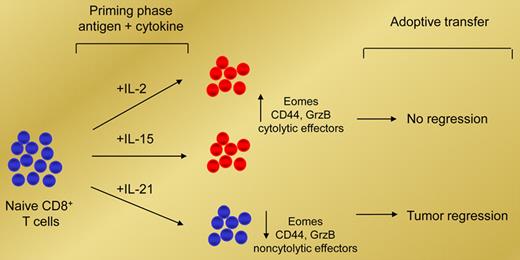

In this issue of Blood, Hinrichs and colleagues report that priming T cells with interleukin (IL)–21 can potently enhance their antitumor effects following adoptive transfer, whereas priming T cells with IL-2 impairs their antitumor function.

Over the past 2 decades, IL-2 has been commonly used to generate effector T cells for the adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Transfer of IL-2–activated, tumor-specific T cells has led to some remarkable cases of tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma.1 However, the use of IL-2 appears to be a double-edged sword. Although IL-2 can induce activation and proliferation of CD8+ T cells, it can also induce activation-induced cell death and is important for the development of T regulatory cells.2 Recent studies have revealed that the differentiation state of CD8+ T cells following transfer can affect their ability to mediate tumor rejection. Indeed, studies in patients have shown that persistence of transferred T cells and subsequent antitumor responses correlate well with cells being in a early state of effector T-cell differentiation.3 These results raise the intriguing possibility that the use of cytokines other than IL-2 that can repress differentiation of CD8+ T cells into cytolytic effector cells may lead to more profound antitumor responses.

In their article, Hinrichs and colleagues show that IL-2 and IL-21, which share the common cytokine receptor γ-chain, mediate opposing effects on antigen-induced CD8+ T-cell differentiation. The authors demonstrate that antigen-induced expression of Eomes, expression of IL-2Rα, and differentia-tion of naive CD8+ T cells into CD44+ granzyme B+ effector CD8+ T cells are promoted by both IL-2 and IL-15, but surprisingly, are suppressed by IL-21 (see figure). However, instead of inducing T-cell anergy, adoptive transfer studies reveal that IL-21–primed CD8+ T cells could undergo secondary expansion and induce effective tumor regression. In contrast, adoptive transfer of either IL-2–primed or IL-15–primed CD8+ T cells has little antitumor effect (see figure). Interestingly, the antitumor effects impaired by IL-2–primed CD8+ T cells were overcome by the addition of IL-21.

IL-2 and IL-21 mediate opposing effects on antigen-induced CD8+ T-cell differentiation. Priming naive CD8+ T cells with IL-2 or IL-15 promotes their cytolytic effector function but impairs their antitumor capability in vivo. In contrast, priming naive CD8+ T cells with IL-21 suppresses their cytolytic effector function but enhances their ability to mediate tumor regression in vivo.

IL-2 and IL-21 mediate opposing effects on antigen-induced CD8+ T-cell differentiation. Priming naive CD8+ T cells with IL-2 or IL-15 promotes their cytolytic effector function but impairs their antitumor capability in vivo. In contrast, priming naive CD8+ T cells with IL-21 suppresses their cytolytic effector function but enhances their ability to mediate tumor regression in vivo.

Through a series of elegant experiments using cDNA microarray, the authors reveal that IL-21 confers a distinct gene-expression program marked by increased expression of the adhesion molecule L-selectin. This mo-lecule plays an important role for transferred tumor-reactive T cells, as it mediates lymph-node trafficking and is characteristic of central memory T cells.4 In contrast to IL-21–primed T cells, the authors describe decreased expression of L-selectin on IL-2–primed and IL-15–primed CD8+ T cells following antigen restimulation, contributing to their lack of antitumor effect. Further mechanistic insight and a full understand-ing of how these differ-ent cytokine-primed T cells undergo or fail to undergo expansion following restimulation will be important in optimizing this approach for the treatment of cancer patients.

In conclusion, the above findings have important implications for developing more effective immunotherapies for cancer. However, several important questions remain. Can IL-21–primed T cells mediate enhanced tumor regression in other models, particularly against metastatic disease? Can IL-21–primed T cells generate an effective antitumor response against secondary challenge? It is becoming increasingly clear that understanding how different cytokines program CD8+ T cells will lead to maximizing the enormous potential of adoptively transferred T cells for cancer immunotherapy.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■