Abstract

Proteolytic events at the cell surface are essential in the regulation of signal transduction pathways. During the past years, the family of type II transmembrane serine proteases (TTSPs) has acquired an increasing relevance because of their privileged localization at the cell surface, although our current understanding of the biologic function of most TTSPs is limited. Here we show that matriptase-2 (Tmprss6), a recently described member of the TTSP family, is an essential regulator of iron homeostasis. Thus, Tmprss6−/− mice display an overt phenotype of alopecia and a severe iron deficiency anemia. These hematologic alterations found in Tmprss6−/− mice are accompanied by a marked up-regulation of hepcidin, a negative regulator of iron export into plasma. Likewise, Tmprss6−/− mice have reduced ferroportin expression in the basolateral membrane of enterocytes and accumulate iron in these cells. Iron-dextran therapy rescues both alopecia and hematologic alterations of Tmprss6−/− mice, providing causal evidence that the anemic phenotype of these mutant mice results from the blockade of intestinal iron export into plasma after dietary absorption. On the basis of these findings, we conclude that matriptase-2 activity represents a novel and relevant step in hepcidin regulation and iron homeostasis.

Introduction

Pericellular proteolysis is an essential event that determines the relations between the cell and its microenvironment. This crucial process in the development and maintenance of multicellular organisms requires the remodeling of extracellular matrix components as well as the posttranslational regulation of a wide range of cell-surface receptors, regulatory proteins, and adhesion molecules.1 The increasing relevance of proteolytic processes localized at the cell surface has attracted notable attention on membrane-associated proteolytic systems, including the family of type II transmembrane serine proteases (TTSPs).2,3 The TTSP family is composed of more than 20 different members that share a number of structural features: a single-pass transmembrane domain located near the short cytoplasmic amino-terminal tail, a central region containing different protein-interacting domains, and a carboxy-terminal catalytic region with the structural characteristics of serine proteases. The large variability of the central modular region together with the diverse expression patterns of TTSP family members suggest that these enzymes may play different physiologic and pathologic roles, although only a few of these functions have been identified so far. Thus, enteropeptidase is mainly expressed in the duodenum and plays an essential role in food digestion as activator of pancreatic trypsinogen to trypsin.4 Hepsin, is mainly expressed in liver, but it is highly up-regulated in prostate cancer.5,6 Matriptase/MT-SP1 is a widely studied member of the TTSP family because of its relevance in diverse processes, including cancer progression.7,8 Mutant mice deficient in matriptase die shortly after birth because of aberrant skin development that compromises epidermal barrier function and causes mice dehydration.9 Corin is a TTSP family member mainly expressed in the heart and involved in the activation of proatrial natriuretic peptide, a cardiac hormone essential for the regulation of blood pressure.10 TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 are up-regulated or structurally altered in prostate cancer.11,12 Other members of this protease family whose physiologic and pathologic roles still remain unclear are spinesin/TMPRSS5,13 MSPL (mosaic serine protease large form),14 matriptase-3,15 polyserase-1,16 as well as the different components of the HAT (human airway trypsin-like protease)/DESC (differentially expressed in squamous cell carcinoma) subfamily.17,18

Matriptase-2 (TMPRSS6) is another TTSP family member of unknown function, but whose study has achieved particular interest because of its structural and enzymatic similarities with matriptase and to its putative role as a tumor suppressor enzyme in human breast cancer.19-21 This enzyme was first identified and cloned in our laboratory19 as part of our ongoing studies aimed at characterizing the human degradome, which is defined as the complete set of proteases produced by human cells.22,23 Matriptase-2 expression is mainly circumscribed to liver in both human and mouse, suggesting tissue-specific functions for this enzyme.19,24 Nevertheless, minor matriptase-2 expression has also been detected in kidney, uterus, and the nasal cavity.24 Matriptase-2 shares the structural organization of TTSPs, including the short cytoplasmic domain, a type II transmembrane sequence, a stem region with 2 CUB (complement factor C1s/C1r, urchin embryonic growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein) domains and 3 LDLR (low-density lipoprotein receptor) tandem repeats, and the carboxy-terminal serine protease domain.19,24 In addition, matriptase-2 contains a SEA (sea urchin sperm protein, enteropeptidase, agrin) domain that conserves a potential cleavage motif sequence that may release the enzyme from the cell surface, as reported for other TTSPs.20 Matriptase-2 can degrade in vitro extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin, fibrinogen, and type I collagen and to activate single-chain uPA although with low efficiency compared with matriptase.19 However, at present, little information is available about the in vivo functional relevance of matriptase-2 in both physiologic and pathologic processes. To further characterize the in vivo role of this type II transmembrane serine protease, we have generated mutant mice deficient in matriptase-2. In this work, and after a series of phenotypic and molecular analysis of Tmprss6−/− mice, we provide evidence that matriptase-2 is an essential regulator of iron homeostasis.

Methods

Tmprss6 gene targeting

A 3′-Hprt chromosomal engineering targeting vector was used to generate Tmprss6−/− mice following an insertional targeting strategy.25 A 7068-bp homology region, containing exons 3 to 6, was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from a murine genomic 129S7-derived PAC clone by using Long-Expand High Fidelity PCR mix (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and it was cloned into the AscI site of the 3′-Hprt vector (a kind gift of Dr A. Bradley, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, United Kingdom). The targeting vector was digested with EcoRI to remove an internal EcoRI fragment in the homology region and to create a “gap” that will be repaired during the targeting event. The targeting vector was linearized by digestion with EcoRI and electroporated into HM-1 embryonic stem cells. Resistant clones were selected with puromycin by using standard protocols. Homologous recombination was confirmed in the screened clones by Southern blot hybridization with the gap region which was used as a probe, after NdeI digestion. During the targeting event the gap is repaired and, as a consequence of the duplicated region generated, a novel 18-kb fragment is detected by the gap probe in addition to the 9-kb wild-type fragment. The heterozygous stem cells identified were aggregated to CD1 morulas and transferred into uteri of pseudopregnant females to generate chimeras. Chimeric males were mated with C57BL/6J females. A new strategy of genotyping was used to screen the offspring by using Southern blotting analysis of tail genomic DNA digested with SspI and hybridized with a 3′-external probe amplified from a genomic PAC. This probe was a 593-bp fragment amplified with primers 5′-GTCTCAGGTTCCCTGAGCCTG-3′ and 5′-GTGCCAAACACTCAGGG ATGC-3′.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated from frozen liver samples obtained from wild-type and mutant adult mice by using a commercial kit (RNeasy Mini Kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). A total 10 μg denatured RNA from liver was separated by electrophoresis on agarose gels and transferred to Hybond N+ (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Blots were hybridized with random primed 32P-labeled cDNA probes for mouse Tmprss6 and hepcidin. The cDNA probe for hepcidin was obtained by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using 1 μg total RNA from mouse liver and oligodT as primer, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After RT, 2 μL of the mixture were used for PCR with the following murine hepcidin-specific oligonucleotides: mHepcidinFw, 5′-CAGCAGAACAGAAGGCATGA; and mHepcidinRv, 5′-AGATGCAGATGGGGA AGTTG. The specific probe used to detect Tmprss6 was prepared from the murine Tmprss6 cDNA plasmid by digestion with BamHI. Blots were rehybridized with a beta-actin (Actb) cDNA probe as an indicator of RNA loading.

Transcriptional profiling and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated as described before. Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). In vitro transcription was carried out with the Bioarray high yield RNA transcript labeling kit (Enzo Diagnostics, New York, NY). The biotin-labeled cRNA was purified, fragmented, and hybridized to GeneChip Mouse 430 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). All microarray data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) of NCBI through accession number GSE11632.25 Real-time quantification of hepcidin transcript levels was performed by using Applied Biosystems Taqman gene expression assays in an ABI7000 Sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Hepcidin transcript abundance was calculated in triplicated relative to the expression of the stable housekeeping gene Actb. The average relative expression of hepcidin in wild-type mice was assigned an arbitrary value of 100 in each experiment.

Blood analysis and iron-dextran treatment

Mouse experimentation was done according to the guidelines of the University of Oviedo (Oviedo, Spain). Whole blood was collected retro-orbitally into heparinized-coated tubes. Plasma iron and unsaturated iron binding capacity (UIBC) were determined using a colorimetric method (Biolabo, Maizy, France). The total iron binding capacity (TIBC) was calculated as the sum of plasma iron and UIBC, and the percentage of transferrin saturation used the formula plasma iron/TIBC × 100. Peripheral blood smears were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for morphologic examination. Where indicated, 5 mg (8-week-old) or 2 mg (10-day-old) iron-dextran (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was injected subcutaneously weekly to knock-out mice.

Tissue iron staining and immunohistochemistry

Duodenal samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Deparaffined tissue sections were stained with Perls Prussian blue stain for nonheme iron, after nuclear red counterstaining by using standard procedures. To perform immunohistochemistry analysis, deparaffined and rehydrated sections were rinsed in PBS (pH 7.5). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a rabbit polyclonal antibody anti–mouse ferroportin (LifeSpan Biosciences, Seattle WA), diluted 1:100. Then sections were incubated with an anti–rabbit EnVision system–labeled polymer-HRP (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA) for 30 minutes, washed, and visualized with diaminobenzidine. Sections were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted in Entellan. Sections were examined using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope, and images were acquired with a Nikon DS-Si1 camera and Nikon NIS-Elements F2.20 software (Nikon, Melville, NY).

Statistical analysis

The mean values and the corresponding standard error of the means (SEMs) were calculated. Differences between mean values were analyzed by 2-tailed Student t test. A value of P less than .05 was considered significant. Statistically significant differences are shown with asterisks.

Results

Generation of mice deficient in matriptase-2

To analyze the in vivo role of matriptase-2, we designed an insertion vector for gene targeting, to provide a high targeting frequency26 (Figure 1A). According to this strategy, after electroporation into HM-1 embryonic stem cells (129/Ola background), the linearized and gapped vector would integrate into the target locus generating a duplication of the entire region of homology, including the repaired gap sequence (Figure 1B). By following this procedure, we finally identified several correctly targeted clones that were used to generate chimeras and finally heterozygous mice. After intercrossing heterozygous mice from the F1 generation, we obtained Tmprss6+/+, Tmprss6+/−, and Tmprss6−/− mice in the expected Mendelian ratios (Figure 1C). Northern blot analysis of total RNA from liver of wild-type and knock-out animals confirmed the complete absence of Tmprss6 transcript in Tmprss6−/− mice (Figure 1D). Tmprss6−/− mice exhibited slight signs of growth retardation that were more pronounced in female mice. Thus, we observed significant differences between the body weight of 4-week-old control and mutant female mice (control, 12.0 ± 0.4 g, n = 26, vs knockout, 10.2 ± 0.5 g, n = 15; P < .05). Likewise, we observed a marked retardation in ovarian maturation in adult Tmprss6−/− females that could be linked to the infertility observed in these mutant females.

Gene targeted disruption of the Tmprss6 gene. (A) Partial genomic structure of the murine Tmprss6 gene (top). Exon coding sequences are indicated as black bars. The targeting vector duplicates exons III to VI (bottom). E indicates EcoRI; S, SspI; N, NdeI; 3′Hprt, 3′-half Hprt minigene; Puro, puromycin resistance gene; Ag, K14 Agouti minigene. (B) Predicted structure of the targeted allele. (C) Southern blot analysis of DNA from Tmprss6+/+, Tmprss6+/−, and Tmprss6−/− mice digested with SspI. Hybridization with the 3′-external probe detects the expected 33-kb and 9-kb bands corresponding to wild-type and mutant alleles, respectively. (D) Northern blot analysis of liver tissues obtained from wild-type and Tmprss6−/− mice showing the absence of full-length Tmprss6 mRNA expression in mutant mice.

Gene targeted disruption of the Tmprss6 gene. (A) Partial genomic structure of the murine Tmprss6 gene (top). Exon coding sequences are indicated as black bars. The targeting vector duplicates exons III to VI (bottom). E indicates EcoRI; S, SspI; N, NdeI; 3′Hprt, 3′-half Hprt minigene; Puro, puromycin resistance gene; Ag, K14 Agouti minigene. (B) Predicted structure of the targeted allele. (C) Southern blot analysis of DNA from Tmprss6+/+, Tmprss6+/−, and Tmprss6−/− mice digested with SspI. Hybridization with the 3′-external probe detects the expected 33-kb and 9-kb bands corresponding to wild-type and mutant alleles, respectively. (D) Northern blot analysis of liver tissues obtained from wild-type and Tmprss6−/− mice showing the absence of full-length Tmprss6 mRNA expression in mutant mice.

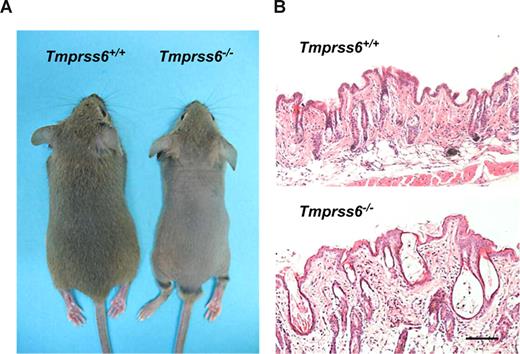

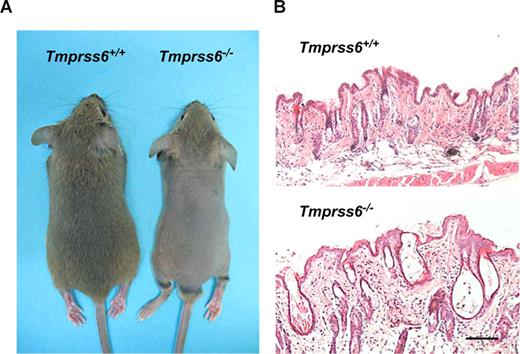

Tmprss6−/− mice exhibit a cyclic hair loss phenotype

Mice deficient in Tmprss6 display an overt phenotype of alopecia. Knockout pups started to show hair loss on the back at approximately 2 weeks of age, although the head of these mutant mice did not show any evidence of hair loss. By 4 weeks of age, Tmprss6−/− mice displayed a completely nude phenotype in the dorsal and ventral regions of the thorax and abdomen (Figure 2A). This alopecia condition lasted for approximately 10 days, and then new hair growth was initiated, as shown by the change in back skin color followed by a complete recovery of the hair. A few days later, a progressive hair loss began again, and a phenotype of diffuse alopecia in the dorsal region was definitively maintained during adult life. Histologic analysis showed that skin from 4-week-old mice had a reduced number of pillar units and the hair follicles were disorganized, dystrophic, and hypoplastic, showing a thinner outer root sheath at the isthmus and inferior segment level. Likewise, mutant mice displayed a pronounced infundibular ectasia with hyperkeratosis (Figure 2B). In adult Tmprss6−/− mice, the reduced number of pillar units as well as the hypoplastic phenotype were also observed in the skin. However, the hyperkeratosis and ectasia almost disappeared (data not shown).

Alopecia phenotype in Tmprss6−/− mice. (A) Representative photographs of 4-week-old Tmprss6+/+ and Tmprss6−/− littermate mice. (B) Skin sections from 4-week-old wild-type and Tmprss6−/− mice showing dystrophic hair follicles and hyperkeratosis in Tmprss6-null tissue, compared with the wild-type. Bar represents 100 μm; magnification, 20×/0.40 NA.

Alopecia phenotype in Tmprss6−/− mice. (A) Representative photographs of 4-week-old Tmprss6+/+ and Tmprss6−/− littermate mice. (B) Skin sections from 4-week-old wild-type and Tmprss6−/− mice showing dystrophic hair follicles and hyperkeratosis in Tmprss6-null tissue, compared with the wild-type. Bar represents 100 μm; magnification, 20×/0.40 NA.

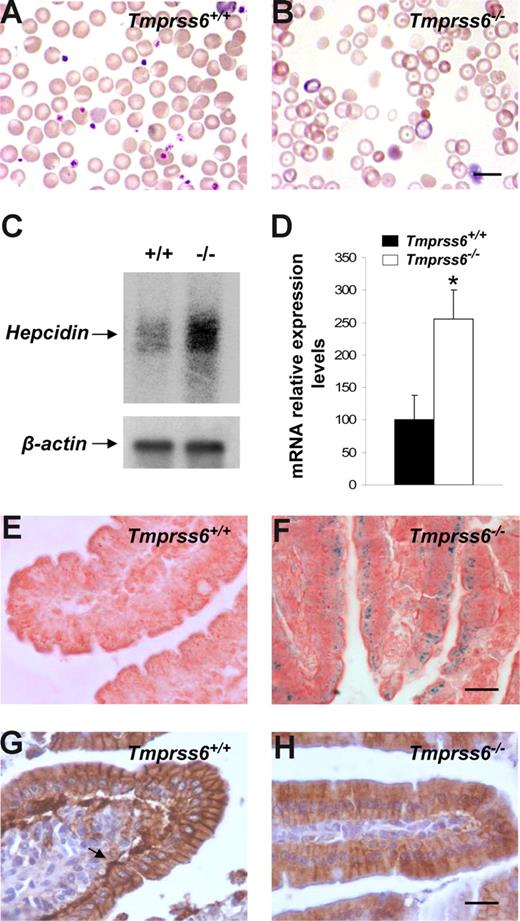

Hepcidin up-regulation causes severe anemia in Tmprss6−/− mice

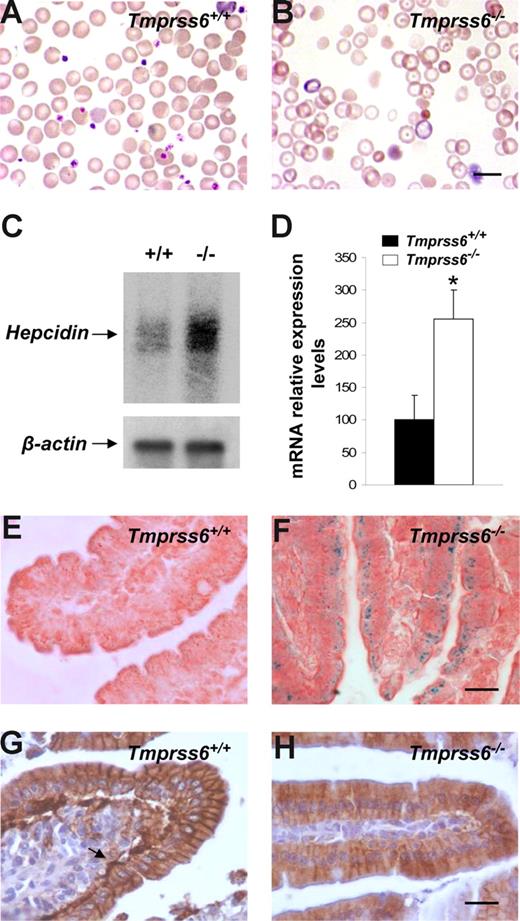

The phenotypic features of hair loss present in Tmprss6−/− mice, together with the observation of an evident pallor phenotype in newborn mice and the occurrence of several signs of growth retardation and female infertility, prompted us to analyze a series of hematologic variables in blood samples of these mutant mice. Plasma analysis showed that Tmprss6−/− mice were anemic and displayed both a severe iron deficiency and reduced transferrin saturation (Table 1). Likewise, Wright-Giemsa–stained blood smears from Tmprss6−/− mice showed a severe hypochromia and a slight phenotype of anisocytosis and poikilocytosis in comparison to wild-type counterparts (Figure 3A,B). These morphologic observations were confirmed after the quantification of several red blood cell variables (Table 2). Considering this anemic phenotype observed in Tmprss6−/− mice and the restricted expression pattern of this protease, which is mainly circumscribed to the liver, we hypothesized that the absence of matriptase-2 (Tmprss6) in this essential organ for iron homeostasis might alter certain regulatory factors involved in iron metabolism, alterations which could in turn contribute to explain the observed phenotype. To evaluate this possibility, we used oligonucleotide-based microarrays to analyze transcriptional changes in liver from Tmprss6−/− mice. Of 45 000 gene sequences present in the array, a total of 471 (1.05%) showed a higher than 2.5-fold decrease in expression levels in liver from Tmprss6−/− compared with control mice, whereas 221 genes (0.49%) were up-regulated more than 2-fold (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Analysis of these results showed that hepcidin, the principal hormonal regulator of systemic iron homeostasis, was clearly up-regulated in Tmprss6−/− mice compared with wild-type animals. Northern blot analysis and quantitative PCR of liver RNAs from different Tmprss6−/− mice confirmed that hepcidin was significantly up-regulated (2.5-fold increase) in mice deficient in this serine protease (Figure 3C,D). Additional studies showed that this hepcidin up-regulation was already present in Tmprss6−/− mice since birth. Thus, Tmprss6−/− newborn mice showed a 4.8-fold increase in expression levels of liver hepcidin in comparison to control mice (knockout, 485.7 ± 84.0, vs control, 100.0 ± 25.1; P < .01; n = 5 mice per genotype).

Hepcidin up-regulation reduces ferroportin expression and causes an anemic phenotype in Tmprss6−/− mice. Wright-Giemsa–stained blood smears from Tmprss6+/+ (A) and Tmprss6−/− (B) littermate mice. The figure shows the severe hypochromia found in mutant erythrocytes in comparison to wild-type ones. (C) Representative Northern blot analysis of liver tissues from wild-type and Tmprss6−/− mice showing the increased hepcidin mRNA expression in mutant mice. (D) TaqMan real-time PCR analysis of hepcidin expression in liver samples from 7-week-old Tmprss6+/+ and Tmprss6−/− mice. mRNA levels on the y-axis are expressed relative to β-actin levels. The average relative expression of hepcidin in wild-type mice was assigned an arbitrary value of 100. Values are means (± SEM). *P < .05; n = 5 mice per group. Perls Prussian blue stain for iron in sections of duodenal villi of 5-week-old Tmprss6+/+ (E) and Tmprss6−/− (F) mice shows iron accumulation in Tmprss6-null enterocytes. Representative immunostaining of ferroportin in duodenal tissue from 5-week-old Tmprss6+/+ (G) and Tmprss6−/− (H) mice. Arrow points to the basal expression of ferroportin in wild-type enterocytes, whereas positive basal staining is absent in Tmprss6-null cells. Bars represent 10 μm, magnification 100×/1.25 NA (A,B); bars 20 μm, magnification 60×/0.80 NA (E-H).

Hepcidin up-regulation reduces ferroportin expression and causes an anemic phenotype in Tmprss6−/− mice. Wright-Giemsa–stained blood smears from Tmprss6+/+ (A) and Tmprss6−/− (B) littermate mice. The figure shows the severe hypochromia found in mutant erythrocytes in comparison to wild-type ones. (C) Representative Northern blot analysis of liver tissues from wild-type and Tmprss6−/− mice showing the increased hepcidin mRNA expression in mutant mice. (D) TaqMan real-time PCR analysis of hepcidin expression in liver samples from 7-week-old Tmprss6+/+ and Tmprss6−/− mice. mRNA levels on the y-axis are expressed relative to β-actin levels. The average relative expression of hepcidin in wild-type mice was assigned an arbitrary value of 100. Values are means (± SEM). *P < .05; n = 5 mice per group. Perls Prussian blue stain for iron in sections of duodenal villi of 5-week-old Tmprss6+/+ (E) and Tmprss6−/− (F) mice shows iron accumulation in Tmprss6-null enterocytes. Representative immunostaining of ferroportin in duodenal tissue from 5-week-old Tmprss6+/+ (G) and Tmprss6−/− (H) mice. Arrow points to the basal expression of ferroportin in wild-type enterocytes, whereas positive basal staining is absent in Tmprss6-null cells. Bars represent 10 μm, magnification 100×/1.25 NA (A,B); bars 20 μm, magnification 60×/0.80 NA (E-H).

Because hepcidin is a negative regulator of iron export into plasma, we next explored the putative occurrence of iron deposits in the duodenum to evaluate whether the anemic phenotype of Tmprss6−/− mice could be due to a defective iron release into the circulation after diet absorption. Interestingly, Perls staining showed notable cellular iron retention in duodenal enterocytes of Tmprss6−/− mice (Figure 3E,F). Then, and considering that hepcidin blocks iron release through the down-regulation of ferroportin (the only known cellular iron exporter), we examined by immunohistochemistry the expression of this protein in the duodenum of wild-type and Tmprss6−/− mice. As shown in Figure 3G, a marked positive staining was observed in the basolateral membrane of duodenal enterocytes of wild-type mice. By contrast, ferroportin expression was almost absent in the basal membrane of Tmprss6−/− enterocytes (Figure 3H). Taken together, these results provide strong support to the hypothesis that the marked hepcidin up-regulation observed in Tmprss6−/− mice leads to the subsequent ferroportin removal of the enterocytes from these animals, impairing iron export into plasma and finally leading to iron deficiency anemia in Tmprss6−/− mice.

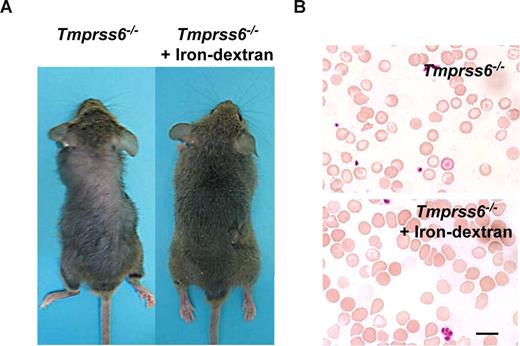

Iron therapy rescues alopecia and anemic phenotypes in Tmprss6−/− mice

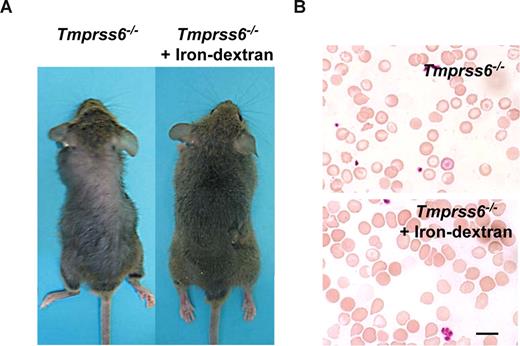

The above-mentioned findings showing that iron deficiency anemia in Tmprss6−/− mice was probably due to an impaired iron export into plasma, prompted us to consider the possibility of rescuing this phenotype by directly releasing iron into the circulatory system. Thus, Tmprss6−/− adult mice received weekly an iron-dextran subcutaneous injection for a period of 4 weeks, and the occurrence of putative changes in their alopecia and hematologic phenotypes was examined. As can be seen in Figure 4A, this iron-based therapy led to a complete recovery of hair in treated knock-out mice (Figure 4A). Likewise, this iron therapy rescued the hematologic deficiencies observed in Tmprss6−/− mice. Thus, blood smear examination showed a marked reduction of hypochromic red cells in treated Tmprss6−/− mice (Figure 4B). Finally, we evaluated whether the initial hair loss phenotype observed in young knockout mice was also iron dependent. To this purpose we used a group of 10-day-old Tmprss6−/− pups, which received weekly an iron-dextran subcutaneous injection for a period of 3 weeks. Consistent with the above-mentioned findings in adult mice, this treatment completely prevented hair loss in all treated young animals (n = 4; data not shown).

Iron-dextran therapy rescues the Tmprss6−/− phenotype. (A) Representative photograph of a 2-month-old Tmprss6−/− mice before (left) and after 1 month of iron-dextran treatment (right). (B) Wright-Giemsa–stained blood smears from untreated (top) and iron-dextran injected (bottom) Tmprss6−/− mice. Bar represents 10 μm; magnification, 100×/1.25 NA.

Iron-dextran therapy rescues the Tmprss6−/− phenotype. (A) Representative photograph of a 2-month-old Tmprss6−/− mice before (left) and after 1 month of iron-dextran treatment (right). (B) Wright-Giemsa–stained blood smears from untreated (top) and iron-dextran injected (bottom) Tmprss6−/− mice. Bar represents 10 μm; magnification, 100×/1.25 NA.

Discussion

A tightly regulated iron homeostasis is essential for life maintenance in eukaryotic organisms. Both iron deficiency and iron overload cause severe disorders in humans.27 Stable plasma concentrations and adequate levels of cellular iron are maintained through the strict control of a series of critical steps that regulate its absorption, transport, storage, and recycling. During the past years, the use of loss- and gain-of-function animal models together with genetic studies in patients with inherited iron homeostasis disorders have allowed the identification of key genes involved in iron metabolism.28,29 Most of these genes are iron transporters specific of different cell types. However, our unexpected findings derived from the phenotype analysis of Tmprss6−/− mice show for the first time that the lack of a proteolytic enzyme has severe consequences on iron balance under normal conditions. Thus, after generation and phenotype analysis of these mutant mice we first observed that Tmprss6 deficiency leads to severe iron deficiency anemia and hair loss. Further molecular analysis of tissues from the generated mutant mice showed that matriptase-2 is required for the maintenance of normal hepcidin expression levels as assessed by the finding that Tmprss6−/− mice showed significantly up-regulation in liver of the gene encoding this antimicrobial peptide. It is well established that hepcidin is a negative regulator of iron export, which is primarily secreted by hepatocytes and acts as a circulating hormone.30 Mice deficient in hepcidin and patients with mutations in this gene display a severe iron overload disorder.31,32 Conversely, transgenic mice overexpressing hepcidin in liver develop severe iron deficiency anemia.33 Furthermore, it was recently shown that hepcidin controls iron levels through the binding to ferroportin, the major iron exporter into the plasma. Thus, hepcidin binding results in ferroportin internalization from the cell surface with the subsequent degradation in lysosomes.34 It is also remarkable that conditional disruption of the ferroportin 1 gene causes iron deficiency anemia and iron accumulation in enterocytes.35 Consistent with the marked up-regulation of hepcidin, mice deficient in matriptase-2 show both a dramatic decrease in ferroportin levels at the basal membrane of duodenal cells and a marked increase in iron deposits in these enterocytes. Furthermore, the rescue of the hematologic phenotype after iron treatment of these mutant mice reinforces the hypothesis that the anemic phenotype observed in Tmprss6−/− mice results from the blockade of intestinal iron export into plasma after dietary absorption.

Upstream regulators responsible for the control of hepcidin expression have become the focus of attention in recent years because of their importance in the understanding of anemia and iron overload pathologies. According to our results, matriptase-2 is a novel candidate to act as in vivo regulator of hepcidin levels and function. Hepcidin is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level in response to a number of processes that affect iron balance, such as defective erythropoiesis, anemia, hypoxia, and inflammation.36,37 Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are the main positive regulators of hepcidin transcription under normal conditions.38 Binding of specific BMP ligands to BMP type I or type II receptors, located at the cell surface of hepatocytes, leads to an intracellular signaling cascade that results in phosphorylation of receptor Smads (Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8) that complex Smad4 to activate hepcidin transcription. Interestingly, it was recently described that hemojuvelin, a GPI-linked protein located at the cell surface of hepatocytes, acts as a BMP coreceptor promoting hepcidin transcription.38 However, soluble hemojuvelin released from the cell surface was shown to be a competitive antagonist of membrane-bound hemojuvelin, leading to a decrease in hepcidin transcription.39,40 In addition, it was reported that the in vitro shedding of BMP receptors reduces Smad signaling activation in primary human bone cells.41 These results suggest that proteolytic activity at the cell surface of hepatocytes might be considered as an important step in hepcidin regulation and iron balance. Nevertheless, further studies will be necessary to elucidate whether matriptase-2 is the protease responsible for these proteolytic events presumably occurring at the pericellular space.

In conclusion, our results provide the first causal evidence that the absence of a protease has severe consequences on iron homeostasis under normal conditions. These findings are in agreement with the recent results reported by Du et al42 that describe an ENU mouse mutant in Tmprss6 with a similar phenotype. Lack of matriptase-2 causes an iron deficiency anemia and a hair loss phenotype, characterized by hepcidin up-regulation and the blockade of intestinal iron export into plasma. On the basis of the results presented herein, we propose that matriptase-2–mediated functions constitute a novel step in hepcidin regulation. The recent finding that mutations in the human TMPRSS6 gene cause iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA)43 turns Tmprss6−/− mice into a useful genetic model for the analysis of molecular mechanisms that underlie human hematologic disorders whose molecular basis is yet unclear.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs F. V. Alvarez, I. Santamaría, A. Gutiérrez-Fernández, J. M. Freije, and A. Fueyo for helpful comments and advice; Dr D. W. Melton (Sir Alastair Currie Cancer Research UK Laboratories, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) for providing mouse embryonic stem cells; and M. Fernández, S. Alvarez, and M. S. Pitiot for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from FIS-Instituto Carlos III, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Fundación Lilly, Fundación “M. Botín” and the European Union (FP7). The Instituto Universitario de Oncología is supported by Obra Social Cajastur-Asturias, Spain.

Authorship

Contribution: G.V. and C.L-O. designed the experimental work; A.R.F., F.M.L., A.M.P., C.G., F.R., A.A., T.B., and G.V. performed research; A.R.F., F.M.L., A.M.P., C.G., F.R., A.A., T.B., R.C., G.V., and C.L-O. analyzed data; and G.V., A.R.F. and C.L-O. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Carlos Lopez-Otin, Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Oviedo, 33006 Oviedo, Spain; e-mail: clo@uniovi.es.