Abstract

Nucleic acid–based vaccines are effective in infectious disease models but have yielded disappointing results in tumor models when tumor-associated self-antigens are used. Incorporation of helper epitopes from foreign antigens into tumor vaccines might enhance the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines without increasing toxicity. However, generation of fusion constructs encoding both tumor and helper antigens may be difficult, and resulting proteins have unpredictable physical and immunologic properties. Furthermore, simultaneous production of equal amounts of highly immunogenic helper and weakly immunogenic tumor antigens in situ could favor development of responses against the helper antigen rather than the antigen of interest. We assessed the ability of 2 helper antigens (β-galactosidase or fragment C of tetanus toxin) encoded by one plasmid to augment responses to a self-antigen (lymphoma-associated T-cell receptor) encoded by a separate plasmid after codelivery into skin by gene gun. This approach allowed adjustment of the relative ratios of helper and tumor antigen plasmids to optimize helper effects. Incorporation of threshold (minimally immunogenic) amounts of helper antigen plasmid into a DNA vaccine regimen dramatically increased T cell–dependent protective immunity initiated by plasmid-encoded tumor-associated T-cell receptor antigen. This simple strategy can easily be incorporated into future vaccine trials in experimental animals and possibly in humans.

Introduction

Plasmid-encoded antigens have been used to induce immune responses in experimental animals and humans for more than a decade. Plasmid-based nucleic acid vaccines are attractive because of simplicity, low cost, and safety, but suboptimal immunogenicity and limited efficacy against certain pathogens and tumors have limited their utility. A variety of strategies have been developed to enhance DNA vaccine efficacy. These approaches include: (1) modification of DNA vaccines to include improved expression plasmids1 or incorporation of viral vectors2 ; (2) modifications of cDNA sequences encoding antigen to enhance antigenicity,3 codon adjustments to optimize transcription,1,4 or generation of string-of-epitope constructs incorporating selected subunits of antigens5,6 ; (3) improved delivery systems, including methods for more efficient in vivo transfection of host cells, such as in vivo electroporation6 or gene gun7 ; and (4) the use of adjuvants.8 Adjuvants include conventional adjuvants, such as Freund adjuvant, and the more recently developed chemically defined (“molecular”) adjuvants. The latter are intended to enhance immune responses while avoiding, or at least significantly reducing, adverse effects associated with conventional adjuvants.

Entities with a wide variety of biologic effects have been used as chemically defined adjuvants for DNA vaccines, including biologic response modifiers such as cytokines (eg, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF]9 ) and costimulatory molecules10,11 as well as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that block undesired or trigger desired pathways, such as anti-CD4012 or anti-CD137.13 An alternative strategy involves codelivery of “helper antigens” (ie, foreign antigens that induce strong T-cell responses) with weak antigens of interest. Helper antigens are selected based on their high immunogenicity and enhance responses to weaker antigens via incompletely characterized bystander effects. Proteins previously used as helper antigens include keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH),14,15 the hepatitis B core and surface proteins, tetanus toxoid,16,17 and (species-mismatched) heat shock proteins (hsp).18 A variant of this approach involves the creation of virus-like particles (VLPs) using virus-derived proteins (from hepatitis19 or human papilloma virus20 ) fused to antigens of interest.

Incorporation of helper antigens into DNA vaccines presents several potential problems. If helper and target antigens are encoded by 2 separate plasmids and delivered by simple injection, uptake and expression from both plasmids by the same antigen-presenting cell (APC) are doubtful. In addition, using a strong helper antigen in conjunction with a weakly immunogenic antigen, such as a tumor-associated self-antigen that is subject to immunologic tolerance, raises the possibility for immunodominance of the stronger over the weaker antigen.21,22 In most studies, the issue of codelivery and coexpression of helper and target antigen has been addressed by generating fusion proteins encoded in a single open reading frame (ORF). Alternatively, the 2 ORFs can be encoded individually on a single bicistronic plasmid23 or separated by an internal ribosomal entry site.24 Using these approaches, it is probable that comparable amounts of the 2 antigens are expressed in transduced APCs, and it is not possible to significantly vary relative levels of expression.

In the present study, we used β-galactosidase (β-gal), a highly immunogenic bacterial protein, encoded by one plasmid, as a helper antigen for a poorly immunogenic β chain of a murine T-cell lymphoma's T-cell receptor (TCR-β), encoded by a separate plasmid. A gene gun was used to cotransfect cells in vivo by cocoating the 2 plasmids onto the same pool of gold particles. We determined that the helper antigen plasmid was largely ineffective when delivered at the same dose as the tumor antigen plasmid but achieved dramatically increased efficacy at a very low β-gal–to–TCR-β plasmid ratio. Similar results were obtained with another helper antigen (fragment C), and low-dose β-gal also functioned as a helper antigen in a melanoma vaccine model. These results suggest that the use of fusion proteins when developing DNA vaccines with strong helper antigens as immune enhancers may be suboptimal and instead support the simpler approach of codelivering the 2 plasmids at an optimized ratio on the same gold particles via gene gun. This will also allow rapid screening of different helper antigens and different helper/target antigen ratios in the probable event that vaccine immunogenicities are antigen-, disease-, and/or species-dependent.

Methods

Plasmids

Full-length cDNAs encoding the TCR-β and TCR-α chains from the T-cell lymphoma cell line RMA25 were prepared using standard molecular genetics methodology as described in Document S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The pSport-β-gal plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was previously used as a DNA vaccine.26 pcDNA-FrC (encoding tetanus fragment C) was a kind gift of Dr Scott Stibitz (Food and Drug Administration/Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Bethesda, MD).27

The pcDNA-gag plasmid (kind gift of Dr Antonio Rosato, University of Padova, Padua, Italy) containing the gag coding sequence of Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) was used as a positive control vaccine.28 pcDNA3.1 without insert (Invitrogen) was used as negative control for the helper plasmid. A plasmid encoding human melanoma antigen gp100 was used for melanoma studies.29 The functionality of the TCR plasmids was tested as described in the supplemental data.

Mice, immunization, and flow cytometry

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee. Female C57BL/6 mice (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD) were used at 6 to 8 weeks of age and immunized 5 times at weekly intervals via shaved abdominal skin with 3 nonoverlapping shots of plasmid-coated gold particles (1 μm diameter; DeGussa, Parsippany, NY) using the Helios gene gun (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). This regimen was previously developed for another self-antigen30 and proved to be more efficacious for the TCR plasmid vaccine described herein than 3 immunizations at 3-week intervals (data not shown). TCR and helper plasmids were coprecipitated onto gold particles as described7 at various ratios maintaining a calculated TCR-plasmid dose of 1 μg/shot and doses of the adjuvant or control plasmids that ranged from 1 μg to 0.3 ng/shot.

To determine the impact of immunization on the endogenous T-cell repertoire, peripheral blood leukocytes from immunized mice were double-stained with anti-CD3 antibody (clone 145-2C11; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and anti-Vβ12 antibody (clone MR11-1; BD PharMingen) or anti-Vβ10 antibody (clone B21.5; BD PharMingen) and cell frequencies were assessed via flow cytometry. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen expression on tumor cells was detected using mAbs from BD PharMingen (clone AF6-88.5 for H-2Kb and clone AF6-120.1 for I-Ab) followed by flow cytometric analysis.

Tumor challenge experiments

MBL-2 lymphoma cells (kind gift of Dr Antonio Rosato, University of Padova, Padua, Italy)28 were assessed for surface expression of CD4, CD8, MHC-I (H-2Kb, H-2Db), MHC-II (I-Ab), and TCR by flow cytometry (antibodies from BD PharMingen). Tumors were initiated by subcutaneous injection into flank skin 7 to 10 days after the last immunization (105 tumor cells/mouse). Tumor growth was quantified in 2 perpendicular dimensions using calipers, and mice were killed when tumors reached sizes of 2 cm in the greatest dimension. MBL-2 cells express the same TCR as RMA cells (data not shown, and van Hall et al25 ) and were used because they yielded more reliable challenge results than RMA cells. The melanoma challenge with B10.F10 cells has previously been described.30

To characterize vaccine effector mechanisms, T-cell populations were depleted in vivo as previously described30 (supplemental data). The C57BL/6 T-cell lymphoma C6VL (kind gift of Dr Craig Y. Okada, Portland VA Medical Center, Portland, OR) was used as a specificity control because it expresses a TCR different from that on MBL-2 (and related) cells.31

ELIspot assays

Splenocytes from immunized mice were obtained one week after the last immunization and cryopreserved until assessment. IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELIspot) assays were performed as described in the supplemental data.

β-gal ELISA

Serum levels of β-gal–specific antibodies were determined as described.32 Sera were obtained 1 week after the last immunization. Serum from mice immunized twice (3-week interval) with 1 μg pSport–β-gal plasmid/shot was used as a positive control.

Results

Tumor antigen expression

Full-length cDNAs encoding TCR-α and TCR-β chains from the C57BL/6-derived T-cell lymphoma RMA (same TCR as on MBL-2 and EL-4 lymphomas)25 were inserted into expression plasmids. Recombinant TCR-β chain was detected in pVax-TCR-β–transfected BHK-21 cells using a Vβ12-specific mAb (Figure S1A) as well as a pan-β chain–specific Ab (not shown) intracellularly, but not on cell surfaces (Figure S1B). Expression of the TCR-α chain in pVax-TCR-α transfectants was also detected with a pan-alpha chain–specific mAb only after fixation and permeabilization (not shown). Cotransfection with a mixture of TCR-β and β-gal plasmids resulted in coexpression of both chains intracellularly, but not on cell surfaces (data not shown). In contrast, TCR was readily detected on the surfaces of MBL-2 cells (Figure S1C). Additional characterization of MBL-2 cells revealed expression of MHC-I (H-2Db, H-2Kb), but not MHC-II (I-Ab) antigens (Figure S1D), making them potential targets for CD8, but not CD4 effector T cells. MBL-2 T cells express neither CD4 nor CD8 (not shown).

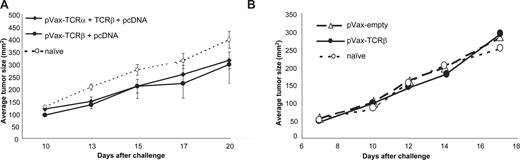

Vaccination with plasmids encoding TCR alone did not protect against tumor progression

C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated with TCR-encoding plasmids using immunization regimens previously established in other tumor models. Mice received 5 rounds of 3 shots by gene gun (Figure 1A) or intradermal injections of 50 μg plasmid 5 times (Figure 1B) at weekly intervals. Immunization with pVax-TCR-β, alone or in combination with pVax-TCR-α, did not significantly affect the growth of subcutaneously injected MBL-2 cells, whereas immunization with a gag-encoding plasmid by gene gun (Figures 2,3; Table S1) or intramuscularly (not shown, and Milan et al28 ) induced complete or almost complete tumor protection. MBL-2 cells carry the Moloney murine leukemia virus and express viral gag protein.28 Therefore, we used pcDNA-gag as a positive control in our experiments.

Ability of TCR-encoding plasmids to vaccinate against T-cell lymphoma. (A) Mice were immunized 5 times at weekly intervals by gene gun with pVax-plasmids encoding the α chain alone (not shown), β chain alone (●), or with a combination of both delivered on the same gold particles (♦) followed by tumor challenge with 105 subcutaneously implanted MBL-2 lymphoma cells (mean ± SEM of 6 mice/group). The finding was confirmed in 7 independent experiments. (B) To examine the impact of the route of delivery on tumor protection, TCR-β–plasmid (50 μg plasmid/immunization) was injected intradermally 5 times at weekly intervals followed by MBL-2 tumor challenge as in panel A (n = 10 mice/group). Representative data from 1 of 2 experiments are shown (mean ± SEM).

Ability of TCR-encoding plasmids to vaccinate against T-cell lymphoma. (A) Mice were immunized 5 times at weekly intervals by gene gun with pVax-plasmids encoding the α chain alone (not shown), β chain alone (●), or with a combination of both delivered on the same gold particles (♦) followed by tumor challenge with 105 subcutaneously implanted MBL-2 lymphoma cells (mean ± SEM of 6 mice/group). The finding was confirmed in 7 independent experiments. (B) To examine the impact of the route of delivery on tumor protection, TCR-β–plasmid (50 μg plasmid/immunization) was injected intradermally 5 times at weekly intervals followed by MBL-2 tumor challenge as in panel A (n = 10 mice/group). Representative data from 1 of 2 experiments are shown (mean ± SEM).

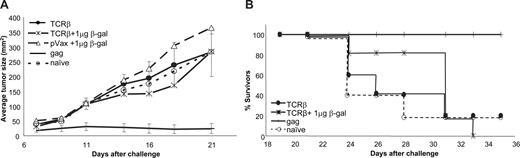

Codelivery of equal amounts of antigen plasmid and helper plasmid did not enhance the immunogenicity of TCR-β cDNA. (A) TCR-β plasmid (1 μg/shot) was coprecipitated onto gold particles with the same amount of β-gal plasmid and delivered to mice by gene gun followed by subcutaneous MBL-2 tumor challenge. Tumor sizes (mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice/group) are shown for naive mice (○), mice immunized with the empty vector plus β-gal (△), and mice immunized with TCR-β plus β-gal plasmids ( ). Plasmid pcDNA-gag served as a positive control (n = 5 mice/group). Experiments were terminated when more than 50% of the mice in a group had been humanely killed. (B) Survival of mice after gene gun delivery of TCR-β (with or without an equal amount of β-gal plasmid) or gag-encoding plasmids and subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor.

). Plasmid pcDNA-gag served as a positive control (n = 5 mice/group). Experiments were terminated when more than 50% of the mice in a group had been humanely killed. (B) Survival of mice after gene gun delivery of TCR-β (with or without an equal amount of β-gal plasmid) or gag-encoding plasmids and subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor.

Codelivery of equal amounts of antigen plasmid and helper plasmid did not enhance the immunogenicity of TCR-β cDNA. (A) TCR-β plasmid (1 μg/shot) was coprecipitated onto gold particles with the same amount of β-gal plasmid and delivered to mice by gene gun followed by subcutaneous MBL-2 tumor challenge. Tumor sizes (mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice/group) are shown for naive mice (○), mice immunized with the empty vector plus β-gal (△), and mice immunized with TCR-β plus β-gal plasmids ( ). Plasmid pcDNA-gag served as a positive control (n = 5 mice/group). Experiments were terminated when more than 50% of the mice in a group had been humanely killed. (B) Survival of mice after gene gun delivery of TCR-β (with or without an equal amount of β-gal plasmid) or gag-encoding plasmids and subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor.

). Plasmid pcDNA-gag served as a positive control (n = 5 mice/group). Experiments were terminated when more than 50% of the mice in a group had been humanely killed. (B) Survival of mice after gene gun delivery of TCR-β (with or without an equal amount of β-gal plasmid) or gag-encoding plasmids and subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor.

Augmentation of vaccine efficacy by small amounts of helper antigen plasmid when codelivered with TCR-β plasmid. (A) Mice were immunized 5 times with gold particles carrying a fixed amount of TCR-β plasmid (1 μg/shot) and various amounts of β-gal plasmid (33 ng to 0.3 ng/shot) followed by subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor cells. (B) To test whether tumor protection is dependent on TCR-β cDNA or a nonspecific effect of β-gal DNA or any plasmid DNA, mice were immunized with TCR-β plasmid plus helper plasmid ( ), TCR-β plasmid plus empty vector (▲), empty vaccine vector (pVax) plus helper plasmid (6 ng β-gal/shot, △), or pcDNA-gag as a positive control (no symbol). (C) Survival of mice immunized with gold particles carrying coprecipitated TCR-β and β-gal (n = 8 mice/group) after challenge with subcutaneous MBL-2 cells. Similar data were obtained in 17 independent experiments in which TCR-β plus 6 ng β-gal was used as a positive control for other experimental lymphoma vaccines. Survival data from all experiments are summarized in Table S1. (D) To demonstrate that the “helper-effect” was not restricted to β-gal, gold particles carrying 1 μg TCR-β–encoding plasmid and 6 ng helper antigen-encoding plasmid (β-gal or fragment C of tetanus toxin) were used to immunize mice (n = 8/group) before subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor cells. As a control, mice were immunized with the TCR-β plasmid plus low-dose empty pcDNA vector or with empty pVax vector plus low-dose pVax plasmid. Representative data from 1 of 2 experiments are shown (mean ± SEM).

), TCR-β plasmid plus empty vector (▲), empty vaccine vector (pVax) plus helper plasmid (6 ng β-gal/shot, △), or pcDNA-gag as a positive control (no symbol). (C) Survival of mice immunized with gold particles carrying coprecipitated TCR-β and β-gal (n = 8 mice/group) after challenge with subcutaneous MBL-2 cells. Similar data were obtained in 17 independent experiments in which TCR-β plus 6 ng β-gal was used as a positive control for other experimental lymphoma vaccines. Survival data from all experiments are summarized in Table S1. (D) To demonstrate that the “helper-effect” was not restricted to β-gal, gold particles carrying 1 μg TCR-β–encoding plasmid and 6 ng helper antigen-encoding plasmid (β-gal or fragment C of tetanus toxin) were used to immunize mice (n = 8/group) before subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor cells. As a control, mice were immunized with the TCR-β plasmid plus low-dose empty pcDNA vector or with empty pVax vector plus low-dose pVax plasmid. Representative data from 1 of 2 experiments are shown (mean ± SEM).

Augmentation of vaccine efficacy by small amounts of helper antigen plasmid when codelivered with TCR-β plasmid. (A) Mice were immunized 5 times with gold particles carrying a fixed amount of TCR-β plasmid (1 μg/shot) and various amounts of β-gal plasmid (33 ng to 0.3 ng/shot) followed by subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor cells. (B) To test whether tumor protection is dependent on TCR-β cDNA or a nonspecific effect of β-gal DNA or any plasmid DNA, mice were immunized with TCR-β plasmid plus helper plasmid ( ), TCR-β plasmid plus empty vector (▲), empty vaccine vector (pVax) plus helper plasmid (6 ng β-gal/shot, △), or pcDNA-gag as a positive control (no symbol). (C) Survival of mice immunized with gold particles carrying coprecipitated TCR-β and β-gal (n = 8 mice/group) after challenge with subcutaneous MBL-2 cells. Similar data were obtained in 17 independent experiments in which TCR-β plus 6 ng β-gal was used as a positive control for other experimental lymphoma vaccines. Survival data from all experiments are summarized in Table S1. (D) To demonstrate that the “helper-effect” was not restricted to β-gal, gold particles carrying 1 μg TCR-β–encoding plasmid and 6 ng helper antigen-encoding plasmid (β-gal or fragment C of tetanus toxin) were used to immunize mice (n = 8/group) before subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor cells. As a control, mice were immunized with the TCR-β plasmid plus low-dose empty pcDNA vector or with empty pVax vector plus low-dose pVax plasmid. Representative data from 1 of 2 experiments are shown (mean ± SEM).

), TCR-β plasmid plus empty vector (▲), empty vaccine vector (pVax) plus helper plasmid (6 ng β-gal/shot, △), or pcDNA-gag as a positive control (no symbol). (C) Survival of mice immunized with gold particles carrying coprecipitated TCR-β and β-gal (n = 8 mice/group) after challenge with subcutaneous MBL-2 cells. Similar data were obtained in 17 independent experiments in which TCR-β plus 6 ng β-gal was used as a positive control for other experimental lymphoma vaccines. Survival data from all experiments are summarized in Table S1. (D) To demonstrate that the “helper-effect” was not restricted to β-gal, gold particles carrying 1 μg TCR-β–encoding plasmid and 6 ng helper antigen-encoding plasmid (β-gal or fragment C of tetanus toxin) were used to immunize mice (n = 8/group) before subcutaneous challenge with MBL-2 tumor cells. As a control, mice were immunized with the TCR-β plasmid plus low-dose empty pcDNA vector or with empty pVax vector plus low-dose pVax plasmid. Representative data from 1 of 2 experiments are shown (mean ± SEM).

Only low-dose helper plasmid provided an adjuvant effect for the TCR-based DNA vaccine

Various highly immunogenic proteins have been used as helper antigens in the form of fusion proteins. To approximate the effect of administering a plasmid encoding a fusion protein containing helper epitopes, individual plasmids encoding TCR and the helper antigens were codelivered by gene gun to cells in skin on gold particles carrying both plasmids. This approach eliminated potential problems associated with the translation of very large proteins potentially resulting in truncated products as well as possible misfolding of novel fusion proteins. Gold particles carrying a calculated maximal dose of 1 μg TCR-plasmid plus 1 μg β-gal plasmid/shot, and delivered 5 times at weekly intervals, did not result in greater protective immunity than a vaccine composed of gold particles carrying the TCR plasmid and empty vector. Tumor growth in both groups also did not differ from tumor growth in mice treated with empty pVax plasmid coprecipitated on gold particles together with β-gal–“helper” plasmid (Figure 2A), and delivery of equal amounts of “tumor antigen plasmid” and “helper plasmid” did not prolong the survival of mice after tumor challenge (Figure 2B).

To address the possibility that the β-gal plasmid interfered with the expression of TCR from the second plasmid, we transfected BHK-21 cells with the 2 plasmids simultaneously. Comparable levels of TCR protein were detected in BHK-21 cells cotransfected with TCR-plasmid and β-gal plasmid or TCR plasmid and empty vector (data not shown).

We sought to determine whether the lack of an adjuvant effect of β-gal was the result of dose rather than the nature of the helper antigen. Indeed, tumor growth was consistently reduced in mice immunized with gold particles carrying constant amounts of TCR-plasmid (calculated maximal dose of 1 μg/shot) and lesser amounts of β-gal plasmid (Figure 3A). The adjuvant effect increased as amounts of β-gal plasmid decreased with a maximum effect at a β-gal dose of 1.3 ng plasmid/shot (P < .001, Mann-Whitney test). Optimal doses of β-gal plasmid were not identical in different experiments, perhaps because particle coating efficiencies at very low β-gal–plasmid concentrations varied. As previously described, gold particles used for gene gun immunization are not uniformly coated with DNA even when using “standard” amounts (ie, 1 μg DNA/shot) of plasmid.33 Nevertheless, threshold amounts of β-gal plasmid (ie, < 100 ng plasmid/shot and as little as 1.3 ng plasmid/shot) consistently and reproducibly reduced tumor growth in each experiment (n = 17 independent experiments with 5-8 mice/group). This effect required coexpression of TCR-β and β-gal because immunization with empty pVax vector at 1 μg/shot in conjunction with 1.3 ng β-gal plasmid did not reduce tumor growth compared with mice immunized with pVax-TCR-β plus control plasmid or naive animals (P = .4, Mann-Whitney test; Figure 3B).

In addition to reducing tumor sizes, coimmunization with small amounts of β-gal plasmid significantly increased the survival of tumor-bearing mice (P = .01 for TCR-β with 6 ng β-gal plasmid and P < .01 for TCR-β plus lower doses of the helper plasmid, compared with pVax-TCR-β + pcDNA, Wilcoxon rank sum test; Figure 3C; Table S1), whereas β-gal plasmid at any concentration together with empty pVax vector did not have a significant impact on survival (not shown). The helper effect of a foreign protein was not restricted to β-gal but could also be achieved with another highly immunogenic protein, fragment C of the tetanus toxin, codelivered at a 1:150 ratio with pVax-TCR-β (Figure 3D). Protection was tumor antigen-specific because β-gal plasmid (6 ng/shot) did not impact on the growth of a distinct syngeneic T-cell lymphoma (C6VL) when codelivered with TCR-β(MBL-2) (Figure S2). Finally, the helper effect of low doses of helper antigen was not restricted to lymphoma, but β-gal plasmid also improved the efficacy of a gp100-encoding plasmid used to induce protective immune responses against a B16 melanoma (Figure S3).

Helper antigen increased tumor-specific T-cell responses but did not adversely affect the endogenous T-cell repertoire

The adjuvant effect of the helper antigen was TCR antigen-dependent because codelivery of empty pVax plasmid together with β-gal plasmid did not affect tumor growth or survival of MBL-2–challenged mice (P = .4; Figures 2A,B, 3A,B; Table S1). We next asked whether helper antigen led to an increase in the number of tumor-reactive T cells in vaccine recipients. Splenocytes obtained from mice that had been immunized in parallel but not challenged with tumor cells were incubated with cell lines expressing the TCR targeted by the vaccine (MBL-2 lymphoma) or the helper antigen (β-gal peptide-pulsed MC-38 [designated MC-38 + β-gal peptide] or stable β-gal MC-38 transfectants [Z17 cells]). Although numbers of IFN-γ ELIspots varied up to 4-fold between experiments, mice that had been coimmunized with TCR-β plasmid, and threshold amounts of β-gal plasmid consistently showed higher T-cell reactivity than mice that received TCR-β plasmid and high amounts of β-gal plasmid. All ELIspot experiments were conducted with unfractionated splenocytes to avoid introducing in vitro artifacts and in an effort to replicate the cellular composition of an in vivo immune or inflammatory infiltrate. Specificity of the responses was determined by the choice of target (ie, CD8 restriction resulting from the use of MHC-I–binding peptides or the use of T-cell lymphomas that do not express MHC-II).

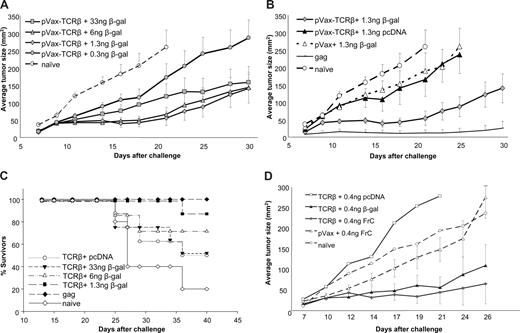

Delivery of β-gal plasmid (33 ng/shot) on gold particles that were cocoated with TCR-β plasmid (1 μg/shot) led to a significant increase in the number of IFN-γ–producing T cells reactive with MBL-2 target cells (P < .01 by Mann-Whitney test for both doses of β-gal; Figure 4A). Larger amounts of β-gal plasmid did not provide any adjuvant effect despite the elicitation of stronger β-gal–specific T-cell responses (166-ng group in Figure 5A; 1-μg group in Figure 4C). Enhancement of TCR-specific T-cell responses by small amounts of β-gal plasmid was also evident when TCR-α (0.5 μg/shot), TCR-β (0.5 μg/shot), and β-gal plasmid (33 ng/shot) were codelivered. However, the adjuvant effect of the β-gal plasmid was lost at higher doses (0.5 μg/shot; Figure 4B). Interestingly, the magnitude of maximal MBL-2–reactive ELIspot responses stimulated by TCR-β/β-gal plasmid vaccines was comparable with that seen after genetic immunization with the gag-expression plasmid (Figure 4B). Within a range, the adjuvant effect of the coprecipitated β-gal plasmid correlated inversely with the magnitude of the T-cell response to β-gal as measured by IFN-γ ELIspots produced by splenocytes stimulated ex vivo with β-gal targets (compare Figure 3A with Figure 4C). No β-gal–specific T-cell response was detected after immunization with particles carrying 0.3 ng β-gal plasmid/shot (Figure 4C); and at this dose, the adjuvant effect also disappeared in tumor challenge experiments (Figure 3A). Although a significant β-gal–specific T-cell response (Figure 4C) was induced with a β-gal plasmid dose of 6 ng/shot (ie, the dose used for all subsequent experiments), no β-gal–specific antibodies were detected at this dose (Figure S4).

In vitro assessment of immune responses induced by the TCR-DNA vaccines. (A) Mice were immunized as in Figure 3 with the TCR-β plasmid plus the β-gal plasmid (33 or 166 ng β-gal/shot) or with pcDNA-gag, and tumor cell (MBL)–reactive T cells were detected ex vivo by IFN-γ ELIspot using unfractionated splenocytes. Data (mean ± SEM) are from 3 to 6 mice per group (quadruplicate wells). Target cells presenting β-gal (peptide-pulsed MC-38 or β-gal–transfected Z17 cells) were used to monitor the anti–β-gal response that was induced by the helper plasmid. (B) As in panel A, mice were coimmunized with β-gal, but a mixture of TCR-α and TCR-β plasmids was delivered using β-gal plasmid at a “high dose” (500 ng/shot) or a “low dose” (33 ng/shot). Splenocytes from mice immunized with pcDNA-gag served as a positive control (mean ± SEM of n = 3 mice/group). (C) β-gal–specific T-cell response in mice receiving TCR-β plasmid and titered amounts of β-gal helper plasmid as measured by IFN-γ ELIspot.

In vitro assessment of immune responses induced by the TCR-DNA vaccines. (A) Mice were immunized as in Figure 3 with the TCR-β plasmid plus the β-gal plasmid (33 or 166 ng β-gal/shot) or with pcDNA-gag, and tumor cell (MBL)–reactive T cells were detected ex vivo by IFN-γ ELIspot using unfractionated splenocytes. Data (mean ± SEM) are from 3 to 6 mice per group (quadruplicate wells). Target cells presenting β-gal (peptide-pulsed MC-38 or β-gal–transfected Z17 cells) were used to monitor the anti–β-gal response that was induced by the helper plasmid. (B) As in panel A, mice were coimmunized with β-gal, but a mixture of TCR-α and TCR-β plasmids was delivered using β-gal plasmid at a “high dose” (500 ng/shot) or a “low dose” (33 ng/shot). Splenocytes from mice immunized with pcDNA-gag served as a positive control (mean ± SEM of n = 3 mice/group). (C) β-gal–specific T-cell response in mice receiving TCR-β plasmid and titered amounts of β-gal helper plasmid as measured by IFN-γ ELIspot.

T-cell dependence of TCR-plasmid–induced tumor protection. (A) Plasmid-immunized mice (1 μg TCR-β + 6 ng β-gal/shot) received anti-CD4 (□) or anti-CD8 (○) depleting antibodies 2 days before subcutaneous tumor challenge with 105 MBL-2 cells. Shown are average tumor sizes (n = 8 mice/group) with SE. (B) Survival of TCR-β plus β-gal–immunized mice challenged with MBL-2 tumor cells after (“acute”) depletion of effector CD4 or CD8 cells. (C) To examine the requirement for codelivery of tumor-antigen plasmid and helper plasmid, mice (n = 8/group) were immunized with gold particles carrying both plasmids ( ), with a mixture of gold particles separately coated with the 2 plasmids (

), with a mixture of gold particles separately coated with the 2 plasmids ( ) or by delivering the 2 plasmids to 2 separate sites on the mice (

) or by delivering the 2 plasmids to 2 separate sites on the mice ( ). (D) Tumor challenge resulted in epitope spreading. Splenocytes from TCR-β–plasmid immunized challenge survivors (ie, tumor free at least 3 weeks after challenge with MBL-2 cells subcutaneously) or splenocytes from pcDNA-immunized but not tumor-challenged mice were tested in ELIspot assays for their antigen specificity. Target cells (MC-38) were pulsed with gag-peptide, or a gag-negative, TCR-mismatched T-cell lymphoma (C6VL) was used to detect challenge-induced gag-specific T cells. Shown are IFN-γ–ELIspot results from individual mice (average of triplicate wells).

). (D) Tumor challenge resulted in epitope spreading. Splenocytes from TCR-β–plasmid immunized challenge survivors (ie, tumor free at least 3 weeks after challenge with MBL-2 cells subcutaneously) or splenocytes from pcDNA-immunized but not tumor-challenged mice were tested in ELIspot assays for their antigen specificity. Target cells (MC-38) were pulsed with gag-peptide, or a gag-negative, TCR-mismatched T-cell lymphoma (C6VL) was used to detect challenge-induced gag-specific T cells. Shown are IFN-γ–ELIspot results from individual mice (average of triplicate wells).

T-cell dependence of TCR-plasmid–induced tumor protection. (A) Plasmid-immunized mice (1 μg TCR-β + 6 ng β-gal/shot) received anti-CD4 (□) or anti-CD8 (○) depleting antibodies 2 days before subcutaneous tumor challenge with 105 MBL-2 cells. Shown are average tumor sizes (n = 8 mice/group) with SE. (B) Survival of TCR-β plus β-gal–immunized mice challenged with MBL-2 tumor cells after (“acute”) depletion of effector CD4 or CD8 cells. (C) To examine the requirement for codelivery of tumor-antigen plasmid and helper plasmid, mice (n = 8/group) were immunized with gold particles carrying both plasmids ( ), with a mixture of gold particles separately coated with the 2 plasmids (

), with a mixture of gold particles separately coated with the 2 plasmids ( ) or by delivering the 2 plasmids to 2 separate sites on the mice (

) or by delivering the 2 plasmids to 2 separate sites on the mice ( ). (D) Tumor challenge resulted in epitope spreading. Splenocytes from TCR-β–plasmid immunized challenge survivors (ie, tumor free at least 3 weeks after challenge with MBL-2 cells subcutaneously) or splenocytes from pcDNA-immunized but not tumor-challenged mice were tested in ELIspot assays for their antigen specificity. Target cells (MC-38) were pulsed with gag-peptide, or a gag-negative, TCR-mismatched T-cell lymphoma (C6VL) was used to detect challenge-induced gag-specific T cells. Shown are IFN-γ–ELIspot results from individual mice (average of triplicate wells).

). (D) Tumor challenge resulted in epitope spreading. Splenocytes from TCR-β–plasmid immunized challenge survivors (ie, tumor free at least 3 weeks after challenge with MBL-2 cells subcutaneously) or splenocytes from pcDNA-immunized but not tumor-challenged mice were tested in ELIspot assays for their antigen specificity. Target cells (MC-38) were pulsed with gag-peptide, or a gag-negative, TCR-mismatched T-cell lymphoma (C6VL) was used to detect challenge-induced gag-specific T cells. Shown are IFN-γ–ELIspot results from individual mice (average of triplicate wells).

pVax-TCR–induced T-cell responses appear to be directed against the TCR of the targeted lymphoma only because syngeneic T-cell lymphoma cells (C6VL) expressing an unrelated TCR were not recognized by splenocytes from mice immunized with MBL-2–derived pVax–TCR-β (Figure S2). Although this suggested that DNA vaccine-induced immune responses were not directed against the constant region of the TCR, it remained possible that endogenous host T cells expressing TCRs of the same variable-chain subfamily (Vβ12) as the lymphoma might be targets and deleted. To address this question, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from immunized mice and stained with anti-Vβ12 (relevant TCR) or anti-Vβ10 mAb (irrelevant TCR). Immunization with plasmids encoding Vβ12-TCR did not result in deletion of Vβ12+ or Vβ10+ T cells (Figure S5), suggesting that DNA vaccine-induced immune responses were directed only, or at least predominantly, against unique epitopes within the hypervariable region of the lymphoma's TCR.

The TCR-encoding DNA vaccine induced effector T cells but not humoral immune responses

Previously described TCR-based DNA17,34 and TCR-recombinant protein35,36 vaccines induced significant humoral immune responses. In contrast, our pVax–TCR-β plasmid did not stimulate measurable Ab responses against TCR on MBL-2 cells as determined by flow cytometry, even when coadministered with optimal amounts of β-gal plasmid (data not shown). Thus, we focused on the role of T-cell subpopulations in protective immunity after vaccination. Because of their lineage, MBL-2 cells do not express MHC-II antigens as confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure S1D); thus, the ELIspot experiments (Figure 4A,B) are only informative with regard to lymphoma-reactive CD8 T cells. To address direct as well as indirect contributions of CD4 and CD8 T cells to tumor protection, endogenous CD4+ or CD8+ cells were depleted from immunized mice beginning 2 days before tumor challenge by administering appropriate depleting mAb. Depletion of either CD4 or CD8 cells at the effector stage (“acute depletion”) virtually eliminated the protective effect of pVax–TCR-β/6 ng β-gal plasmid. Tumor growth in CD4- or CD8-depleted animals was comparable (determined by Mann-Whitney test at several time points after challenge) to that occurring in antibody-depleted control mice (empty pVax and β-gal plasmid; Figure 5A). Both treatments also significantly reduced the survival of tumor-bearing mice (P = .027 for anti-CD4, and P = .013 for anti-CD8, compared with control Ig, Wilcoxon rank sum test), indicating a role for both T-cell subsets in vaccine-induced protection (Figure 5B). Depletion of either T-cell population throughout the immunization regimen (“chronic depletion”) reduced but did not abrogate vaccine efficacy (data not shown). Interpretation of results obtained with anti-CD4 antibody in this experiment is complicated because CD4-cell depletion during immunization in the negative control group (pVax/β-gal) unexpectedly attenuated tumor growth suggesting depletion of regulatory T cells.

Maximal adjuvant effects required expression of helper antigen and tumor antigen by the same cells

Coprecipitation of multiple plasmids onto pools of gold particles allowed for codelivery of multiple antigens in a single shot, but it was unclear if the observed adjuvant effect required that both antigens be expressed by the same transfected cells. To further characterize the mechanism of the adjuvant effect provided by β-gal plasmids, we immunized mice with gold particles carrying both plasmids or mixtures of gold particles carrying single plasmids. Because the frequency of direct transfection of APCs in skin after gene gun bombardment is very low,37,38 delivery of mixtures of gold particles coated separately with TCR-β or β-gal plasmids probably resulted in host cells expressing either one or the other antigen. Mice were also immunized with the 2 plasmids on separate gold particles delivered at nonoverlapping sites (left and right flank skin).

Codelivery of the 2 plasmids on same gold particles yielded the highest vaccine efficacy, resulting in significantly reduced tumor growth compared with all other regimens (Figure 5C; P = .03 comparing separate and codelivery of pVax–TCR-β and the β-gal plasmid, Mann-Whitney test, day 14; P = .001 comparing the codelivered plasmid group with naive controls). Vaccination with mixtures of gold particles carrying the TCR or β-gal plasmids on separate particles delivered into the same site was also effective, but less so. Vaccine efficacy was even lower after immunization with TCR-plasmid–coated gold particles in one flank and β-gal plasmid–coated gold particles in the other flank. Indeed, tumor growth in mice immunized with the 2 plasmids in separate sites was not statistically different from tumor growth in naive mice.

Immunization with TCR DNA vaccine led to epitope spreading

Relatively large SEs observed in the tumor challenge experiments at later time points (Figures 1,Figure 2–3) result, at least in part, from the fact that some MBL-2 tumors, which initially grew comparably in all immunized mice, grew to maximum acceptable sizes, whereas others regressed. We also noticed higher tumor rejection rates in challenge experiments in which overall tumor growth was slower (data not shown). Therefore, we hypothesized that tumor-associated antigens, besides TCR, become rejection antigens after tumor challenge. A possible target for epitope spreading is the murine leukemia virus (muLV)–derived gag antigen that acts as a rejection antigen on muLV-induced sarcomas.28 Indeed, immunization with gag-plasmids induced strong protection against muLV+ lymphomas (Figures 2,3B,C; Table S1).28 Using MC-38 cells pulsed with the immunodominant MHC class I–restricted gag-CTL peptide39 as ELIspot targets, we determined that the number of gag86-93-specific IFN-γ–producing T cells was much higher in mice that had cleared MBL-2 tumors after immunization with the TCR-plasmid compared with mice that had been immunized with the gag-encoding plasmid but that had not been challenged with tumor (Figure 5D). C6VL lymphoma cells lacking the gag antigen served as specificity controls for both the TCR-specific and gag-specific immune responses. The ability of the TCR-β/β–gal vaccine to induce tumor rejection did not depend on the development of gag-reactive CD8 cells, however, because the vaccine also protected against engraftment of gag-negative EL-4 lymphoma cells (Figure S6).

Discussion

Expression plasmids have yet to be successfully incorporated into vaccination regimens that prevent or treat disease in humans.40 In the case of cancer immunotherapy, the relative inactivity of plasmid DNA vaccines can be attributed, at least in part, to the poor immunogenicity of tumor antigens. The majority of candidate tumor antigens that have been identified and studied represent normal (self) proteins that are selectively expressed by nonessential cells or tissues (eg, melanocytes or prostatic tissue) or are expressed by a variety of related tumors (eg, carcinomas) but not by most normal tissues.41,42 Thus, the goal of active cancer immunotherapy is to elicit autoimmune responses directed toward subdominant or cryptic determinants that will control tumor growth without unacceptable damage to normal tissues. Various strategies have been used to break tolerance to self (tumor) antigens. Here we demonstrate that adsorption of small amounts of plasmid encoding an exogenous protein (a “helper antigen”) onto gold particles carrying more than 100-fold more of a plasmid encoding a tumor-specific T lymphoma antigen before intracutaneous ballistic delivery converted an ineffective vaccine into one with considerable activity.

β-Galactosidase was chosen as a candidate helper antigen because of its bacterial origin, its large size and associated immunologic complexity, and its potent immunogenicity in mice. Although administration of cDNA encoding the clonotypic β chain of the MBL-2 TCR did not induce an immune response that was sufficient to cause tumor rejection, alone or in combination with cDNA encoding its associated clonotypic TCR-α chain, coadministration of β-gal cDNA dramatically delayed tumor growth. Interestingly, the ability of β-gal cDNA to enhance vaccine effectiveness was dose-dependent with an optimal helper antigen/tumor antigen plasmid ratio of approximately 1:150. High doses of helper antigen plasmid did not augment vaccine efficacy, and doses of helper antigen plasmid that were insufficient to elicit anti–β-gal cellular immune responses also were not active. Because vaccine efficacy was abrogated by either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 mAb treatment, it is not possible to determine whether the vaccine enhancing effects of helper antigen plasmid reflected the involvement of CD4 or CD8 cells, or possibly both. The involvement of CD4 cells at the effector phase in the absence of MHC class II expression by MBL-2 T lymphoma cells is consistent with the concept that tumor antigen-specific help (DC licensing43 ) is required for expression of optimal vaccine efficacy even after CD8 T-cell induction. Using a different tumor cell line that does not constitutively express MHC class II, others also observed a critical role for DNA vaccine-induced CD4 T cells at the effector phase.44 It has been suggested that CD4 tolerance is more stringent than CD8 tolerance,45 so it is tempting to speculate that the effects of β-gal administration are mediated via antigen-reactive CD4 rather than CD8 cells.

Although it has been long known that incorporation of exogenous helper antigens into immunization protocols could break tolerance to self-antigens, contemporary vaccine design has emphasized more reductionist approaches. Tumor antigen–derived, MHC-binding peptides have been optimized,46,47 antigens have been modified to promote targeting to particular accessory cells (eg, targeting of complement receptors48 ) or intracellular compartments within accessory cells (eg, ER targeting49 ), synthetic or microbial TLR ligands have been used (reviewed by Celis et al50 ), and cytokines, mAbs, and other engineered immunomodulators have been incorporated into vaccines with some success. Many of the strategies that have been used to enhance responses to tumor antigens represent attempts to substitute for immune response-enhancing activities that are supplied by helper T cells during physiologic responses to exogenous antigens. Increasingly, it is clear that effective immune responses are initiated in lymphoid organs with spatial relationships that are optimal, that distinct types of cells must participate in an intricate dialogue mediated by cell surface and soluble proteins, that relative strengths of enhancing and inhibitory signals are important, and that the timing of signaling between cells is critical. Thus, effective substitution for T-cell help might require administration of the correct cocktail of immune modulators in the appropriate ratios in the right site in an exact temporal sequence. We suggest that bystander enhancement of responses to weak antigens via stimulation of exogenous antigen-reactive (presumably) CD4 helper T cells represents an attractive and simpler alternative strategy that may obviate the need to define and replicate all of the critical variables.

The hypothesis that incorporation of helper antigens into tumor vaccines might improve efficacy is not novel. Indeed, KLH is already used as a component of an idiotype protein-based regimen that induces antibodies that are reactive with the clonally restricted antigen receptors (surface immunoglobulin) that are expressed by malignant B cells51 and that has already been demonstrated to be active in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.52 Most attempts to incorporate helper antigens into tumor vaccines that stimulate cytotoxic CD8 T cells have involved creation of expression vectors that encode tumor antigens fused in-frame to cDNA encoding helper determinants. Administration of fusion constructs with this structure results in the production of tumor antigen- and helper antigen-derived epitopes in the same cell in equimolar amounts, a circumstance that can promote competition between tumor and helper antigen-derived peptides for MHC class I– and class II–binding sites. Some have addressed this theoretical and practical problem by truncating the helper antigen portion of the fusion construct to reduce numbers of competing peptides corresponding to nondominant epitopes, or by deliberately engineering the construct so that it does not encode predicted MHC class I–binding peptides derived from the helper antigen.53 Although this approach may be practical in experiments involving congenic mice, it could not be easily implemented in humans where a variety of MHC molecules are relevant and the identity and relative immunodominance of antigenic peptides from both tumor and helper antigens are unknown. To circumvent MHC restrictions, some investigators have described universal helper epitopes, which bind to a variety of MHC haplotypes.54

Our initial attempts to augment immune responses to TCR proteins by coadministering equivalent amounts of plasmid encoding highly immunogenic full-length foreign antigen on the same gold particles failed, suggesting that relative immunodominance and competition between tumor antigen- and helper antigen–derived peptides are a significant issue. We were able to circumvent this problem by reducing the amount of plasmid-encoding helper antigen to levels that were just sufficient to induce cell-mediated responses. Interestingly, these limiting plasmid doses were not sufficient to induce humoral responses to helper antigen. In addition, the tumor antigen–enhancing effects of helper antigen were optimal when plasmid DNA encoding both tumor and helper antigens were delivered into the same cutaneous site on the same particles, resulting in the cotransfection of skin cells. This result strongly suggests that both tumor and helper antigen must be produced in the same cell (presumably a dendritic cell) for maximal effect.

It will be important to determine whether the simple methodology we describe will be broadly applicable. To date, we have determined that the low-dose helper effect is not limited to β-gal but can also be observed with fragment C of tetanus toxin. Initial results also suggest that enhanced immune responses to murine melanoma occur when a gp100-encoding plasmid is codelivered with low doses of a plasmid encoding a helper antigen. Moving our observation toward the clinic will be challenging. Plasmid DNA vaccines have not been highly efficacious in primates, and it is not at all certain that gene gun immunization will ever be widely used in humans. Thus, our future efforts will be directed toward developing alternative methods that allow titered expression of self and exogenous antigens in the same cells, and that can be easily implemented in humans. With these caveats, we are optimistic that the simple approach described here will ultimately be useful in patients with, or who are at risk for, cancer or chronic infections.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Elke S. Bergmann-Leitner (Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD) for statistical evaluation of the data.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and Center for Cancer Research.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: W.W.L. designed and performed experiments, analyzed and discussed data, and wrote the paper; M.C.B. and T.L.B. performed experiments; M.C.L. cloned plasmids and performed experiments; P.J.Y. cloned the TCR vaccine; and M.C.U. initiated the study, analyzed and discussed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mark C. Udey, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10/12N238, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: udey@helix.nih.gov.