Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cell sense virally infected cells and tumor cells through multiple cell surface receptors. Many NK cell–activating receptors signal through immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activation motif (ITAM)–containing adapters, which trigger both cytotoxicy and secretion of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). Within the ITAM pathway, distinct signaling intermediates are variably involved in cytotoxicity and/or IFN-γ secretion. In this study, we have evaluated the role of protein kinase C-θ (PKC-θ) in NK-cell secretion of lytic mediators and IFN-γ. We found that engagement of NK-cell receptors that signal through ITAMs results in prompt activation of PKC-θ. Analyses of NK cells from PKC-θ–deficient mice indicated that PKC-θ is absolutely required for ITAM-mediated IFN-γ secretion, whereas it has no marked influence on the release of cytolytic mediators. Moreover, we found that PKC-θ deficiency preferentially impairs sustained extracellular-regulated kinase signaling as well as activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and the transcription factors AP-1 and NFAT but does not affect activation of NF-κB. These results indicate that NK cell–activating receptors require PKC-θ to generate sustained intracellular signals that reach the nucleus and promote transcriptional activation, ultimately inducing IFN-γ production.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are armed with an array of activating receptors that trigger exocytosis of cytolytic granules and production of cytokines. Many of these receptors, such as NKRP1C, CD16, Ly49D, and Ly49H, deliver intracellular activating signals by associating with the transmembrane adaptors CD3ζ, FcRγ, or DAP12 that contain a cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM).1-4 Tyrosine residues located within these conserved ITAM sequences become phosphorylated by Src family kinases after ligation with cognate ligand or after antibody-mediated cross-linking. In turn, these ITAM-based adaptors recruit the protein tyrosine kinases Syk and ZAP70 and the transmembrane adaptor proteins LAT and LAT2 (also called NTAL and LAB),5 resulting in recruitment and activation of downstream effector molecules, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K),6-8 the phospholipases PLCγ1 and PLCγ2,9-12 the guanosine triphosphate-guanosine diphosphate exchange factors Vav2 and Vav3,13 and the MAP kinase extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK).14 NK cell–activating receptors that signal through ITAM-containing adapters trigger both cytotoxicy and secretion of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). Not all NK cell–activating receptors possess this potential; the NKG2D receptor associates instead with the adaptor protein DAP10, which contains a cytoplasmic YINM motif that directly recruits PI3K and the Grb2-Vav1 complex rather than Syk or Zap70.2,15-18 This DAP10-dependent pathway alone, which is sufficient for inducing cytotoxocity, is inefficient for triggering cytokine production.19

Within the NK-cell ITAM-based pathway, signaling intermediates are differentially involved in cytotoxicity and IFN-γ secretion. PLCγ2, the predominant isoform of PLCγ in murine NK cells, is required for both cytotoxicity and IFN-γ secretion,9,11 whereas the Vav isoforms are essential only for cytotoxicity.13,20 In contrast, CD45, a protein tyrosine phosphatase that regulates Src family kinases, is required for IFN-γ secretion but not cytotoxicity.21,22 The p110γ catalytic subunit of PI3K is also primarily required for IFN-γ secretion.23 In this study, we have evaluated the involvement of protein kinase C-θ (PKC-θ) in NK-cell secretion of lytic mediators and IFN-γ. PKC-θ is a member of the novel PKCs family that is primarily expressed in T cells, muscle cells, and platelets.24 We hypothesized that PKC-θ could function as a signaling intermediate downstream of NK cell–activating receptors because of its well-documented role in the ITAM pathway of the T-cell receptor (TCR). In particular, PKC-θ in T cells is required for secretion of interleukin-2 (IL-2), proliferation, and differentiation of CD4+ T cells into IFN-γ–secreting Th1 cells.24-27 In T cells, activation and recruitment of PKC-θ to the TCR complex require diacylglycerol (DAG), which is generated by PLCγ1 through the hydrolysis of the phosphoinositides PI4,5P2.28 In addition, several signaling intermediates contribute to PKC-θ activation as well, such as Vav1, PI3K,29,30 SLP76,31 and the protein kinase PDK1.32,33 In turn, PKC-θ phosphorylates CARMA1,34 resulting in formation of a complex with Bcl-10 and MALT1 that activates the transcription factor NF-κB.28 In this regard, PKC-θ–deficient T cells have been shown to exhibit a major defect in the activation of NF-κB and AP-1.25 In contrast, T cells from another PKC-θ–deficient mouse demonstrated a preferential defect in NFAT activation.26 Thus, in T cells, PKC-θ appears to be essential for linking TCR and ITAM signaling to the activation of NF-κB, AP-1, and NFAT.35

Consistent with a potential role of PKC-θ in NK-cell receptor signaling, NK cells lacking PLCγ2, which is responsible for generating DAG from PIP2 in murine NK cells, are incapable of cytolysis and IFN-γ secretion in response to receptor engagement.9-11 Moreover, NK cells lacking PKC-θ downstream effectors, Bcl-10, CARMA1, or MALT1,36-38 exhibit a defect of IFN-γ secretion and NF-κB activation, although cytotoxicity in these cells is normal. Here we report that NK cells express PKC-θ and that engagement of NK-cell receptors that signal through ITAMs results in prompt PKC-θ activation. Analyses of NK cells from PKC-θ–deficient mice indicate that PKC-θ is required for ITAM-mediated IFN-γ secretion, whereas it has no marked influence on the release of cytolytic mediators. Moreover, we report that PKC-θ deficiency preferentially impairs sustained ERK activation as well as c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), c-Jun, AP-1, and NFAT activation, whereas NF-κB activation is substantially intact. Thus, in NK cells, the ITAM pathway relies on PKC-θ to generate strong and sustained signals that induce transcriptional activation and IFN-γ production.

Methods

Mice

PKC-θ−/− mice25 were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background until approximately 80% of the genome was C57BL/6 homozygous as determined by simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) analysis. All animal studies were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxicity against RMA-S, YAC-1, Baf/3, and EL-4 target cells was performed by standard chromium release assay using NK cells purified with DX5 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). NK cells were used either directly ex vivo or cultured in recombinant (r) IL-2 (1000 U/mL) for 8 to 10 days, as previously described.39

IFN-γ measurements

To measure intracellular content of IFN-γ, 107 total fresh splenocytes were stimulated in 12-well plates coated with 20 μg/mL purified anti-NK1.1 (PK136; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or anti-Ly49D (4E5; BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA), either in the absence or in the presence of suboptimal concentrations of IL-12 (0.1 ng/mL) (BD Biosciences PharMingen) and IL-18 (1 ng/mL) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Alternatively, splenocytes were stimulated with optimal doses of IL-12 (1 ng/mL) and IL-18 (10 ng/mL) or with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (0.5 μg/mL). After 2 hours, monensin (2 μM) was added to block cytokine export. After 4 additional hours of culture, cells were collected and Fc receptors were blocked with monoclonal antibody 2.4G2. Cells were first cell surface labeled with anti-CD3–fluorescein isothiocyanate, anti-CD19–fluorescein isothiocyanate, and either anti-DX5–R-phycoerythrin (when stimulated with anti-NK1.1) or anti-NK1.1–R-phycoerythrin (when stimulated with IL-12 and IL-18). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and counterstained with anti–IFN-γ–allophycocyanin (APC) (BD Biosciences PharMingen). To measure IFN-γ released in culture supernatants, NK cells were isolated with DX5 microbeads, cultured in IL-2 for 5 days, and then plated into 96-well plates coated with anti-NK1.1, anti-Ly49D, and anti-NKG2D (A10; BD Biosciences PharMingen) (50 μg/mL). Supernatants were collected after 15 hours and IFN-γ released was measured by cytometric bead arrays according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD CBA Mouse Inflammation Kit; BD Biosciences PharMingen). In addition, total splenocytes or DX5-purified NK cells were cultured for 7 to 10 days in IL-15 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or in IL-2, respectively; 5 × 104 cells were plated into 96-well plates and stimulated for 24 hours with different doses of IL-12 and/or IL-18. IFN-γ released in culture supernatants was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (BD Biosciences PharMingen).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

After 4-hour stimulation with PMA/ionomycin, RNA was prepared from IL-2–cultured NK cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA); 2 μg of each RNA sample was reverse transcribed to cDNA in a total volume of 20 μL, using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was amplified using gene-specific primers for IFN-γ (5′-ACAATGAACGCTACACACTGCAT and 5′-TGGCAGTAACAGCCAGAAACA) and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (5′-GCAGTACAGCCCCAAAAT and 5′-AACAAAGTCTGGCCTGTATCCAA). Reactions were set up using a iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Samples were run on duplicate using a Bio-Rad I-Cycler. Relative quantification of target mRNA expression was calculated and normalized to the expression of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase.

Immunoblot

Wild-type (WT) and PKC-θ−/− NK cells were cultured 5 to 8 days in rIL-2 (1000 U/mL). YAC-1 cells were fixed with 0.05% glutaraldehyde and then mixed with NK cells (1 × 106/sample) at an effector-to-target ratio 3:1. For NK1.1 stimulation, NK cells were preincubated with monoclonal antibody 2.4G2 to block Fc receptors, washed, and then plated on anti-NK1.1–coated wells at 37°C for different time points. In some experiments, NK cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (0.5 μg/mL) for the indicated times. Proteins from cell lysates were separated by standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for IκB-α, phosphorylated p38, ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), JNK, c-Fos, PKC (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and NFAT-1 Ser54 (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA). Antiactin, ERK, and PKC-θ antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Equal amounts of nuclear extracts (5 μg) prepared by Nuclear Extraction-Protein Extraction Reagent Kit (NE-PER; Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) were incubated with IRDye700-labeled DNA probes (LI-COR) for NFAT or AP-1.25 Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on 5% acrylamide gels and imaged with an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR).

Murine cytomegalovirus infections

Age-matched WT and PKC-θ−/− mice were infected intraperitoneal with 5 × 105 pfu of murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV). Viral titers were measured in the spleens and livers 3 days after infection as previously described.9 Intracellular IFN-γ content was measured 36 hours and 60 hours after infection by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of splenocytes, gating on NK1.1+CD3−CD19− NK cells.

Results

Conjugation with target cells and cross-linking of ITAM-containing receptors activates PKC-θ in murine NK cells

PKC-θ is primarily expressed in T cells, muscle cells, and platelets. To assess the expression of PKC-θ in murine NK cells, we purified NK1.1+CD3− NK cells from splenocytes, cultured them in IL-2, and performed immunoblot analysis with an anti–PKC-θ antibody. In parallel, we analyzed lysates of human NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and the T-cell leukemia line Jurkat. Murine NK cells expressed high levels of PKC-θ, as did human NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and Jurkat T cells (Figure 1A). We next asked whether the engagement of NK-activating receptors activates PKC-θ. To this end, NK cells were cultured with IL-2 for 7 days and stimulated with plate-bound anti-NK1.1 antibody, which cross-links NKRP1C (NKRP1CB6). Immunoblot analysis of stimulated NK cells with an antibody specific for the phosphorylated form of PKC-θ revealed overt PKC-θ activation (Figure 1B). Likewise, conjugation of NK cells with YAC-1 cells, which express the NKG2D ligands Rae1 and murine UL16-binding protein-like transcript 1 (MULT1), induced PKC-θ activation (Figure 1B). Interestingly, anti-NK1.1 cross-linking induced a more extended PKC-θ activation than target cell conjugation, probably because the plate-bound antibody engages the activating receptor more stably. From these findings, we conclude that the engagement of activating NK-cell receptors triggers PKC-θ activation.

Cross-linking NK cell–activating receptors induces PKC-θ activation. (A) Equal amounts of protein from purified murine and human NK-cell lysates were loaded and then immunoblotted with anti–PKC-θ antibody. Lysates from Jurkat and CD8+ T cells were used as positive controls. (B) PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were expanded in IL-2 and then stimulated with plate-bound anti-NK1.1 (left panel) or conjugated with fixed YAC-1 cells (right panel). Cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–phospho-PKC-θ and anti–total ERK1/2 antibodies. One experiment of 3 is represented.

Cross-linking NK cell–activating receptors induces PKC-θ activation. (A) Equal amounts of protein from purified murine and human NK-cell lysates were loaded and then immunoblotted with anti–PKC-θ antibody. Lysates from Jurkat and CD8+ T cells were used as positive controls. (B) PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were expanded in IL-2 and then stimulated with plate-bound anti-NK1.1 (left panel) or conjugated with fixed YAC-1 cells (right panel). Cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–phospho-PKC-θ and anti–total ERK1/2 antibodies. One experiment of 3 is represented.

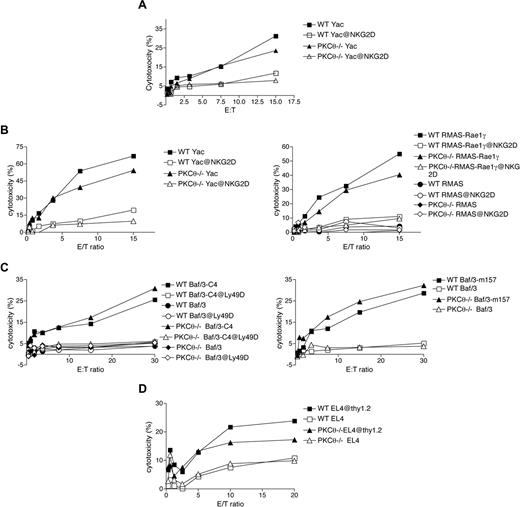

PKC-θ is dispensable for NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity

To investigate the role of PKC-θ in NK cell–mediated effector functions, we analyzed PKC-θ−/− mice25 backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background. Relative to controls, spleens from PKC-θ–deficient animals contained normal numbers of NK cells. Moreover, NK cells from these mice exhibited normal cell surface receptor repertoires, indicating that PKC-θ deficiency does not affect NK-cell development (data not shown). We next assessed the cytolytic capacity of freshly isolated (Figure 2A) and IL-2–cultured (Figure 2B-D) PKC-θ–deficient NK cells against a broad array of target cells. Target cells included YAC-1 cells and RMA-S cells transfected with Rae-1γ (RMAS–Rae-1γ), which engages NKG2D, Baf/3 cells transfected with the Chinese Hamster class I molecule Hm1-C4, which engages Ly49D, and Baf/3 cells transfected with the MCMV class I–like molecule m157, which engages Ly49H. The lytic capacity of PKC-θ−/− NK cells was comparable with WT NK cells against all target cells (Figure 2A-C). To investigate the role of PKC-θ in the NK cell–mediated killing of antibody-coated target cells (antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity) as mediated via CD16, we tested cytotoxicity against EL-4 cells coated with anti-Thy1.2 antibody. The absence of PKC-θ only slightly affected the lysis of anti-Thy1.2–coated EL-4 cells compared with WT NK cells (Figure 2D). We conclude that PKC-θ does not play a major role in NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity.

Lack of PKC-θ does not affect NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity. Ex vivo (A) and IL-2–cultured NK cells from PKC-θ−/− and WT (B-D) mice were evaluated for cytotoxicity against YAC-1 cells (A,B), RMA-S parental cells, and RMA-S cells transfected with the NKG2D ligand Rae-1γ (B), to assess NKG2D/DAP10/DAP12-independent and -dependent pathways, respectively. Cytotoxicity was measured by standard chromium release assay. IL-2–cultured WT and PKC-θ−/− NK cells were tested against parental Baf/3 cells and Baf/3 cells transfected with Hm1-C4 and m157 to assess Ly49D and Ly49H-transduced signals, respectively (C), and against anti-Thy1.2–coated EL-4 cells to assess CD16-mediated killing (antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity) (D).

Lack of PKC-θ does not affect NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity. Ex vivo (A) and IL-2–cultured NK cells from PKC-θ−/− and WT (B-D) mice were evaluated for cytotoxicity against YAC-1 cells (A,B), RMA-S parental cells, and RMA-S cells transfected with the NKG2D ligand Rae-1γ (B), to assess NKG2D/DAP10/DAP12-independent and -dependent pathways, respectively. Cytotoxicity was measured by standard chromium release assay. IL-2–cultured WT and PKC-θ−/− NK cells were tested against parental Baf/3 cells and Baf/3 cells transfected with Hm1-C4 and m157 to assess Ly49D and Ly49H-transduced signals, respectively (C), and against anti-Thy1.2–coated EL-4 cells to assess CD16-mediated killing (antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity) (D).

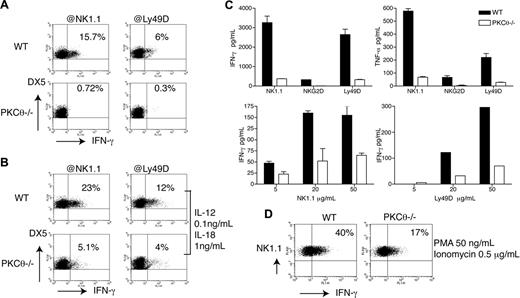

PKC-θ is required for ITAM-induced IFN-γ production

NK cells secrete IFN-γ in response to 2 types of stimuli: target cell ligands or antibodies engaging activating receptors; and cytokines, such as IL-12 and IL-18 secreted by DC and macrophages. To investigate the role of PKC-θ in IFN-γ production, we stimulated splenocytes with plate-bound anti-NK1.1 or anti-Ly49D and measured IFN-γ production by intracellular staining (Figure 3A). Moreover, because stimulation through NK1.1 (NKRP1CB6) and Ly49D alone induces limited amounts of IFN-γ, these stimulations were also performed in the presence of suboptimal concentrations of IL-12 and IL-18, which considerably amplify NK1.1- and Ly49D-induced IFN-γ production.40 In both types of stimulations, PKC-θ−/− NK cells showed marked reduction of IFN-γ secretion compared with WT NK cells (Figure 3B). Because IL-2 has been previously shown to enhance the effector functions of NK cells,41 we tested whether culture of NK cells with IL-2 could compensate for the loss of PKC-θ, reconstituting NK-cell capacity to secrete IFN-γ. NK cells from WT and PKC-θ−/− mice were cultured in IL-2, stimulated for 15 hours with plate-coated anti-NK1.1, anti-Ly49D, and anti-NKG2D, and then tested for cytokine production by cytometric bead array. Despite culture in IL-2, IFN-γ production was completely abrogated in PKC-θ−/− NK cells (Figure 3C). Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) production was equally impaired in the absence of PKC-θ (Figure 3C), consistent with a broad role of PKC-θ in ITAM-induced cytokine secretion. Thus, IL-2 activation does not compensate for loss of PKC-θ.

PKC-θ is required for ITAM-dependent IFN-γ secretion. PKC-θ−/− and WT splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with plastic-coated anti-NK1.1 and anti-Ly49D either in the absence (A) or in the presence (B) of suboptimal concentrations of IL-12 and IL-18. Intracellular IFN-γ content was measured by FACS, gating on DX5+CD3−CD19− NK cells. (C) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with plastic-coated anti-NK1.1, anti-NKG2D, and anti-Ly49D. After 16 hours of stimulation, cell culture supernatants were assayed by cytometric beads array for IFN-γ and TNF-α production. (D) PKC-θ−/− and WT splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (5 μg/mL). IFN-γ production was measured in NK1.1+CD3−CD19− NK cells by intracellular staining. Results are representative of at least 6 independent experiments.

PKC-θ is required for ITAM-dependent IFN-γ secretion. PKC-θ−/− and WT splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with plastic-coated anti-NK1.1 and anti-Ly49D either in the absence (A) or in the presence (B) of suboptimal concentrations of IL-12 and IL-18. Intracellular IFN-γ content was measured by FACS, gating on DX5+CD3−CD19− NK cells. (C) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with plastic-coated anti-NK1.1, anti-NKG2D, and anti-Ly49D. After 16 hours of stimulation, cell culture supernatants were assayed by cytometric beads array for IFN-γ and TNF-α production. (D) PKC-θ−/− and WT splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (5 μg/mL). IFN-γ production was measured in NK1.1+CD3−CD19− NK cells by intracellular staining. Results are representative of at least 6 independent experiments.

Lastly, we stimulated WT and PKC-θ−/− NK cells with ionomycin and PMA, which induce calcium mobilization and activate all PKC, respectively. IFN-γ production was severely impaired in PKC-θ−/− NK cells compared with WT NK cells also in this context, although not completely abolished (Figure 3D). Because PMA/ionomycin activates all PKC isoforms, this result demonstrates that PKC-θ is the predominant PKC isoform responsible for the ITAM pathway to IFN-γ in NK cells, although other PKC isoforms may contribute to a minimal degree.

IL-12-/IL-18–induced IFN-γ secretion is PKC-θ–independent

To address the impact of PKC-θ in IL-12- and/or IL-18–induced IFN-γ secretion, WT and PKC-θ−/− splenocytes were stimulated with different doses of IL-12, IL-18, or IL-12 and IL-18 in combination. IL-12 and IL-18 together elicited IFN-γ secretion more efficiently than IL-12 alone, whereas IL-18 alone had no effect (Figure 4A). Importantly, PKC-θ−/− NK cells did not show any difference in IFN-γ secretion compared with WT NK cells (Figure 4A). Similar results were obtained using purified NK cells cultured in IL-2 rather than total splenocytes (Figure 4B). Thus, we conclude that PKC-θ plays a pivotal role in NK- cell production of IFN-γ when elicited by activating receptors but not by IL-12 and IL-18.

Cytokine-induced IFN-γ production is PKC-θ–independent. (A) PKC-θ−/− and WT splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with the indicated doses of IL-12 and/or IL-18. Intracellular IFN-γ content was measured by FACS, gating on NK1.1+CD3−CD19− NK cells. (B) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with the indicated doses of IL-12, IL-18, or IL-12 and IL-18 for 24 hours. IFN-γ released in cell culture supernatants was determined by CBA or ELISA. IFN-γ concentrations are indicated in picograms per milliliter (IL-12, IL-18) or nanograms per milliliter (IL-12 + lL-18). (C) Splenocytes from PKC-θ−/− and WT mice were cultured for 1 week in IL-15 and then stimulated for 24 hours with the indicated doses of IL-12, IL-18, or IL-12 and IL-18. IFN-γ released in cell culture supernatants was determined by CBA or ELISA. IFN-γ concentrations are indicated in picograms per milliliter (IL-12, IL-18) or nanograms per milliliter (IL-12 + lL-18).

Cytokine-induced IFN-γ production is PKC-θ–independent. (A) PKC-θ−/− and WT splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with the indicated doses of IL-12 and/or IL-18. Intracellular IFN-γ content was measured by FACS, gating on NK1.1+CD3−CD19− NK cells. (B) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with the indicated doses of IL-12, IL-18, or IL-12 and IL-18 for 24 hours. IFN-γ released in cell culture supernatants was determined by CBA or ELISA. IFN-γ concentrations are indicated in picograms per milliliter (IL-12, IL-18) or nanograms per milliliter (IL-12 + lL-18). (C) Splenocytes from PKC-θ−/− and WT mice were cultured for 1 week in IL-15 and then stimulated for 24 hours with the indicated doses of IL-12, IL-18, or IL-12 and IL-18. IFN-γ released in cell culture supernatants was determined by CBA or ELISA. IFN-γ concentrations are indicated in picograms per milliliter (IL-12, IL-18) or nanograms per milliliter (IL-12 + lL-18).

In contrast to our results, Page et al have recently proposed that NK cells require PKC-θ to secrete IFN-γ in response to high concentrations of IL-12.42 In their study, Page et al stimulated total splenocytes that had been cultured in IL-15 for 1 week to expand NK cells. Because we stimulated freshly isolated splenocytes (Figure 4A) or purified NK cells (Figure 4B), we investigated whether the discrepancy between the 2 studies could reflect the different protocols used for stimulation of NK cells. We cultured total WT and PKC-θ splenocytes in IL-15 for 7 to 10 days, stimulated them with IL-12 and/or IL-18 and measured production of IFN-γ by ELISA and cytometric bead arrays (CBA). Stimulation of splenocytes with IL-12 or IL-18 produced little IFN-γ (Figure 4C). In contrast, splenocytes stimulated with IL-12 and IL-18 secreted abundant IFN-γ in a PKC-θ–independent fashion (Figure 4C). These results corroborate our conclusion that cytokine-induced NK-cell secretion of IFN-γ is PKC-θ–independent, whether NK cells are directly stimulated ex vivo or after in vitro expansion with IL-2 or IL-15.

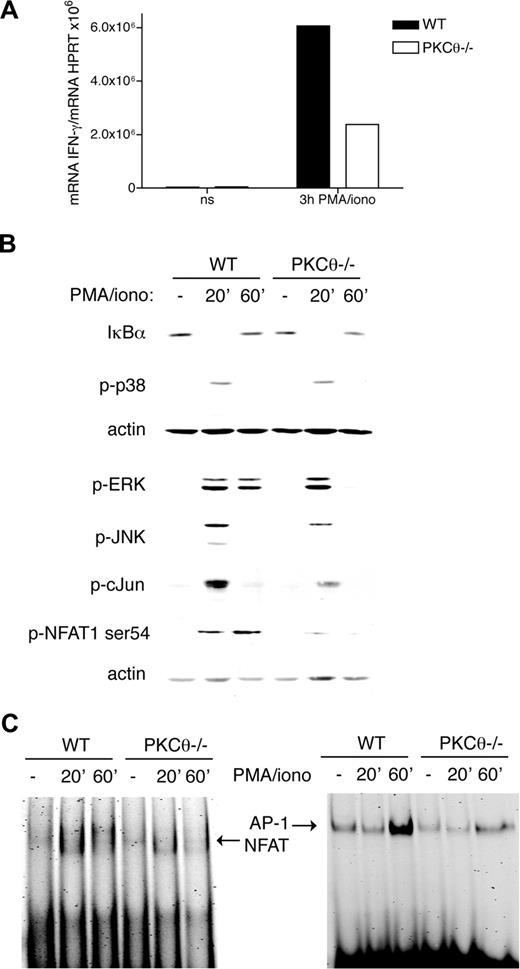

PKC-θ–mediated signals activate AP-1 and NFAT1

To address whether PKC-θ is essential for transcriptional regulation of IFN-γ, we measured IFN-γ mRNA by RT-PCR in WT and PKC-θ−/− NK cells stimulated for 3 hours with PMA/ionomycin (Figure 5A). IFN-γ mRNA induction was markedly reduced in PKC-θ−/− NK cells compared with WT NK cells. Next, we investigated which transcription factors act downstream of PKC-θ. PKC-θ has been previously shown to promote IL-2 production in thymocytes and mature T cells by activating both NF-κB and NFAT1.25,26 Canonical NF-κB activation requires phosphorylation and degradation of IκB proteins by the IκB kinase complex, which results in activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB dimers p65/p50 or c-Rel/p50.28 Stimulation of WT and PKC-θ−/− NK cells with PMA/ionomycin demonstrated that lack of PKC-θ has no effect on IκBα degradation (Figure 5B). We obtained the same result in response to NK1.1 ligation (data not shown). Thus, PKC-θ-mediated signals appear to have no impact on NF-κB activation in NK cells.

PKC-θ is required for NFAT and AP-1 activation. (A) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (0.5 μg/mL), and transcription of IFN-γ was analyzed by RT-PCR. (B) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (0.5 μg/mL). Cells were lysed and then analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-IκBα, anti–phospho-p38, ERK, JNK, c-Fos, and NFAT1-Ser54. As a loading control, membranes were probed with anti-actin antibody. (C) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated as in panel B, and then nuclear extracts were analyzed by EMSA using probes containing NFAT or AP-1 binding sites. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

PKC-θ is required for NFAT and AP-1 activation. (A) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (0.5 μg/mL), and transcription of IFN-γ was analyzed by RT-PCR. (B) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (0.5 μg/mL). Cells were lysed and then analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-IκBα, anti–phospho-p38, ERK, JNK, c-Fos, and NFAT1-Ser54. As a loading control, membranes were probed with anti-actin antibody. (C) IL-2–cultured PKC-θ−/− and WT NK cells were stimulated as in panel B, and then nuclear extracts were analyzed by EMSA using probes containing NFAT or AP-1 binding sites. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

We extended our investigation to other signaling pathways. PMA/ionomycin stimulation induced potent phosphorylation of ERK, p38, and JNK in WT NK cells. PKC-θ deficiency resulted in reduced ERK and JNK phosphorylation but had no effect on p38 phosphorylation (Figure 5B). Notably, impaired ERK phosphorylation was detected in PKC-θ–deficient NK cells only at late time points after stimulation, indicating that PKC-θ is required for sustained ERK signaling. Moreover, PKC-θ deficiency also resulted in reduced phosphorylation of c-Jun, the downstream substrate of JNK. Because Jun is a component of the transcription factor AP-1, we asked whether lack of PKC-θ affects AP-1 activation. In electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), we noted a significant decrease in AP-1 activation in PKC-θ−/− versus WT NK-cell lysates (Figure 5C). To determine whether PKC-θ is required for NFAT activation, we stimulated WT and PKC-θ−/− NK cells with PMA/ionomycin and measured phosphorylation of NFAT1 on residue Ser54, which has been shown to positively regulate NFAT activation.43 Interestingly, phospho-Ser54 was reduced in the absence of PKC-θ (Figure 5B). Moreover, analysis of nuclear extracts in EMSA demonstrated that NFAT DNA binding activity is reduced in PKC-θ−/− compared with WT NK cells stimulated with PMA/ionomycin (Figure 5C). Altogether, these results indicate that PKC-θ promotes IFN-γ transcription in NK cells, most probably through ERK, JNK, AP-1, and NFAT signaling pathways.

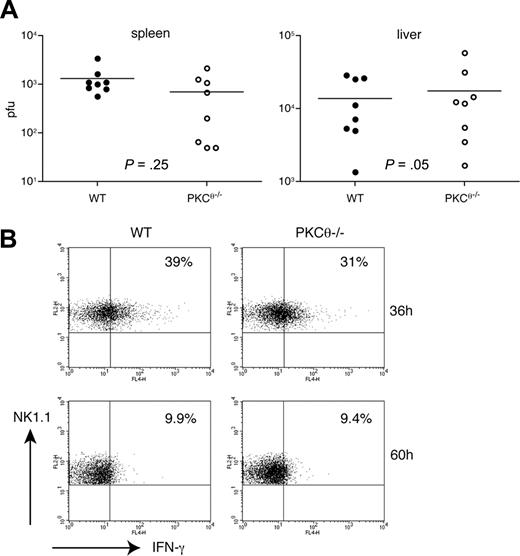

Control of early infection by murine cytomegalovirus in vivo is PKC-θ–independent

NK cells control MCMV infection by killing MCMV-infected cells and secreting IFN-γ, which activates both innate and adaptive immune responses. Whereas the first mechanism is predominant in the spleen, the second preferentially occurs in the liver.44 To investigate the impact of PKC-θ–dependent IFN-γ secretion on the ability of NK cells to control MCMV infection, we infected WT and PKC-θ−/− mice with MCMV, harvested spleens and livers 3 days after infection, and measured viral titers. WT and PKC-θ−/− mice demonstrated no significant difference in viral titers obtained from the spleens, but also in the liver (Figure 6A). Moreover, WT and PKC-θ−/− NK cells analyzed ex vivo 36 hours and 60 hours after MCMV infection exhibited similar amounts of intracellular IFN-γ (Figure 6B). These results indicate that PKC-θ–mediated IFN-γ production is not required to control acute MCMV infection.

Early control of MCMV infection is PKC-θ–independent. (A) Age-matched WT and PKC-θ−/− mice were infected intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 pfu of MCMV. Three days after infection, spleen and liver viral loads were determined by plaque assay. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Age-matched WT and PKC-θ−/− mice were infected intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 pfu of MCMV. At 36 hours and 60 hours after infection, splenocytes were analyzed ex vivo for intracellular IFN-γ content by FACS, gating on NK1.1+CD3−CD19− NK cells.

Early control of MCMV infection is PKC-θ–independent. (A) Age-matched WT and PKC-θ−/− mice were infected intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 pfu of MCMV. Three days after infection, spleen and liver viral loads were determined by plaque assay. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Age-matched WT and PKC-θ−/− mice were infected intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 pfu of MCMV. At 36 hours and 60 hours after infection, splenocytes were analyzed ex vivo for intracellular IFN-γ content by FACS, gating on NK1.1+CD3−CD19− NK cells.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified a novel function of PKC-θ in NK cells. Our results demonstrate that activating NK-cell receptors that signal through ITAM-containing adapters activate PKC-θ and that, for this class of receptors, PKC-θ is essential for induction of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Thus, there is a clear parallel between T cells and NK cells in that both TCR-induced and NK-cell receptor–induced cytokine secretion require PKC-θ. Although a recent study proposed that PKC-θ is required for IFN-γ secretion in response to high concentrations of IL-12,42 we found that IFN-γ production induced by IL-12 only or by IL-12 in combination with IL-18 is entirely PKC-θ–independent. Thus, NK cells use redundant, nonoverlapping signaling pathways for IFN-γ secretion. This result, together with the observation that PKC-θ is dispensable for NK-cell release of cytolytic granules, explains why deficiency of PKC-θ has no significant impact on the ability of NK cells to control early MCMV infection.

We observed that lack of PKC-θ impacts IFN-γ secretion but not cytotoxicity. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that NK cells lacking the protein tyrosine phosphatase CD45 are also incapable of IFN-γ secretion yet retain full cytotoxic function.21,22 The parallels between PKC-θ and CD45-deficient NK cells extend further in that both have defects in ERK and JNK signaling, whereas p38 activation remains intact. It has been proposed that CD45 is important for generating strong and sustained ITAM signals that are necessary to induce transcriptional activation of the IFN-γ gene at the nuclear level. Our results indicate that PKC-θ may be the crucial intermediate that amplifies and sustains ITAM signals, enabling prolonged ERK and JNK phosphorylation and consequently DNA-binding activity of AP-1 and NFAT. As for the signaling intermediates that link ITAMs with PKC-θ in NK cells, it is well established that all members of the novel PKC family, including PKC-θ, require DAG for activation. DAG is generated by PLCγ through enzymatic cleavage of PIP2, and PLCγ2 is the main PLCγ isoform in NK cells. Given this, PLCγ2 is the most probable candidate linking ITAMs with PKC-θ. Indeed, it has been shown that activating receptors are incapable of inducing IFN-γ in PLCγ2-deficient NK cells,9-11 as they are in PKC-θ–deficient NK cells.

Our results show that PKC-θ promotes IFN-γ production at the transcriptional level, although a supplementary posttranscriptional influence cannot be excluded. To identify which factors may mediate PKC-θ–mediated transcriptional activation of the IFN-γ gene, we investigated several candidates. In T cells, PKC-θ has been shown to phosphorylate CARMA-1, which is then recruited to form a complex with Bcl-10 and MALT-1, leading to activation of NF-κB.34 Moreover, PKC-θ has also been shown to link TCR signaling with activation of NFAT and AP-1.25,26 In concert, these nuclear factors activate transcription of cytokine genes. In NK cells, we found that PKC-θ deficiency impaired NFAT1 and AP-1, whereas NF-κB activation was preserved. Lack of PKC-θ severely compromised the binding of AP-1 to DNA, which may in turn contribute to the defect in IFN-γ transcription. In this regard, it has been shown that AP-1 binds to the proximal regulatory element of the IFN-γ promoter in T cells, thereby playing a crucial role in IFN-γ gene expression.45,46 PKC-θ may induce AP-1 activation through the JNK and its downstream transcription factor c-Jun, which is a component of AP-1. Consistent with this idea, we observed reduced activation of JNK and c-jun in PKC-θ–deficient NK cells. Moreover, activation of ERK is also reduced in PKC-θ–deficient NK cells, which may further impair AP-1 activation.47,48

PKC-θ–deficient NK cells also had defect in NFAT1 phosphorylation on residue Ser54, which mediates NFAT1 activation.43 In addition, the capacity of NFAT to bind DNA was reduced in PKC-θ–deficient NK cells. It is possible that lack of PKC-θ affects Ca2+ mobilization, as has been previously observed in T cells,26,49 thus impairing NFAT activation. The previous demonstration that NFAT binds the IFN-γ promoter in 2 sites46 and that active NFAT1 is required for IFN-γ production in CD4+ T cells50,51 is consistent with our data implying that PKC-θ–dependent NFAT activation is essential for NK-cell transcription of the IFN-γ gene. Indeed, FK506, a known inhibitor of the NFAT pathway, blocks both human and murine NK-cell production of IFN-γ.52

Recently, 3 groups independently demonstrated that Bcl-10 and CARMA1 are required for IFN-γ production and NF-κB activation in NK cells.36-38 Although PKC-θ is an upstream activator of the CARMA1/Bcl-10/MALT1 complex and, moreover, is necessary for NK-cell secretion of IFN-γ just like Bcl10 and CARMA1, PKC-θ deficiency had no impact on NF-κB activation as measured by degradation of IκBα. This result challenges the model of a linear PKC-θ–CARMA1/Bcl10/MALT1–NF-κB pathway for IFN-γ secretion, at least in NK cells, and suggests that PKC-θ and the CARMA1/Bcl-10/MALT1 complex may control IFN-γ transcription through distinct factors, NFAT, AP-1, and NF-κB, all of which contribute to IFN-γ gene transcription.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Weaver for technical advice on EMSA and Angelo Benedetti for support to A.C.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 5R01AI056139. A.C. was supported by Dottorato di Ricerca in Medicina Molecolare of the Department of Physiopathology, Experimental Medicine and Public Health, University of Siena, Italy.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: I.T. designed and performed research and wrote the paper; M.C., R.P., and A.C. performed research; S.G. and D.R.L. contributed vital reagents; and M.C. directed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marco Colonna, Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S Euclid Avenue, St Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: mcolonna@pathology.wustl.edu.