Although rituximab is a key molecular targeting drug for CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas, resistance to rituximab has recently been recognized as a considerable problem. Here, we report that a CD20-negative phenotypic change after chemotherapies with rituximab occurs in a certain number of CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma patients. For 5 years, 124 patients with B-cell malignancies were treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapies in Nagoya University Hospital. Relapse or progression was confirmed in 36 patients (29.0%), and a rebiopsy was performed in 19 patients. Of those 19, 5 (26.3%; diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL], 3 cases; DLBCL transformed from follicular lymphoma, 2 cases) indicated CD20 protein-negative transformation. Despite salvage chemotherapies without rituximab, all 5 patients died within 1 year of the CD20-negative transformation. Quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showed that CD20 mRNA expression was significantly lower in CD20-negative cells than in CD20-positive cells obtained from the same patient. Interestingly, when CD20-negative cells were treated with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in vitro, the expression of CD20 mRNA was stimulated within 3 days, resulting in the restoration of both cell surface expression of the CD20 protein and rituximab sensitivity. These findings suggest that some epigenetic mechanisms may be partly related to the down-regulation of CD20 expression after rituximab treatment.

Introduction

Rituximab is a murine/human chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that has become a key molecular targeting drug for CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas.1,2 Many favorable results using combination chemotherapy with rituximab for both CD20-positive de novo and relapsed low-grade and aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma have been reported in recent years.3,,,–7 In Japan, rituximab has also been used since September 2001 for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), indolent lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). In addition, since September 2003 in Japan, indications for using rituximab were expanded to include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), further demonstrating the significant effectiveness of rituximab for B-cell lymphoma compared with conventional chemotherapies without rituximab.8

Although combination chemotherapies with rituximab have provided significantly favorable results for CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma patients, acquired resistance to rituximab has become a considerable problem. Several mechanisms of resistance were predicted as reported previously, including loss of CD20 expression, inhibition of antibody binding, antibody metabolism, expression of complement inhibitors such as CD55/CD59, and membrane/lipid raft abnormality (reviewed by Smith et al9 ),10,,,,,,,,–19 but the clinical significance of those mechanisms has remained unclear. In the last 5 years, a CD20-negative phenotypic change in CD20-positive lymphomas after rituximab treatment has been reported by several groups,16,20,,,,,,,,,,–31 indicating that this phenomenon after the use of rituximab may not be rare. Although these reports contain important information from clinical experiences, the frequency of occurrence and detailed molecular biologic information about the CD20-negative phenotype remain to be elucidated.

Very recently, we reported a CD20-negative DLBCL case that had transformed from CD20-positive FL after repeated treatment with rituximab. We established an RRBL1 cell line from this patient,32 and the mechanisms of the CD20-negative change were analyzed in these cells. CD20 mRNA expression was significantly lower than in CD20-positive cells, resulting in a loss of CD20 protein expression as detected by flow cytometry (FCM), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and immunoblotting (IB). Interestingly, trichostatin A (TSA), a histone deacetylase inhibitor, was able to successfully stimulate CD20 expression, suggesting that some epigenetic mechanisms may have repressed the expression. Thus, an accumulation of detailed clinical and molecular biologic features is required to demonstrate the significance of CD20-negative phenotypic changes after rituximab treatment.

In the last 5 years, 124 patients with CD20-positive B-cell malignancies received chemotherapy with rituximab at Nagoya University Hospital, 36 (29.0%) of whom showed relapse/progression. Among these 36 patients, CD20 protein-negative or -decreased phenotypic changes were confirmed in 5 cases concomitant with disease progression. Here, we describe the occurrence rate of CD20-negative transformation after rituximab treatment, as well as the molecular background of the CD20 protein-negative phenotype in cells from those patients.

Methods

Patients

Between February 1988 and November 2006 in Nagoya University Hospital, all 124 patients in this analysis were initially diagnosed with CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas (Table 1) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.33 All patients were treated with combination chemotherapy with rituximab from September 2001 to December 2006. The median age of the patients was 58 years (range, 16-84 years) at the time of initial rituximab administration. Three patients had received rituximab before September 2001 because of their participation in a previous clinical study. The most recent follow-up date was July 31, 2007, and disease status factors such as relapse, recurrence, and progression were determined by clinical findings and diagnostic imaging using x-ray, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). Resampling of tumors at the time of relapse/progression and pathologic analysis of 19 patients was performed. The patients' responses to chemotherapies were evaluated using the International Working Group criteria.34

Confirmation of CD20 protein expression by IHC and FCM analyses

These studies were conducted with institutional review board approval from the Nagoya University School of Medicine. After obtaining appropriate informed consent from each patient, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, tumor specimens were harvested from lymph nodes, bone marrow, peripheral blood, or spinal fluid. CD20 protein expression was demonstrated by IHC and/or FCM as indicated previously.32,35 Briefly, we used mouse anti-CD20 (L26; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), anti-CD10 (Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom), and anti-CD79a monoclonal antibodies (Dako) for IHC, and mouse anti-CD20 (B2E9; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and anti-CD19 (HD37; Dako) monoclonal antibodies for FCM. The CD79a antigen is a pan–B-cell marker that forms a B-cell receptor (BCR) protein complex. The percentages of negative and positive cells from FCM were determined from the data using an isotypic control antibody (mouse IgG1; Beckman Coulter).

Sequence analysis of the MS4A1 (CD20) gene

Genomic DNA from tumor cells was extracted with a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and used for further polymerase chain reactions (PCRs). When sufficient tumor cells could not be obtained at diagnosis, genomic DNA from paraffin sections was extracted using the MagneSil Genomic, Fixed Tissue System (Promega, Madison, WI). Genomic DNA PCR was performed using AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to acquire fragments of the coding sequences of exons 3 to 8 of the MS4A1 (CD20) gene. The following primers were designed from the appropriate intron sequences to achieve the coding sequences: exon 3-upper (U), 5′-GCT CTT CCT AAA CAA CCC CT-3′; exon 3-lower (L), 5′-CAT GGG ATG GAA GGC AAC TGA C-3′; exon 4-U, 5′-TGC TGC CTC TGT TCT CTC CC-3′; exon 4-L, 5′-CTG CAC CAT TTC CCA AAT GGC T-3′; exon 5-U, 5′-CTC CAT CTC CCC CAC CTC TC-3′; exon 5-L, 5′-GGT ACT TCT CTG ACA TGT GGG A-3′; exon 6-U, 5′-TGG AAT TCC CTC CCA GAT TAT G-3′; exon 6-L, 5′-CCT GGA GAG AAA TCC AAT CTC A-3′; exon 7-U, 5′-GTC TCC TGT ACT AGC AGT TC-3′; exon 7-L, GGC TAC TAC TTA CAG ATT TGG G-3′; exon 8-U, 5′-TGG TCA ATG TCT GCT GCC CT-3′; and exon 8-L, 5′-GCG TAT GTG CAG AGT ACC TCA AG-3′. Amplified fragments were cloned into a pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega) and were sequenced using a DNA auto sequencer (ABI PRISM 310; Applied Biosystems). PCR fragments that contained each exon sequence were cloned into the pGEM-T vector, and at least 10 clones were sequenced. If a mutation was observed in 2 different clones, we verified that the sequence reflected a mutation in the tumor rather than a PCR error.

RNA extraction and reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction

A blood RNA extraction kit (QIAGEN) was used to isolate total RNA from tumor cells. cDNA was prepared as reported previously.36 For reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analyses of CD10, CD19, CD20, and β-actin, the following primers were designed: CD10-U, 5′-TTG TCC TGC TCC TCA CCA TC-3′; CD10-L, 5′-GTT CTC CAC CTC TGC TAT CA-3′; CD19-U, 5′-GAA GAG GGA GAT AAC GCT GT-3′; CD19-L, 5′-CTG CCC TCC ACA TTG ACT G-3′; CD20-U, 5′-ATG AAA GGC CCT ATT GCT ATG-3′; CD20-L, 5′-GCT GGT TCA CAG TTG TAT ATG-3′; β-actin-U, 5′-TCA CTC AAG ATC CTC A-3′; and β-actin-L, 5′-TTC GTG GAT GCC ACA GGA C-3′. Semiquantitative RT-PCR with AmpliTaq Gold was performed as described previously.32 Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out using TaqMan PCR (ABI PRISM 7000; Applied Biosystems) as previously described.32,36

Immunoblot analysis

Cells (∼5 × 105) were lysed in 100 μL lysis buffer (50 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane [Tris]-HCl [pH 8.0], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ester)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid [EGTA], 5 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 300 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and a Complete Mini protease inhibitor tablet [Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN]). After centrifugation at 10 000g for 10 minutes, the supernatants were placed in new tubes and 100 μL of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer was added. After boiling for 5 minutes, samples were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Immunoblotting was carried out as described previously32,37 using goat polyclonal anti-CD20 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and rabbit polyclonal anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Treatment of RRBL1 cells and primary lymphoma cells with the epigenetic drug 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine

RRBL132 and primary lymphoma cells (5 × 105) were cultured in 6-well dishes in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 hours with or without 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at a final concentration of 100 mM. The cells were then washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, and incubated for more than 2 days in the same medium without 5-Aza. Cells were harvested and used for total RNA and protein extraction.

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay in vitro

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity was analyzed by an in vitro chromium-51 (51Cr) release assay. Target cells (RRBL1, Daudi, DHL10) were cultured in appropriate medium supplemented with 10% to 20% FBS. Each cell line (2.0 × 105 cells) was labeled with 100 μCI (3.7 MBq) of Na251CrO4 (PerkinElmer Japan, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C for 1 hour. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), which were obtained from a healthy donor, were prepared as effector cells of the cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay. 51Cr-labeled target cells were divided into aliquots in 96-well plates (104 cells/well). Effector PBMC cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were then added to each well in the presence or absence of rituximab (0 to 31.25 μg/mL) and incubated for 4 hours at 37°C. Supernatants were obtained after a brief centrifugation and measured on a γ-ray counter (PerkinElmer). 51Cr-labeled target cells without antibodies were lysed completely by NP-40 (2% final concentration) and used as a positive control (the maximal 51Cr release). The percentage of lysed cells was calculated using the following formula: % cell lysis = [(experimental release (cpm) − background (cpm)/(maximal release (cpm) − background (cpm))] × 100%, where cpm indicates counts per minute.

Results

CD20-negative phenotypic change after treatment with rituximab

A total of 124 patients with CD20-positive B-cell malignancies were treated with rituximab-combined chemotherapy from September 2001 to December 2006 (Table 1). All patients were diagnosed with CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas by IHC and/or FCM analyses using their tumor tissue specimens. Thirty-six patients (29.0%) showed relapse and progression (response; relapse/progression of disease [RD/PD] in Table 1) of their disease after or during chemotherapies with rituximab. Tumor cells from 19 of these 36 patients (52.8%) were resampled at the time of RD/PD, and CD20 protein expression was analyzed by IHC and/or FCM. CD20 protein expression was not detected or was significantly decreased in 5 patients (DLBCL, 3 patients; FL, 2 patients). Therefore, in 26.3% of patients whose tumor cells were resampled at the time of RD/PD, a CD20-negative phenotypic transformation after rituximab treatment was observed.

Clinical and laboratory features of patients with a CD20-negative phenotypic change

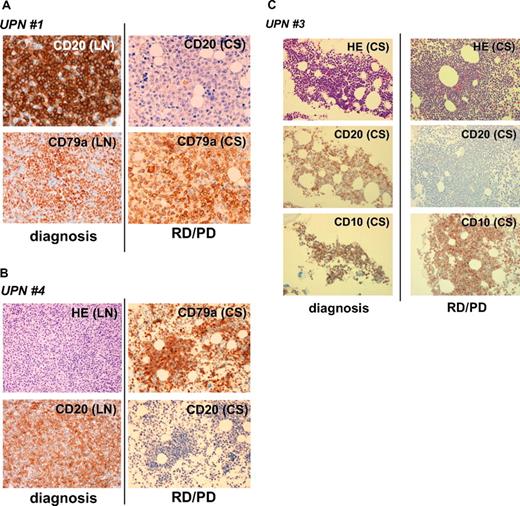

The clinical features of the 5 patients with a CD20-negative phenotypic change after rituximab treatment are shown in Table 2. Initially, 3 patients were diagnosed with DLBCL and 2 patients were diagnosed with FL. They were treated with chemotherapy with rituximab (375 mg/m2) repeatedly until a CD20-negative phenotypic change was observed. Four to 14 cycles of rituximab were administered. These 5 patients showed relapse or progression from 2 to 81 months after their first treatment with rituximab. Histologic transformation from FL was observed in 2 patients, resulting in all 5 patients being diagnosed histologically as DLBCL at the time of RD/PD. Tumor cell infiltration into the bone marrow was observed in all 5 patients. A CD20 protein-negative phenotype was confirmed by IHC (Figure 1) and FCM in all 5 cases. In 3 patients, mRNA from tumor tissues was available, and CD20 mRNA expression was faintly observed using RT-PCR. Although all 5 patients received salvage chemotherapy without rituximab, they all died from disease progression within 11 months of the confirmation of CD20-negative transformation. The clinical outcomes of these patients who showed RD/PD after treatment with rituximab-containing chemotherapy are shown in Table 3. The 5 patients with CD20-negative RD/PD tended to have a shorter survival time than with CD20-positive RD/PD (100% vs 35.7% died). However, statistical significance could not be determined because of the variable disease status of each patient, including different backgrounds, salvage chemotherapies, and other factors. More patients must be studied to further analyze this apparent trend.

CD20 protein–negative phenotypic changes in CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma patients after treatment with rituximab-containing chemotherapy. Tissue samples (LN, lymph nodes; CS, bone marrow clot section) obtained from UPNs 1 (A), 4 (B), and 3 (C) in Table 2 were analyzed by IHC using anti-CD20, anti-CD79a, and anti-CD10 antibodies. Anti-CD79a antibody was used for detection of B cells. Note that CD20 was positive at the time of initial diagnosis in these patients, and that the CD20-negative phenotypic change was observed during the relapse/progression period. Original magnifications, ×400 (A) and ×200 (B,C) (Olympus BX51TF microscope, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan, and Nikon DS-Fi1 camera, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). HE indicates hematoxylin and eosin staining; and RD/PD, relapse/progression of disease.

CD20 protein–negative phenotypic changes in CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma patients after treatment with rituximab-containing chemotherapy. Tissue samples (LN, lymph nodes; CS, bone marrow clot section) obtained from UPNs 1 (A), 4 (B), and 3 (C) in Table 2 were analyzed by IHC using anti-CD20, anti-CD79a, and anti-CD10 antibodies. Anti-CD79a antibody was used for detection of B cells. Note that CD20 was positive at the time of initial diagnosis in these patients, and that the CD20-negative phenotypic change was observed during the relapse/progression period. Original magnifications, ×400 (A) and ×200 (B,C) (Olympus BX51TF microscope, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan, and Nikon DS-Fi1 camera, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). HE indicates hematoxylin and eosin staining; and RD/PD, relapse/progression of disease.

Genetic abnormalities in the CD20 gene

Genomic DNA mutations in the coding sequence (CDS) of the CD20 gene, also known as the MS4A1 gene, were also analyzed in the 5 patients. If the mutations were located in specific domains that are recognized by anti-CD20 antibodies including rituximab, those mutations might be related to resistance to rituximab and/or the CD20-negative phenotype. As indicated in Table 2, the change in serine 97 to phenylalanine (S97F; TCC → TTC) in unique patient number (UPN) 1 and valine 247 to isoleucine (V247I; GTT → ATT) in UPN 2 were confirmed in 2 clones each of 16 and 10 clones, respectively. In the other 3 cases, no genetic mutations in the MS4A1 CDS were detected. Chromosomal analysis by G-banding was also performed using tumor cells obtained from each patient in both the initial diagnosis (CD20-positive) and at the time of RD/PD (CD20-negative; Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Chromosomal abnormalities involving 11q12 containing the MS4A1 gene were not observed.

Alteration of CD20 protein and mRNA expression levels after treatment with rituximab

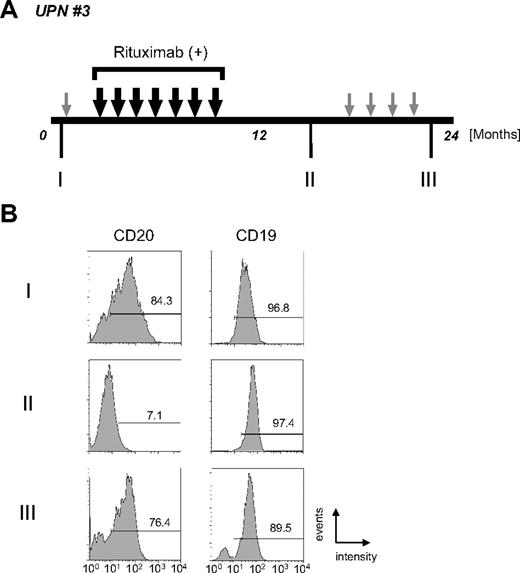

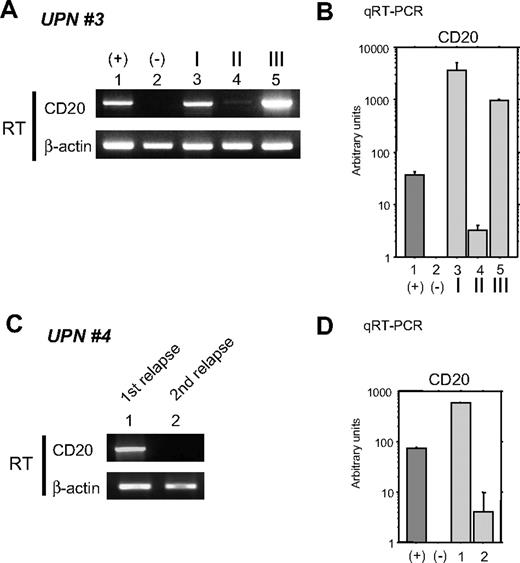

As shown in Figure 1, CD20 protein expression by IHC analysis is altered after chemotherapy with rituximab. The clinical course of UPN 3 is depicted briefly in Figure 2A. FCM analyses using appropriate lymphoma tissues from lymph nodes, peripheral blood, bone marrow, and/or cerebral fluid were performed at admission (I), upon relapse after treatment with rituximab-containing combination chemotherapy (II), and at the end stage of disease after salvage chemotherapy without rituximab (III). The results of FCM analysis using peripheral blood, which contains lymphoma cells, are shown in Figure 2B. Interestingly, CD20 protein expression recognized by FCM analysis was significantly diminished at stage II, but was reversed at stage III. At stage II, CD20-negative lymphoma cell infiltration into the cerebral fluid was also confirmed by FCM analysis (data not shown). On the other hand, CD19 expression, which is also present on B-cell lymphoma cells, was detected constantly throughout the clinical course (Figure 2B right column). Semiquantitative RT-PCR (Figure 3A) and quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 3B) show that the mRNA expression level of CD20 was significantly altered in each stage. CD20 mRNA expression was faintly observed at stage II (Figure 3B column 4) when CD20 protein expression was barely detectable with FCM (Figure 2B) and IHC (Figure 1C). In UPN 4, CD20 mRNA expression levels were determined by RT-PCR using tumor samples obtained before and after treatment with rituximab-containing chemotherapy (Figure 3C,D). Similar to UPN 3, CD20 mRNA expression was significantly decreased, and no protein expression was detected with IHC (Figure 1B). These findings suggest that CD20 protein expression is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level, and that the expression may be down-regulated in patients who show CD20-negative transformation after treatment with rituximab.

Alteration of CD20 protein expression on B-cell lymphoma cells during disease progression. (A) The clinical course of UPN 3 is depicted briefly. Large black arrows and smaller gray arrows indicate one course of combination chemotherapy with or without rituximab, respectively. Rituximab (375 mg/m2 each) was administered 7 times. During the patient's 24-month clinical course, tumor cells were harvested at stages I, II, and III from lymph nodes, bone marrow, peripheral blood, and/or cerebral fluid. (B) FCM analysis using anti-CD20 and anti-CD19 antibodies was carried out using tumor cells from peripheral blood. Positive cells are shown in the black lines, and the percentage of positive cells is shown. Note that CD20 expression was observed at the initial diagnosis (I, 84.3%), and that the expression then diminished after treatment with chemotherapy with rituximab (II, 7.1%). Interestingly, CD20 protein expression was observed again at the terminal stage after several chemotherapy treatments without rituximab (III, 76.4%). On the other hand, CD19 expression level was stable throughout the clinical course.

Alteration of CD20 protein expression on B-cell lymphoma cells during disease progression. (A) The clinical course of UPN 3 is depicted briefly. Large black arrows and smaller gray arrows indicate one course of combination chemotherapy with or without rituximab, respectively. Rituximab (375 mg/m2 each) was administered 7 times. During the patient's 24-month clinical course, tumor cells were harvested at stages I, II, and III from lymph nodes, bone marrow, peripheral blood, and/or cerebral fluid. (B) FCM analysis using anti-CD20 and anti-CD19 antibodies was carried out using tumor cells from peripheral blood. Positive cells are shown in the black lines, and the percentage of positive cells is shown. Note that CD20 expression was observed at the initial diagnosis (I, 84.3%), and that the expression then diminished after treatment with chemotherapy with rituximab (II, 7.1%). Interestingly, CD20 protein expression was observed again at the terminal stage after several chemotherapy treatments without rituximab (III, 76.4%). On the other hand, CD19 expression level was stable throughout the clinical course.

Alteration of CD20 mRNA expression in B-cell lymphoma cells during the clinical course. (A) RT-PCR (RT) was performed using total RNA from the same tumor cells as in Figure 2B (UPN 3 in Table 2). As positive and negative controls, total RNA from Raji and 293T cells was used (lanes 1 and 2), respectively. I, II, and III (lanes 3-5) correspond to the clinical stages depicted in Figure 2A. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the same RNA as in panel A. Arbitrary units of CD20 mRNA expression are indicated in the vertical axis. Note that faint expression of CD20 mRNA could be seen at stage II (column 4) despite a loss of CD20 surface protein expression as shown in Figure 2B. (C) CD20 mRNA expression in the lymphoma cells of UPN 4 (Table 2) was also analyzed. Tumor cells were derived from cerebral fluid at the first relapse after chemotherapy without rituximab (lane 1). Although complete remission was obtained after using rituximab-containing salvage chemotherapy, a second relapse occurred. Tumor cells were once again harvested from this patient's cerebral fluid and analyzed (lane 2). (D) Quantitative RT-PCR was also performed using the same RNA as in (C). Note that CD20 mRNA expression was significantly diminished but could still be observed. In these cells, CD20 protein expression was undetectable using FCM or IHC as indicated in Table 2. Positive and negative controls derived from Raji and 293T cells are indicated by + and −, respectively.

Alteration of CD20 mRNA expression in B-cell lymphoma cells during the clinical course. (A) RT-PCR (RT) was performed using total RNA from the same tumor cells as in Figure 2B (UPN 3 in Table 2). As positive and negative controls, total RNA from Raji and 293T cells was used (lanes 1 and 2), respectively. I, II, and III (lanes 3-5) correspond to the clinical stages depicted in Figure 2A. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the same RNA as in panel A. Arbitrary units of CD20 mRNA expression are indicated in the vertical axis. Note that faint expression of CD20 mRNA could be seen at stage II (column 4) despite a loss of CD20 surface protein expression as shown in Figure 2B. (C) CD20 mRNA expression in the lymphoma cells of UPN 4 (Table 2) was also analyzed. Tumor cells were derived from cerebral fluid at the first relapse after chemotherapy without rituximab (lane 1). Although complete remission was obtained after using rituximab-containing salvage chemotherapy, a second relapse occurred. Tumor cells were once again harvested from this patient's cerebral fluid and analyzed (lane 2). (D) Quantitative RT-PCR was also performed using the same RNA as in (C). Note that CD20 mRNA expression was significantly diminished but could still be observed. In these cells, CD20 protein expression was undetectable using FCM or IHC as indicated in Table 2. Positive and negative controls derived from Raji and 293T cells are indicated by + and −, respectively.

Epigenetic regulation of CD20 gene expression after treatment with rituximab

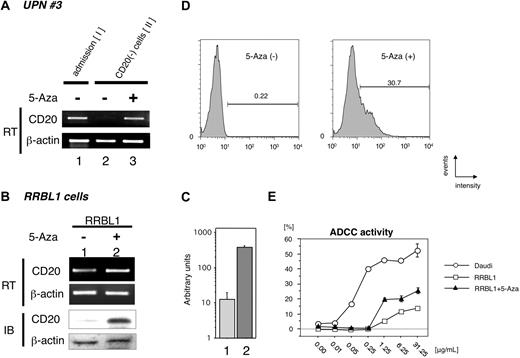

These findings suggest that CD20 expression is partly epigenetically regulated by factors such as rituximab treatment surrounding tumor cells, or that CD20-negative tumor cells are able to grow selectively during rituximab treatment. If the CD20-negative B cells still possess the capability to express CD20 protein, we hypothesized that some epigenetic drugs38,39 may be able to stimulate the CD20 transcription. First, we examined CD20 transcription after treatment with 5-Aza using primary tumor cells derived from cerebral fluid of UPN 3 at stage II in Figure 2A, which showed a CD20-negative phenotype. As a CD20-positive control, lymphoma cells at the initial diagnosis from the same patient were used (Figure 4A lane 1). After treatment with 5-Aza in vitro, significant stimulation of CD20 expression was observed (Figure 4 lane 3).

Restoration of CD20 mRNA and protein expression by treatment with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-Aza. (A) Primary B-cell lymphoma cells, which showed a CD20 protein-negative phenotype from UPN 3, were incubated with or without 5-Aza. Total RNA was prepared, and semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed. Restoration of CD20 mRNA expression after treatment with 5-Aza was observed in lane 3. As a positive control, tumor cells obtained at the initial diagnosis of that same patient were used in lane 1. (B) The CD20 protein-negative B-cell lymphoma cell line RRBL1,32 which was derived from UPN 5 in Table 2, was incubated in culture medium with or without 5-Aza. After preparation of total RNA and whole-cell lysates from these cells, semiquantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting (IB) were performed. Up-regulation of CD20 mRNA and protein expression was observed as shown in lane 2. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the same mRNA as in (B). We observed an up-regulation of more than 10-fold in CD20 mRNA after treatment with 5-Aza (column 2). (D) RRBL1 cells were treated with 5-Aza under the same conditions as in (B), and FCM analysis using anti-CD20 antibody was performed. After treatment with 5-Aza, 30.7% of RRBL1 cells showed a CD20-positive phenotype. Positive cells are shown with black lines, and the percentage of positive cells is also shown. (E) In vitro ADCC analysis using the 51Cr-release assay. Cells from the CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma/leukemia cell lines Daudi and RRBL1 treated with or without 5-Aza were used for this assay. In Daudi cells (○), but not in RRBL1 cells (□), cytotoxic activity was observed in the presence of rituximab in a dose-dependent manner. Partial restoration of rituximab sensitivity in RRBL1 cells was observed after treatment with 5-Aza (▲). Error bars indicate plus or minus 1 standard deviation.

Restoration of CD20 mRNA and protein expression by treatment with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-Aza. (A) Primary B-cell lymphoma cells, which showed a CD20 protein-negative phenotype from UPN 3, were incubated with or without 5-Aza. Total RNA was prepared, and semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed. Restoration of CD20 mRNA expression after treatment with 5-Aza was observed in lane 3. As a positive control, tumor cells obtained at the initial diagnosis of that same patient were used in lane 1. (B) The CD20 protein-negative B-cell lymphoma cell line RRBL1,32 which was derived from UPN 5 in Table 2, was incubated in culture medium with or without 5-Aza. After preparation of total RNA and whole-cell lysates from these cells, semiquantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting (IB) were performed. Up-regulation of CD20 mRNA and protein expression was observed as shown in lane 2. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the same mRNA as in (B). We observed an up-regulation of more than 10-fold in CD20 mRNA after treatment with 5-Aza (column 2). (D) RRBL1 cells were treated with 5-Aza under the same conditions as in (B), and FCM analysis using anti-CD20 antibody was performed. After treatment with 5-Aza, 30.7% of RRBL1 cells showed a CD20-positive phenotype. Positive cells are shown with black lines, and the percentage of positive cells is also shown. (E) In vitro ADCC analysis using the 51Cr-release assay. Cells from the CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma/leukemia cell lines Daudi and RRBL1 treated with or without 5-Aza were used for this assay. In Daudi cells (○), but not in RRBL1 cells (□), cytotoxic activity was observed in the presence of rituximab in a dose-dependent manner. Partial restoration of rituximab sensitivity in RRBL1 cells was observed after treatment with 5-Aza (▲). Error bars indicate plus or minus 1 standard deviation.

Previously, we established the CD20-negative B-cell lymphoma cell line RRBL1,32 which was derived from CD20-negative tumor cells in peripheral blood from a patient (UPN 5 in Table 2). Next, we performed the same assay using these cells (Figure 4B), and we were able to show up-regulation of CD20 mRNA expression (Figure 4B,C). CD20 protein expression induction was also confirmed by immunoblotting (Figures 4B, IB). Thus, these data, showing that CD20 expression could be stimulated within a few days, suggested that CD20 expression is down-regulated by epigenetic mechanisms.

Restoration of rituximab sensitivity in CD20-negative cells after treatment with 5-Aza in vitro

From these findings, we hypothesized that rituximab sensitivity would be restored if we could stimulate CD20 protein expression on the surface of CD20-negative transformed lymphoma cells. To test this hypothesis, we performed FCM analysis and an in vitro ADCC assay using RRBL1 cells with or without 5-Aza treatment. As shown in Figure 4D, CD20 protein expression was induced on the surface of 30.7% of RRBL1 cells after treatment with 5-Aza. Using these cells with or without 5-Aza treatment, an in vitro 51Cr-release assay was performed to confirm ADCC activity induced by rituximab (Figure 4E). Daudi cells were used as CD20-positive rituximab-sensitive control cells. In the presence of rituximab, cell death was observed in a dose-dependent manner in Daudi cells. In contrast, the percentage of RRBL1 cells undergoing cell death was significantly lower despite the high concentration of rituximab. RRBL1 cells treated with 5-Aza showed partial rituximab sensitivity compared with RRBL1 cells not treated with 5-Aza. These experiments were done in triplicate and repeated at least 3 times, with similar results. These data suggest that CD20 expression and rituximab sensitivity could be restored in some cases using epigenetic drug treatment even when CD20-negative transformation results from rituximab treatment. Further experiments using patients' primary samples and an in vivo system will be required to further explore this idea.

Discussion

Rituximab is a clinically important antitumor monoclonal antibody targeting the CD20 surface antigen expressed on B-cell malignancies. However, its effectiveness is sometimes unsatisfactory since a significant percentage of patients treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy showed relapse or progression.3,6,40 In this report, we also estimated that RD/PD after treatment with rituximab was observed in almost 30% of B-cell lymphoma patients after treatment with combination chemotherapies with rituximab. Importantly, not all patients who show RD/PD demonstrate resistance to rituximab. In fact, some patients were sensitive to retreatment with rituximab-containing salvage chemotherapies (data not shown). We may need to define “rituximab resistance” more carefully by monitoring each patient's clinical course.

A CD20-negative phenotypic change was observed in 26.3% of patients for whom tumor resampling (rebiopsy) was carried out (Table 1). We generally perform rebiopsies when tumor progression becomes very aggressive or when the manner of tumor expansion significantly changes during clinical observation. If we had carried out resampling on every RD/PD patient, the percentage of patients with CD20-negative transformations may have been much lower. Thus, examination of more patients will be critical. One important observation about the CD20-negative phenotypic change is that all 5 patients died from their disease progression within 1 year after showing a CD20-negative transformation (Tables 2,3). This observation may indicate that a loss of CD20 expression is partly related to poor prognosis. In our study, however, patients' backgrounds varied (eg, age, sex, pathologic findings, chemotherapy regimens, and organ function). A larger patient sample is warranted to determine the significance of the loss of CD20 expression.

It is noteworthy that CD20 mRNA expression was confirmed by RT-PCR even in those tumor cells that showed a CD20 protein-negative phenotype using IHC, FCM, and immunoblotting (Figure 3). In one case (Figure 3, UPN 3), expression of CD20 mRNA and protein were observed again after salvage chemotherapy without rituximab. Clonal evolution may be one reason for the alteration of CD20 mRNA and protein expression patterns in the same patient either with or without rituximab. However, our finding of the restoration of CD20 mRNA and protein expression within 3 days after treatment with 5-Aza (Figure 4) may instead support the idea that expression is regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, rather than by the alteration of several tumor clones.

We cannot exclude the possibility that genetic alteration in tumor cells that affects the expression of transcription factors PU.1, Pip, and Oct2, which are thought to be critical for MS4A1 (CD20) gene expression,41 may contribute to the aberrant CD20 transcriptional regulation. We analyzed the methylation status of cytosine guanine dinucleotides (CpGs) in CD20 promoters almost 1000 bp upstream from the transcription start site to determine the mechanism of transcription up-regulation by 5-Aza treatment. Interestingly, CpG islands do not exist in the promoter site, and only 4 CG sequences can be observed in that region. Methylation of the 4 CG sites was not observed in the tumor cells from UPN 5 and RRBL1 cells using bisulfite sequencing (data not shown). Mechanisms other than DNA methylation of the CD20 promoter may also be responsible for aberrant transcription down-regulation.

It is also possible that down-regulation of CD20 protein via such mechanisms as microRNA, protein folding, exportation, or glycosylation may occur. A recent report suggested the possibility that both CD20 gene expression (at the pre- and posttranscriptional level) and protein down-regulation are related to the loss of CD20 protein expression after treatment with rituximab in vitro, resulting in rituximab resistance.10 In addition, down-regulation of CD20 protein surface expression by internalization into the cytoplasm was also observed in some specific cases.16,42 Further molecular analysis of the down-regulation of CD20 protein after treatment with rituximab is needed.

Another interesting finding in our study is that all of the patients showed a CD20-negative phenotypic change were diagnosed as DLBCL. Two cases were diagnosed as FL at their first admission, but both were transformed into DLBCL when a CD20-negative change was observed. Furthermore, a CD20-negative change was confirmed in all 5 cases using tumor cells derived from the bone marrow and/or cerebral fluid. These findings may suggest that the clinical entity and progression pattern is partly related to CD20-negative phenotypic transformation. Further studies will be needed to confirm this idea.

Genetic mutations in the CD20 coding sequence were also observed in 2 cases, as shown in Table 2. These mutations led to amino acid alterations, including S97F and V247I, which are located at the second transmembrane domain and the C-terminal intracellular domain, respectively. A recent report suggested that neither site is recognized directly by rituximab.43 Although it is possible that these alterations led to a conformational change in the CD20 protein that interferes with rituximab binding, a more attractive explanation may be that the loss of expression is much more critical for resistance to rituximab than we originally suspected. Preliminary data using fluorescence-labeled rituximab indicate that rituximab fails to bind to RRBL1 cells (CD20-negative B cells) in vitro (data not shown), and that ADCC and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) activity in vitro are significantly lower than in CD20-positive B cells (CDC; data not shown). These data suggest that the loss of antibody binding due to the down-regulation of antigen expression is one critical mechanism underlying rituximab resistance. Further investigation will be needed to expand these observations.

Our observations also revealed a population of cells that are rituximab-resistant despite the presence of CD20 protein expression as observed by FCM, IHC, and immunoblotting (data not shown). In those patients, molecular mechanisms other than a loss of protein expression may have occurred, such as an amino acid alteration resulting from a genetic mutation of the MS4A1 gene, a posttranslational modification of the CD20 protein, abnormalities in the CD20 signal transduction pathway, antiapoptotic mechanisms of tumor cells, or aberrant metabolism of rituximab.9,44,45 The detailed mechanisms of these and other possibilities are still unclear.

Finally, in the specific cases reported herein, 5-Aza can stimulate CD20 mRNA and protein expression, resulting in the restoration of rituximab sensitivity in vitro. The DNA methyltransferase inhibitors 5-azacytidine and 5-Aza have been used in patients suffering from hematologic malignancies such as myelodysplastic syndrome.38,39,46 In the future, a combination of molecular targeting therapy using 5-Aza and rituximab may prove to be a unique strategy as a salvage therapy for CD20-negative transformed B-cell malignancies in certain patients. Further analysis of patients' primary cells and in vivo analysis using mouse xenograft lymphoma models are required.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tomoka Wakamatsu, Yukie Konishi, Mari Otsuka, Eriko Ushida, and Chieko Kataoka for valuable laboratory assistance. We also thank Yoko Kajiura, Yasuhiko Miyata, and Yuka Nomura for the FCM data analysis.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research (19-8) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, a Grant-in-Aid from the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (20591116) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Authorship

J.H. and A.T. designed experiments, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; T.S. and K.S. prepared clinical samples and performed research; M.I. and S.N. performed pathologic analyses; H.K. and T.K. analyzed data, designed experiments, and interpreted data; and T.N. supervised experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.K. is a consultant for a Kyowa Hakko Kogyo (Tokyo, Japan), and T.K. is funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan) and for Zenyaku Kogyo (Tokyo, Japan). The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Akihiro Tomita, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsurumai-cho 65, Showa-ku, Nagoya 466-8550, Japan; e-mail; atomita@med.nagoya-u.ac.jp.