Combined deficiency of factors V and VIII (F5F8D) is a bleeding disorder caused by mutations in LMAN1 or MCFD2. LMAN1 encodes ERGIC-53, a cargo receptor with an L-type lectin domain, and MCFD2 is a EF-hand-containing protein. We prepared a biotinylated, soluble form of ERGIC-53, which we labeled with R-phycoerythrin conjugated streptavidin. By flow cytometry, sERGIC-53-SA bound to HeLaS3 cells in the presence of calcium but only after preincubation with MCFD2. Treating the cells with endo H or incubating them with high mannose-type oligosaccharides, especially M8B, abrogated sERGIC-53-SA binding. Surface plasmon resonance experiments demonstrated that MCFD2 specifically bound to sERGIC-53 and 2 MCFD2 mutants found in F5F8D patients had a Ka that was 3 or 4 orders of magnitude lower for sERGIC-53 than for wild-type MCFD2. The Ka of sERGIC-53 and MCFD2 was measured at several pH values and calcium concentrations, and we found that at a calcium concentration less than 0.2 mM, this interaction became significantly weaker. These results demonstrate that the binding of ERGIC-53 to sugar is enhanced by its interaction with MCFD2, and defects in this interaction in F5F8D patients may be the cause for reduced secretion of factors V and VIII.

Introduction

Several sorting receptors in animal cells recognize N-linked sugar chains on glycoproteins in secretory pathway.1 These receptors bind to ligands, release them in destined organelles, and are recycled for another round of transport. ERGIC-53 and VIP36 belong to a new class of type I transmembrane sorting receptors2,3 and consist of an L-type lectin domain, a stalk domain, a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic domain. ERGIC-53 forms disulfide-linked homodimers and homohexamers through 2 cysteine residues in the stalk domain.4 ERGIC-53 is associated with the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and is continuously shuttled from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the ERGIC.5 ERGIC-53 has a C-terminal KKXX di-lysine ER-targeting signal that binds to COP I proteins and is required for recycling.6 Two C-terminal phenylalanine residues in the short cytosolic domain are also necessary for the proper trafficking of ERGIC-53 from the ER.7 The gene that encodes ERGIC-53 has been identified as a gene responsible for the autosomal recessive bleeding disorder combined deficiency of coagulation factors V and VIII (F5F8D). The levels of factors V and VIII in the plasma of people afflicted with F5F8D are only 5% to 30% of those measured in healthy individuals, and 70% of F5F8D patients have mutations in the gene that encodes ERGIC-53.8 It has subsequently been shown that the other 30% of F5F8D cases are the result of mutations in the gene that encodes MCFD2.9 Immunoprecipitation experiments have shown that these proteins form a stable, calcium-dependent complex.9 Yellow fluorescent protein-based protein fragment complementation assays have also showed that ERGIC-53 interacts with MCFD2 and its cargo proteins.10 However, the significance of the ERGIC-53–MCFD2 interaction for the sorting function of ERGIC-53 is unclear

In this current study, we have prepared recombinant soluble ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 in Escherichia coli and determined the effect of MCFD2 on the ability of ERGIC-53 to bind to sugar. In addition, interactions between ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 were further analyzed by flow cytometry, gel filtration, and surface plasmon resonance. These analyses clearly demonstrate that ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 complexes have a high affinity for sugar, especially to high mannose-type M8B. From these studies, we also determined that the interaction of these proteins is highly sensitive to the calcium concentration. These findings provide a potential mechanism by which cargo proteins can associate and dissociate from ERGIC-53 during intracellular transport.

Methods

Materials

The biotin-labeled lectins Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) and Datura stramonium agglutinin (DSA) were purchased from EY Laboratories (San Mateo, CA), and monosaccharides were purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). The synthesized high mannose-type glycans used in this study have been described previously.11,12

Construction of the plasmids for soluble ERGIC-53, MCFD2, and their mutants

A DNA fragment containing a sequence that encodes a biotinylation signal was polymerase chain reaction-amplified from the synthetic template: 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGAATTCCCGGGGGCGGTCTGAACGACATCTTCGAAGCTCAGAAAATCGAATGGCACGAATAAGGATCCGCGTTCGAAGCTCAGAAAATCGAATGGCACGAATAAGGATCCGCG-3′ with the primers; 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGAATTCC-3′ and 5′-CGCGGATCCTTATTCGTG-3′, which have Nde I and BamH I sites, respectively (shown in italics). The amplified DNA was digested with Nde I and BamH I and then cloned into pCold I (Takara, Kyoto, Japan).13 This construct, designated pCold ICbio, expressed a protein with a N-terminal 6x His-tag sequence and a C-terminal biotinylation signal.14 To express the soluble ERGIC-53 domain (sERGIC-53) corresponding to the luminal portion of ERGIC-53 (residues 31 to 278), cDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction using primers with Nde I and Sma I restriction sites and cloned it into pCold ICbio. The cDNA corresponding to residues 27–146 of MCFD2 was amplified from U937 cell cDNA with the primers 5′-GCCATATGGAGGAGCCTGCAGC-3′ and 5′-AAGGATCCCTACTGCAGTGATTTTG-3′ (Nde I and BamH I sites are shown in italics). The amplified DNA was digested with Nde I and BamH I and cloned into the pET16b vector, which contains a sequence encoding a N-terminal 6x His-tag. Point mutations were introduced into MCFD2 cDNA with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol using the following primers; 5′-TGAGAGATGAAAAGAACAATGATGGAT-3′ for MCFD2(D129E) and 5′-AACAATGATGGATACACTGACTATGCTGA-3′ for MCFD2(I136T).

Preparation of recombinant phycoerythrin-sERGIC-53-SA and MCFD2

sERGIC-53 was expressed in the BL21(DE3)pLysS strain of E coli, and the protein was purified from inclusion bodies harvested from E coli cell lysates. The proteins were solubilized, refolded by dilution as described,15 and purified first by sequential anion exchange chromatography on a UNO Q-6 column (12 mm × 53 mm; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and then by gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (10 mm × 300 mm) (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Recombinant MCFD2 and its mutants D129E and I136T were also expressed in E coli BL21(DE3)pLysS and purified by sequential Ni-affinity using a HiTrap Chelating HP (GE Healthcare), followed by anion exchange and gel filtration chromatographies as described above. Proteins were biotinylated by the biotin ligase BirA (Avidity, Denver, CO)15 and validated by a gel shift assay in polyacrylamide gels using streptavidin (SA) as described.16 To prepare R-phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled sERGIC-53-SA complexes (sERGIC-53-SA), biotinylated sERGIC-53 proteins were mixed with PE-conjugated streptavidin (PE-SA) (BD Biosystems, San Jose, CA) at a molar ratio of 4:1 at 4°C for 1 hour.

Cell-surface glycan modification

HeLaS3 cells were obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biochemical Research (Tohoku University, Miyagi, Japan) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 μg/mL penicillin, 100 U/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol less than 5% CO2 at 37°C. To modify the cell-surface glycans, cells were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of 1 mM deoxymannojirimycin (DMJ) (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 μg/mL kifunensine (KIF) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or 10 μg/mL swainsonine (SW; Calbiochem). Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H (endo H, 5.0 × 103 U; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) was added to 2 × 106 DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells suspended in 500 μL of HBSB (20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.1% NaN3). After incubation at 37°C for 3 hours, the cells were washed twice with HBSB.

Flow cytometry

HeLaS3 cells were washed with 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, and were suspended in HBSB at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/mL. Various concentrations of PE-labeled sERGIC-SA were added to 10 μL of the cell suspension at 25°C for 30 minutes in a 96-well plate (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After washing with HBSB, the cells were suspended in 200 μL HBSB containing 1 μg/mL propidium iodide. For GNA or DSA binding experiments, 10 μg/mL of each biotinylated lectin was mixed with PE-SA at a molar ratio of 4:1 and then incubated with the cells at 25°C for 30 minutes. The fluorescence of stained cells was measured using a FACS Caliber and CellQuest software (BD Biosystems). The fluorescence at 575 nm corresponding to bound PE on the cell surface was recorded and converted into a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). In total, 104 live cells gated by forward and side scattering and exclusion of propidium iodide were acquired for analysis.

To examine the effect of MCFD2 on the binding of PE-labeled sERGIC-SA to cells, various concentrations of MCFD2 or its mutants were added to the cell suspension together with PE-labeled sERGIC-SA. To test the effect of exogenous monosaccharides on the binding of ERGIC-53 to cells, 20 μg/mL PE-labeled sERGIC-SA was preincubated with various concentrations of monosaccharides at 25°C for 30 minutes before being added to cells. We also measured the effect of high mannose-type glycans on the ability of ERGIC-53 to bind to the cell surface by mixing 10 μg/mL PE-labeled sERGIC-SA with 15 mg/mL of high mannose-type glycans at 25°C for 1 hour before the addition of the cells.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis of the sERGIC-SA–MCFD2 interaction

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments were performed with the BIAcore 3000 system (Biacore International AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Recombinant MCFD2 or its mutants were coupled to CM5 sensor chips (Biacore) using an amine coupling kit according to the manufacturer's protocol until the resonance units reached approximately 350. In the coupling reactions, 1 resonance unit corresponded to an immobilized protein concentration of approximately 1 pg/mm2. Free amino groups were blocked with ethanolamine chloride. The binding of sERGIC-53 to MCFD2 or its mutants was measured in a buffer containing 10 mM MES-NaOH at pH 7.0, 6.5, and 6.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% Tween 20, and 1.0, 0.75, 0.5, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, or 0.05 mM CaCl2 at 25°C with a flow rate of 20 μL/min. sERGIC-53 at 2560, 1280, 640, 320, 160, 80, 40, and 20 nM concentrations was dialyzed against the binding buffer and then applied to the sensor chip. The regeneration of the chip surface was carried out with 10 mM MES-NaOH, pH 7.0, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% Tween 20, and 10 mM EDTA. The association constants (Ka) of sERGIC-53 and MCFD2 were calculated from the SPR binding data and BIAevaluation software (Biacore).

Analytic ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed using a Beckman Optima XL-I equipped with an An60-Ti rotor and an absorbance optical system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Double sector charcoal-filled Epon centerpieces were filled with 120 μL of MCFD2 with absorbances at 280 nm of 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125, in a buffer containing 20 mM MES-NaOH, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% Tween 20, and 1 mM CaCl2 and then centrifuged at 37°C at 20 000 rpm for 21 hours. In some cases, 1 mM CaCl2 was replaced with 5 mM EDTA. The absorbance distributions were recorded at 280 nm. The sedimentation equilibrium was analyzed using Optima XL-A/XL-I data analysis software version 60-4 (Beckman Coulter).

Results

Preparation of sERGIC-53-SA and MCFD2

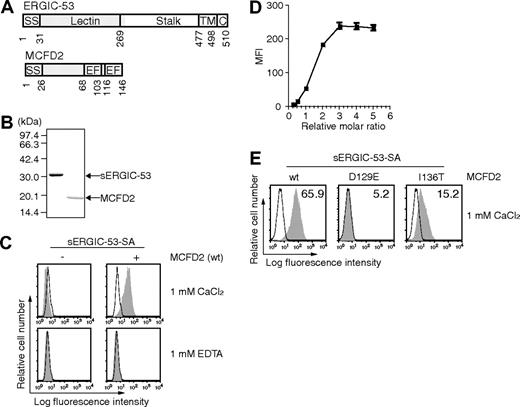

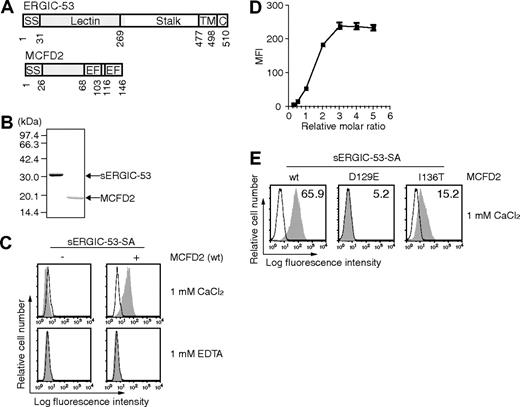

The luminal portion of ERGIC-53 (sERGIC-53) corresponding to the L-type lectin domain and a part of the stalk domain (Figure 1A) was expressed in E coli and purified (Figure 1B). sERGIC-53 was biotinylated with the biotin ligase BirA to allow for binding to SA. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis without boiling validated that sERGIC-53 was biotinylated because the band corresponding to the sERGIC-53 monomer was shifted to a higher molecular weight after the addition of SA (data not shown). To prepare sERGIC-53-SA complexes, we used the complex of sERGIC-53 and SA mixed at a ratio of 4:1 (sERGIC-53-SA). Recombinant MCFD2 and its mutants D129E and I136T were also expressed and purified from E coli and they ran as a single band of appropriate size by SDS-PAGE (Figure 1B).

sERGIC-53 binds to HeLaS3 cells in a MCFD2 and CaCl2-dependent manner. (A) The domain structures of ERGIC-53 (top) and MCFD2 (bottom). SS indicates signal sequence; Lectin, lectin domain; stalk, stalk domain; TM, transmembrane domain; C, cytoplasmic domain; EF, EF-hand domain. (B) Purified recombinant sERGIC-53 and MCFD2 (shown in gray in panel A) were electrophoresed in a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. (C) HeLaS3 cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA (left column) or sERGIC-53-SA and MCFD2 complexes at a molar ratio of 1:4 (sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2, right column), in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 or 1 mM EDTA, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (D) 20 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA was mixed with MCFD2 at ratios of 1:0.25, 0.5, 0.75,1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, and then added to the cells. The binding was monitored by flow cytometry. (E) 10 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA was preincubated with wild-type (wt) MCFD2 or the D129E and I136T mutants at a ratio of 1:4 before being added to HeLaS3 cells and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. Filled histograms indicate the cells bound to sERGIC-53-SA or sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2. Thin lines show the background staining of PE-SA. The numbers in each panel indicate the MFI. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

sERGIC-53 binds to HeLaS3 cells in a MCFD2 and CaCl2-dependent manner. (A) The domain structures of ERGIC-53 (top) and MCFD2 (bottom). SS indicates signal sequence; Lectin, lectin domain; stalk, stalk domain; TM, transmembrane domain; C, cytoplasmic domain; EF, EF-hand domain. (B) Purified recombinant sERGIC-53 and MCFD2 (shown in gray in panel A) were electrophoresed in a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. (C) HeLaS3 cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA (left column) or sERGIC-53-SA and MCFD2 complexes at a molar ratio of 1:4 (sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2, right column), in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 or 1 mM EDTA, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (D) 20 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA was mixed with MCFD2 at ratios of 1:0.25, 0.5, 0.75,1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, and then added to the cells. The binding was monitored by flow cytometry. (E) 10 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA was preincubated with wild-type (wt) MCFD2 or the D129E and I136T mutants at a ratio of 1:4 before being added to HeLaS3 cells and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. Filled histograms indicate the cells bound to sERGIC-53-SA or sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2. Thin lines show the background staining of PE-SA. The numbers in each panel indicate the MFI. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA binds to HeLaS3 cells in the presence of MCFD2

Previously, we detected weak sugar interactions with VIP36-SA by flow cytometry.16 We followed this same approach using sERGIC-53 as a substrate. sERGIC-53 was complexed with PE-labeled SA (PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA) and incubated with HeLaS3 cells to determine whether sERGIC-53 could bind to the surface of HeLaS3 cells. L-type lectin domain of ERGIC-53 has 35.5% and 34.1% amino acid sequence identity with those of calcium-dependent cargo receptors VIP36 and VIPL, respectively. Therefore, we examined the ability of PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA to bind to HeLaS3 cells in the presence of calcium. We found that PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA alone did not bind to HeLaS3 cells in either the presence or absence of calcium (Figure 1C left panels). In contrast, PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA preincubated with recombinant MCFD2 bound to these cells in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 (Figure 1C upper right). The amount of bound sERGIC-53-SA was positively correlated with the amount of MCFD2 (Figure 1D), indicating that MCFD2 is sufficient for the binding of sERGIC-53-SA to cells. Interestingly, when these experiments were repeated with MCFD2(D129E) or MCFD2(I136T), the binding of PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA to HeLaS3 cells was much lower than wild-type MCFD2 (Figure 1E). Because these mutations were identified in F5F8D families,9 these data suggest that a decrease in the ability of ERGIC-53 to bind to cell surface may result in secretion defects of factors V and VIII.

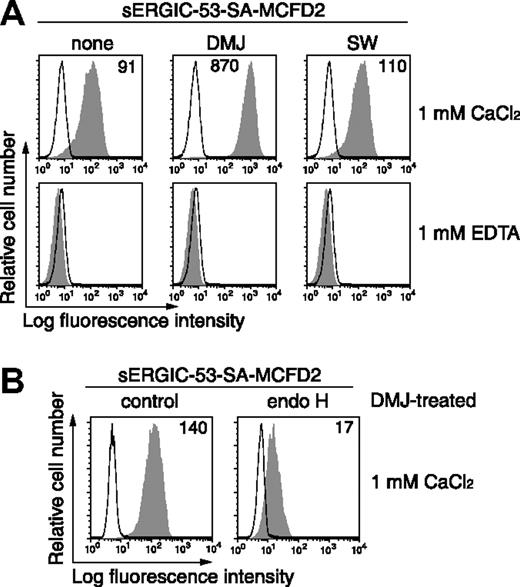

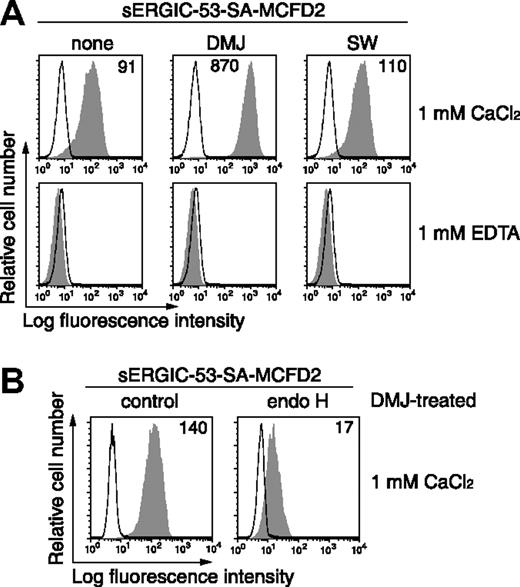

We next determined whether the binding of sERGIC-53-SA to HeLaS3 cells depends on the presence of sugar chains on the cell surface by examining sERGIC-53-SA binding following treatment with the α-mannosidase inhibitors DMJ, KIF, or SW. DMJ inhibits ER α-mannosidase I and II and causes accumulation of the Man9GlcNAc2 (M9).17,18 KIF strongly inhibits ER α-mannosidase I but not ER α-mannosidase II and causes the accumulation of M9 and a M8C isoform.19 SW, which inhibits Golgi α-mannosidase II, causes hybrid-type glycans to be expressed on the cell surface.20 By reverse- and normal-phase HPLC and MALDI-TOF-MS analysis, of all the sugars expressed in HeLaS3 cells, 36.2% are complex-type N-glycans, 42.4% of high mannose-type N-glycans, and the remaining other types of sugar chains are present on the cell surface. After treatment of HeLaS3 cells with 1 mM DMJ for 24 hours, complex-type glycans decreased from 36.2% to 2.7%, whereas the percentage of high mannose-type glycans, in particular Man7–9GlcNAc2, increased from 30.7% to 69.6%.16 These results were confirmed by both increased binding of GNA, a high mannose-type selective lectin, and decreased binding of DSA, a complex-type selective lectin, following DMJ treatment (data not shown). sERGIC-53-SA preincubated with MCFD2 (sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2) had a 10-fold higher affinity to DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells than to untreated cells (Figure 2A). These complexes also bound preferentially to KIF-treated HeLaS3 cells in the same manner (data not shown); however, the levels of complex binding were unaffected by SW treatment (Figure 2A). HeLaS3 cells were then cultured for 3 hours in DMJ in the presence or absence of endo H before adding the sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 complexes. Although the binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 to DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells decreased after 3 hours of incubation, it was reduced 8-fold when the cells were treated with endo H (Figure 2B), indicating that PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 selectively binds to high mannose-type glycans on the cell surface. sERGIC-53-SA alone is capable of binding weakly to HeLaS3 cells but only after DMJ treatment (data not shown). Therefore, ERGIC-53 alone can bind to glycans rich in mannose, which suggests that a function of MCFD2 is to enhance the ability of ERGIC-53 to bind to sugars.

The binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 to DMJ- or SW-treated HeLaS3 cells. (A) HeLaS3 cells were cultured in the presence of 1 mM DMJ or 10 μg/mL SW for 24 hours. The binding of 20 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (filled histograms) or PE-SA (thin lines) to the cells was measured by flow cytometry. The numbers in each panel indicate the MFI. (B) HeLaS3 cells cultured in the presence of 1 mM DMJ were incubated with or without 104 U/mL of endo H at 37°C for 3 hours. The cells were then mixed with 20 μg/mL PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (filled histograms) or PE-SA (thin lines). The data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

The binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 to DMJ- or SW-treated HeLaS3 cells. (A) HeLaS3 cells were cultured in the presence of 1 mM DMJ or 10 μg/mL SW for 24 hours. The binding of 20 μg/mL sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (filled histograms) or PE-SA (thin lines) to the cells was measured by flow cytometry. The numbers in each panel indicate the MFI. (B) HeLaS3 cells cultured in the presence of 1 mM DMJ were incubated with or without 104 U/mL of endo H at 37°C for 3 hours. The cells were then mixed with 20 μg/mL PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (filled histograms) or PE-SA (thin lines). The data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

Sugar-binding specificity of sERGIC-53

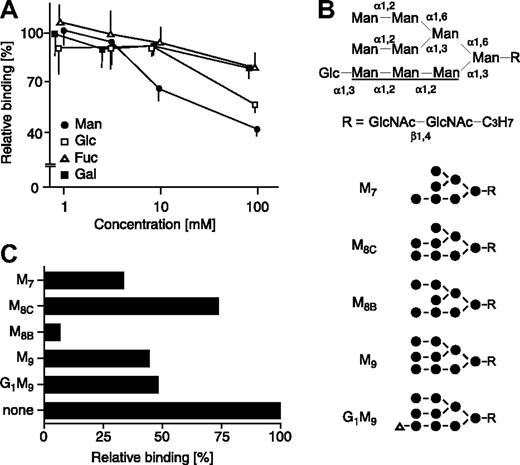

We next tested the effect of various monosaccharides on the binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 to DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells. The binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 was strongly inhibited by exogenous mannose in a dose-dependent manner and was weakly inhibited by glucose and N-acetylglucosamine, whereas galactose, N-acetylgalactosamine, and fucose had no effect (Figure 3A). We then carried out an inhibition assay with a panel of high mannose-type glycans (Figure 3B). As shown in Figure 3C, M8B was the most potent inhibitor tested. M9 (a precursor of M8B), M7 (a product of M8B), and G1M9 moderately inhibited sERGIC-53 binding. M8C, which is an isomer of M8B, was the weakest inhibitor among the oligosaccharides tested. These data indicate that ERGIC-53 preferentially binds to M8B, which makes it distinct from VIP36 and VIPL, which recognize the A arm (Figure 3B) of deglucosylated high mannose-type glycans16,21 and calnexin and calreticulin, which bind specifically to the glucosylated A arm.22

The binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 to DMJ-treated cells is inhibited by mannose and high mannose-type glycans. (A) sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (20 μg/mL) and the indicated concentrations of various monosaccharides were mixed with DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells. The binding of sERGIC-53-SA in the presence of each monosaccharide is shown relative to the absence of monosaccharide, adjusted to 100%. The data shown are means of 3 independent experiments. Man indicates mannose; Glc, glucose; Fuc, fucose; Gal, galactose. The inhibition by N-acetylgalactosamine and N-acetylglucosamine is similar to the inhibition by galactose and glucose, respectively (data not shown). (B) Structures of high mannose-type glycans used in inhibition assay are shown. The A arm of the glycan is underlined. Man, mannose (●); Glc, glucose (▵); GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine. (C) sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (10 μg/mL) and various high mannose-type glycans (15 mg/mL) were added to DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells. The binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 in the presence of each oligosaccharide is shown relative to that in the absence of oligosaccharide (none) adjusted to 100%.

The binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 to DMJ-treated cells is inhibited by mannose and high mannose-type glycans. (A) sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (20 μg/mL) and the indicated concentrations of various monosaccharides were mixed with DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells. The binding of sERGIC-53-SA in the presence of each monosaccharide is shown relative to the absence of monosaccharide, adjusted to 100%. The data shown are means of 3 independent experiments. Man indicates mannose; Glc, glucose; Fuc, fucose; Gal, galactose. The inhibition by N-acetylgalactosamine and N-acetylglucosamine is similar to the inhibition by galactose and glucose, respectively (data not shown). (B) Structures of high mannose-type glycans used in inhibition assay are shown. The A arm of the glycan is underlined. Man, mannose (●); Glc, glucose (▵); GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine. (C) sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 (10 μg/mL) and various high mannose-type glycans (15 mg/mL) were added to DMJ-treated HeLaS3 cells. The binding of sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 in the presence of each oligosaccharide is shown relative to that in the absence of oligosaccharide (none) adjusted to 100%.

Oligomeric state of MCFD2

Recombinant MCFD2 protein has a calculated molecular weight of 16 kDa based on its amino acid sequence. However, during purification, MCFD2 eluted from the Superdex 75 10/300 GL gel filtration column at an approximate molecular weight of 40 kDa (data not shown), suggesting that it may exist as a dimer under physiologic conditions. We then hypothesized that MCFD2 dimers may cross-link ERGIC-53 dimers or hexamers to form multimers and increase the avidity of ERGIC-53 for high mannose-type sugar chains.

We first measured purified MCFD2 at either at pH 6.0 or 7.0 in the presence or absence of 1 mM CaCl2 by gel filtration. For all conditions, MCFD2 eluted in a fraction corresponding to a protein of a molecular weight 40 kDa (data not shown). Moreover, recombinant MCFD2(D129E) and MCFD2(I136T) also eluted at approximately the same molecular weight (data not shown), indicating that these mutants also have the ability to dimerize. However, in contrast to the gel filtration data, sedimentation equilibrium experiments using analytical ultracentrifugation enable calculations of the native molecular mass of a sample independent of its molecular shape. The calculated mass of MCFD2 at pH 7.0 in the presence or absence of calcium by this technique was 15.5 kDa and 16.0 kDa, respectively (data not shown). The molecular weight of MCFD2(D129E) and MCFD2(I136T) was identical to wild-type MCFD2 (data not shown). These results show that MCFD2 is present as a monomer under physiologic conditions. The discrepancy between the 2 techniques may be caused by the nonglobular molecular shape of MCFD2. This observation prompted us to explore the possibility that the binding of MCFD2 may cause structural changes in ERGIC-53, which results in its enhanced ability to bind sugars.

Interactions between ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 under several pH conditions and calcium concentrations

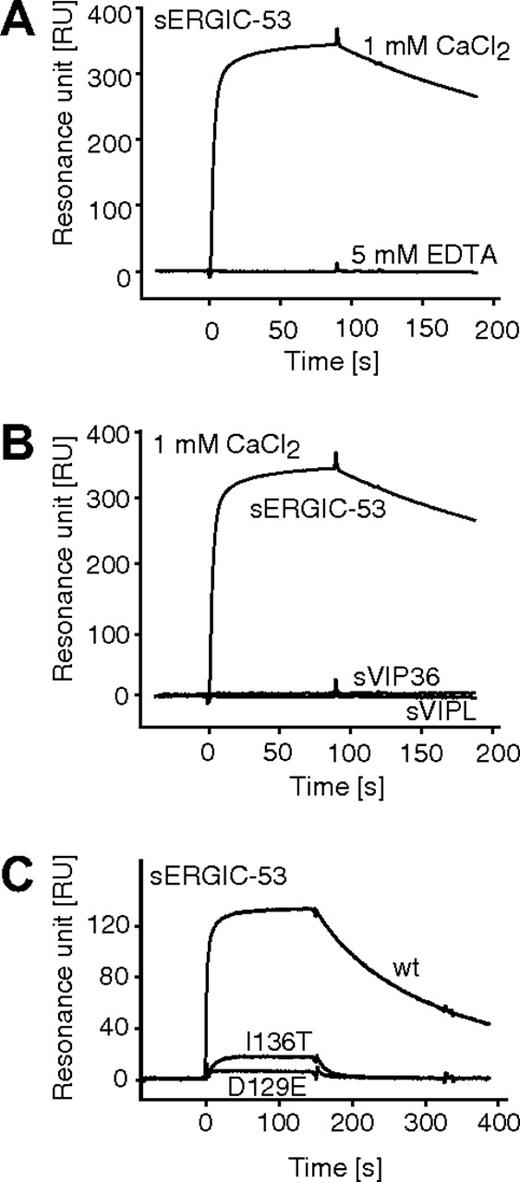

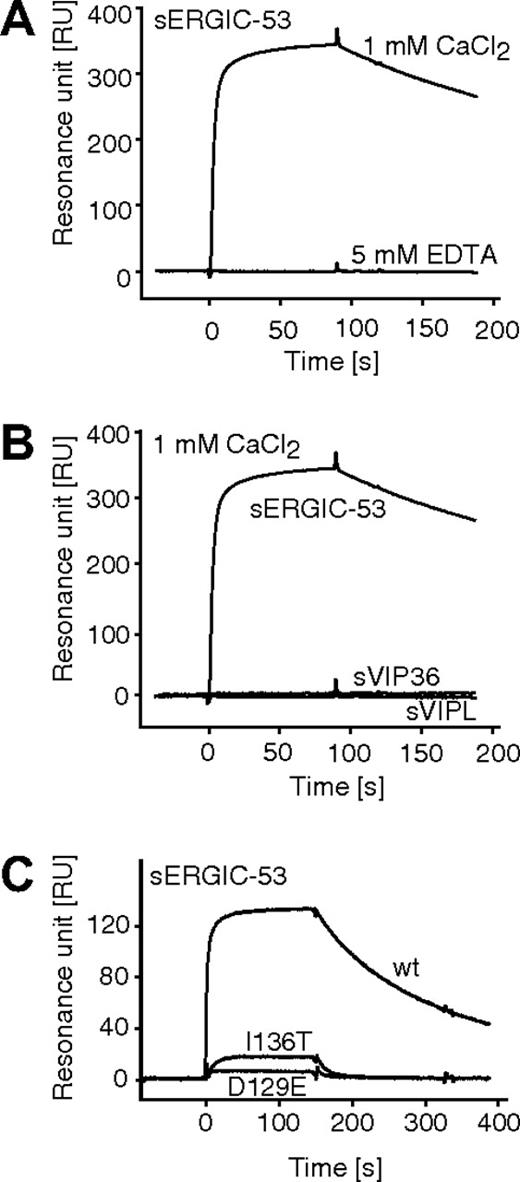

The interaction of purified sERGIC-53 with immobilized MCFD2 was quantitatively measured by surface plasmon resonance. First, we confirmed our earlier findings that sERGIC-53 specifically binds to immobilized MCFD2 in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2, and that this interaction is disrupted in the absence of calcium (Figure 4A). Neither soluble VIP36 nor VIPL bound to MCFD2 in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 (Figure 4B). Both recombinant MCFD2 and sERGIC-53 are nonglycosylated proteins expressed in E coli, indicating that the interaction between sERGIC-53 and MCFD2 is sugar-independent. We then tested the effect of various Ca2+ concentrations and pH conditions on complex formation and dissociation. The calculated Ka values obtained under several pHs and calcium concentrations are listed in Table 1. The Ka values obtained at pH 7.0, 6.5, and 6.0 were almost the same. In contrast, the calcium concentration critically affected this interaction, especially between 0.1 mM and 0.2 mM CaCl2, where a 10-fold increase was observed. The interaction of sERGIC-53 to MCFD2(D129E) and MCFD2(I136T) proteins were also analyzed by surface plasmon resonance (Figure 4C). Interactions between sERGIC-53 and MCFD2(D129E) or MCFD2(I136T) are 3 or 4 orders of magnitude weaker than wild-type MCFD2 protein at pH 7.0 in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 (Table 2). The interaction between sERGIC-53 and MCFD2(I136T) is approximately 10 times stronger than that with MCFD2(D129E) and is consistent with our earlier results showing that MCFD2(I136T) can only weakly enhance ERGIC-53 sugar-binding (Figure 1E). These results suggest that these MCFD2 mutants do not sufficiently bind to ERGIC-53 nor enhance its affinity for sugar chains. Moreover, the calcium concentration can influence the ability of ERGIC-53 to bind to sugar by affecting its interaction with MCFD2.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis of the interaction between sERGIC-53 and MCFD2. (A) sERGIC-53 (10 μg/mL) was injected (at t = 0) over the sensor chip on which MCFD2 was immobilized by amine coupling. The injection of sERGIC-53 was stopped at 90 seconds. (B) sERGIC-53, sVIP36, and sVIPL (all at a concentration of 10 μg/mL) were injected over the sensor chip on which MCFD2 was immobilized in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2. (C) In the presence of 1 mM CaCl2, sERGIC-53 (10 μg/mL) was injected over sensor chips on which MCFD2 or its mutants were immobilized.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis of the interaction between sERGIC-53 and MCFD2. (A) sERGIC-53 (10 μg/mL) was injected (at t = 0) over the sensor chip on which MCFD2 was immobilized by amine coupling. The injection of sERGIC-53 was stopped at 90 seconds. (B) sERGIC-53, sVIP36, and sVIPL (all at a concentration of 10 μg/mL) were injected over the sensor chip on which MCFD2 was immobilized in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2. (C) In the presence of 1 mM CaCl2, sERGIC-53 (10 μg/mL) was injected over sensor chips on which MCFD2 or its mutants were immobilized.

Discussion

Leguminous lectins are a large family of homologous proteins whose molecular characteristics have been studied extensively. ERGIC-53 was the first protein identified in animal cells with a homologous domain to leguminous lectins (L-type lectins).2 Amino acid residues involved in sugar- and metal-binding are conserved in both leguminous lectins and ERGIC-53, and X-ray crystallographic analysis has demonstrated their structural similarity.23,24 ERGIC-53 is a type I membrane glycoprotein consisting of an L-type lectin domain, a stalk domain, a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic domain. It forms homohexamers or homodimers through disulfide bonds between cysteines 473 and 482. We created a soluble form of ERGIC-53 containing the L-type lectin domain, a part of the stalk domain, and a biotinylation sequence at the C-terminus. Using sERGIC-53 complexed with PE-labeled SA as a tetrameric probe, we were able to measure its binding affinity to HeLaS3 cells. A similar approach was previously used to demonstrate that VIP36 and VIPL bound to sugars.16,25 The binding of the sERGIC-53 tetramer to cell surface high mannose-type glycans was greatly (10-fold) enhanced following DMJ treatment despite an only 2-fold increase in the expression of cell-surface glycans. Such an affinity enhancement resulting from multivalent lectin-carbohydrate interactions is known as the glycoside cluster effect. Enhancement in this fashion is substantially greater than the effect of just increasing the glycan concentration alone.26 Interestingly, PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA could only bind to cell surfaces in the presence of MCFD2 and calcium. The amount of MCFD2 required for binding was at a 3:1 to 4:1 (MCFD2/sERGIC-53-SA) stoichiometry. PE-labeled ERGIC-53-SA and PE-labeled MCFD2-SA complexes did not bind to HeLaS3 cells alone (Figure 1 and data not shown). However, ERGIC-53 bound to the cell surface in the presence of MCFD2. This indicates that MCFD2 enhances the binding of ERGIC-53 to cell surfaces and does not directly interact with the cells. In contrast, Nyfeler et al reported that knocking down of MCFD2 has no effect on the ability of ERGIC-53 to bind to the well-known cargo proteins cathepsin Z and cathepsin C.27 Moreover, Appenzeller-Herzog et al reported that cathepsin Z and cathepsin C interact with ERGIC-53 through its oligosaccharide and β-hairpin loop structure motif.28 In the case where the cargo proteins depend on both sugar–protein and protein–protein interactions with ERGIC-53, the enhancement of binding by MCFD2 may not be as significant.

We further investigated the mechanism by which MCFD2 controls ERGIC-53 binding to HeLaS3 cells. The association constants (Ka) of leguminous Griffonia simplicifolia isolectins dramatically increase as the isolectin increases its multimeric complexity.29 Therefore, we tested whether the ability of ERGIC-53 to bind to HeLaS3 cells in the presence of MCFD2 is the result of ERGIC-53 cross-linking induced by MCFD2 multimers. Because ERGIC-53 is present as a dimer and a hexamer, it may be cross-linked. We measured the relative molecular mass of MCFD2 in solution. Although the purified MCFD2 eluted from the gel filtration column at a molecular weight corresponding to a dimeric structure, sedimentation equilibrium data obtained from ultracentrifugation analysis showed that MCFD2 acts as a monomer at several pHs and in the presence or absence of calcium. The aberrant mobility of MCFD2 through the gel filtration column may be the result of its 2 EF-hand motifs at its C-terminus. Therefore, the enhanced binding affinity of ERGIC-53 to the cell surface is likely the result of a conformational change resulting from its interaction with the MCFD2 monomer. A crystal structural study of rat ERGIC-53 demonstrated that a unique surface patch consisting of residues conserved only in ERGIC-53 orthologs was present opposite to the sugar-binding site on ERGIC-53.23 Because such a patch is not present in leguminous lectins, VIP36, or VIPL, it may be required for the unique interaction between MCFD2 and ERGIC-53.

PE-labeled sERGIC-53-SA and MCFD2 complexes (sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2) bound stronger to DMJ- or KIF-treated HeLaS3 cells than to untreated cells. In addition, endo H treatment of the cells impaired binding, indicating that sERGIC-53-SA-MCFD2 preferentially binds to higher molecular weight high mannose-type sugar chains. Further inhibition experiments using several high mannose-type oligosaccharides demonstrated that ERGIC-53 preferentially binds to M8B, which is a product of M9 oligosaccharides after ER α-mannosidase I digestion.17 M9 oligosaccharides are one of the best ligands for the ER-resident protein VIPL.25 A direct interaction of ERGIC-53 and VIPL was previously proposed because of the observation that overexpression of VIPL resulted in the redistribution of both ERGIC-53 and the lectin-impaired ERGIC-53(N156A) mutant without affecting the cycling of the KDEL receptor or the overall morphology of the early secretory pathway.30 These observations suggest that newly synthesized glycoproteins may be transferred from VIPL to ERGIC-53 in the ER. ER α-mannosidase II, also known as soluble neutral/cytosol mannosidase, is generally thought to be involved in the processing of N-glycans in the ER by translocating them from the cytosol and converting M9 oligosaccharides to M8C in the absence of Co2+.17 However, it has recently been shown that this enzyme is localized to the cytosol and not the ER, and is involved in free oligosaccharide processing in the cytosol to produce M5 oligosaccharides.31,32 Appenzeller et al reported that preincubation of Lec1 cells with DMJ prevents mannose-trimming from M9 to M8B on cathepsin Z but has no effect on the cross-linking of cathepsin Z and ERGIC-53.33 Cathepsin Z has both high mannose-type glycan and β-hairpin peptide motifs that are essential for efficient ERGIC-53-mediated ER export.28 Mannose-trimming cathepsin Z may not be sufficient to disrupt ERGIC-53 binding, especially considering that M9 is capable of interacting with ERGIC-53 (Figure 3C). In the case when FVIII is the ligand, the treatment of cells with DMJ stably expressing ER-resident ERGIC-53 enhanced the interaction between FVIII and ERGIC-53 approximately 15%, compared with an untreated control.34 FVIII also interacts with ERGIC-53 through its high mannose-containing N-glycans that are densely situated within the B domain of FVIII as well as through protein–protein interactions.34 Although these well-known cargo proteins, cathepsin Z and FVIII, bind to ERGIC-53 through both sugar–protein and protein–protein interactions, many other ligands that bind to ERGIC-53 predominantly through N-glycans–mediated interactions may also be present in the cells. These unidentified ligands may not be easily detected by conventional biochemical approaches because they may have weak sugar–protein interactions and/or relatively low expression levels.

It has been proposed that the M8B oligosaccharide is a substrate for ER-associated degradation (ERAD). This hypothesis is based on the observation that ERAD is significantly delayed by treating cells with specific inhibitors of ER α-mannosidase I (KIF or DMJ),35 which block the enzyme that preferentially removes the α-mannosyl residues at the B branch of the high mannose-type oligosaccharide M9 to form M8B. However, recent studies have demonstrated that the carbohydrate determinant triggering ERAD may not be restricted to M8B as previously thought. EDEM1,36 EDEM2,37 and EDEM338 were reported to have endogenous mannosidase activity producing M5, M6, and M7 species, and the presence of such oligosaccharides on misfolded glycoproteins targets them for ERAD.39,40 Therefore, the M8B structure is not the targeting signal for ERAD.

Intracellular receptors can be regulated by subtle pH gradients or changes in the calcium concentration. Appenzeller-Herzog et al reported that the pH sensitivity of ERGIC-53 increased when calcium concentrations are low and that the dissociation of cargo proteins may occur in acidic conditions by protonation of the ligand-binding site of ERGIC-53.41 The interaction of MCFD2 to ERGIC-53 dramatically enhanced its affinity for sugar. To understand the mechanism by which cargo proteins become dissociated from ERGIC-53, we examined the interaction between ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 under several pH conditions and calcium concentrations using surface plasmon resonance. The calculated Ka values at pH 7.0, 6.5, and 6.0 were nearly identical and the pHs found in the ER, ERGIC, and Golgi compartments had no effect on the interaction between ERGIC-53 and MCFD2. In contrast, the calcium concentration dramatically affected this interaction. Ka values at 0.05 mM calcium (1.05–2.18 × 106 M−1) are approximately 100 to 400 times less than the Ka values at 1.0 mM calcium (1.67–3.56 × 108 M−1). Furthermore, the interaction between ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 was undetectable in the absence of calcium.

ERGIC-53 was initially defined as a marker predominantly localized to the ERGIC.42 The ERGIC is a complex membrane system between the rough ER and the Golgi, and it has been proposed to be a specialized domain of the ER43 or cis-Golgi.44 However, several subsequent studies have confirmed that the ERGIC is an independent structure that is not continuous with the ER or the cis-Golgi and has evolved in parallel with the increasing complexity of the secretory pathway in higher organisms.45 Interestingly, high resolution calcium mapping obtained in PC12 cells by electron energy loss imaging analysis showed that total calcium levels in the ER and Golgi were high, but the levels in the ERGIC were undetectable.46 These observations indicate that cargo proteins bound to ERGIC-53-MCFD2 through sugar–protein interactions may be released by the dissociation of MCFD2 from ERGIC-53 in the ERGIC. When the dissociated ternary complex of ERGIC-53, MCFD2, and cargo proteins are then transported from the ERGIC to the cis-Golgi, ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 are likely to form complexes again because the association between ERGIC-53 and MCFD2 is very strong (Ka ∼5 × 107 M−1 at pH 6.5) in the presence of 0.3 mM calcium, which resembles the environment in the cis-Golgi (Table 1). However, released cargo with a significantly lower Ka value (∼104 M−1) (Koichi Kato, Nagoya City University, oral communication, August 2, 2007) may not reform complexes with ERGIC-53-MCFD2 in the Golgi. Furthermore, the sugar moieties of released cargo proteins may be processed into smaller molecular weight high mannose-type and complex-type sugars, which may prevent protein interactions with ERGIC-53-MCFD2. When ERGIC-53 recycles from the cis-Golgi back to the ER through its interaction with the cytosolic dilysine signal within COP I coat vesicles,47 MCFD2, but not the cargo proteins, may also be recycled. This is consistent with the observation that ERGIC-53 retains MCFD2 intracellularly and that free MCFD2 is not secreted into the culture medium.27

Nineteen different mutations in the LMAN1 (ERGIC-53) gene have been reported to date. Each mutation behaves as a null allele that abolishes protein expression.48,–50 Seven MCFD2 mutations have been identified in 10 families.50 More recently, novel mutations in LMAN1 and MCFD2 have been identified in F5F8D patients, including evidence for regulatory mutations that abolish LMAN1 mRNA expression.51 In our surface plasmon resonance analysis, mutated MCFD2(D129E) and MCFD2(I136T) from F5F8D patients weakly interacted with ERGIC-53 in the presence of 1 mM calcium (Ka = 1.42 × 104 M−1 and 1.01 × 105 M−1, respectively). Measurement of the Ka values of mutated MCFD2 and ERGIC-53 may be informative when analyzing patients with significant reductions of factors V and VIII in their blood.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Authorship

Contribution: N.K. and Y. Ichikawa performed research and analyzed data; I.M., K.T., and Y. Ito prepared oligosaccharides; N.M. and K.Y. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kazuo Yamamoto, Department of Integrated Biosciences, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, University of Tokyo, Bioscience BLD 602, 5-1-5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba, 277-8562 Japan; e-mail: yamamoto@k.u-tokyo.ac.jp.