μM. After incubation for 48 hours, whole-cell lystates were prepared and immunoblots showed decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, indicating sufficient ERK inactivation. However, this did not result in decreased cJun phosphorylation. These results suggest that JNKs, but not ERK, mediate cJun activation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL. (C) JNK activity was assessed using an in vitro kinase assay using GST-cJun as a substrate. SU-DHL1 cells were treated with the specific JNK inhibitor, SP600125, at concentrations of 0, 20, and 40 μM. After 24 hours of incubation, cells were collected and whole-cell lysates were prepared and incubated with the GST-cJun substrate. Immunoblots showed that inhibition of JNK activity is associated with decreased cJun phosphorylation in vitro. (D) SU-DHL1 cells were transfected with AP-1-Luc reporter plasmid and, after incubation for 24 hours, were treated with the specific JNK inhibitor SP600125 at concentrations of 0 and 20 μM. After 24 hours the cells were collected to determine luciferase activity. The graph shows a substantial decrease in AP-1 promoter activity after JNK inhibition. Bars indicate standard error. (E) To further investigate the role of JNK1/2 isoforms in cJun activation, SUDHL1 cells were transiently transfected with 20 μg of siRNA selectively targeting JNK1 or JNK2 gene products, and endogenous JNK1/JNK2 expression levels were confirmed by RT-PCR, as well as by Western blot analysis. Cells were harvested at 48 hours after transfection and mRNA and whole lysates were prepared. RT-PCR and immunoblots confirmed JNK1 or JNK2 silencing. cJun phosphorylation was decreased after knocking down JNK1 or JNK2 in immunoblots. (F) SU-DHL1 cells were transiently transfected with 0, 10, and 20 μg of JNK1 or JNK2 or control siRNA, and whole cell lysates were prepared at 48 hours after transfection. Immunoblots demonstrate upregulation of p21 protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner.

cJun phosphorylation is mediated by the JNK group of MAPKs in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) SU-DHL1 cells were treated with the specific JNK inhibitor, SP600125, at concentrations of 0, 10, 20, or 40 μM. Whole-cell lysates were prepared at 48 hours and immunoblots showed that inhibition of JNK activity resulted in decreased Ser73p-cJun levels in a dose-dependent manner. This decrease was detectable at a concentration of 10 μM, but it was more prominent at a concentration of 20 μM. A decrease in cJun protein level was also observed because of an autoregulatory mechanism of cJun on its own transcription. (B) Treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with U0126, a specific inhibitor of the MEK1/2 group of MAPK kinase, was performed at concentrations of 0, 10, and 20 μM. After incubation for 48 hours, whole-cell lystates were prepared and immunoblots showed decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, indicating sufficient ERK inactivation. However, this did not result in decreased cJun phosphorylation. These results suggest that JNKs, but not ERK, mediate cJun activation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL. (C) JNK activity was assessed using an in vitro kinase assay using GST-cJun as a substrate. SU-DHL1 cells were treated with the specific JNK inhibitor, SP600125, at concentrations of 0, 20, and 40 μM. After 24 hours of incubation, cells were collected and whole-cell lysates were prepared and incubated with the GST-cJun substrate. Immunoblots showed that inhibition of JNK activity is associated with decreased cJun phosphorylation in vitro. (D) SU-DHL1 cells were transfected with AP-1-Luc reporter plasmid and, after incubation for 24 hours, were treated with the specific JNK inhibitor SP600125 at concentrations of 0 and 20 μM. After 24 hours the cells were collected to determine luciferase activity. The graph shows a substantial decrease in AP-1 promoter activity after JNK inhibition. Bars indicate standard error. (E) To further investigate the role of JNK1/2 isoforms in cJun activation, SUDHL1 cells were transiently transfected with 20 μg of siRNA selectively targeting JNK1 or JNK2 gene products, and endogenous JNK1/JNK2 expression levels were confirmed by RT-PCR, as well as by Western blot analysis. Cells were harvested at 48 hours after transfection and mRNA and whole lysates were prepared. RT-PCR and immunoblots confirmed JNK1 or JNK2 silencing. cJun phosphorylation was decreased after knocking down JNK1 or JNK2 in immunoblots. (F) SU-DHL1 cells were transiently transfected with 0, 10, and 20 μg of JNK1 or JNK2 or control siRNA, and whole cell lysates were prepared at 48 hours after transfection. Immunoblots demonstrate upregulation of p21 protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner.

Using an in vitro kinase assay with cJun-GST as a substrate, JNK activity was assessed after treatment of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells with increasing concentrations of SP600125. At 24 hours after incubation, inhibition of JNK activity resulted in decreased cJun phosphorylation, further supporting the critical role of JNK in cJun activation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells (Figure 4C). In addition, inhibition of JNK activity with SP600125 reduced substantially AP-1 transcriptional activity assessed by a luciferase reporter assay (Figure 4D).

To further confirm that cJun phosphorylation is dependent on JNKs, JNK1 or JNK2 gene expression was selectively inhibited in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cell lines using specific siRNA. Adequate knocking down of JNK1 or JNK2 was confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis (Figure 4E). Transient transfection of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells with JNK1 or JNK2 siRNA resulted in decreased cJun phosphorylation linked to decreased total cJun expression (Figures 4E). Silencing of JNK1 or JNK2 genes also resulted in a concentration-dependent upregulation of p21, a transcriptional target of cJun (Figure 4F).

Inhibition of JNK activity induces cell-cycle arrest in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells

As shown in Figure 5A, inhibition of JNK activity in ALCL cells treated with SP600125 resulted in decreased cell growth in a dose-dependent manner. This effect of JNK inhibition was mostly attributed to cell-cycle arrest. Cell-cycle analysis demonstrated a dramatic decrease in the S-phase fraction from 23.4% in untreated cells to 4.4% in cells treated with 20 μM SP600125. These results were confirmed by BrdU incorporation studies using a colorimetric method (Figure 5B). Cell-cycle arrest was also associated with a more than 3-fold increase in the G2/M fraction, from 21.5% in untreated cells up to 70% in cells treated with 20 μM SP600125. (Figure 5B). In addition to cell-cycle changes, a 15% increase in apoptosis was also observed after treatment of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells with SP600125 (Figure S2A).

Inhibition of JNK activity reduces cell growth due to G2/M cell-cycle arrest in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) SU-DHL1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 μM) of SP600125. Inhibition of JNK activity resulted in decreased cell viability and proliferation of viable cells as assessed by trypan blue exclusion (left panel) and MTS assays (right panel), respectively. Data presented as the mean (± a standard deviation [SD]) in triplicate measurements. (B) The decrease in cell growth of SU-DHL1 cells, after treatment with the inhibitor SP600125 for 48 hours, was associated with cell-cycle arrest. The S-phase of the cell cycle was assessed by BrdU incorporation (left panel) and measured by a colorimetric assay. Results were expressed as percentage of cells in the S-phase of cell cycle (mean ± SD of triplicate measurements) compared with untreated cells. Cell-cycle analysis, assessed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (right panel), revealed a dramatic decrease in the S-phase fraction associated with a more than 3-fold increase of the G2/M fraction after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with 20 μM SP600125. (C) Western blot analysis after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with SP600125 at the same time point (48 hours) showed increased levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, a known cell-cycle regulator for transition to S and through G2 phase. In addition, increased levels of underphosphorylated retinoblastoma protein and decreased levels of cyclin A were observed in a dose-dependent manner.

Inhibition of JNK activity reduces cell growth due to G2/M cell-cycle arrest in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) SU-DHL1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 μM) of SP600125. Inhibition of JNK activity resulted in decreased cell viability and proliferation of viable cells as assessed by trypan blue exclusion (left panel) and MTS assays (right panel), respectively. Data presented as the mean (± a standard deviation [SD]) in triplicate measurements. (B) The decrease in cell growth of SU-DHL1 cells, after treatment with the inhibitor SP600125 for 48 hours, was associated with cell-cycle arrest. The S-phase of the cell cycle was assessed by BrdU incorporation (left panel) and measured by a colorimetric assay. Results were expressed as percentage of cells in the S-phase of cell cycle (mean ± SD of triplicate measurements) compared with untreated cells. Cell-cycle analysis, assessed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (right panel), revealed a dramatic decrease in the S-phase fraction associated with a more than 3-fold increase of the G2/M fraction after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with 20 μM SP600125. (C) Western blot analysis after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with SP600125 at the same time point (48 hours) showed increased levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, a known cell-cycle regulator for transition to S and through G2 phase. In addition, increased levels of underphosphorylated retinoblastoma protein and decreased levels of cyclin A were observed in a dose-dependent manner.

To investigate the mechanism underlying cell-cycle arrest, we next performed Western blot analysis to assess the levels of cell- cycle regulators. p21, a known transcriptional target of cJun, was shown to be upregulated after inhibition of cJun phosphorylation, contributing to cell-cycle arrest. There was a decrease in the expression level of cyclin A in a dose-dependent manner, while a slight decrease in cyclin D3 levels was observed. In addition, cell- cycle arrest was associated with downregulation of the underphosphorylated form of the Rb protein (Figure 5C). Similar changes in cell-cycle progression were observed after silencing of JNK1 or JNK2 gene products using specific siRNA, with upregulation of p21, the latter being more prominent after silencing JNK2 gene (Figure 4F). Knocking down JNK1 or JNK2 genes also resulted in increased apoptosis (Figure S2B).

These results suggest that in NPM-ALK+ ALCL, JNK activation promotes cell-cycle progression through regulation of cJun and its transcriptional target, p21.

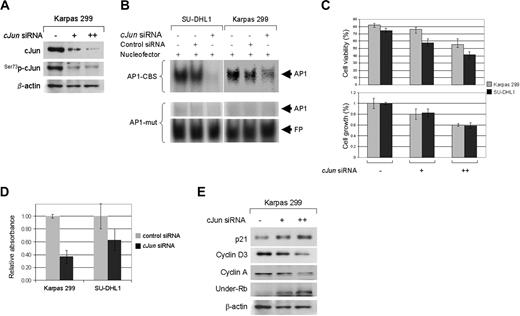

Silencing of cJun gene induces cell-cycle arrest through upregulation of p21

To investigate the significance of cJun overexpression in the growth of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells lines, we performed in vitro studies using specific siRNA to knock down the cJun gene. As shown in Figure 6A, transient transfection with cJun siRNA efficiently silenced cJun gene expression. Silencing of cJun gene was associated with a significant decrease of AP-1 binding activity as assessed by EMSA, which was more prominent in SU-DHL1 than Karpas 299 cells (Figure 6B).

Inhibition of cJun expression reduces cell growth in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells were transiently transfected with 10 μg or 20 μg (SU-DHL1) and 20 μg or 40 μg (Karpas 299) cJun or control siRNA, and whole-cell lysates from both cell lines were prepared at 48 hours after transfection. Western blot analysis showed that endogenous cJun was almost completely silenced when 40μg siRNA was used. As expected, decreased levels of Ser73p-cJun were also observed. (B) Silencing of cJun gene expression in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells resulted in decreased AP-1 DNA binding activity as shown by EMSA and autoradiography (first row, black arrow). SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells were transiently transfected with 20μg c-Jun siRNA. After incubation for 48 hours, nuclear extracts were prepared and assessed by EMSA using double-stranded consensus AP-1 oligonucleotide. Mutant AP-1 oligonucleotide served as a negative control (second row). Free probe (FB, DNA oligonucletides) is shown in the bottom panel. (C) Selective silencing of cJun gene expression resulted in decreased cell viability (top panel) and a more prominent decrease in proliferation of viable cells (bottom panel) as assessed by trypan blue exclusion and MTS assays, respectively. The data presented are the mean (± SD) in triplicate measurements. (D) Reduced cell proliferation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells is attributable to cell-cycle arrest, because cJun silencing also resulted in decreased S-phase fraction evaluated by BrdU incorporation studies. Results have been normalized to those of control siRNA samples. (E) Western blot analysis after transient transfection of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells with specific cJun siRNA showed upregulation of p21 and underphosphorylated Rb in a concentration-dependent fashion, as well as downregulation of cyclin A and cyclin D3.

Inhibition of cJun expression reduces cell growth in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells were transiently transfected with 10 μg or 20 μg (SU-DHL1) and 20 μg or 40 μg (Karpas 299) cJun or control siRNA, and whole-cell lysates from both cell lines were prepared at 48 hours after transfection. Western blot analysis showed that endogenous cJun was almost completely silenced when 40μg siRNA was used. As expected, decreased levels of Ser73p-cJun were also observed. (B) Silencing of cJun gene expression in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells resulted in decreased AP-1 DNA binding activity as shown by EMSA and autoradiography (first row, black arrow). SU-DHL1 and Karpas 299 cells were transiently transfected with 20μg c-Jun siRNA. After incubation for 48 hours, nuclear extracts were prepared and assessed by EMSA using double-stranded consensus AP-1 oligonucleotide. Mutant AP-1 oligonucleotide served as a negative control (second row). Free probe (FB, DNA oligonucletides) is shown in the bottom panel. (C) Selective silencing of cJun gene expression resulted in decreased cell viability (top panel) and a more prominent decrease in proliferation of viable cells (bottom panel) as assessed by trypan blue exclusion and MTS assays, respectively. The data presented are the mean (± SD) in triplicate measurements. (D) Reduced cell proliferation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells is attributable to cell-cycle arrest, because cJun silencing also resulted in decreased S-phase fraction evaluated by BrdU incorporation studies. Results have been normalized to those of control siRNA samples. (E) Western blot analysis after transient transfection of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells with specific cJun siRNA showed upregulation of p21 and underphosphorylated Rb in a concentration-dependent fashion, as well as downregulation of cyclin A and cyclin D3.

Incubation of NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells with cJun siRNA resulted in decreased cell growth in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6C). As observed with the JNK inhibitor, there was a significant decrease in the S-phase of Karpas 299 and SU-DHL1 cells transiently transfected with cJun siRNA compared with control cells (Figure 6D).

Western blot analysis demonstrated that silencing the cJun gene was associated with increased levels of p21, and down-regulation of cyclin A (Figure 6E). These results suggest that cJun promotes cell-cycle progression in ALCL, predominantly by regulating the G2/M checkpoint. In addition, cyclin D3 levels were decreased after knocking down cJun.

NPM-ALK promotes cell-cycle progression through activation of JNK/cJun signaling in NPM-ALK+ ALCL. ALCL frequently carries the chromosomal translocation t(2;5)(p23;q35), resulting in aberrant expression of NPM-ALK. NPM-ALK has been shown to be oncogenic through activation of a number of cell- signaling pathways. This study reveals another oncogenic pathway, JNK/cJun, that is constitutively activated by the NPM-ALK fusion kinase. The JNKs, members of the MAPK superfamily, have been shown to play a role in cell proliferation and transformation. Activation of JNK, through phosphorylation by 2 distinct MAPK kinases, MAPK kinase 4 and MAPK kinase 7, mediates phosphorylation of cJun, the best-characterized transcription factor of the AP-1 family. Phosphorylation of cJun by JNK is essential for stimulation of its transcriptional activity and its growth-promoting effects. The latter can be mediated through regulation of a number of cell-cycle- controlling genes including the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, which operates at both the G1/S and G2/M checkpoints. Taken together, our data suggest that the NPM-ALK–induced activation of JNK/cJun signaling may lead to uncontrolled cell-cycle progression and cell proliferation, thus contributing to oncogenesis of NPM-ALK+ ALCL.

NPM-ALK promotes cell-cycle progression through activation of JNK/cJun signaling in NPM-ALK+ ALCL. ALCL frequently carries the chromosomal translocation t(2;5)(p23;q35), resulting in aberrant expression of NPM-ALK. NPM-ALK has been shown to be oncogenic through activation of a number of cell- signaling pathways. This study reveals another oncogenic pathway, JNK/cJun, that is constitutively activated by the NPM-ALK fusion kinase. The JNKs, members of the MAPK superfamily, have been shown to play a role in cell proliferation and transformation. Activation of JNK, through phosphorylation by 2 distinct MAPK kinases, MAPK kinase 4 and MAPK kinase 7, mediates phosphorylation of cJun, the best-characterized transcription factor of the AP-1 family. Phosphorylation of cJun by JNK is essential for stimulation of its transcriptional activity and its growth-promoting effects. The latter can be mediated through regulation of a number of cell-cycle- controlling genes including the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, which operates at both the G1/S and G2/M checkpoints. Taken together, our data suggest that the NPM-ALK–induced activation of JNK/cJun signaling may lead to uncontrolled cell-cycle progression and cell proliferation, thus contributing to oncogenesis of NPM-ALK+ ALCL.

Discussion

Accumulating evidence over the past few years suggests that the NPM-ALK fusion kinase mediates its effects, at least in part, through activation of oncogenic pathways, such as JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/mTOR, Ras/MEK/ERK, and perhaps other mechanisms that ultimately lead to apoptosis inhibition or uncontrolled cell-cycle progression.3,4,7-15 Because ALCL tumor cells are highly proliferative,37 deregulation of mechanisms controlling cell-cycle progression are likely to contribute to its pathogenesis. Supportive of this hypothesis are previous studies that have shown aberrant expression or inactivation of cell-cycle regulatory proteins in ALCL tumors, including p27, Rb, and cyclin D3.38-40 In this study, we hypothesized that NPM-ALK phosphorylates/activates JNK, which in turn activates cJun via phosphorylation of serine residues at its transactivation domain. cJun activation may result in increased cJun transcriptional activity on target cell-cycle regulatory genes.

cJun transcription factor, a well-characterized component of the homodimeric or heterodimeric AP-1 complex, has been recognized as a positive regulator of cell growth. Previous studies have shown that mice lacking cJun die at midgestational age with impaired hepatogenesis,19 whereas cJun-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts have marked proliferation defects and undergo premature senescence in vitro.41,42 In addition to those physiologic functions in normal development and cell proliferation, cJun has been implicated in the transformation of mammalian cell lines43 and the development of skin and liver tumors in mice.44,45 Phosphorylation of cJun at serine 63 and serine 73 residues of the N-terminal domain by JNKs46 is critical for stimulation of cJun activity and oncogenic transformation.24,43,47 In turn, JNKs can be activated through phosphorylation by 2 upstream MAPK kinases, MAPK kinase 4 and MAPK kinase 7.

Using vectors expressing functional and inactive (kinase-dead) NPM-ALK in 2 different cell systems (HEK 293T and Jurkat), we showed here for the first time that NPM-ALK oncogenic kinase is capable of phosphorylating/activating JNK, which phosphorylates its substrate cJun at the critical serine-73 residue. As a result, cJun becomes activated and upregulated at the transcriptional level via a well-established autoregulatory positive feedback loop that ultimately leads to increased cJun/AP-1 DNA binding and transcriptional activity. Conversely, inhibition of ALK activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells decreases JNK phosphorylation and AP-1 DNAbinding activity in a concentration-dependent manner. cJun is phosphorylated at serine 73 by JNKs in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells, because pharmacologic inhibition of JNK activity or silencing JNK1 or JNK2 genes dephosphorylated cJun. Interestingly, in a previous study, transgenic expression of NPM-ALK under the control of a Vav promoter produced murine lymphomas with hyperactive JNK by up to 30-fold compared with sIgM-stimulated primary B-cells, suggesting a critical role of JNK activation in NPM-ALK–mediated lymphomagenesis in vivo.48 Inhibition of other members of the MAPK family involved in cJun phosphorylation, such as ERK1 and ERK2,49 did not affect Ser73pcJun levels in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells in our study, in accordance with published data in B-cell lymphoma cells.36

Consistent with our in vitro data showing NPM-ALK–mediated activation of JNK signaling, high expression levels of p-JNK and Ser73p-cJun were found in tumor cells of patients with NPM-ALK+ ALCL. Mathas et al28 previously have reported high AP-1 activity and frequent overexpression of cJun protein in Hodgkin lymphoma and ALCL cells. In a recent study, using a large number (n = 332) of lymphoproliferative disorders, including Hodgkin lymphomas, and B-cell or T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas of various histologic types, we showed that cJun expression and phosphorylation were restricted to CD30+ tumors.30 However, the percentage of Ser73p-cJun+ and total cJun+ tumor cells varied remarkably among different histologic types. For instance, cJun expression and phosphorylation levels were significantly higher in ALK+ than ALK-ALCL,30 further supporting the data in this study and suggesting that activation of JNK signaling is largely dependent on NPM-ALK activity in ALCL.

Other chromosomal translocations of certain leukemia types, such as chronic myelogenous leukemia or acute myeloid leukemia, also have been shown to induce cell proliferation and oncogenic transformation through upregulation of cJun. For instance, BCR-ABL, AML1/Evi-1, or AML1-ETO fusion proteins are capable of activating JNK signaling and enhance AP-1 activity.50-54 In addition, recent studies provide evidence that JNK signaling is activated and promotes cell proliferation in non–small-cell lung carcinoma and glioblastoma cells, further supporting the emerging role of JNKs in tumorigenesis.55,56

Furthermore, we investigated the biologic effects of constitutive activation of JNK and cJun in NPM-ALK+ ALCL. Inhibition of JNK activity using a specific JNK inhibitor, SP00125, or knocking down JNK1 or JNK2 genes by selective siRNAs, de-phosphorylated cJun and arrested NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells at G2/M phase. The latter effect can be attributed to p21 upregulation, a transcriptional target of cJun. It has been shown previously that JNK/cJun signaling is required to promote proliferation in primary murine embryonic fibroblasts.42,57 In addition, treatment of human B lymphoma cells with SP600125 predominantly led to G2/M growth arrest with fewer apoptotic cells (cells in subG1 phase) in a recent report.36 Similar results have been reported for multiple myeloma, erythroleukemia, and breast cancer cells.58,59 cJun can stimulate cell cycle progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle by a mechanism that involves direct transcriptional control of the cyclin D1 gene.20,22 Furthermore, cJun also decreases the transcription of negative regulators of cell-cycle progression, such as the tumor suppressor p53 and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21.17 We show that in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells, the growth promoting activity of JNK/cJun signaling is mostly mediated through regulation of molecules controlling cell-cycle progression at the G2/M checkpoint.

To further study the biologic effects of cJun overexpression in NPM-ALK+ ALCL, cJun gene was selectively silenced using specific siRNA. Of note, silencing the c-Jun gene significantly reduced AP-1 DNA binding as assessed by EMSA, suggesting that cJun is largely present in the AP-1 complexes in NPM-ALK+ ALCL. However, it is likely that other AP-1 transcription factors such as JunB or members of the Fos family28,60 may contribute to AP-1 activity in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells, as indicated by the partial inhibition of AP-1 DNA binding in Karpas 299 cells after knocking down cJun. Silencing of cJun led to a concentration-dependent decrease of cell growth associated with a similar decrease in the S-phase fraction of cell cycle. Again, cell-cycle arrest was linked to p21 up-regulation and, additionally, downregulation of cyclin A that operates at the G2/M checkpoint. Interestingly, cJun silencing also down-regulated cyclin D3, a known AP-1 target gene,61 which was previously shown to be expressed at higher mRNA and protein levels in ALK+ than ALK-ALCL.40,62

In summary, our data reveal a novel function of NPM-ALK oncogenic kinase, activation of JNK and its downstream signaling, which appears to critically contribute to cell proliferation in NPM-ALK+ ALCL through regulation of cell-cycle progression (Figure 7). Our results suggest that pharmacologic inhibition of JNK/cJun activity or targeting JNK1/2 and cJun genes by gene therapy approaches represent new investigational treatment options for patients with NPM-ALK+ ALCL.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

V.L. performed experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. E.D. performed experiments. L.J.M., M.S.L., K.S.E.-J., and F.X.C. contributed vital reagents and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. G.Z.R. designed experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: George Z. Rassidakis, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Hematopathology, Unit 54, The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: gzrassidakis@mdanderson.org.

![Figure 5. Inhibition of JNK activity reduces cell growth due to G2/M cell-cycle arrest in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) SU-DHL1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 μM) of SP600125. Inhibition of JNK activity resulted in decreased cell viability and proliferation of viable cells as assessed by trypan blue exclusion (left panel) and MTS assays (right panel), respectively. Data presented as the mean (± a standard deviation [SD]) in triplicate measurements. (B) The decrease in cell growth of SU-DHL1 cells, after treatment with the inhibitor SP600125 for 48 hours, was associated with cell-cycle arrest. The S-phase of the cell cycle was assessed by BrdU incorporation (left panel) and measured by a colorimetric assay. Results were expressed as percentage of cells in the S-phase of cell cycle (mean ± SD of triplicate measurements) compared with untreated cells. Cell-cycle analysis, assessed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (right panel), revealed a dramatic decrease in the S-phase fraction associated with a more than 3-fold increase of the G2/M fraction after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with 20 μM SP600125. (C) Western blot analysis after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with SP600125 at the same time point (48 hours) showed increased levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, a known cell-cycle regulator for transition to S and through G2 phase. In addition, increased levels of underphosphorylated retinoblastoma protein and decreased levels of cyclin A were observed in a dose-dependent manner.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/110/5/10.1182_blood-2006-11-059451/6/m_zh80140704800005.jpeg?Expires=1765914848&Signature=qI0hF31r~6iXMeOgwMy5n7pflzyf8moDBsFDlkNDEsKR1ocx4H1zga5znFpqmFEXzQnI08M96zhgNPoFRQALmP5eHf66NQFazPLwHKuHR7sZABBghDcU20GAtm481VG7G2ogUnSsXgX78Kw1~-qELQ~RobhKhtmf92jN66nYAeR1Q7YQjyd-5nBi~gN9oFbYBUxvzXXVcuDy~qF9ye2RRHXV8t7NBg8pZPad4EwvhHDNaMmvz6rzdQfylmzSmcYtWymU375yV2Sy-8Q9Ep85zW2rjkPGbFCJGg2Gzl1cL0Ip5Uvz2A2gpEXXNG4OrGwvunT7acI4qDuxpU4Xg0dHTg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Inhibition of JNK activity reduces cell growth due to G2/M cell-cycle arrest in NPM-ALK+ ALCL cells. (A) SU-DHL1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 μM) of SP600125. Inhibition of JNK activity resulted in decreased cell viability and proliferation of viable cells as assessed by trypan blue exclusion (left panel) and MTS assays (right panel), respectively. Data presented as the mean (± a standard deviation [SD]) in triplicate measurements. (B) The decrease in cell growth of SU-DHL1 cells, after treatment with the inhibitor SP600125 for 48 hours, was associated with cell-cycle arrest. The S-phase of the cell cycle was assessed by BrdU incorporation (left panel) and measured by a colorimetric assay. Results were expressed as percentage of cells in the S-phase of cell cycle (mean ± SD of triplicate measurements) compared with untreated cells. Cell-cycle analysis, assessed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (right panel), revealed a dramatic decrease in the S-phase fraction associated with a more than 3-fold increase of the G2/M fraction after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with 20 μM SP600125. (C) Western blot analysis after treatment of SU-DHL1 cells with SP600125 at the same time point (48 hours) showed increased levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, a known cell-cycle regulator for transition to S and through G2 phase. In addition, increased levels of underphosphorylated retinoblastoma protein and decreased levels of cyclin A were observed in a dose-dependent manner.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/110/5/10.1182_blood-2006-11-059451/6/m_zh80140704800005.jpeg?Expires=1766172300&Signature=JhmHa42V9vfajBZX~G8zaWvNslbEyGqZ4tL-bwUw~B4C~i0w6FWG-DS5xIMFo4dm4fSkUZl1T1pHGX8ulTMOK2WhW3fcauTzIwF543UkYFSqlG0xXpqkq67R0TnHYmyfa9mqGjts00I8VaZIn1UVMSnSEySIrJ6TAvqReIuG408sN4W5bSOZTocf3KTgFpKpL83bcHw1y2hN0S9CFpJHAhKCCUoPpweD6jBgylq8U6MQ0F-4mhbY1Vei6k5i76ldp6axnr6o6xuMZnoIjNEIf2LBO4xOh-afSzvigz3knQae83Ckz2b4VBgjl9f3eBnsgh-uz5fV~WUP-S~Z-FLfzg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)