Patients with myelodysplasia (MDS) show a differentiation defect in the multipotent stem-cell compartment. An important factor in stem-cell differentiation is their proper localization within the bone marrow microenvironment, which is regulated by stromal cell–derived factor (SDF-1). We now show that SDF-1–induced migration of CD34+ progenitor cells from MDS patients is severely impaired. In addition, these cells show a reduced capacity to polymerize F-actin in response to SDF-1. We demonstrate a major role for Rac and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and a minor role for the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 signaling pathway in SDF-1–induced migration of normal CD34+ cells. Furthermore, SDF-1–stimulated activation of Rac and the PI3K target protein kinase B is impaired in CD34+ cells from MDS patients. Lentiviral transduction of MDS CD34+ cells with constitutive active Rac1V12 results in a partial restoration of F-actin polymerization in response to SDF-1. In addition, expression of constitutive active Rac increases the motility of MDS CD34+ cells in the absence of SDF-1, although the directional migration of cells toward this chemoattractant is not affected. Taken together, our results show a reduced migration of MDS CD34+ cells toward SDF-1, as a result of impaired activation of the PI3K and Rac pathways and a decreased F-actin polymerization.

Introduction

In patients with the clonal hematologic disorder myelodysplasia (MDS), a general defect in the multipotent progenitor compartment results in a disturbed proliferation and differentiation of the erythroid, megakaryocytic and myeloid lineages. This results in the formation of dysfunctional mature blood cells, including granulocytes and thrombocytes.1 For instance, bactericidal functions in granulocytes from MDS patients are impaired, and migration of these cells toward the chemoattractant interleukin-8 (IL-8) is severely decreased.2,,–5

Recent evidence suggests that the association and interaction of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) with their bone marrow microenvironment is imperative for their proliferation, differentiation, and function.6,–8 One of the major factors involved in retention and adhesion of HPCs to the bone marrow is the chemokine SDF-1.9 HPCs are capable of migration toward SDF-1, which might be necessary for their proper localization at bone marrow microniches.10

Migration is a complex phenomenon that includes polarization of cells toward a chemoattractant, and cytoskeletal reorganizations.11,–13 Actin-rich lamellopodia are formed at the leading edge of the cell, whereas a retracting uropod is present at the trailing edge. The rate of cell migration has been attributed to the capability of a cell to reorganize its cytoskeleton, more specifically, the rate of conversion of monomeric G-actin to filamentous actin (F-actin).14 F-actin polymerization, cell shape changes, and ensuing migration are under tight regulation of a number of signaling molecules. The best described of these are the Rho GTPases Rac, Rho, and Cdc42, which act as molecular switches by cycling between an active guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–bound state and an inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)–bound state. In HPCs it has been established that Rho-GTPases are necessary for migration,15 although the specific involvement of the individual GTPases has not been elucidated. Another important regulator of migration is the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway.16 Activated PI3K produces the second messenger PIP3, which is membrane-bound and localizes at the leading edge of migrating cells.17 In HPCs, inhibition of PI3K activity abrogates migration toward SDF-1.18 In addition, ERK1/2, a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, has been shown to be involved in migration of several cell types.19,–21 However, the role of ERK1/2 in CD34+ progenitor cells has been disputed.22

We have previously found that IL-8-induced activation of Rac, ERK, and the PI3K pathway was impaired in MDS neutrophils, in conjunction with an impaired migration of neutrophils toward this chemoattractant.3 This raised the question whether these signaling defects, resulting in impaired neutrophil responses, are already present in MDS HPCs and maintained throughout differentiation. We now show that the number of CD34+ cells migrating in response to SDF-1 is decreased in MDS patients, as is the F-actin assembly in these cells. We demonstrate the involvement of the Rac and PI3K pathways in SDF-1–induced migration and F-actin polymerization, and show that the activation of these pathways is affected in MDS HPCs.

Methods

Patients and controls

Heparinized human marrow cells were collected from 17 MDS patients with a mean age of 56 years (range, 21-84 years) after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Bone marrow specimens were obtained at diagnosis, and patients had not yet started on treatment. According to the FAB classification,23 the patients were categorized as RA (n = 11) or RARS (n = 6). Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. None of the patients was treated with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Normal bone marrow was obtained from cardiac surgery patients, after informed consent, before the surgery. Median age of donors was 66 years (range, 41-82 years). The protocols were approved by the human subject review board of the University Medical Center Groningen.

Reagents

Stem–cell factor and Flt3 were a kind gift from Amgen (Seattle, WA). Thrombopoietin was a kind gift from Kirin (Tokyo, Japan). Stromal cell– derived factor (SDF-1α) was obtained from Peprotech (London, United Kingdom). Polyclonal antibody against ERK1/2 (K23) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal antibodies against phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) and phosphorylated PKB/Akt (Ser473) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-Rac antibody was from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was purchased from Alexis (Läufelfingen, Switzerland), the MEK inhibitor U0126 was obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) and the Rac inhibitor NSC23766 was from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Oregon Green 514-phalloidin and Alexa Fluor 594-phalloidin were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Isolation of CD34+ cells

Mononuclear cells were separated by density gradient centrifugation on Lymphoprep (FreseniusKabi, Oslo, Norway) and CD34+ cells were positively selected using the MiniMACS CD34 isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), according to manufacturers protocol. Cells were allowed to recover in hematopoietic progenitor growth medium (HPGM; Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) for 1.5 hours before stimulation with SDF-1. Purity was analyzed routinely, and was greater than 92%.

Cell culture, vectors, and transductions

The human myeloblastic cell line HL-60 (product no. CCL-240; ATCC, Manassas, VA) was cultured in RPMI 1640 (Biowhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA) and 10% fetal calf serum (Bodinco, Alkmaar, the Netherlands). The human kidney cell line 293T (CRL-11 268; ATCC) was cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Biowhittaker) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 10% fetal calf serum. Using FuGENE6 (Roche, Almere, the Netherlands), 293T cells were transduced with 3 μg pCMV Δ8.91, 0.7 μg VSV-G, and 3 μg of pRRL-SFFV-GFP Rac1V12, pRRL-SFFV-GFP Rac1N17, or pRRL-SFFV-GFP. PRRL-SFFV-GFP Rac1V12 and pRRL-SFFV-GFP Rac1N17 were constructed by ligating the BsgrI-BglII fragment of MIGR1 Rac1V12 and MIGR1 Rac1N17 into the pRRL-SFFV-GFP plasmid (a kind gift of Prof Dr C. Baum, Department of Experimental Hematology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany), after excision of the BsgrI and BamHI fragment from this lentiviral vector. After 24 hours, medium was changed to HPGM (Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium) and after 12 hours supernatant containing lentiviral particles was harvested and stored at −80°C. HL60 cells or isolated CD34+ cells that were cultured for 12 hours in the presence of 100 ng/mL stem-cell factor, 100 ng/mL Flt3, and 100 ng/mL thrombopoietin were subjected to 2 rounds of transduction with lentiviral particles in the presence of 4 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma). Transduction efficiency of MDS and normal CD34+ cells was 40% or higher. For subsequent F-actin polymerization assays, GFP + cells were gated. GFP-positive HL60 cells were sorted by MoFlow (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) to obtain a 100% pure transduced population.

FACS analysis

Isolated stem cells were stained with CD34-Fitc, CXCR4-Fitc, or isotype control IgG-Fitc (DAKO, Heverlee, Belgium) for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and fluorescence was determined by flow cytometry (FACScalibur, Becton Dickinson Medical Systems, Sharon, MA).

Migration assay

The migration assay was performed using microchamber Transwell systems with 5-μm pores for CD34+ cells or 8-μm pores for HL60 cells (Corning Costar Incorporated, New York, NY). CD34+ cells were resuspended in HPGM with or without inhibitors for 30 minutes. Subsequently, CD34+ cells or transduced HL60 cells were applied to the upper compartment of the chamber. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 in HPGM present in the lower compartment of the chamber. In experiments with signal transduction inhibitors, the inhibitors were present in the upper and lower compartment. Cells were allowed to migrate to the lower compartment for 4 hours at 37°C. The upper well was removed, transmigrated CD34+ cells or HL60 cells were harvested from the lower chamber and counted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), using a fixed number of Flow-Check Fluorospheres (Beckman Coulter, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands). The assay was done in duplicate. Results are expressed as percentage, which represents the ratio between transmigrated cells and the total amount of cells added to the upper well.

F-actin polymerization assay

F-actin polymerization was measured as described by Nijhuis et al.24 In short, CD34+ cells or transduced HL60 cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1. At indicated time points, cells were fixed and permeabilized for 10 minutes at room temperature with ice-cold 3% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, containing 100 μg/mL lysophosphatidylcholine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Polymerized F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL Oregon Green 514-phalloidin or Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin for 30 minutes at room temperature. The intracellular fluorescence was of SDF-1-stimulated cells was determined by flow cytometry and expressed as a percentage of that of unstimulated cells.

Rac activation assay

Activated Rac was precipitated using the CDC42 and Rac interactive binding (CRIB) domain of PAK (aa 56–272) as described previously.25 Briefly, CD34+ cells or transduced HL60 cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time and lysed for 10 minutes in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 200 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors [1 tablet Complete (Roche) per 50 mL buffer]). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and GST-PAKcrib protein precoupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) was added for 30 to 45 minutes at 4°C. Beads were washed 3 times with 1× lysis buffer and boiled in Laemmli sample buffer. The bound proteins were separated by 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA). Activated Rac was detected by probing the membrane with anti-Rac antibodies and rabbit-anti–mouse peroxidase–conjugated antibodies (DAKO) followed by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Western blotting

The amount of ERK, Rac and the phosphorylation of ERK and PKB/Akt were determined by Western blotting. CD34+ cells were preincubated with inhibitors and stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 as indicated in the figures. Stimulation was terminated by placing the cells on ice, immediate centrifugation, and resuspending the cell pellets in 1× Laemmli sample buffer. After boiling for 10 minutes, the proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran; Schleicher & Schuel, Dassel, Germany). Membranes were probed with antibodies against ERK1/2 (K23), phosphorylated ERK1/2, and phosphorylated PKB/Akt (Ser473) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. Quantification of phosphorylation levels was performed by densitometry of the films, using ImageMaster1D Elite (Pharmacia).

Statistical analysis

For transmigration assays, CXCR4 expression, and F-actin polymerization measurements, differences in experimental values between healthy controls and MDS patients were calculated using the Wilcoxon nonparametric test for paired samples. The Student t test for paired samples was used to compare samples treated with or without signal transduction inhibitors or cells that were transduced with pRRL-390 Rac1V12 or pRRL-390 Rac1N17 compared with empty vector. For comparison of phospho-PKB or phospho-ERK1/2 levels in MDS patients and healthy donors, densitometry values of phospho-PKB or phospho-ERK1/2 protein were corrected for the amount of ERK protein present in the samples, and differences between the normalized values were calculated using the Student t test for paired samples. Likewise, for comparison of Rac activation in MDS patients and healthy donors, densitometry values of Rac-GTP were corrected for the amount of Rac protein present in the samples, and differences between the normalized values were calculated using the Wilcoxon nonparametric test for paired samples. Data were expressed as mean plus or minus standard error of the mean. P values less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

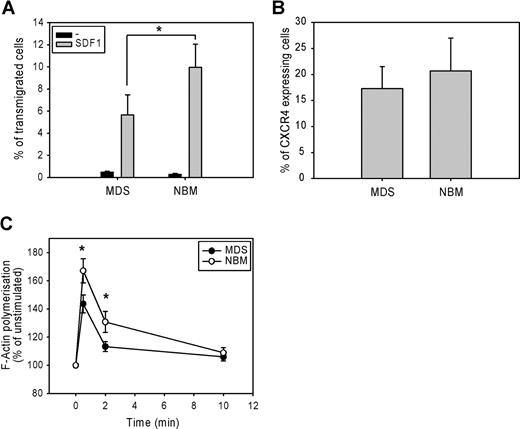

Migration of CD34+ cells is impaired in MDS patients

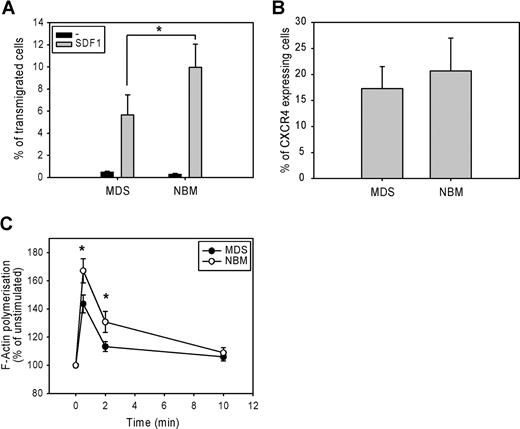

The migration of CD34+ cells from 7 low-risk MDS patients and 7 normal bone marrow samples toward the chemokine SDF-1 was measured in a microchamber chemotaxis assay. Figure 1 A shows that SDF-1-induced migration was significantly lower in MDS CD34+ cells compared with normal CD34+ cells. (5.7 ± 2% vs 10 ± 2%, P = .02). This defect could not be attributed to a lower SDF-1–receptor expression, as the number of CXCR4-expressing cells did not differ between MDS CD34+ cells and normal CD34 + cells (17.3 ± 4% vs 20.7 ± 6%, n = 9, P = .11; Figure 1B). These results suggest that a defect downstream of SDF-1–CXCR4 receptor binding might be responsible for the impaired migration of MDS CD34+ precursor cells.

Impaired migration and F-actin polymerization in CD34+ cells from MDS patients. (A) CD34+ cells from healthy donors (normal bone marrow; NBM) and MDS patients were applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 5 μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 in HPGM present in the lower compartment of the chamber. Cells were allowed to migrate for 4 hours at 37°C after which the transmigrated CD34+ cells were harvested from the lower chamber and counted by FACS analysis. The assay was done in duplicate, and results are expressed as the ratio between transmigrated CD34+ cells and the total amount of CD34+ cells added to the upper well. The means of 7 MDS patients and 7 healthy donors (NBM) are shown. (B) Isolated CD34+ cells were stained with CXCR4-Fitc, or isotype control IgG-Fitc for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and the percentage of CXCR4-Fitc positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. The means of 9 MDS patients and 9 healthy donors are shown. (C) Isolated CD34+ cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL OregonGreen 514-Phalloidin. The fluorescence intensity of SDF-1-stimulated cells was determined by FACS analysis and presented as a percentage of that of unstimulated cells. The means of 8 MDS patients and 8 healthy controls (NBM) are shown.

Impaired migration and F-actin polymerization in CD34+ cells from MDS patients. (A) CD34+ cells from healthy donors (normal bone marrow; NBM) and MDS patients were applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 5 μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 in HPGM present in the lower compartment of the chamber. Cells were allowed to migrate for 4 hours at 37°C after which the transmigrated CD34+ cells were harvested from the lower chamber and counted by FACS analysis. The assay was done in duplicate, and results are expressed as the ratio between transmigrated CD34+ cells and the total amount of CD34+ cells added to the upper well. The means of 7 MDS patients and 7 healthy donors (NBM) are shown. (B) Isolated CD34+ cells were stained with CXCR4-Fitc, or isotype control IgG-Fitc for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and the percentage of CXCR4-Fitc positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. The means of 9 MDS patients and 9 healthy donors are shown. (C) Isolated CD34+ cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL OregonGreen 514-Phalloidin. The fluorescence intensity of SDF-1-stimulated cells was determined by FACS analysis and presented as a percentage of that of unstimulated cells. The means of 8 MDS patients and 8 healthy controls (NBM) are shown.

Impaired SDF-1–induced F-actin polymerization of CD34+ cells

Several studies have suggested that the rate of F-actin polymerization might be limiting for cell migration.14,26 We therefore examined F-actin polymerization in response to SDF-1 in CD34+ cells from 8 MDS patients and 8 healthy controls. As shown in Figure 1C, SDF-1 stimulation of normal progenitors resulted in a rapid and transient polymerization of F-actin, with an optimum around 30 seconds. However, in MDS CD34+ cells, SDF-1-induced F-actin polymerization was significantly decreased compared with normal CD34+ cells (143 ± 6% vs 167 ± 8% at t = 30 seconds, P = .012; 113 ± 4% vs 131 ± 8% at t = 2 minutes, P = .012). These results indicate that impaired F-actin polymerization might be in part responsible for the impaired migration observed in MDS CD34+ cells in response to SDF-1.

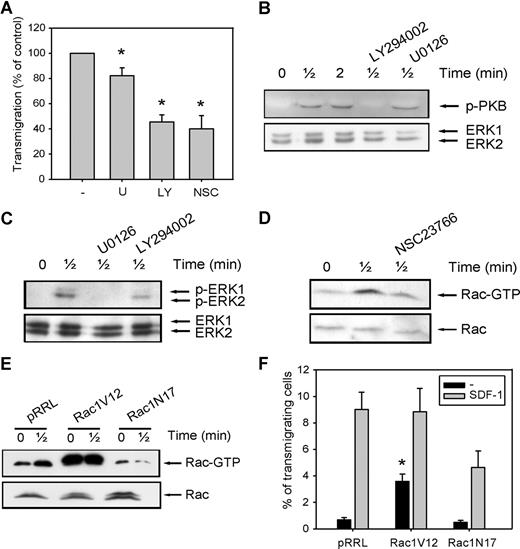

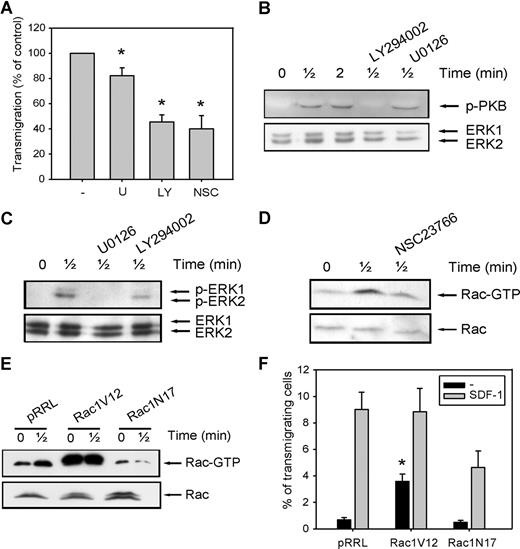

Dependence of SDF-1-induced migration on PI3K, ERK1/2, and the Rac GTPases

To further elucidate the mechanisms that might be responsible for the decreased migration of CD34+ cells in MDS patients, we investigated the involvement of the PI3K, ERK1/2, and Rac signaling pathways in migration of normal CD34+ cells toward SDF-1. As shown in Figure 2 A, pretreatment of normal CD34+ cells with the ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) led to a small decrease in the number of migrating cells compared with control cells (82 ± 6.3% of control, n = 6, P = .036), indicating that the ERK1/2 pathway is not the major signaling route important for migration toward SDF-1. We next investigated the involvement of PI3K in SDF-1-induced migration. Inhibition of this pathway with 10 μM LY294002 resulted in an attenuation of SDF-1-induced migration to 45 plus or minus 7% of that of control cells (n = 6, P = .001; Figure 2A). The effectiveness of U0126 and LY294002 in reducing the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and the PI3K target PKB, respectively, is shown in Figure 2B,C.

The involvement of PI2K, ERK1/2, and Rac in SDF-1-induced migration. (A) CD34+ cells from healthy donors were pretreated with 10 μM U0126, 10 μM LY294002, or 40 μM NSC23766 for 30 minutes, and applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 5-μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 4 hours at 37°C after which the transmigrated CD34+ cells were harvested from the lower chamber and counted by FACS analysis. The assay was done in duplicate, and the ratio between transmigrated CD34+ cells and the total amount of CD34+ cells added to the upper well was calculated. The number of cells migrated in the presence of inhibitors is shown as a percentage of the number of cells migrated in the control samples. The means of 6 individual experiments are shown. (B,C) Normal CD34+ cells were pretreated with 10 μM U0126 or 10 μM LY294002 for 30 minutes where indicated and subsequently stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1. PKB and ERK1/2 activation were detected by Western blotting, using antibodies against phosphorylated PKB or ERK1/2 (top). The blots were reprobed with total ERK1/2 antibody, to control for equal loading. Three independent experiments were performed, and one representative experiment is shown. (D) Normal CD34+ cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time, with or without pretreatment of cells with 40 μM NCS23766 for 30 minutes. Activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies. One representative example of 3 independent experiments is shown. (E) HL60 cells that were transduced with mock empty vector, Rac1V12 or Rac1N17 were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1. Activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies. One representative example of 3 independent experiments is shown. (F) HL60 cells that were transduced with mock empty vector, Rac1V12, or Rac1N17 were applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 8 μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 4 hours at 37°C after which the transmigrated cells were harvested from the lower chamber and counted by FACS analysis. The assay was done in duplicate, and the ratio between transmigrated HL60 cells and the total amount of cells added to the upper well was calculated. The means of 5 experiments are shown.

The involvement of PI2K, ERK1/2, and Rac in SDF-1-induced migration. (A) CD34+ cells from healthy donors were pretreated with 10 μM U0126, 10 μM LY294002, or 40 μM NSC23766 for 30 minutes, and applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 5-μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 4 hours at 37°C after which the transmigrated CD34+ cells were harvested from the lower chamber and counted by FACS analysis. The assay was done in duplicate, and the ratio between transmigrated CD34+ cells and the total amount of CD34+ cells added to the upper well was calculated. The number of cells migrated in the presence of inhibitors is shown as a percentage of the number of cells migrated in the control samples. The means of 6 individual experiments are shown. (B,C) Normal CD34+ cells were pretreated with 10 μM U0126 or 10 μM LY294002 for 30 minutes where indicated and subsequently stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1. PKB and ERK1/2 activation were detected by Western blotting, using antibodies against phosphorylated PKB or ERK1/2 (top). The blots were reprobed with total ERK1/2 antibody, to control for equal loading. Three independent experiments were performed, and one representative experiment is shown. (D) Normal CD34+ cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time, with or without pretreatment of cells with 40 μM NCS23766 for 30 minutes. Activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies. One representative example of 3 independent experiments is shown. (E) HL60 cells that were transduced with mock empty vector, Rac1V12 or Rac1N17 were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1. Activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies. One representative example of 3 independent experiments is shown. (F) HL60 cells that were transduced with mock empty vector, Rac1V12, or Rac1N17 were applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 8 μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 4 hours at 37°C after which the transmigrated cells were harvested from the lower chamber and counted by FACS analysis. The assay was done in duplicate, and the ratio between transmigrated HL60 cells and the total amount of cells added to the upper well was calculated. The means of 5 experiments are shown.

Another class of signaling molecules that has been implicated in cell motility and F-actin polymerization is that of the small Rho GTPases. Inhibition of Rac activity with the small molecule inhibitor NSC23766 (40 μM) abrogated SDF-1-induced migration to 40 plus or minus 11% of control cells (n = 6, P = .03; Figure 2A). The effectiveness of NSC23766 in reducing Rac activation is shown in Figure 2D. To confirm these results, we cloned constitutive active Rac1V12 and dominant negative Rac1N17 into the lentiviral vector pRRL-SFFV-GFP, and overexpressed these constructs in the SDF-1-responsive cell line HL60 by lentiviral transduction. Figure 2E shows that Rac was activated on SDF-1 stimulation of HL60 cells expressing the mock empty vector. In HL60 cells overexpressing Rac1V12, Rac activation was drastically enhanced, in both stimulated and unstimulated cells. In contrast, HL60 cells transduced with the dominant negative Rac1N17 showed a reduced Rac activation in response to SDF-1 stimulation.

We next investigated the migration of GFP positive cells toward SDF-1. When HL60 cells were transduced with the mock empty vector, 9 plus or minus 1.3% of GFP-positive cells migrated toward SDF-1 (Figure 2F). HL60 cells that overexpressed Rac1V12 did not show a significant increase in SDF-1–induced migration (9 ± 1.3% vs 9 ± 1.7%, P = .94, n = 5). However, a higher percentage of cells migrated in the absence of SDF-1 (0.7 ± 0.2% vs 3.6 ± 0.6%, P = .007, n = 5), suggesting that constitutive Rac activity does not increase directionality of migration but rather enhances random migration. In contrast, transduction of HL60 cells with dominant negative Rac1N17 decreased SDF-1–induced migration in 5 individual experiments (9 ± 1.3% vs 4.6 ± 1.3%, P = .028). In addition, SDF-1–induced migration was decreased in normal CD34+ cells lentivirally transduced with Rac1N17 compared with mock-transduced cells (15.2 ± 4% vs 3.5 ± 1%, n = 3, data not shown).

Taken together, these data clearly show that PI3K, and to a lesser extent ERK1/2, are required for movement of CD34+ cells toward SDF-1. Furthermore, the small GTPase Rac is essential for SDF-1–induced migration.

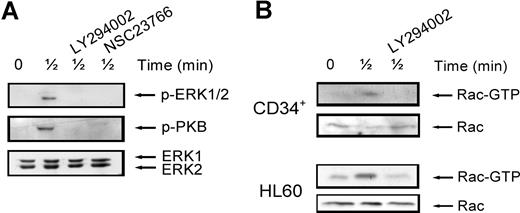

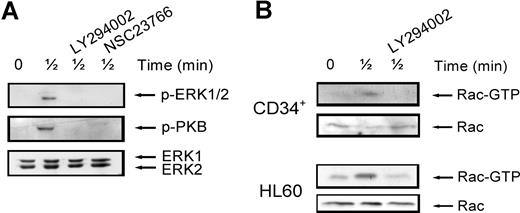

Interactions between signaling pathways

It is thought that interaction between individual signaling pathways may occur. For instance, ERK1/2 has been described to be dependent on PI3K signaling in some2,27 but not all systems.28 In addition, Rac has been shown to play a role in ERK1/2 activation, possibly through its target PAK.29,30 To establish whether this cross-talk between signaling pathways occurs in our system, we stimulated normal CD34+ cells with SDF-1 for 30 seconds, with or without pretreatment with the ERK1/2, PI3K and Rac inhibitors. As shown in Figure 3 A (top panel), ERK1/2 phosphorylation was attenuated by treatment of cells with either the PI3K inhibitor (3 of 4 experiments) or the Rac inhibitor (n = 2). Rac has also been shown to be activated in a PI3K-dependent manner.31 To test whether this was the case in HPCs, we studied Rac activation in normal CD34+ cells and HL60 cells. Figure 3B shows that Rac was activated after stimulation with SDF-1 for 30 seconds and that this activation could be inhibited by pretreatment of cells with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 in both HPCs and HL60 cells (n = 3). In addition, there have also been reports showing that Rac can in turn activate PI3K.32 Indeed, in our study, treatment of normal CD34+ cells with the Rac inhibitor NSC23766 attenuated PKB phosphorylation (Figure 3A middle). These results indicate that there is indeed cross-talk between SDF-1–stimulated signaling pathways. PI3K activates Rac, which in turn may activate both PI3K/PKB and ERK1/2 activity.

Interaction of signaling pathways. (A) Normal CD34+ cells were pretreated with 10 μM LY294002 or 40 μM NSC23766 for 30 minutes where indicated and subsequently stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1. ERK1/2 activation was detected by Western blotting, using antibodies against phosphorylated ERK1/2 (top) or PKB (middle). The blots were reprobed with total ERK1/2 antibody, to control for equal loading (bottom). One representative experiment is shown of 4 independent experiments. (B) Normal CD34+ cells or HL60 cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time, with or without pretreatment of cells with 10 μM LY294002 for 30 minutes. Activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (top panels). To compare the total amount of Rac protein in the samples, total lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (bottom panels). For both CD34+ and HL60 cells, one representative example of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Interaction of signaling pathways. (A) Normal CD34+ cells were pretreated with 10 μM LY294002 or 40 μM NSC23766 for 30 minutes where indicated and subsequently stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1. ERK1/2 activation was detected by Western blotting, using antibodies against phosphorylated ERK1/2 (top) or PKB (middle). The blots were reprobed with total ERK1/2 antibody, to control for equal loading (bottom). One representative experiment is shown of 4 independent experiments. (B) Normal CD34+ cells or HL60 cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time, with or without pretreatment of cells with 10 μM LY294002 for 30 minutes. Activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (top panels). To compare the total amount of Rac protein in the samples, total lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (bottom panels). For both CD34+ and HL60 cells, one representative example of 3 independent experiments is shown.

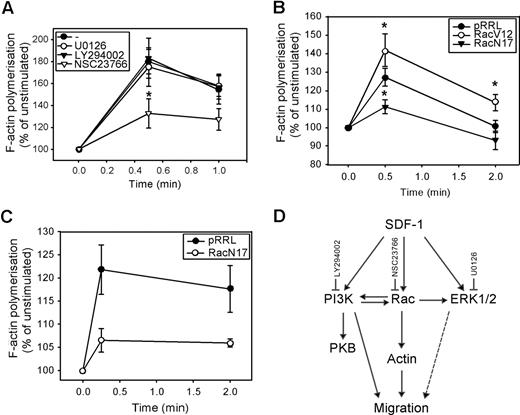

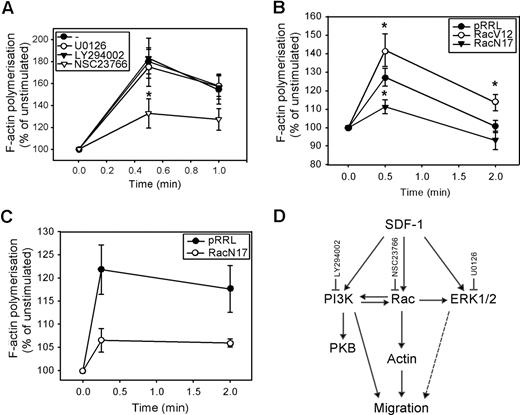

Involvement of PI3K, ERK1/2, Rac, and Rho in F-actin polymerization

We next investigated whether these signaling pathways were also involved in the polymerization of F-actin. As shown in Figure 4 A, neither U0126 nor LY294002 affected the SDF-1–induced F-actin polymerization in normal CD34+ cells (n = 5). However, pretreatment of CD34+ cells with the Rac inhibitor NSC23766 significantly attenuated actin assembly in response to SDF-1 (180 ± 11% vs 133 ± 13% at t = 30 seconds, P = .04; 158 ± 10% vs 127 ± 10% at t = 1 minute, n = 5, P = .09). We confirmed the involvement of Rac in SDF-1–induced F-actin polymerization, by showing that the rate of F-actin polymerization was increased in HL60 cells transduced with Rac1V12 compared with mock empty vector (125 ± 6% vs 142 ± 9% at t = 30 seconds, P = .035 and 101 ± 3% vs 114 ± 4% at t = 2 minutes, P = .042, n = 3; Figure 4B). Introducing Rac1N17 into HL60 cells significantly reduced the per-centage of F-actin polymerization (127 ± 5% vs 111 ± 4% at t = 30 seconds, P = .025, n = 4). In addition, SDF-1-induced F-actin polymerization in normal CD34+ cells overexpressing Rac1N17 was severely reduced compared with mock empty vector cells in 3 independent experiments (122 ± 5% vs 107 ± 3% at t = 10 seconds; 118 ± 5% vs 106 ± 1% at t = 2 minutes; Figure 4C).

The involvement of PI3K, ERK1/2, and Rac in SDF-1–induced F-actin polymerization. (A) CD34+ cells from healthy donors were pretreated with 10 μM U0126, 10 μM LY294002, or 40 μM NSC23766 for 30 minutes and stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL OregonGreen 514-Phalloidin. The fluorescence intensity was determined by FACS analysis and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. The mean of 5 independent experiments is shown. (B) HL60 cells were transduced with mock empty vector, Rac1V12 or Rac1N17, and GFP positive cells were sorted by MoFlow. Transduced cells were stimulated with SDF-1 for the indicated times, after which polymerized actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin. The fluorescence intensity was determined by FACS analysis, and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. The mean of 3 independent experiments is shown. Significant differences are indicated with an asterisk (P < .05). (C) Normal CD34+ cells (n = 3) were transduced with mock empty vector or Rac1N17. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin. Phalloidin binding in GFP + cells (ie, transduced cells) was determined by FACS analysis and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. (D) Schematic representation of the involvement of SDF-1–activated signaling pathways, and their cross-talk interactions, in migration and actin polymerization of normal CD34+ cells.

The involvement of PI3K, ERK1/2, and Rac in SDF-1–induced F-actin polymerization. (A) CD34+ cells from healthy donors were pretreated with 10 μM U0126, 10 μM LY294002, or 40 μM NSC23766 for 30 minutes and stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL OregonGreen 514-Phalloidin. The fluorescence intensity was determined by FACS analysis and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. The mean of 5 independent experiments is shown. (B) HL60 cells were transduced with mock empty vector, Rac1V12 or Rac1N17, and GFP positive cells were sorted by MoFlow. Transduced cells were stimulated with SDF-1 for the indicated times, after which polymerized actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin. The fluorescence intensity was determined by FACS analysis, and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. The mean of 3 independent experiments is shown. Significant differences are indicated with an asterisk (P < .05). (C) Normal CD34+ cells (n = 3) were transduced with mock empty vector or Rac1N17. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin. Phalloidin binding in GFP + cells (ie, transduced cells) was determined by FACS analysis and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. (D) Schematic representation of the involvement of SDF-1–activated signaling pathways, and their cross-talk interactions, in migration and actin polymerization of normal CD34+ cells.

These results implicate that, although ERK1/2, PI3K, and Rac are involved in CD34+ migration toward a SDF-1 chemotactic gradient, only Rac is necessary for F-actin polymerization in response to SDF-1. This would suggest that 2 separate pathways might be required for migration: a PI3K-dependent pathway and a PI3K-independent Rac-actin pathway. The pathways involved in SDF-1–induced migration and actin polymerization and the cross-talk between these pathways are shown in Figure 4D.

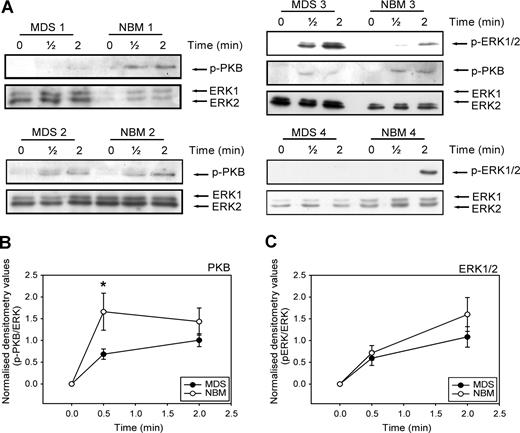

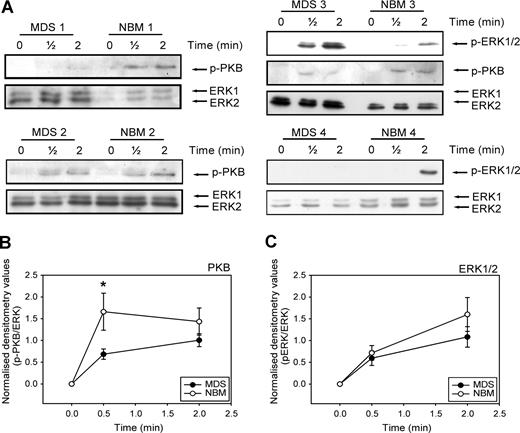

Activation of the PI3K and ERK1/2 pathways in MDS CD34+ cells

Activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K is required for full migration of CD34+ cells toward SDF-1. We wondered whether the disturbed migration of MDS CD34+ cells might be in part the result of an ineffective activation of these signaling molecules in the MDS cells. We therefore examined the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and the PI3K target PKB/Akt in CD34+ cells from 9 MDS patients compared with 9 healthy volunteers. Figure 5 A shows that stimulation of CD34+ cells with SDF-1 resulted in phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and the PI3K target PKB within 30 seconds in both MDS patients and healthy controls. However, in 7 of 9 patients, phosphorylation of PKB/Akt in response to SDF-1 was decreased compared with CD34+ lysates of healthy donors, run on the same Western blot. Three examples are shown in Figure 5A (MDS and NBM 1, 2, and 3). In Figure 5B, densitometry values of phosphorylated protein were divided by the densitometry values of ERK1/2 protein present in the same lanes. It is clear that PKB phosphorylation at 30 seconds of SDF-1 stimulation is significantly lower in MDS CD34+ compared with their healthy counterpart (0.7 ± 0.1 vs 1.9 ± 0.6, P = .04). In 4 of 9 patients, ERK1/2 phosphorylation was decreased, compared with normal controls. An example of normal ERK1/2 activation (MDS and NBM 3) and decreased ERK1/2 activation (MDS and NBM 4) are shown in Figure 5A. Overall, activation of ERK1/2 was not statistically different in MDS patients and healthy controls (Figure 5C). These results demonstrate that in MDS patients, SDF-1–induced PKB/Akt phosphorylation is impaired, resulting in a disturbed migration toward an SDF-1 gradient. In addition, in a number of patients ERK1/2 activation is reduced in response to SDF-1, which might contribute to an impaired migration toward SDF-1 in these patients.

Impaired SDF-1–induced PKB and ERK1/2 activation in MDS CD34+ cells. (A) Isolated CD34+ cells from 9 MDS patients and 9 healthy controls were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated times. Western blotting was performed using antibodies against phosphorylated PKB (p-PKB, top panels) or phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2, middle panels). To correct for loading differences the blots were reprobed with antibodies against ERK1/2 (bottom panels). 3 representative examples of PKB activation and 2 examples of ERK1/2 phosphorylation are shown. For quantification of phosphorylated PKB (B) and ERK1/2 (C), densitometry values were divided by the densitometry values of total ERK1/2 protein present in the same samples. Means of 9 independent experiments are shown. Significant differences are indicated with *(P < .05).

Impaired SDF-1–induced PKB and ERK1/2 activation in MDS CD34+ cells. (A) Isolated CD34+ cells from 9 MDS patients and 9 healthy controls were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated times. Western blotting was performed using antibodies against phosphorylated PKB (p-PKB, top panels) or phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2, middle panels). To correct for loading differences the blots were reprobed with antibodies against ERK1/2 (bottom panels). 3 representative examples of PKB activation and 2 examples of ERK1/2 phosphorylation are shown. For quantification of phosphorylated PKB (B) and ERK1/2 (C), densitometry values were divided by the densitometry values of total ERK1/2 protein present in the same samples. Means of 9 independent experiments are shown. Significant differences are indicated with *(P < .05).

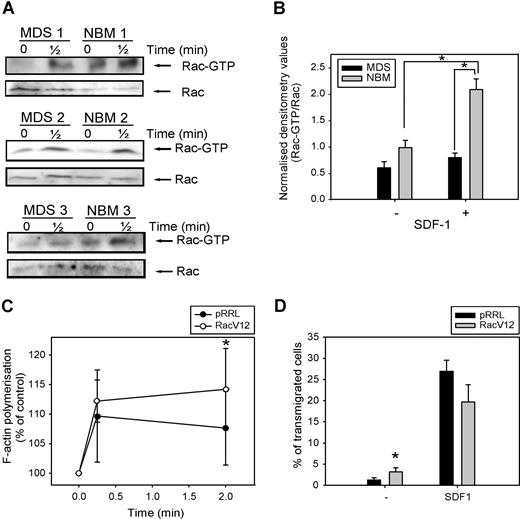

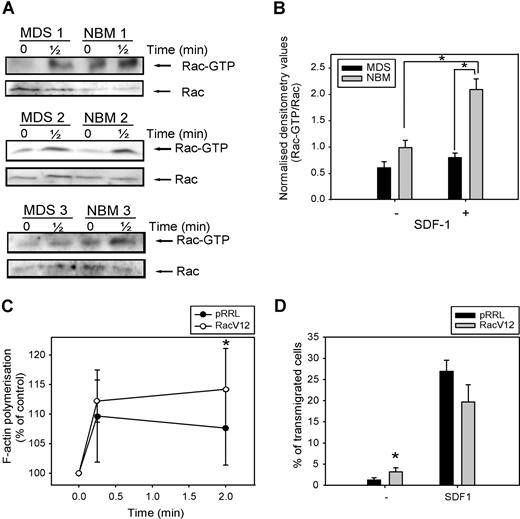

Activation of Rac in MDS CD34+ cells

As Rac is necessary for F-actin polymerization and migration of CD34+ cells, both of which are impaired in MDS patients, we investigated Rac activity in response to SDF-1 in 5 patients, compared with healthy controls. As depicted in Figure 6 A, Rac is activated in normal CD34+ cells on 30 seconds of SDF-1 stimulation. In MDS patients, the amount of activated Rac present in unstimulated CD34+ cells was slightly less compared with healthy controls, but densitometry of the blots revealed that this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 6B). Stimulation of MDS CD34+ cells with SDF-1 resulted in a slight increase in Rac activation, which did not reach statistical significance (0.6 ± 0.1 vs 0.8 ± 0.1, n = 5, P = .23). Furthermore, the amount of activated Rac present in SDF-1–stimulated cells from MDS patients, corrected for the total amount of Rac present in the samples, was significantly lower than in their healthy controls (2.1 ± 0.2 vs 0.8 ± 0.1, n = 5, P = .04).

Impaired SDF-1–induced Rac activation in MDS CD34+ cells. (A) MDS and normal CD34+ cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time and activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (top). To compare the total amount of Rac protein in the samples, total lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (bottom). Three representative examples of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) For quantification of active Rac, densitometry values of precipitated Rac were divided by the densitometry values of total Rac protein present in the same lysates. Means of 5 independent experiments are shown. Significant differences are indicated with an asterisk (P < .05). (C) MDS CD34+ cells (n = 4) were transduced with mock empty vector or Rac1V12. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin. Phalloidin binding in GFP + cells (ie, transduced cells) was determined by FACS analysis and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. (D) MDS CD34+ cells (n = 3) that were transduced with mock empty vector or Rac1V12 were applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 5-μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 4 hours at 37 °C after which transmigrated cells were harvested from the lower compartment and counted by FACS. The assay was done in duplicate and the ratio between transmigrated cells and total amount of cells added to the upper well was calculated. The mean of 3 experiments is shown.

Impaired SDF-1–induced Rac activation in MDS CD34+ cells. (A) MDS and normal CD34+ cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time and activated Rac was precipitated using GST-PAK-CRIB and visualized by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (top). To compare the total amount of Rac protein in the samples, total lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with Rac antibodies (bottom). Three representative examples of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) For quantification of active Rac, densitometry values of precipitated Rac were divided by the densitometry values of total Rac protein present in the same lysates. Means of 5 independent experiments are shown. Significant differences are indicated with an asterisk (P < .05). (C) MDS CD34+ cells (n = 4) were transduced with mock empty vector or Rac1V12. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for the indicated time. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with 2.5 U/mL Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin. Phalloidin binding in GFP + cells (ie, transduced cells) was determined by FACS analysis and expressed as a percentage of that in unstimulated cells. (D) MDS CD34+ cells (n = 3) that were transduced with mock empty vector or Rac1V12 were applied to the upper compartment of a microchamber transwell system with 5-μm pores. Migration was induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 4 hours at 37 °C after which transmigrated cells were harvested from the lower compartment and counted by FACS. The assay was done in duplicate and the ratio between transmigrated cells and total amount of cells added to the upper well was calculated. The mean of 3 experiments is shown.

In view of the impaired Rac activation in MDS CD34+ cells, we wondered whether restoration of Rac activity might restore F-actin polymerization in these cells. We therefore transduced CD34+ cells from 3 MDS patients with either mock empty vector or Rac1V12, and measured SDF-1–induced F-actin polymerization. As depicted in Figure 6C, MDS CD34+ cells overexpressing Rac1V12 showed a significantly higher F-actin polymerization in response to SDF-1 stimulation compared with mock-transduced cells (110 ± 8% vs 112 ± 4% at t = 10 seconds; 108 ± 6% vs 114 ± 7% at t = 2 minutes, n = 3, P = .048).

We next investigated the migratory capacity of MDS CD34+ cells transduced with Rac1V12 or empty vector. As was shown for HL60 cells in Figure 2F, Figure 6D indicates that transduction of MDS progenitor cells with Rac1V12 did not result in an increased migration toward SDF-1 compared with mock-transduced cells (27 ± 3% vs 20 ± 4%, n = 3, P = .1). However, the number of cells present in the lower compartment of the Transwell assay in the absence of SDF-1 was significantly increased in Rac1V12 transduced cells compared with mock- transduced cells (1.2 ± 0.5% vs 3.2 ± 1%, n = 4, P = .03). These results indicate that motility of cells, but not directional migration, could be increased in MDS CD34+ cells on overexpression of constitutive active Rac1. Taken together, these studies suggest that Rac activation is impaired in SDF-1-triggered CD34+ cells from MDS patients and that restoration of Rac activity can significantly improve their function.

Discussion

Proper localization of hematopoietic stem cells within their microenvironment is imperative for the development of normal hematopoiesis. SDF-1 has been shown to play a major role in homing and retention of progenitor cells within the bone marrow (reviewed in Dar et al33 ). In addition, in vitro migration capacity toward SDF-1 is an important parameter for the homing and hematopoietic reconstitution capacity of human progenitor cells.34 The present study demonstrates a significant impairment in migration of CD34+ cells from MDS patients toward SDF-1. The mean age of the MDS patient cohort in this study was slightly lower than the average age of MDS patients, which might be due to an involuntary selection for patient samples with enough cells for analysis. As cellular responses seem to deteriorate with age,35 this could mean an underestimation of the defects observed in the present study. The role of the actin cytoskeleton in cell migration has been well described and is a prerequisite for normal migration. We now show that F-actin polymerization is impaired in MDS CD34+ cells. The most intensively studied signaling molecules involved in migration and actin polymerization are the small GTPases RhoA, Rac1/2, and Cdc42 (reviewed in Hall36 ). Studies from Rac deficient mice have shown that both Rac1 and Rac2 play important roles in homing and engraftment of hematopoietic progenitor cells (reviewed in Cancelas et al37 ). In accordance, transduction of mouse hematopoietic progenitor cells with dominant negative Rac2 results in a decreased in vitro migration and engraftment of these cells.38 Comparable results have been obtained with cord-blood CD34+ cells.39 We used lentiviral transduction of dominant negative Rac1 to show that Rac plays an important role in SDF-1–induced F-actin polymerization and migration of human CD34+ and HL60 cells. A role for Rac2 cannot be excluded, however, as these dominant negative constructs might not be selective for Rac1; they act by binding to gua-nine nucleotide exchange factors that can activate both Rac1 and Rac2.40

In this study, we also show that the PI3K pathway plays an important role in SDF-1–induced migration of human CD34+ cells, confirming reports by others.18,22 Many studies have reported cross-talk between Rho-GTPases and PI3K,17,41,42 and we now show that Rac activation is dependent on PI3K activity in CD34+ cells stimulated with SDF-1. However, we did not find a decreased polymerization of F-actin in response to SDF-1 stimulation on inhibition of PI3K. This might be because F-actin polymerization occurs in 2 phases: an initial rapid phase, resulting in a peak of actin polymerization as shown in Figure 2, and a second slow phase, which is not represented in our system. The rapid phase is PI3K independent, whereas the slower phase is relatively more sensitive to PI3K inhibition.43 However, both phases can be assumed to be dependent on Rac activity, explaining why we find Rac to be attenuated in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor without an effect on the rapid F-actin polymerization. To complicate matters further, Rac also has an effect on PI3K activity in migrating cells.32 We show that in MDS patients, both SDF-1–induced PI3K and Rac activity are impaired. That these defects contribute to the decreased migration and F-actin polymerization in these patients seems certain, but whether the defects occur in 1 pathway or 2 independent pathways remains to be established. Interestingly, it has recently been reported that SDF-1 induces activation of the adaptor molecule Crk-L in a PI3K-dependent manner.22 Furthermore, Crk-L is involved in migration of cells through activation of both Rac and ERK1/2.44 In addition to PI3K and Rac, we found a decreased activation of ERK1/2 in some of the patients, which was partially PI3K and Rac dependent. The above studies suggest that the signaling impairments observed in MDS might be the result of a defect in just one interlinking pathway, which was not a result of decreased CXCR4 receptor expression. This would make this pathway an attractive candidate for intervention therapies. Our studies show that overexpression of constitutive active Rac1 can result in partial restoration of SDF-1–induced cell function in MDS. However, we did not find an effect on SDF-1–induced migration in MDS cases. A possible explanation might be that ectopic expression of Rac1 can disrupt the “frontness” and “backness” in polarized cells, thereby reducing gradient oriented migration. Careful regulation of the level of expression of GTPases might be required to improve migrational function of cells. In addition, it cannot be excluded that culturing MDS cells before transduction leads to selection of stronger cells, resulting in a population of cells that migrate relatively well. Our results indicate that, although directional migration does not benefit from Rac1V12 overexpression, nondirectional migration in the absence of SDF-1 is increased in both HL60 cells and MDS CD34+ cells. Furthermore, other signaling pathways might also be involved. For instance, in addition to Rac, other RhoGTPases are essential for migration. It has recently been described that RhoH, a hematopoietic-specific constitutive active GTPase, is involved in Rac activation, F-actin polymerization, and migration of hematopoietic progenitor cells.45

Interestingly, we have previously found that in MDS patients, IL-8 induced activation of PI3K, ERK1/2, and Rac was impaired in neutrophils, resulting in a defective migration of these cells.3 Our current studies suggest that these defects are already present in early hematopoietic progenitors and carried on throughout the differentiation. Decreased expression and function of CXCR4 result in impaired migration of bone marrow progenitor cells in vitro and reduced myelopoiesis in vivo.46 It is possible that a migration defect in MDS CD34+ cells results in improper localization within the bone marrow and consequently to a reduced hematopoietic potential and defective release of cells to the peripheral blood. The described impairment in the SDF-1-mediated effects might also contribute to the reduced stem–cell mobilization in response to growth factor stimulation that is often observed in MDS patients.

We recently found an impaired formation of lipid rafts in neutrophils from MDS patients.47 Lipid rafts are cholesterol-enriched microdomains within the plasma membrane, thought to facilitate receptor-mediated signal transduction. In migrating neutrophils, PI3K activity colocalizes with lipid rafts at the leading edge of the cell,17 and on disruption of lipid rafts, cells are no longer are able to sense a gradient of chemoattractant resulting in loss of migration potential.48 Lipid rafts are also present in CD34+ progenitor cells, and polarize on stimulation of these cells with SDF-1.49 In addition, upon SDF-1-induced chemotaxis, the CXCR4 receptor localizes at the leading edge of the cell where it colocalizes with these lipid rafts.50,51 Disruption of lipid rafts with methyl-β-cyclodextrin abrogates SDF-1-induced migration of normal CD34+ cells (our unpublished results). It is therefore of interest to investigate a possible role for disturbed raft formation in the impaired signaling and migration of SDF-1–stimulated MDS CD34+ cells.

In conclusion, our results indicate an impaired SDF-1–induced activation of PI3K and Rac in MDS CD34+ cells, resulting in a decreased F-actin polymerization and subsequent migration toward this chemoattractant.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients and healthy volunteers who participated in this study.

This work was supported by grant RUG 2003-2929 from the Dutch Cancer Society (P.J.C. and E.V.).

Authorship

Contribution: G.M.F. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments and wrote the paper; A.L.D. designed experiments and analyzed the data; S.G.M.O. performed experiments; J.J.S. contributed vital analytical tools; and P.J.C. and E.V. designed the research and analyzed the data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Edo Vellenga, Hanzeplein 1, 9713 GZ Groningen, the Netherlands; e-mail: E.Vellenga@int.umcg.nl.