In this issue of Blood, Flowers and colleagues present the results of an international study evaluating the use of ECP for the treatment of chronic GVHD.

To date, the largest published chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)/extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) study was a retrospective analysis by Couriel and colleagues from M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. They reviewed ECP in patients who had failed multiple lines of immunosuppression.1 In that report, 61% of 63 heavily treated patients had a response; however, the survival was only 53% at 1 year.

Flowers et al should be congratulated for completing this prospective, well-organized, and multi-institutional study. ECP is currently used extensively off-label for chronic GVHD without a well-defined or standard treatment schedule or clinical endpoints. The fact that 23 centers in 4 continents were able to come together for this trial is an achievement in and of itself.

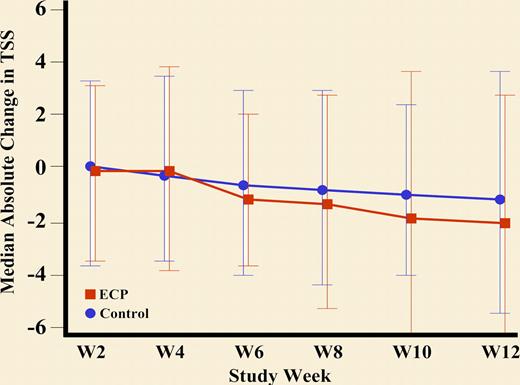

Briefly, patients with corticosteroid-dependent or refractory chronic GVHD were randomized to continue current therapy or add ECP. ECP was given 3 times per week the first week and then twice weekly until week 12. The primary end point was the median percentage change in the Total Skin Score (TSS) at 12 weeks compared with baseline (see figure). Very appropriately, the main outcome measures focused on cutaneous manifestations, as these are the most diagnostic and specific for chronic GVHD.

Improvement in TSS and reduction in steroid dose through week 12: Absolute median change in the Total Skin Score to Week 12. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2667.

Improvement in TSS and reduction in steroid dose through week 12: Absolute median change in the Total Skin Score to Week 12. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2667.

The first major strength of the study is that the TSS, a standardized measurement scale, was used. The TSS has been reported in one observational study by Greinix et al2 and requires further validation. Nevertheless, the fact that a scoring system like this one was used as opposed to subjective outcomes is a great achievement. There is currently an ongoing natural history study (personal communication with Dr Lee) to evaluate the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Criteria3 as well as other scales for grading chronic GVHD manifestations, such as the TSS. Until validation of these scales occurs, investigators should use the NIH Consensus Criteria for the purpose of standardization.

Second, the blinding of the observers in assessing a complex disease adds credibility to the results. Blinding the observers who measured the primary outcome was the next best alternative to blinding the actual therapy, which, as discussed by the authors, would have had major ethical implications, given the complexity of performing ECP. The importance of blinding the observers is made very clear by the huge difference between the main outcome measure (the median absolute change in TSS by the blinded observer) where there was no statistical improvement and a secondary outcome (investigator assessment of complete or partial response) where there was a large and statistically significant improvement in the ECP arm. This difference is most likely explained by investigator bias and not very well-defined criteria for a complete and partial response. A second explanation, though, could be that the TSS is not sensitive enough to change.

The study did not prove its primary end point. There was no statistical difference in median percent change from baseline in TSS when comparing ECP and control arms. It is possible that longer time is needed to achieve a response, especially in patients with sclerotic manifestations. However, the percentage of patients with sclerotic manifestations in this trial is not apparent. It is encouraging, though, that those patients who continued to week 24 had a decrease in TSS.

Some of the secondary endpoints are encouraging, such as being able to taper corticosteroids faster and more improvement in quality of life in the ECP arm. However, the corticosteroid taper was not mandated after 6 weeks, and therefore, it is possible that there was a bias to taper faster in the ECP arm simply because these patients were getting salvage therapy. Furthermore, improvement in quality of life could represent a placebo effect. A very important outcome is the impressive safety and tolerability of ECP and the fact that there was no increase in infectious complications in this arm. This may support the hypothesis that ECP is more immunoregulatory as opposed to immunosuppressive in its mechanism of action.

To summarize, Flowers et al report the results of the largest prospective and randomized study of ECP in corticosteroid refractory or dependent chronic GVHD. While the primary end point was not demonstrated, the study had numerous strengths, as described above. It remains to be seen whether either earlier institution or longer therapy with ECP improves the outcomes of patients with chronic GVHD.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■