Members of the T-cell immunoglobulin– and mucin-domain–containing molecule (TIM) family have roles in T-cell–mediated immune responses. TIM-1 and TIM-2 are predominantly expressed on T helper type 2 (Th2) cells, whereas TIM-3 is preferentially expressed on Th1 and Th17 cells. We found that TIM-1 and TIM-3, but neither TIM-2 nor TIM-4, were constitutively expressed on mouse peritoneal mast cells and bone marrow–derived cultured mast cells (BMCMCs). After IgE + Ag stimulation, TIM-1 expression was down-regulated on BMCMCs, whereas TIM-3 expression was up-regulated. We also found that recombinant mouse TIM-4 (rmTIM-4), which is a ligand for TIM-1, as well as an anti–TIM-3 polyclonal Ab, can promote interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-6, and IL-13 production without enhancing degranulation in BMCMCs stimulated with IgE + Ag. Moreover, the anti–TIM-3 Ab, but neither anti–TIM-1 Ab nor rmTIM-4, suppressed mast-cell apoptosis. These observations suggest that TIM-1 and TIM-3 may be able to influence T-cell–mediated immune responses in part through effects on mast cells.

Introduction

Molecules of the TIM family are thought to contribute to the development of autoimmune and allergic diseases by modulating T-cell function,1,,–4 and genetic polymorphism affecting these molecules may also play a role in such disorders.1,,–4

TIM-1 enhances and TIM-2 suppresses T helper type 2 (Th2) cell activation, and TIM-3 down-regulates Th1 cell function.1,–3 Such effects are likely to be important. Thus, mice treated with an anti–TIM-1 Ab or a TIM-1 extracellular domain protein exhibited attenuated development of antigen-induced airway inflammation5 and of contact or delayed-type hypersensitivity responses6 ; administration of TIM-2–Ig to mice ameliorated development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,7 whereas TIM-2–deficient mice exhibited exacerbated airway inflammation8 ; and blockade of the TIM-3 pathway exacerbated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,9 diabetes (in nonobese diabetic mice),10 and acute graft-versus-host disease.11

Mast cells are important effector cells in host defense, and they also contribute to the development of autoimmune and allergic diseases.12 In this study, we examined mouse mast cells for the expression of TIM family members and investigated whether such TIM expression by mast cells is functionally significant.

Materials and methods

Animal protocols were approved by the Stanford Administrative Panels on Laboratory Animal Care.

Mice and BMCMCs

C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice, and C57BL/6Ka and BALB/cKa mice were from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and the Stanford Animal Facility, respectively. Bone marrow–derived cultured mast cells (BMCMCs) were obtained by culturing mouse bone marrow cells in WEHI-3–conditioned medium (containing interleukin-3 [IL-3]) for 4 to 6 weeks, at which time more than 98% of the cells were identified as mast cells by flow cytometry for c-Kit and FcϵRI.

Reagents and Abs

rmIL-3, rmTIM-1, rmTIM-4, mouse mAbs for TIM-1 (222414) and TIM-3 (215015) and polyclonal Abs (pAbs) for TIM-1, TIM-3, and TIM-4 were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti–mouse TIM-3 mAb (8B.2C12), mTIM-1–Ig, and mTIM-3–Ig were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Anti–mouse TIM-1 (RMT1-4 and RMT1-17), TIM-2 (RMT2-1 and RMT2-14) (Figure S1; available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), and TIM-3 (RMT3-23)11 mAbs (currently available from eBioscience or BioLegend, San Diego, CA) were from H.A. Anti–mouse TIM-1 (3B3)13 and TIM-4 (21H12) (Figure S2) were from D.T.U. and R.H.D. Either mAbs or pAbs for TIM-1 or TIM-3 from R&D Systems showed bands (70-80 kDa) in Western blots of whole lysates from naive BMCMCs; by contrast, we found that RMT1-4, RMT1-17, RMT3-23, and 3B3 were not appropriate for Western blot analyses (Figure S3).

Flow cytometry, β-hexosaminidase release assay, and cytokine ELISAs

BMCMCs were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE (H1-ϵ-26, at 10 μg/mL)14 at 37°C overnight and then washed. Naive or IgE-sensitized BMCMCs were cultured with 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 ± 20 ng/mL DNP-human serum albumin (DNP-HSA [Ag]; Sigma, St Louis, MO) at 37°C for 1 hour (β-hexosaminidase release assay), 6 hours (for fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS] and enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assays [ELISAs]) or for 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 days (for apoptosis). FACS analysis15 and β-hexosaminidase release assay16 were performed as described. We used the Apoptosis Detection Kit and Bcl-2 Set (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for annexin V staining and Bcl-2 expression. Cytokine levels in supernatants were measured by Mouse IL-3, IL-4, and IL-6 BD OptEIA ELISA sets (BD PharMingen) and Mouse IL-13 DuoSets (R&D Systems).

Statistics

The unpaired Student t test, 2-tailed, was used for statistical evaluation of the results; unless otherwise specified, results are shown as mean plus or plus or minus standard deviation (SD) (n = 3/group).

Results and discussion

Expression of TIM family members on mouse mast cells

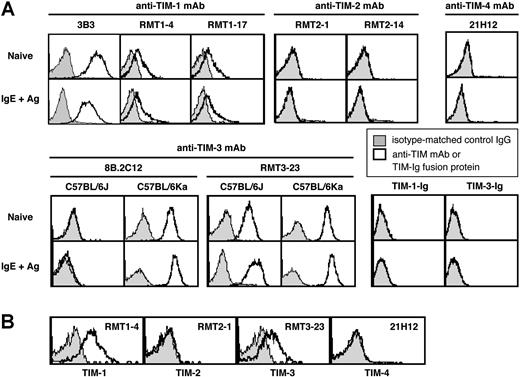

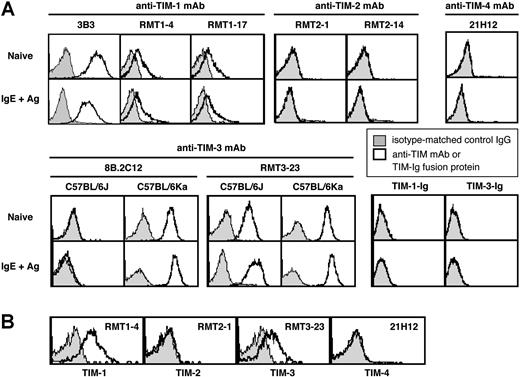

TIM molecules exhibit splicing variants in several mouse strains.1,–3 We therefore evaluated the expression of TIM family members using different mAbs for TIMs. Naive BMCMCs from C57BL/6J mice constitutively expressed TIM-1, as detected by anti–TIM-1 mAbs (3B3, RMT1-4, or RMT1-17) (Figure 1A). TIM-1 expression appeared to be slightly decreased 6 hours after IgE + Ag stimulation (Figure 1A). Little or no TIM-2 or TIM-4 expression was detectable on naive or IgE + Ag–stimulated C57BL/6J BMCMCs (Figure 1A), whereas TIM-2 expression was observed on Th2 cells (data not shown). TIM-1 or TIM-3 ligands were not detectable using TIM-1–Ig and TIM-3–Ig fusion proteins, either on naive or IgE + Ag–stimulated C57BL/6J BMCMCs (Figure 1A). Similar results were obtained with C57BL/6Ka, BALB/cJ, or BALB/cKa BMCMCs (data not shown).

Expression of TIM family members on mouse mast cells. (A) Expression of TIM-1, TIM-2, TIM-3, and TIM-4 and of TIM-1 and TIM-3 ligands on naive or IgE + Ag–stimulated c-Kit+ FcϵRIα+ BMCMCs derived from C57BL/6J or (for TIM-3) C57BL/6Ka mice. (B) Expression of TIM-1, TIM-2, TIM-3, and TIM-4 on peritoneal c-Kit+ FcϵRIα+ mast cells from C57BL/6J mice. Results in panels A and B are representative of similar results that were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

Expression of TIM family members on mouse mast cells. (A) Expression of TIM-1, TIM-2, TIM-3, and TIM-4 and of TIM-1 and TIM-3 ligands on naive or IgE + Ag–stimulated c-Kit+ FcϵRIα+ BMCMCs derived from C57BL/6J or (for TIM-3) C57BL/6Ka mice. (B) Expression of TIM-1, TIM-2, TIM-3, and TIM-4 on peritoneal c-Kit+ FcϵRIα+ mast cells from C57BL/6J mice. Results in panels A and B are representative of similar results that were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

Frisancho-Kiss et al17 reported that BALB/cJ mouse peritoneal mast cells (PMCs) constitutively express TIM-3, based on staining with the 8B.2C12 anti–TIM-3 mAb. Using the RMT3-23 anti–TIM-3 mAb, we detected constitutive expression of TIM-3 on C57BL/6J, C57BL/6Ka, BALB/cJ, or BALB/cKa BMCMCs (Figure 1A; data not shown). By contrast, when we used the 8B.2C12 anti–TIM-3 mAb, we detected TIM-3 expression on C57BL/6Ka, BALB/cJ, and BALB/cKa BMCMCs but not on C57BL/6J BMCMCs (Figure 1A; data not shown), because the 8B.2C12 antibody does not recognize the TIM-3 allele expressed in the C57BL/6J background.

Expression of TIM-3 on C57BL/6J, C57BL/6Ka, BALB/cJ, or BALB/cKa BMCMCs was increased slightly 6 hours after IgE +Ag stimulation (Figure 1A; data not shown). Constitutive expression of TIM-1 and TIM-3, but not TIM-2 and TIM-4, also was observed on PMCs from C57BL/6J mice (Figure 1B) and from C57BL/6Ka, BALB/cJ, and BALB/cKa mice (data not shown).

TIM-1 and TIM-3 can enhance mast cell–Th2 cytokine production

Interactions between TIM-1 on Th2 cells and TIM-4 on dendritic cells can enhance Th2-cell function,13,18 whereas administration of anti–TIM-1 Ab attenuated a Th2-associated mouse model of allergic airway inflammation.5 We searched for effects of TIMs on degranulation and/or Th2-associated cytokine production in naive, IgE-sensitized, or IgE-sensitized and Ag-stimulated BMCMCs.

Neither anti–TIM-1 pAbs nor mAbs (RMT1-4, RMT1-17, 3B3, or 222414), rmTIM4 nor anti–TIM-3 pAbs or mAbs (RMT3-23, 8B.2C11, or 215015) detectably influenced degranulation or phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK, or MAPK after IgE and Ag stimulation in any of the C57BL/6J BMCMCs tested (Figure 2A; Figure S4; data not shown). By contrast, rmTIM-4 slightly, but significantly, enhanced production of IL-4, IL-6, and IL-13, but it did not detectably influence IL-17 or IFN-γ production (data not shown), by IgE + Ag–stimulated C57BL/6J BMCMCs but not by naive or IgE-sensitized cells (Figure 2B-C). The effects of rmTIM-4 were enhanced by treatment with anti–TIM-4 pAb (Figure 2D) and inhibited by rmTIM-1 (Figure 2E). Anti–TIM-1 mAbs (3B3, RMT1-4, and RMT1-17) can enhance Th2-cell activation13 or modulate B-cell function (H.A., unpublished observations, November 2006) but not mast-cell activation (our results). These findings support the possibility that mAbs for TIM-1 may have distinct effects on different cell types.19 Our results suggest that interfering with TIM-1–TIM-4 interactions on mast cells, as well as blocking effects of TIM-4 on Th2 cells, may have therapeutic benefit in Th2-type disorders.

Effect of anti–TIM-1, anti–TIM-3, or rmTIM-4 on mast-cell function. C57BL/6J BMCMCs were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE (H1-ϵ-26) at 37°C overnight and then washed. Naive or IgE-sensitized C57BL/6J BMCMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of Ag (DNP-HSA, 20 ng/mL) together with (A) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 1 hour for β-hexosaminidase (β-Hex) release assay (P +I = PMA [0.1 μg/mL] + Ionomycin [1.0 μg/mL]); (B) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production; (C) 0 to 100 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (D) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 80 μg/mL anti–TIM-4 pAb or control IgG (goat IgG) at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE-sensitized cells ± Ag; (E) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 0 to 40 μg/mL rmTIM-1 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (F) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 days in the absence of IL-3 for apoptosis (the same data for culture with IL-3, rat IgG and goat IgG, or without any reagents [medium] are shown in the top and bottom panels for each group of BMCMCs); (G) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days for IL-3 production; (H,I) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days in the absence of IL-3 for Bcl-2 expression (the FACS data shown are representative of those obtained in 3 experiments using 3 different batches of BMCMCs). Top numbers indicate MFI for anti–Bcl-2 mAb staining; bottom numbers, MFI for control IgG staining. “IL-3” indicates results for BMCMCs maintained in IL-3–containing WEHI-3 cell-conditioned medium. (A-G, I) *P < .05 versus corresponding values for cells cultured with control IgG (B,D,F,G) or with no rmTIM-4 or rmTIM-1 (0 μg/mL) (C,E). Data shown in panels A to G and I are the average ± SEM (n = 3) of duplicate values for each condition obtained from an experiment done using 3 different batches of BMCMCs; such experiments were done 2 to 4 times each, and each of these gave similar results.

Effect of anti–TIM-1, anti–TIM-3, or rmTIM-4 on mast-cell function. C57BL/6J BMCMCs were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE (H1-ϵ-26) at 37°C overnight and then washed. Naive or IgE-sensitized C57BL/6J BMCMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of Ag (DNP-HSA, 20 ng/mL) together with (A) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 1 hour for β-hexosaminidase (β-Hex) release assay (P +I = PMA [0.1 μg/mL] + Ionomycin [1.0 μg/mL]); (B) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production; (C) 0 to 100 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (D) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 80 μg/mL anti–TIM-4 pAb or control IgG (goat IgG) at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE-sensitized cells ± Ag; (E) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 0 to 40 μg/mL rmTIM-1 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (F) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 days in the absence of IL-3 for apoptosis (the same data for culture with IL-3, rat IgG and goat IgG, or without any reagents [medium] are shown in the top and bottom panels for each group of BMCMCs); (G) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days for IL-3 production; (H,I) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days in the absence of IL-3 for Bcl-2 expression (the FACS data shown are representative of those obtained in 3 experiments using 3 different batches of BMCMCs). Top numbers indicate MFI for anti–Bcl-2 mAb staining; bottom numbers, MFI for control IgG staining. “IL-3” indicates results for BMCMCs maintained in IL-3–containing WEHI-3 cell-conditioned medium. (A-G, I) *P < .05 versus corresponding values for cells cultured with control IgG (B,D,F,G) or with no rmTIM-4 or rmTIM-1 (0 μg/mL) (C,E). Data shown in panels A to G and I are the average ± SEM (n = 3) of duplicate values for each condition obtained from an experiment done using 3 different batches of BMCMCs; such experiments were done 2 to 4 times each, and each of these gave similar results.

TIM-3 is expressed on Th19 and Th1720 cells, and either TIM-3 or galectin-9, a ligand for TIM-3, can negatively regulate Th1-cell function by inducing apoptosis.21 We found that anti–TIM-3 pAb, but not anti–TIM-3 mAbs (RMT3-23, 8B.2C12, or 215015), significantly enhanced IL-4, IL-6, and IL-13 production by IgE + Ag–stimulated BMCMCs (Figure 2B). The anti–TIM-3 pAb also slightly promoted IL-13, but not IL-6 and IL-4, production by naive and IgE-sensitized C57BL/6J BMCMCs in the absence of IgE + Ag (Figure 2B). These effects of anti–TIM-3 pAb could not be blocked by preincubation of BMCMCs with any of the anti–TIM-3 mAbs (data not shown).

The anti–TIM-3 pAb, but not other TIM-1 or TIM-3 Abs, also significantly inhibited IL-3 withdrawal-induced apoptosis of IgE-sensitized BMCMCs with or without exposure to Ag, as assessed by annexin V staining (Figure 2F) or trypan blue exclusion (data not shown). Anti–TIM-3 pAb also promoted IL-3 production, but not Bcl-2 expression, in BMCMCs (Figure 2G-I).

Results similar to those in Figure 2 were also obtained in BALB/cJ BMCMCs (data not shown). Our results are consistent with results of in vivo studies,9,–11 in which anti–TIM-3 mAbs (RMT3-23 or 8B.2C12) functioned as blocking Abs, whereas anti–TIM-3 pAb had agonist effects.

Our data show that mouse mast cells can constitutively express TIM-1 and TIM-3, but they do not detectably express TIM-2 or TIM-4. Moreover, in contrast to evidence that TIM-3 can negatively regulate Th1 cells, our findings indicate that, in mast cells, TIM-3 can enhance IgE + Ag–dependent cytokine secretion and survival. These observations raise the possibility that TIM-1 or TIM-3 or both can influence the development of autoimmune and allergic disorders at least in part through effects on mast cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fu-Tong Liu (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA) and David H. Katz (Medical Biology Institute, La Jolla, CA) for H1-ϵ-26 anti-DNP IgE-mAb–producing hybridoma cells, and members of the Galli laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the US Public Health Service (grants AI-23990, CA-72074, and HL-67674 to S.J.G.; and grants PO1AI-54456 and HL69507 to R.D.K. and D.T.U.); the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (H.A.); and the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (grant ID 05–24 to H.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.N. and S.J.G. designed research; S.N. and M.I. performed research; H. Suto, H.A., D.T.U., and R.H.D. provided reagents; S.N., M.I., H. Suto, H.A., D.T.U., R.H.D., H. Saito, and S.J.G. analyzed data; S.N., M.I., H. Suto, H.A., D.T.U., R.H.D., H. Saito, and S.J.G. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen J. Galli, Department of Pathology, L-235, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Dr, Stanford, CA 94305-5324; e-mail:sgalli@stanford.edu or Susumu Nakae, snakae@nch.go.jp.

![Figure 2. Effect of anti–TIM-1, anti–TIM-3, or rmTIM-4 on mast-cell function. C57BL/6J BMCMCs were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE (H1-ϵ-26) at 37°C overnight and then washed. Naive or IgE-sensitized C57BL/6J BMCMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of Ag (DNP-HSA, 20 ng/mL) together with (A) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 1 hour for β-hexosaminidase (β-Hex) release assay (P +I = PMA [0.1 μg/mL] + Ionomycin [1.0 μg/mL]); (B) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production; (C) 0 to 100 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (D) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 80 μg/mL anti–TIM-4 pAb or control IgG (goat IgG) at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE-sensitized cells ± Ag; (E) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 0 to 40 μg/mL rmTIM-1 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (F) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 days in the absence of IL-3 for apoptosis (the same data for culture with IL-3, rat IgG and goat IgG, or without any reagents [medium] are shown in the top and bottom panels for each group of BMCMCs); (G) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days for IL-3 production; (H,I) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days in the absence of IL-3 for Bcl-2 expression (the FACS data shown are representative of those obtained in 3 experiments using 3 different batches of BMCMCs). Top numbers indicate MFI for anti–Bcl-2 mAb staining; bottom numbers, MFI for control IgG staining. “IL-3” indicates results for BMCMCs maintained in IL-3–containing WEHI-3 cell-conditioned medium. (A-G, I) *P < .05 versus corresponding values for cells cultured with control IgG (B,D,F,G) or with no rmTIM-4 or rmTIM-1 (0 μg/mL) (C,E). Data shown in panels A to G and I are the average ± SEM (n = 3) of duplicate values for each condition obtained from an experiment done using 3 different batches of BMCMCs; such experiments were done 2 to 4 times each, and each of these gave similar results.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/110/7/10.1182_blood-2006-11-058800/2/m_zh80210708280002.jpeg?Expires=1768241774&Signature=o2Xdb6V~y8H6YbuylSaiMVUm38wp7XifeVrKGKLKs2uchDJqnwWaucm-d4SQ7MS-9AZJ1FPuhlZFWNRcD8leOuQ06xnVYgu0OvazsSA-zQUpHo8iRTV7nmqRssu~y5H3WYg3VrnQNiwMiGJdm9xBbv75b~ZBWTTbtNIk~9ksz09dY3WY88LZoiH6vt-Mwd9zTvWqXuL2PyvnqSksMTXFPAJ8BDWA6i-dIq~vYAlqZlwx~fNPSSMKN1vzCVTqv5zxLRIta64nsFNqBKKgbploFnv4Ac-UNnMbmVXHgMY6W6BGQsedYXWdvSb6TDWNvu2EZBe-3CmN9thzqLbOepdUCQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. Effect of anti–TIM-1, anti–TIM-3, or rmTIM-4 on mast-cell function. C57BL/6J BMCMCs were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE (H1-ϵ-26) at 37°C overnight and then washed. Naive or IgE-sensitized C57BL/6J BMCMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of Ag (DNP-HSA, 20 ng/mL) together with (A) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 1 hour for β-hexosaminidase (β-Hex) release assay (P +I = PMA [0.1 μg/mL] + Ionomycin [1.0 μg/mL]); (B) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production; (C) 0 to 100 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (D) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 80 μg/mL anti–TIM-4 pAb or control IgG (goat IgG) at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE-sensitized cells ± Ag; (E) 40 μg/mL rmTIM-4 and 0 to 40 μg/mL rmTIM-1 at 37°C for 6 hours for cytokine production in IgE/Ag-stimulated cells; (F) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG or 20 μg/mL rmTIM-4 at 37°C for 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 days in the absence of IL-3 for apoptosis (the same data for culture with IL-3, rat IgG and goat IgG, or without any reagents [medium] are shown in the top and bottom panels for each group of BMCMCs); (G) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days for IL-3 production; (H,I) 20 μg/mL anti-TIM Abs or control IgG at 37°C for 2 days in the absence of IL-3 for Bcl-2 expression (the FACS data shown are representative of those obtained in 3 experiments using 3 different batches of BMCMCs). Top numbers indicate MFI for anti–Bcl-2 mAb staining; bottom numbers, MFI for control IgG staining. “IL-3” indicates results for BMCMCs maintained in IL-3–containing WEHI-3 cell-conditioned medium. (A-G, I) *P < .05 versus corresponding values for cells cultured with control IgG (B,D,F,G) or with no rmTIM-4 or rmTIM-1 (0 μg/mL) (C,E). Data shown in panels A to G and I are the average ± SEM (n = 3) of duplicate values for each condition obtained from an experiment done using 3 different batches of BMCMCs; such experiments were done 2 to 4 times each, and each of these gave similar results.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/110/7/10.1182_blood-2006-11-058800/2/m_zh80210708280002.jpeg?Expires=1768594312&Signature=sIbG6Upx-7RdqCs34nT~fLUWQ3hDsSUQzku2bn-ZM6SEMLwOFTcAZ9Wqbzlnfnks5GnifoFJq7ks-nXPaHxCnJPbO2NHM5JpAHfYP0NBXCkCBWxEbbHD6FtOeiGpjzuOl4cvM9YBXKIMfbVDnEmQbufVlon~-W9FpBq~cOoSOsUvjnUywCYvRHMk93jhG-jRtoq8S6A1QJGtqK6~bz-NMJQaXO4z~kBB58u7JOH7y4k75Jgr7CgR2iKB7w1q2oTCEUxzN9kdbubYVKAX1kzfi67O9GB-Uz22OEMWNxc9NA8uSsXhwgJayoe9eVFFmbjDIAXt6vcWLmOXDo4Xhtv2BQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)