To the editor:

Mechanisms for neutropenia are diverse and incompletely understood. Copper is an essential mineral that is absorbed in the intestine, bound to a carrier protein, transported to the liver, and then stored. Approximately 95% of copper found in the blood is bound to ceruloplasmin. Animal models have demonstrated that profound nutritional copper deficiency results in severe neutropenia due to granulopoeisis maturation arrest.1 In humans, copper deficiency has been reported almost always in patients with chronic intestinal dysfunction, often including gastrostomy, resulting in severe copper malabsorption and frequently anemia, neutropenia and dysmyelopoietic features.2 It is noteworthy that, copper deficiency related neutropenia can be related to anti–neutrophil antibodies.3 Copper deficiency may worsen anemia in patients with kidney failure4 ; however, it has never been observed in relation to nephrotic proteinuria responsible for urinary ceruloplasmin loss.

The patient was born at 37 weeks gestational age. General edema was present at birth for which congenital nephrotic syndrome (CNF) of the Finnish type was suspected. Renal biopsy showed normal glomeruli and dilated tubuli, and genetic analysis revealed a composite heterozygote mutation in the NPHS1 gene (c.802C>T; exon 7 and c.2212 + 2delTG; exon 16) coding for nephrin. Massive proteinuria is generally seen in CNF, requiring high-dose intravenous albumin and immunoglobulin supplementation. In our patient proteinuria was exceptionally high (∼150 g/L) and the patient required higher doses of albumin (10 g/kg) to keep serum albumin level greater than 20 g/L.

At the age of 2 months, anemia (Hb 6.5 gr/dL) and neutropenia (280/mm3) were detected, while platelet and lymphocyte count remained normal. There was no clinical or biologic evidence for infection. An infectious work-up, including EBV, CMV, and parvovirus B19 polymerase chain reaction was negative. Anti–neutrophil antibodies were negative. Bone marrow biopsy showed a moderate leukocyte maturation arrest mainly at the myelocyte level and rare megakaryocytes. We measured total copper serum level that was low (3.5 μM; normal range, 12-25 μM); ceruloplasmin level was decreased (0.07 g/L) due to urinary loss of the 135-kDa ceruloplasmin.

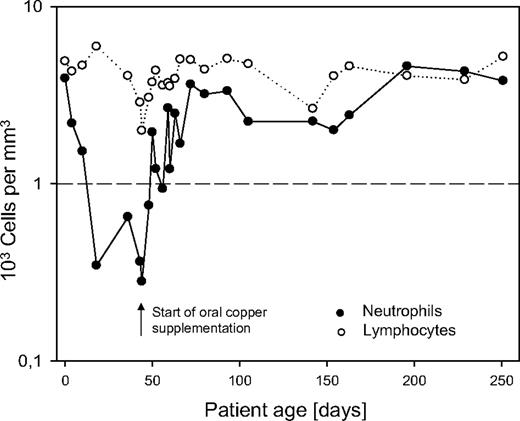

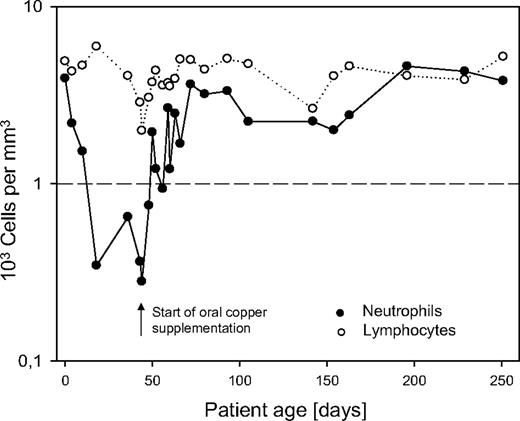

Oral supplementation of copper sulfate was started at 10 mg per day while white blood cell count and copper serum levels were monitored closely. During copper supplementation, neutrophil count increased and reached an almost normal level of 752/mm3 (ANC) after 8 days, completely normalized 1 week later, and remained stable (Figure 1). Total copper serum level remained low, as 95% of total copper is bound to ceruloplasmin. However, increase of free copper was correlated to a normalization of neutrophil count, whereas anemia persisted. Anemia refractory to erythopoetin (until 600 U/kg), iron, and vitamin B12 suplementation persisted and was later explained by urinary loss of transferrin and transcobolamin. This second aspect in relation to extremely high proteinuria is reported elsewhere.5

In conclusion, ceruloplasmin loss due to massive proteinuria may cause copper depletion involved in the pathogenesis of neutropenia. This pathophysiologic mechanism for neutropenia has not yet been reported in humans. Oral copper supplementation led to rapid increase of neutrophil count. Therefore, it should be considered rapidly to reduce the risk for infectious complications in patients with CNF.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tim Ulinski, MD, PhD, Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Armand Trousseau Hospital, 26 Avenue du Docteur Arnold Netter, 75012 Paris, France; e-mail: tim.ulinski@trs.aphp.fr.