In this issue of Blood, Italiano and colleagues reveal that platelets possess distinct granules containing specific angiogenesis-modifying factors that are selectively secreted following particular stimuli.

Although platelets are often viewed as cells merely designed to plug up holes in the blood vessel wall, they do have the capacity to modify the vasculature in other ways. For example, a frequently overlooked function of platelets is to secrete a variety of substances that stimulate or inhibit blood and vascular cells. In turn, this process can modify the developing thrombus, contribute to cell-adhesive events, and regulate the growth of the vasculature. Platelets contain a wide variety of peptides and proteins, primarily in α granules, that can modify the growth of cells in the vessel wall. The first of these compounds to be described was platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). Platelets are the major storage cells for PDGF, and their secretion of this compound plays an important role in the proliferation of smooth muscle cells within the blood vessel wall. Consequently, platelet-secreted PDGF plays a critical role in angiogenesis. Other α granule–contained modifiers of angiogenesis include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endostatin, thrombospondin, and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF).

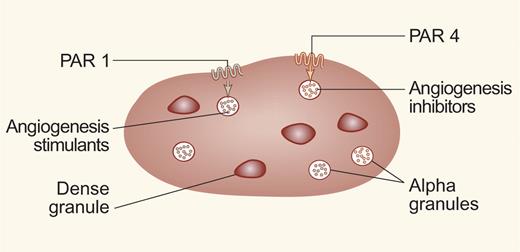

Not all alpha granules are equal. Platelets contain alpha granules and dense granules. Italiano and colleagues show that some alpha granules contain antiangiogenesis factors, and other granules contain proangiogenesis factors. Stimulation of the PAR1 receptor causes the release of angiogenesis stimulants, while stimulation of the PAR4 receptor causes release of angiogenesis inhibitors.

Not all alpha granules are equal. Platelets contain alpha granules and dense granules. Italiano and colleagues show that some alpha granules contain antiangiogenesis factors, and other granules contain proangiogenesis factors. Stimulation of the PAR1 receptor causes the release of angiogenesis stimulants, while stimulation of the PAR4 receptor causes release of angiogenesis inhibitors.

Curiously, platelets contain substances that promote angiogenesis and other substances that inhibit local angiogenesis. Releasing both types of substances would seem to be counterproductive. Italiano and colleagues postulated that under certain circumstances, platelets might exclusively secrete specific granules that promote proangiogenesis, while in response to other types of stimulation, platelets might selectively secrete granules that promote antiangiogenesis. In order for this to be true, they further hypothesized that platelets could not contain both proangiogenesis and antiangiogenesis compounds within the same granule.

In an illuminating series of experiments using double immunofluorescence or electron microscopy, the Italiano group convincingly proved both of their hypotheses. They showed that platelets contain particular granules loaded with angiogenesis stimulators and other granules loaded with angiogenesis inhibitors. Furthermore, they found that stimulation of one type of thrombin receptor (PAR4) stimulates the release of antiangiogenesis granules, whereas stimulation of the other type of thrombin receptor (PAR1) stimulates secretion of proangiogenesis granules. Their findings are surprising and raise a number of issues. How do platelets load and separate seemingly similar granules that contain physiologically competing compounds? Do platelets have discrete signaling pathways that release specific granules, or is it the strength and/or speed of the signal that causes the secretion of one exclusive class of granules? Are there markers on the surfaces of the granules that identify different classes of granules? Can therapeutics be designed to impair or enhance the release of an individual class of platelet granules? This article allows us a peek into the contents of the platelets' baggage, yet reminds us how much deeper we need to look.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■