Abstract

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) protein LMP1 is considered to be a functional homologue of the CD40 receptor. However, in contrast to the latter, LMP1 is a constitutively active signaling molecule. To compare B cell–specific LMP1 and CD40 signaling in an unambiguous manner, we generated transgenic mice conditionally expressing a CD40/LMP1 fusion protein, which retained the LMP1 cytoplasmic tail but has lost the constitutive activity of LMP1 and needs to be activated by the CD40 ligand. We show that LMP1 signaling can completely substitute CD40 signaling in B cells, leading to normal B-cell development, activation, and immune responses including class-switch recombination, germinal center formation, and somatic hypermutation. In addition, the LMP1-signaling domain has a unique property in that it can induce class-switch recombination to IgG1 independent of cytokines. Thus, our data indicate that LMP1 has evolved to imitate T-helper cell function allowing activation, proliferation, and differentiation of EBV-infected B cells independent of T cells.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a γ-herpes virus that preferentially infects human B lymphocytes. It has adapted to persist in B cells by encoding proteins mimicking cellular proteins that play important roles in B-cell physiology.1 An example of the latter is the viral latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), which is considered to be a functional homologue of the CD40 receptor.2

CD40 is expressed on antigen-presenting cells including B cells, whereas the CD40 ligand (CD40L, CD154) is expressed mainly on activated T cells. The CD40 receptor belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family, containing an extracellular portion with 4 cysteine-rich domains that mediate ligand binding. CD40-CD40L interactions play a crucial role in the T cell–dependent (TD) immune response. CD40 and CD40L knockout mice show defects in the immunoglobulin (Ig) class-switch recombination (CSR), the formation of germinal centers (GCs), somatic hypermutation (SHM) of Ig genes, and the establishment of B-cell memory.3,4 In vitro stimulation of the CD40 receptor induces proliferation and activation of B cells, and mediates cytokine-dependent CSR.5

LMP1 shows several functional similarities with the CD40 receptor. Both triggering of the CD40 receptor and LMP1 expression lead to activation, proliferation, and survival of B cells.6 The intracellular domains of LMP1 and CD40 both interact with tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated factors (TRAFs) and activate overlapping signaling pathways, including extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38/MAPK, and NFκB.2 However, LMP1 and CD40 do not interact with exactly the same sets of molecules, indicating also some differences in their signaling properties.7-10 Thus, both LMP1 and CD40 interact directly with TRAFs 1, 2, 3, and 5, but only CD40, and not LMP1, binds directly to TRAF 6.7,11 Conversely, LMP1, but not CD40, binds to the tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated death domain protein (TRADD) and receptor-interacting protein (RIP).12 The most striking difference between LMP1 and CD40 is that LMP1 constitutively signals independently of ligand, mediated by self-aggregation through its 6 transmembrane-spanning domains.13 Therefore, it is difficult to directly compare the signaling properties of the 2 molecules. It was previously shown that B cell–specific expression of LMP1 in transgenic mice only partially reconstituted CD40 deficiency. LMP1 expression in CD40−/− mice could induce antibody class-switching to IgG1, but could not induce GC formation or the production of high-affinity antibodies after TD immunization.14 LMP1 expression even blocked GC formation in the presence of the endogenous CD40 receptor. However, it was also recently shown that constitutively active CD40 signaling in B cells, mediated by a fusion protein of the transmembrane domain of LMP1 and the signaling domain of CD40 (LMP1/CD40), blocks the GC reaction.15 Thus, it seems that the constitutive activation of B cells by either LMP1 or CD40 leads to a differentiation block that prevents GC formation.

To study LMP1 signaling independently from its constitutive activity and to compare it with CD40 receptor signaling, we fused the LMP1 signaling domain to the transmembrane- and ligand-binding domain of the CD40 receptor and generated a transgenic mouse strain expressing this CD40/LMP1 fusion protein upon Cre-mediated recombination. CD40/LMP1 expression was induced through a Cre transgene controlled by the CD19 locus16 to study the effects mediated by LMP1 signaling exclusively in B cells. We show here that LMP1 signaling in B cells completely substituted CD40 signaling without inducing hyperactivation and proliferation. Besides, the LMP1 signaling domain provided B cells with unique signals to induce cytokine-independent class-switch recombination to IgG1.

Methods

Generation of the transgenic mouse line CD40/LMP1

The CD40/LMP1 chimeric gene was generated by fusing the murine CD40 cDNA encoding for the first 215 amino acids (aa's) (amplified by reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] from murine splenic cell RNA using the primer 5′CD40: 5′-GAGCGTTTAAACTTGGCTCTTCTGATCTCGC-3′; 3′CD40: 5′-GAGACCATGGATATAGAGAAACACCCCG-3′) to the cDNA of LMP1 encoding for the terminal 200 aa's. To insert the CD40/LMP1 fusion gene into the Rosa26-locus the vector pRosa26-1 was used.17 Before introducing CD40/LMP1, pRosa26-1 was modified by introducing a loxP-flanked region, consisting of a stop cassette containing a transcription and translation termination site,18 the gene encoding the red fluorescent protein (not expressed in this context), and a neomycin-resistance gene flanked by frt sites. The CD40/LMP1 fusion gene was cloned downstream of the stop cassette. The final targeting vector was sequenced, linearized, and electroporated into Balb/c-derived embryonic stem (ES) cells. The targeted ES cells were screened for homologous recombination by Southern blot analysis and a subset was transfected with a Cre-expression vector (pGK-Cre-bpA, kindly provided by Kurt Fellenberg) to test Cre-loxP–mediated deletion of the stop cassette. The DNA was digested with EcoRI and hybridized with a specific radioactive labeled Rosa26-probe.17 Recombinant ES cells containing the loxP flanked region were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, which were then transferred into foster mothers to obtain chimeric mice.

Mice

Mice carrying the CD40/LMP1flSTOP allele were crossed to the CD19-Cre mouse strain (C57BL/6) to generate mice expressing the transgene only in B cells. Offspring of this crossing were bred to CD40−/− mice (Balb/c) to generate CD40/LMP1-expressing mice on a CD40-deficient background (CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/−). Mice were analyzed at 8 to 16 weeks of age. As controls, wt CD40+/+ and CD40−/− mice with or without CD19-Cre were used. The control mice were always on the same mixed background as CD40/LMP1-expressing mice. Mice were routinely screened by PCR using primers specific for CD40/LMP1 (5′CD40: 5′-TTGGCTCTTCTGATCTCGC-3′; 3′LMP1: 5′-CATCACTGTGTCGTTGTCCA-3′) and CD19-Cre.16 The B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ mouse strain expressing the leukocyte marker Ly5.1 was purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All mice were bred and maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions and the experiments were performed in compliance with the German animal welfare law and have been approved by the institutional committee on animal experimentation.

Mouse immunizations

Eight- to 12-week-old mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 μg alum-precipitated nitrophenylacetyl chicken gamma globulin (NP-CGG; Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA).

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Single-cell suspensions prepared from various lymphoid organs were surface stained with fluorescent-labeled mAbs including anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD5 (53-7.3), anti-CD21 (7G6), anti-CD23 (B3B4), anti-CD40 (3/23), anti-CD80 (16-10A1), anti-CD95 (Jo2), anti-IgD (11-26c.2a), anti-IgG1 (A85-1), anti-IgM (R6-60.2), and anti-Ly5.2(104) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). PNA-FITC was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA); anti-CD11c from, Miltenyi-Biotech (Auburn, CA). All analyses were performed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), and results were analyzed using CELLQuest software (BD Biosciences). Cell sorting was performed on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences).

In vitro B-cell cultures

After red blood cell lysis, splenic IgG1-negative B cells were negatively selected using CD43 and IgG1 magnetic beads (Miltenyi-Biotech). Cells were cultured in B-cell medium for 5 days in 96-well plates (5 × 105/200 μL per well). Stimuli added to the cultures included anti-CD40 antibody (2.5 μg/mL, clone 1C10; Biolegend, San Diego, CA), IL4 (60 ng/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and anti-IL4 (15 μg/mL; kindly provided by Elisabeth Kremmer, GSF Munich). For CFSE labeling, B cells were incubated in serum-free RPMI media containing 5-(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester (CFDA SE = CFSE; final concentration: 5 μM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 10 minutes at 37°C. For mixed B-cell cultures, Ly5.1-expressing B cells were cultured 1:1 together with B cells of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice expressing Ly5.2.

Immunoblotting

CD43-depleted B cells were preincubated for 1 hour at 37°C before anti-CD40 antibody (2.5 μg/mL, clone 1C10; Biolegend) was added to the medium for 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes. Cells were lysed in 2 × NP-40 lysis buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 7,4, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA, 2% NP-40) including protease inhibitors (Complete Mini; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitors (Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail; Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein extracts were separated on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Membranes were immunoblotted with anti–phospho-JNK1/2 (T183/Y185), anti–phospho-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204), anti–phospho-p38/MAPK (T180/Y182), anti–phospho-IκB-α (S32/36), anti-JNK1/2, anti-ERK1/2, anti-p38/MAPK, and anti–IκB-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Spleens were embedded in OCT Tissue-Tek (Sakura, Zoeterwoude, the Netherlands), frozen on dry ice, and cut with 8-μm thickness. The sections were thawed, air dried, fixed in acetone, incubated with avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories), and stained with peroxidase conjugated anti–mouse IgM (Sigma, St Louis, MO), rat antimouse CD3 (kindly provided by Elisabeth Kremmer, GSF Munich), or biotin-conjugated PNA (Vector Laboratories). Anti-CD3 antibody was detected using biotin conjugated mouse anti–rat IgG1 (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Biotinylated reagents were detected using SA-AP (Sigma). Enzyme reactions were developed with alkaline phosphate or peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). Slides were analyzed with an Axiovert 135 (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) microscope with a PL 10×/20 eyepiece and a 5×/0.15 Plan-Neofluar objective lens (Zeiss); pictures were obtained with a RS Photometrics digital camera (Tucson, AZ) and processed with Openlab from Improvision (Coventry, United Kingdom) and Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

To determine Ig isotype concentrations and NP-specific antibodies, microtiter plates (Nunc, Rochester, NY) were coated with Ig-specific rat antimouse antibodies (IgM, II/41; IgG1, A85-3; IgG2a, R11-8; IgG2b, R9-91; IgG3, R2-38; IgA, C11-3; BD Biosciences); or with NP3-BSA or NP17-BSA (Biosearch Technologies), in 0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer (pH 9.2) at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, wells were blocked with PBS, 1% milk powder at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes. Serially diluted serum samples were applied to the wells and incubated for 1 hour at RT, then incubated 30 minutes at RT with biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies specific for the different isotypes (IgM, R6-60.2; IgG1, A85-1; IgG2a, R19-15; IgG2b, R12-3; IgG3, R40-82; IgA, C10-1; BD Biosciences), followed by the incubation with streptavidin-coupled alkaline phosphatase at RT for 30 minutes. The amount of bound AP was detected by incubation with O-phenyldimine (Sigma) in 0.1 M citric acid buffer containing 0.015% H2O2. Following each incubation step, plates were washed 3 times with PBS. The OD at 405 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Photometer Sunrise RC; Tecan, Maennedorf, Switzerland), and antibody concentrations were determined by comparison with isotype-specific standards (IgM, G155-228; IgG1, MOPC-31C; IgG2a, G155-178; IgG2b, MPC-11; IgG3, A112-3; M18-254; BD Biosciences).

IgH somatic mutation analysis

Fourteen days after immunization with 100 μg NP-CGG, IgH rearrangements from sorted B-cell subsets (GC: B220+CD95+PNA+PI−; non-GC: B220+CD95−PNA−PI−) were PCR-amplified using the Expand High fidelity PCR system (Roche) and primer J558Fr3, which anneals in the framework 3 region of most VHJ558 genes, and primer JHCHint, which hybridizes in the intron 3′ of exon JH4.19 The 600-bp PCR product bearing the JH4 segment of the IgH was cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and sequenced. A stretch of 500-bp intron sequence immediately downstream of the JH4 element was analyzed for somatic mutations using SeqMan software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI).

Results

Generation of a transgenic mouse line expressing a conditional CD40/LMP1 transgene

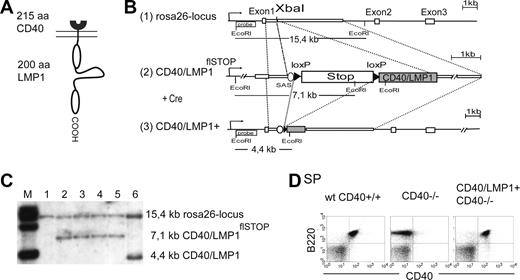

To study LMP1 signaling in vivo, we generated a transgenic mouse strain conditionally expressing a fusion protein of the ligand-binding and transmembrane domains of CD40 (amino acids [aa's] 1-215) and the cytoplasmic tail of LMP1 (aa's 186-386) (CD40/LMP1) (Figure 1A). A single copy of the chimeric gene was inserted into the murine Rosa26-genomic locus by homologous recombination in Balb/c-derived embryonic stem (ES) cells (Figure 1B). To restrict expression of CD40/LMP1 to specific cell types, a loxP-flanked transcription and translation termination site (stop cassette)18 was inserted upstream of the CD40/LMP1 coding sequence (CD40/LMP1flSTOP). After excision of the stop cassette by Cre-recombinase, the CD40/LMP1 transgene is placed under the transcriptional control of the ubiquitously active Rosa26-promoter. Correctly targeted ES cell clones were identified by Southern blot analysis (Figure 1C) and used to transmit the CD40/LMP1flSTOP allele into the mouse germ line on the Balb/c genetic background.

Generation of a transgenic mouse line conditionally expressing CD40/LMP1. (A) Schematic representation of the chimeric protein CD40/LMP1. The N-terminal 215 amino acids (aa's) of CD40 (receptor binding and transmembrane domain) were fused to the COOH-terminal 200 aa's of LMP1 (cytoplasmic domain). (B) Targeting strategy for the insertion of a conditional CD40/LMP1 allele (CD40/LMP1flSTOP) into the mouse Rosa26-locus. The figure shows (1) the wild-type Rosa26-locus with its 3 exons and the XbaI restriction site in the first intron where the transgene was inserted (2); the Rosa26-locus after homologous recombination of the targeting construct (CD40/LMP1flSTOP); and (3) the Rosa26-locus after homologous recombination and deletion of the stop cassette upon Cre-mediated recombination, which leads to the expression of CD40/LMP1 under transcriptional control of the endogenous Rosa26-promoter. The EcoRI recognition sites and the location of the probe for the Southern blot analysis are shown. The expected fragments after EcoRI digestion and hybridization with the labeled probe are indicated. Cre indicates Cre recombinase; SAS, splice acceptor site; and loxP, locus of crossing over in bacteriophage P1. (C) Southern blot analysis showing the different alleles after targeting and Cre-mediated recombination of the stop cassette in ES cells. The DNA was digested by EcoRI and hybridized with the labeled probe specific for the Rosa26-locus as shown in panel B. Lane 1 shows wild-type ES cells; lanes 2 to 5, ES cell clones showing correct targeting; and lane 6, ES cell clone with correct targeting after Cre-mediated deletion of the stop cassette. (D) B cell–specific CD40/LMP1 expression. Flow cytometry of splenic cells, gated for living cells (PI negative) and stained with anti-B220 and anti-CD40 antibodies. The anti-CD40 antibody binds to the extracellular portion of CD40 and recognizes both the CD40 receptor and CD40/LMP1. Virtually all B220+ B cells in the spleens of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice express CD40/LMP1.

Generation of a transgenic mouse line conditionally expressing CD40/LMP1. (A) Schematic representation of the chimeric protein CD40/LMP1. The N-terminal 215 amino acids (aa's) of CD40 (receptor binding and transmembrane domain) were fused to the COOH-terminal 200 aa's of LMP1 (cytoplasmic domain). (B) Targeting strategy for the insertion of a conditional CD40/LMP1 allele (CD40/LMP1flSTOP) into the mouse Rosa26-locus. The figure shows (1) the wild-type Rosa26-locus with its 3 exons and the XbaI restriction site in the first intron where the transgene was inserted (2); the Rosa26-locus after homologous recombination of the targeting construct (CD40/LMP1flSTOP); and (3) the Rosa26-locus after homologous recombination and deletion of the stop cassette upon Cre-mediated recombination, which leads to the expression of CD40/LMP1 under transcriptional control of the endogenous Rosa26-promoter. The EcoRI recognition sites and the location of the probe for the Southern blot analysis are shown. The expected fragments after EcoRI digestion and hybridization with the labeled probe are indicated. Cre indicates Cre recombinase; SAS, splice acceptor site; and loxP, locus of crossing over in bacteriophage P1. (C) Southern blot analysis showing the different alleles after targeting and Cre-mediated recombination of the stop cassette in ES cells. The DNA was digested by EcoRI and hybridized with the labeled probe specific for the Rosa26-locus as shown in panel B. Lane 1 shows wild-type ES cells; lanes 2 to 5, ES cell clones showing correct targeting; and lane 6, ES cell clone with correct targeting after Cre-mediated deletion of the stop cassette. (D) B cell–specific CD40/LMP1 expression. Flow cytometry of splenic cells, gated for living cells (PI negative) and stained with anti-B220 and anti-CD40 antibodies. The anti-CD40 antibody binds to the extracellular portion of CD40 and recognizes both the CD40 receptor and CD40/LMP1. Virtually all B220+ B cells in the spleens of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice express CD40/LMP1.

B-cell–specific expression of the CD40/LMP1 transgene on a CD40−/− background

CD40/LMP1flSTOP mice were crossed to the CD19-Cre mouse strain on the C57/BL6 genetic background to activate expression of the chimeric protein specifically in B cells.16 For simplicity, mice carrying the CD40/LMP1 knockin and the CD19-Cre alleles will be referred to as CD40/LMP1+ mice. As controls, wt//CD40+/+ and CD19-Cre+/−//CD40+/+ mice on the same mixed background as the CD40/LMP1+ mice were used, and will be referred to as wt CD40+/+. Unimmunized and immunized F1 CD40/LMP1+ mice on a CD40+/+ background were analyzed for their B-cell compartments and did not show any differences with control mice, indicating that CD40/LMP1 expression in B cells does not have any negative influence on the development and differentiation of B cells (Figure S1A-C, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). To analyze whether CD40/LMP1 is able to substitute for CD40 in vivo, mice were bred to CD40-deficient mice, which were on the Balb/c genetic background. Wt//CD40+/+ and CD19-Cre+/−//CD40+/+ mice were also backcrossed to Balb/c mice to obtain the same background of control and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice. FACS analyses of bone marrow and peripheral lymphoid organ cells showed that approximately 17% of B220+ B cells in the bone marrow (BM) and more than 95% of B220+ B cells in the periphery of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice stained positive for CD40 and therefore expressed the transgene (Figure 1D and data not shown). Bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BM-DCs) did not show CD40/LMP1 expression (Figure S2A,B). However, approximately 1% of B220− cells in the bone marrow showed expression of CD40/LMP1. Some of these cells expressed Gr-1, indicating that they belonged to the myeloid lineage (Figure S2C).

The lymphoid compartments of 8- to 16-week-old CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice were analyzed and compared with age-matched wt CD40+/+ and CD40−/− control mice. CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice showed normal weight and size of spleen and lymph nodes (data not shown). Immunohistochemical analyses of the spleens revealed that the structure of the follicles with the B- and T-cell zone was normal in the transgenic animals (Figure S3A). The percentages and total numbers of B220+ B and CD5high T cells in SP and inguinal lymph nodes (iLNs) were comparable in all 3 groups of mice analyzed (Figure 2A). The percentages of mature IgM+IgD+ B cells in all lymphoid organs and the percentages of CD21+CD23+ follicular (FO) and CD21highCD23low marginal zone (MZ) B cells in the spleen were normal in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice (Figure S3B,C).

CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice show normal B- and T-cell distribution and normal serum immunoglobulin titers. (A) Total numbers and percentages of B220+ B and CD5high T cells in both the spleen (SP) and inguinal lymph nodes (iLNs). Data presented are means (± SEM) of 4 to 5 mice per group tested in independent experiments. (B) Nonimmunized mice (5 per group) were analyzed for the concentrations of the total serum immunoglobulin titers of the indicated isotypes by ELISA. CD40−/− mice showed a defect in CSR to IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b, which could be rescued in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice.

CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice show normal B- and T-cell distribution and normal serum immunoglobulin titers. (A) Total numbers and percentages of B220+ B and CD5high T cells in both the spleen (SP) and inguinal lymph nodes (iLNs). Data presented are means (± SEM) of 4 to 5 mice per group tested in independent experiments. (B) Nonimmunized mice (5 per group) were analyzed for the concentrations of the total serum immunoglobulin titers of the indicated isotypes by ELISA. CD40−/− mice showed a defect in CSR to IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b, which could be rescued in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice.

To study whether CD40/LMP1 can substitute for CD40 in Ig class-switch recombination, serum Ig titers of unimmunized wt CD40+/+, CD40−/−, and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice were analyzed by ELISA. Whereas CD40−/− mice had decreased levels of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b in the serum, CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice had similar or even higher titers of these isotypes compared with wild-type mice. IgM levels were slightly elevated in the CD40−/− but not the CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice (Figure 2B). These results suggest that CD40/LMP1 can replace CD40 in the control of class-switch recombination in vivo.

LMP1 signaling rescues germinal center formation and high-affinity antibody generation in CD40−/− mice

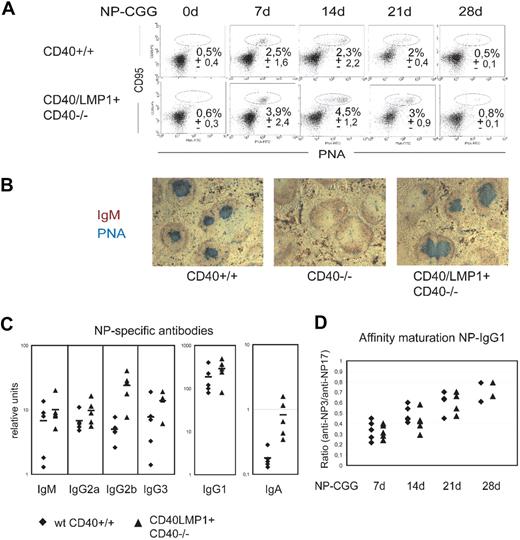

To investigate whether CD40/LMP1 can provide the B cells with the essential signals for germinal center (GC) formation, isotype switching, and affinity maturation in the absence of CD40, we immunized mutant and control mice with the hapten nitrophenylacetyl conjugated to chicken-gammaglobulin (NP-CGG). The presence of splenic GCs was revealed 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after immunization by flow cytometric and immunohistochemical analyses after staining with peanut agglutinin (PNA), which is specific for germinal center B cells. PNA-stained cells could be observed in immunized wt CD40+/+ and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice, but not in immunized CD40−/− mice. In unimmunized mice including CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice, GC and GC B cells could not be detected (Figure 3A,B). Immunohistochemical analyses of the spleens revealed that CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice showed a normal architecture of the follicles with the GC and mantle zone after immunization. Compared with controls, the transgenic animals on average showed a 2-fold increase of GC B- and plasma cell percentages upon immunization (Figure 3A and data not shown). However, CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− GC B cells did not show a higher proliferation rate, as measured by in vivo BrdU assays (Figure 4).

LMP1 signaling substitutes CD40 in germinal center formation and production of class-switched and high-affinity antibodies. (A) Flow cytometry to identify germinal center (GC) B cells (CD95+PNAhigh) in the spleens of wt CD40+/+ and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice at the indicated days after immunization with 100 μg NP-CGG. Cells are gated on B220+; numbers indicate the mean percentages (± SEM) of GC B cells of 2 to 5 mice analyzed per group. (B) Immunohistologic analysis of GC in the spleen, 14 days after immunization with 100 μg NP-CGG. Cryosections were stained with anti-IgM specific for B cells (red) and PNA specific for germinal center B cells (blue). Original magnification, ×50. (C) NP-specific antibody response 14 days after immunization with 100 μg NP-CGG. NP-specific immunoglobulin concentrations for the indicated isotypes were analyzed for 5 mice from both wt CD40+/+ (♦) and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− (▲). (D) Affinity maturation of NP-specific IgG1 antibodies at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. The ratio of antibody binding to low-density hapten (NP3-BSA) versus high-density hapten (NP17-BSA) is plotted for 2 to 5 mice per group.

LMP1 signaling substitutes CD40 in germinal center formation and production of class-switched and high-affinity antibodies. (A) Flow cytometry to identify germinal center (GC) B cells (CD95+PNAhigh) in the spleens of wt CD40+/+ and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice at the indicated days after immunization with 100 μg NP-CGG. Cells are gated on B220+; numbers indicate the mean percentages (± SEM) of GC B cells of 2 to 5 mice analyzed per group. (B) Immunohistologic analysis of GC in the spleen, 14 days after immunization with 100 μg NP-CGG. Cryosections were stained with anti-IgM specific for B cells (red) and PNA specific for germinal center B cells (blue). Original magnification, ×50. (C) NP-specific antibody response 14 days after immunization with 100 μg NP-CGG. NP-specific immunoglobulin concentrations for the indicated isotypes were analyzed for 5 mice from both wt CD40+/+ (♦) and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− (▲). (D) Affinity maturation of NP-specific IgG1 antibodies at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. The ratio of antibody binding to low-density hapten (NP3-BSA) versus high-density hapten (NP17-BSA) is plotted for 2 to 5 mice per group.

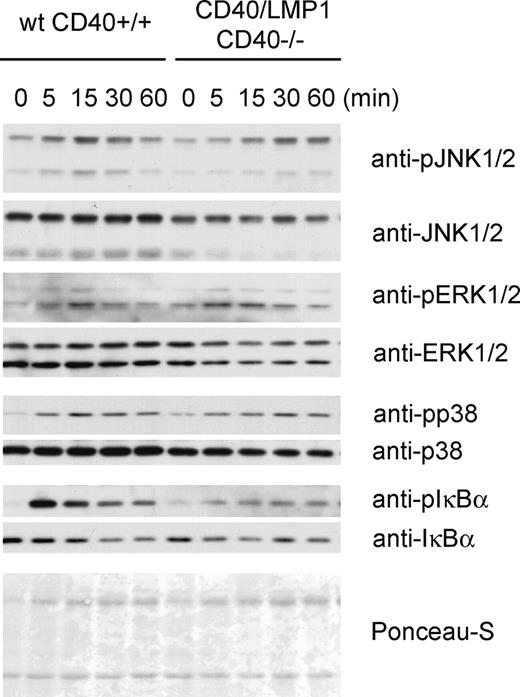

Activation of MAP-kinases and NFκB in wt CD40+/+ and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells. Immunoblotting for the activation of the MAPKs and NFκB after stimulation with agonistic anti-CD40 antibody. Splenic B cells were isolated by CD43 depletion and stimulated with anti-CD40 for the indicated times. Whole-cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Ponceau-S staining is shown as a loading control.

Activation of MAP-kinases and NFκB in wt CD40+/+ and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells. Immunoblotting for the activation of the MAPKs and NFκB after stimulation with agonistic anti-CD40 antibody. Splenic B cells were isolated by CD43 depletion and stimulated with anti-CD40 for the indicated times. Whole-cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Ponceau-S staining is shown as a loading control.

CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice were able to produce NP-specific antibodies of all isotypes analyzed (Figure 3C). In comparison with wt CD40+/+ controls CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice showed an increase of NP-specific antibodies, which is in line with the increased plasma cell population.

An important feature of a proper germinal center reaction is the development of Ig affinity maturation. By ELISA, NP-specific antibodies can be tested to show high or low affinity for NP by binding to low-density hapten and high-density hapten, respectively. To analyze Ig affinity maturation in immunized CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− and wt CD40+/+ mice, the concentrations of NP-specific IgG+ antibodies were analyzed 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after immunization. The ratio of anti-NP3/anti-NP17 binding of the antibodies increased with time similarly in both groups of mice (Figure 3D). In addition, we analyzed the Ig sequences of the intronic region downstream of JH4 for somatic hypermutation (SHM) 14 days after immunization. Whereas non-GC B cells of both CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− and wt CD40+/+ mice were devoid of somatic mutations, GC B cells of both groups showed approximately the same frequencies of SHM (0.53% vs 0.52%; Table 1). These results indicate that CD40/LMP1 expression in B cells can rescue GC formation and the generation of high-affinity antibodies upon TD immunization in CD40 deficient mice, but does not induce spontaneous GC formation.

The activation of MAP-kinases and NFκB in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells

To compare the signaling capacity of the CD40/LMP1-fusion protein and the endogenous CD40, we stimulated ex vivo isolated B cells for different time points with an agonistic anti-CD40 antibody. Western blot analyses indicated that CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells responded to anti-CD40 stimulation by phosphorylation of the MAP-kinases JNK, ERK, and p38, and by activation of the canonical NFκB pathway indicated by phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα (Figure 4). However, the JNK activation was delayed and the IκBα phosphorylation weak, suggesting that compared with CD40 the cytoplasmic tail of LMP1 in our system results in a normal or slightly dampened—rather than an enhanced—signaling.

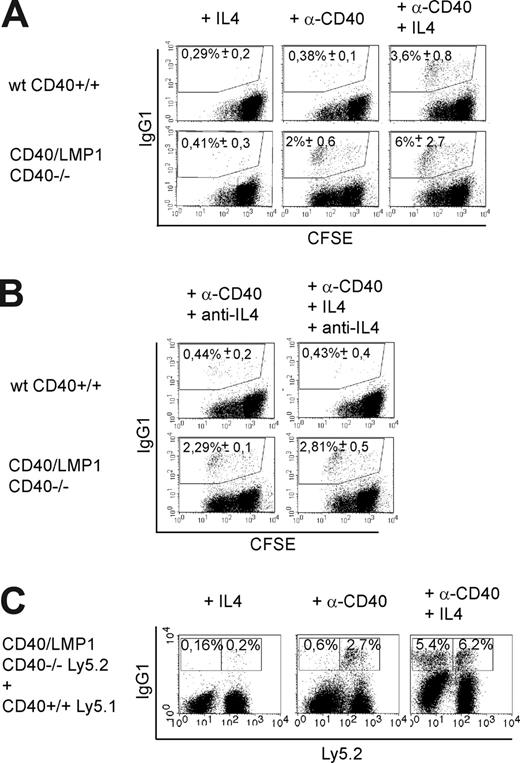

LMP1 signaling induces cytokine-independent class-switch recombination to IgG1

It has been reported previously that LMP1 is able to induce class-switch recombination in a Burkitt lymphoma cell line in vitro, but a possible role of cytokines in this process has not been elucidated.20 To test whether the LMP1 signaling domain is able to induce class-switch recombination in primary B cells independent of cytokines, isolated splenic IgG1-negative B cells were labeled with CFSE and cultured in the presence of agonistic CD40 antibody (anti-CD40), IL4, anti-CD40 plus IL4, or without any stimulus, and stained for surface IgG1 on day 5 (Figure 5A). In cultures of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells, a distinct fraction of IgG1 class-switched cells could be detected upon stimulation with anti-CD40 only. The latter subset was absent in cultures of anti-CD40–stimulated wt CD40+/+ B cells and appeared only after costimulation with anti-CD40 and IL4. CFSE labeling showed that CSR to IgG1 in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells did not correlate with a higher proliferation rate of these cells (Figure S5A). To study if transcription of the sterile Igγ1-locus is increased in anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells, quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed. In contrast to wt CD40+/+, CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells showed, after only 24 and 48 hours of anti-CD40 stimulation, a more than 2-fold induction of the γ1 sterile transcript, a prerequisite for CSR to IgG1 (Figure S5B).

LMP1 signaling induces cytokine-independent class-switch recombination to IgG1. (A,B) CD43- and IgG1-depleted splenic B cells were labeled with CFSE and cultured in the presence of the indicated stimuli for 5 days. Cells are gated on living (PI−) cells. Numbers indicate means of percentages plus or minus SEM of IgG1+ cells of 4 independent experiments. (A) CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells showed CSR to IgG1 after stimulation with agonistic anti-CD40 antibody (α-CD40) only, whereas in wt CD40+/+ B cells CSR was dependent on IL4. (B) Anti-IL4 antibody (15 μg/mL) was added daily to the cultures. The percentages of IgG1-positive cells were not affected in anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells, whereas CSR was inhibited by anti-IL4 antibody in wt CD40+/+ B cells stimulated with anti-CD40 and IL4. (C) Mixed B-cell cultures. IgG1-negative B cells of Ly5.1+ CD40+/+ and Ly5.2+ CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice were isolated by depletion of CD43+ and IgG1+ cells and cocultured in a 1:1 ratio for 5 days with the indicated stimuli. Treatment with anti-CD40 antibody induced CSR in only Ly5.2+ CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/−, but not in Ly5.1+ CD40+/+, B cells. In contrast, stimulation with anti-CD40 and IL4 led to equal amounts of IgG1+ B cells in both cell types. This indicates that CSR of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells reflects an intrinsic effect of the LMP1 signaling domain and not an increased release of cytokines. Numbers indicate means of percentages of IgG1+ cells of 3 independent experiments. Further evidence that LMP1 signaling induces cytokine-independent CSR to IgG1 is given in Figure S5.

LMP1 signaling induces cytokine-independent class-switch recombination to IgG1. (A,B) CD43- and IgG1-depleted splenic B cells were labeled with CFSE and cultured in the presence of the indicated stimuli for 5 days. Cells are gated on living (PI−) cells. Numbers indicate means of percentages plus or minus SEM of IgG1+ cells of 4 independent experiments. (A) CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells showed CSR to IgG1 after stimulation with agonistic anti-CD40 antibody (α-CD40) only, whereas in wt CD40+/+ B cells CSR was dependent on IL4. (B) Anti-IL4 antibody (15 μg/mL) was added daily to the cultures. The percentages of IgG1-positive cells were not affected in anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells, whereas CSR was inhibited by anti-IL4 antibody in wt CD40+/+ B cells stimulated with anti-CD40 and IL4. (C) Mixed B-cell cultures. IgG1-negative B cells of Ly5.1+ CD40+/+ and Ly5.2+ CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice were isolated by depletion of CD43+ and IgG1+ cells and cocultured in a 1:1 ratio for 5 days with the indicated stimuli. Treatment with anti-CD40 antibody induced CSR in only Ly5.2+ CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/−, but not in Ly5.1+ CD40+/+, B cells. In contrast, stimulation with anti-CD40 and IL4 led to equal amounts of IgG1+ B cells in both cell types. This indicates that CSR of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells reflects an intrinsic effect of the LMP1 signaling domain and not an increased release of cytokines. Numbers indicate means of percentages of IgG1+ cells of 3 independent experiments. Further evidence that LMP1 signaling induces cytokine-independent CSR to IgG1 is given in Figure S5.

Next we asked whether the CSR of anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells was mediated by an intrinsic effect of LMP1 signaling or by a paracrine mechanism of elevated cytokine release by these cells. To exclude that anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells synthesize IL4, leading in combination with anti-CD40 to CSR, we treated the cells with anti-IL4 antibody. Whereas the percentages of IgG1-positive cells were not affected in anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells, the CSR process was abrogated in wt CD40+/+ B cells stimulated with anti-CD40 and IL4, showing that the CSR induced in anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells is IL4 independent (Figure 5B). To further rule out that the CSR was induced by elevated cytokine release of CD40/LMP1-expressing B cells, we tested anti-CD40–stimulated cells for the transcription of several cytokine genes known to contribute to the induction of CSR to IgG1, such as IL4, IL13, IL21, BAFF, and APRIL. Neither CD40-stimulated wt CD40+/+ nor CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells showed detectable transcript levels of the indicated cytokines (Figure S5C). Finally, we performed mixed B-cell culture experiments. CD40+/+ B cells expressing the Ly5.1 leukocyte marker were cultured together with CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells expressing Ly5.2, and stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody, which induced CSR in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− but not in CD40+/+ B cells (Figure 5C).

These data indicate a unique intrinsic feature of the LMP1 signaling domain to induce cytokine-independent CSR to IgG1.

Discussion

The Epstein-Barr virus protein LMP1 and the cellular receptor CD40 are considered to be functional homologues. Evidence for similar effects on B-cell biology was based mainly on cell culture experiments, although recently several transgenic mice expressing LMP1 and fusion proteins of LMP1 and CD40 were reported.14,15,21 However, these studies were not conclusive enough. In CD40-deficient mice, LMP1 could restore the CD40 function only partially, rescuing class-switch recombination to IgG1 but not the germinal center formation. Moreover, mice on a CD40-proficient background expressing LMP1 or a LMP1/CD40 fusion protein mimicking a constitutive active CD40 molecule were hampered in germinal center formation, indicating that this phenotype is due to the constitutive activity of LMP1 and not to the signaling domains. A previous study published by Stunz et al of mice expressing a fusion protein of the extracellular and transmembrane region of CD40 and the cytoplasmic domain of LMP1 did not completely resolve the issue of functional homology of LMP1 and CD40 in B cells either, since the transgene was expressed under control of the MHC class II Eα promoter, allowing expression not only in B lymphocytes but in all antigen-presenting cells, including macrophages and bone marrow–derived dendritic cells.21 Those mice showed splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, spontaneous germinal center formation, disordered lymphoid architecture, and elevated IL6 and autoantibodies in the serum, suggesting that the cytoplasmic tail of LMP1 induces hyperactivation of B cells and disruption of the lymphoid architecture.

Here we show that when LMP1 signaling is restricted to B cells, it perfectly substitutes for CD40 signaling in those cells in vivo. B cell–specific expression of CD40/LMP1 was achieved upon deletion of an upstream loxP flanked stop cassette by Cre-recombinase expressed under control of the CD19 promoter.16 We could show that more than 95% of B cells in the periphery expressed CD40/LMP1. Only 1% of B220−/Gr-1+ cells expressed the transgene, which could reflect rare myeloid populations that either express CD19 or originate from CD19+ progenitor cells.22,23 We could not detect CD40/LMP1 expression in bone marrow–derived dendritic cells.

The lymphoid compartment of CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice was comparable with that of wt mice, showing normal B- and T-cell numbers and ratios, B-cell subset percentages, and lymphoid organ architecture. Unimmunized transgenic mice did not show spontaneous GC formation, nor signs of autoimmunity, such as expansion or hyperactivation of immune cells or autoantibodies in the serum (data not shown), suggesting that the abnormality of the immune system observed in the study of Stunz et al21 was due to CD40/LMP1 expression in non-B cells. Our data indicate a striking functional homology of the LMP1 and CD40 signaling domains. Upon TD immunization, LMP1 signaling provided the B cells with all essential signals for GC formation, isotype switching, SHM, and affinity maturation in the absence of CD40, and mediated an optimal organization of the follicles with GC and mantle zone. The only difference compared with wt was that CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice displayed an approximately 2-fold increase in the percentages of GC B and plasma cells and elevated Ig titers after TD immunization. The increase in GC B and plasma cells seems to be caused neither by more intense proliferation nor better survival of CD40/LMP1-expressing GC B cells. In vivo BrdU assays indicated similar fractions of proliferating GC cells in wt CD40+/+ and CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice. Regarding cell survival, ex vivo isolated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− and wt B cells showed the same percentages of living (PI negative) cells while keeping the cells in culture for 5 days (data not shown) suggesting a similar survival rate. This is in accordance with our observation that CD40/LMP1-expressing GC B cells show similar frequencies of somatic mutations in their rearranged heavy chain variable region gene segments as wt CD40+/+ B cells, since GC B cells with a survival advantage would be expected to undergo more rounds of division and therefore acquire more mutations in their Ig genes. Therefore, the increase of GC B-cell percentages in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− mice is most likely due to an increased recruitment of B cells into the GC. The reason for this could be either a specific effect of the LMP1 signaling domain or the slightly higher expression level of CD40/LMP1 compared with the endogenous CD40.

Beside its ability to perfectly substitute CD40 in vivo, the LMP1 signaling domain seems to have a unique property, namely to stimulate cytokine-independent CSR. Thus, a fraction of CD40/LMP1-expressing B cells stimulated in vitro with the agonistic anti-CD40 antibody 1C10 mediated CSR to IgG1, whereas CD40+/+ control B cells were dependent on costimulation with IL4. Although the percentages of class-switched cells in CD40-stimulated CD40/LMP1 cells were rather low, they were only 2-fold diminished compared with wt cells costimulated with anti-CD40 + IL4, and always significantly increased compared with anti-CD40–only stimulated controls. We tried to increase the frequency of class-switched cells using the agonistic CD40 antibody HM40–3, which is known to be more potent in inducing signaling and CSR. These attempts failed, however, because this antibody was unable to induce signaling in CD40/LMP1-expressing cells, for unknown reasons.

It was previously reported that EBV-infected primary B cells and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cell lines transfected with LMP1 switch to several isotypes.20 Since EBV-infected B cells are known to secrete cytokines,24 it could not be excluded that LMP1 acts in cooperation with these cytokines. We show that in primary naive CD40/LMP1-expressing B cells CSR to IgG1 is cytokine independent and due to an intrinsic effect of LMP1. Thus, LMP1 not only mimics CD40 receptor stimulation by CD40L in B cells, but has additional effects physiologically mediated by T helper cells. It will be interesting to elucidate the mechanism by which LMP1 induces CSR. A prerequisite for CSR is induction of the sterile transcripts.25 In contrast to the wt CD40+/+ control, anti-CD40 stimulation induced a 2-fold induction of the sterile γ1-transcripts after only 24 hours in CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells, which might be sufficient to open the locus for IgG1 CSR. However, so far we have been unable to identify a signaling pathway that is specifically activated in CD40/LMP1-expressing but not wt cells. The normal signaling pathways known to be activated by CD40 such as the MAP-kinases and NFκB were normal or dampened rather than enhanced in CD40/LMP1-expressing cells compared with wt cells after CD40 triggering. STAT6 has been shown to be essential for IL4-mediated CSR to IgG1.26 However, we could not detect phosphorylation of STAT6 or any of the other STATs suggested to be phosphorylated by LMP1-signaling—STAT1 and STAT327 —by Western blot analyses of anti-CD40–stimulated CD40/LMP1+//CD40−/− B cells (data not shown).

It has earlier been shown that LMP1 rescues extrafollicular CSR to IgG1 but not the germinal center formation in CD40-deficient mice.14 In contrast, a chimeric protein in which the cytoplasmic tail of LMP1 was exchanged with that of CD40 (LMP1/CD40) was not able to reconstitute either germinal formation or CSR to IgG1 in vivo (C.H.-H., unpublished observation, 2005). This might imply that both LMP1- and LMP1/CD40-expressing B cells have lost their ability to interact with T cells, because of their activated phenotype, but that CSR in LMP1-expressing mice is reconstituted by the intrinsic ability of LMP1 to induce cytokine- and T cell–independent CSR.

Why would it be advantageous for the virus to induce CSR? It has been shown that EBV persists in human memory B cells.28 It is still a controversial question whether EBV directly infects memory B cells, or whether naive B cells are infected and proceed to develop via normal B-cell differentiation processes into memory B cells.29,30 One advantage for the virus of persisting in memory B cells is that these cells are long lived. Memory B cells are characterized by the expression of class-switched Ig. Recently, it has been shown that mutant naive B cells expressing IgG1 instead of IgM and IgD display a long half-life in the mature B-cell compartment and that their maintenance is less dependent on the signaling molecule Ig-α.31 These data suggest that the IgG1 B-cell receptor delivers survival signals different from those provided by IgM. Thus the expression of IgG1 instead of IgM might give a survival advantage to EBV-infected cells. Therefore the intrinsic ability of LMP1 to induce CSR to IgG1 independent of T cells might enable an EBV-infected naive B cell to enter a long-lived B-cell compartment independent of a germinal center reaction.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sven Kracker for help with SHM analyses and critical discussions; Kevin Otipoby, Stefano Casola, and Lothar J. Strobl for critical discussions; Gabriele Marschall and Natalie Steck for help with mouse analyses; and Vigo Heissmeyer for help with TH2 differentiation. The injection of embryonic stem cells into blastocytes was done by M. Hafner and M. Ebel, Department of Experimental Immunology, GBF Braunschweig (supported by NGFN).

This work was supported by Deutsche Krebshilfe Az 106 310. J.R. was supported by a PhD scholarship of Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.R. designed and performed research and wrote the paper; C.H.-H., J.S., and A.C.H. helped to carry out experiments; W.M. contributed to the generation of transgenic mice; K.R. contributed to SHM analyses and helped prepare the paper; and U.Z.-S. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ursula Zimber-Strobl, Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology and Tumor Genetics, GSF-National Research Center for Environment and Health, Marchioninistrasse 25, D-81377 Munich, Germany; e-mail: strobl@gsf.de.