Abstract

Rab5 is a small GTPase that regulates early endocytic events and is activated by RabGEF1/Rabex-5. Rabaptin-5, a Rab5 interacting protein, was identified as a protein critical for potentiating RabGEF1/Rabex-5's activation of Rab5. Using Rabaptin-5 shRNA knockdown, we show that Rabaptin-5 is dispensable for Rab5-dependent processes in intact mast cells, including high affinity IgE receptor (FcϵRI) internalization and endosome fusion. However, Rabaptin-5 deficiency markedly diminished expression of FcϵRI and β1 integrin on the mast cell surface by diminishing receptor surface stability. This in turn reduced the ability of mast cells to bind IgE and significantly diminished both mast cell sensitivity to antigen (Ag)-induced mediator release and Ag-induced mast cell adhesion and migration. These findings show that, although dispensable for canonical Rab5 processes in mast cells, Rabaptin-5 importantly contributes to mast cell IgE-dependent immunologic function by enhancing mast cell receptor surface stability.

Introduction

Mast cells are best known for their critical roles in immunoglobulin E (IgE)–associated immediate hypersensitivity reactions and other allergic disorders.1-4 IgE primes the mast cell to undergo Ag-dependent activation by binding to the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcϵRI), a member of the immune receptor superfamily,1-4 and multivalent Ag initiates mast cell activation by cross-linking 2 or more FcϵRI-bound IgE molecules that bind to that Ag. Mast cell activation induces a variety of responses, including the release of preformed pro-inflammatory mediators (eg, histamine, β-hexosaminidase) from the cytoplasmic granules, as well as the secretion of lipid mediators, cytokines, chemokines and growth factors.1-4

Regulation of the expression of receptors and their downstream signaling pathways is critical for a cell to properly interpret and respond to the surrounding environment. Perturbations in these processes can have diverse and dramatic effects.5 Receptor regulation is particularly important for mounting optimal responses to low concentrations of ligands, such as migration in response to chemotactic factors6 or activation of secretion by Ags.3,7 Mast cells in particular are well known for being able to respond to small amounts of Ags.1-4

Although many proteins have been identified that modulate receptor traffic to and from the cell surface, members of the Rab family of small GTPases have emerged as major regulators of many of these membrane trafficking events.8-11 Like all GTPases, Rabs cycle between GDP and GTP bound conformations, with the state of nucleotide binding dictating whether the Rab protein is active (GTP bound) or inactive (GDP bound). This nucleotide cycling is catalyzed by GEFs (guanine exchange factors; catalyze GTP binding) and GAPs (GTPase activating proteins; stimulate intrinsic GTPase activity of Rabs). Several of these Rab proteins have attracted much attention, including Rab5, the major regulator of early endocytic events, Rab4 and Rab11, regulators of recycling routes, and Rab7 and Rab9, regulators of the lysosomal pathway.10 Despite intense studies of their biochemistry, the functions of these proteins in regulating the activation and signaling of intact cells have only recently been investigated. In mast cells, Rab27a and Rab27b and its effectors12,13 regulate granule motility and degranulation, whereas the role of Rab3, initially reported to be important in regulating mast cell degranulaton,14 remains to be fully clarified.15

We have shown that RabGEF1/Rabex-5 (RabGEF1), a Rab5 GEF, is critical for regulating the activation of mouse bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells (BMCMCs).16-18 We demonstrated that mast cell activation by FcϵRI cross-linking is regulated by RabGEF1's VPS9 domain, which stimulates Rab5 activity, induces receptor internalization, and dampens excessive FcϵRI-dependent mouse BMCMC activation.18 A second RabGEF1 domain, the coiled-coil (CC) domain, although dispensable for FcϵRI internalization or preventing excessive FcϵRI-dependent activation, was essential to maintain high basal levels of FcϵRI surface expression.18 This domain is also the site of interaction between RabGEF1 and Rabaptin-5, a Rab5 effector,18,19 and this interaction is required to maintain high endogenous levels of Rabaptin-5.18 The correlation that we observed between diminished FcϵRI surface expression and decreased ability to maintain Rabaptin-5 levels in RabGEF1-deficient mast cells expressing a CC-deficient RabGEF1 mutant suggested that Rabaptin-5 may be important for regulating FcϵRI trafficking and surface expression.

Although Rabaptin-5 has been proposed as an important Rab5 effector, there is uncertainty about its cellular role.20-24 In our studies of the role of RabGEF1 in the regulation of intracellular signaling, we found that mast cells activated via IgE/FcϵRI represented a tractable and informative model system for investigating such processes in intact cells.17,18 Given the importance of IgE, FcϵRI, and mast cells in the pathology of allergic disorders25 and the importance of understanding the biology of receptor trafficking, we investigated the role of Rabaptin-5 in regulating cell surface receptor expression and cellular functions in mast cells.

Methods

Information on cell culture; lentivirus production and BMCMC infection; Alexa 647, biotin, and Fab protein modifications; Western blot analysis; Transferrin (Tf) recycling assays; BSA uptake; and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). See Document S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Plasmid DNA and mast cell transfections

The following vectors were generously provided by those indicated: pEGFP-Rab5 and Rab5-Q79L (Guangpu Li, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK), pEGFP-Rab11-WT and Rab11-S25N (Victor Hsu, Harvard), pEGFP-Rab9 (Suzanne Pfeffer, Stanford University, Stanford, CA), and pEGFP-Rab4-WT and Rab4-S22N (Marci Scidmore, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY). Transfections were performed as described previously.18

Rabaptin-5 shRNA

The coding region of mouse Rabaptin-5 was analyzed with psicooligomaker (http://web.mit.edu/jacks-lab/protocols/pSico.html) and sisweb (http://sirna.sbc.su.se/), and an shRNA sequence (5′-GCTTTAGGCTATAACTACA) was identified that targeted all Rabaptin-5 isoforms. Sense and antisense oligos to this sequence (5′GCTTTAGGCTATAACTACATTCAAGAGATGTAGTTATAGCCTAAAGCTTTTTTC) were generated, annealed, and cloned into pLL3.7 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) generating pLL3.7-shR. The pLL3.7-shR construct was sequenced to assure fidelity. The empty vector pLL3.7 was used as control and demonstrates similar results as nonsense-coding shRNA constructs (E.J.R. and S.J.G., unpublished data, January 2007).

Immunofluorescence

This information is provided as supplemental data. Briefly, BMCMCs were probed with the indicated primary antibodies: α-Rab5, α-EEA1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), α-FcϵRIα (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), α-FcϵRIβ, α-FcϵRIγ, α-calnexin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), α-GCC185 (S. Pfeffer, Stanford), α-LAMP1 (Iowa Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), imaged at room temperature with the 63×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective of a TCS SP5 confocal system (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and processed with Leica LAS software version 1.5.1, build 869. Single-channel images were exported to Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), where whole image colors were balanced and images were cropped and overlaid for figures.

IL-6 ELISA

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were performed as described.16

Flow cytometry

This information is provided as supplemental data. Briefly, cells were stained with the indicated Abs: α-c-Kit, α-FcϵRIα, α-β1 integrin (all from eBioscience), α-IL4R or α-IgE (both from BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA) Abs for 30 minutes, and analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR) to generate mean fluorescent intensities (MFIs).

FcϵRI internalization

BMCMCs sensitized for 16 hours in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) + 10% fetal calf serum + 2 μg/mL of IgE (H1-DNP-ϵ 26; F.-T. Liu, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA) were resuspended in DMEM + 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) + 1 μg/mL of biotinylated anti-IgE Abs (BD Biosciences PharMingen) and incubated at 4°C for 1 hour, washed, resuspended in DMEM + 0.1% BSA, placed at 37°C for 0, 30, or 60 minutes, incubated with allophycocyanin-streptavidin (BD Biosciences PharMingen), washed, and then allophycocyanin association was quantified by FC.

FcϵRI Fab trafficking

BMCMCs adherent to fibronectin (FN)-coated cover slips by Mn2+ exposure were incubated with 0.5 μg/mL of Alexa-647 labeled Fabs at 4°C for 1 hour, washed, and moved to 37°C for the indicated times. Cells were then fixed and processed for confocal microscopy.

FcϵRI recycling

This information is provided as supplemental data. Briefly, BMCMCs were incubated with biotinylated α-FcϵRIα Fabs to saturate intracellular compartments, washed, and blocked with unlabeled monovalent SA (mSA,26 a gift from P.J. Utz, Stanford University) at 4°C. To further saturate residual surface, Fabs cells were subsequently incubated with Alexa 647-labeled-mSA at 4°C. Recycled receptors were identified as an increase in MFI assessed by FC after the cells were transferred to 37°C for the indicated times.

Receptor surface stability studies

BMCMCs were cultured in DMEM + 10% fetal calf serum supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL brefeldin A (BFA, BD Biosciences PharMingen), 1.5 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), or 50 μM Primaquine (Sigma-Aldrich). Before supplementation, surface FcϵRI or β1 integrin was assessed by FC. At the indicated time points after supplementation, aliquots of each condition were removed and processed for FC to generate MFIs. MFIs were pooled from 3 pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. For FcϵRI, data were fit to exponential decay curves with Prism statistical software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and half-lives were extrapolated from exponential decay curves.

IgE capture assay

To assess their ability to bind IgE, shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs were cultured with various concentrations of Alexa 647-conjugated-IgE in the presence or absence of BFA or CHX. Aliquots of cells were removed at the indicated times and assessed for Alexa 647-associated fluorescence by FC.

Adhesion assays

Adhesion assays were performed as described by Lam et al.27

Migration assays

Transwell BMCMC chemotaxis assays were performed as described previously.17

Statistics

Unless otherwise specified, data are expressed as mean plus or minus SEM and were examined for significance by the unpaired Student t test, 2-tailed. In some figures, means were compared with a hypothetical value of 100 using a one-sample t test.

Results

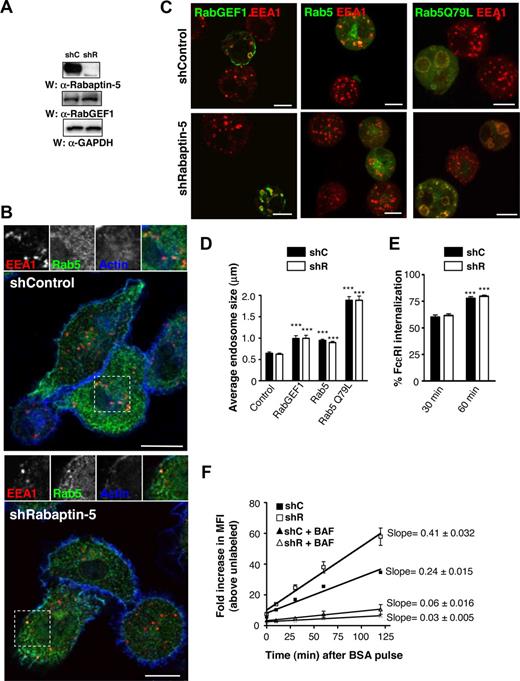

Rabaptin-5 is dispensable for canonical Rab5-mediated processes

Rabaptin-5 is a Rab5 effector, but its function in intact cells remains elusive.21-23 Rab5 regulates receptor internalization and early endosome sorting, so it is possible that Rabaptin-5 may also be important for these roles. To examine Rabaptin-5's role in BMCMCs, we diminished Rabaptin-5 levels using lentivirally delivered Rabaptin-5 specific shRNA. There are many splice variants of Rabaptin-5, so we chose a target that would silence all forms.28 Bis-cistronic lentiviral vectors stably express shRNAs and fluorescent markers, thus permitting long-term knock-down without chemical selection. Rabaptin-5 shRNA (shR)–treated BMCMCs exhibited markedly decreased (> 95%) Rabaptin-5 protein levels relative to control vector (shC)–treated cells (Figure 1A); such cells could be maintained for at least 3 months in culture during which time the shR-treated BMCMCs continued to exhibit a substantial reduction in Rabaptin-5 protein levels (data not shown). RabGEF1 levels were unchanged (Figure 1A), even though we previously reported that the RabGEF1/Rabaptin-5 interaction was necessary to stabilize Rabaptin-5 protein levels.18 The levels of other Rabaptin-5 interacting proteins, such as Rab5, Rab4, GGA1, and γ-adaptin, were also unchanged in the absence of Rabaptin-5 (Figure S1A).

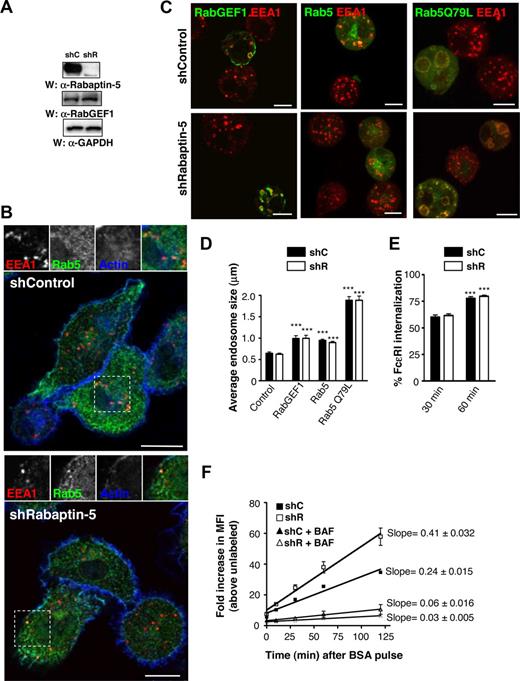

Rabaptin-5 knock-down does not impair canonical Rab5 processes in BMCMCs. (A) Total cell lysates from BMCMCs treated with control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) targeted shRNA constructs were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with the indicated primary antibodies. (B) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were processed for confocal microscopy as described in Document S1, (“Immunofluorescence”) and stained with α-EEA1 (red) and α-Rab5 (green) antibodies and phalloidin (blue) to identify the actin cytoskeleton. The regions outlined by dashed boxes are shown magnified, and as individual channels, above the overlay. (C) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were transiently transfected with the indicated GFP constructs by electroporation for 12 to 24 hours and processed for immunofluorescence as in panel B with GFP fluorescence in green and α-EEA1 in red. (D) Endosome sizes from individual shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs prepared as in panel C were measured as described in Document S1, “Immunofluorescence,” averaged, pooled from 3 separate experiments, and compared (***P < .001 vs corresponding “control” untransfected cells). (E) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were sensitized with IgE, stimulated with biotinylated α-IgE Abs for the indicated times, and surface α-IgE was assessed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the mean plus or minus SEM of percentage FcϵRI internalization determinations from 4 separate batches of BMCMCs (***P < .001 vs MFI at 30 minutes). (F) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were pulsed with 0.5 mg/mL of Cy 5-labeled BSA for 20 minutes, washed, and chased with unlabeled BSA. Associated fluorescence was measured at the indicated times after washout by flow cytometry. To prevent endosome acidification, some cells were pretreated with 50 μM of bafilomycin for 10 minutes before the BSA pulse. Graphs represent data transformed to show fold increases above unlabeled cells pooled from 3 pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. Linear regression analysis was performed to generate lines of best fit with the slopes and 95% confidence intervals noted. Scale bars in panels B and C represent 7.5 μm.

Rabaptin-5 knock-down does not impair canonical Rab5 processes in BMCMCs. (A) Total cell lysates from BMCMCs treated with control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) targeted shRNA constructs were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with the indicated primary antibodies. (B) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were processed for confocal microscopy as described in Document S1, (“Immunofluorescence”) and stained with α-EEA1 (red) and α-Rab5 (green) antibodies and phalloidin (blue) to identify the actin cytoskeleton. The regions outlined by dashed boxes are shown magnified, and as individual channels, above the overlay. (C) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were transiently transfected with the indicated GFP constructs by electroporation for 12 to 24 hours and processed for immunofluorescence as in panel B with GFP fluorescence in green and α-EEA1 in red. (D) Endosome sizes from individual shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs prepared as in panel C were measured as described in Document S1, “Immunofluorescence,” averaged, pooled from 3 separate experiments, and compared (***P < .001 vs corresponding “control” untransfected cells). (E) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were sensitized with IgE, stimulated with biotinylated α-IgE Abs for the indicated times, and surface α-IgE was assessed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the mean plus or minus SEM of percentage FcϵRI internalization determinations from 4 separate batches of BMCMCs (***P < .001 vs MFI at 30 minutes). (F) BMCMCs generated as in panel A were pulsed with 0.5 mg/mL of Cy 5-labeled BSA for 20 minutes, washed, and chased with unlabeled BSA. Associated fluorescence was measured at the indicated times after washout by flow cytometry. To prevent endosome acidification, some cells were pretreated with 50 μM of bafilomycin for 10 minutes before the BSA pulse. Graphs represent data transformed to show fold increases above unlabeled cells pooled from 3 pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. Linear regression analysis was performed to generate lines of best fit with the slopes and 95% confidence intervals noted. Scale bars in panels B and C represent 7.5 μm.

In vitro and overexpression studies suggest that Rabaptin-5 is important for Rab5 activation, probably because of Rabaptin-5's ability to potentiate RabGEF1's activity.21,23,29 To evaluate Rabaptin-5's role in steady-state endosome morphology or distribution within the cell, we examined early endosome Ag 1 (EEA1) and Rab5 localization in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs at baseline or when expressing proteins that activate Rab5 (Figure 1B,C). We noted no difference in average endosome size or distribution between shC- and shR-treated BMCMCs in untransfected cells or cells overexpressing RabGEF1-GFP, Rab5-GFP, or the constitutively active Rab5, Rab5Q79L-GFP (Figure 1C,D).

Because RabGEF1 is important for internalization of cross-linked FcϵRI, we next examined whether Rabaptin-5 deficiency influenced FcϵRI internalization.18 FcϵRI internalization rates in shR-treated BMCMCs were no different than in control cells (Figure 1E). More distal Rab5 processes include coordination of trafficking through the early endosome compartment, so we monitored cell uptake of fluorescently labeled BSA molecules. When shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs cells were pulsed for 20 minutes with Alexa 633-BSA, each group internalized similar amounts of BSA, and the associated MFI slightly decreased over time after washout, consistent with Alexa 633 being fairly pH insensitive (Figure S2A). However, when cells were pulsed and washed free of Cy5-BSA, the BMCMC MFI markedly increased over time (Figure 1F). Cy5 is sensitive to internal quenching, and the changes in MFI are probably the result of relief from quenching as BSA molecules unfold when passing to more acidic compartments. Indeed, cells treated with bafilomycin A, to diminish endosomal acidification, exhibited only minimal increases in MFI after washout (Figure 1F). Notably, Rabaptin-5–deficient cells had larger fold increases in MFIs, suggesting that movement through the endolysosomal system is enhanced in the absence of Rabaptin-5. Rabaptin-5 deficiency did not influence mast cell autofluorescence (Figure S2B). These data suggest that Rabaptin-5 has a dispensable or redundant role in canonical Rab5-mediated processes, such as endosome fusion and FcϵRI internalization in mast cells, but may act to regulate endolysosomal trafficking and/or endosomal pH.

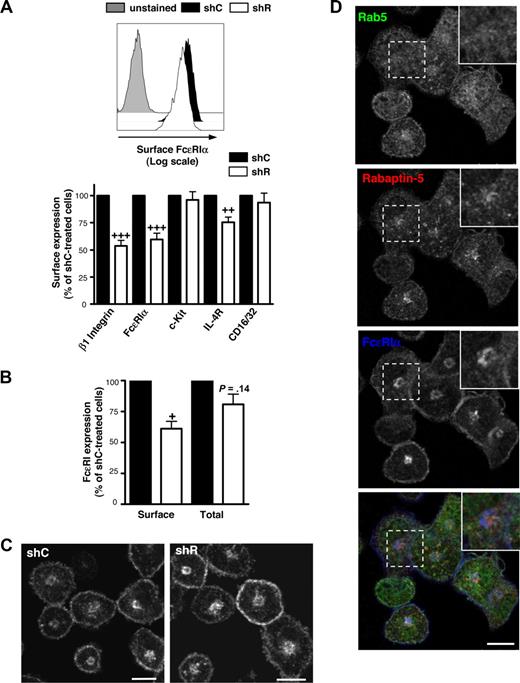

Rabpatin-5 regulates FcϵRI surface expression

Given the correlation between diminished FcϵRI expression and decreased Rabaptin-5 levels in RabGEF1-deficient BMCMCs,18 Rabaptin-5 may be important for regulating surface FcϵRI expression. shR-treated BMCMCs demonstrated a 40% to 50% decrease in surface FcϵRI compared with shC-treated cells (Figure 2A). Rabaptin-5 knock-down reduced surface levels of other receptors expressed on BMCMCs, including the IL-4 receptor and β1 integrin, whereas c-Kit and CD16/32 were unaffected (Figure 2A). These findings show that Rabaptin-5 does not globally alter receptor expression in mast cells but rather is important for surface expression of a subset of receptors.

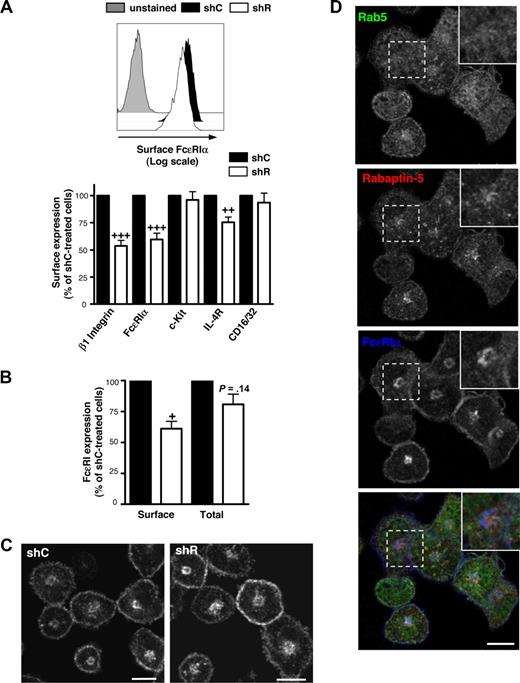

Rabaptin-5 knock-down decreases surface FcϵRIα expression in BMCMCs. (A) Surface FcϵRIα expression was analyzed by flow cytometry on control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) shRNA-treated BMCMCs. Representative histograms comparing control (black filled histogram) and Rabaptin-5-deficient (unfilled histogram) BMCMCs. Gray filled histogram indicates streptavidin only. Bar graph depicts surface expression of the indicated mast cell receptors assayed by flow cytometry, pooled from 5 different pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. (B) Total or surface FcϵRIα levels from control or Rabaptin-5–deficient BMCMCs were analyzed by flow cytometry. Bar graph indicates total FcϵRIα expression relative to shC-treated BMCMCs from 5 separate experiments. (C) The subcellular distribution of FcϵRIα in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs was assessed by confocal microscopy as described in Document S1, “Immunofluorescence.” Bar represents 7.5 μm. (D) Localization of Rab5 (green), Rabaptin-5 (red), and FcϵRIα (blue) was examined in control BMCMCs by confocal microscopy. Magnified images of the regions outlined by dashed boxes are shown in the upper right corner of each panel. Bar represents 7.5 μm. In panels A and B: +P < .05, ++P < .01, +++P < .001, compared with hypothetical value of 100.

Rabaptin-5 knock-down decreases surface FcϵRIα expression in BMCMCs. (A) Surface FcϵRIα expression was analyzed by flow cytometry on control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) shRNA-treated BMCMCs. Representative histograms comparing control (black filled histogram) and Rabaptin-5-deficient (unfilled histogram) BMCMCs. Gray filled histogram indicates streptavidin only. Bar graph depicts surface expression of the indicated mast cell receptors assayed by flow cytometry, pooled from 5 different pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. (B) Total or surface FcϵRIα levels from control or Rabaptin-5–deficient BMCMCs were analyzed by flow cytometry. Bar graph indicates total FcϵRIα expression relative to shC-treated BMCMCs from 5 separate experiments. (C) The subcellular distribution of FcϵRIα in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs was assessed by confocal microscopy as described in Document S1, “Immunofluorescence.” Bar represents 7.5 μm. (D) Localization of Rab5 (green), Rabaptin-5 (red), and FcϵRIα (blue) was examined in control BMCMCs by confocal microscopy. Magnified images of the regions outlined by dashed boxes are shown in the upper right corner of each panel. Bar represents 7.5 μm. In panels A and B: +P < .05, ++P < .01, +++P < .001, compared with hypothetical value of 100.

To assess whether Rabaptin-5 can influence FcϵRI transport to the surface, BMCMCs were fixed and total or surface FcϵRI expression was examined by flow cytometry. Total FcϵRI levels were similar in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs (Figure 2B), whereas surface FcϵRI levels in shR-treated BMCMCs were approximately 40% less than in control cells, suggesting that Rabaptin-5 may cause some intracellular accumulation of FcϵRI. In accord with these findings, we detected no consistent differences between shR- and shC-treated BMCMCs FcϵRI protein levels in total cell lysates as assessed by Western blot (Figure S1A). Further, lower surface FcϵRI levels in shR-treated BMCMCs were not the result of decreased transcription, as FcϵRIα mRNA levels were similar in the presence or absence of Rabaptin-5 (Figure S1B).

Rabaptin-5's putative function is to regulate membrane traffic,21-23 so its absence may perturb FcϵRI subcellular localization. The subcellular distribution of FcϵRI in shC- and shR-treated BMCMCs was not obviously different (Figure 2C), although a large perinuclear accumulation of FcϵRI was evident in both BMCMC groups (accounting for roughly 50%-60% of the total FcϵRI) that did not colocalize well with Rabaptin-5 or Rab5 (Figure 2D). Because FcϵRI is a heterotetramer composed of an α, β, and 2 γ chains, we examined whether the 3 subunits localized similarly within the cell and found that all subunits colocalized to surface and intracellular locations, suggesting that the detected FcϵRIα localization reflects localization of the entire receptor complex (Figure S3A).

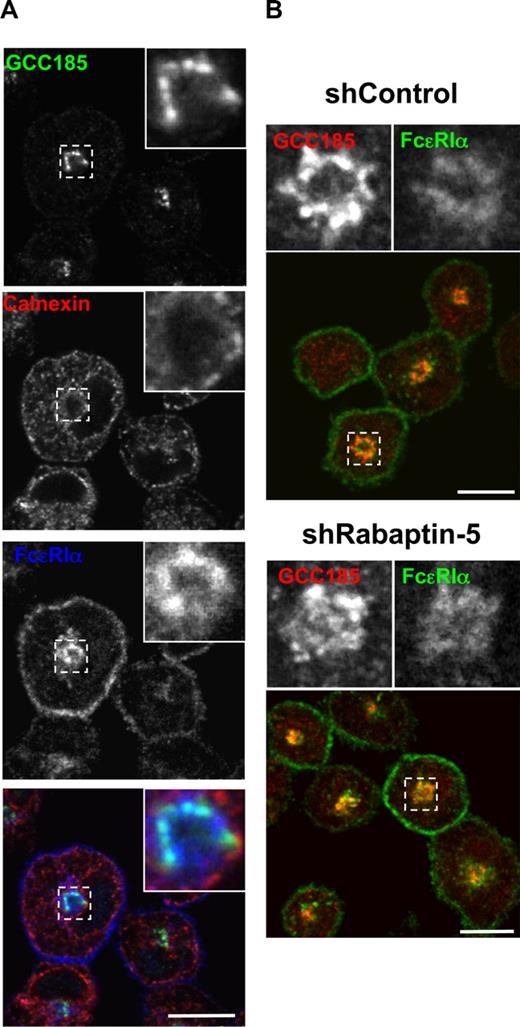

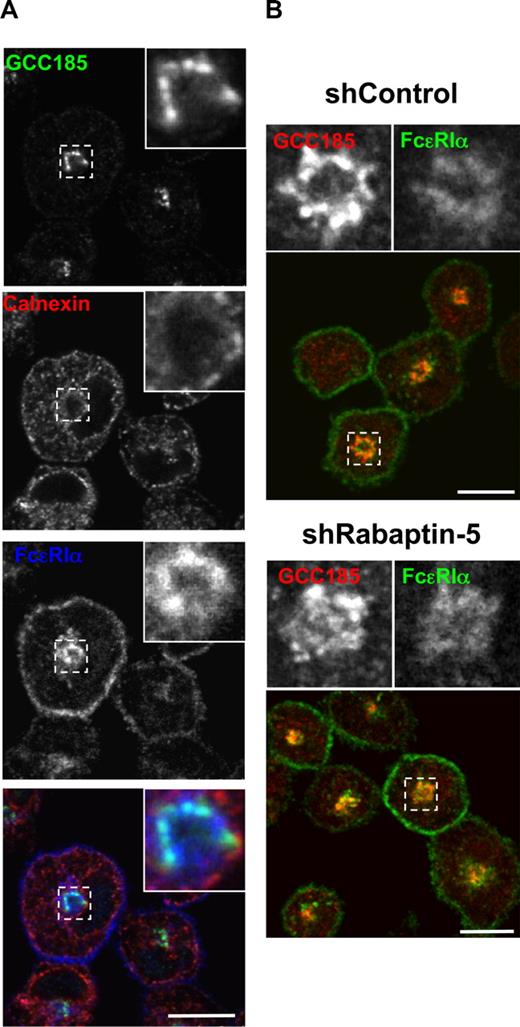

To characterize the intracellular FcϵRI, we examined its distribution relative to a number of markers for the receptor biosynthetic route. Colocalization of FcϵRI with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) marker calnexin was minimal, suggesting that FcϵRIα efficiently exits the ER (Figure 3A); whereas in mast cells treated with BFA, a fungal metabolite that blocks ER to Golgi traffic or in mast cells lacking the FcϵRI γ chain (FcRγ−/− mast cells), FcϵRI accumulated in the ER (Figure S3B,C), consistent with previous findings.30-32 In both control and Rabaptin-5-deficient mast cells, intracellular FcϵRI colocalized with the trans-Golgi marker GCC-185 (Figure 3), suggesting that Rabaptin-5 deficiency does not substantially perturb FcϵRI subcellular localization, and the effect of its absence on levels of surface FcϵRI expression is probably mediated by another mechanism. Although the mechanisms that regulate the efficient exit of FcϵRI from the trans-Golgi remain to be fully elucidated, we found that Rab11 activity contributed to this process (Figure S4).

Rabaptin-5 deficiency does not alter intracellular FcϵRI localization to the trans-Golgi. (A) BMCMCs were processed for confocal microscopy as in Figure 1 and stained with antibodies to calnexin (red; endoplasmic reticulum) and GCC185 (green; trans-Golgi network) to localize intracellular FcϵRI (blue). Magnified regions are outlined by dashed boxes and shown in the upper right corner of each panel. (B) The relative subcellular localization of GCC-185 (green) and FcϵRI (red) was examined in control (shControl) and Rabaptin-5-deficient (shRabaptin-5) BMCMCs. Large panels show overlay of GCC-185 and FcϵRI immunostaining. Magnified images of the regions outlined by dashed boxes are shown in the upper right corner of each panel. Bars represent 7.5 μm.

Rabaptin-5 deficiency does not alter intracellular FcϵRI localization to the trans-Golgi. (A) BMCMCs were processed for confocal microscopy as in Figure 1 and stained with antibodies to calnexin (red; endoplasmic reticulum) and GCC185 (green; trans-Golgi network) to localize intracellular FcϵRI (blue). Magnified regions are outlined by dashed boxes and shown in the upper right corner of each panel. (B) The relative subcellular localization of GCC-185 (green) and FcϵRI (red) was examined in control (shControl) and Rabaptin-5-deficient (shRabaptin-5) BMCMCs. Large panels show overlay of GCC-185 and FcϵRI immunostaining. Magnified images of the regions outlined by dashed boxes are shown in the upper right corner of each panel. Bars represent 7.5 μm.

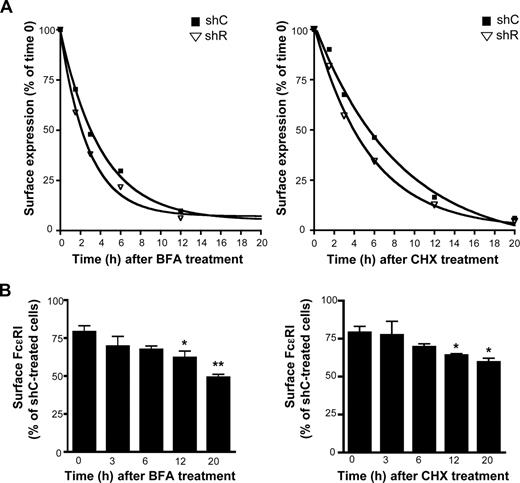

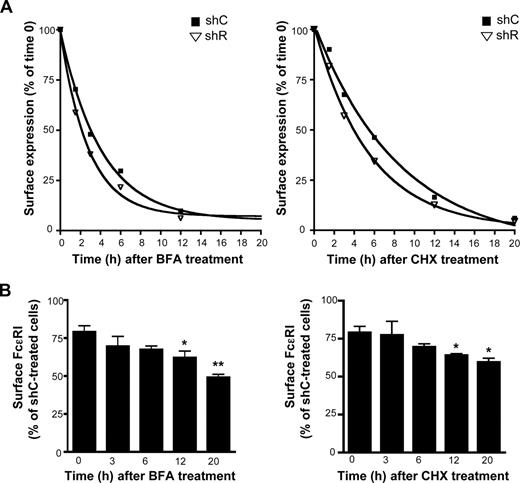

Rabpatin-5 increases FcϵRI half-life

To investigate further the effect of Rabaptin-5 on FcϵRI expression, we examined surface FcϵRI levels by flow cytometry after treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor CHX. Consistent with previous findings,31,33 CHX treatment yielded an FcϵRI half-life of 5.9 hours (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.5-8.5 hours) in shC-treated BMCMCs, whereas shR-treated BMCMCs exhibited a half-life of 3.8 hours (95% CI, 2.8-5.9 hours) when data were fit to an exponential decay formula (Figure 4A). Similarly, in BFA-treated cells, Rabaptin-5 deficiency reduced FcϵRI half-life from 2.8 hours (95% CI, 2.5-3.3 hours) to 1.9 hours (95% CI, 1.6-2.4 hours; Figure 4A). Thus, no matter which approach was used to prevent new receptors from reaching the surface (ie, blocking protein synthesis or exit from the ER), shR-treated BMCMCs were unable to maintain surface FcϵRI as effectively as control cells. Consistent with these data, when the relative levels of FcϵRI on the surface of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs before and after BFA or CHX treatment were compared, the differences between shC- and shR-treated surface FcϵRI increased as time elapsed (Figure 4B), demonstrating that the decreased FcϵRI half-life in shR-treated BMCMCs significantly influences FcϵRI surface levels.

Rabaptin-5 deficiency decreases FcϵRIα half-life. (A) FcϵRIα half-life was measured in control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) shRNA-treated BMCMCs by exposing cells to 100 μg/mL of brefeldin A (BFA), or 1.5 μg/mL of cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times. Surface FcϵRIα was then assessed by flow cytometry. Expression relative to time 0 was calculated for the indicated time points. Data from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs were pooled and fit to exponential decay curves. (B) Bar graph indicates shR-treated BMCMC surface FcϵRIα levels relative to shC-treated BMCMCs at the indicated times from data pooled from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs (*P < .05, **P < .01 by Student t test compared with percentage difference at time 0).

Rabaptin-5 deficiency decreases FcϵRIα half-life. (A) FcϵRIα half-life was measured in control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) shRNA-treated BMCMCs by exposing cells to 100 μg/mL of brefeldin A (BFA), or 1.5 μg/mL of cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times. Surface FcϵRIα was then assessed by flow cytometry. Expression relative to time 0 was calculated for the indicated time points. Data from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs were pooled and fit to exponential decay curves. (B) Bar graph indicates shR-treated BMCMC surface FcϵRIα levels relative to shC-treated BMCMCs at the indicated times from data pooled from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs (*P < .05, **P < .01 by Student t test compared with percentage difference at time 0).

Rabaptin-5 is dispensable for FcϵRI recycling

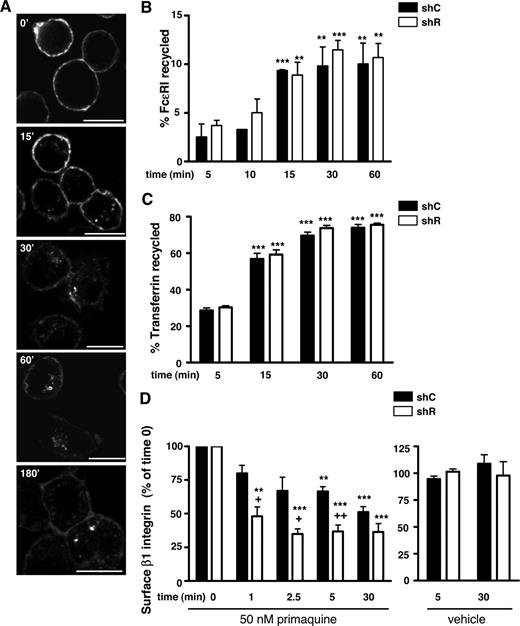

FcϵRI trafficking through a Rabaptin-5 regulated recycling route could explain how Rabaptin-5 influences FcϵRI half-life. Although there is evidence that FcϵRI recycles,31,34 and the recycling of other immunoglobulin (Ig) receptors (Fcγ RI and FcRN) has been measured (recycling half-lives of ∼10 minutes),35,36 we are not aware of such data for FcϵRI recycling. We initially examined whether we could track FcϵRI recycling with monomeric labeled IgE molecules, but we did not detect recycling of IgE-bound FcϵRI complexes. Instead, we found that the IgE-bound FcϵRI complexes that enter the cell often sort to Rab9 (late endosomal/lysosomal) positive compartments (Figure S5). Because IgE can increase FcϵRI expression37,38 by stabilizing FcϵRI on the mast cell surface,31,33 our findings may be relevant to the internalization of such IgE-FcϵRI complexes in vivo but may not necessarily represent what happens to unoccupied or cross-linked FcϵRI.

Given the exquisite sensitivity of FcϵRI to cross-linking and the possibility that unoccupied or cross-linked FcϵRI might follow different trafficking routes, we used α-FcϵRI Fabs (fragment of antigen binding) generated from α-FcϵRIα monoclonal antibodies. BMCMCs exposed to the Fabs at 4°C demonstrated surface Fab localization (Figure 5A) and, within 15 minutes of transfer to 37°C, some of the Fab localized to vesicular structures within the cell (Figure 5A). Notably, no surface membrane clustering, a sign of receptor crosslinking and activation, was observed. When these intracellular Fab-tagged FcϵRI complexes were tracked in real time, they moved rapidly within the cell. Occasional vesicles traveled to and appeared to touch the plasma membrane (data not shown), suggesting that these events may reflect a recycling loop for FcϵRI.

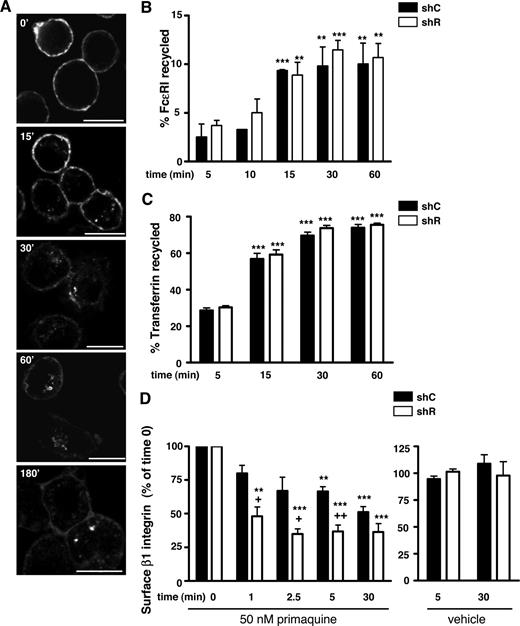

Rabaptin-5 deficiency does not influence FcϵRI recycling but does alter surface stability of β1 integrin. (A) BMCMCs were induced to adhere to fibronectin (FN)-coated coverslips as described in Document S1, “Immunofluorescence,” labeled with Alexa 647-labeled α-FcϵRIα Fabs on ice, transferred to 37°C, and then fixed and processed for confocal microscopy at the indicated times. Bar represents 7.5 μm. (B) FcϵRI recycling was assessed in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs using biotinylated α-FcϵRIα Fabs as described in Document S1, “FcϵRI recycling.” Bar graph represents data pooled from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. (C) Transferrin recycling in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs was performed as described in Document S1, “Transferrin recycling.” Bar graph represents data pooled from 4 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. (D) shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs were exposed to 50 μM of primaquine (left bar graph) or vehicle (right bar graph) for the indicated times, and then surface β1 integrin levels were assessed by flow cytometry. Data were pooled from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. +P < .05; ++P < .01 for shC- versus shR-treated cells; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, versus t = 5 minutes time point (B,C) or time 0 (D).

Rabaptin-5 deficiency does not influence FcϵRI recycling but does alter surface stability of β1 integrin. (A) BMCMCs were induced to adhere to fibronectin (FN)-coated coverslips as described in Document S1, “Immunofluorescence,” labeled with Alexa 647-labeled α-FcϵRIα Fabs on ice, transferred to 37°C, and then fixed and processed for confocal microscopy at the indicated times. Bar represents 7.5 μm. (B) FcϵRI recycling was assessed in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs using biotinylated α-FcϵRIα Fabs as described in Document S1, “FcϵRI recycling.” Bar graph represents data pooled from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. (C) Transferrin recycling in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs was performed as described in Document S1, “Transferrin recycling.” Bar graph represents data pooled from 4 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. (D) shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs were exposed to 50 μM of primaquine (left bar graph) or vehicle (right bar graph) for the indicated times, and then surface β1 integrin levels were assessed by flow cytometry. Data were pooled from 3 separate pairs of shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. +P < .05; ++P < .01 for shC- versus shR-treated cells; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, versus t = 5 minutes time point (B,C) or time 0 (D).

To evaluate mast cells for possible FcϵRI recycling, we loaded BMCMCs with biotinylated Fabs at 37°C for 3 hours to enrich intracellular FcϵRI with biotinylated Fabs. We next assessed the movement of biotinylated Fabs from within to the surface of the cell by examining for increases in cell surface streptavidin binding after free Fabs had been removed from the media so that changes in streptavidin binding reflected FcϵRI recycling. Both shC- and shR-treated BMCMCs exhibited a significant, albeit modest, increases in streptavidin binding that saturated after 30 minutes, suggesting that a small intracellular pool of FcϵRI is mobilized to the cell surface (Figure 5B). However, this should be considered a conservative estimate as FcϵRI may follow a longer recycling route or some FcϵRI may lose the Fab during trafficking. Notably, Rabaptin-5 deficiency did not alter the rate of FcϵRI reappearance, suggesting that Rabaptin-5 is dispensable for FcϵRI recycling (Figure 5B). Further supporting the idea that Rabaptin-5 is not crucial for receptor recycling, we found no differences in transferrin uptake or the rate of transferrin recycling in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs, suggesting that Rabaptin-5 is not critical for transferrin recycling in primary mast cells (Figure 5C), consistent with findings in cell lines.23

Rabaptin-5 stabilizes cell-surface β1 integrin

In the absence of effects on transcription, subcellular localization, and recycling, it is probable that the decreased FcϵRI half-life in shR-treated BMCMCs reflects decreased FcϵRI cell surface stability. If so, other receptors altered by Rabaptin-5 deficiency may have a similar defect in surface stability. β1 integrin recycles with high efficiency in a Rab11-dependent manner in a variety of cell lines39 and is dramatically influenced by the loss of Rabaptin-5 (Figure 2A). We examined β1 integrin levels over time in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs after exposure to vehicle or the endosome maturation/recycling inhibitor, primaquine (PQ). Although PQ rapidly diminished β1 integrin levels by 30 minutes in both shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs, shR-treated BMCMCs had a quicker and more substantial decrease in β1 integrin surface levels (Figure 5D). This finding suggests that, when recycling is inhibited, β1 integrin is removed more efficiently in the absence of Rabaptin-5.

In contrast, FcϵRI surface levels decreased by only 15% to 20% in both shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs 30 minutes after exposure to PQ and returned to baseline by 1.5 hours (Figure S6A). This provides additional evidence that recycling of internalized FcϵRI is minimal and is not influenced by Rabaptin-5. Notably, when new β1 integrin molecules were prevented from reaching the cell surface by exposing cells to CHX or BFA, Rabaptin-5-deficient cells displayed a more precipitous reduction in β1 integrin surface expression over time than did control cells (Figure S6B) as we observed for FcϵRI (Figure 4). Together, these data indicate that Rabaptin-5 is critical for FcϵRI and β1 integrin cell surface stability.

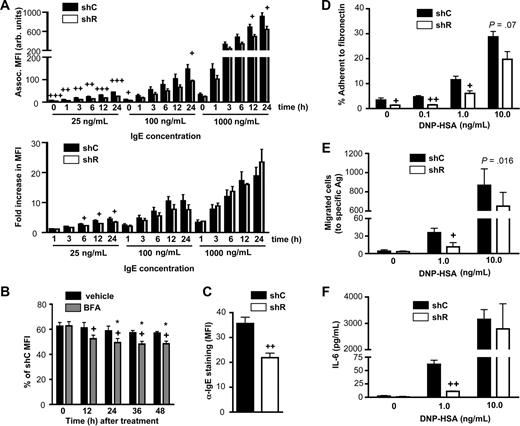

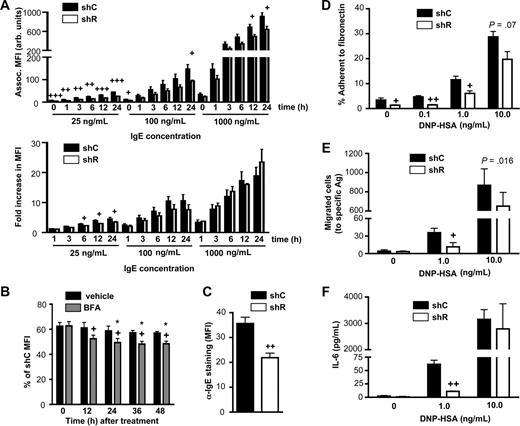

Rabpatin-5 enhances mast cell functional responses to Ag

Do the reduced receptor levels in shR-treated BMCMCs have functional consequences? Activation by specific Ag through FcϵRI requires priming of the cells by IgE binding. We noted significantly less IgE bound to shR-treated BMCMCs after 24-hour culture with a range of IgE concentrations, with the most significant and substantial differences occurring at the lower IgE concentrations (Figure 6A top panel). Notably, the fold increase in IgE association at higher concentrations was not different between shC- and shR-treated BMCMCs (Figure 6A bottom panel), suggesting a similar ability to up-regulate FcϵRI,37,38 probably a result of the stabilizing effects of IgE on surface FcϵRI.31,33 At the lowest IgE concentrations, similar to that in the blood of many subjects with allergic disorders,40 shR-treated BMCMCs (which had lower levels of surface FcϵRI than did shC-treated cells) were less efficient at capturing IgE and up-regulating surface FcϵRI (Figure 6A bottom panel). Even with longer (36- and 48-hour) incubations in the presence of the lowest concentration of IgE, IgE binding continued to be impaired in shR-treated BMCMCs (Figure 6B black bars), a phenomenon that was further accentuated by impairing newly synthesized FcϵRI from reaching the cell surface with BFA treatment (Figure 6B gray bars). To evaluate whether inefficient IgE capture by mast cells observed in vitro also occurs in vivo, we engrafted the peritoneal cavity of genetically mast cell-deficient mice with shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. After 6 weeks in vivo, shR-treated BMCMCs had significantly less surface IgE (∼ 40% less) than did shC-treated BMCMCs (Figure 6C), despite similar percentages of peritoneal mast cells (12.3 ± 1.5 vs 11.16 ± 1.3 peritoneal mast cells, [mean ± SEM] recovered from mice injected with shC- versus shR-treated BMCMCs, respectively).

Rabaptin-5 deficiency diminishes mast cell IgE-dependent responses to specific antigen. (A) Control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) shRNA-treated BMCMCs were cultured with various concentrations of Alexa 647-labeled IgE (IgE-647) for the indicated times and then assessed for associated fluorescence. Top panel bar graph represents total associated fluorescence; bottom panel bar graph, fold increase in associated fluorescence compared with time 0 (incubated for 1 hour at 4°C). (B) shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs were cultured with low amounts of IgE-647 (25 ng/mL) in the presence (gray bars) or absence (black bars) of 100 μg/mL of brefeldin A, and associated fluorescence was assessed at the indicated times. +P < .05 for vehicle versus BFA; *P < .05 versus time 0 in the same treatment group. (C) C57BL/6-KitW−sh/W−sh mice were injected intraperitoneally with GFP+ shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs; 6 weeks later, peritoneal cells were harvested, stained with α-IgE, analyzed by flow cytometry, and MFIs of GFP+ cells were pooled to generate the bar graphs. (D) Ag-induced adhesion to fibronectin (FN) was assessed in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. Cells were sensitized with 1 μg/mL of DNP-specific IgE overnight, washed, and placed in FN-coated wells in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Ag and allowed to adhere for 1 hour. Data were pooled from triplicate determinations and are representative of the similar results that were obtained in each of the 5 experiments that were performed. (E) Migration to Ag through FN-coated transwells was assessed for shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. Cells were prepared as in panel D, then placed in a transwell with the indicated concentrations of Ag and allowed to migrate for 6 hours. Migrated cells were counted by flow cytometry. Data were pooled from duplicate determinations and are representative of similar results that were obtained in the 3 experiments that we performed. (F) IL-6 produced from shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs, prepared as in panel D that were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of Ag for 6 hours; IL-6 was quantified by ELISA. (A,C-F) +P < .05, ++P < .01, +++P < .001 for shC- versus shR-treated cells.

Rabaptin-5 deficiency diminishes mast cell IgE-dependent responses to specific antigen. (A) Control (shC) or Rabaptin-5 (shR) shRNA-treated BMCMCs were cultured with various concentrations of Alexa 647-labeled IgE (IgE-647) for the indicated times and then assessed for associated fluorescence. Top panel bar graph represents total associated fluorescence; bottom panel bar graph, fold increase in associated fluorescence compared with time 0 (incubated for 1 hour at 4°C). (B) shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs were cultured with low amounts of IgE-647 (25 ng/mL) in the presence (gray bars) or absence (black bars) of 100 μg/mL of brefeldin A, and associated fluorescence was assessed at the indicated times. +P < .05 for vehicle versus BFA; *P < .05 versus time 0 in the same treatment group. (C) C57BL/6-KitW−sh/W−sh mice were injected intraperitoneally with GFP+ shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs; 6 weeks later, peritoneal cells were harvested, stained with α-IgE, analyzed by flow cytometry, and MFIs of GFP+ cells were pooled to generate the bar graphs. (D) Ag-induced adhesion to fibronectin (FN) was assessed in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. Cells were sensitized with 1 μg/mL of DNP-specific IgE overnight, washed, and placed in FN-coated wells in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Ag and allowed to adhere for 1 hour. Data were pooled from triplicate determinations and are representative of the similar results that were obtained in each of the 5 experiments that were performed. (E) Migration to Ag through FN-coated transwells was assessed for shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs. Cells were prepared as in panel D, then placed in a transwell with the indicated concentrations of Ag and allowed to migrate for 6 hours. Migrated cells were counted by flow cytometry. Data were pooled from duplicate determinations and are representative of similar results that were obtained in the 3 experiments that we performed. (F) IL-6 produced from shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs, prepared as in panel D that were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of Ag for 6 hours; IL-6 was quantified by ELISA. (A,C-F) +P < .05, ++P < .01, +++P < .001 for shC- versus shR-treated cells.

Having demonstrated that reduced FcϵRI levels on mast cells with reduced levels of Rabaptin-5 resulted in less efficient IgE capture, we investigated whether mast cell functional activation by Ag induced cross-linking of Ag-specific IgE/FcϵRI complexes also was reduced by a deficiency of Rabaptin-5. The adhesion of shR-treated BMCMCs to fibronectin was markedly reduced in unstimulated cells and after low level exposure to specific Ag; whereas at high Ag concentration, differences in adhesion between shC and shR-treated BMCMCs were minimal (Figure 6D). Similarly, in shR-treated BMCMCs, Ag-induced migration (Figure 6E) and IL-6 production (Figure 6F) were significantly impaired at a low Ag concentration, but not a 10-fold higher Ag concentration. These data show that Rabaptin-5 deficiency can substantially alter mast cell sensitivity and responses to Ag, presumably at least in part because of the effects of the Rabaptin-5 deficiency on surface levels of FcϵRI and β1 integrin.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that Rabaptin-5, a Rab5 effector, is important for maintaining surface expression of 2 important receptors in mast cells, FcϵRI and β1 integrin. Contrary to the current thought based on in vitro studies, which have suggested that Rabaptin-5 is necessary to potentiate RabGEF1's activity, the data presented here (Figure 1), our previous findings,18 and the findings of others41 demonstrate that Rabaptin-5 as well as the interaction between Rabaptin-5 and RabGEF1 are not necessary for Rab5 activation, endosome fusion, or receptor internalization. It is possible that extremely low levels of Rabaptin-5 can support these processes or that compensatory mechanisms permit Rab5 activation/function when Rabaptin-5 is not present or when Rabaptin-5 does not interact with RabGEF1/Rabex-5. However, the cellular role of Rabaptin-5 remains enigmatic. Recent data have shown that Rabaptin-5 can interact with other proteins, namely, Rab4,22,23 γ-adaptin,23,42,43 and the GGAs (Golgi-associated γ-adaptin ear containing ARF binding proteins),44-46 raising the possibility that Rabaptin-5 is involved in recycling or endosomal-Golgi traffic.

We found that Rabaptin-5 was dispensable for transferrin recycling (Figure 5C), the prototype for Rab4 recycling. FcϵRI recycling, although minimal, was unaffected by the loss of Rabaptin-5 (Figures 5B, S6A). Furthermore, in our experiments in mast cells, the Rabaptin-5-interacting proteins GGA1 and AP-1 did not appear to be localized abnormally in the absence of Rabaptin-5 (Figure S7), even though others have shown that overexpression of Rabaptin-5 alters the localization of GGA145 and AP-1.23 Our findings, of course, do not exclude the possibility that Rabaptin-5 has a role in protein trafficking between the Golgi and endosomal compartments, but such a role remains to be demonstrated.

However, we did find a definite phenotypic abnormality in cells that lacked Rabaptin-5: Rabaptin-5's absence diminished surface expression of certain BMCMC receptors under baseline conditions, demonstrating that Rabaptin-5 is necessary for maintaining normal levels of expression of these receptors on the cell surface. We found that FcϵRIα transcription (Figure S1B) and transport of FcϵRI to the cell surface were unaffected by the loss of Rabaptin-5; both shC- and shR-treated BMCMCs up-regulated FcϵRI similarly when exposed to excess IgE, thus allowing stabilization of the majority of cell surface delivered FcϵRI (Figure 6A). How then, does a lack of Rabaptin-5 alter levels of receptors on the cell surface?

Rabaptin-5 deficiency decreased FcϵRI half-life in cells incubated without IgE by approximately 30% (Figure 4A). shR-treated BMCMCs also exhibited reduced up-regulation of surface FcϵRI on exposure to low levels of IgE (Figure 6A). At such “suboptimal” IgE levels, many of the surface FcϵRI complexes probably remained unoccupied and may have been removed by a process that is enhanced in the absence of Rabaptin-5. Notably, at higher concentrations of IgE, IgE stabilization of FcϵRI at the cell surface apparently largely compensated for the decreased FcϵRI half-life in shR-treated BMCMCs (Figure 6A), resulting in less pronounced differences in FcϵRI surface levels between shC- and shR-treated BMCMCs. The diminished IgE-binding in shR-treated BMCMCs decreased their sensitivity to Ag (Figure 6D-F), findings that may have reflected altered signal quantity, kinetics, and/or quality.

Mechanisms that might contribute to the effect of Rabaptin-5 deficiency on FcϵRI half-life include enhanced removal or inefficient recycling of the receptor. We found no defect in FcϵRI recycling in the absence of Rabaptin-5 (Figure 5B), leaving enhanced removal as the probable mechanism for the reduced FcϵRI half-life. Consistent with enhanced receptor removal, β1 integrin surface levels diminished faster in shR-treated BMCMCs exposed to PQ than in the corresponding shC-treated cells (Figure 5D). In support of Rabaptin-5 being a regulator of receptor expression, Deneka et al23 found that HeLa cells treated with Rabaptin-5 RNAi were markedly deficient in transferrrin uptake, which the authors attributed to problems with receptor internalization. An alternate explanation is that the reduced transferrin uptake may reflect reduced surface transferrin receptor levels, a phenomenon that was not specifically investigated.23 In our system, primary mast cells expressed very low levels of the transferrin receptor, so it was difficult to assess reliably any potential differences in surface expression of the receptor between control and Rabaptin-5-deficient mast cells.

Rabaptin-5 deficiency did not alter the intracellular distribution of a large trans-Golgi pool of FcϵRI (Figures 2C, 3B), arguing against the possibility that Rabaptin-5 causes misrouting of FcϵRI. However, Rabaptin-5-deficient mast cells may have exhibited a slight intracellular accumulation of FcϵRI, as suggested by low levels of surface FcϵRI expression (Figure 2B) in the presence of similar levels of total FcϵRI (Figures 2B, S1A) in shR- versus shC-treated BMCMCs. Although it is possible that this may reflect a slight increase in FcϵRIα mRNA levels in the absence of Rabaptin-5 (Figure S1B), that difference did not achieve statistical significance.

Our data reveal a novel and unpredicted function for Rabaptin-5 in increasing surface half-life of FcϵRI and β1 integrin. However, the mechanism by which Rabaptin-5 enhances the surface half-life of these receptors is not clear. It is doubtful that Rabaptin-5 regulates Rab5 by altering the localization of either RabGEF1 or Rab5 because we found no obvious differences in the localization of RabGEF1-GFP, Rab5-GFP, or endogenous Rab5 in shC- or shR-treated BMCMCs (Figure 1B,C). Furthermore, diminished surface levels of FcϵRI and β1 integrin were present in RabGEF1-deficient cells (which are also deficient in Rabaptin-5), decreasing the likelihood that Rabaptin-5's effects are mediated through RabGEF1.18

Rabaptin-5 may regulate Rab5 activation directly or regulate FcϵRI and β1 integrin trafficking generally. In support of Rabaptin-5 regulating Rab5 directly, Horiuchi et al found that recombinant Rabaptin-5 actually suppressed endosome fusion in vitro, suggesting that Rabaptin-5, when not complexed to RabGEF1, inhibits Rab5 activity.29 Our findings are consistent with such a regulatory role for Rabaptin-5. Both control and Rabaptin-5–deficient mast cells internalized BSA molecules to a similar extent (Figure S2A). However, using a Cy5-BSA that was susceptible to internal quenching (and that is relieved from quenching during endosome maturation/acidification), we found that Rabaptin-5–deficient cells demonstrated a larger increase cell associated Cy5 fluorescence (Figure 1F). This finding suggests that endosome acidification/maturation is enhanced in the absence of Rabaptin-5. Although these preliminary data suggest that Rabaptin-5 regulates endosomal trafficking kinetics of fluid phase markers, a definitive mechanism for Rabaptin-5 in this process remains to be established. Rabaptin-5 cleavage has been proposed as a mechanism that can disrupt the endosome compartment during apoptosis.47-49 Although we found no differences in the viability of mast cells in standard culture media, Rabaptin-5–deficient BMCMCs were more susceptible to apoptosis after growth factor withdrawal (Figure S8). Future studies will be required to characterize in detail Rabaptin-5's role in cell survival.

In conclusion, we identified a novel role for Rabaptin-5 in increasing the surface stability of important mast cell receptors and provided evidence that these changes contributed to the significant functional abnormalities observed in Rabaptin-5–deficient mast cells. The finding of diminished surface expression of FcϵRI in Rabaptin-5–deficient mast cells is particularly important given the immunologic relevance of this receptor in allergic disorders and host defense. Some patients with moderate or severe asthma benefit from treatment with α-IgE, which reduces circulating IgE, IgE-dependent mast cell activation, and allergic inflammation.50,51 The data presented here are consistent with other evidence52,53 in suggesting that direct targeting of FcϵRI also represents a promising approach for dampening unwanted mast cell activation. Importantly, a better understanding of the regulation of FcϵRI trafficking and surface expression regulation may provide insights about additional therapeutic alternatives. Our findings also highlight the incomplete knowledge about the Rab5 pathway. We provide evidence that, contrary to expectations, Rabaptin-5 is not necessary for canonical RabGEF1 activation of Rab5 or Rab5 processes in mast cells but instead may have a role in endosomal trafficking.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Satoshi Nunomura for preparing the FcϵRI Fabs, M. Tsai and S.-Y. Tam for critical reviews of the manuscript, other members of the Galli laboratory for helpful discussions, and M. Liebersbach for animal husbandry.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD; grants AI23990, AI070813, CA72074, and HL67674 to S.J.G.) and Stanford Medical Scientist Training Program (grant 5-732-GM07365 to E.J.R.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: E.J.R. designed and performed the research, collected, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; A.M.P. performed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript; C.R. provided materials and edited the manuscript; and J.K. and S.J.G. analyzed and interpreted the data and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen J. Galli, Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305-5324; e-mail: sgalli@stanford.edu.