Abstract

BACKGROUND: Extramedullary acute leukemias (EM AL) following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) are rare, but devastating events. Little is known about their incidence (0.05% to 30% according to registry data and small series, respectively), biology (sanctuary sites? uneven graft-versus-leukemia efficacy?), risk factors (acute myeloid leukemia, AML, with FAB M4 or M5? Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia, ALL? conditioning with busulfan?), treatment, and outcome. Our purpose was to compare clinical features and outcome of EM AL occurring prior to and after allo-SCT in a large cohort of patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: In this single center, retrospective analysis, we report on 350 consecutive patients who received an allo-SCT for acute leukemias at our institution in the decade between January 1998 to December 2007, allowing for at least six months of follow-up until July 2008. 160 were females and 190 males, with a median age of 48 years (range: 17 to 71). 191 had been diagnosed with de novo AML, 78 with AML secondary after myelodysplasia or myeloproliferative disease (sAML), and 81 with ALL. According to molecular, cytogenetic and response criteria, 47 were considered standard and 303 high risk patients. 118 of 350 patients (34%) suffered a relapse after allo-SCT.

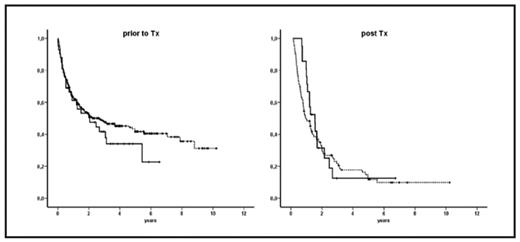

RESULTS: Of the 350 patients, 42 (12%) had extramedullary manifestations prior to allo- SCT: 20 within the central nervous system (CNS), 16 cutaneous or lymphonodular, 2 musculoskeletal, and 4 urogenital manifestations. 21 of 350 patients (6%; 13 AML, 6 ALL, 2 sAML) had EM AL relapses after allo-SCT: 8 CNS, 6 cutaneous or lymphonodular, 5 musculoskeletal, and 2 urogenital; EM relapses were associated with marrow recurrences in 11 of 21 patients. However, there was little overlap between the EM AL groups prior to and after allo-SCT: only 6 patients belonged to both groups, and only 3 patients actually relapsed in the same EM compartment as before allo-SCT. After a median follow-up of 16 months (range: 0 to 122), survival probabilities at 5 years were 42% for patients without EM AL compared to 34% for EM AL patients prior to allo-SCT (not significant), and 12% for all acute leukaemia relapses versus 13% for EM AL patients after allo-SCT (not significant). For the latter, factors associated with adverse outcome included: no complete remission at allo-SCT (p = 0.081), reduced intensity conditioning (p = 0.034), prior donor lymphocyte infusions (DLI) (p = 0.034), and relapse within the first year after allo- SCT (p = 0.0017). Conversely, gender, age, diagnosis, AML FAB subtype, Philadelphia chromosome positive ALL, EM AL before allo-SCT, busulfan as part of the conditioning regimen, donor status, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match, and graft-versus-hostdisease (GvHD) before EM relapse did not play a significant role for survival of patients with EM AL after allo-SCT.

CONCLUSION: In this largest single-center study to date, extramedullary acute leukemias occured quite frequently both prior to and after allo HSCT. Patients with or without EM AL had comparable outcomes, both in continuous remission or relapse. Since EM AL occurred at identical sites in different patients prior to or after allo-SCT, and since some patients with EM AL after allo-SCT are cured due to a graft-versus-leukemia effect, the concept of “disease sanctuaries” seems unlikely. We speculate that temporo-spatial changes in immune surveillance might be mechanisms involved. Local blast control, e.g. through radiation, and systemic chemotherapeutic as well as immunomodulatory approaches may help to improve the prognosis of patients with EM AL both prior to and after allo-SCT.

Kaplan-Meier-curves for overall survival: (prior to Tx): 308 patients without EM AL (dotted line) versus 42 patients with EM AL (solid line) (post Tx): 97 patients without EM AL relapse (dotted line) versus 21 patients with EM AL relapse (solid line)

Kaplan-Meier-curves for overall survival: (prior to Tx): 308 patients without EM AL (dotted line) versus 42 patients with EM AL (solid line) (post Tx): 97 patients without EM AL relapse (dotted line) versus 21 patients with EM AL relapse (solid line)

Disclosures: No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Corresponding author