Abstract

Acute HIV infection is characterized by massive loss of CD4 T cells from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Th17 cells are critical in the defense against microbes, particularly at mucosal surfaces. Here we analyzed Th17 cells in the blood, GI tract, and broncheoalveolar lavage of HIV-infected and uninfected humans, and SIV-infected and uninfected sooty mangabeys. We found that (1) human Th17 cells are specific for extracellular bacterial and fungal antigens, but not common viral antigens; (2) Th17 cells are infected by HIV in vivo, but not preferentially so; (3) CD4 T cells in blood of HIV-infected patients are skewed away from a Th17 phenotype toward a Th1 phenotype with cellular maturation; (4) there is significant loss of Th17 cells in the GI tract of HIV-infected patients; (5) Th17 cells are not preferentially lost from the broncheoalveolar lavage of HIV-infected patients; and (6) SIV-infected sooty mangabeys maintain healthy frequencies of Th17 cells in the blood and GI tract. These observations further elucidate the immunodeficiency of HIV disease and may provide a mechanistic basis for the mucosal barrier breakdown that characterizes HIV infection. Finally, these data may help account for the nonprogressive nature of nonpathogenic SIV infection in sooty mangabeys.

Introduction

The classic paradigm for CD4 T-cell differentiation delineates a pathway in which memory CD4 T cells are defined based on their ability to produce either interferon (IFN)–γ (Th1 cells) or interleukin (IL)–4 (Th2 cells).1 However, the exclusivity of this model has been challenged with the recent description of a CD4 T-cell subset (Th17 cells) that produces IL-17 and IL-22, but neither IFN-γ nor IL-4, in response to stimulation through the T-cell receptor.2-6 IL-17 and IL-22 function in vivo to promote recruitment of neutrophils to areas of bacterial infection, to induce proliferation of enterocytes and production of antibacterial defensins.7-9 Hence, Th17 cells likely play an important role in antibacterial immunity.10,11 In addition, IL-17 has been shown to play a central role in mouse models of autoimmunity.3,12-14 Although the majority of data regarding Th17 cells are derived from experiments in mice, recent studies have shown that Th17 cells can be identified in the blood of humans and characterized phenotypically based on expression patterns of certain chemokine and cytokine receptors, and appear to have specificity for bacterial and fungal antigens.15-17

Studies have recently shown that in HIV and pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection microbial products translocate from the lumen of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is both structurally and immunologically damaged during acute phase of infection, into the systemic circulation; these microbial products are bioactive in vivo and contribute to immune activation during the chronic phase of infection.18-22 However, naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys (SM) that do not progress to AIDS or manifest chronic immune activation do not develop microbial translocation.19 Because Th17 cells are thought to play a central role in antibacterial immunity, particularly at mucosal surfaces, we sought to examine the frequency, phenotype, functionality, antigen specificity, and in vivo infection frequency of Th17 cells in the peripheral blood (PB), GI tract, and broncheoalveolar lavage of HIV-infected and uninfected persons and SIV-infected and uninfected SMs.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-two HIV-infected antiretroviral therapy-naive, 4 antiretroviral-treated, and 38 HIV-uninfected healthy subjects were recruited for this study. Clinical details are shown in Table 1. HIV+ patients were classified as being “early” based on HIV seropositivity for less than 4 months with maintained CD4 T-cell counts of greater than 200 CD4 T cells/μL, “chronic” based on seropositivity for more than 1 year with CD4 counts greater than 200 CD4 T cells/μL, and “AIDS” based on a CD4 count of less than 200 CD4 T cells/μL. Viral load was determined using either the Roche Amplicor Monitor assay or the Roche Ultradirect assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). All subjects gave informed consent in compliance with the appropriate institutional review board procedures, and this study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Twelve naturally SIV-infected and 10 uninfected SMs were included in this cross-sectional analysis. All SMs were housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and maintained in accordance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. This study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee. In uninfected animals, negative plasma SIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and negative HIV-2 serology confirmed the absence of SIV infection.

Samples

PB mononuclear cells were prepared from venous blood by density gradient centrifugation. Intestinal mucosa was acquired by endoscopy and biopsy of the terminal ileum. Patients received standard colonoscopy preparation (GoLYTELY; Braintree Laboratories, Braintree, MA) and were sedated with Versed and fentanyl. A colonoscope was passed through the large intestine and the ileo-cecal valve. At least 8 to 10 biopsy samples were obtained with cold forceps using standard techniques. Biopsies were placed in RPMI media supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (R10) and shipped on wet ice overnight for T-cell analysis. GI tract samples were then dissected into 100-μL fragments and digested in Isocove media supplemented with 2 mg/mL of type II collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and 1 unit/mL of DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After digestion, samples were passed through a 100-μm filter and washed twice with R10. From this procedure, approximately 3 × 106 live lymphocytes are routinely isolated. Broncheoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells were obtained after anesthetizing the upper airways with 4% lidocaine nebulizer, and the vocal cords and proximal airways with 1% lidocaine solution. Bronchoscopy with lavage was performed through a fiberoptic bronchoscope wedged in a subsegmental bronchus of the right middle and right lower lobes as previously described.23 A volume of 150 mL normal saline at room temperature was instilled in 50-mL aliquots into the medial segment of the right middle lobe and repeated in the anterior segment of the right lower lobe. Subjects were sedated with stadol and midazolam. Typically, 300 mL was instilled to obtain a return of 125 to 200 mL BAL fluid. BAL fluid was filtered through 100-μm Nylon mesh (Tetko, Elmsford, NY) to remove debris, and was centrifuged at 400g for 10 minutes.

Rectal biopsies in sooty mangabeys

Current guidelines for experiments with SMs, being a protected species, allowed us to sample rectal biopsies. Fecal material was removed from the rectum, and a rectal scope/sigmoidoscope was then placed into the rectum. Rectal biopsies were obtained with biopsy forceps and placed in RPMI media supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (R10) and shipped on wet ice overnight for T-cell analysis. To separate intraepithelial lymphocytes from lamina propria lymphocytes, Hanks balanced salt solution containing 5 nM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution was added to the mucosal tissue and incubated with gentle shaking for 1 hour. The supernatant, which contains intraepithelial lymphocytes, was then collected, whereas the remaining tissue was digested in RPMI media supplemented with 0.75 mg/mL of collagenese for 2 hours at 37°C to obtain lamina propria lymphocytes. After digestion, samples were passed through a 70-μm filter to remove residual tissue fragments.

Flow cytometric analysis

Eighteen-parameter flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACSAria or LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin (PE), Cy7PE, Cy5.5PE, allophycocyanin (APC), Cy7APC, Texas Red PE, violet amine reactive dye, and Quantum-dot 705 were used as the fluorophores. At least 300 000 live lymphocytes were collected for all experiments. The list-mode data files were analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Functional capacity was determined after Boolean gating, and subsequent analysis was performed using Simplified Presentation of Incredibly Complex Evaluations (SPICE, version 2.9; Mario Roederer, Vaccine Research Center (VRC), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID], NIH). All values used for analyzing proportionate representation of responses were background-subtracted.

Intracellular cytokine assay

Stimulation was performed on fresh or frozen lymphocytes as described elsewhere.24 Freshly isolated or freshly thawed lymphocytes were resuspended at 106/mL in R10 supplemented with 1 μg/mL anti-CD28 and anti-CD49d antibodies. Anti-CD3 clone 12F6 was used to stimulate T cells mitogenically through the T-cell receptor at 10 pg/mL. In some cases, phorbol myristyl acetate (PMA), 5 ng/mL, and ionomycin, 1 μM (Sigma-Aldrich) were used to stimulate T cells mitogenically for comparative purposes. Peptides used to stimulate HIV-specific T cells were 15 amino acids in length, overlapping by 11 amino acids and encompassed HIV-1 Gag, Pol, Nef, and Env proteins (corresponding to the sequence of HXBc2) and were used at 2 μg/mL. Streptokinase (SK; Varidase; Wyeth-Ayerst, Princeton, NJ), Candida albicans (CA; Greer, Lenoir, NC), tetanus toxoid (Colorado Serum, Denver, CO), influenza (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), Epstein-Barr virus (Virusys, Sykesville, MD), cytomegalovirus (Lonza Walkersville, Walkersville, MD), and heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus (SA; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) were used to stimulate antigen-specific T cells. All stimulations were preformed in the presence of brefeldin-A (1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 hours at 37°C. All cells were surface-stained for phenotypic markers of interest and stained after fixation/permeabilization for cytokines (intracellular cytokine staining, ICS).

Monoclonal antibodies and T-cell phenotyping

Monoclonal antibodies and dead cell dye used for phenotypic and functional characterization of T-cell subsets were anti-CD3 Cy7APC, anti-CD8 Quantum-dot 705, anti–IFN-γ fluorescein isothiocyanate, anti-TNF Cy7PE, anti–IL-2 APC, anti-CCR5 APC, anti-CD95 Cy5PE (BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA), anti-CD45RO Texas Red PE, anti–IL-23R biotin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti-CD27 Cy5PE, anti-CD28 ECD (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA), anti–IL-17 PE (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), violet-fluorescent reactive dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and anti-CD4 Cy5.5PE (Invitrogen). Cells were initially gated based on characteristic light scatter properties, followed by positive staining for CD3 without binding to the dead cell dye, and then for CD4 staining without CD8 staining. Memory CD4 T-cell subsets were gated based on characteristic expression patterns of CD45RO and CD27 (or CD28 and CD95 for studies with SMs). As naive T cells produce neither IL-17 nor IFN-γ, and as antigen-specific T cells are not detectable in the naive T-cell pool, we report the frequency of cytokine-secreting cells is expressed as percentages of memory T cells.

Quantitative PCR

Quantification of HIV gag DNA in sorted memory CD4 T cells was performed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) by the 5′ nuclease (TaqMan) assay with an ABI7700 system (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA) as previously described.25,26 To quantify cell number in each reaction, qPCR was performed simultaneously for albumin gene copy number as previously described.27 Standards were constructed for absolute quantification of gag and albumin copy number.

Clonotypic analysis of TCR sequences

Antigen-specific CD4 T cells sorted based on production of intracellular IFN-γ or IL-17 after antigen-specific stimulation. Clonotypic analysis was performed as described previously using a DNA-based multiplex PCR.28

Results

Th17 cells are detected in PB

Initially, we sought to examine the functionality and phenotype of IL-17–producing CD4 T cells in the PB of humans. Using mitogenic anti-CD3 stimulation and polychromatic flow cytometry, we identified IL-17–producing CD4 T cells within both the CD27+ and CD27− memory CD4 T-cell compartments (Figure 1B). Naive CD4 T cells produced neither IFN-γ nor IL-17 (Figure 1B). Moreover, IL-17 production and IFN-γ production were generally mutually exclusive as only low frequencies of CD4 T cells produced both IFN-γ and IL-17. Finally, the IL-17– and IFN-γ–producing memory CD4 T cells were functionally heterogeneous as they could also produce TNF and/or IL-2 (Figure 1C).

Th17 cells are detected in PB and do not significantly overlap with Th1 CD4 T cells. PB lymphocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A. Cells were then stained and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” (A) Cells were gated based on characteristic light scatter properties, followed by positive staining for CD3 without binding to the dead cell dye, and then for CD4 staining without CD8 staining. Naive and memory CD4 T-cell subsets were gated based on characteristic expression patterns of CD45RO and CD27 (or CD28 and CD95 for studies with Sooty mangabeys, as shown in parentheses). (B) Individual subsets of CD4 T cells were analyzed for production of either IL-17 or IFN-γ. (C) The IL-17– and IFN-γ–producing memory subsets were further analyzed for the production of TNF and IL-2.

Th17 cells are detected in PB and do not significantly overlap with Th1 CD4 T cells. PB lymphocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A. Cells were then stained and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” (A) Cells were gated based on characteristic light scatter properties, followed by positive staining for CD3 without binding to the dead cell dye, and then for CD4 staining without CD8 staining. Naive and memory CD4 T-cell subsets were gated based on characteristic expression patterns of CD45RO and CD27 (or CD28 and CD95 for studies with Sooty mangabeys, as shown in parentheses). (B) Individual subsets of CD4 T cells were analyzed for production of either IL-17 or IFN-γ. (C) The IL-17– and IFN-γ–producing memory subsets were further analyzed for the production of TNF and IL-2.

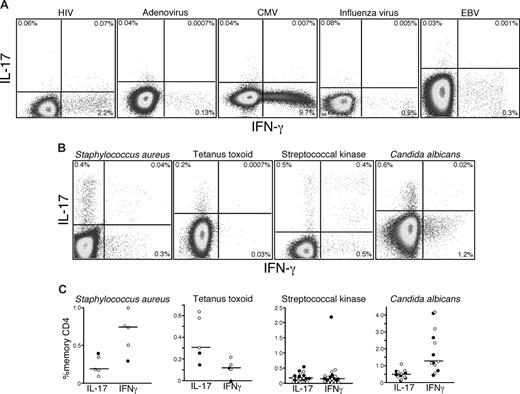

Antigen specificity of human Th17 cells

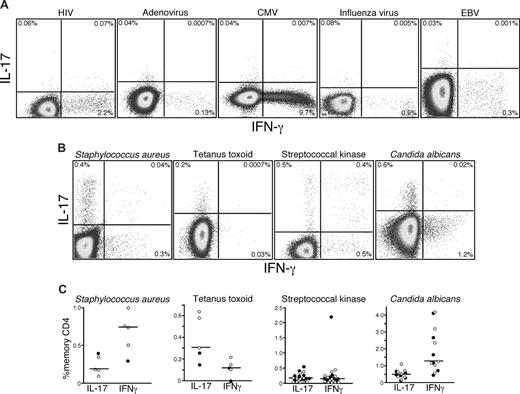

Given that Th17 cells can be detected after polyclonal stimulation in humans, we next sought to examine the antigen specificity of Th17 cells in vivo. Previous studies have detected Th17 cells in human PB that are specific for CA and Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens.15 These findings suggested that Th17 cells might play an important role in defense against pathogens that are normally encountered at mucosal surfaces. Hence, we examined Th17 responses to several antigens from viruses that are encountered at mucosal surfaces: HIV, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, influenza, and Epstein-Barr virus. Although we were able to detect CD4 T cells specific for each virus based on the production of IFN-γ, we consistently found no virus-specific CD4 T cells that produced IL-17 in any HIV-infected or uninfected person (Figure 2A). However, on stimulation with SK, heat-killed SA, tetanus toxoid, and CA, we detected IL-17 production by CD4 T cells from 13 of the patients we studied (Figure 2B,C), although not all patients in our cohort responded to each viral, bacterial, or fungal antigen. We also observed that, although some CD4 T cells produced IL-17 in response to SK, CA, and SA, others produced IFN-γ and found that these different cytokine-secreting populations, both responding to SK, contained different clones as defined by their TCRBV CDR3 region (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Taken together, these observations confirm the specificity of Th17 cells for bacterial and fungal antigens, show that they are phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous, and suggest that polarization to a Th1 or Th17 phenotype might not be dictated solely by the nature of the antigen.

Th17 cells respond to bacterial and fungal antigens. PB lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-infected and uninfected persons were stimulated with a variety of viral (A) or bacterial antigens (B) overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Production of IL-17 and IFN-γ by memory CD4 T cells in response to individual antigen-specific stimulation was measured by flow cytometry. (C) The frequencies of memory CD4 T cells from PB lymphocytes of several HIV+ (●) and HIV− patients (○) producing either IFN-γ or IL-17 in response to bacterial or fungal antigens are shown.

Th17 cells respond to bacterial and fungal antigens. PB lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-infected and uninfected persons were stimulated with a variety of viral (A) or bacterial antigens (B) overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Production of IL-17 and IFN-γ by memory CD4 T cells in response to individual antigen-specific stimulation was measured by flow cytometry. (C) The frequencies of memory CD4 T cells from PB lymphocytes of several HIV+ (●) and HIV− patients (○) producing either IFN-γ or IL-17 in response to bacterial or fungal antigens are shown.

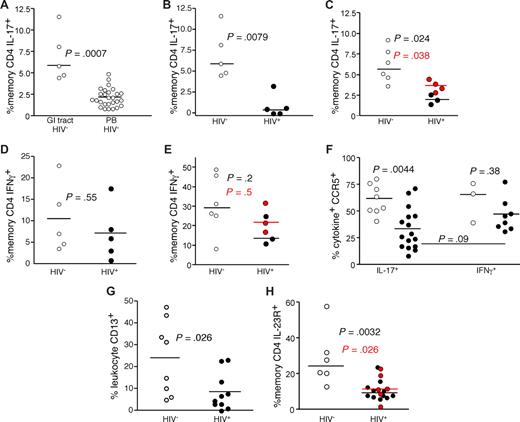

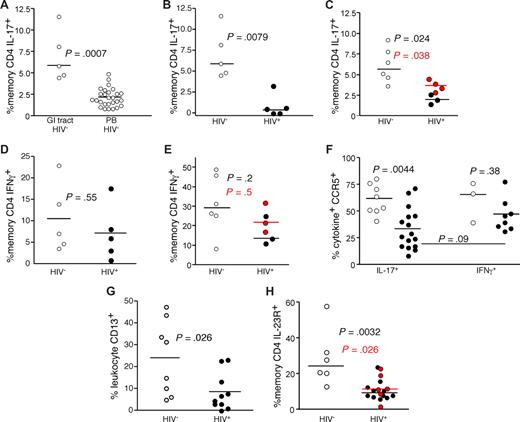

Preferential loss of Th17 CD4 T cells in the GI tract of HIV-infected patients

The finding that Th17 cells respond to bacterial antigens and are an important mediator of antibacterial defenses, coupled with previous data demonstrating a compromised GI structural29-31 and immunologic7,32-34 barrier in HIV-infected patients, led us to study the Th17 cell subset in the GI tracts of HIV-infected and uninfected persons (Figure 3). We found that anti-CD3 stimulation of GI tract T cells from HIV-uninfected persons revealed a significantly higher frequency of IL-17–producing CD4 T cells compared with PB (P < .001, Figure 3A). In stark contrast, we found significantly lower frequencies of IL-17–producing CD4 T cells in the GI tract of HIV-infected patients compared with uninfected persons (P = .008, Figure 3B). This finding was confirmed in a second cohort of patients using biopsies combined from the terminal ileum, colon, and rectum after mitogenic stimulation with PMA and ionomycin (P = .02, Figure 3C). Moreover, in 2 HIV-infected and 2 HIV-uninfected persons, we found no differences between Th17 cell frequencies between biopsies taken from the large and small bowel (data not shown), and recent studies in SIV-infected rhesus macaque found similarly low frequencies of Th17 cells in large and small bowel.21 Notably, Th17 cells remained at low frequency, even in the 4 patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. However, we found no significant difference between the frequencies of IFN-γ–producing GI CD4 T cells from HIV-infected and uninfected persons regardless of which biopsy site or stimulation method was used (Figure 3D,E). Hence, even though CD4 T cells are massively depleted from the GI tract of HIV-infected patients,32-34 the IL-17–producing CD4 T cells appeared to be preferentially affected. Moreover, although there may be differences regarding the degree of overall CD4 T-cell depletion across the GI tract,32-37 our data suggest that the preferential depletion of Th17 cells occurs throughout the entire GI tract in HIV-infected patients. Of note, we found that Th17 cells had the same proliferative capacity on mitogenic stimulation and were not more susceptible to activation-induced cell death compared with Th1 cells. We also found similar expression of BCL2 and Ki67 by Th1 and Th17 cells (data not shown). To determine whether the Th17 cells within the GI tract could be targets for HIV infection in vivo, we measured expression of CCR5 by Th1 and Th17 cells within in the GI tracts of HIV-infected and uninfected persons (Figure 3F). We found that the majority of both the GI tract Th1 and Th17 cells expressed CCR5 in uninfected persons. However, although the remaining Th1 cells in the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients maintained expression of CCR5, significantly fewer of the remaining Th17 cells expressed CCR5. Hence, there was a preferential loss of the CCR5+ Th17 targets for the virus, suggesting that the virus may play a direct role in their depletion. Moreover, we found a very slight trend toward a negative correlation between plasma viral load and the frequency of Th17 cells in the GI tract of HIV-infected patients (R = −0.5, P = .15, data not shown), and recent studies using large numbers of SIV-infected rhesus macaques found significant negative correlations between plasma levels of SIV and the frequencies of Th17 cells in both the small and large bowel.21 The numbers of Th17 cells in the GI tract were too low, however, to allow for their purification and measurement of infection frequency. An additional factor that could explain the preferential loss of Th17 cells compared with Th1 cells in the context of massive CD4 T-cell depletion overall is a change in the antigen-presenting milieu of the GI tract. Indeed, we found significantly lower frequencies of CD13+ myelomonocytic cells (comprising macrophages, dendritic cells, and granulocytes) within the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients compared with uninfected persons (Figure 3G). As our initial observations for the preferential loss of Th17 cells from the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients were based on functional capacity, this finding could be attributed to lack of functionality rather than the physical loss of Th17 cells per se. Therefore, we also measured the frequency of CD4 T cells in the GI tracts of HIV-infected and uninfected persons that expressed the IL-23 receptor, a surface protein expressed by Th17 cells.16 We found significantly lower frequencies of IL-23R+ memory CD4 T cells in the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients compared with HIV-uninfected persons (Figure 3H). Hence, phenotypic and functional analysis demonstrated preferential loss of Th17 cells from the GI tract in HIV infection.

Th17 cells are preferentially lost from the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients. (A) GI tract and PB lymphocytes from HIV-uninfected persons (○) were stimulated with anti-CD3 in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” GI tract lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-infected (●) and uninfected persons (○) were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight (B,D) or with PMA and ionomycin (C,E) for 4 hours in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in Figure 1. Frequencies of GI tract memory CD4 T cells that produce either IL-17 (A-C) or IFN-γ (D,E) were then measured by flow cytometry. In panels C and E, red symbols signify chronically HIV-infected patients on HAART. (F) Expression of CCR5 by GI tract Th1 and Th17 cells from HIV-infected (●) and HIV-uninfected (○) patients. (G) The frequency of CD13+ myelomonocytic cells within total GI tract leukocytes was assessed after gating for CD45 expression with exclusion of dead cells in cohorts of HIV-infected (●) and uninfected persons (○). (H) Expression of IL-23R by memory CD4 T cells in the GI tracts of HIV-infected (●) and HIV-uninfected persons (○).

Th17 cells are preferentially lost from the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients. (A) GI tract and PB lymphocytes from HIV-uninfected persons (○) were stimulated with anti-CD3 in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” GI tract lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-infected (●) and uninfected persons (○) were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight (B,D) or with PMA and ionomycin (C,E) for 4 hours in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in Figure 1. Frequencies of GI tract memory CD4 T cells that produce either IL-17 (A-C) or IFN-γ (D,E) were then measured by flow cytometry. In panels C and E, red symbols signify chronically HIV-infected patients on HAART. (F) Expression of CCR5 by GI tract Th1 and Th17 cells from HIV-infected (●) and HIV-uninfected (○) patients. (G) The frequency of CD13+ myelomonocytic cells within total GI tract leukocytes was assessed after gating for CD45 expression with exclusion of dead cells in cohorts of HIV-infected (●) and uninfected persons (○). (H) Expression of IL-23R by memory CD4 T cells in the GI tracts of HIV-infected (●) and HIV-uninfected persons (○).

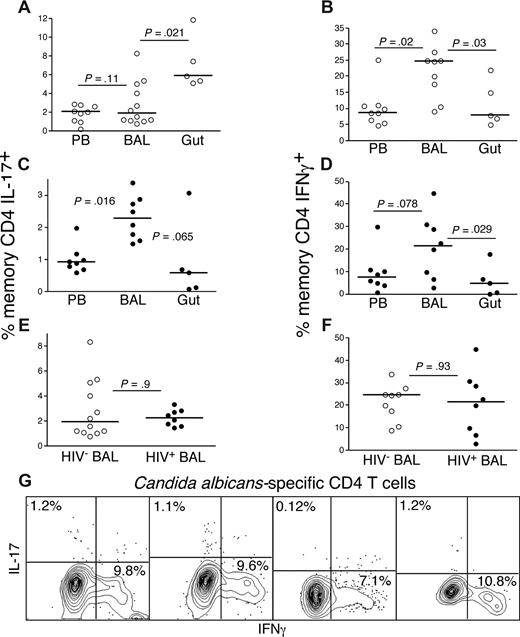

Maintenance of healthy frequencies of Th17 cells in BAL of HIV-infected patients

We have previously shown that, contrary to events in the HIV-infected GI tract, there appears to be a sparing of CD4 T cells from depletion in the BAL of HIV-infected patients.38 We therefore investigated whether the preferential loss of Th17 cells compared with Th1 cells from the GI tract was also reflected in BAL. Initially, we compared the frequencies of Th17 cells in blood, GI tract, and BAL of HIV-uninfected persons (Figure 4A) and found that the GI tract had significantly higher frequencies of Th17 cells compared with BAL (P = .021, Figure 4A). However, in HIV-infected patients, BAL had higher frequencies of Th17 cells compared with GI tract and PB (Figure 4C, P = .065). Moreover, BAL had higher frequencies of Th1 cells compared with PB or GI tract in HIV-infected and uninfected persons (Figure 4B,D). Thus, different mucosal sites appear to be affected differentially in HIV infection not only in terms of the quantity of CD4 T-cell depletion but also in terms of the functional qualities of the CD4 T-cell subsets therein as HIV-infected patients maintained healthy frequencies of Th1 and Th17 cells in BAL compared with HIV-uninfected persons (Figure 4E,F). Importantly, HIV-infected patients generally do not die of opportunistic infections during the asymptomatic chronic phase of the infection, and we found that some of the preserved Th17 cells in BAL responded to CA (Figure 4G).

Th17 cells are not preferentially lost from the BAL of HIV-infected patients. (A-F) GI tract, PB, and BAL lymphocytes from HIV-uninfected persons (○) and HIV-infected patients (●) were stimulated with anti-CD3 in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Frequencies of memory CD4 T cells that produce either IL-17 (A,C,E) or IFN-γ (B,D,F) were then measured by flow cytometry. (G) BAL lymphocytes from 4 HIV-infected patients were stimulated with CA antigen in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Production of either IL-17 or IFN-γ by memory CD4 T cells is shown.

Th17 cells are not preferentially lost from the BAL of HIV-infected patients. (A-F) GI tract, PB, and BAL lymphocytes from HIV-uninfected persons (○) and HIV-infected patients (●) were stimulated with anti-CD3 in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Frequencies of memory CD4 T cells that produce either IL-17 (A,C,E) or IFN-γ (B,D,F) were then measured by flow cytometry. (G) BAL lymphocytes from 4 HIV-infected patients were stimulated with CA antigen in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Production of either IL-17 or IFN-γ by memory CD4 T cells is shown.

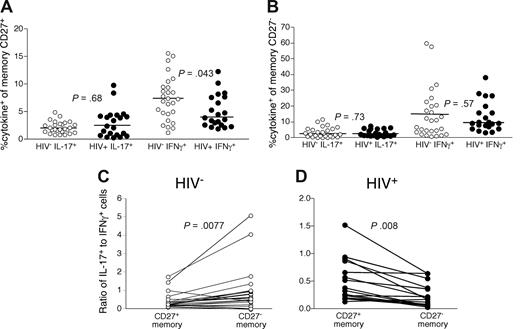

Th1 skewing on CD4 T-cell maturation in PB of HIV-infected patients

We next compared the frequency and phenotypes of IL-17–producing CD4 T cells in PB of HIV-infected and uninfected persons after anti-CD3 stimulation. We specifically examined the CD27+ and CD27− memory CD4 T cells as these memory subsets are maturationally distinct and the more mature, CD27−, subset has been shown to be expanded in HIV-infected patients.25,39,40 There is considerable phenotypic and functional overlap between the CCR7+“central memory” subset and CD27+ memory CD4 T cells and between the CCR7−“effector memory” subset and CD27− memory CD4 T cells. In doing so, we found no significant differences in the overall frequency of IL-17-producing CD4 T cells within either the CD27+ (Figure 5A) or CD27− (Figure 5B) memory T-cell subsets in HIV-infected patients compared with uninfected persons, indicating that their preferential loss is particular to the GI tract.

CD4 T cells in PB of HIV-infected patients are skewed toward a Th1 phenotype. PB lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-infected (●) and uninfected persons (○) were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in Figure 1. The frequency of memory CD27+ (A) and CD27− (B) CD4 T cells that produced IL-17 or IFN-γ was then measured by flow cytometry. The ratio of IL-17–producing cells to IFN-γ–producing cells was then compared within both memory CD27− and CD27+ CD4 T-cell subsets from HIV− (C, ○) and HIV+ (D, ○) patients. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

CD4 T cells in PB of HIV-infected patients are skewed toward a Th1 phenotype. PB lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-infected (●) and uninfected persons (○) were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in Figure 1. The frequency of memory CD27+ (A) and CD27− (B) CD4 T cells that produced IL-17 or IFN-γ was then measured by flow cytometry. The ratio of IL-17–producing cells to IFN-γ–producing cells was then compared within both memory CD27− and CD27+ CD4 T-cell subsets from HIV− (C, ○) and HIV+ (D, ○) patients. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

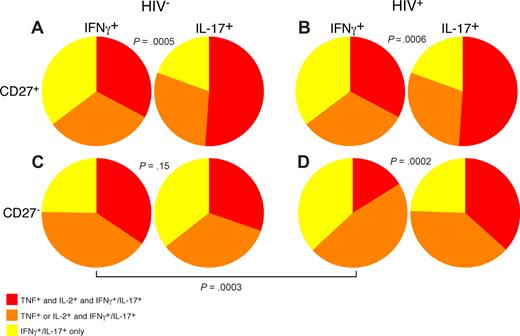

However, analysis of the relative frequencies of Th17 cells compared with Th1 cells among individual memory CD4 T-cell compartments revealed differences between HIV-infected and uninfected persons (Figure 5C,D). In HIV-uninfected persons, we observed significantly higher frequencies of Th17 cells compared with Th1 cells in the CD27− memory CD4 T-cell subset compared with the CD27+ memory CD4 T-cell subset (P = .008, Figure 5C). In contrast, CD27+ memory CD4 T cells in HIV-infected patients were more significantly likely to produce IL-17 compared with CD27− memory CD4 T cells (P = .008, Figure 5D). Thus, PB CD4 T cells from HIV-infected patients were skewed toward Th1 differentiation with maturation toward a CD27− memory phenotype. Together, these data for PB and the GI tract could suggest that either the proinflammatory state of the immune system in HIV-infected patients leads specifically to a Th1 phenotype or that Th17 cells are preferential targets for the virus in vivo.

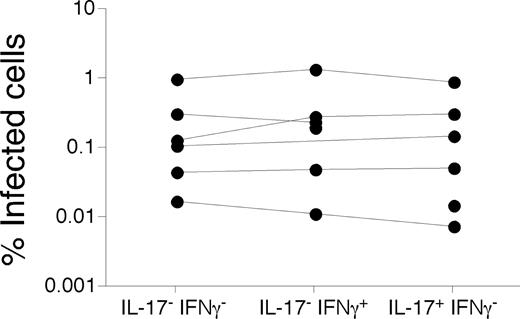

Th17 CD4 T cells are not preferentially infected by HIV in vivo in PB

Thus, to determine whether Th17 cells were preferentially infected by the virus in vivo, we stimulated PB cells with anti-CD3 and sorted CD27+ memory CD4 T cells that produced IL-17, IFN-γ, or neither by flow cytometry. Their infection frequency was then determined by qPCR for viral DNA (Figure 6). We specifically sorted functionally distinct CD4 T cells from only the CD27+ memory subset because phenotypic maturation is itself associated with lower frequencies of infected cells in vivo.25,41 Hence, any differences between infection frequencies could be directly attributed to functionality rather than maturational phenotype. We found no significant differences between the infection frequencies of any individual subset of CD27+ memory CD4 T cells based on production of IFN-γ or IL-17. Thus, although Th17 cells are capable of being infected by HIV in vivo and our data suggest that the virus may play a direct role in their depletion in the GI tract, Th17 cells in PB do not appear to be preferentially infected.

Infection frequencies of Th17 cells in PB. PB lymphocytes from a cohort of HIV-infected patients were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” CD27+ memory CD4 T cells that produced IFN-γ, IL-17, or neither were then sorted by flow cytometry, and the infection frequency was determined by quantitative PCR for viral DNA as described in “Quantitative PCR.”

Infection frequencies of Th17 cells in PB. PB lymphocytes from a cohort of HIV-infected patients were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” CD27+ memory CD4 T cells that produced IFN-γ, IL-17, or neither were then sorted by flow cytometry, and the infection frequency was determined by quantitative PCR for viral DNA as described in “Quantitative PCR.”

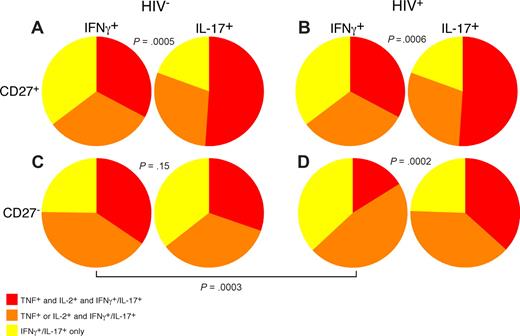

Th17 cells maintain polyfunctionality with maturation

Use of polychromatic flow cytometry allowed us to examine the overall functionality of PB Th1 and Th17 CD4 T cells in HIV-infected and uninfected persons by simultaneous measurement of IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 (Figure 7). In doing so, we found that, among both HIV-uninfected (21 patients) and infected patients (17 patients), CD27+ memory CD4 T cells that produce IL-17 were significantly more polyfunctional than IFN-γ–producing CD27+ memory CD4 T cells (Figure 7A,B). However, within the CD27− memory CD4 T-cell subset of HIV-uninfected persons, functionality of IL-17– and IFN-γ–producing CD4 T cells was similar (Figure 7C). Analysis of the CD27− memory CD4 T-cell subset from HIV-infected patients revealed that, unlike the same memory subset within HIV-uninfected persons, the IFN-γ–producing CD4 T cells were significantly less polyfunctional than the IL-17–producing subset. Our data thus show a specific functional deficit in circulating Th1 but not Th17 cells in HIV-infected patients; this phenomenon may contribute to the overall state of immunodeficiency. Indeed, recent data have suggested that decreased functionality of HIV-specific T cells is associated with progressive HIV disease.42

Th1 CD4 T cells are less functional than Th17 CD4 T cells in HIV-infected patients. PB lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-uninfected and -infected patients were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” The ability of IL-17–producing or IFN-γ–producing CD27+ (A,B) and CD27− (C,D) memory CD4 T cells to coproduce IL-2 and TNF was analyzed using SPICE as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

Th1 CD4 T cells are less functional than Th17 CD4 T cells in HIV-infected patients. PB lymphocytes from cohorts of HIV-uninfected and -infected patients were stimulated with anti-CD3 overnight in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” The ability of IL-17–producing or IFN-γ–producing CD27+ (A,B) and CD27− (C,D) memory CD4 T cells to coproduce IL-2 and TNF was analyzed using SPICE as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

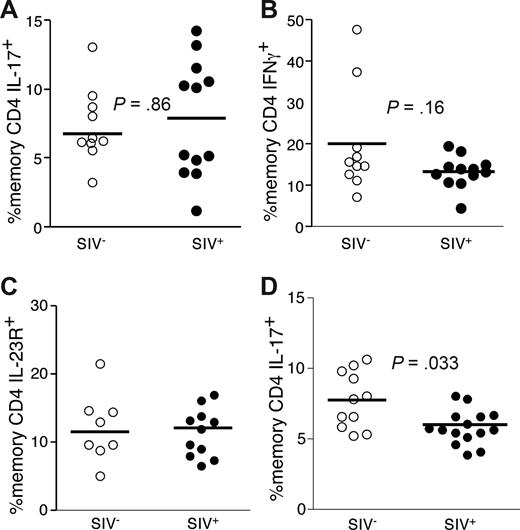

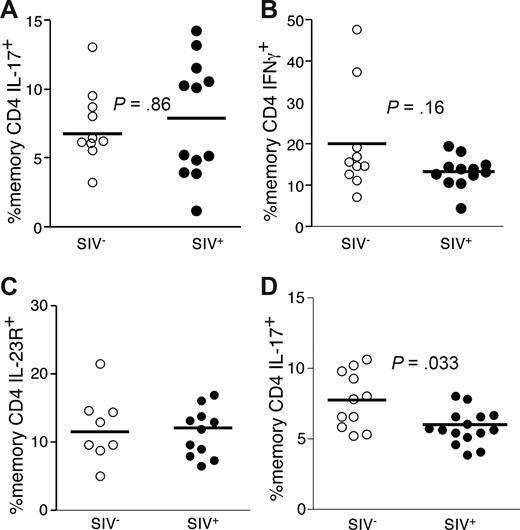

Th17 cells are maintained at healthy frequencies in the GI tract in nonpathogenic infection of SMs

SIV-infected SMs do not develop chronic immune activation or progress to AIDS43 and do not manifest microbial translocation.19 However, such nonpathogenic SIV infection nevertheless results in overall GI tract CD4 T-cell depletion during acute infection to levels that are 5% to 20% those of uninfected animals.44 Thus, we determined whether the finding of decreased Th17 cells is a feature particular to progressive, pathogenic lentiviral infection. Initially, we examined expression patterns of IL-17, IL-2, TNF, and IFN-γ by PB CD4 T cells from SMs and found the Th17 cells in SMs, as in humans, were functionally heterogeneous and were virtually mutually exclusive with Th1 cells (data not shown). We then studied Th1 and Th17 cells in the GI tracts of SMs and found that SIV-infected SMs maintained frequencies of functional GI tract Th17 and Th1 cells comparable with uninfected SMs (Figure 8A,B). In addition, we found similar frequencies of Th17 cell defined phenopytically (based on coexpression of CD4 and IL-23R) in the GI tracts of SIV-infected and uninfected SMs (Figure 8C). In PB, SIV-infected SMs had lower frequencies of Th17 cells compared with uninfected SMs (P = .038, Figure 8D). Thus in a nonpathogenic lentiviral infection, even in the context of overall CD4 T-cell depletion, Th17 cells are not preferentially lost from the GI tract.

Th17 cells are not preferentially lost from the GI tracts of SIV-infected SMs. GI tract lymphocytes from cohorts of SIV-infected (●) and uninfected sooty mangabeys (○) were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hours in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Frequencies of GI tract memory CD4 T cells that produce either IL-17 (A) or IFN-γ (B) were then measured by flow cytometry. (C) Expression of IL-23R by memory CD4 T cells in the GI tracts of SIV-infected (●) and SIV-uninfected sooty mangabeys (○). (D) Frequencies of PB memory T cells that produce IL-17 from SIV-infected (●) and uninfected (○) sooty mangabeys.

Th17 cells are not preferentially lost from the GI tracts of SIV-infected SMs. GI tract lymphocytes from cohorts of SIV-infected (●) and uninfected sooty mangabeys (○) were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hours in the presence of brefeldin A and stained as in “Intracellular cytokine assay.” Frequencies of GI tract memory CD4 T cells that produce either IL-17 (A) or IFN-γ (B) were then measured by flow cytometry. (C) Expression of IL-23R by memory CD4 T cells in the GI tracts of SIV-infected (●) and SIV-uninfected sooty mangabeys (○). (D) Frequencies of PB memory T cells that produce IL-17 from SIV-infected (●) and uninfected (○) sooty mangabeys.

Discussion

We examined the frequency, phenotype, functionality, and anatomic distribution of Th17 cells in HIV-infected and uninfected humans and in SIV-infected and uninfected SMs monkeys. The principle findings were as follows: (1) the GI tract is enriched in Th17 cells compared with PB in healthy patients; (2) CD4 T cells in blood of HIV-infected patients are skewed away from a Th17 phenotype toward a monofunctional Th1 phenotype with cellular maturation; (3) PB Th17 cells are infected by HIV in vivo, but not preferentially so compared with Th1 cells; (4) Th17 cells are preferentially diminished compared with Th1 cells in the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients; (5) Th17 cells are preserved in the BAL of HIV-infected patients; and (6) in nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs, healthy frequencies of Th17 cells are maintained in the GI tract and blood.

Th17 cells play a critical role in antimicrobial immunity by induction of antibacterial defensins and recruitment of neutrophils.7-9 Moreover, Th17 cells may play a role in GI enterocyte homeostasis.8,9 Chronic HIV infection is characterized by systemic depletion of CD4 T cells45 that begins with the massive depletion of gastrointestinal CD4 T cells during the acute phase of infection,32-34 increased intestinal permeability and enteropathy,46 and chronic activation of the immune system, which is a significant predictor of disease progression.47-51 One consequence of the adverse events that occur in the GI tract during HIV infection is translocation of immunostimulatory microbial products, which then directly stimulate the immune system in vivo.18,19 The preferential and sustained loss of Th17 cells from the HIV-infected GI tract could therefore have a deleterious effect on the maintenance of the mucosal barrier, both structurally and immunologically, with reduced control of mucosal microbes ensuing and rendering the patient particularly susceptible to microbial translocation. Indeed, a recent study has shown that CD4 T cells from patients with dominant negative stat3 gene mutations are unable to differentiate into Th17 cells in vivo, which renders these patients exquisitely susceptible to bacterial infections.52

Although Th17 cells are not preferentially infected by HIV compared with Th1 cells in PB, the specific loss of CCR5+ Th17 cells in the GI tract supports a direct role for the virus in their preferential loss of Th17 cells from the GI tract. In addition, we propose that the low frequencies of APC we observed within the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients may contribute to an altered cytokine environment that would favor the differentiation of CD4 T cells along a Th1 rather than a Th17 pathway.53

Consistent with the supposition that preferential loss of Th17 cells is an important aspect of pathogenic lentiviral infection, Th17 cells are similarly lost from effector tissues in SIV-infected rhesus macaques.21 However, SMs, which become similarly depleted of GI tract CD4 T cells during the acute phase of SIV infection but do not progress to AIDS, do not manifest preferential loss of Th17 cells. These animals are therefore presumably able to maintain Th17 cell frequencies above a certain threshold, such that the structural and immunologic integrity of the GI tract remains intact. Hence, preferential loss of GI tract Th17 cells appears to be a hallmark of progressive HIV/SIV infection. Although the depletion of both Th1 and Th17 subsets is probably paramount in the pathogenesis of HIV infection, the particular depletion of Th17 cells at the mucosal surface, by virtue of their antigen specificity, may be the more critical in determining bacterial control and microbial translocation, and thus the pace of HIV disease progression. The mechanisms that underlie such Th17 cell loss in the GI tract, and the relationship of this phenomenon to GI tract integrity and microbial translocation, might be central to the development of therapeutic interventions that modify the consequences of damage to the GI tract and, by extension, disease progression.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Beth Zwickl, Mitchell Goldman, and Jeff Waltz for patient referral, and the Indiana University General Clinical Research Center for patient care.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI052755 and AI066998, the Yerkes Primate Center (RR-00165), and the W.W. Smith Charitable Trust (G.S.); NIH grants R01 AI54232, K24 AI056986, and R01 DE-12934 (T.W.S.); and NIH grants K08HL04545-05 and R01 HL083468 (K.S.K.). D.A.P. is a Medical Research Council (UK) Senior Clinical Fellow. This work was supported in part by the intramural program of NIAID, NIH.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.M.B., M.P., A.I.A., B.C., T.E.A., P.S., and D.A.P. performed the experiments; J.M.B., M.P., G.S., and D.C.D. analyzed the data and conceived the study; and K.S.K., C.A.H., L.M.K., A.K., I.F., J.E., and T.S. procured patient and/or animal samples and recruited and cared for study subjects.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jason M. Brenchley, Human Immunology Section, VRC, Room 301, Building 4, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: jbrenchl@mail.nih.gov; or Daniel C. Douek, Human Immunology Section, VRC, Room 3509, Building 40, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: ddouek@nih.gov.

References

Author notes

*J.M.B. and M.P. as well as G.S. and D.C.D. contributed equally to this study.