Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in the Western world and remains incurable with conventional therapies. Patients with relapsed or resistant CLL have a significantly shortened lifespan. MDM2 inhibitors have been developed and may have significant potential in the treatment of CLL. Clinical development of these compounds would be aided through knowledge of molecular predictors of activity. To understand determinants of sensitivity or resistance to MDM2 inhibitor therapy in CLL, we comprehensively analyzed a large cohort of CLL patient–derived samples for response to MDM2 inhibition and correlated these responses with clinically important biomarkers. Furthermore, we employed high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays to analyze genomewide changes of copy number and allele status, including that of p53. The results of these studies conclusively demonstrate that p53 status is the major determinant of response to MDM2 inhibitors in CLL. Additional defects in the p53 regulatory cascade do not appear operational in this leukemia. Further, we identify a novel subgroup of patients with CLL with early progressive disease that appears particularly sensitive to MDM2 inhibitor treatment. These data provide definitive evidence for target-specific and predictive activity and a rationale to proceed with this potentially important class of compounds in the treatment of CLL.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common form of adult leukemia in the Western world, and is characterized by a highly variable clinical course.1,2 Treatment of CLL is reserved for symptomatic patients or patients in advanced clinical stage. Despite improvements in response rates using chemoimmunotherapy combinations, CLL remains incurable, and patients refractory to fludarabine or patients who have suffered multiple disease relapses have a poor outlook.3-5 Therefore, novel therapeutics are needed to advance the outlook for afflicted patients.

Inhibitors of murine double minute 2 (Mdm2) represent a novel therapeutic approach.6-19 In cells with functional p53, the p53 activity is primarily inhibited through direct and tonic interaction with the MDM2 protein.20-22 Treatment of various tumor cells with inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 interaction results in rising p53 levels and subsequent induction of cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. For poorly understood reasons, nonmalignant cells appear relatively resistant to MDM2 inhibition.23,24

In CLL, in contrast to many solid tumors, p53 is mutated in only about 10% of patients at presentation and in 10% to 30% of patients with pretreated disease.25-28 Thus, small-molecule inhibitors that block the MDM2-p53 interaction could represent a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of most patients with CLL.

Human cancers are biologically heterogeneous and respond nonuniformly to therapeutic intervention. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying cancer susceptibility or resistance to specific drugs is essential to improve therapeutic outcome.

CLL is heterogeneous and several disease-related factors have been identified that classify CLL into biologically distinct and clinically relevant subtypes. Investigation into these subtypes has revealed clues about mechanisms of disease and patient prognosis.2,29,30

Lack of mutation in the immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region (IgVH) genes, increased expression of zeta-associated protein of 70 kDa (ZAP-70), and mutations involving p53 and/or ATM genes are some of the molecular parameters that have been associated with an aggressive disease course, shortened disease-free intervals, and compromised survival.28,31-39

Importantly, interphase fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) has identified chromosomal changes in approximately 80% of patients with CLL, and the presence of select chromosomal abnormalities, such as del(17p), has proven to be a prognostic indicator for response to therapy, disease progression after therapy, and survival.29,40,41

Given that loss of p53 or genes important for p53-induced apoptosis may confer resistance to therapies, including MDM2 inhibitors, we compared data from in vitro treatments of tumor cells from over 100 patients with CLL with 2 MDM2-inhibiting compounds to patient-specific, unbiased, genomewide copy number analyses using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays and measurements of clinically relevant biomarkers.42-47

Methods

Patients

Between January 2005 and July 2007, 179 patients with CLL were enrolled into a prospective CLL study at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center. The trial was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRBMED #2004-0962), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Eligibility criteria required a diagnosis of CLL based on the National Cancer Institute Working Group Guidelines.48 Eligible patients needed to have an absolute lymphocytosis (greater than 5000 mature lymphocytes per microliter), and lymphocytes needed to express CD19, CD23, sIg (weak), and CD5 in the absence of pan–T-cell markers. Five patients enrolled on the study were excluded from analysis (diagnoses: large cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, Crohn disease, and CLL with concurrent AML). Three posttreatment patient samples gave insufficient DNA for analysis and thus were excluded from analysis.

Of these 179 patients, samples from 171 cases were used for this study. For MDM2 inhibitor kill assays, 106 cases were selected to represent various CLL subtypes and were enriched for known p53 abnormalities. Eighty-five cases were previously untreated and twenty-one previously treated (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The 85 untreated cases were previously analyzed for CLL biomarkers as described.49

CLL treatment was defined as cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or monoclonal antibody therapy for CLL and/or associated autoimmune cytopenias.

At enrollment, clinical information, including Rai stage, was collected on all patients.50

Cell isolation

Cell purification.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with CLL were isolated by Ficoll gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), aliquoted into fetal calf serum (FCS) with 10% DMSO, and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen.

Flow cytometry.

Cryopreserved CLL cells were washed and stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD19 and FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Propidium iodide was added to a concentration of 1 μg/mL to discriminate dead cells, and viable CD19+ and CD3+ single-positive cells were sorted on a high-speed FACS Aria (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) sorter.

Array data analysis

Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) data files were generated from SNP chips after hybridization via scanners at the University of Michigan Microarray Core facility and imported into the Affymetrix Gene Chip Operating Software and GeneChip DNA Analysis Software suites. dChip used native Affymetrix .CEL files and text-formatted .CHP files from GDAS to generate copy number heatmap displays.51

Loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) analysis and LOH display across chromosomes between CD19+ tumor cell–derived DNA and buccal DNA were performed using the LOH tool.47

Mutation Surveyor software (SoftGenetics, State College, PA) was used to compare experimental p53 sequences against GenBank sequence (NM_000546) or genomic sequences, as well as by visual inspection of sequence tracings.

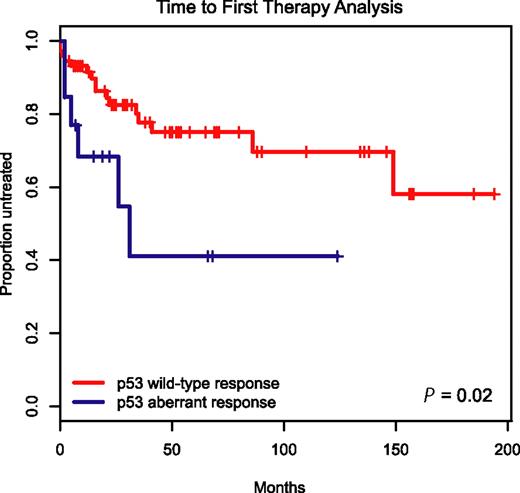

Assessment of association between p53 response by immunoblotting before and after MDM2 inhibition and clinical outcome

Time-to-first-treatment (TTFT) was the sole clinical end point that we used. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the survivor function to first treatment for each subgroup (CLL cases with and without aberrant p53 induction by immunoblotting), and the log-rank test was used to calculate P values to test for significant differences in the survivor function between subgroups.

Assessment of the relationship between MDM2 inhibitor ex vivo IC50 kill values and clinical outcome

Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess univariate associations between TTFT and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) value for p53 wild-type samples. In these models, TTFT is related to a linear predictor of the form b*IC50. The fitted coefficient b means that given 2 untreated subjects that differ one unit in IC50, the subject with higher IC50 has approximately exp(b) times greater risk of going onto treatment. Coefficient estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values based on the log-rank test are given for each MDM2 inhibitor.

Determination of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene (IgVH) mutation status

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify IgVH regions using CLL sample CD19+-sorted, cell-derived genomic DNA or cDNA as templates. Trizol was used to purify total RNA, and the Superscript III first-strand reverse transcription (RT)–PCR kit was used to generate first-strand cDNA (random primed; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primers were a mixture of 7 FR1-primers using the BIOMED2 consortium primers and the modified J-consensus primer 5′-ACCTGAGGAGACGGTGACCAGGGT-3′ (Jc).52 Amplifications were done using Platinum-PFX (Invitrogen) and optimized using gradient PCR conditions. Products were fractionated on 2% agarose gels, excised and eluted using the Qiaquick gel extraction kit, and directly sequenced using primer Jc. Products were also cloned using the Zero Blunt Topo PCR cloning kit (PCR Blunt II topo vector; Invitrogen) and multiple clones per patient were sequenced using M13 primers. Sequences were compared against the IgVH-database using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Ig-Blast search engine (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/igblast/). A 98% homology to germ line was used as the cut-off for unmutated status assignment.

Determination of percentage of ZAP-70–positive cells using multiparameter flow cytometry analysis

ZAP-70 analysis was based on the method of Rassenti et al with minor modifications.36 From 200,000 to 1 million cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with CLL were thawed into warmed medium, washed, and stained with directly conjugated anti-CD19PE and anti-CD3APC (eBioscience) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, then permeabilized with 0.1% saponin. Anti–ZAP-70 clone 1E7.2 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) was added in saponin for 45 minutes. Cells were again washed and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde and analyzed on a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Healthy donor PBMCs were used to set markers such that 0.5% of events were in the upper right quadrant, with CD19+ cells along the y axis and ZAP-70–positive cells along the x axis. The percent ZAP-70–positive cells for CLLs was determined using this marker setting. Samples were classified as ZAP-70 positive if greater than 20% of CD19+ cells were also ZAP-70 positive.

p53 genomic DNA sequencing

Primers to amplify exons 5/6, 7, and 8/9 of human p53 and adjacent intronic sequences were designed using the primer 3 program. The sequence of the primers used is as follows: p53-E5/6-F, 5′-ggaggtgcttacgcatgtttt; p53-E5/6-R, 5′-gggaggtcaaataagcagca; p53-E7-F, 5′-aaaaaggcctcccctgct; p53-E7-R, 5′-tggaagaaatcggtaagaggtg; p53-E8/9-F, caagggtggttgggagtaga; p53-E8/9-R, ccccaattgcaggtaaaaca. PCR products were generated using DNA templates from FACS-sorted CD19+ or CD3+ cells. Amplifications were done using Taq polymerase. PCR amplicons were prepared for direct sequencing with internal nested sequencing primers using the exonuclease/shrimp alkaline phosphatase method (USB, Cleveland, OH).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed for patient samples at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, as a routine clinical test, with the following published chromosomal target regions: 6cen (D6Z1), 6q23.3 (c-myb locus), 11 cen (D11Z1), 11q13 (CCND1-XT), 11q22.3 (ATM), 12 cen (D12Z3), 12q15 (MDM2), 13q14 (D13S319), 13q34 (LAMP1), 14q32 (IGH-XT), 17 cen (D17Z1), 17p13.1 (p53).

Preparation of sample DNA for hybridization to Affymetrix 50k-XbaI–mapping arrays and assay characteristics

A novel oligonucleotide platform, the 50k SNP chip, was introduced in 2004 by Affymetrix. Selected technical characteristics of the 50k SNP chips are a total combined number of approximately 58 000 SNPs, a median intermarker distance of about 16 kb, a mean intermarker distance of 47 kb, and an average heterozygosity of 0.29.

Sorted CD19+ or CD3+ cells or buccal swabs were digested overnight in 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, and 100 μg/mL Proteinase K (Invitrogen) at 56°C. DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform and precipitated using ammonium acetate, ethanol, and glycogen. DNA (250 μg) was digested for 10 hours at 37°C, and the samples were subsequently ligated, PCR-amplified, fragmented, and labeled according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridization of labeled DNA fragments to the 50k-XbaI–mapping arrays was performed in an Affymetrix Hybridization Oven 640 for 16 hours at 48°C with rotation at 60 rpm. Washing and staining was done on an Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450. Scanning was done using an Affymetrix Scanner 3000 7G with autoloader. Data files were archived and transferred using CAB (Windows cabinet) files.

CD19+ cell purification and MDM2 inhibitor treatment

Cryopreserved PBMCs derived from patients with CLL were washed and recovered by centrifugation and then treated with antihuman CD3 (no. 130-050-101; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and antihuman CD14 microbeads (no. 130-050-201; Miltenyi Biotec) per manufacturer's recommendations. Cell suspensions were run through Miltenyi MACS separation LS columns (no. 130-042-401) in order to negatively enrich for CD19+ B cells. This resulted in greater than 95% CD19+ cells.

MI-63 and MI-61 were synthesized using previously published methods.15,16 Nutlin3 was provided by Dr Wang. We have previously reported that MI-63 binds to MDM2 with a Ki value of 3 nM. MI-61 is a close homologue of MI-63 and binds MDM2 with more than 3000-fold lower affinity, and was thus used as an inactive control in this study.

CD19+ cells were suspended at 5 × 105 cells per well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and treated in duplicate incubations with the MI-63 compound at concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM. Cells were treated in parallel duplicate incubations with Nutlin3 at concentrations of 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 μM. In addition, cells at a concentration of 2 × 106 per well were treated with 10 μM MI-63, 20 μM Nutlin3, and 10 μM MI-61, incubated for 36 hours, washed and frozen for immunoblotting at a later time.

All cells were incubated for 36 hours at 37°C, at which time they were prepared for staining with Aposcreen Annexin V-PE (no. 10 040-09; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and PI (P4170; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and analyzed by flow cytometry using a Beckman Coulter Epics XL (Fullerton, CA). Sample response to drug was calculated based on indexing the percent live cell number in the untreated control of each CLL as 100%, and then recalculating percent live at each drug concentration for individual cases for all data points. IC50 calculations were performed using XL-fit (IDBS, Guildford, United Kingdom).

For each dose level, a 2-sample t test was performed to compare the mean response (percent cell kill) in p53 or 17p wild-type samples to the mean response in p53 mutant or 17p deleted samples. Results are displayed as the mean plus or minus one standard deviation, with an asterisk to denote the comparisons that were significant at the P ≤ .01 level.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting to measure p53 levels after MDM2 inhibition was performed on cell lysates from treated cells stored frozen in pellets. Cell pellets were directly lysed in 100 μL of 1× Laemmli SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) buffer in 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM EDTA. Protein was fractionated on 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membrane, then blocked for 1 hour in 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline–Tween-20 (TBS-T). Membranes were incubated in anti-p53 mouse mAb (Ab-6) in milk/TBS-T (Pantropic Mouse mAb DO-1; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at a dilution of 1:500, washed, and finally incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti–mouse Ig at 1:10 000 dilution (NXA931; GE Healthcare). The membranes were developed using ECL Plus Detection (GE Healthcare) reagents.

Results

Patient characteristics

Included in this study are samples and clinical data from 171 patients with CLL who are enrolled in an ongoing prospective CLL profiling study. Characteristics for 106 patients who were analyzed for MDM2 inhibitor-mediated cell kill are summarized in Table 1 and detailed in Table S1.

Eighty-five (80%) patients were previously untreated, and 21 (20%) patients were pretreated with either alkylator- or purine analog–based therapies. Patient samples were characterized for p53 mutations, immunoglobulin variable gene mutations (IgVH-mutations), ZAP-70 expression, and for selected CLL-associated chromosomal aberrations using FISH, as described.49

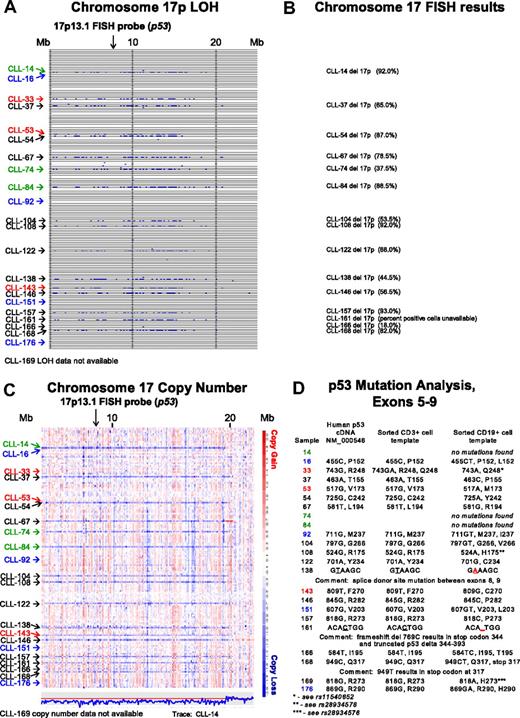

p53 mutations in CLL are associated with monoallelic 17p deletion, with regions of copy-neutral LOH at 17p not detectable by FISH, or without detectable changes on 17p

Patients with CLL with del17p spanning the p53 gene have a poor prognosis, with an average survival of about 3 years. As a prerequisite to understanding in detail the relationship of p53 allele status, p53 mutations, and response to MDM2 inhibition in CLL, we defined 171 patients with CLL for p53 allele status, p53 LOH, and p53 mutations. We analyzed genomic profiles of patients with CLL using the Affymetrix 50k SNP platform, clinical FISH data using a probe spanning the p53 locus, and p53 sequence data for exons 5 to 9.

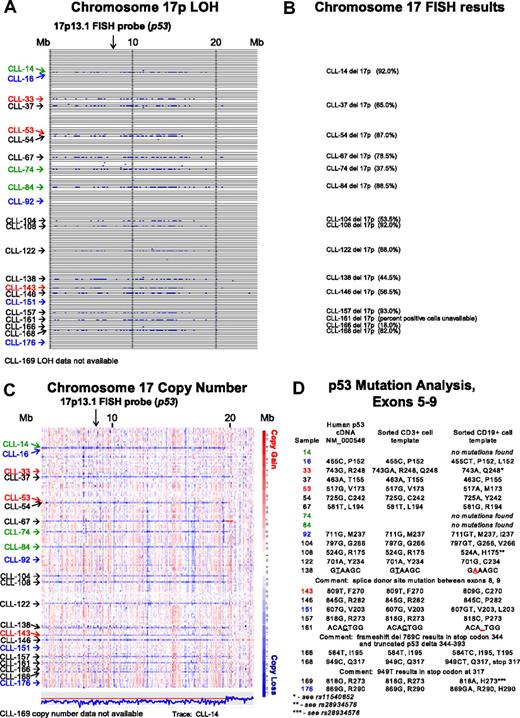

In Figure 1A, LOH analysis (buccal DNA versus CD19+ CLL cells) for chromosome 17p for all SNPs and for all patients is shown. Through comparison of LOH calls (Figure 1A) with clinical FISH data (Figure 1B), we noted that 3 patients (CLL nos. 33, 53, and 143) were not previously known to carry abnormalities at 17p. We therefore analyzed copy number estimates for 17p for all patients and found that CLL nos. 33 and 53 (Figure 1C red) had a normal 2N state at 17p whereas CLL no. 143 demonstrated del17p (1N). Therefore, copy-neutral LOH (uniparental disomy) exists at 17p (CLL nos. 33 and 53) and would escape detection using the clinically important FISH assay.

Comparative analysis of chromosome 17p LOH, copy number estimates, FISH, and p53 mutation analysis. Text files generated through use of the Affymetrix programs GDAS and Copy Number Tool for all patients were imported into the LOH tool, and all individual positions of LOH between buccal DNA and paired tumor DNA were graphed as a blue tick mark across the length of the chromosomes. Copy number estimates for all SNP positions for all patients were generated through dChipSNP, as described, and displayed across the length of the chromosomes. Copy losses are displayed with blue colors, copy gains with red colors. The physical position of SNPs is not linear along the displayed portions of the chromosome. (A) LOH display for chromosome 17p. Each row represents one patient. Vertical solid lines indicate 10-Mb intervals. The location of the commonly used FISH probe spanning the p53 gene at 17p13.1 is marked with a vertical arrow. (B) Chromosome 17 FISH results from all patients with del17p by clinical FISH panel (Mayo Clinic) with the estimated percentage of positive cells in parentheses. (C) Copy number display for chromosome 17p. The location of the commonly used FISH probe spanning the p53 gene at 17p13.1 is marked with a vertical arrow. The estimated copy numbers for all SNP positions for CLL no. 14 are shown below the chromosome 17p display, with the red line indicating the 2N state. (D) p53 Mutation analysis for exons 5 to 9. Sample numbers are indicated in column 1. The nucleotide and amino acid residue for that position in the cDNA NM 000546 or genomic DNA (same result) is shown in column 2. The nucleotide and amino acid residue for that position in FACS-sorted CD3+ cells (somatic control DNA) is shown in column 3, and the nucleotide and amino acid residue for that position in FACS-sorted CD19+ cells is shown in column 4. In panels A and C, patients with CLL with del17p and p53 wild-type status are indicated in green. Patients with CLL without del17p and p53 mutant status are indicated in blue. Patients with CLL with del17p and p53 mutant status are indicated in black.

Comparative analysis of chromosome 17p LOH, copy number estimates, FISH, and p53 mutation analysis. Text files generated through use of the Affymetrix programs GDAS and Copy Number Tool for all patients were imported into the LOH tool, and all individual positions of LOH between buccal DNA and paired tumor DNA were graphed as a blue tick mark across the length of the chromosomes. Copy number estimates for all SNP positions for all patients were generated through dChipSNP, as described, and displayed across the length of the chromosomes. Copy losses are displayed with blue colors, copy gains with red colors. The physical position of SNPs is not linear along the displayed portions of the chromosome. (A) LOH display for chromosome 17p. Each row represents one patient. Vertical solid lines indicate 10-Mb intervals. The location of the commonly used FISH probe spanning the p53 gene at 17p13.1 is marked with a vertical arrow. (B) Chromosome 17 FISH results from all patients with del17p by clinical FISH panel (Mayo Clinic) with the estimated percentage of positive cells in parentheses. (C) Copy number display for chromosome 17p. The location of the commonly used FISH probe spanning the p53 gene at 17p13.1 is marked with a vertical arrow. The estimated copy numbers for all SNP positions for CLL no. 14 are shown below the chromosome 17p display, with the red line indicating the 2N state. (D) p53 Mutation analysis for exons 5 to 9. Sample numbers are indicated in column 1. The nucleotide and amino acid residue for that position in the cDNA NM 000546 or genomic DNA (same result) is shown in column 2. The nucleotide and amino acid residue for that position in FACS-sorted CD3+ cells (somatic control DNA) is shown in column 3, and the nucleotide and amino acid residue for that position in FACS-sorted CD19+ cells is shown in column 4. In panels A and C, patients with CLL with del17p and p53 wild-type status are indicated in green. Patients with CLL without del17p and p53 mutant status are indicated in blue. Patients with CLL with del17p and p53 mutant status are indicated in black.

It is commonly assumed that the del17p indicates that p53 is mutated on the retained allele. We decided to test this relationship through comparison of dChip SNP-based copy number estimates for 17p, FISH data, and p53 mutation status.

As can be seen in Figure 1C and D, 3 of 15 patients (CLL nos. 14, 74, and 84; green) with copy loss at 17p had no p53 mutations in the retained allele. The 2 patients with LOH but no 17p copy loss (CLL nos. 33 and 53; red) had either a polymorphism in the germ line (CD3+ cells as template) that encoded for an amino acid change (CLL no. 33 with either p53 R248 and Q248 in the germ line) that converted to Q248 in the CLL cells, or a homozygous mutation (CLL no. 53).

CLL nos. 16, 92, 151, and 176 (Figure 1C blue), which had neither LOH nor copy loss at 17p, carried p53 mutations.

Finally, multiple CLL cases (Figure 1A,C black), with both LOH and copy loss at 17p, carried p53 mutations on the remaining allele.

p53 protein levels in CLL samples at baseline and in response to MDM2 inhibitors

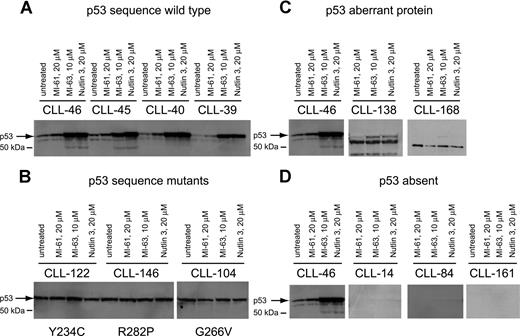

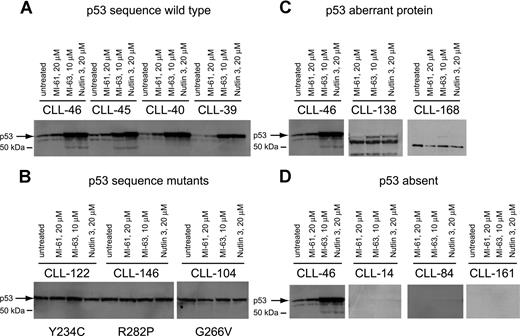

To corroborate p53 sequence data and to detect additional p53 aberrations, we measured p53 levels before and after MDM2 inhibitor treatment by immunoblotting in purified CD19+ tumor cells from all 106 CLL cases studied.

As expected, p53 levels were elevated after MDM2 inhibitor treatment in all samples with wild-type p53 status when compared with either untreated cells or cells treated with the inactive compound MI-61 (Figure 2A). p53 levels were high and were not further induced in samples with known p53 point mutations (Figure 2B).

p53 expression levels at baseline and in response to MDM2 inhibition in CLL. Total protein from untreated, MI-61–treated, and MDM2 inhibitor (MI-63, Nutlin3)–treated cell samples was fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and prepared for immunoblotting with anti-p53 mAb. Membrane was developed using HRP-conjugated antimouse Ab followed by ECL-plus. (A) Four different CLL samples with wild-type p53 exon 5 to 9 sequence; treatments for individual samples/lanes are indicated. (B) Three different CLL samples with mutant p53 exon 5 to 9 sequence; treatments for individual samples/lanes are indicated. (C) Two CLL samples (nos. 138 and 168) with frameshift mutants of p53 compared with a wild-type CLL sample (no. 46); treatments for individual samples/lanes are indicated. (D) Three CLL samples with absent p53 expression (nos. 14, 84, and 161) compared with a wild-type CLL sample (no. 46). The position of wild-type p53 is indicated by an arrow.

p53 expression levels at baseline and in response to MDM2 inhibition in CLL. Total protein from untreated, MI-61–treated, and MDM2 inhibitor (MI-63, Nutlin3)–treated cell samples was fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and prepared for immunoblotting with anti-p53 mAb. Membrane was developed using HRP-conjugated antimouse Ab followed by ECL-plus. (A) Four different CLL samples with wild-type p53 exon 5 to 9 sequence; treatments for individual samples/lanes are indicated. (B) Three different CLL samples with mutant p53 exon 5 to 9 sequence; treatments for individual samples/lanes are indicated. (C) Two CLL samples (nos. 138 and 168) with frameshift mutants of p53 compared with a wild-type CLL sample (no. 46); treatments for individual samples/lanes are indicated. (D) Three CLL samples with absent p53 expression (nos. 14, 84, and 161) compared with a wild-type CLL sample (no. 46). The position of wild-type p53 is indicated by an arrow.

Aberrant short p53 protein was detected in 2 cases (Figure 2C) and was associated with relative resistance to MDM2 inhibitor treatment.

Finally, we detected 3 CLL cases with essentially absent p53 levels that were unchanged by MDM2 inhibitor treatment (Figure 2D). All 3 cases carried monoallelic del17p. These cases displayed relative resistance to MDM2 inhibitor treatment, comparable to p53 sequence mutants as described in “Measurements of MDM2 inhibitor-mediated cell kill in a large CLL cohort.”

Measurements of MDM2 inhibitor-mediated cell kill in a large CLL cohort

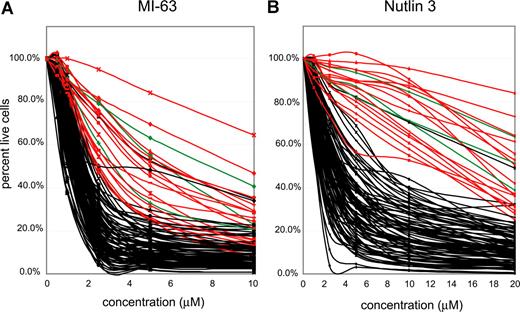

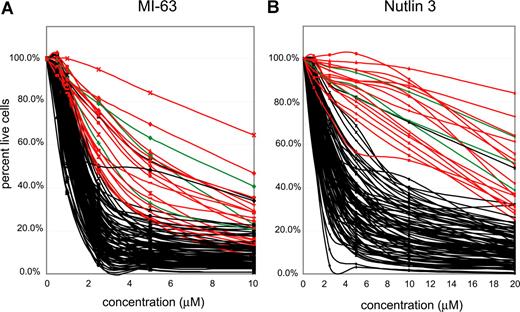

Highly purified CD19+ cells (see “Methods”) from 106 patients with CLL were incubated with 2 different MDM-2 inhibitors (MI-63 and Nutlin3) at the indicated concentrations (Figure 3A,B) for approximately 36 hours, and apoptotic (annexin-V staining) and necrotic (PI staining) cell death was measured using flow cytometry. Untreated aliquots of individual case cells that did not stain with annexin-V or PI were used as a baseline, indexed to 100%, to compute the cell death fraction induced by the drug for each CLL case.

p53 status is the primary determinant of MDM2 cell kill in CLL. CLL samples (n=106) were enriched for CD19+ cells through negative selection and incubated for 36 hours with various concentrations of either MI-63 or Nutlin3. Samples were prepared for Annexin-V and PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry, and the residual live and nonapoptotic cell fraction was calculated for each concentration by comparison with the untreated control incubation. (A) MI-63 assay results. Red indicates p53 sequence mutants; green, CLL cases with absent p53 expression; black, wild-type p53 status. (B) Nutlin3 assay results. Red indicates p53 sequence mutants; green, CLL cases with absent p53 expression; black, wild-type p53 status.

p53 status is the primary determinant of MDM2 cell kill in CLL. CLL samples (n=106) were enriched for CD19+ cells through negative selection and incubated for 36 hours with various concentrations of either MI-63 or Nutlin3. Samples were prepared for Annexin-V and PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry, and the residual live and nonapoptotic cell fraction was calculated for each concentration by comparison with the untreated control incubation. (A) MI-63 assay results. Red indicates p53 sequence mutants; green, CLL cases with absent p53 expression; black, wild-type p53 status. (B) Nutlin3 assay results. Red indicates p53 sequence mutants; green, CLL cases with absent p53 expression; black, wild-type p53 status.

IC50 values for MI-63–mediated kill ranged from 0.3 μM for the most sensitive case to greater than 10 μM for the most resistant case (Table S2). Similar compound sensitivity profiles for the Nutlin3 compound were 0.5 μM to greater than 40 μM.

As can be seen in Figure 3A and B, the vast majority of CLL samples with wild-type p53 (black lines) displayed susceptibility to kill by both compounds. Importantly, all 16 CLL cases with known p53 mutations (red curves) or absent p53 expression (3 cases, green curves, see also Figure 2D) were relatively resistant. Mean IC50 values for MI-63 or Nutlin3 for CLL cases without (87 cases) or with p53 abnormalities (sequence mutants or absent expression, 19 cases) were 1.52/5.4 μM and 3.55/22.9 μM, respectively.

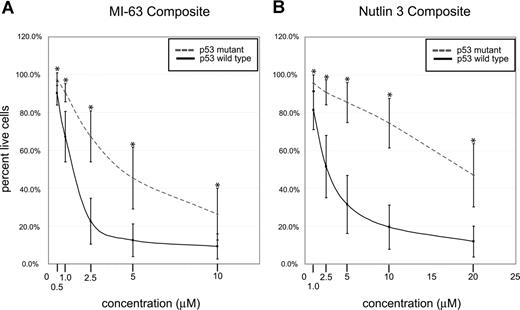

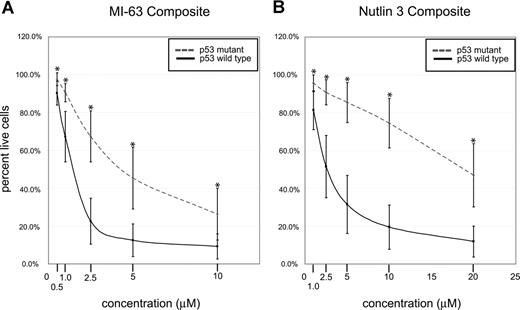

Composite analysis of MDM2 inhibitor-induced fractional cell kill demonstrated highly statistically significant differences between the mean of the response in p53 wild-type and mutant CLL samples for both compounds (Figure 4A,B; all P values were less than .001).

p53 status is the primary determinant of MDM2 cell kill in CLL (composites). CLL samples (n=106) were enriched for CD19+ cells through negative selection and incubated for 36 hours with various concentrations of either MI-63 or Nutlin3. Samples were prepared for annexin-V and PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry, and the residual live and nonapoptotic cell fraction was calculated for each concentration through comparison with the untreated control incubation. (A) MI-63 assay result composites. Dashed line indicates p53 sequence mutants and cases with absent p53 expression; solid line, wild-type p53 status. (B) Nutlin3 assay results. Dashed line indicates p53 sequence mutants and cases with absent p53 expression; solid line, wild-type p53 status. Standard deviations are indicated by vertical black bars. Statistically different data points (mean) are marked with asterisks. Results are displayed as the mean plus or minus one standard deviation, with an asterisk to denote the comparisons that were significant at the P ≤ .001 level.

p53 status is the primary determinant of MDM2 cell kill in CLL (composites). CLL samples (n=106) were enriched for CD19+ cells through negative selection and incubated for 36 hours with various concentrations of either MI-63 or Nutlin3. Samples were prepared for annexin-V and PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry, and the residual live and nonapoptotic cell fraction was calculated for each concentration through comparison with the untreated control incubation. (A) MI-63 assay result composites. Dashed line indicates p53 sequence mutants and cases with absent p53 expression; solid line, wild-type p53 status. (B) Nutlin3 assay results. Dashed line indicates p53 sequence mutants and cases with absent p53 expression; solid line, wild-type p53 status. Standard deviations are indicated by vertical black bars. Statistically different data points (mean) are marked with asterisks. Results are displayed as the mean plus or minus one standard deviation, with an asterisk to denote the comparisons that were significant at the P ≤ .001 level.

Only a few CLL cases with wild-type p53 status and wild-type p53 induction by immunoblotting in response to MDM2 inhibition displayed resistance to MDM2 inhibitor treatment that was comparable to the known p53 mutant cases (Figure 3A,B). Therefore, p53 status emerged as the major determinant of responsiveness to MDM2 inhibitors in CLL.

The influence of established clinically important biomarkers on response to MDM2 inhibitors in CLL

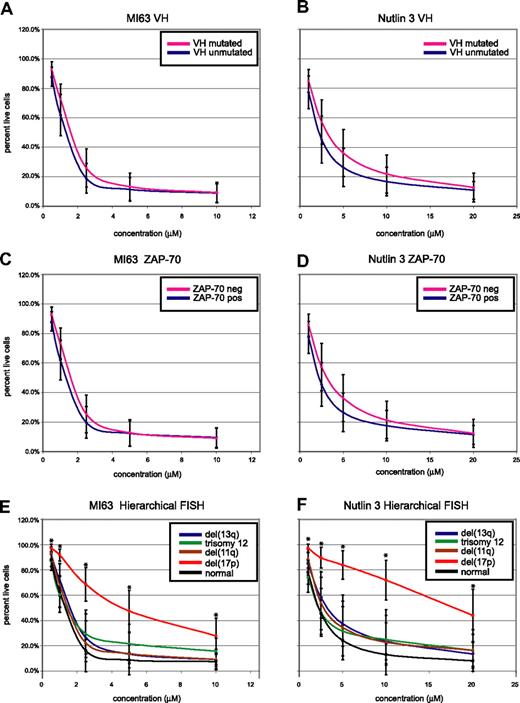

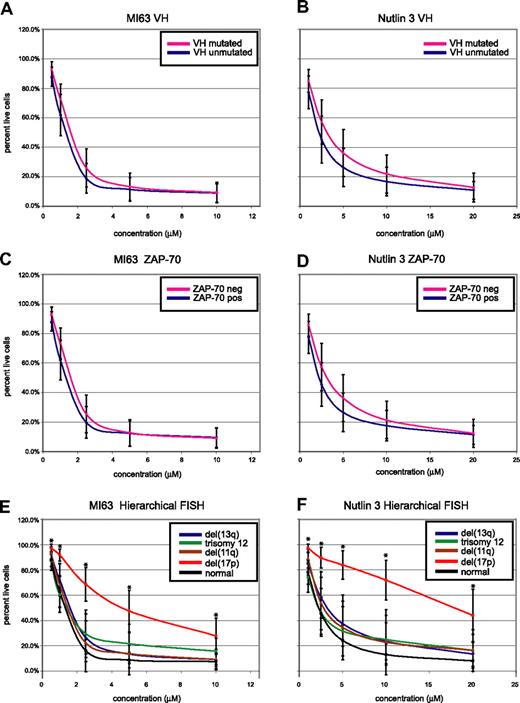

We also assessed whether the presence or absence of unfavorable biomarkers used clinically in CLL, including unmutated immunoglobulin variable genes (IgVH-unmutated), expression of ZAP-70, or presence of select FISH findings, predicted for MDM2 treatment response (Figure 5A-F).

CLL cell kill by MDM2 inhibitors is independent of IgV-mutation status or ZAP-70 expression but dependent on the presence of del17p. CLL samples (n=106) were enriched for CD19+ cells through negative selection and incubated for 36 hours with various concentrations of either MI-63 or Nutlin3. Samples were prepared for annexin-V and PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry, and the residual live and nonapoptotic cell fraction was calculated for each concentration through comparison with the untreated control incubation. (A) MI-63 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the IgVH-mutated CLL group; black, the IgVH-unmutated CLL group. (B) Nutlin3 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the IgVH-mutated CLL group; black, the IgVH-unmutated CLL group. (C) MI-63 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the ZAP-70–negative CLL group; black, the ZAP-70–positive CLL group. (D) Nutlin3 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the ZAP-70–negative CLL group; black, the ZAP-70–positive CLL group. (E) MI-63 assay results, composites, including cases with p53 aberrations; various hierarchical FISH categories are indicated. (F) Nutlin3 assay results, composites, including cases with p53 aberrations; various hierarchical FISH categories are indicated. Standard deviations are indicated by vertical black bars. Results are displayed as the mean plus or minus one standard deviation, with an asterisk to denote the comparisons that were significant at the P ≤ .001 level.

CLL cell kill by MDM2 inhibitors is independent of IgV-mutation status or ZAP-70 expression but dependent on the presence of del17p. CLL samples (n=106) were enriched for CD19+ cells through negative selection and incubated for 36 hours with various concentrations of either MI-63 or Nutlin3. Samples were prepared for annexin-V and PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry, and the residual live and nonapoptotic cell fraction was calculated for each concentration through comparison with the untreated control incubation. (A) MI-63 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the IgVH-mutated CLL group; black, the IgVH-unmutated CLL group. (B) Nutlin3 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the IgVH-mutated CLL group; black, the IgVH-unmutated CLL group. (C) MI-63 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the ZAP-70–negative CLL group; black, the ZAP-70–positive CLL group. (D) Nutlin3 assay results, composites, excluding cases with p53 aberrations. Red indicates the ZAP-70–negative CLL group; black, the ZAP-70–positive CLL group. (E) MI-63 assay results, composites, including cases with p53 aberrations; various hierarchical FISH categories are indicated. (F) Nutlin3 assay results, composites, including cases with p53 aberrations; various hierarchical FISH categories are indicated. Standard deviations are indicated by vertical black bars. Results are displayed as the mean plus or minus one standard deviation, with an asterisk to denote the comparisons that were significant at the P ≤ .001 level.

As can be seen in Figure 5A through D, after exclusion of CLL cases with either known p53 mutations or absent p53 expression, neither IgV-mutation status nor ZAP-70 expression status influenced susceptibility to MDM2 treatment.

Conversely, patients with del17p by hierarchical FISH (not excluding cases with p53 aberrations, as these molecular abnormalities demonstrated 100% linkage) displayed relative resistance to MDM2 inhibitor treatment (mean IC50 values of 5.7/23.1 μM for MI-63 and Nutlin3, respectively). Comparing the response of the patients with del17p to all other FISH categories combined demonstrated a highly significant difference for comparison of the mean for all drug concentrations (all P values were less than .001).

CLL cases in other hierarchical FISH categories, including cases with del11q (spanning ATM), del13q14, trisomy 12, or a normal FISH, appeared equally sensitive to MDM2 inhibitor treatment (mean IC50 values of 1.3/2.8 μM, 1.6/4.1 μM, 1.7/3.7 μM, and 1.3/2.6 μM for MI-63 and Nutlin3, respectively).

The response to MDM2 inhibitors is independent of prior therapies for CLL

While an increased incidence of acquired adverse FISH abnormalities including del17p or p53 mutations is known to occur in CLL at time of relapse, little is known about additional molecular changes that may adversely affect susceptibility to MDM2 inhibitor treatment.

Stratified analysis of the MDM2 inhibitor-mediated cell kill sensitivity presented in “The influence of established clinically important biomarkers on response to MDM2 inhibitors in CLL” by treatment status (untreated vs pretreated and excluding patients with known p53 mutations) uncovered that prior therapies did not influence response to MDM2 inhibition (Figure S1A,B).

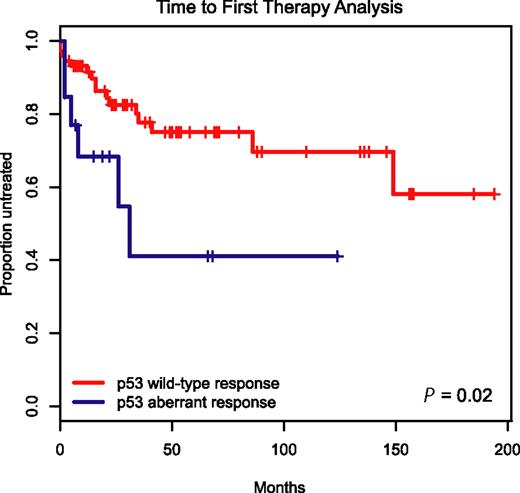

Aberrant MDM2 inhibitor-induced p53 protein induction predicts for rapid CLL disease progression

To determine the clinical prognostic importance of detecting p53 aberrations through immunoblotting before and after MDM2 inhibitor treatment in CLL, we employed the Kaplan-Meier method and display time-to-first-therapy (TTFT) data for the 19 patients with aberrant p53 induction versus the remaining 87 cases with wild-type p53 induction in Figure 6.

Aberrant induction or expression of p53 in response to MDM2 inhibition predicts for aggressive disease. Display of time-to-first-therapy estimates for CLL cases with aberrant p53 induction (blue line) by immunoblotting as opposed to cases with p53 wild-type immunoblotting pattern (red line), using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Aberrant induction or expression of p53 in response to MDM2 inhibition predicts for aggressive disease. Display of time-to-first-therapy estimates for CLL cases with aberrant p53 induction (blue line) by immunoblotting as opposed to cases with p53 wild-type immunoblotting pattern (red line), using the Kaplan-Meier method.

TTFT was 29 months for the group of patients with aberrant p53 induction as opposed to not reached for the group with wild-type p53 response (P = .02), indicating an aggressive disease course for patients with aberrant p53 function.

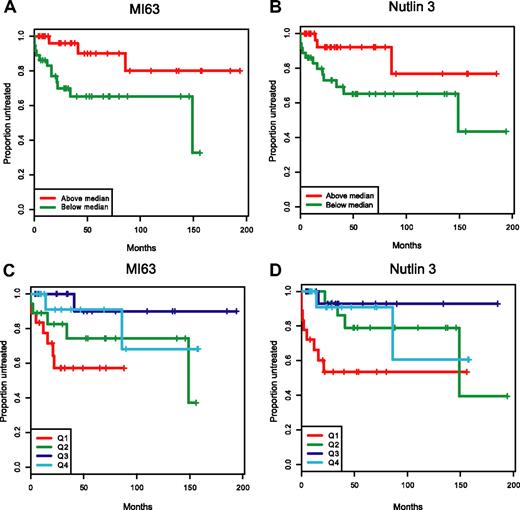

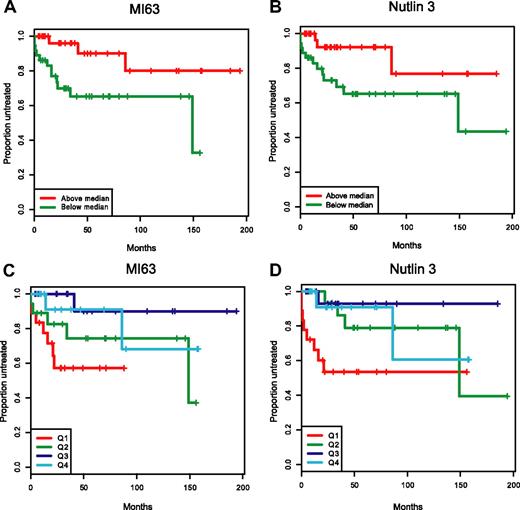

High sensitivity to MDM2 inhibitors in CLL cases without p53 aberration predicts for aggressive CLL

Further correlative analysis of TTFT versus sensitivity to MDM2 inhibitors ex vivo for all CLL cases with wild-type p53 immunoblotting response before and after MDM2 inhibitor treatment (excluding the cases with aberrant p53 response) gave unexpected results: Untreated patients who displayed high sensitivity to MDM2-inhibitor treatment ex vivo progressed significantly more rapidly and required therapy earlier than patients with relatively less sensitive CLL cells. Using Cox proportional hazard modeling, a highly statistically significant correlation was found between low IC50 values and shorter TTFT (MI-63: P = .006, coefficient of −1.71 [range −3.07 - −0.35]; Nutlin3: P = .02, coefficient −0.50 [range −0.98 - −0.03]; see “Methods”).

In Figure 7A-D, we have graphically displayed Kaplan-Meier estimates of TTFT estimates for p53 wild-type patients with IC50 values below or above the median for either MI-63 or Nutlin-3 (Figure 7A,B) and for p53 wild-type patients grouped by IC50 value quartiles (Figure 7C,D). Either display representatively demonstrates the shortened time to first therapy for the p53 wild-type patient groups with low ex vivo MDM2 inhibitor IC50 kill values as opposed to patients with cells with high ex vivo IC50 values.

Patients with wild-type p53 and with low MDM2 inhibitor ex vivo cell kill IC50 values have more aggressive disease. Representative display of time-to-first-therapy (TTFT) estimates for 87 CLL cases with p53 wild-type immunoblotting pattern, using the Kaplan-Meier method, grouped by MDM2 inhibitor treatment. (A) MI-63 display of TTFT for groups below (green) and above (red) the median IC50 value. (B) Nutlin3 display of TTFT for groups below (green) and above (red) the median IC50 value. (C) MI-63 display of TTFT for quartiles of IC50 values (Q1-Q4, with Q1 lowest to Q4 highest). (D) Nutlin3 display of TTFT for quartiles of IC50 values (Q1-Q4, with Q1 lowest to Q4 highest).

Patients with wild-type p53 and with low MDM2 inhibitor ex vivo cell kill IC50 values have more aggressive disease. Representative display of time-to-first-therapy (TTFT) estimates for 87 CLL cases with p53 wild-type immunoblotting pattern, using the Kaplan-Meier method, grouped by MDM2 inhibitor treatment. (A) MI-63 display of TTFT for groups below (green) and above (red) the median IC50 value. (B) Nutlin3 display of TTFT for groups below (green) and above (red) the median IC50 value. (C) MI-63 display of TTFT for quartiles of IC50 values (Q1-Q4, with Q1 lowest to Q4 highest). (D) Nutlin3 display of TTFT for quartiles of IC50 values (Q1-Q4, with Q1 lowest to Q4 highest).

Discussion

This study examines the efficacy of in vitro MDM2 inhibitor-mediated cell kill of purified primary CLL tumor cells in a large cohort of patients with CLL for whom comprehensive clinical risk data are available and for whom high-quality genomewide subchromosomal copy number and LOH data have been accumulated.

From this it has been possible to firmly conclude that p53 status is the major determinant of responsiveness to MDM2 inhibitor treatment in CLL.

This conclusion applies to treatment-naive as well as chemotherapy-pretreated CLL. Defects in the p53 regulatory network, including defects in p53-induced apoptotic effector molecules, do not appear to play a significant role in CLL response to MDM2 inhibition.53-58 This is in concordance with 3 previous reports of pilot studies.55,59,60 MDM2 inhibitors therefore potentially offer efficacious cancer cell killing for the majority of patients with CLL with high-risk or relapsed disease.

Our integrated genomic profiling analysis of chromosome arm 17p together with p53 sequence data and p53 immunoblotting supports the conclusion that all del17p cases (by FISH) have aberrant p53 function; given that 4 cases of p53 mutants/absent expression without del17p were identified (including 2 cases with copy-neutral LOH at 17p and homozygous p53 mutations) that demonstrated resistance to MDM2 inhibition, we conclude that patients with CLL with del17p are resistant to MDM2 inhibition secondary to associated p53 abnormalities. Therefore, the clinically important del17p subgroup of patients with CLL, which is in need of new therapies, is unlikely to benefit from MDM2 inhibitor therapy.

These data also support the routine clinical use of p53 immunoblotting on purified CLL cells before and after MDM2 inhibitor treatment as an important addition to the current panel of clinically useful biomarkers. Immunoblotting for p53 detected all p53 sequence mutants as well as CLL with p53 expression defects in our study. Importantly, all CLL cases demonstrating aberrant as compared with wild-type p53 induction were relatively resistant to MDM2 inhibitor kill. Finally, CLL cases with aberrant p53 immunoblotting results demonstrated an aggressive disease course.

We also conclude that p53 immunoblotting before and after MDM2 inhibitor treatment more comprehensively interrogates p53 defects than either FISH for del17p or p53 exon resequencing.61

During these studies we identified for the first time a strong correlation between high sensitivity to MDM2 inhibitor cell kill ex vivo and aggressive CLL in cases with wild-type p53 function. This is a novel finding and of potentially significant clinical importance, as these patients with an early need for therapy may benefit from MDM2 inhibitor therapy.

As previously reported in a small patient sampling, ZAP-70 expression or monoallelic ATM loss did not affect MDM2 inhibitor susceptibility.59 We confirm and extend this observation using our larger patient cohort. Furthermore, we report that the mutation status of the IgVH genes does not predict MDM2 inhibitor mediated cell kill in CLL.

It is important to note that we attempted to detect residual effects of these biomarkers (ZAP-70 and IgVH) on MDM2 inhibitor sensitivity by excluding patients with p53 abnormalities. In clinical practice, however, p53 status is not comprehensively analyzed and therefore routinely confounds the effect of these markers on various clinical outcome parameters.

In summary, our study provides clinically relevant data in the context of planned clinical trials with MDM2 inhibitors that allows stratification of patients with CLL into 2 groups: those with and those without p53 defects. Early-phase trials of MDM2 inhibitors in CLL therefore should incorporate pretrial in vitro measurements of p53 induction in response to MDM2 inhibition on patient specimens into the clinical trial schema.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America Special Fellow Award (S.M.), a Leukemia Research Foundation New Investigator Award (S.M.), the National Institutes of Health (NIH; 1 R21 CA124420-01A1; S.M.), NIH through the University of Michigan's Cancer Center Support Grant (5 P30 CA46592), and a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Translational Research Grant (S.W. and S.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.S., P.O., and S.M. performed the laboratory research and wrote the paper; H.E., M.K., M.T., L.K., and S.M. enrolled patients and contributed and analyzed clinical data; K.S. assisted with statistical analysis; S.S. and S.W. provided the MDM2 inhibitors; S.M., S.S., and S.W. conceived the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.W. is a shareholder and founder of Ascenta Therapeutics. He is a consultant to Ascenta Therapeutics and the principal investigator of a research contract between Ascenta Therapeutics and the University of Michigan. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sami N. Malek, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Hematology and Oncology, University of Michigan, 1500 E Medical Center Dr, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0936; e-mail: smalek@med.umich.edu.