Abstract

The Lutheran (Lu) and Lu(v13) blood group glycoproteins function as receptors for extracellular matrix laminins. Lu and Lu(v13) are linked to the erythrocyte cytoskeleton through a direct interaction with spectrin. However, neither the molecular basis of the interaction nor its functional consequences have previously been delineated. In the present study, we defined the binding motifs of Lu and Lu(v13) on spectrin and identified a functional role for this interaction. We found that the cytoplasmic domains of both Lu and Lu(v13) bound to repeat 4 of the α spectrin chain. The interaction of full-length spectrin dimer to Lu and Lu(v13) was inhibited by repeat 4 of α-spectrin. Further, resealing of this repeat peptide into erythrocytes led to weakened Lu-cytoskeleton interaction as demonstrated by increased detergent extractability of Lu. Importantly, disruption of the Lu-spectrin linkage was accompanied by enhanced cell adhesion to laminin. We conclude that the interaction of the Lu cytoplasmic tail with the cytoskeleton regulates its adhesive receptor function.

Introduction

There is mounting interest in the 2 Lutheran (Lu) red cell transmembrane glycoprotein isoforms that serve as receptors for extracellular matrix laminins. Current evidence indicates that Lu-laminin binding contributes to sickle cell vaso-occlusion.1-5 Lu-dependent sickle red blood cell adhesion appears to involve epinephrine and cyclic adenosine monophosphate activation, supporting the novel concept that inside-out signaling mechanisms may activate red cell adhesion molecules.6 Moreover, polycythemia vera red blood cells (RBCs) demonstrate increased adherence to vascular endothelium also mediated by Lu-laminin binding, suggesting that this interaction may contribute to the increased thrombosis observed in this myeloproliferative disorder.7 Lu first appears on the erythroblast surface late in differentiation,8 and circulating erythrocytes express 1500 to 4000 copies per cell.9,10 However, Lu expression is not limited to red cells; the isoforms are also present on vascular endothelial cells and epithelial cells in multiple tissues.11 Intriguing recent data show that Lu expression is enhanced in various carcinomas and during malignant transformation of epithelial cells, pointing to a possible role in cancer biology.12-15 To better understand Lu receptor function(s) in both normal and pathologic states, we are investigating the structural interactions of these transmembrane proteins.

The 2 Lu isoforms (85 and 78 kDa)16 are members of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF).11 The 85-kDa Lu glycoprotein contains 5 disulfide-bonded extracellular IgSF domains, a single hydrophobic membrane span, and a cytoplasmic domain of 59 residues.11 Its cytoplasmic tail may function in intracellular signaling and polarization to plasma membrane, as suggested by the presence of the consensus motif for binding of Src homology 3 (SH3) domains, 5 potential phosphorylation sites,11 and a dileucine motif responsible for regulating basolateral localization of Lu in polarized epithelial cells.17 The 78-kDa isoform (termed Lu(v13)18 or B-CAM13 ), generated by alternative splicing of intron 13, differs from the larger form by having a truncated cytoplasmic tail lacking the proline-rich SH3-binding domain, the dileucine motif, and the 5 phosphorylation sites.18 Erythrocyte membranes contain 5- to 10-fold more Lu than Lu(v13).17

Extracellular matrix laminins, a large family of heterotrimeric proteins each composed of 3 polypeptide chains (α, β, and γ),19 perform key roles in adhesion, migration, cell differentiation, and proliferation. We and others have shown that both Lu isoforms bind specifically and with high affinity to laminin proteins containing the α5 polypeptide chain (laminins 511 and 521; as numbered by Aumailley et al20 ).1,5,21,22 We have also determined that the laminin binding site is present in the 3 membrane distal IgSF domains22 and is located at the flexible junction of Ig domains 2 and 3.23

Interactions of receptor molecule cytoplasmic domains with the cytoskeleton can play critical roles in regulating receptor function. Earlier we determined that Lu has a high degree of connectivity to the erythrocyte membrane cytoskeleton.22 A more recent study demonstrated that Lu isoforms directly bind to spectrin, a major constituent of the membrane cytoskeleton.24 Spectrin, which exists in the cell as an α2β2 tetramer, has the form of a long, flexible rod, with a contour length of 200 nm.25-27 The protein is characterized by a succession of repeating units (21 in the α-spectrin chain, and 16 in the β-chain), each of approximately 106 residues, folded into a left-handed, antiparallel triple helical coiled-coil structure.28-30 Such repetitive structure is a basic feature of the spectrin superfamily of proteins, including spectrin, α-actinin, dystrophin, and utrophin.31,32

Although the RK573-574 motif in the Lu and Lu(v13) C-terminal cytoplasmic tails has been identified as the element required for attachment to erythroid spectrin,24 the Lu binding site in spectrin has not been delineated. More importantly, the consequences of the Lu-spectrin association have not been explored. The current study was undertaken as a structural and functional analysis of the Lu-spectrin interaction. We have localized the Lu and Lu(v13)-binding site in spectrin to one single repeat in the α spectrin chain and showed that disruption of the Lu-spectrin interaction in situ resulted in a weakened linkage of Lu to the cytoskeleton and enhanced adhesion of red cells to laminin. These findings indicate that the Lu-spectrin interaction modulates the adhesive activity of Lu.

Methods

Materials

Primers used in polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were from Operon Biotechnologies (Huntsville, AL). pGEX-4T-2 vector and glutathione-Sepharose 4B were purchased from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Restriction enzymes were from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). Laminin purified from human placenta, reduced form glutathione, and isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Streptavidin agarose was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The CM5 biosensor chip, amino coupling kit, and other reagents for surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay were purchased from BIAcore AB (Uppsala, Sweden). The synthetic biotin-labeled cytoplasmic tail of Lu(v13) (CVRRKGGPCCRQRREKGAP) was synthesized and purified at the Core Facility of New York Blood Center. The mass of the peptide was confirmed by mass spectrometric analysis. Polyclonal antibodies specific for human spectrin and glycophorin C (GPC), and the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) and histidine (His) tags were generated in rabbits and affinity purified in our laboratory at the New York Blood Center. Antihuman Lu antibody BRIC 221 was generated in our laboratory at Bristol Institute for Transfusion Sciences. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated antirabbit IgG was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Tetramethylbenzidine microwell peroxidase substrate was the product of Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories (Gaithersburg, MD). Renaissance chemiluminescence detection kit was from Pierce Chemical (Rockford, IL). Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) and GelCode staining reagent from Pierce Chemical; 96-well microplates were from BD Biosciences Discovery Labware (Bedford, MA).

Construction of recombinant proteins

GST-tagged spectrin fragments and spectrin single repeats were constructed and characterized previously.33,34 His-tagged repeat 3 of α-spectrin (αR3), repeat 4 of α-spectrin (αR4), and repeat 5 of α-spectrin (αR5) were subcloned into pET28b+ vector using NcoI and XhoI upstream and downstream, respectively. The cytoplasmic domain of Lu was amplified by PCR using full-length Lu cDNA as template and subcloned into pGEX-4T-2 vector using restriction enzymes EcoRI and SalI upstream and downstream, respectively. The fidelity of the constructs was confirmed by sequencing.

Preparation of proteins

Spectrin was purified from human erythrocytes as described previously.35 The blood was obtained from the New York Blood Center from freshly collected units that were not suitable for transfusion. The GST-fusion polypeptides were purified using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity column, and the His-tagged α-spectrin single repeats were purified using a Nickle column. The purified proteins were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) and clarified by ultracentrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined using extinction coefficients calculated from the tryptophan and tyrosine contents, taking the molar extinction coefficients of these amino acids at 280 nm as 5500 and 1340, respectively.36

Pull-down assays

To measure the binding of recombinant spectrin fragments to the biotin-labeled Lu(v13) peptide, GST-tagged spectrin fragments were incubated with the peptide at room temperature for 1 hour. Streptavidin beads were added to the reaction mixture, incubated for 10 minutes, pelleted, and washed. The pellet was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-GST antibody. To measure the binding of His-tagged α-spectrin single repeat to GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu, the GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu was coupled to glutathione beads at room temperature for 30 minutes. Beads were pelleted and washed. His-tagged αR3, αR4, or αR5 was added to the GST-Lu–conjugated beads in a total volume of 100 μL. The final concentrations of both coupled polypeptide and polypeptides in solution were 1 μM. The mixture was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, pelleted, and washed. The pellet was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the binding was detected by Western blotting using anti-His antibody.

ELISA

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used for inhibition experiments. To examine the inhibition of Lu-spectrin binding by αR4, spectrin (200 ng in 100 μL) was coated onto a 96-well plate overnight at 4°C. The plate was washed and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS plus 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T) for 1 hour at room temperature; 0.1 μM GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu (which was preincubated with increasing concentrations of αR4 or αR5 as negative control) was added to the spectrin-coated plate and incubated for 30 minutes. After 30 minutes of further incubation, the plate was washed and the Lu binding to spectrin was detected by anti-GST antibody followed by HRP-conjugated antirabbit IgG. The color was developed by adding tetramethylbenzidine microwell peroxidase substrate and read by an ELISA plate reader at 450 nm. Similar experiments were performed to examine the effect of αR4 on Lu(v13)-spectrin binding. In this case, Lu(v13) peptides were coated onto the 96-well plate, and αR4 (at increasing concentrations) was added to the Lu(v13) peptide-coated plate and incubated for 30 minutes before spectrin (at a concentration of 0.1 μM) was added. Spectrin binding was detected by antispectrin antibody followed by HRP-conjugated antirabbit IgG as described above in this paragraph.

SPR assay

SPR assay was performed using a BIAcore 3000 instrument (BIAcore). Spectrin or αR4 was covalently coupled to a CM-5 biosensor chip using an amino coupling kit. The instrument was programmed to perform a series of binding assays with increasing concentrations of analyte over the same regenerated surface. Lu(v13) cytoplasmic domain was injected onto a spectrin or αR4 coupled surface. Binding reactions were done in HBS-EP buffer, containing 20 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 0.05% (vol/vol) surfactant P20. The surface was regenerated with 0.05% SDS before each new injection. Sensograms (plots of changes in Response Unit [RU] on the surface as a function of time) derived were analyzed using the software BIAeval 3.0. Affinity constants were estimated by curve fitting using a 1:1 binding model.

Introduction of αR4 into erythrocyte ghosts

Blood was taken from normal adults with informed consent using a New York Blood Center Institutional Review Board–approved protocol in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Red cells were isolated by centrifugation, followed by 3 washes with Tris-buffered isotonic saline (0.15 M potassium chloride, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4). For detergent extractability experiments, polypeptide was introduced into ghosts as follows: cells were lysed and washed 3 times with 35 volumes of ice-cold hypotonic buffer (5 mM Tris, 5 mM potassium chloride, pH 7.4). Under gentle mixing, the ghosts were incubated with various concentrations of the polypeptides in the cold for 10 minutes; 0.1 volume of 1.5 M potassium chloride, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, was added to restore isotonicity, and the ghosts were incubated for another 40 minutes at 37°C to allow resealing. For adhesion assay, introduction of GST, GST-tagged αR4, or GST-tagged αR5 into erythrocytes was performed as previously described by the dialysis method.37

Triton extraction of erythrocyte ghosts

Resealed ghosts (60 μL) were washed 3 times with PBS. The pellet was suspended in 500 μL extraction buffer (5 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, in the presence of 0.05% Triton X-100 for Lu glycoprotein extraction, or 0.5% Triton X-100 for GPC extraction) and incubated on ice for 1 hour, followed by centrifugation at 14 000 rpm (Benchtop centrifuge) for 10 minutes. The pellet was suspended in 60 μL PBS plus 60 μL sample buffer; 14 μL of sample was run on 10% SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using antibodies against Lu and GPC.

Adhesion assay

Purified laminin from human placenta was diluted in PBS and coated on a 96-well microplate at 4°C overnight. The wells were washed with PBS and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at 37°C. Adhesion assays were performed using a gravity driven reverse suspension assay. For this assay, erythrocytes were resealed with different concentrations of GST, GST-αR5, or GST-αR4 polypeptides. The resealed cells were washed 4 times in PBS and diluted to 5 × 105 cells/mL, and then 100 μL (5 × 104 cells) was added to each well. After 1-hour incubation at 37°C, the wells were filled with PBS and the microplate was floated upside down1,38 for 40 minutes in a PBS solution before microscopic observation and cell counting. The cells were quantified in 3 areas at the center of the well by microscopy (×10) using a computerized image analysis system (LSM Image Browser). The area per field was 53 061 μm2. The counted cells were then averaged and presented in terms of fold change.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot

SDS-PAGE was performed using 10% acrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. The blocking was done either overnight at 4°C or for 1 hour at room temperature in blocking buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM of NaCl, 0.5% Tween-20, 5% nonfat dry milk). All other steps were performed at room temperature. The blot was probed for 1 hour with the primary antibody followed by secondary antibody coupled to HRP. After several washes, the blot was developed using the Renaissance Chemiluminescence Detection Kit.

Results

Mapping the Lu and Lu(v13)-binding site in spectrin

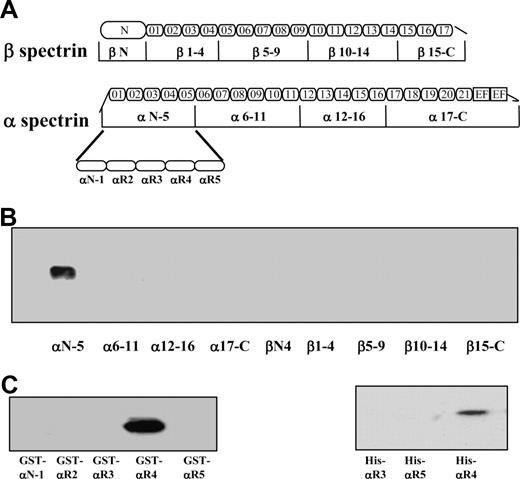

It has been previously shown that spectrin binds to the cytoplasmic domain of both Lu and Lu(v13) isoforms. The only difference between the 2 isoforms is that Lu(v13) has a truncated cytoplasmic tail at the very C terminus; the cytoplasmic domain of Lu contains 59 amino acids, whereas that of Lu(v13) has only the first 20 amino acids. Because the RK573-574 motif identified necessary for binding to spectrin is present in both Lu and Lu(v13) C-terminal cytoplasmic tails, we used biotin-labeled Lu(v13) to study its interaction with spectrin fragments. Binding of 9 recombinant GST-tagged spectrin fragments, encompassing the full length of both α- and β-spectrin chains (Figure 1A), to biotin-labeled Lu(v13) peptide was examined using a streptavidin pull-down assay. As shown in Figure 1B, only one α-spectrin fragment, αN-5, but none of the other 8 spectrin fragments was brought down with Lu(v13). Furthermore, among the separate structural elements that constitute the αN-5 fragment, only one single repeat, αR4, specifically bound to Lu(v13) (Figure 1C). To confirm the αR4 also binds to the cytoplasmic region of Lu, we constructed His-tagged αR3, αR4, and αR5 and examined their binding to GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu by GST pull-down assay. Figure 1D shows that αR4, but not αR3 or αR5, was brought down by Lu. We conclude that, among the 36 repeats of α- and β-spectrin, there is a single binding site for Lu and Lu(v13), and this lies in the αR4 repeat of the α-chain.

Binding of recombinant spectrin fragments and spectrin single repeats to Lu(v13) and Lu. (A) Schematic presentation of recombinant spectrin fragments. The boundaries of all spectrin fragments and single repeats were defined by SMART annotations. (B) Nine GST-tagged spectrin fragments were incubated with biotin-labeled Lu(v13) peptide, and binding was detected with anti-GST antibody. Only α N-5 was brought down. (C) The GST-tagged single repeats within α N-5 fragment were incubated with biotin-labeled Lu(v13) peptide, and the binding was detected as described for panel B. Only αR4 was brought down. (D) The His-tagged single repeats were incubated with GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu, and the binding was detected with anti-His antibody. Only αR4 was brought down.

Binding of recombinant spectrin fragments and spectrin single repeats to Lu(v13) and Lu. (A) Schematic presentation of recombinant spectrin fragments. The boundaries of all spectrin fragments and single repeats were defined by SMART annotations. (B) Nine GST-tagged spectrin fragments were incubated with biotin-labeled Lu(v13) peptide, and binding was detected with anti-GST antibody. Only α N-5 was brought down. (C) The GST-tagged single repeats within α N-5 fragment were incubated with biotin-labeled Lu(v13) peptide, and the binding was detected as described for panel B. Only αR4 was brought down. (D) The His-tagged single repeats were incubated with GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu, and the binding was detected with anti-His antibody. Only αR4 was brought down.

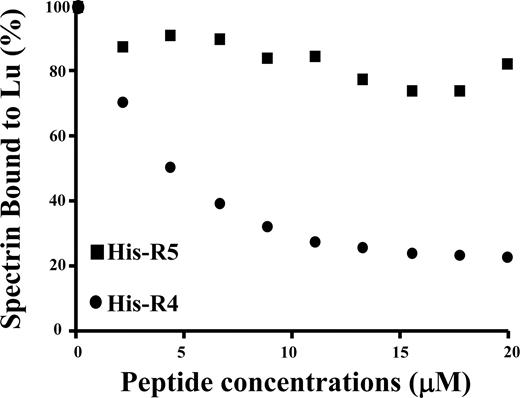

αR4 inhibits binding of full-length spectrin to the cytoplasmic domain of Lu and Lu(v13)

To further confirm the specificity of the interaction between spectrin and Lu as well as Lu(v13), we performed a competitive inhibition assay. In this study, the cytoplasmic domain of Lu was preincubated with increasing concentrations of αR4 before adding to microtiter plates precoated with full-length spectrin. As shown in Figure 2, binding of the Lu cytoplasmic domain to spectrin was progressively diminished with increasing concentrations of αR4. In contrast, αR5 was without effect. αR4 also inhibited the interaction between the cytoplasmic domain of Lu(v13) and spectrin in a concentration-dependent manner (data not shown).

Inhibition of Lu-spectrin interaction by αR4. GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu was preincubated with increasing concentrations of His-tagged αR4 or His-tagged αR5 at room temperature for 30 minutes. Then the mixtures were added to the 96-well plate coated with spectrin. The binding of GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu was detected by anti-GST antibody. Note the progressive decrease of Lu binding to spectrin with the increasing concentrations of αR4 but not with αR5.

Inhibition of Lu-spectrin interaction by αR4. GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu was preincubated with increasing concentrations of His-tagged αR4 or His-tagged αR5 at room temperature for 30 minutes. Then the mixtures were added to the 96-well plate coated with spectrin. The binding of GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of Lu was detected by anti-GST antibody. Note the progressive decrease of Lu binding to spectrin with the increasing concentrations of αR4 but not with αR5.

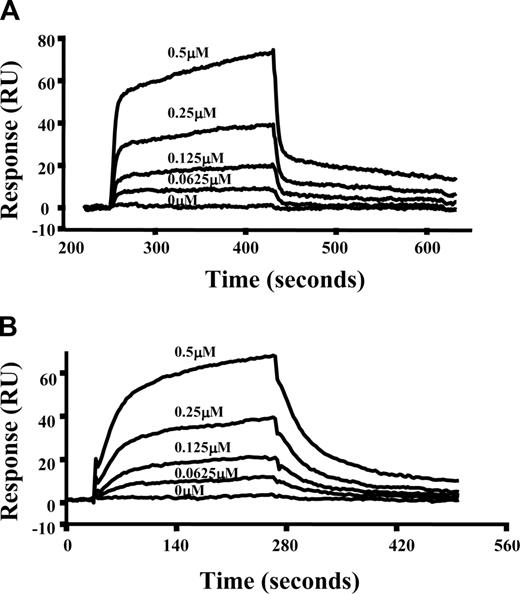

Kinetic analysis of interactions between spectrin and its fragments with Lu(v13) as assessed by SPR assay

To further characterize the interactions of spectrin with Lu(v13), we used a real-time plasmon resonance assay. Because both Lu isoforms contain the spectrin binding motif and our results in the previous section show that they behave the same in terms of binding to spectrin as well to αR4, we chose to measure interactions of Lu(v13) to spectrin and αR4 using SPR assay. In these experiments, full-length spectrin or GST-tagged αR4 fragment was immobilized on the surface of a sensor chip and the binding of Lu(v13) was assessed. Figure 3 demonstrates the dose-dependent binding of Lu(v13) to spectrin and αR4, respectively. The binding affinity for Lu(v13)-spectrin interaction is 2.3 μM, which is consistent with Kroviarski et al24 who showed that GST-Lu and GST-Lu(v13) bound to spectrin, with affinities of 3.4 μM and 2.7 μM, respectively. Of important note, we observed that the binding affinity between Lu(v13) and αR4 is also in the μM range (8.3 μM).

Interaction of spectrin or αR4 with Lu(v13) as assessed by surface plasmon resonance assay. Spectrin or GST-αR4 was immobilized onto CM5 sensor chip. Lu(v13) peptide at different concentrations (0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μM) was injected at 20 μL/min over the surface in a BIAcore 3000 instrument. The figure shows dose-response curves of Lu(v13) binding to immobilized spectrin (A) or to immobilized GST-αR4 (B).

Interaction of spectrin or αR4 with Lu(v13) as assessed by surface plasmon resonance assay. Spectrin or GST-αR4 was immobilized onto CM5 sensor chip. Lu(v13) peptide at different concentrations (0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μM) was injected at 20 μL/min over the surface in a BIAcore 3000 instrument. The figure shows dose-response curves of Lu(v13) binding to immobilized spectrin (A) or to immobilized GST-αR4 (B).

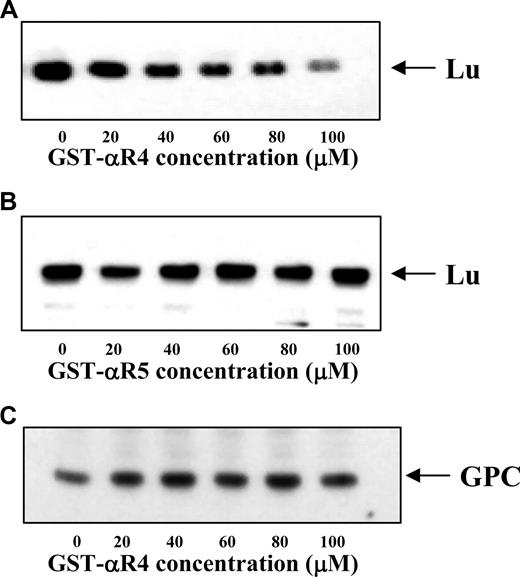

Effect of incorporation of αR4 into red cell ghosts on Lu extractability

Having identified αR4 as the attachment site for Lu to spectrin and demonstrated inhibition of the Lu-spectrin interaction by αR4 in vitro, we then examined the effect of disrupting the Lu-spectrin interaction on the linkage of Lu to the cytoskeleton in situ. For this, we resealed the GST-αR4 or GST-αR5 polypeptide into erythrocytes. The association of Lu to the cytoskeleton was assessed by determining its extractability in the presence of non ionic detergent. Figure 4A shows that, with increasing concentrations of GST-αR4, the amount of Lu retained in the cytoskeletal fraction was progressively diminished. Once again, GST-αR5 had no effect (Figure 4B). Moreover, the retention of glycophorin C (which is linked to the cytoskeleton by protein 4.1R) in the cytoskeletal fraction remained unchanged in the presence of increasing concentrations of GST-αR4 (Figure 4C). These data demonstrate that αR4 specifically disrupted the Lu-spectrin interaction, resulting in enhanced liberation of Lu from the cytoskeleton on exposure to detergent. Our findings clearly indicate that disruption of the Lu-spectrin interaction in situ results in a weakened linkage of Lu to the cytoskeleton.

Immunoblot of Lu and GPC in Triton shells prepared from resealed red cell ghosts. The Triton shells were prepared from ghosts resealed without or with increasing concentrations of αR4 or αR5 as described in “Triton extraction of erythrocyte ghosts.” Proteins retained in the Triton shells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Lu and anti-GPC. Note the progressive decrease of Lu in αR4-resealed ghosts (A) but not αR5-resealed ghosts (B). GPC was unchanged in αR4-resealed ghosts (C).

Immunoblot of Lu and GPC in Triton shells prepared from resealed red cell ghosts. The Triton shells were prepared from ghosts resealed without or with increasing concentrations of αR4 or αR5 as described in “Triton extraction of erythrocyte ghosts.” Proteins retained in the Triton shells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Lu and anti-GPC. Note the progressive decrease of Lu in αR4-resealed ghosts (A) but not αR5-resealed ghosts (B). GPC was unchanged in αR4-resealed ghosts (C).

Effect of introduction of αR4 into red cell ghosts on cellular adhesion to laminin

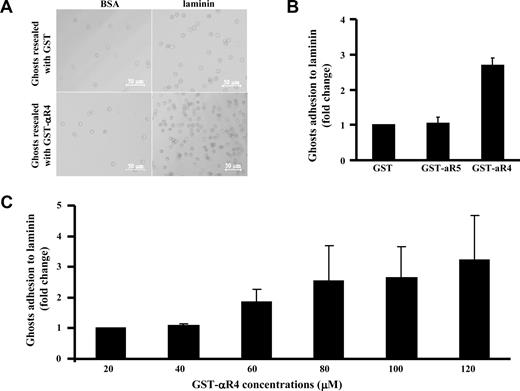

Taking advantage of our finding that the αR4 fragment can specifically disrupt the Lu-spectrin interaction in situ, we next examined the effect of the αR4 fragment on red cell adhesion to laminin. Adhesion of resealed ghosts containing GST or GST-αR4 fragment to BSA or laminin was assessed using a gravity-driven reverse suspension assay, as described in “Adhesion assay.” Figure 5A shows that few resealed ghosts containing GST or GST-αR4 fragment adhered to BSA-coated plates compared with laminin-coated plates, implying that the observed adhesion is mediated by Lu. Furthermore, incorporating GST-αR4 into red cells resulted in enhanced adhesion to laminin compared with incorporating GST or GST-αR5 (Figure 5B). Adhesion progressively enhanced with increasing concentrations of the αR4 fragment; and at the maximum concentration, enhancement was more that 3-fold (Figure 5C). These data clearly show that disruption of the Lu interaction with spectrin modulates its adhesive activity.

Effect of αR4 on adhesion of red cell ghosts to laminin. (A) Red cells resealed with 40 μM GST or GST-αR4 were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C on BSA- or laminin-coated 96-well microplates. Phase-contrast images show adherent cells after filling the wells with PBS and floating the microplate upside down for 40 minutes before microscopic observation. Cells were viewed with a Zeiss LSM META 510 Confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using a lens at 10×/0.30 EC Plan-Neofluar (Zeiss). Images were collected using the Zeiss Confocal microscope laser and the Laser Scanning microscope LSM 510 version 3.2 software (Zeiss). Images were cropped using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). (B) GST, GST-αR4, or GST-αR5 at 100 μM was introduced into red cells. Adhesion of the resealed cells to immobilized laminin was measured using the gravity-driven reverse suspension assay, described for panel A. Adhesion in the presence of GST was normalized as 1. Note the enhanced adhesion in the presence of αR4 fragment but not αR5 fragment; N = 3. (C) αR4 fragment at indicated concentrations was introduced into red cells. Adhesion was measured as described for panel B. Adhesion in the presence of 20 μM GST-α4 was normalized as 1, and the fold change was plotted against increasing concentrations of GST-α4. Note the progressively enhanced adhesion in the presence of increasing concentrations of αR4 fragment; N = 3.

Effect of αR4 on adhesion of red cell ghosts to laminin. (A) Red cells resealed with 40 μM GST or GST-αR4 were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C on BSA- or laminin-coated 96-well microplates. Phase-contrast images show adherent cells after filling the wells with PBS and floating the microplate upside down for 40 minutes before microscopic observation. Cells were viewed with a Zeiss LSM META 510 Confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using a lens at 10×/0.30 EC Plan-Neofluar (Zeiss). Images were collected using the Zeiss Confocal microscope laser and the Laser Scanning microscope LSM 510 version 3.2 software (Zeiss). Images were cropped using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). (B) GST, GST-αR4, or GST-αR5 at 100 μM was introduced into red cells. Adhesion of the resealed cells to immobilized laminin was measured using the gravity-driven reverse suspension assay, described for panel A. Adhesion in the presence of GST was normalized as 1. Note the enhanced adhesion in the presence of αR4 fragment but not αR5 fragment; N = 3. (C) αR4 fragment at indicated concentrations was introduced into red cells. Adhesion was measured as described for panel B. Adhesion in the presence of 20 μM GST-α4 was normalized as 1, and the fold change was plotted against increasing concentrations of GST-α4. Note the progressively enhanced adhesion in the presence of increasing concentrations of αR4 fragment; N = 3.

Discussion

Although the laminin-binding site in the extracellular domain of Lu has been identified, little was previously known about interactions of its cytoplasmic tail. In nonerythroid MDCK cells, Ubc9 protein (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 9) is a Lu-binding partner, regulating Lu/Lu(v13) stability at the membrane of these polarized epithelial cells.39 In red cells, it was discovered that Lu isoforms directly bind to spectrin.24 A major result of the current study is the identification of the Lu and Lu(v13) attachment site in spectrin. Using pull-down assays with spectrin fragments encompassing the entire α- and β-spectrin sequences, the binding site for Lu and Lu(v13) was identified as the αR4 repeat, which is contained within the 5 N-terminal repeats of α-spectrin. Independent confirmation of the specificity of this interaction was acquired by using a competitive inhibition assay showing that αR4 inhibited the binding of spectrin dimer to Lu or Lu(v13). Kinetic analysis of the spectrin-Lu linkage by a real-time plasmon resonance assay revealed that spectrin-Lu(v13)– and αR4-Lu(v13)–binding affinities were in the micromolar affinity range. To complement these in vitro studies, we tested the effect of disrupting the Lu-spectrin interaction on the cytoskeletal content of Lu in situ. We determined that the Lu content within the cytoskeletal fraction progressively decreased with increasing concentrations of αR4 in the presence of detergent, indicating that αR4 can specifically disrupt the Lu-spectrin interaction in situ, weakening the linkage of Lu to the cytoskeleton.

Spectrin repeats have been traditionally viewed as modules that are used to build long, elastic, extended molecules, and the mechanical properties of recombinant spectrin repeats have been extensively studied.33,34,40,41 In addition to their principal role as an elastic module, there is increasing evidence that spectrin repeats may also serve as docking sites for cytoskeletal and signal transduction proteins. For example, the repeats of α-actinin (a member of spectrin family) have been shown to interact with cytoplasmic domains of integrins42 and intercellular adhesion molecules.43,44 We have recently demonstrated that phosphatidylserine binds directly to clusters of spectrin repeats (α-spectrin repeats 8-10 and β-spectrin repeats 2-4 and 12-14).33,45 We also discovered that, in malaria-infected red cells, secreted parasite proteins bound to distinct spectrin repeats.37,46 These earlier findings, coupled with our current data, strongly suggest that spectrin as well as its family members serve as scaffolds for protein assembly.

In earlier studies, we discovered that Lu is a specific, high affinity receptor for the laminin α5 polypeptide chain, a constituent of laminins 10/11 (also termed laminins 511/52120 ).22 Several investigators have sought to identify the laminin ligand-binding site on the Lu extracellular domain.22,47 We determined that the 3 membrane distal IgSF domains were required for laminin attachment.22 More recently, we have reported that Asp312 of Lu and the surrounding group of negatively charged residues in the region of the linker between IgSF domains 2 and 3 form the laminin binding site. Small-angle X-ray scattering and X-ray crystallography have revealed that extracellular Lu is an extended structure with a distinctive bend between IgSF domains 2 and 3. This linker between the second and third domains appears flexible and is crucial for creating the Lu conformation required for laminin binding.23 Our current data now detail an important interaction of the Lu cytoplasmic tail linking it to the cytoskeleton.

Another major finding of the current study was that specifically disrupting the Lu-spectrin interaction by exogenously incorporated αR4 led to an increased adhesivity of resealed ghosts to laminin. The basis of the increased adhesion to the laminin matrix when Lu is released from the membrane cytoskeleton is uncertain, but a plausible mechanism requires the freely floating transmembrane Lu molecules to cluster and thereby generate a large adhesive force. This notion is supported by evidence in nonerythroid cells showing that clustering of membrane receptors enhances adhesion.48,49

Accumulating evidence strongly suggests that Lu-laminin α5 interactions contribute to the pathophysiology of several severe red cell diseases characterized by thrombosis and/or vaso-occlusion. It has been shown that red cells from patients with polycythemia vera demonstrate 3.7-fold increased adherence mediated by Lu-laminin α5 attachments compared with normal red cells.7 Moreover, Lu is constitutively phosphorylated in these abnormal erythrocytes, raising the intriguing question of whether the mechanism(s) activating Lu adhesion is mediated by phosphorylation. Sickle red blood cells also adhere to endothelial basement membrane via Lu-laminin α5 binding.3 Epinephrine increases Lu-laminin α5-mediated sickle red cell binding6 ; further, the Lu cytoplasmic tail is phosphorylated in epinephrine-stimulated sickle cells.50 However, the molecular basis for increased adhesion resulting from phosphorylation of the Lu cytoplasmic tail is not yet understood. Considered together with our present findings, we speculate that phosphorylation of the Lu cytoplasmic tail weakens its interaction with spectrin, enabling the freely floating transmembrane Lu molecules to cluster and thereby generate a large adhesive force. Future proof of such a mechanism could stimulate the design of novel therapeutics for polycythemia vera and sickle cell disease.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants DK56267, DK26263, DK32094, and HL31579), the National Health Service Research and Development Directorate (United Kingdom), and by the Director, Office of Health and Environment Research Division, US Department of Energy, under contract DE-AC03-76SF00098.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: X.A. and J.A.C. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; E.G., X.Z., and X.G. performed experiments and analyzed the data; and D.J.A. and N.M. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joel Anne Chasis, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Building 84, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720; e-mail: jachasis@lbl.gov.