Abstract

Whether leukocytes exert an influence on vascular function in vivo is not known. Here, genetic and pharmacologic approaches show that the absence of neutrophils leads to acute blood pressure dysregulation. Following neutrophil depletion, systolic blood pressure falls significantly over 3 days (88.0 ± 3.5 vs 104.0 ± 2.8 mm Hg, day 3 vs day 0, mean ± SEM, P < .001), and aortic rings from neutropenic mice do not constrict properly. The constriction defect is corrected using l-nitroarginine-methyl ester (L-NAME) or the specific inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibitor 1400W, while acetylcholine relaxation is normal. iNOS- or IFNγ-deficient mice are protected from neutropenia-induced hypotension, indicating that iNOS-derived nitric oxide (NO) is responsible and that its induction involves IFNγ. Oral enrofloxacin partially inhibited hypotension, implicating bacterial products. Roles for cyclooxygenase, complement C5, or endotoxin were excluded, although urinary prostacyclin metabolites were elevated. Neutrophil depletion required complement opsinization, with no evidence for intravascular degranulation. In summary, circulating neutrophils contribute to maintaining physiological tone in the vasculature, at least in part through suppressing early proinflammatory effects of infection. The speed with which hypotension developed provides insight into early changes that occur in the absence of neutrophils and illustrates the importance of constant surveillance of mucosal sites by granulocytes in healthy mice.

Introduction

Circulating neutrophils interact with the vessel wall through the action of adhesion molecules including P- and L-selectins. Although the mechanisms by which they bind to endothelium, roll, adhere, and extravasate are understood, whether neutrophils themselves exert functional influences on the vessel wall itself has not been studied in vivo. There are several potential mechanisms by which these cells may regulate vascular function in vivo. On activation of NADPH oxidase (respiratory burst), they generate superoxide (O2·−), a reactive oxygen species that reacts with nitric oxide (NO), the primary mediator of endothelium-dependent relaxation in large vessels.1,2 NADPH oxidase–mediated NO consumption occurs immediately on activation of neutrophils by fMLP, and rates of NO removal are 2- to 3-fold greater than corresponding O2·−-generation rates.3 This could have significant consequences for the ability of NO to maintain vascular tone in vivo, especially during inflammation. Reaction of NO with O2·− forms peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a powerful oxidant and nitrating agent that may itself lead to vascular dysfunction through protein and lipid modification, and thiol depletion.1 ONOO− nitrates prostacyclin synthase, the enzymatic source of another important endothelial-derived vasorelaxant, prostacyclin (PGI2).4,5 Neutrophils also may remove NO indirectly through myeloperoxidase (MPO)–catalyzed reactions. Following degranulation, MPO binds to the endothelium where it can potentially remove NO during peroxidase turnover.6,7 Apart from direct oxidative reactions, neutrophils could influence vascular function through release of mediators that exert direct vasoactive effects, including cytokines, adenosine, proteases, and phospholipases. Finally, through interactions with adhesion molecules they may activate endothelial signal transduction, although this is less well understood

Previous experiments have addressed the idea that neutrophils may modulate vascular function by examining vascular tone in isolated aortic rings in vitro. Addition of activated neutrophils prevented or reversed endothelium-dependent relaxation or elicited a O2·−-dependent vasoconstriction of rabbit or cat arteries, consistent with a role for oxidative inactivation of NO by the cells.8,9 Separately, other studies implicated prostaglandins or leukotrienes in the vasoconstrictive effect of neutrophils.10,11 However, studies have not addressed the ability of neutrophils to modulate vascular function in vivo. To address this, we used a well-characterized murine model of neutropenia involving intraperitoneal injection of anti–GR-1.12,13 Genetic and pharmacologic approaches were used to determine the influence of neutrophils on blood pressure and in vitro vascular function in otherwise healthy mice.

Methods

Animal studies

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the United Kingdom Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Eight- to 10-week-old, male wild-type BALB/c, IFNγ−/− BALB/c, C3−/− C57Bl/6, inducible nitric oxide synthase–deficient (iNOS−/−) C57Bl/6, and C57Bl/6 mice (Charles River, Kent, United Kingdom) were kept in constant temperature cages (20-22°C) and given free access to water and standard chow.14-16 Celecoxib was given in chow (400 mg/kg per day); enrofloxacin (Dunlop's Veterinary Supplies, Dumfries, United Kingdom) was given in drinking water (0.4 g/L). All experiments, except for iNOS−/−, C3−/−, and their controls were performed using Balb/C mice. Controls for these 2 strains were age- and sex-matched C57BL/6 mice.

Neutrophil depletion

Neutrophils were depleted using the antibody RB6-8C5, a rat anti–mouse IgG2b directed against Ly-6G, previously known as Gr-1, an antigen on the surface of mouse neutrophils.17 The antibody was prepared for injection by dilution with sterile PBS under aseptic conditions. Doses were 150 μg on day 0 and 300 μg on days 2, 4, and 6. Alternatively, mice received an equal dose of a control antibody, GL113.

Blood pressure measurement

Systolic blood pressure (BP) was measured daily at the same time of day, for 3 to 5 days before neutrophil depletion (training) and for 8 days after depletion, by tail-cuff plethysmography (Duo 18; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). All BP measurements were carried out at 24°C to 26°C.

Isometric tension functional studies

Male control or neutrophil-depleted mice (8-10 weeks old) were killed by asphyxiation. The thoracic aorta was removed and placed in Krebs-Henseleit buffer. The aorta was dissected of adipose tissue, cut into rings (2-3 mM), and suspended in an isometric tension myograph (model 610; DMT, Aarhus, Denmark) containing Krebs-Henseleit buffer (120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 24 mM NaHCO3, 1.1 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM glucose, 2.5 mM CaCl2.2H2O, pH 7.4) at 37°C and gassed at 5% CO2/95% O2. A resting tension of 3 mN was maintained, and changes in isometric tension were recorded via Myodaq software (DMT). After a 60-minute equilibration period, vessels were primed with 48 mM KCl before a concentration (0.1 μM) of phenylephrine (PE) producing approximately 75% contraction was added. Once responses stabilized, 1 μM acetylcholine (ACh) was added to assess endothelial integrity. Any rings that did not maintain contraction to PE, or relaxed less than 50% of the PE-induced tone after addition of ACh (1 μM) were discarded. No differences in the number of rings discarded between wild-type and neutrophil-depleted vessels were observed. Rings were washed for 30 minutes, after which a cumulative concentration-response curve to PE was constructed (1 nM to 0.1 mM) to assess vasoconstrictor activity. The tissues were then washed for 60 minutes to restore basal tone before contracting to approximately 80% of the 0.1 mM PE-induced response. Once a stable response to PE was observed, cumulative concentration response curves were constructed to ACh (1 nM to 10 μM), and then after a 30-minute wash, to DEA-NONOate (0.1 nM to 0.1 mM; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI), to assess endothelium-dependent and -independent relaxations, respectively. Experiments were repeated in the presence of either 300 μM l-nitroarginine-methyl ester (L-NAME) or 10 μM 1400W, with constriction and dilation curves being constructed as described previously. Responses were expressed as a percentage of either baseline tension (vasoconstriction) or contracted tension (vasodilation). Responses from patent rings of each animal (3-4 rings) were combined to produce an average for each (n).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as described previously.18,19 Leukocytes were prepared from control blood by hypotonic lysis of whole blood. Cells were concentrated by centrifugation and resuspended in a small volume of PBS containing protease inhibitors (Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor cocktail tablets; Roche Diagnostics, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom). Samples were then assayed for concentration before being diluted into sample buffer. For Western blotting of MPO, samples (1.5 μg leukocytes, or plasma from control or neutropenic mice) were probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-MPO antibody (1:1000; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) after incubation with a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antirabbit secondary antibody (1:20 000).

Immunohistochemistry

The descending thoracic aorta was removed, cleaned of adipose tissue, and fixed in paraffin wax. Sections (10 μm each) were taken using a microtome and methanol-fixed on glass slides, permeabilized using 0.1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100/PBS, and blocked using 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS. MPO or iNOS expression was visualized using either rabbit anti-MPO (1:200) or rabbit anti-iNOS (1:50; Calbiochem, Merck Biosciences, Nottingham, United Kingdom), with goat anti–rabbit IgG-Alexa 568 as secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Negative controls were equivalent concentrations of isotype control rabbit IgG antibody (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). Imaging was performed on an Axiovert S100 TV inverted microscope connected to a Hamamatsu Orca I/ER 4742-95 camera (Hamamatsu Photonics UK, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom) or a Bio-Rad MRC 1024ES laser scanning system (Bio-Rad Microscience, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) using standard analysis software (Lasersharp 2000; Bio-Rad Microscience). Confocal images were acquired using a 10× air lens, with excitation at 568 nM and emission 595/35 nM. Postacquisition processing used Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), with average fluorescence intensity of specific stained regions (arbitrary units) of unprocessed images determined using Lasersharp 2000 or AQM-advance 6 (Kinetic Imaging, Wirral, United Kingdom). For each aorta, 5 separate sections were imaged and pixel intensity calculated at 5 separate areas of each section. Therefore, for each aorta, typically 25 separate pixel intensity determinations were made.

Stable isotope-dilution gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

Urine was collected in metabolic cages over a 24-hour period from control and neutropenic (day 2 to day 3) Balb/c mice. Four mice were kept in each cage and the urine from these was pooled to generate a single sample (n = 3 separate cages). Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) was used to detect and quantify the presence of the prostacyclin metabolite 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α (2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α).20

Inhibition of complement in vivo

BPs were measured in wild-type Balb/c mice administered RB6-8C5 with or without coadministration of the anticomplement C5 antibody BB5.1 (1 mg intraperitoneally, day 0 and day 2). BB5.1 was also administered alone as a control.

Comparing complement-activating capacity of mAb RB6-8C5 with the control

GL113, RB6-8C5 is a rat IgG2b antibody, an isotype previously reported to be complement activating.21 To determine mouse complement-activating capacity in vitro, plates (96-well; Nunclon Maxisorb; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with a Fab fragment of a polyclonal anti–rat IgG (made in house) at 10 μg/mL in carbonate buffer (pH 8.0) blocked in PBS containing 0.1% tween-20 (PBS-T) and 1% BSA, and incubated with mAb RB6-8C5 or the control mAb GL113 at 0.05 mg/mL (a dose shown to saturate the capture antibody in preliminary titrations) in PBS-T. Unbound antibody was removed by washing 4 times in PBS-T and blotting wells dry, and dilutions of mouse serum in veronal-buffered saline (CFD; Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) were added to the wells in triplicate. Plates were incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C, washed in PBS-T, and incubated with biotinylated rabbit anti–human C3 IgG (10 μg/mL in PBS-T; made in house, known cross-reactivity with mouse C3) for 30 minutes at 4°C. After washing, plates were incubated with avidin-peroxidase (Bio-Rad Microscience; 1:1000 in PBS-T), washed, and developed using OPD substrate. Absorbance values were read at 490 nm in a Dynex (Chantilly, VA) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader.

LPS assay

Mouse plasma was assayed for endotoxin by the Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) test.22 Briefly, mouse blood was obtained into a heparinized syringe by cardiac puncture and centrifuged at 10 000g for 5 minutes at 4°C to recover plasma. Plasma was diluted 1:10 in endotoxin-free water (Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA) and heated at 75°C for 5 minutes. Plasma (50 μL) was then incubated with 50 μL pyrochrome working solution (Associates of Cape Cod) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 0.05 mL nitrite in HCl and endotoxin visualized by addition of ammonium sulfate and NEDA. Endotoxin concentrations were quantified by measuring absorbance at 548 nM and compared with standard curves generated with endotoxin stock dilutions (0.5-0.016 EU/mL).

Results

RB6-8C5 specifically depletes neutrophils in mice

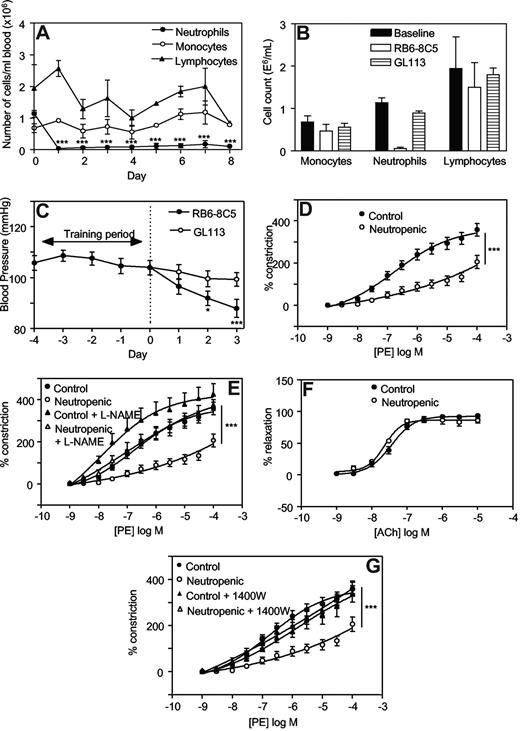

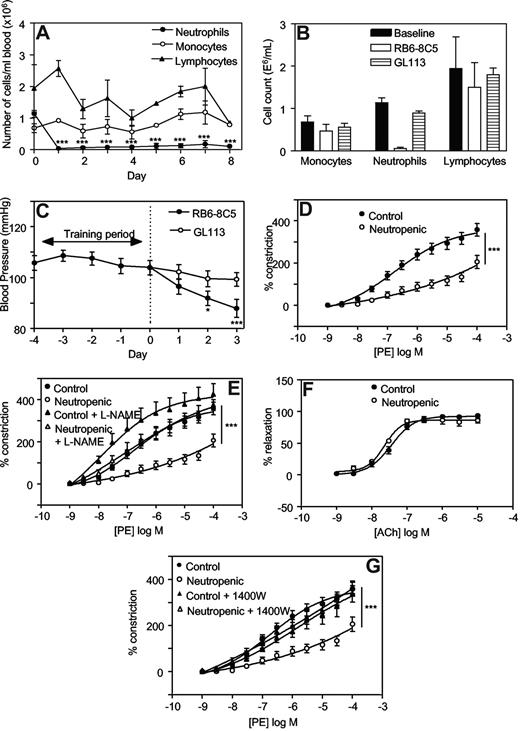

One day after injection with RB6-8C5, neutrophil counts had decreased significantly (eg, 0.04 ± 0.03 × 106 cells/mL vs 1.1 ± 0.1 × 106 cells/mL, day 1 vs day 0, mean ± SEM, P < .001, n = 3) and remained depleted for up to 8 days (Figure 1A). The monocyte or lymphocyte counts did not change significantly. These data confirm that RB6-8C5 specifically depletes neutrophils without affecting monocyte or lymphocyte numbers as previously shown.23 Administration of an equal dose of a control antibody, GL113, did not result in any significant change in circulating leukocytes (Figure 1B).

Injection of RB6-8C5 causes specific depletion of neutrophils and decreases blood pressure and vascular tone in Balb/C mice, in an iNOS-dependent manner. (A) Induction of neutropenia following intraperitoneal injection of RB6-8C5. RB6-8C5 was administered by intraperitoneal injection, 150 μg on day 0 and 300 μg on days 2, 4, and 6. Differential counts were performed on whole blood (n = 3, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001 vs day 0 using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett posthoc test analysis. (B) Control antibody does not cause neutropenia. Differential counts were performed on whole blood from mice administered either RB6-8C5 or GL113, following 3 days of neutropenia. (C) Depletion of neutrophils causes progressive hypotension. Blood pressures were measured daily by tail-cuff plethysmography, in mice administered either RB6-8C5 or an equal dose of GL113 intraperitoneal (n ≥ 15 for RB6-8C5 and n ≥ 10 for GL113, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001, *P < .05 versus day 0 using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett posthoc test analysis. (D) Thoracic aortae from neutropenic mice display reduced vasoconstriction responses. PE-induced constriction dose-response curves were constructed in thoracic aortae from control mice and mice depleted of neutrophils for 3 days using myography (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001 vs control using 2-way ANOVA. (E) L-NAME restores constriction to control levels in aortae from neutropenic mice. Dose-responses curves to PE were determined in thoracic aortae from control mice and mice depleted of neutrophils for 3 days in the presence or absence of 300 μM L-NAME (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001, neutropenic plus L-NAME versus neutropenic using 2-way ANOVA. (F) Acetylcholine relaxation is normal in aortae from neutropenic mice. Relaxation dose-response curves to ACh in PE-preconstricted aortae from control and neutropenic mice (day 3) were constructed (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). (G) 1400W restores constriction to control levels in aortae from neutropenic mice. PE-induced constriction responses in aortae from control and neutropenic mice (day 3) in the presence or absence of 10 μM 1400W were constructed (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001, neutropenic plus 1400W versus neutropenic using 2-way ANOVA.

Injection of RB6-8C5 causes specific depletion of neutrophils and decreases blood pressure and vascular tone in Balb/C mice, in an iNOS-dependent manner. (A) Induction of neutropenia following intraperitoneal injection of RB6-8C5. RB6-8C5 was administered by intraperitoneal injection, 150 μg on day 0 and 300 μg on days 2, 4, and 6. Differential counts were performed on whole blood (n = 3, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001 vs day 0 using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett posthoc test analysis. (B) Control antibody does not cause neutropenia. Differential counts were performed on whole blood from mice administered either RB6-8C5 or GL113, following 3 days of neutropenia. (C) Depletion of neutrophils causes progressive hypotension. Blood pressures were measured daily by tail-cuff plethysmography, in mice administered either RB6-8C5 or an equal dose of GL113 intraperitoneal (n ≥ 15 for RB6-8C5 and n ≥ 10 for GL113, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001, *P < .05 versus day 0 using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett posthoc test analysis. (D) Thoracic aortae from neutropenic mice display reduced vasoconstriction responses. PE-induced constriction dose-response curves were constructed in thoracic aortae from control mice and mice depleted of neutrophils for 3 days using myography (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001 vs control using 2-way ANOVA. (E) L-NAME restores constriction to control levels in aortae from neutropenic mice. Dose-responses curves to PE were determined in thoracic aortae from control mice and mice depleted of neutrophils for 3 days in the presence or absence of 300 μM L-NAME (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001, neutropenic plus L-NAME versus neutropenic using 2-way ANOVA. (F) Acetylcholine relaxation is normal in aortae from neutropenic mice. Relaxation dose-response curves to ACh in PE-preconstricted aortae from control and neutropenic mice (day 3) were constructed (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). (G) 1400W restores constriction to control levels in aortae from neutropenic mice. PE-induced constriction responses in aortae from control and neutropenic mice (day 3) in the presence or absence of 10 μM 1400W were constructed (n ≥ 4, mean ± SEM). ***P < .001, neutropenic plus 1400W versus neutropenic using 2-way ANOVA.

Neutrophil depletion causes progressive hypotension and aortic constriction defect in mice

Administration of RB6-8C5 was associated with a significant fall in systolic blood pressure (BP) over 3 days (104.0 ± 2.8 mm Hg vs 88.0 ± 3.5 mm Hg, on day 0 and day 3, respectively, mean ± SEM, P < .001, n ≥ 15; Figure 1C). In contrast, intraperitoneal administration of a control antibody (GL113) had no effect on BP (99.3 ± 2.8 mm Hg vs 104.0 ± 2.8 mm Hg on day 3 and day 0, respectively, mean ± SEM, P = .260, n ≥ 10; Figure 1C). Between days 4 to 7, significant rises in BP were seen with both RB6-8C5 and GL113, suggesting that administration of antibody per se may cause side-effects (eg, by immune complex formation; data not shown). In vitro, aortae from neutropenic mice (day 3) exhibited a significant attenuation in phenylephrine (PE)–induced vasoconstriction compared with controls (Figure 1D). These data show defects in vasoconstriction both in vivo and in vitro.

Elevated iNOS is responsible for the decreased BP and vasoconstriction in neutropenic mice

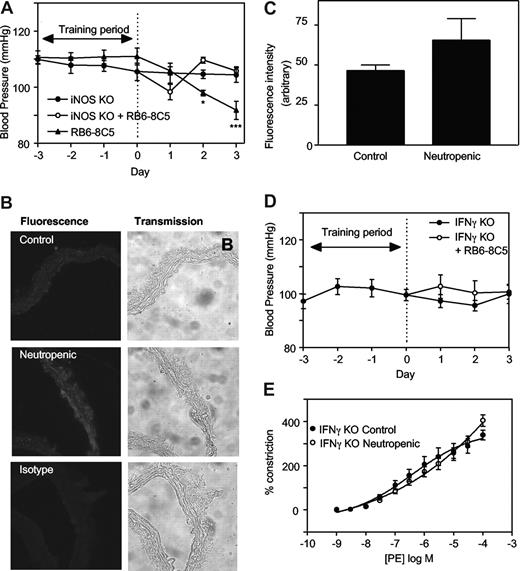

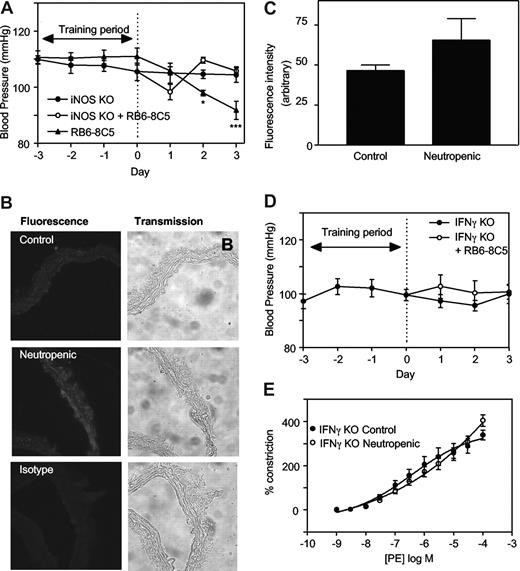

To explore the mechanisms involved, regulation of tone by aortae from control and neutropenic mice (day 3) were compared in the presence of signaling inhibitors. Preincubation of aortic rings from healthy mice with the nonspecific NOS inhibitor L-NAME (300 μM, 15 minutes) slightly but not significantly enhanced vasoconstriction to PE (Figure 1E). In contrast, aortae from neutrophil-depleted animals exhibited a significantly enhanced vasoconstriction to PE in the presence of L-NAME (Figure 1E). Indeed, L-NAME normalized vasoconstriction of rings from neutropenic animals to levels comparable with healthy controls. Endothelial-dependent relaxation to ACh was unaffected by neutropenia indicating that eNOS bioactivity is unchanged (Figure 1F). However, a role for iNOS is indicated since the specific inhibitor 1400W (10 μM, 30 minutes) normalized PE constriction, similar to L-NAME (Figure 1G). Furthermore, in vivo deletion of iNOS totally prevented the neutropenia-dependent fall in systolic BP (Figure 2A). Finally, using immunohistochemistry, an increase in iNOS staining was seen to colocalize with smooth muscle fibers in neutropenic vessels (Figure 2B,C).

iNOS- or IFNγ-deficient mice are resistant to the hypotensive effects of neutropenia. (A) iNOS knockout mice are resistant to the hypotensive effects of neutrophil depletion. Blood pressure measurements were carried out in iNOS−/− C57BL/6 mice with/without administration of RB6-8C5 (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM). Controls are age- and sex-matched wild-type C57Bl/6. (B) Induction of iNOS during neutropenia in wild-type mice. Thoracic aortic sections from control and neutropenic wild-type mice (day 3) were sectioned and stained for iNOS. Representative sections are shown for each condition. (C) Pixel intensity was determined after fluorescence staining of aortic sections (n = 3 separate aortae, with 25 determinations per aorta). (D) IFNγ knockout mice are resistant to the hypotensive effects of neutrophil depletion. Blood pressure measurements in IFNγ−/− Balb/C mice with/without administration of RB6-8C5 (n ≥ 6, mean ± SEM). (E) IFNγ−/− mice do not show decreased PE constriction following RB6-8C5 administration. PE-induced constriction responses in thoracic aortae from control IFNγ−/− mice and IFNγ−/− mice depleted of neutrophils for 3 days (n ≥ 6, mean ± SEM). Aortic ring functional responses were determined.

iNOS- or IFNγ-deficient mice are resistant to the hypotensive effects of neutropenia. (A) iNOS knockout mice are resistant to the hypotensive effects of neutrophil depletion. Blood pressure measurements were carried out in iNOS−/− C57BL/6 mice with/without administration of RB6-8C5 (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM). Controls are age- and sex-matched wild-type C57Bl/6. (B) Induction of iNOS during neutropenia in wild-type mice. Thoracic aortic sections from control and neutropenic wild-type mice (day 3) were sectioned and stained for iNOS. Representative sections are shown for each condition. (C) Pixel intensity was determined after fluorescence staining of aortic sections (n = 3 separate aortae, with 25 determinations per aorta). (D) IFNγ knockout mice are resistant to the hypotensive effects of neutrophil depletion. Blood pressure measurements in IFNγ−/− Balb/C mice with/without administration of RB6-8C5 (n ≥ 6, mean ± SEM). (E) IFNγ−/− mice do not show decreased PE constriction following RB6-8C5 administration. PE-induced constriction responses in thoracic aortae from control IFNγ−/− mice and IFNγ−/− mice depleted of neutrophils for 3 days (n ≥ 6, mean ± SEM). Aortic ring functional responses were determined.

Neutropenia-dependent hypotension requires IFNγ signaling

Neutrophil depletion requires complement C3 but not C5, and does not result in intravascular degranulation of neutrophils

To further understand the mechanisms involved, the role of complement and intravascular neutrophil activation was tested as follows.

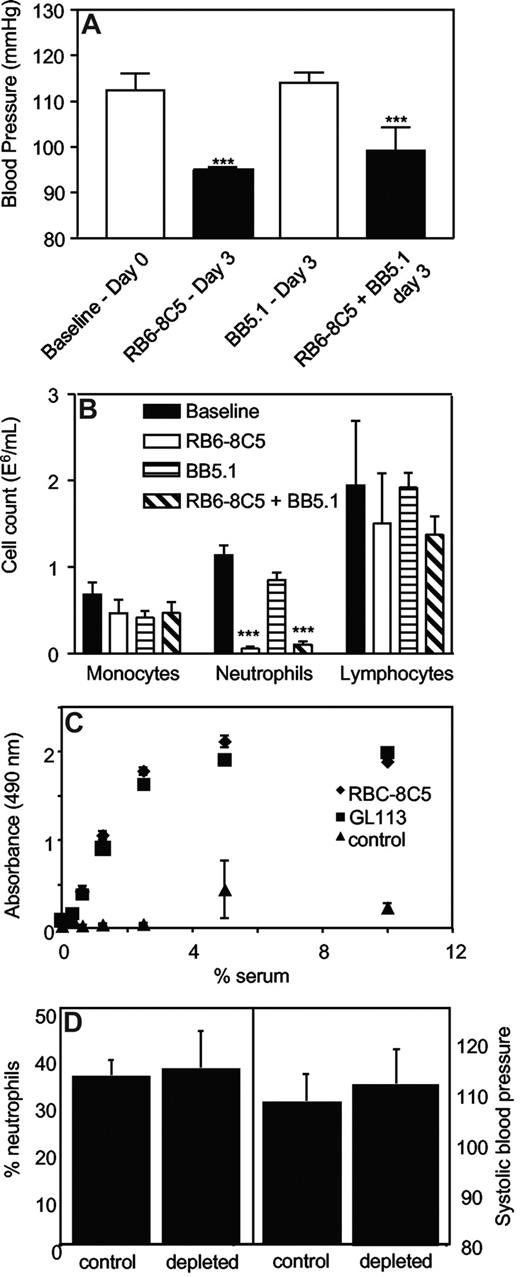

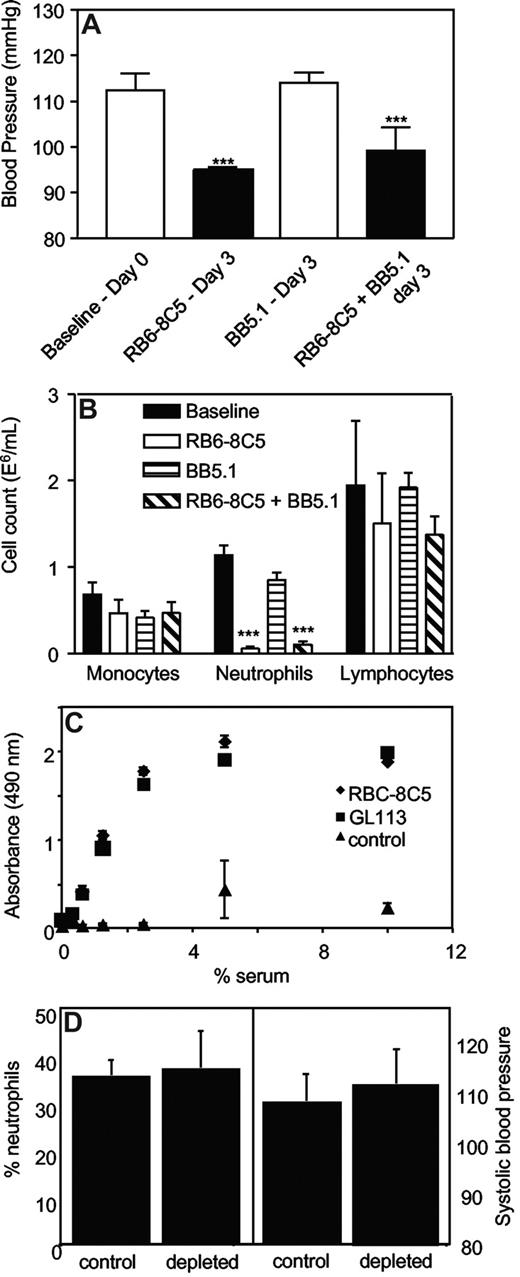

In vivo inhibition of complement C5 during neutrophil depletion.

Systolic BP was determined in mice administered anti-C5 Ab (BB5.1, 1 mg intraperitoneally), which blocks the common terminal pathways, during induction of neutropenia. BB5.1 alone (1 mg intraperitoneally) had no effect on systolic BP, nor did it prevent or enhance the hypotensive effect of RB6-8C5, or inhibit clearance of neutrophils (Figure 3A,B).

Complement C3 but not C5 is required for neutrophil depletion. (A) Inhibition of C5 does not prevent RB6-8C5–induced neutropenia. Blood pressures were measured daily by tail-cuff plethysmography following administration of RB6–8C5 with/without BB5.1 (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM) by intraperitoneal injection. ***P < .001 versus day 0 using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett posthoc test. (B) C5 inhibition does not prevent neutrophil depletion by RB6-8C5. Neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes were counted on day 3 after injection of RB6-8C5 with or without BB5.1, by differential counting of whole blood. (C) RB6-8C5 and GL113 activate complement in vitro to a comparable extent. Activation of mouse complement by 0.05 mg antibodies was determined by measuring C3 deposition from mouse serum, in antibody-coated wells, using an ELISA (n = 3, mean ± SEM). (D) C3 is required for neutrophil depletion and hypotension. RB6-8C5 was administered to C3−/− mice for 3 days; then neutrophil levels were determined using differential counting and blood pressure using tail-cuff plethysmography (n = 4-5, mean ± SEM).

Complement C3 but not C5 is required for neutrophil depletion. (A) Inhibition of C5 does not prevent RB6-8C5–induced neutropenia. Blood pressures were measured daily by tail-cuff plethysmography following administration of RB6–8C5 with/without BB5.1 (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM) by intraperitoneal injection. ***P < .001 versus day 0 using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett posthoc test. (B) C5 inhibition does not prevent neutrophil depletion by RB6-8C5. Neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes were counted on day 3 after injection of RB6-8C5 with or without BB5.1, by differential counting of whole blood. (C) RB6-8C5 and GL113 activate complement in vitro to a comparable extent. Activation of mouse complement by 0.05 mg antibodies was determined by measuring C3 deposition from mouse serum, in antibody-coated wells, using an ELISA (n = 3, mean ± SEM). (D) C3 is required for neutrophil depletion and hypotension. RB6-8C5 was administered to C3−/− mice for 3 days; then neutrophil levels were determined using differential counting and blood pressure using tail-cuff plethysmography (n = 4-5, mean ± SEM).

Direct activation of complement by antibodies.

The ability of both RB6-8C5 and the control antibody, GL113 to activate complement in vitro was compared by measuring C3 fragment deposition from mouse serum by immobilized mAbs. Complement was identically activated in a dose-dependent manner by either mAb (Figure 3C).

Examination of neutrophil depletion and blood pressure in C3−/− mice.

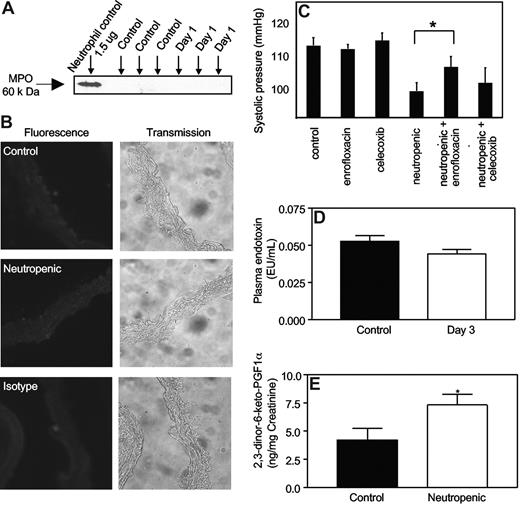

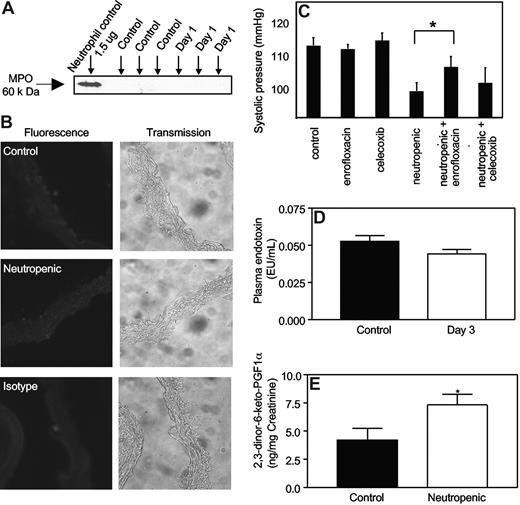

Examination of neutrophil activation and degranulation in the vasculature in vivo.

We examined for the presence of myeloperoxidase (MPO),which comprises approximately 5% of neutrophil protein, both in plasma and on the endothelium of aortic rings, where it is known to localize following neutrophil degranulation in vivo.6 Western blotting of plasma from neutropenic mice (day 1 after RB6-8C5) did not demonstrate MPO, and using immunohistochemistry, MPO was not observed on aortic endothelium (Figure 4A,B).

Neutrophil depletion by RB6-8C5 does not cause vascular MPO release into plasma, nor elevated plasma LPS, but neutropenic mice generate more prostacyclin in vivo. (A) Free MPO is not detected in plasma from neutropenic mice. Plasma from control and neutropenic mice (1 day after injection), or isolated leukocytes from healthy mice, were probed for MPO with rabbit polyclonal anti-MPO antibody (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA; 1:1000) and visualized using ECL (Amersham) followed by a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antirabbit secondary antibody (1:20 000). (B) MPO immunostaining is not detected during neutropenia. Aortic sections from control and neutropenic mice (day 1) were sectioned and immunostained for MPO. Representative sections are shown for each condition. (C) Hypotensive response to neutropenia is inhibited by antibiotic but not celecoxib. Mice were administered celecoxib (400 mg/kg/day) or enrofloxacin (0.4 g/L drinking water) for 3 days prior to induction of neutropenia, with blood pressure determined using tail-cuff pletysmography at day 3 (n = 5, mean ± SEM, P < .05, Student t test). (D) Plasma endotoxin is unchanged in neutropenic mice. Plasma endotoxin was measured in control and neutropenic mice using the LAL assay. (E) Neutropenic mice generate more prostacyclin in vivo. The prostacyclin metabolite 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α was quantified in mouse urine collected over a 24-hour period from control and neutropenic (days 2-3) using a sensitive and specific GC/MS technique (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM). *P < .05 versus control using one-tailed Student t test.

Neutrophil depletion by RB6-8C5 does not cause vascular MPO release into plasma, nor elevated plasma LPS, but neutropenic mice generate more prostacyclin in vivo. (A) Free MPO is not detected in plasma from neutropenic mice. Plasma from control and neutropenic mice (1 day after injection), or isolated leukocytes from healthy mice, were probed for MPO with rabbit polyclonal anti-MPO antibody (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA; 1:1000) and visualized using ECL (Amersham) followed by a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antirabbit secondary antibody (1:20 000). (B) MPO immunostaining is not detected during neutropenia. Aortic sections from control and neutropenic mice (day 1) were sectioned and immunostained for MPO. Representative sections are shown for each condition. (C) Hypotensive response to neutropenia is inhibited by antibiotic but not celecoxib. Mice were administered celecoxib (400 mg/kg/day) or enrofloxacin (0.4 g/L drinking water) for 3 days prior to induction of neutropenia, with blood pressure determined using tail-cuff pletysmography at day 3 (n = 5, mean ± SEM, P < .05, Student t test). (D) Plasma endotoxin is unchanged in neutropenic mice. Plasma endotoxin was measured in control and neutropenic mice using the LAL assay. (E) Neutropenic mice generate more prostacyclin in vivo. The prostacyclin metabolite 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α was quantified in mouse urine collected over a 24-hour period from control and neutropenic (days 2-3) using a sensitive and specific GC/MS technique (n ≥ 3, mean ± SEM). *P < .05 versus control using one-tailed Student t test.

Involvement of bacteria in mediating the hypotensive response to neutropenia

To examine the potential role of bacterial products, enrofloxacin (a fluoroquinoline antibiotic) was administered 3 days before and during induction of neutropenia. While this broad-spectrum antibiotic had no effect on basal blood pressure, there was a partial and significant inhibition of the neutropenia-induced fall in blood pressure (Figure 4C). Quantitation of endotoxin in plasma from healthy and neutropenic (day 3) mice revealed no differences (Figure 4D). This suggests other bacterial products are likely to be involved, for example, peptidoglycans and lipotechoic acids.

Mice exhibit an increase in 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α in urine during neutropenia

The potential role of COX-2–derived prostacyclin in mediating the fall in blood pressure was examined by administering celecoxib during induction of neutropenia. The dose used has been shown to inhibit systemic prostacyclin generation by more than 70%.25 There was no effect of celecoxib administration on blood pressure either before or during neutropenia induction (Figure 4C). Furthermore, examination of PE vasoconstriction by aortae in the presence of indomethacin or celecoxib failed to implicate COX-2 in the decreased PE vasoconstriction observed (not shown). However, neutropenia was associated with a significant elevation in systemic generation of prostacyclin as determined by measuring urinary excretion of its stable metabolite 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α (2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α) in mouse urine at days 0 and 3 (Figure 4E).

Discussion

Neutrophils are orchestrating cells of the innate immune system, circulating through the body and extravasating to sites of infection and injury where they perform important roles in host defense. While the mechanisms by which they migrate and activate are well characterized, whether their interaction(s) with the vasculature during normal circulation has functional consequences on blood vessel behavior has not been studied before. Herein, we uncovered a novel facet of neutrophil biology, namely the requirement of these cells for maintenance of normal vascular tone in otherwise healthy mice. Benign hereditary neutropenia is found in certain population groups, including Yemenites, Jews, black Bedouins, West Indians, and Arab Jordanians.26 In these groups, the neutropenia is usually mild, with only up to 50% decrease from normal range, and is not associated with increased risk of severe infection. However, Yemenites (with on average 25% lower neutrophil counts) have lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure than non-Yemenites with the difference being statistically significant for females (P < .05).27 The drop is smaller (3-5 mm Hg drop) than noted herein, although the extent of neutropenia in Yemenites is mild. Neutropenia in humans also occurs following chemotherapy (eg, in cancer). Hypotension occurs in this group in the context of fever and infection, however a small drop in blood pressure may be missed in the clinical setting in the absence of other symptoms.28

In our studies, neutropenia was induced by immunodepletion of Gr-1+ cells.17,23 The protocol resulted in a complete and selective removal of neutrophils within 24 hours that persisted for up to 7 days (Figure 1A,B). This model has been extensively used by others to study immune responses and behaves similarly to chemical neutropenia (eg, induced by vinblastine, cyclophosphamide or Gfi1 deficiency).29-31 The mechanism involves opsonization of antibody-coated cells with C3b, then their removal through the reticuloendothelial system, since C3−/− mice but not C5−/− mice were protected against RB6-8C5–induced neutropenia (Figure 3). There was no evidence of intravascular activation of neutrophils, since MPO was not found either in plasma or localized to vascular endothelium (Figure 4).

Hypotension occurred within 3 days of neutropenia, coinciding with an inability of the aorta to maintain tone in vitro (Figure 1C,D). fMLP-activated human neutrophils consume NO in vitro exclusively through NADPH oxidase, therefore inhibition of NO consumption through neutrophil depletion was considered.3 However, neutropenia was complete by day 1, while onset of hypotension was more gradual. This instead suggested a mechanism involving alterations in gene expression. Pharmacologic and genetic studies established that elevated NO generation was responsible and that this was generated exclusively via iNOS (Figures 1E-G, 2A-C). iNOS induction involved IFNγ, although elevations in mRNA for this cytokine were not found in aortic tissue of neutropenic mice (Figure 2D,E, and data not shown). This suggests that IFNγ signaling is not up-regulated via changes in its protein level. Alternatively, it may involve regulation of SOCS1 or PIAS1, proteins that inhibit by preventing IFNγ-mediated STAT1, signaling.

The effect of antibiotics indicated that bacterial products were involved, but not LPS since its plasma levels were unchanged (Figure 4C,D). Numerous other bacterial products can synergize with IFNγ to up-regulate iNOS via TLR receptors, including lipotechoic acid and peptidoglycans. While neutropenia in humans increases susceptibility to infection, the speed with which these vascular effects become apparent, in the absence of overt clinical symptoms, was notable. The mice were certified free from 11 viruses, 14 bacterial strains, 6 parasites, and various mycoplasma and fungi when obtained and were housed in a clean facility (routinely tested negative for 17 viruses, 3 parasites, and 15 bacterial strains) for approximately 2 weeks. The results reveal the critical role that neutrophils play in continuous suppression of infection, even in healthy “clean” animals. No reports exist regarding how soon humans with neutropenia experience subclinical infection. However, healthy Yemenites have elevated hsCRP and fibrinogen, suggesting that chronic low-grade inflammation due to infection occurs in humans with minor forms of neutropenia.27 In more severe neutropenia, for example associated with fever and leukemia in children, hypotension is one of the major predictive risk factors for an invasive bacterial infection.32 In our study, the origin of the bacteria is not known, however the gastrointestinal tract is a potential source. Patients with hematologic malignancies can develop neutropenic enterocolitis, and gut sterilization has been advocated as a treatment for preventing infection in granulocytopenic patients.33,34 Several other sites are also possible, including respiratory tract, urinary tract, skin, oral cavity, and ear.35

In a wound healing model, neutrophils exert an active anti-inflammatory action in vivo via inhibiting tissue TNFα and IL1β synthesis, through generation of an unknown factor of less than 3 kDa, but this factor has not been identified.23 In the light of our data, a role for bacteria stimulating inflammation in that study cannot be excluded. We looked for changes in lipid signaling mediators (< 3 kDa) that decrease blood pressure or inflammation. Neutropenic mice generated more prostacyclin in vivo (Figure 4E), however vascular tone was not restored using prostaglandin H synthase inhibitors in vitro or in vivo (Figure 4C and data not shown). Lipoxin A4 (LXA4), an anti-inflammatory lipid generated by neutrophils, was not detected in plasma of either control or neutropenic mice. Previous studies have reported levels of LXA4 of 5 ng/mL in murine plasma.36 This would be easily detected by our mass spectrometry method, which has a limit of quantitation for eicosanoids around 1 pg. The discrepancy may be due to use of ELISAs to measure LXA4, a technique known to be susceptible to overestimation, as recently described.37 We also measured TGFβ1, since inflammatory-challenged neutropenic mice generate less, and mice lacking this cytokine have elevated iNOS and IFNγ signaling in vivo.23,38 However, we did not detect changes in plasma TGFβ1 or aortic TGFβ1 mRNA in our model (not shown). While our study showed that the most likely effect of IFNγ was to alter iNOS expression and NO generation, it should be appreciated that this cytokine may exert additional influences that could contribute to altered vasoconstriction. These may include changes in IFNγ-regulated vessel wall expression of recently described NOX isoforms, altered mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, and alterations in NOS coupling.39-41

These studies indicate that neutrophils actively exert an anti-inflammatory effect in the vasculature in vivo, through blocking proinflammatory actions of bacteria. However, this may apply only to neutrophil counts below and up to normal, since elevated neutrophils have been independently associated with increased inflammation and atherosclerosis in a number of separate studies, as noted in Madjid et al42 and references therein. In that case, their proinflammatory action is likely due to direct effects of the neutrophils themselves, for example through mediating oxidative damage to the vascular wall. Up to now, studies designed to uncover roles of neutrophils in pathophysiology have focused on responses in inflammation models. Consequently, there is no information regarding how they might influence physiological processes in otherwise healthy animals, or how quickly inflammation may become apparent in their absence. This study shows that a constant surveillance of the vasculature by neutrophils is critical for eliminating low-grade bacterial infections and mechanistically helps to maintain the homeostatic regulation of vascular tone. The results provide insight into early changes that occur in neutropenic vessels and are relevant for our understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition in humans.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcus Coffey for expert technical advice.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (V.B.O., B.P.M., A.J.H.), National Institutes of Health GM15431, ES13125, and DK48831 (J.M.), Medical Research Council (A.G.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ku 961/8-2), and European Commission (FP6, LSHM-CT-2004-0050333) (H.K.).

National Institutes of Health

Wellcome Trust

Authorship

Contribution: J.M., B.C., K.W., J.D.M., E.S.T., P.B.A., B.P.M., V.D., H.K., and P.C. performed experiments; J.M., A.G., B.P.M., S.A.J., and V.B.O. designed experiments; A.J.H. contributed vital analytical tools; and J.M. and V.B.O. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Valerie B. O'Donnell, Dept of Medical Biochemistry & Immunology, Cardiff University, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4XN, United Kingdom; e-mail: o-donnellvb@cardiff.ac.uk.