Abstract

PML-RARα is the causative oncogene in 5% to 10% of the cases of acute myeloid leukemia. At physiological concentrations of retinoic acid, PML-RARα silences RARα target genes, blocking differentiation of the cells. At high concentrations of ligand, it (re)activates the transcription of target genes, forcing terminal differentiation. The study of RARα target genes that mediate this differentiation has identified several genes that are important for proliferation and differentiation control in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. In this paper, we show that the PML-RARα fusion protein not only interferes with the transcription of regular RARα target genes. We show that the ID1 and ID2 promoters are activated by PML-RARα but, unexpectedly, not by wild-type RARα/RXR. Our data support a model in which the PML-RARα fusion protein regulates a novel class of target genes by interaction with the Sp1 and NF-Y transcription factors, without directly binding to the DNA, defining a gain-of-function for the oncoprotein.

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is characterized by an excess of immature promyelocytes in the bone marrow that fail to differentiate toward mature granulocytes. In approximately 98% of the cases, the retinoic acid receptor-α (RARα) gene is fused to the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene resulting in a PML-RARα fusion protein. The PML-RARα chimeric protein contains most of the PML sequence and a large part of RARα, including its DNA- and nuclear hormone–binding domains. APL blasts can be forced to terminally differentiate using pharmacological doses of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA). When treated with chemotherapy, APL patients can be cured in approximately 40% of the cases. The combination of ATRA with chemotherapy leads to a remarkably high cure rate of approximately 90%,1,2 and APL currently represents the best prognostic group among the different forms of leukemia. This treatment constitutes one of the first examples of successful induction of differentiation of malignant cells yielding significant clinical results.

The role of PML-RARα in transformation and terminal differentiation has been studied intensively in the past decade. PML-RARα was shown to act as a dominant oncogene, interfering with the normal function of the unrearranged PML as well as the unrearranged RARα protein. Expression of the fusion protein in immature hematopoietic cells induced a maturation block at the promyelocytic stage. Inoculation of PML-RARα–transduced bone marrow cells into irradiated syngenic mice resulted in the development of retinoic acid–sensitive leukemia.3,4 Furthermore, PML-RARα transgenic mice developed a myeloproliferative syndrome that progressed to overt leukemia in 30% to 90% of the animals after 6 to 12 months, depending on the promoter that was used.5-7

PML is a ubiquitously expressed protein that localizes to nuclear substructures termed nuclear bodies. More than 50 protein partners with various biologic functions colocalize with PML.8 In APL cells, these nuclear bodies are disrupted and dispersed into numerous small microspeckles.9 PML has multiple tumor-suppressor functions and is involved in growth control, replicative senescence, and apoptosis.10 PML−/− mice are prone to develop tumors in response to various forms of stress. In addition, PML-RARα transgenic mice develop leukemia much faster in a PML−/− background.11

Retinoic acid receptors are transcription factors that activate genes in a ligand-dependent manner. RARα binds to DNA as a heterodimer with RXR proteins. In the absence of ligand, both RARα/RXR and PML-RARα bind corepressors such as N-Cor and SMRT and recruit histone deacetylases leading to gene silencing. In the presence of ligand, the corepressors are replaced by coactivators, leading to transcriptional activation. However, PML-RARα releases the corepressors at much higher concentrations of ligand compared with the unrearranged receptors. Since PML-RARα competes with unrearranged receptors for the same DNA-binding sites, the presence of the fusion protein results in dominant silencing of retinoic acid receptor target genes at physiological concentrations of ligand. At higher, supraphysiological concentrations the fusion protein can still function as a transcriptional activator releasing the corepressor complex and allowing the transcription of genes that are important for granulocytic differentiation.12-15 The release of the differentiation block by high concentrations of retinoic acid leads to terminal granulocytic differentiation of the leukemic cells and the induction of hematologic remissions in the patients. RARα target genes are not restricted to genes that contain a consensus retinoic acid receptor–binding site in their promoter. Liganded RARα is able to repress AP-1–mediated transcription.16-18 PML-RARα abnormally regulates AP-1 activity as it stimulates AP-1–dependent transcription in the presence of ligand, whereas unliganded PML-RARα inhibits AP-1–dependent transcription.19 In addition, RARα may interfere with GATA-2–dependent transcription. Liganded RARα enhances GATA-2–dependent gene transcription via direct protein-protein interaction.20 This activity is retained in the PML-RARα fusion protein.21 Furthermore, interaction of normal retinoid receptors with the transcription factor Sp1 has been shown.22,23 Together, the data support a model in which PML-RARα interferes with RARα target gene expression in a dominant fashion, and that restoration of target gene expression by high concentrations of ligand is important for the induction of differentiation.

Apart from interference with the function of both parental proteins in a dominant-negative manner, a gain-of-function for PML-RARα is suggested by various observations. PML-RARα may bind to DNA as a heterodimer with RXR, but also independently from RXR as a homodimer.24 It may bind to regular retinoic acid receptor–binding sites consisting of a repeated consensus ((A/G)G(T/G)TCA) sequence, but the required spacing between the 2 half-sites is less stringent for the fusion protein. This allows the fusion protein to bind to a wider range of DNA-target sequences compared with normal receptors.25,26 The importance of PML-RARα as a transcriptional activator of differentiation-inducing genes was shown by in vitro experiments. Expression of PML-RARα in the myeloid cell line U937 (that also expresses normal retinoic acid receptors) enhanced their sensitivity to the induction of differentiation by ATRA.27 In addition, forced expression of PML-RARα, but not RARα, in an ATRA-resistant APL cell line with constitutive degradation of the chimeric protein restored ATRA sensitivity.28 Importantly, in APL patients who became resistant to differentiation induction with ATRA during therapy, additional mutations were found in the ligand-binding domain of the RARα part of the PML-RARα fusion protein, indicating an important role for the fusion protein during the retinoic acid–induced differentiation of the leukemic cells.29 Finally, experimental mouse models in which various natural and artificial RARα fusion proteins were expressed also support a model in which interference with the function of RARα and PML is important, but in addition, they suggest that the PML-RARα fusion protein exhibits gain-of function characteristics, unique to the fusion protein.7,30 So far, the mechanisms behind these observations remain largely unclear.

We have previously shown that the transcription factor inhibitors ID1 and ID2 are up-regulated upon treatment with ATRA and play a role in cell cycle arrest during APL differentiation.31 In this study, we investigated the mechanism by which these genes are regulated in APL cells. We found that ID1 and ID2 are regulated by PML-RARα through a novel mechanism, which is not shared with normal RARα, defining an as-yet-unrecognized class of retinoic acid–induced genes in APL.

Methods

Cell culture

NB4, U937, and U937-PR9 cells (kindly provided by Dr P. G. Pelicci and Dr F. Grignani) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD); Hep3b cells, in IMDM (Gibco); and HEK293 cells, in DMEM + 2 mM l-glutamine. Media were supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco). ATRA was used at a final concentration of 10−6 M (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and ZnSO4, at 100 μM. Cycloheximide (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA) was added 30 minutes prior to ATRA at 4 μg/mL.

DNA constructs and antibodies

The human ID1 promoter was obtained from J. Campisi (University of California, Berkeley). The ID2 promoter32 was cloned into the XhoI-HindIII sites of the pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Madison WI) after amplification with the following primers: sense 5′-GTACGGTACCTCGAGTTGGGCATGGTTTGCAATA-3′ and antisense 5′-GTACAGATCTAAGCTTGAAGCCCGAGCCCGGC-3′. RARE3-tk-luc,33 PML-RARαΔR,34 and PML-RARαΔCC, PML-RARα, RARα, and RXR expression constructs25 were as described. FLAG-PML-RARα was from A. Tomita35 and was recloned into a cytomegalovirus (CMV) expression vector. ID1 promoter deletion/mutation fragments were constructed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cloned into the XhoI-HindIII sides of PGL3-basic (Promega). All constructs were sequence verified. The dominant-negative NF-YA (YAm29) construct and anti–NF-YB polyclonal antiserum were from R. Mantovani (University of Milan, Milan, Italy). pGEX-Sp1 was from H. Rotheneder (University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria). Anti-Sp1 (PEP-2), anti–NF-YA (H-209), anti-RARα (C-20), and anti-ID1 (Z-8) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-PML rabbit antibody was as described.9 Anti-FLAG (M2) antibody was from Sigma. As a control in the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments, human IgG was used (Ivegam, Sanquin, The Netherlands)

Northern blotting

Total cellular RNA was isolated by guanidium-isothiocyanate lysis and centrifugation on a 5.7 M cesium chloride cushion. Total RNA (10 μg) was size-fractionated by 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis and transferred onto Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Filters were hybridized at 65°C overnight in phosphate buffer (2N NaH2PO4, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 mM EDTA, pH 8, and 1% BSA). DNA probes were labeled with [32P]α-dATP by random primed labeling (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). After hybridization, filters were washed in 0.2 × SSC/0.2% SDS for 15 minutes at 65°C. Northern blots were hybridized to radiolabeled human ID1 or ID2 probes (kindly provided by Dr S. Stegman). As a control for equal loading, filters were stripped and hybridized to a 777-bp HindIII-EcoRI human GAPDH fragment.

Transactivation studies

Cells were transfected using calcium-phosphate precipitates with 0.25 μg pGL3-ID1 or -ID2 promoter, 0.05 μg nuclear receptor expression vector, 0.1 μg Renilla vector (pRL-CMV; Promega), and 1 μg YAm29 expression vector. The total amount of DNA was normalized to 1.4 μg for all transfections using empty vectors. Cells were harvested 16 hours after ATRA treatment using 100 μL Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega). Firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were measured on a luminometer (Lumat LB 9507; Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System reagents (Promega).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described,36 and 5 μg was incubated in a total volume of 15 μL containing 1 μg double stranded poly(dI)-poly(dC), 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM KCL, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10% (wt/vol) glycerol, 300 μg/mL BSA, and 0.5 ng of a labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probe: ID1 5′-CCGCCCATTGGCTGCTTTTGAACGT. To show specificity of binding, nonlabeled 100-fold excess of double-stranded oligonucleotides was added to compete for binding with the labeled probe. For this, either the ID1 probe (self-competition), a sequence not containing any CCAAT box (5′-TCAGAGTTCAAGGTTCTAGTCGCTGCGGC), or a NF-Y–binding site containing oligonucleotide from the CD10 gene (5′-ATCCCGACCAATGAGCGCACGGGGCCGGGT) was used.37 DNA-Protein complexes were resolved on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5 × TBE buffer.

GST pull-down

GST fusion proteins were produced in E coli BL21 which were induced at A600 = 0.5 with 300 μM IPTG for 4 hours. Proteins were released by sonication and loaded onto glutathione-agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) by incubation at 4°C for 2 hours in lysis buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.3], 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40, and protease inhibitors). Pull-down was performed using in vitro–translated PML-RARα and PML-RARαΔcc (reticulocyte lysate; Promega) or rHSp1 (Promega), by 2-hour incubation at 4°C. Beads were washed in lysis buffer and subsequently resuspended in SDS-loading buffer.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

DNA-protein cross-linking was done for 30 minutes at room temperature by adding formaldehyde at a final concentration of 1% directly to the culture medium. Cross-linking was stopped by the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM. Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, buffer B (10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.25% Triton X-100, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6]), and buffer C (1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.15 M NaCl, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.6]) and resuspended in incubation buffer (0.15% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6] and protease inhibitors) at 33 × 106 cells/mL. Chromatin was sonicated using the Bioruptor (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan), at high intensity for 15 minutes with 0.5-minute intervals. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 4°C for 15 minutes. Supernatant (120 μL) was incubated with 30 μL precoated protein A/G plus agarose beads 50% vol/vol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 0.1% BSA, 36 μL 5 × incubation buffer, protease inhibitors and 2 to 5 μg antibody (anti–NF-YA, anti-PML, anti-FLAG, or nonspecific IgG from human serum) and rocked at 4°C for 16 hours. Beads were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with buffer 1 (0.1% SDS, 0.1% NaDOC, 1% Triton X-100, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6]), once with buffer 2 (0.1% SDS, 0.1% NaDOC, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6]), once with buffer 3 (0.25 M LiCL, 0.5% NaDOC, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6]), and twice with buffer 4 (1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6]). Chromatin antibody complexes were eluted by the addition of 1% SDS and 0.1 M NaHCO3 to the pellet and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cross-linking was reversed by the addition of NaCl (0.44 M final concentration) and incubation of the eluted samples for at least 4 hours at 65°C. DNA was recovered by phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol extraction followed by chloroform-isoamylalcohol extraction and precipitated by the addition of 0.1 volume of 1 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and 2.5 volumes of ethanol. Precipitated DNA was dissolved in water, and input as well as immunoprecipitated DNA were analyzed using quantitative PCR for genomic sequences from the ID1, ID2, RARβ, and p21 promoter regions.38

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR to measure ID1 and ID2 mRNA expression was performed with the ABI/PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection system (ABI/PE). As a reference gene, PBGD was used. The primer/probe sequences for the ID1 gene were as follows: sense 5′-GTTACTCACGCCTCAAGGAGCT, antisense 5′-GAGAATCTCCACCTTGCTCACC, and probe FAM 5′-CCCACCCTGCCCCAGAACCG; for ID2: sense 5′-GACTGCTACTCCAAGCTCAAGGA, antisense 5′-CGTGCTGCAGGATTTCCAT, and probe FAM 5′-CCCAGCATCCCCCAGAACAAGAAGG. PCRs were done in a 50-μL reaction mixture (1.25 U AmpliTaq Gold, 1 × buffer A [both ABI/PE], 250 mM dNTPs [Pharmacia], and 5 mM MgCl2) for 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 1 minute at 62°C. Quantitative PCR following ChIP was done using Sybr Green PCR (ABI/PE). Primer sequences for the ID1 promoter were as follows; sense 5′-CACTGCGAGCAGGCACTAGAC and antisense 5′-AGCCACAGCTTGTCTTT; for the ID2 promoter: sense 5′-CTGTACTCTATTTACCACCCCAGCTG and antisense 5′-GGCGTGGGCTTGGTTCTT; for the RARβ promoter: sense 5′-TTGGGTCATTTGAAGGTTAGCA and antisense 5′-CACACAGAATGAAAGATTGAATTGC; for the p21 gene, sense 5′-GGCGGGGCGGTTGTAT and antisense 5′-AAGGAACTGACTTCGGCAGC.

Results

ID1 and ID2 are direct retinoic acid–responsive genes in APL cells

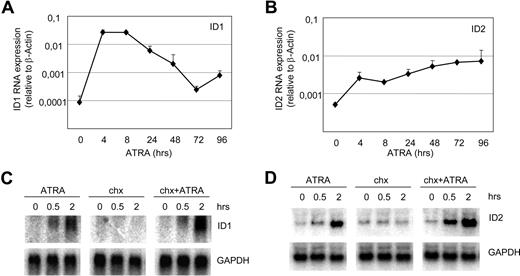

Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors and their inhibitors, ID proteins, play crucial roles in the regulation of differentiation in various cell types. We have shown that ID1 and ID2 are up-regulated in APL cells upon exposure to ATRA.31 Up-regulation of ID1 and ID2 mRNA was confirmed with qPCR (Figure 1A,B), showing clear up-regulation within 4 hours after the addition of ATRA. To investigate whether ID1 and ID2 were directly up-regulated by ATRA, cells were treated with cycloheximide prior to the addition of ATRA to inhibit protein translation. Both ID1 and ID2 mRNAs were up-regulated within 0.5 hours by ATRA, regardless of the addition of cycloheximide (Figure 1C,D). This indicates that both genes were directly up-regulated, without intermediate protein production.

ID1 and ID2 are direct retinoic acid target genes in NB4 cells. Quantitative PCR and Northern blot analysis of NB4 cells treated with ATRA. mRNA was isolated from NB4 cells and ID1 (A) and ID2 (B) expression was determined using specific primers and probes by quantitative PCR (n = 4). Quantities were normalized based on β-actin expression. To investigate whether the induction of ID1 and ID2 was dependent on intermediate protein production, cells were treated with cycloheximide alone (4 μg/mL) or with the combination of cycloheximide and ATRA (10−6 M). Blots were hybridized using radiolabeled ID1-specific (C) and ID2-specific (D) probes. As a control for equal loading, blots were stripped and rehybridized with GAPDH-specific probes.

ID1 and ID2 are direct retinoic acid target genes in NB4 cells. Quantitative PCR and Northern blot analysis of NB4 cells treated with ATRA. mRNA was isolated from NB4 cells and ID1 (A) and ID2 (B) expression was determined using specific primers and probes by quantitative PCR (n = 4). Quantities were normalized based on β-actin expression. To investigate whether the induction of ID1 and ID2 was dependent on intermediate protein production, cells were treated with cycloheximide alone (4 μg/mL) or with the combination of cycloheximide and ATRA (10−6 M). Blots were hybridized using radiolabeled ID1-specific (C) and ID2-specific (D) probes. As a control for equal loading, blots were stripped and rehybridized with GAPDH-specific probes.

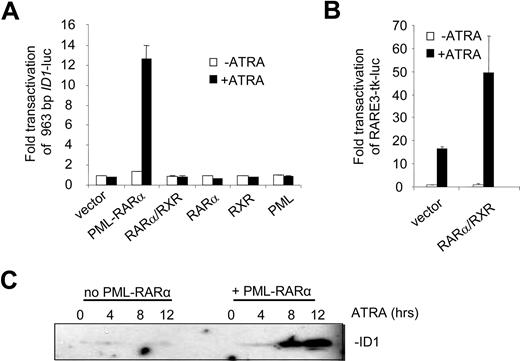

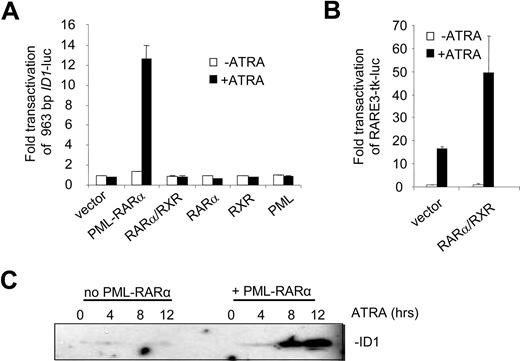

The ID1 upstream promoter is transactivated by PML-RARα but not by RARα/RXR

To identify the regulatory DNA sequences through which the induction of ID1 by retinoic acid was mediated, we analyzed the 5′ upstream promoter sequence in transactivation assays. A 963-bp fragment of the promoter, including the putative TATA box, was cloned into a luciferase reporter construct. When expressed alone, RARα, RXR, and PML were not able to transactivate the ID1 promoter both in the absence and presence of ATRA (Figure 2A). In contrast, PML-RARα transactivated the promoter more than 12-fold in an ATRA-dependent fashion. Surprisingly, the combination of RARα/RXR did not transactivate the promoter, both in the absence and presence of ATRA. To verify that RARα and RXR were expressed and functional, a control luciferase construct was used containing 3 bona fide RAREs from the RARβ promoter (RARE3-tk-luc39 ). This construct was strongly transactivated in the presence of ATRA through endogenous retinoic acid receptors (Figure 2B left bars). This was further enhanced when RARα and RXR were cotransfected (Figure 2B right bars). Together this shows that PML-RARα may regulate ID1 expression through the upstream 963-bp promoter, whereas RARα/RXR cannot.

The ID1 promoter is transactivated by PML-RARα but not by RARα/RXR. (A) Hep3B cells were transfected with the 963-bp ID1 promoter-luciferase reporter construct (ID1-luc) together with a control vector expressing Renilla luciferase. In addition, vectors coding for the various proteins indicated in the figure were transfected. Transactivation is expressed as arbitrary units and is corrected for transfection efficiency measured by Renilla luciferase. Background luminescence of the cells transfected with only the reporter construct without nuclear receptors and in the absence of ATRA was set at 1. Cells were cultured for 16 hours without (▭) and with ( ) ATRA. Mean values and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) To show transactivation by unrearranged retinoic acid receptors, cells were transfected with the RARE3-tk-luc vector, containing 3 bona fide RAREs. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) ID1 expression is increased by PML-RARα in the presence of ATRA. The zinc-inducible PML-RARα cell line U937-PR9 was grown in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of zinc for 16 hours. Cells were treated with ATRA and harvested at the indicated time points. Proteins were size-fractionated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Immunostaining was done with anti-ID1 antibody.

) ATRA. Mean values and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) To show transactivation by unrearranged retinoic acid receptors, cells were transfected with the RARE3-tk-luc vector, containing 3 bona fide RAREs. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) ID1 expression is increased by PML-RARα in the presence of ATRA. The zinc-inducible PML-RARα cell line U937-PR9 was grown in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of zinc for 16 hours. Cells were treated with ATRA and harvested at the indicated time points. Proteins were size-fractionated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Immunostaining was done with anti-ID1 antibody.

The ID1 promoter is transactivated by PML-RARα but not by RARα/RXR. (A) Hep3B cells were transfected with the 963-bp ID1 promoter-luciferase reporter construct (ID1-luc) together with a control vector expressing Renilla luciferase. In addition, vectors coding for the various proteins indicated in the figure were transfected. Transactivation is expressed as arbitrary units and is corrected for transfection efficiency measured by Renilla luciferase. Background luminescence of the cells transfected with only the reporter construct without nuclear receptors and in the absence of ATRA was set at 1. Cells were cultured for 16 hours without (▭) and with ( ) ATRA. Mean values and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) To show transactivation by unrearranged retinoic acid receptors, cells were transfected with the RARE3-tk-luc vector, containing 3 bona fide RAREs. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) ID1 expression is increased by PML-RARα in the presence of ATRA. The zinc-inducible PML-RARα cell line U937-PR9 was grown in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of zinc for 16 hours. Cells were treated with ATRA and harvested at the indicated time points. Proteins were size-fractionated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Immunostaining was done with anti-ID1 antibody.

) ATRA. Mean values and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) To show transactivation by unrearranged retinoic acid receptors, cells were transfected with the RARE3-tk-luc vector, containing 3 bona fide RAREs. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) ID1 expression is increased by PML-RARα in the presence of ATRA. The zinc-inducible PML-RARα cell line U937-PR9 was grown in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of zinc for 16 hours. Cells were treated with ATRA and harvested at the indicated time points. Proteins were size-fractionated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Immunostaining was done with anti-ID1 antibody.

To test whether PML-RARα expression would result in ATRA-dependent induction of the endogenous ID1 gene, we used the U937-PR9 cell line that is stably transfected with a Zn2+-inducible PML-RARα expression cassette.34 In PML-RARα–expressing U937 cells, ATRA strongly induced ID1 expression (Figure 2C right panel), in contrast to U937 cells that did not express PML-RARα (Figure 2C left panel).

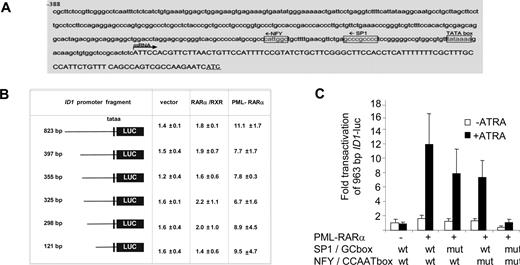

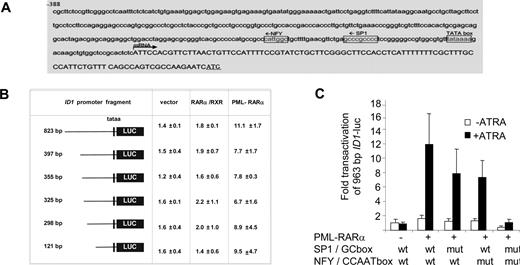

Transactivation of the ID1 promoter is dependent on GC and CCAAT box motifs

To determine the DNA sequences that are relevant for the observed PML-RARα–dependent transactivation, we analyzed the 963-bp upstream promoter construct of the ID1 gene further. The consensus RAR/RXR-binding sequence (RARE) consists of a repeated (A/G)G(T/G)TCA sequence that is separated by 2 or 5 base pairs. However, in the 963-bp ID1 promoter, no consensus RARE was found. As PML-RARα may bind to a much wider variety of DNA sequences,25,26 we made luciferase constructs with different promoter truncations. All the truncation mutants could still be transactivated by PML-RARα (Figure 3B), including the smallest, 121-bp promoter construct. This construct does not contain any sequence that even remotely resembles a retinoic acid receptor–binding site (Figure 3A). Analysis of the 121-bp promoter sequence for putative binding sites for other transcription factors showed a perfect consensus-binding site for the transcription factors NF-Y (CCAAT box) and Sp1 (GC box). To test their relevance, we mutated these sites individually and in combination in the context of the 963-bp promoter fragment. Mutation of the GC box or the CCAAT box alone partially impaired transactivation by PML-RARα, while deletion of the GC box and the CCAAT box in combination almost completely abolished transactivation (Figure 3C; raw Renilla and Firefly luciferase data are given in Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). This indicated that transactivation of the ID1 promoter by PML-RARα was dependent on the GC and CCAAT motifs.

The CCAAT and GC box in the ID1 promoter are required for PML-RARα–mediated transactivation. (A) ID1 promoter region showing the presence of consensus Sp1- and NF-Y–binding sites. (B) Transactivation of ID1 promoter-luciferase constructs. Several deletion constructs were generated and transfected in combination with RARα plus RXR, or with PML-RARα. Transactivation assays were performed as described in Figure 2. Mean values from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) To investigate the importance of the putative Sp1- and NF-Y–binding sites in the − 121-bp upstream promoter sequence of the ID1 gene for transactivation by PML-RARα, these sites were mutated in the context of the − 963-bp promoter fragment. Mutations were introduced either alone, or in combination. Transactivation by PML-RARα was performed as described in Figure 1. Sequences were mutated as follows: GC box: CCGCCC was replaced by CTATCC; NF-Y site: ATTGG was replaced by ACACG. Transactivation was significantly lower in the promoter fragments with one mutated binding site in comparison with the wt promoter fragment (P < .01).

The CCAAT and GC box in the ID1 promoter are required for PML-RARα–mediated transactivation. (A) ID1 promoter region showing the presence of consensus Sp1- and NF-Y–binding sites. (B) Transactivation of ID1 promoter-luciferase constructs. Several deletion constructs were generated and transfected in combination with RARα plus RXR, or with PML-RARα. Transactivation assays were performed as described in Figure 2. Mean values from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) To investigate the importance of the putative Sp1- and NF-Y–binding sites in the − 121-bp upstream promoter sequence of the ID1 gene for transactivation by PML-RARα, these sites were mutated in the context of the − 963-bp promoter fragment. Mutations were introduced either alone, or in combination. Transactivation by PML-RARα was performed as described in Figure 1. Sequences were mutated as follows: GC box: CCGCCC was replaced by CTATCC; NF-Y site: ATTGG was replaced by ACACG. Transactivation was significantly lower in the promoter fragments with one mutated binding site in comparison with the wt promoter fragment (P < .01).

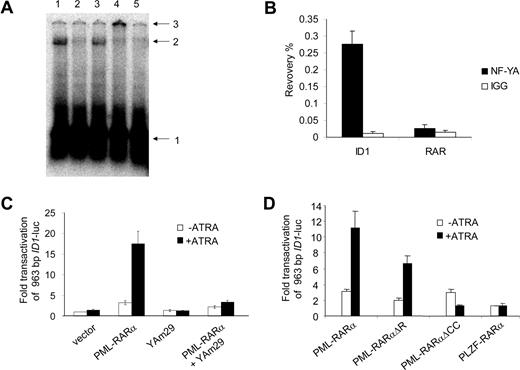

Functional NF-Y is necessary for transactivation of the ID1 promoter by PML-RARα

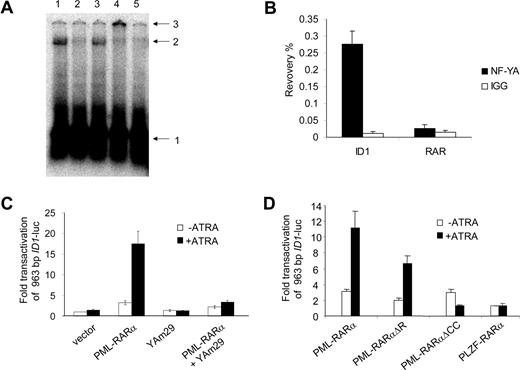

Sp1 and NF-Y are ubiquitously expressed transcription factors. NF-Y is a trimeric protein complex consisting of the subunits NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC. All 3 subunits are necessary for the complex to bind to the DNA.40 Using real-time PCR, we confirmed that Sp1 and all 3 NF-Y subunits were expressed in primary APL cells (Figure S2). Binding of Sp1 to the promoter of ID1 was shown previously.41 Therefore, we tested whether NF-Y was able to bind to the CCAAT site from the ID1 promoter. Incubation of a radioactively labeled DNA probe containing the CCAAT box with cellular protein extracts resulted in a clear shifted complex (Figure 4A lane 1). This shift was competed by a 100-fold excess of nonlabeled probe (Figure 4A lane 2) and by an excess of an oligo containing the NF-Y–binding site of the CD10 promoter (Figure 4 lane 542 ), but not by an excess of probe lacking a NF-Y–binding site (Figure 4A lane 3). When anti–NF-YB antiserum was added (Figure 4A lane 4) the protein-DNA complex was supershifted, identifying the DNA-binding protein complex as NF-Y. To further test whether NF-Y is present on the endogenous ID1 promoter, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. Using anti–NF-YA antibody, recovery of the ID1 promoter sequences from U937 cells was more than 70 times higher than recovery with nonspecific IgGs (Figure 4B right bars). In the same experiment, no enrichment was seen for the RARβ promoter (Figure 4B left bars), indicating that NF-Y is present on the endogenous ID1 promoter but not on the RARβ promoter.

NF-Y binds to the CCAAT box element from the ID1 promoter and is required for PML-RARα–mediated transactivation. (A) EMSA showing binding of NF-Y to the putative NF-Y–binding site from the ID1 promoter. Hep3B nuclear extracts were incubated with a labeled DNA probe containing the NF-Y box from the ID1 promoter region. A clearly shifted protein-DNA complex was seen (lane 1). Competition experiments were done with 100 × cold ID1 probe (lane 2) and with an unlabeled probe containing the confirmed NF-Y–binding site from the CD10 gene promoter (lane 5). In addition, a sequence without any recognizable NF-Y–binding site was used for competition (lane 3). Addition of anti–NF-YB antibody shifted the complex to a higher molecular weight complex (lane 4). Arrows indicate free probe (1), shifted DNA-protein complex (2), and the supershifted DNA-protein-antibody complex (3). (B) To detect DNA-binding of NF-Y in intact cells, ChIP assays were performed using anti–NF-YA antibodies. As a control, the nonspecific IgG fraction from human serum was used. The y-axis shows the recovery (%) of ID1 or RARβ sequences relative to the input. In U937 cells, NF-Y clearly bound to the ID1 promoter (right bars), but not to the RARβ gene (left bars). Mean values from 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown. (C) To further show the importance of NF-Y for the PML-RARα–mediated transcriptional activation of ID1, transfections (as described in Figure 2) were performed using the dominant-negative NF-YA subunit (Yam29) and the 963 ID1 promoter construct. In the presence of YAm29, PML-RARα–mediated transcription was severely diminished (right bars). (D) To investigate the importance of different domains of PML-RARα, vectors encoding the DNA-binding–defective PML-RARαΔR mutant, and a mutant lacking the coiled-coil protein-protein interaction domain of PML (PML-RARαΔCC), were used. In addition, a PLZF-RARα expression construct was used. Transfections were performed as in Figure 2 using the 963 ID1 promoter construct; mean values of 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown.

NF-Y binds to the CCAAT box element from the ID1 promoter and is required for PML-RARα–mediated transactivation. (A) EMSA showing binding of NF-Y to the putative NF-Y–binding site from the ID1 promoter. Hep3B nuclear extracts were incubated with a labeled DNA probe containing the NF-Y box from the ID1 promoter region. A clearly shifted protein-DNA complex was seen (lane 1). Competition experiments were done with 100 × cold ID1 probe (lane 2) and with an unlabeled probe containing the confirmed NF-Y–binding site from the CD10 gene promoter (lane 5). In addition, a sequence without any recognizable NF-Y–binding site was used for competition (lane 3). Addition of anti–NF-YB antibody shifted the complex to a higher molecular weight complex (lane 4). Arrows indicate free probe (1), shifted DNA-protein complex (2), and the supershifted DNA-protein-antibody complex (3). (B) To detect DNA-binding of NF-Y in intact cells, ChIP assays were performed using anti–NF-YA antibodies. As a control, the nonspecific IgG fraction from human serum was used. The y-axis shows the recovery (%) of ID1 or RARβ sequences relative to the input. In U937 cells, NF-Y clearly bound to the ID1 promoter (right bars), but not to the RARβ gene (left bars). Mean values from 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown. (C) To further show the importance of NF-Y for the PML-RARα–mediated transcriptional activation of ID1, transfections (as described in Figure 2) were performed using the dominant-negative NF-YA subunit (Yam29) and the 963 ID1 promoter construct. In the presence of YAm29, PML-RARα–mediated transcription was severely diminished (right bars). (D) To investigate the importance of different domains of PML-RARα, vectors encoding the DNA-binding–defective PML-RARαΔR mutant, and a mutant lacking the coiled-coil protein-protein interaction domain of PML (PML-RARαΔCC), were used. In addition, a PLZF-RARα expression construct was used. Transfections were performed as in Figure 2 using the 963 ID1 promoter construct; mean values of 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown.

A dominant-negative form of NF-YA has been described (YAm29).43 This mutated NF-YA subunit can still bind to the NF-YB and NF-YC subunits, but is not able to bind to DNA, preventing the formation of a functional trimeric NF-Y complex. To investigate whether functional NF-Y was necessary for the transactivation of ID1, the YAm29 mutant was tested in a transactivation assay. Transactivation of ID1 by PML-RARα upon ATRA treatment was severely decreased in the presence of dominant-negative NF-YA (Figure 4C). This effect was promoter specific as YAm29 did not influence transactivation of the RARβ promoter construct (RARE3-tk-luc) by PML-RARα or RARα/RXR (data not shown).

Up-regulation of ID1 is dependent on PML-RARα but does not require the DNA-binding domain of the fusion protein

To test whether PML-RARα might transactivate the ID1 promoter without directly binding to the DNA, we used a PML-RARα construct from which the DNA-binding domain was deleted (PML-RAR/ΔR,34 ). PML-RAR/ΔR has been shown to be unable to transactivate a promoter containing a bona fide RARE. In contrast, PML-RAR/ΔR retained the ability to transactivate the ID1 promoter (Figure 4D). Similar results were found when the transactivation assay was repeated in the myeloid cell line HL-60 (Figure S3). This indicated that transactivation of the ID1 promoter by PML-RARα does not require direct binding of PML-RARα to the DNA.

PLZF-RARα is generated by a t(11;17) translocation that is found in approximately 2% of the patients with APL. It contains the same part of the retinoic acid receptor as PML-RARα. Similar to PML-RARα, this fusion protein may form homodimers with DNA-binding capacity.44 Interestingly, PLZF-RARα was not able to transactivate the ID1 promoter, suggesting that the PML part of PML-RARα is necessary for transactivation of the ID1 promoter (Figure 4D). When the coiled-coil domain of PML-RARα was deleted (PML-RAR/ΔCC25,34 ), it was no longer able to transactivate the ID1 promoter (Figure 4D). As this domain is involved in protein-protein interactions, this suggested that PML-RARα homodimerization or interaction of PML-RARα with another protein was necessary for the transactivation of ID1.

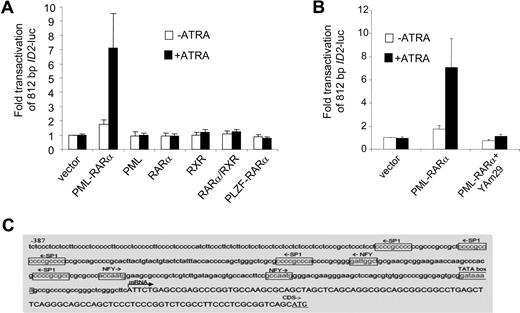

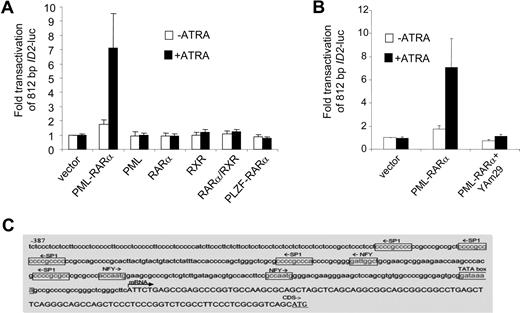

The ID2 promoter is also transactivated by PML-RARα but not by RARα/RXR

To investigate whether ID2 was regulated in a similar manner as ID1, we cloned the upstream promoter of ID2 (812 bp) into a luciferase reporter plasmid. Similar to ID1, no consensus retinoic acid receptor–binding site could be found in the ID2 promoter sequence. Also comparable with ID1, RARα, RXR, PML, PLZF-RARα, and RARα/RXR did not transactivate the ID2 promoter, whereas PML-RARα did (Figure 5A). Furthermore, transactivation of ID2 by PML-RARα was abolished in the presence of dominant-negative NF-YA (Figure 5B). Inspection of the ID2 promoter sequence revealed 3 NF-Y and 5 Sp1 consensus-binding sites (Figure 5C). Together, these data show that like ID1, ID2 may also be transactivated by PML-RARα without direct DNA binding of the fusion protein.

The ID2 promoter is transactivated by PML-RARα but not by RARα/RXR. (A) Cells were transiently transfected with a 812-bp ID2-luciferase reporter construct (ID2-luc). Transfections and controls were as described in Figure 2. Background luminescence of the cells transfected with only a reporter construct (no nuclear receptor and no ATRA) was set at 1. Transactivation was measured after treatment without (□) and with (■) 10−6 M ATRA. Mean values from at least 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown. (B) Dominant-negative NF-Y (Yam29) inhibits the transactivation of the ID2 promoter construct by PML-RARα. Transfections were done as described in Figure 2; mean values of 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown. (C) Promoter region of the ID2 gene with putative Sp1- and NF-Y–binding sites.

The ID2 promoter is transactivated by PML-RARα but not by RARα/RXR. (A) Cells were transiently transfected with a 812-bp ID2-luciferase reporter construct (ID2-luc). Transfections and controls were as described in Figure 2. Background luminescence of the cells transfected with only a reporter construct (no nuclear receptor and no ATRA) was set at 1. Transactivation was measured after treatment without (□) and with (■) 10−6 M ATRA. Mean values from at least 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown. (B) Dominant-negative NF-Y (Yam29) inhibits the transactivation of the ID2 promoter construct by PML-RARα. Transfections were done as described in Figure 2; mean values of 3 independent experiments plus or minus SD are shown. (C) Promoter region of the ID2 gene with putative Sp1- and NF-Y–binding sites.

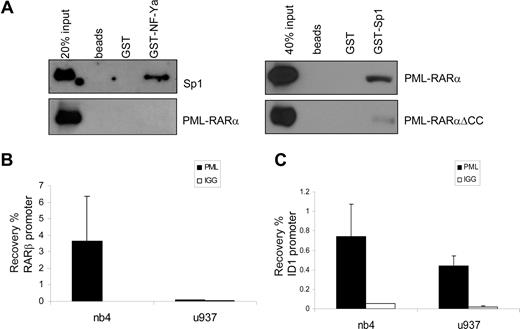

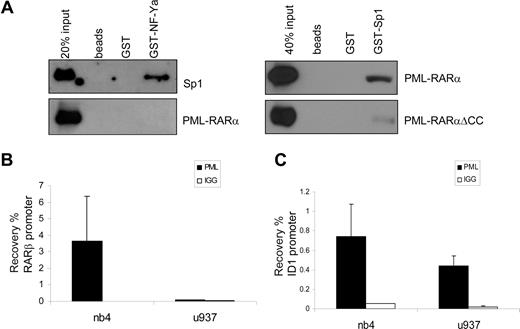

PML-RARα directly interacts with Sp1

NF-Y and Sp1 have been shown to work in concert on many promoters. Direct physical interaction between Sp1 and NF-YA has been shown, indicating that these proteins may bind to adjacent DNA-binding sites and form a complex that regulates transcription.45 We investigated whether PML-RARα could physically interact with Sp1 or NF-YA. GST-tagged, bacterially produced NF-YA and Sp1 proteins were made, as well as in vitro–translated (reticulocyte lysate) PML-RARα for GST pull-down experiments. rhSp1 was commercially available. Whereas a clear interaction was observed between GST-NF-YA and recombinant Sp1 (Figure 6A), in none of the conditions tested could we show a direct interaction between NF-YA and PML-RARα. In contrast, an interaction between PML-RARα and Sp1 was readily observed, whereas no interaction was seen with nonloaded or GST-loaded beads (Figure 6A). GST-Sp1 was also able to capture PML-RAR/ΔCC, although with a much lower efficiency than PML-RARα. This suggests that the binding of PML-RARα is partly through the coiled-coil region and partly through the RARα part of the fusion protein. This is in agreement with earlier publications that have shown binding of both PML and RARα to Sp1.22,46

PML-RARα binds Sp1 and binds to the endogenous ID1 promoter. (A) To test binding of PML-RARα to Sp1 and NF-Y, GST pull-down experiments were performed. Empty beads and beads loaded with GST or GST-NF-YA (left panels) were incubated with in vitro–translated Sp1 (positive control) or in vitro–translated PML-RARα. GST-Sp1 (right panels) was incubated with in vitro–translated PML-RARα or PML-RARαΔCC. Beads were washed and subsequently resuspended in loading buffer. Protein was resolved on SDS-PAGE. Immunostaining was performed with anti-Sp1 or anti-RARα antibody. Clear interactions between NF-YA and Sp1 and between PML-RARα and Sp1 were observed. To show binding of PML-RARα to the endogenous RARβ (B) and ID1 (C) genes, ChIP assays were performed in PML-RARα–positive NB4 cells and in PML-RARα–negative U937 cells. Cells were treated with ATRA for 30 minutes. ChIP was done with anti-PML antiserum. As a control, the nonspecific IgG fraction from human serum was used. The Y-axis shows the recovery (%) of ID1 or RARβ sequences relative to the input. Mean values plus or minus SD of 4 independent experiments are shown.

PML-RARα binds Sp1 and binds to the endogenous ID1 promoter. (A) To test binding of PML-RARα to Sp1 and NF-Y, GST pull-down experiments were performed. Empty beads and beads loaded with GST or GST-NF-YA (left panels) were incubated with in vitro–translated Sp1 (positive control) or in vitro–translated PML-RARα. GST-Sp1 (right panels) was incubated with in vitro–translated PML-RARα or PML-RARαΔCC. Beads were washed and subsequently resuspended in loading buffer. Protein was resolved on SDS-PAGE. Immunostaining was performed with anti-Sp1 or anti-RARα antibody. Clear interactions between NF-YA and Sp1 and between PML-RARα and Sp1 were observed. To show binding of PML-RARα to the endogenous RARβ (B) and ID1 (C) genes, ChIP assays were performed in PML-RARα–positive NB4 cells and in PML-RARα–negative U937 cells. Cells were treated with ATRA for 30 minutes. ChIP was done with anti-PML antiserum. As a control, the nonspecific IgG fraction from human serum was used. The Y-axis shows the recovery (%) of ID1 or RARβ sequences relative to the input. Mean values plus or minus SD of 4 independent experiments are shown.

PML and PML-RARα are present on the endogenous ID1 promoter

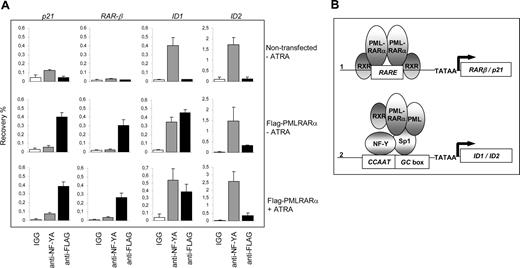

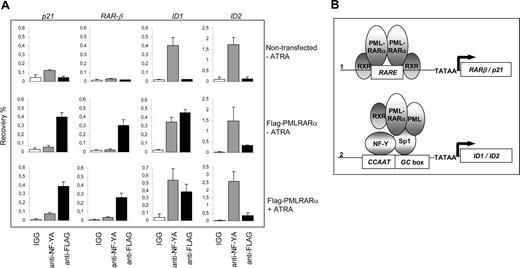

To show the physical interaction of PML-RARα with the endogenous ID1 and ID2 promoters in intact cells, we performed ChIP assays using PML-specific antibodies. The RARβ promoter, which contains a well-defined RARE, served as a positive control. In NB4 cells, we found a clear enrichment for the RARβ promoter (Figure 6B right panel). In contrast, in U937 cells that are PML-RARα negative, no enrichment for the RARβ promoter was seen (Figure 6B left panel), indicating that PML-RARα binds to the RARβ promoter in NB4 cells. The ID1 gene was also precipitated with anti-PML antibody in NB4 cells (Figure 6C right panel). However, this was observed not only in the PML-RARα–positive NB4 cells, but also in the PML-RARα–negative U937 cells (Figure 6C left panel). This indicates that in U937 cells, unrearranged PML protein was present on the ID1 promoter. As the anti-PML does not discriminate between PML and PML-RARα, we could not determine which of these 2 proteins was bound to the ID1 promoter in NB4 cells. To investigate this further, we used a FLAG-tagged PML-RARα expression construct, allowing us to unequivocally identify binding by the PML-RARα fusion protein. HEK-293 cells were transfected with FLAG-PML-RARα (Figure 7A). As a negative control, ChIP was performed using nonspecific IgGs. We compared the presence of (FLAG-tagged) PML-RARα and NF-Y on the 2 classical ATRA target genes RARβ and p21, and on ID1 and ID2. Enrichment of all 4 promoters was found using anti-FLAG antibody, indicating that PML-RARα was bound to these 4 genes in intact cells (Figure 7A, compare top and middle rows). Using anti–NF-Y antibody, enrichment of the ID1 and ID2 promoters was found but no enrichment of RARβ and p21, indicating that NF-Y was present on ID1 and ID2, but not on the 2 classical ATRA target genes RARβ and p21. To determine whether the presence of PML-RARα and NF-Y on the different promoters would be altered by the presence of retinoic acid, ChIP assays were performed in the presence and the absence of ATRA (Figure 7A middle and bottom rows). ATRA did not influence the binding of NF-Y or PML-RARα to these promoters, showing that their binding is ligand independent.

Binding of PML-RARα to the endogenous p21, RAR-β, ID1, and ID2 genes. (A) To show binding of PML-RARα and NF-Y to the endogenous p21, RAR-β, ID1, and ID2 genes, ChIP assays were performed. As anti-PML antibodies do not discriminate between the unrearranged PML protein and the PML-RARα fusion protein, FLAG-tagged PML-RARα was used. Cells were transfected with or without FLAG-PML-RARα and cultured in the presence or absence of 10−6 M ATRA. ChIP was performed using anti-FLAG antibodies, anti–NF-YA antibodies, and control IgGs. The Y-axis shows the recovery (%) of ID1/ID2/p21 or RARβ sequences relative to the input. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) Dominant-negative and gain-of-function model for PML-RARα. Genes that are regulated through a retinoic acid–responsive element (RARE) may be bound by PML-RARα (1). Competition with normal, unrearranged retinoid receptors results in a dominant-negative silencing of the gene by PML-RARα in the absence of ligand. Addition of high-dose retinoic acid may reverse the silencing, allowing transcription. Sp1- and NF-Y–regulated genes may be targeted by PML-RARα through interaction with Sp1 (2). Tethering of PML-RARα to these promoters renders them responsive to retinoic acid, representing a gain-of-function for the PML-RARα fusion protein.

Binding of PML-RARα to the endogenous p21, RAR-β, ID1, and ID2 genes. (A) To show binding of PML-RARα and NF-Y to the endogenous p21, RAR-β, ID1, and ID2 genes, ChIP assays were performed. As anti-PML antibodies do not discriminate between the unrearranged PML protein and the PML-RARα fusion protein, FLAG-tagged PML-RARα was used. Cells were transfected with or without FLAG-PML-RARα and cultured in the presence or absence of 10−6 M ATRA. ChIP was performed using anti-FLAG antibodies, anti–NF-YA antibodies, and control IgGs. The Y-axis shows the recovery (%) of ID1/ID2/p21 or RARβ sequences relative to the input. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) Dominant-negative and gain-of-function model for PML-RARα. Genes that are regulated through a retinoic acid–responsive element (RARE) may be bound by PML-RARα (1). Competition with normal, unrearranged retinoid receptors results in a dominant-negative silencing of the gene by PML-RARα in the absence of ligand. Addition of high-dose retinoic acid may reverse the silencing, allowing transcription. Sp1- and NF-Y–regulated genes may be targeted by PML-RARα through interaction with Sp1 (2). Tethering of PML-RARα to these promoters renders them responsive to retinoic acid, representing a gain-of-function for the PML-RARα fusion protein.

Together, these data show that there are 2 different mechanisms by which PML-RARα may regulate the transcription of target genes (Figure 7B). The first class of target genes consists of genes that contain a retinoic acid response element in their promoter. These genes are normally regulated by unrearranged retinoic acid receptors and may be deregulated by PML-RARα in a dominant-negative manner in the absence of ligand. In the presence of high concentrations of ligand, their expression is restored. The second class of target genes consists of genes that are not normally regulated by retinoic acid receptors. Fusion of the RARα moiety to PML renders these genes responsive to retinoic acid, which defines a novel gain of function for the PML-RARα fusion protein.

Discussion

The successful treatment of APL with high-dose retinoic acid has shown that the differentiation block of the malignant cells can be overcome, leading to terminal differentiation of the leukemic cells and disappearance of the disease. As this is one of the first examples of successful differentiation-induction therapy in cancer, many studies focused on the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the transformation to leukemia, and on the mechanisms that mediate the retinoic acid–induced differentiation of the cells. PML-RARα was shown to interfere with the expression of normal RARα target genes. RARα is an important modulator of granulopoiesis and acts either by direct binding to the DNA, or through interaction with other transcription factors. In this report, we show that PML-RARα interacts with Sp1 and may interfere with the expression of genes that are not normally regulated by retinoic acid receptors. Previously, it was shown that both unrearranged PML46 and unrearranged RAR/RXR complexes22,23 are able to interact with Sp1. Therefore, the interaction of PML-RARα with Sp1 could be mediated by the RARα part as well as the PML part of the fusion protein. Here we show that PML-RARα binds Sp1 and that this binding is significantly less efficient when the coiled-coil domain is deleted. The lack of response of the ID1 and the ID2 promoters to RARα/RXR, PLZF-RARα, and PML-RAR/ΔCC (Figures 2, 5) suggests that the PML part of the fusion protein is essential for regulating transcription.

We show that PML-RARα physically interacts with Sp1 in the absence of DNA (Figure 6). Roder et al have shown that NF-Y and Sp1 interact physically in the absence of DNA,45 and we obtained the same result (Figure 6). This suggests that the PML-RARα/Sp1/NF-Y complex may form before binding to DNA. Figure 3C suggests that the PML-RARα/Sp1/NF-Y complex still binds, although less efficiently, to the ID1 promoter when one transcription factor–binding site is mutated. Figure 4C shows that the presence of a dominant-negative form of NF-Y abolishes transactivation of the ID1 promoter by PML-RARα. We hypothesize that this dominant-negative form of NF-Y disrupts the PML-RARα/Sp1/NF-Y complex and thereby impairs binding to and transactivation of the ID1 promoter. We propose a model in which PML-RARα binds to a DNA-bound Sp1-NF-Y complex, rendering the expression of these genes sensitive to ATRA, and defining a novel gain-of-function for the fusion protein (Figure 7B). In the ChIP experiments, we show that unrearranged PML is recruited to the ID1 gene (Figure 6C). The physiological meaning of this remains unclear as no effect of PML was observed in the transactivation assays.

As Sp1 is involved in the transcriptional control of various myeloid-specific genes,47,48 deregulation of its target genes may be relevant in APL. For ID1 and ID2, a role in myelopoiesis and in APL was described previously. Overexpression of ID1 or ID2 in NB4 cells inhibits their proliferation and induces a G0/G1 arrest.31 In addition, ectopic expression of ID1 in CD34+ cells inhibited eosinophil development, whereas neutrophilic differentiation was enhanced. Expression of ID2 accelerated the definitive maturation of myeloid cells.49 Other genes may be targeted by a similar mechanism as well. The promoter of the important retinoic acid–responsive gene C/EBPβ was transactivated by PML-RARα, but also lacks a consensus RARE within the tested region.50,51 Possibly, also this gene is (de)regulated by tethering of PML-RARα to the promoter through protein-protein interactions rather than by direct DNA binding.

Apart from the DNA-binding domain from RARα, the coiled-coil domain of PML was shown to be important for optimal induction of terminal differentiation by the fusion protein.52 This suggested that homodimerization of PML-RARα is an important feature of the fusion protein, but might also indicate that other protein-protein interactions mediated through the PML part are involved. Several alternative RARα fusion proteins occur at low frequency (2% of the cases) in APL patients, in which the same part of RARα is fused to other proteins than PML (reviewed in Zelent et al44 ). Common to the various RARα partner proteins is the presence of a dimerization domain, suggesting that homodimerization is an important property of these fusion proteins. However, depending on the fusion partner, the sensitivity to retinoic acid differs, suggesting a broader role for the RARα partner protein than just the provision of a dimerization domain. Specifically, PLZF-RARα–positive leukemia appears to be more resistant to ATRA, which has been explained by the recruitment of corepressors by the PLZF part of the fusion protein that are not released upon treatment with ATRA.15,53 This insensitivity could be reversed, as treatment with a combination of ATRA and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) induced granulocytic differentiation in a synergistic manner.54 In addition, in transgenic mice, different types of disease with different sensitivities to ATRA developed for the various fusion proteins.7,30 Furthermore, when RARα fusion proteins were made by the coupling of RARα to artificial dimerization domains, several characteristics of PML-RARα were recapitulated in vitro, but in vivo these proteins induced leukemia with very low efficiency.55 Interestingly, when these fusion proteins were expressed in a PML−/− background, the animals still did not develop leukemia efficiently, leading to the conclusion that the mere combination of disruption of PML and dimerization of RARα does not recapitulate the full oncogenic potential of PML-RARα, and that the fusion protein has gain-of-function characteristics. Together, this showed that dimerization of RARα is important but not sufficient to reproduce the complete phenotype of PML-RARα.

It remains to be investigated whether PML-RARα recruits corepressors to the promoters of Sp1 and NF-Y target genes. This would lead to repression of gene expression in the absence of ATRA, possibly contributing to transformation of the cells, similar to the effect of PML-RARα on regular retinoic acid receptor target genes. So far, we did not observe important down-regulation of ID1 and ID2 mRNA in freshly isolated leukemia cells from APL patient cells compared with non-APL acute myeloid leukemia cells, suggesting that this is not the case (data not shown). However, as ID1 and ID2 expression in most leukemic samples was low, further studies are required.

Potentially, RXR may also be present in the PML-RARα/Sp1/NF-Y complex. RXR is an essential part of the PML-RARα complex during transformation, and synergy has been shown between ATRA- and RXR-specific agonist on transcriptional activation.24-26,56 Therefore, RXR-specific agonist may also affect transcription of Sp1 and NF-Y target genes.

In summary, we define a novel, Sp1- and NF-Y–dependent mechanism by which the PML-RARα fusion protein interferes with gene transcription. This implicates that PML-RARα (de)regulates an additional class of genes that is normally not regulated by retinoid receptors and defines a gain-of-function for the PML-RARα fusion protein.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr P. G. Pelicci (European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy), Dr F. Grignani (Perugia University, Perugia, Italy), Dr J. Campisi (University of California, Berkeley), Dr A. Tomita (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan), Dr H. Rotheneder (University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria), and Dr R. Mantovani (University of Milan, Milan, Italy) for supplying materials. We thank W.-J. Welboren and Dr M. L. Lohrum for advice on the ChIP protocol.

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant no. 03-2897).

Authorship

Contribution: S.W. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; M.C.B.-R. designed and performed research, and analyzed data; J.N., G.N., and C.A.J.E.-V. performed research and analyzed data; B.L., T.W., and B.A.R. designed research; D.G.T. analyzed data; J.H.J. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: J. H. Jansen, Central Hematology Laboratory and Dept of Hematology, Nijmegen Centre for Molecular Life Sciences, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Geert Grooteplein zuid 8, PO Box 9101, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands; e-mail: j.jansen@chl.umcn.nl.

References

Author notes

S.W. and M.C.B.-R. contributed equally to this work.

) ATRA. Mean values and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) To show transactivation by unrearranged retinoic acid receptors, cells were transfected with the RARE3-tk-luc vector, containing 3 bona fide RAREs. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) ID1 expression is increased by PML-RARα in the presence of ATRA. The zinc-inducible PML-RARα cell line U937-PR9 was grown in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of zinc for 16 hours. Cells were treated with ATRA and harvested at the indicated time points. Proteins were size-fractionated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Immunostaining was done with anti-ID1 antibody.

) ATRA. Mean values and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (B) To show transactivation by unrearranged retinoic acid receptors, cells were transfected with the RARE3-tk-luc vector, containing 3 bona fide RAREs. Mean values of 3 independent experiments (± SD) are shown. (C) ID1 expression is increased by PML-RARα in the presence of ATRA. The zinc-inducible PML-RARα cell line U937-PR9 was grown in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of zinc for 16 hours. Cells were treated with ATRA and harvested at the indicated time points. Proteins were size-fractionated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Immunostaining was done with anti-ID1 antibody.