Abstract

Cysteinyl leukotrienes (cys-LTs) induce inflammation through 2 G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), CysLT1 and CysLT2, which are coexpressed by most myeloid cells. Cys-LTs induce proliferation of mast cells (MCs), transactivate c-Kit, and phosphorylate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Although MCs express CysLT2, their responses to cys-LTs are blocked by antagonists of CysLT1. We demonstrate that CysLT2 interacts with CysLT1, and that knockdown of CysLT2 increases CysLT1 surface expression and CysLT1-dependent proliferation of cord blood–derived human MCs (hMCs). Cys-LT–mediated responses were absent in MCs from mice lacking CysLT1 receptors, but enhanced by the absence of CysLT2 receptors. CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors colocalized to the plasma membranes and nuclei of a human MC line, LAD2. Antibody-based fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy confirmed complexes containing both receptors based on fluorescence energy transfer. Negative regulation of CysLT1-induced mitogenic signaling responses of MCs by CysLT2 demonstrates physiologically relevant functions for GPCR heterodimers on primary cells central to inflammation.

Introduction

The cysteinyl leukotrienes (cys-LTs) LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 are inflammatory mediators derived from arachidonic acid and generated in vivo by mast cells (MCs), eosinophils, basophils, and alveolar macrophages. Cys-LTs are powerful contractile agonists for vascular and bronchial smooth muscle,1 reflected by bronchoconstriction in human subjects,2 and by rapid vascular leak in passive cutaneous anaphylaxis and experimental peritonitis in mice.3 The known functions of cys-LTs are mediated by 2 G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), termed CysLT1 and CysLT2.4,5 A recently deorphanized GPCR (GPR17) is dual selective for cys-LTs and uracil nucleotides and dominantly expressed in the brain.6 Although the CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors induce similar signaling events (calcium flux and inositol phosphate accumulation) when heterologously expressed in isolation by Xenopus oocytes,4,5 they are not functionally redundant. Each mediates distinct responses in vivo,7 and each has a unique pattern of cellular and tissue distribution.4,5 Several leukocyte subsets in peripheral blood and inflammatory lesions express both CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors.8 It is thus possible that these receptors interact to regulate cys-LT–mediated responses in inflammation, although the functional significance of coexpression of these receptors by cells of the immune system remains unknown

MCs are tissue-dwelling effector cells that are central to asthma and allergic diseases in humans.9 MCs also initiate vascular leak and inflammation in mouse models of allergy, innate immunity, and autoimmune diseases (reviewed in Rottem and Mekori10 ). MC hyperplasia is a common feature of allergic mucosal inflammation. MCs express both CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors, and cys-LTs potently induce calcium flux11 and phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase-1 (MEK-1) and its downstream effector, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK),12,13 in human MCs (hMCs) cultured from cord blood. These signaling events result in MC proliferation,14 reflecting transactivation of c-Kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that binds stem cell factor (SCF) and is essential for MC development in vivo.15 Mice lacking leukotriene C4 synthase (LTC4S), the terminal enzyme needed for cys-LT synthesis, show markedly blunted mucosal MC hyperplasia in the lungs when sensitized and challenged with allergen, revealing a physiologic function of cys-LTs for MC development in vivo.16 Most cys-LT–mediated responses in vitro can be blocked by treatment of the MCs with a CysLT1 receptor–selective antagonist, MK571. The lack of selective CysLT2 receptor antagonists has precluded a comprehensive analysis of the contributions from this receptor to the integrated functions of cys-LTs on MCs and other primary cell types to date.

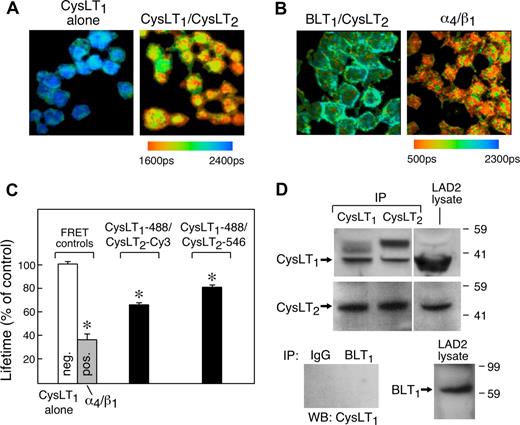

In the current study, we report that LTD4-mediated proliferation is abrogated in hMCs subjected to short-hairpin RNA (shRNA)–mediated knockdown of CysLT1 receptor expression, and is also absent in mouse bone marrow–derived MCs (mBMMCs) from Cysltr1−/− mice. In striking contrast, LTD4-induced proliferation of MCs is enhanced by knockdown or knockout of CysLT2 receptors. Although the absence of CysLT2 does not change the total cellular level of CysLT1 protein, it increases CysLT1 expression at the cell surface and enhances LTD4-induced ERK phosphorylation. CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors colocalize at the plasma membrane, nucleus, and nuclear envelope of MCs, and form heteromeric complexes as determined by Ab-based fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) to measure fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET)17 in intact LAD2 cells (a human MC line).18 CysLT2 receptors limit the strength of signaling through CysLT1 receptors, at least partly by controlling membrane expression, and thus can function as negative regulators of cys-LT–induced MC responses.

Materials and methods

Reagents

LTD4 and MK571 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Polyclonal antihuman Abs against the LTB4 receptor BLT1, CysLT1 (against C-terminal amino acids 318–337 [YVPRKKASLPEKGEEICKV]), and CysLT2 (against N-terminal amino acids 1–18 [MERKFMSLQPSISVSEME], and against C-terminal amino acids 330–346 [TKCVFPVSVWLRKETRV]), and a rabbit IgG control were all purchased from Cayman Chemical. A polyclonal antipeptide Ab (RB34, against the conserved sequence DEKNNTKCFEPPQNN of EC3 of both mouse and human CysLT1 receptors) and the corresponding blocking peptide were custom generated by Orbigen (San Diego, CA). A monoclonal anti-CysLT2 peptide Ab (clone 1B3, IgG2a against the N-terminal amino acid sequence MERKFMSLQPSISVSEME of human CysLT2 receptor) and blocking peptide were provided by Nita Frank (Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA). FITC-conjugated donkey antimouse and antirabbit Abs, antihuman polyclonal anti-α4 integrin, and monoclonal anti-β1 and anti-CXCR2 Abs were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG and Cy3-conjugated donkey anti–mouse IgG were purchased from Invitrogen (Frederick, MD). Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 546 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and Cy3 (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) were used for direct labeling according to the manufacturers' protocols. Recombinant human and mouse cytokines were all purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Derivation of MCs

The use of cord blood for this study is covered under a protocol for the use of discarded human materials approved by the Partners Healthcare Human Research Committee. hMCs were derived from cord blood mononuclear cells as described.19 mBMMCs were derived from bone marrow14 and studied at 4 to 6 weeks when virtually all stained with toluidine blue. LAD2 cells (provided by Dr Arnold Kirshenbaum, NIH, NIAID, Bethesda, MD) were maintained in SpemPro34 medium containing SCF (100 ng/mL).18 Mitogenic assays were performed on triplicate cell samples in the presence of SCF (10 ng/mL) with or without LTD4 (500 nM). This dose was chosen based on its ability to saturate both receptors,4,5 and provide maximal CysLT1-dependent proliferation and ERK activation.14

Mice

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis immunoblotting and Kit transactivation

Cytokine-starved hMCs were stimulated for 5 minutes with various doses of LTD4, SCF (100 ng/mL), or medium, lysed, and processed for Western blotting as described previously.14 Blots were probed with anti–Active ERK, total ERK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), and phosphorylated mouse c-Kit (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA). The signals were detected by chemiluminescence and the densities of the bands were quantitated by densitometry using a Chemi Imager 4400 (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Phospho-ERK signals were corrected as a ratio of the corresponding total ERK. The corrected phospho-ERK signals for the unstimulated cells did not differ significantly between genotypes, and thus these values were expressed as 100% of control for that genotype in each experiment. The dosing range of LTD4 (10-1000 nM) was chosen so as to be at or higher than the threshold for saturation of both receptors.

Immunoprecipitations

Abs were coupled to columns of a ProFound immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Lysates were generated from primary hMCs and LAD2 cells, and 2.5 × 107 cell equivalents were used for each sample. Immunoblotting of the eluted proteins was performed using the indicated Abs.

Flow cytometry

CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptor proteins were detected in permeabilized cells using anti–C-terminal Abs as described elsewhere.21 Specificity was confirmed by demonstrating diminished levels of staining in LAD2 cells and hMCs treated with receptor-selective shRNAs. Anti-CysLT1 (RB34, 7 μg/mL) and anti-CysLT2 Abs (1B3, 10 μg/mL) were used to detect the receptors on nonpermeabilized hMCs, LAD2 cells, and (in the case of RB34) mBMMCs. Specificities of the new Abs were confirmed using blocking peptides and, in the case of RB34, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis with CysLT1−/− mBMMCs. Nonspecific rabbit and mouse IgG (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were used as controls. Flow cytometry analyses were performed on a FACSort calibur flow cytometer, and data were analyzed using Cell Quest Pro software (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) as described.11 Data were calculated as net MFI (fluorescence intensity of the anti-CysLT1 staining minus the staining of the IgG control). There were no significant differences in the staining of different mBMMC populations with the IgG control (MFI: 5.4 ± 1.3, 4.6 ± 1.1, and 6.1 ± 0.9 for the WT, CysLT1−/−, and CysLT2−/− mBMMCs, respectively).

Preparation of lentiviral particles and transfection

shRNA constructs were purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). The constructs were designed to include a hairpin of 21 base pair of a sense strand and an antisense strand, and a 6 base-pair loop. The sequences were (reading from 5′ to 3′) as follows: CysLT1: CCGGGCGTGACTTATGTACCCAGAACTCGAGTTCTGGG TACATAAGTCACGCTTTTT; CysLT2: CCGGCCTGCAGGATTATGTCTTATTCTCGAGAATAAGACATAAT-CCTGCAGGTTTTT Each hairpin sequence was cloned in frame with a lentiviral vector (pLKo1; Open Biosystems). Clones were verified by automated sequencing. Infectious viral particles were prepared by cotransfection of 293FT cells with the pLKo1 and a lenitival packaging mix (Virapower; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After titering the viral stocks in Hela cells, the lentivirus particles were concentrated by high-speed centrifugation. LAD2 and hMC suspensions were prepared at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/mL in StemPro 34 medium in a 75-cm flask. Viral stocks were added directly to the medium at a quantity sufficient to achieve a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, based on preliminary experiments in which FACS analysis was used to assess the effect of the transfection on the expression of the target receptors. The cells were incubated overnight with the particles at 37°C. The following day, the medium was replaced and the cells were cultured for an additional 48 hours before performing the functional studies.

Immunostains and confocal imaging

LAD2 cells were fixed in suspension with 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on ice for 10 minutes. The cells were washed once with wash buffer (PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide) and resuspended in blocking buffer (PBS containing 5% horse serum). The cells were immobilized on round 12-mm coverslips by cytocentrifugation and postfixed with methanol at − 20°C for 10 minutes. The slides were washed twice with wash buffer and then blocked with blocking buffer, shaking at room temperature for 30 minutes. The cells were stained with primary Abs that were labeled directly with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 546 (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's specifications. Alternately, cells were stained with unlabeled primary Abs, followed by donkey anti–rabbit-FITC at 1:100, and donkey anti–mouse-Cy3 at 1:1000. Five percent donkey serum (Jackson Immunoresearch, Bar Harbor, ME) was added to the blocking buffer when indirect staining was used. The cells were counterstained with DRAQ5 nuclear stain (1:1000; Biostatus, Leicestershire, United Kingdom). Anti-CysLT1 C-terminal Ab (1:100), RB34 (1:100), and monoclonal or polyclonal anti-CysLT2 N-terminal Abs (1:50) were used at the indicated dilutions, and species- and isotype-matched control IgGs were used at the same concentrations. Subcellular localization of the receptors was assessed using a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope with a Nikon C1 plus laser scanning confocal system (Melville, NY). Images were acquired through a 30-μm pinhole with a Nikon 60× Oil CFI Plan Apochromat objective and analyzed with Nikon EZ-C for Nikon C1 Confocal Software, Gold Version 3.40 build 691. The resolution was set for the highest possible given the objective and lasers according to the Nikon software (in most cases, 71 nm/pixel ± 1 nm). A 1.68 usec/pixel dwell time was used to capture a single z section. The 2-dimensional images were captured as 12-bit color images, which were then saved as 8-bit images by adjusting the histogram to remove any superfluous gray values using Photoshop CS1 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

FLIM

The cells were fixed and stained for the FLIM analysis as described for confocal imaging. Cells were double stained with 1:100 dilutions of polyclonal Abs against CysLT1 (RB34), BLT1, or α4 integrin, in various combinations with monoclonal (1B3) or polyclonal Abs to CysLT2, monoclonals against CXCR2 or β1 integrin, or with isotype controls. The cells were counterstained with secondary antirabbit–Alexa Fluor 488 (donor) and antimouse-Cy3 (acceptor) conjugates. In some experiments, anti-CysLT1 Ab RB34 and the polyclonal anti–N-terminal CysLT2 peptide Ab were labeled directly with Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 546 (or Cy3) to eliminate any potential FRET signal caused by interactions between secondary Abs and reorientation of fluorophores. Primary Abs were omitted in some samples as specificity controls. Cy3 and Alexa Fluor 546 were chosen as acceptor fluorophores because their excitation spectra overlap with the emission spectrum of Alexa Fluor 488. IgG alone was directly labeled as a control. Some cell samples were stimulated with 100 nM LTD4 for various intervals before fixation and staining. To confirm double labeling and colocalization of receptors, confocal images were taken using 488-nm and 543-nm single-photon excitation to excite Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 (or Alexa Fluor 546), respectively (Zeiss LSM510/NLO; Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany). Emissions were separated in multitrack mode. FLIM was performed using a microscope (Zeiss LSM510/NLO) and a femtosecond-pulsed Ti:Sapphire laser (Chameleon, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA), with a multichannel plate photon counting detector (R3809; Hamamatsu, Okayama City, Japan). A time-correlated single-photon counting board and software (SPC830; Becker and Hickl, Berlin, Germany) was used for acquisition, and images were analyzed using SPCImage software (version 2.6.1.2711; Becker and Hickl) with monoexponential and biexponential lifetime curve fits.22 A minimum of 6 fields was analyzed for each condition in each experiment, with each field containing a minimum of 4 cells and a maximum of 30 cells. Lifetimes were analyzed as whole-cell measurements. FRET is indicated by shortening of the donor fluorophore's lifetime and will occur if the 2 fluorophores are within 10 nm of each other. The non-FRETing fluorescence lifetime of the donor fluorophore (Alexa Fluor 488) was measured in the absence of the acceptor fluorophores (negative control) in each experiment. Results using Cy3 as an acceptor were similar to those using Alexa Fluor 546, and direct and indirect labeling methods revealed similar degrees of FRET.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean plus or minus SEM from at least 3 experiments except where otherwise indicated. Differences between treatment groups were determined with the Student t test. For the FRET studies, differences in lifetimes were assessed by ANOVA, with a Bonferroni analysis to correct for multiple comparisons.

Results

Coexpression and colocalization of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors and validation of Abs

We had previously reported that human MCs express both CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptor proteins.11,21 A recent study of human bronchial fibroblasts23 questioned the specificity of the anti–C-terminal Ab against human CysLT1 that we had used for our previous studies. We therefore sought to validate this Ab reagent, and to generate additional reagents for the identification of both receptors. FACS using anti–C-terminal peptide Abs on permeabilized LAD2 cells and hMCs detected both CysLT1 and CysLT2 proteins (Figure 1A). The signals for each receptor were decreased in the cells treated with the corresponding shRNA (Figure 2A). The receptors were also detected by FACS on nonpermeabilized LAD2 cells (Figure 1B) and hMCs (not shown) using RB34, a polyclonal anti-CysLT1 extracellular domain 3 Ab, and 1B3, a monoclonal anti–N-terminal CysLT2 Ab. The signals elicited by each Ab were abrogated by prior treatment of the cells with corresponding blocking peptides, without “cross-blocking” of the nontarget receptors (Figure 1B). The RB34 Ab also detected a strong signal on the surface of WT mBMMCs, but not on mBMMCs from Cysltr1−/− mice (Figure 1C). Confocal imaging of LAD2 cells using the polyclonal anti–C-terminal Abs (Figure 1D) and hMCs (not shown) confirmed that the 2 receptors colocalized at the plasma membrane, the nuclear envelope, and discreet nuclear inclusions (Figure 1D). Similar results were obtained regardless of the combinations of Abs used. Strong membrane and nuclear localization of CysLT1 was also detected in WT and Cyslt2r−/− mBMMCs (not shown).

Coexpression and colocalization of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors by human MCs. Cytofluorographic analyses (A,B) showing expression of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptor proteins by cord blood–derived hMCs and LAD2 cells. Cells were permeabilized for staining with the indicated anti–C-terminal Abs (A) or stained without permeabilization (B) with a polyclonal Ab against the third extracellular domain of CysLT1 (RB34) or with a monoclonal anti-CysLT2 (1B3) against the N-terminal 18 amino acids. The indicated blocking peptides were used to demonstrate specificity. (C) mBMMCs from the indicated genotypes were stained with RB34 with or without the corresponding blocking peptide. Shaded tracings in panels A to C are the isotype controls. Results in each panel are representative of 3 to 5 experiments for each. (D) Confocal images of LAD2 cells stained with directly labeled RB34 (Alexa Fluor 488) and anti–C-terminal CysLT2 Abs. Note staining of plasma membrane (blue arrows), nuclear envelope (white arrows), and nuclear inclusions (black arrows) and colocalization in each location. Results were similar regardless of which combinations of Abs were used. Results are from 1 experiment representative of 3 performed. Results with indirectly labeled Abs were similar (n = 2, results not shown). See “Immunostains and confocal imaging” for complete image acquisition information.

Coexpression and colocalization of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors by human MCs. Cytofluorographic analyses (A,B) showing expression of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptor proteins by cord blood–derived hMCs and LAD2 cells. Cells were permeabilized for staining with the indicated anti–C-terminal Abs (A) or stained without permeabilization (B) with a polyclonal Ab against the third extracellular domain of CysLT1 (RB34) or with a monoclonal anti-CysLT2 (1B3) against the N-terminal 18 amino acids. The indicated blocking peptides were used to demonstrate specificity. (C) mBMMCs from the indicated genotypes were stained with RB34 with or without the corresponding blocking peptide. Shaded tracings in panels A to C are the isotype controls. Results in each panel are representative of 3 to 5 experiments for each. (D) Confocal images of LAD2 cells stained with directly labeled RB34 (Alexa Fluor 488) and anti–C-terminal CysLT2 Abs. Note staining of plasma membrane (blue arrows), nuclear envelope (white arrows), and nuclear inclusions (black arrows) and colocalization in each location. Results were similar regardless of which combinations of Abs were used. Results are from 1 experiment representative of 3 performed. Results with indirectly labeled Abs were similar (n = 2, results not shown). See “Immunostains and confocal imaging” for complete image acquisition information.

Effect of CysLT2 receptors on CysLT1 receptor–dependent proliferation. (A) LAD2 cells and hMCs were treated for 48 hours with lentivirus encoding the indicated shRNA or with empty vector with MOIs of 10 for each. FACS analysis of permeabilized cells showing effect of shRNA treatment on-target and off-target receptor expression. The net MFI for each protein is displayed for the experiment depicted. (B) Effect of shRNA treatments on surface expression of the indicated receptors detected on nonpermeabilized LAD2 cells stained with RB34 and 1B3 Abs. Results in panels A and B are representative of 3 experiments each. (C) FACS of mBMMCs from indicated genotypes using RB34 without or with permeabilization. The curves for the isotype control of the 2 genotypes (shaded) are superimposable. The net mean MFI for CysLT1 surface expression for 5 experiments is shown (right). (D) Proliferation of hMCs in response to SCF with or without LTD4 (500 nM) and effect of CysLT1 or CysLT2 receptor knockdowns. Results are the mean (± SEM) from 3 separate experiments using cells from different donors. (E) Proliferation of mBMMCs from C57BL/6 mice of the indicated genotypes in response to SCF with LTD4. Date were normalized in each experiment to the response of each genotype to SCF only, which is set at 100%. Note the complete blockade of the LTD4-mediated increment by MK571 (1 μM). Results are the mean (± SEM) from 4 separate experiments using cells from different animals.

Effect of CysLT2 receptors on CysLT1 receptor–dependent proliferation. (A) LAD2 cells and hMCs were treated for 48 hours with lentivirus encoding the indicated shRNA or with empty vector with MOIs of 10 for each. FACS analysis of permeabilized cells showing effect of shRNA treatment on-target and off-target receptor expression. The net MFI for each protein is displayed for the experiment depicted. (B) Effect of shRNA treatments on surface expression of the indicated receptors detected on nonpermeabilized LAD2 cells stained with RB34 and 1B3 Abs. Results in panels A and B are representative of 3 experiments each. (C) FACS of mBMMCs from indicated genotypes using RB34 without or with permeabilization. The curves for the isotype control of the 2 genotypes (shaded) are superimposable. The net mean MFI for CysLT1 surface expression for 5 experiments is shown (right). (D) Proliferation of hMCs in response to SCF with or without LTD4 (500 nM) and effect of CysLT1 or CysLT2 receptor knockdowns. Results are the mean (± SEM) from 3 separate experiments using cells from different donors. (E) Proliferation of mBMMCs from C57BL/6 mice of the indicated genotypes in response to SCF with LTD4. Date were normalized in each experiment to the response of each genotype to SCF only, which is set at 100%. Note the complete blockade of the LTD4-mediated increment by MK571 (1 μM). Results are the mean (± SEM) from 4 separate experiments using cells from different animals.

Effect of CysLT2 receptor deficiency on LTD4-mediated proliferation of MCs

To determine the potential functional relevance of CysLT1-CysLT2 interactions for MC responses to cys-LTs, we treated hMCs and LAD2 cells with shRNA constructs designed to suppress the expression of each receptor packaged into recombinant lentivirus.24 FACS of permeabilized cells revealed that the knockdowns suppressed the expression of the target receptor proteins. In LAD2 cells (but not in hMCs), CysLT1 knockdown increased CysLT2 expression levels by approximately 2-fold relative to mock-transfected controls (n = 3, as shown for one experiment, Figure 2A). FACS of nonpermeabilized cells revealed that knockdown of CysLT2 modestly but consistently increased the level of surface CysLT1 (∼ 2-fold increase), but CysLT1 knockdown did not change surface levels of CysLT2 (n = 3, as shown for one experiment, Figure 2B). A similar trend was observed in mBMMCs from Cyslt2r−/− mice (Figure 2C). Both basal and LTD4-stimulated proliferation of the LAD2 cells was suppressed even by the control transfection, and thus these cells were not used for the mitogenic analysis. However, hMCs transfected with empty vector showed the same 2-fold LTD4-mediated increase in the rate of thymidine incorporation that was observed in the nontransfected cells (not shown). CysLT1 receptor knockdown abrogated this increase, while CysLT2 receptor knockdown significantly amplified the increase (Figure 2D). In mBMMCs, the LTD4-mediated increment in proliferation was absent in Cysltr1−/− cells, but amplified in Cysltr2−/− cells (Figure 2E). The LTD4-induced increment in proliferation observed in the Cysltr2−/− mBMMCs was abrogated by treatment of the cells with MK571. Basal SCF-dependent proliferation of hMCs was unaltered by the knockdowns, and did not differ among the mBMMCs from the 3 genotypes (mean ± SEM: 14 968 ± 3913, 14 223 ± 6817, and 13 270 ± 6550 cpm for wild-type, Cysltr1−/−, and Cysltr2−/− cells, respectively; n = 4).

Effect of CysLT2 deficiency on CysLT1-dependent ERK phosphorylation, c-Kit transactivation, and CysLT1 surface expression.

Stimulation of wild-type mBMMCs with LTD4 alone for 5 minutes caused ERK phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner, which required the presence of CysLT1 receptors. The absence of CysLT2 receptors enhanced LTD4-mediated ERK phosphorylation at every concentration (Figure 3A,B). Both WT and Cysltr2−/− mBMMCs showed robust and equal c-Kit phosphorylation in response to LTD4 at 100 and 1000 nM; this was not observed for Cysltr1−/− mBMMCs. The cells of all 3 genotypes responded to SCF (Figure 3A).

Effect of receptor deletions on LTD4-induced ERK phosphorylation and c-Kit transactivation. (A) Dose-dependent LTD4-induced c-Kit and ERK phosphorylation in mBMMCs from the indicated genotypes. Results are from a single experiment repeated 4 times with cells from different animals. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes. (B) Quantitative densitometry of phospho-ERK signals corrected for the baseline for each genotype from 5 experiments.

Effect of receptor deletions on LTD4-induced ERK phosphorylation and c-Kit transactivation. (A) Dose-dependent LTD4-induced c-Kit and ERK phosphorylation in mBMMCs from the indicated genotypes. Results are from a single experiment repeated 4 times with cells from different animals. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes. (B) Quantitative densitometry of phospho-ERK signals corrected for the baseline for each genotype from 5 experiments.

Interactions between CysLT1 and CysLT2

Ab-based multiphoton FLIM17,22 was used to assay for physical interactions between CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors in intact MCs based on FRET. We separately tested for FRET using different combinations of each polyclonal Ab against the CysLT1 receptor with either the polyclonal or monoclonal Abs against the CysLT2 receptor to ensure consistency of the results, and used both direct and indirect labeling of these Abs with the fluorophores to control for potential artefactual interactions between secondary Abs. FLIM of the cells stained with anti–CysLT1–Alexa Fluor 488 alone (the negative control for FRET) gave an average lifetime of 1.9 ns (Figure 4C, as shown for one field, Figure 4A). LAD2 cells stained with anti-CysLT1 Ab RB34 in combination with either polyclonal or monoclonal anti-CysLT2 N-terminal Abs showed significant FRET (n = 4, as shown for one experiment using polyclonal anti-CysLT2, Figure 4A). Similar degrees of FRET were observed using either direct or indirect labeling methods, and using either Cy3 or Alexa Fluor 488 as acceptor fluorophores (Figure 4C). Areas of FRET were detected in the nucleus as well as in proximity to the plasma membrane. In contrast, no FRET was detected between BLT1 and CysLT2 or CXCR2 and CysLT1 receptors used as specificity controls, whereas the α4 and β1 integrins (used as a positive control) showed strong interaction (n = 3, as shown for one experiment, Figure 4B). Immunoprecipitates generated from hMCs (not shown) and LAD2 cells with either anti-CysLT1 or anti-CysLT2 polyclonal Abs demonstrated coprecipitation of the 2 receptors by Western blot (Figure 4D). Abs against the BLT1 receptor for LTB4 or IgG alone failed to coprecipitate cys-LT receptors (Figure 4D). LAD2 cells (Figure 4D) and hMCs (not shown) expressed BLT1 protein.

Heterodimerization of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors. FLIM images (A,B) showing interactions between the indicated receptors on LAD2 cells stained with directly labeled Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CysLT1 EC3 Abs (RB34) without or with Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated anti-CysLT2 N-terminal polyclonal Abs (A). Pseudocolor images are from 1 experiment representative of 4 performed and are similar to experiments performed with anti-CysLT2 N-terminal monoclonal directly or indirectly labeled with Cy3 (not shown). (B) Noninteracting (BLT1/CysLT2) and interacting (α4/β1) controls for FRET. Combinations of Abs against BLT1 (Alexa Fluor 488) plus CysLT2 (Cy3) (B left), or α4 (Alexa Fluor 488) and β1 (Cy3) integrins (B right). Data are from 1 experiment representative of 3. Orange color (see scale) indicates the areas of strongest FRET. See “FLIM” for complete image acquisition information. (C) Biexponential analysis of FRET comparing cells stained with the directly fluorophore-conjugated Abs (Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated RB34, plus Cy3- or Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated rabbit antihuman CysLT2 N-terminal Ab). Similar results were obtained with indirect labeling using RB34 and monoclonal antihuman CysLT2 Abs. Results are the mean of 3 to 4 experiments using each Ab combination. *P < .001 relative to the negative control (CysLT1-Alexa-488 alone). (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of CysLT1 and CysLT2 from lysates of hMCs. CysLT1 was precipitated and detected with rabbit antihuman EC3 Ab (RB34), whereas CysLT2 was precipitated with rabbit anti–N-terminal CysLT2 Ab and detected with mouse anti-CysLT2 monoclonal Ab 1B3. Note the presence of the likely rabbit IgG heavy chain (top). Protein equivalents of 2.5 × 107 cells were used to generate the precipitates, whereas 1 × 106 cell equivalents of whole-cell lysates were used as controls. Data are from a single experiment representative of 4 performed with cells from different donors. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes.

Heterodimerization of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors. FLIM images (A,B) showing interactions between the indicated receptors on LAD2 cells stained with directly labeled Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CysLT1 EC3 Abs (RB34) without or with Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated anti-CysLT2 N-terminal polyclonal Abs (A). Pseudocolor images are from 1 experiment representative of 4 performed and are similar to experiments performed with anti-CysLT2 N-terminal monoclonal directly or indirectly labeled with Cy3 (not shown). (B) Noninteracting (BLT1/CysLT2) and interacting (α4/β1) controls for FRET. Combinations of Abs against BLT1 (Alexa Fluor 488) plus CysLT2 (Cy3) (B left), or α4 (Alexa Fluor 488) and β1 (Cy3) integrins (B right). Data are from 1 experiment representative of 3. Orange color (see scale) indicates the areas of strongest FRET. See “FLIM” for complete image acquisition information. (C) Biexponential analysis of FRET comparing cells stained with the directly fluorophore-conjugated Abs (Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated RB34, plus Cy3- or Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated rabbit antihuman CysLT2 N-terminal Ab). Similar results were obtained with indirect labeling using RB34 and monoclonal antihuman CysLT2 Abs. Results are the mean of 3 to 4 experiments using each Ab combination. *P < .001 relative to the negative control (CysLT1-Alexa-488 alone). (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of CysLT1 and CysLT2 from lysates of hMCs. CysLT1 was precipitated and detected with rabbit antihuman EC3 Ab (RB34), whereas CysLT2 was precipitated with rabbit anti–N-terminal CysLT2 Ab and detected with mouse anti-CysLT2 monoclonal Ab 1B3. Note the presence of the likely rabbit IgG heavy chain (top). Protein equivalents of 2.5 × 107 cells were used to generate the precipitates, whereas 1 × 106 cell equivalents of whole-cell lysates were used as controls. Data are from a single experiment representative of 4 performed with cells from different donors. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes.

Discussion

The abundance of extracellular cys-LTs in allergic mucosal inflammation reflects production of these mediators by resident MCs and infiltrating eosinophils, basophils, and macrophages. Unlike these other cells, MCs can proliferate in situ, and the lack of antigen-induced MC hyperplasia in the lungs of LTC4S null mice may in part reflect a role for cys-LTs in the control of this process. Like many hematopoietic cells found in inflammatory lesions, MCs express both CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors.21,25 When heterologously expressed by transfection into cell lines, GPCRs can heterodimerize with other GPCRs that recognize the same or similar ligands26,27 ; these heterodimers can profoundly alter signaling responses. This led us to suspect that cys-LT–dependent mitogenic responses of MCs might be regulated by interactions between CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors.

To avoid the potential confounding influences of artifacts induced by overexpressing GPCRs in transfected cells, we used primary hMCs, mBMMCs, and LAD2 cells (a human MC line)18 for studies of receptor interactions. Both receptors were detected by FACS on permeabilized LAD2 cells and hMCs using respective human-specific Abs against the C-termini of each receptor (Figure 1A), as well as without permeabilization using a new polyclonal anti-CysLT1 extracellular domain 3 (EC3) Ab (RB34), and a monoclonal anti–N-terminal CysLT2 Ab (1B3). The binding of each new Ab was abrogated by treatment of the cells with corresponding blocking peptides, without “cross-blocking” of the nontarget receptors (Figure 1B). The RB34 Ab (against a peptide conserved between the EC3 of the mouse and human receptors) also detected a strong signal on the surface of WT mBMMCs, but not on mBMMCs from CysLT1−/− mice (Figure 1C), further confirming the specificity of this reagent.

We next used confocal imaging to determine the subcellular localization of the CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors in LAD2 cells. We stained the cells using various combinations of each anti-CysLT1 Ab along with either 1B3 or a polyclonal anti–N-terminal CysLT2 Ab directed to the same peptide. The cells were stained with primary Abs directly labeled with fluorophores (Alexa Fluor 488 for CysLT1, Alexa Fluor 546 or Cy3 for CysLT2) in some experiments, and in others were indirectly labeled with fluorophore-conjugated secondary Abs. Regardless of the combination of Abs or labeling method used, CysLT1 colocalized with CysLT2 on the plasma membrane, at the nuclear envelope, and within discreet nuclear inclusions (Figure 1D). Nonspecific IgG did not stain the cells. CysLT1 constitutively localizes to the outer nuclear envelope of human colonic carcinoma cells,28 and translocates to this location in LTD4-stimulated primary epithelial cells, where it regulates mitogenic signaling and intranuclear activity of the ERK pathway. The obligate biosynthetic enzyme LTC4S also localizes to the nuclear envelope of MCs and other hematopoietic cells,29 and the presence of 2 cys-LT receptors at the synthetic organelle for LTC4 may permit intracrine functions as proposed in our previous study.14 Moreover, the constitutive colocalization of these receptors to both the nucleus and cell surface of MCs highlights the potential for receptor-receptor interactions to regulate cys-LT–dependent signaling.

Although blockade by selective antagonists such as MK571 infers cellular responses mediated by CysLT1, MK571 can also have off-target effects, such as interference with sphingosine-1-phosphate transport30 and blockade of purinergic receptors.31 Moreover, selective antagonists of CysLT2 receptors are not currently available. Thus we used a shRNA “knockdown” approach for each receptor to determine the potential functional relevance of CysLT1-CysLT2 interactions for MC responses to extracellular cys-LTs. FACS of permeabilized cells using anti–C-terminal Abs revealed that the knockdowns suppressed the expression of the target receptor proteins (Figure 2A). While the knockdowns did not change the total cellular expression of the nontarget receptors, CysLT2 knockdown unexpectedly caused a 2-fold increase in surface expression of CysLT1 by LAD2 cells (as shown in Figure 2B). Likewise, the levels of CysLT1 protein surface expression (but not total cellular expression) were significantly higher on mBMMCs from Cyslt2r−/− mice than from wild-type controls (Figure 2C). In both human and mouse MCs, the loss of CysLT1 receptors abrogated the increment in proliferation induced by LTD4 (Figure 2D,E), confirming the requirement for this receptor for the mitogenic response.14 In striking contrast, the loss of CysLT2 receptors significantly enhanced LTD4-dependent proliferation of both cell populations (Figure 2D,E). Thus CysLT2 receptors down-modulate CysLT1 receptor–dependent proliferation in the MCs of both mice and humans, possibly by limiting the number of CysLT1 receptors expressed at the cell surface and thus access of the latter to extracellular ligands. Alternatively, CysLT2 receptors could serve as a physiologic “decoy” and limit access of CysLT1 to its ligands. The availability of Abs that recognize extracellular epitopes should prompt a reanalysis of levels of membrane presentation of the cys-LT receptors, as opposed to their total levels, as a mechanism for control of cys-LT responsiveness.

Exogenous cys-LTs drive proliferation of cord blood–derived hMCs by inducing CysLT1-mediated transactivation of the c-Kit tyrosine kinase and consequent ERK phosphorylation,14 the latter initiating the cascade of signaling and transcriptional events necessary for incremental proliferation. We sought to determine whether CysLT2 receptors participated in this process. Stimulation of wild-type mBMMCs with LTD4 alone for 5 minutes caused both ERK and c-Kit phosphorylation. Both of these responses were absent in Cysltr1−/− mBMMCs, which nevertheless showed normal responses to SCF, the natural c-Kit ligand. The absence of CysLT2 receptors enhanced LTD4-mediated ERK phosphorylation at every concentration tested, even lower than the dose required for c-Kit transactivation (Figure 3A,B), and shifted the dose of LTD4 needed to induce ERK signaling by at least one log relative to the wild-type cells (n = 5, Figure 3B). CysLT2 did not alter the LTD4-mediated phosphorylation of c-Kit. The phospho-ERK signals in each genotype returned to baseline by 30 minutes (not shown). Thus CysLT2 receptor–dependent control of CysLT1 surface expression limits the strength of mitogenic ERK signaling in response to extracellular cys-LTs, and consequently alters the downstream signals responsible for cell-cycle progression. We cannot exclude the possibility that CysLT2 receptor engagement induces activation of an ERK-specific phosphatase.

Pairs of GPCRs cotransfected into cell lines form combinations of homodimers and heterodimers that have very different signaling properties, with heterodimers regulating surface expression of some GPCRs.26 Few studies have shown that these interactions and functions occur in primary cells.32 The colocalization of CysLT1 and CysLT2 (Figure 1D) and the fact that CysLT2 deficiency caused increased membrane expression of CysLT1 (Figure 2) led us to suspect direct interactions between these receptors on MCs. We used Ab-based multiphoton FLIM17,33 to confirm these interactions based on FRET, a quantitative measure of protein-protein interactions. FRET was consistently detected in resting LAD2 cells when they were stained with combinations of directly or indirectly labeled Abs against peptide sequences in extracellular domains (N-terminus of CysLT2, EC3 of CysLT1) (n = 4 experiments, as shown for one, Figure 4A). The 2 receptors could also be coimmunoprecipitated from lysates of unstimulated LAD2 cells using Abs directed against either one (Figure 4D). Collectively, these studies suggest that a fraction of these receptors constitutively exists as heterodimers on MCs. Coprecipitation was demonstrated with various combinations of Abs and did not occur with anti-BLT1, nonspecific IgG (Figure 4D), or beads alone (not shown). We also detected significant FRET when the FLIM assay was performed using Cy3 rather than Alexa Fluor 488 as the acceptor fluorophore (Figure 4C). With all combinations of Abs, FRET was observed at the cell surface and in the nucleus, suggesting that the areas of colocalization (Figure 1D) included heterodimeric pairs. The complete lack of FRET between BLT1 and CysLT2 or CXCR2 and CysLT1 receptors supports the specificity of this interaction, and combined with the FRET observed with directly labeled Abs rules out a spurious association caused by reorientation of fluorophores on the secondary Abs.

This study establishes that CysLT2 receptors interact with CysLT1 receptors and inhibit functional responses of the latter on MCs. We speculate that the presence of CysLT2 receptors on MCs and other cells expressing both receptor subtypes (macrophages, eosinophils, basophils) may attenuate the strength of cys-LT–mediated signaling by limiting the formation of CysLT1 receptor homodimers and/or controlling their surface expression, although additional mechanisms (heterologous desensitization, competition for ligand) may contribute as well. The possibility that CysLT1/CysLT2“counterbalance” regulates cys-LT–dependent functions in immune and inflammatory responses is supported by the observation that the presence of a coding sequence variant of the CysLT2 receptor that exhibits reduced ligand affinity is associated with substantially increased rates of atopy and asthma in human subjects.34 The fact that deletion of either receptor totally abrogates cys-LT–mediated cutaneous edema4 suggests that CysLT1/CysLT2 heterodimers may regulate vascular responses to cys-LTs. Moreover, there may be circumstances where effector responses that are CysLT2-receptor dependent are dampened by CysLT1 receptors, as suggested by the fact that Cysltr1−/− mice show increases in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis relative to wild-type controls,35 whereas Cysltr2−/− mice are protected from this injury.7 Cys-LT–regulated cellular and tissue responses via heterodimers likely vary depending on the cell type in which the receptors are expressed, the relative abundance of each receptor, and the corresponding cell type–specific signaling pathways involved for each.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI-48802, AI-52353, AI-31599, HL-36110, and EB-00768, and by grants from the Charles Dana Foundation and the Vinik Family Fund for Research in Allergic Diseases.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Y.J. performed all of the functional analyses; L.A.B. carried out the FLIM experiments; B.J.B. supervised the FLIM and interpreted the FRET results; Y.K. developed the critical gene-targeted mice; J.A.B. was responsible for the overall conception of the study and composition of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joshua A. Boyce, One Jimmy Fund Way, Smith Bldg Rm 626, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: jboyce@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.