Abstract

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) entry involves the interaction between the surface (SU) subunit of the Env proteins and cellular receptor(s). Previously, our laboratories demonstrated that heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) and neuropilin-1 (NRP-1), a receptor of VEGF165, are essential for HTLV-1 entry. Here we investigated whether, as when binding VEGF165, HSPGs and NRP-1 work in concert during HTLV-1 entry. VEGF165 binds to the b domain of NRP-1 through both HSPG-dependent and -independent interactions, the latter involving its exon 8. We show that VEGF165 is a selective competitor of HTLV-1 entry and that HTLV-1 mimics VEGF165 to recruit HSPGs and NRP-1: (1) the NRP-1 b domain is required for HTLV-1 binding; (2) SU binding to target cells is blocked by the HSPG-binding domain of VEGF165; (3) the formation of Env/NRP-1 complexes is enhanced by HSPGs; and (4) the HTLV SU contains a motif homologous to VEGF165 exon 8. This motif directly binds to NRP-1 and is essential for HTLV-1 binding to, internalization into, and infection of CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells. These findings demonstrate that HSPGs and NRP-1 function as HTLV-1 receptors in a cooperative manner and reveal an unexpected mimicry mechanism that may have major implications in vivo.

Introduction

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is a human retrovirus responsible for adult T-cell leukemia and inflammatory disorders.1 In vivo, HTLV-1 is primarily found in CD4+ T cells and can also infect CD8+ T cells, monocytes/macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs).2-4 In contrast to T cells, which are thought to be infected via cell-cell contact,5 DCs can be infected by cell-free HTLV-1 and efficiently transmit HTLV-1 to primary CD4+ T cells.6

The glucose transporter GLUT1 was the first molecule identified as a receptor for HTLV-1 and the related virus HTLV-2.7,8 Later studies showed that HTLV-1 could efficiently enter cells producing minimal levels of GLUT1 on the cell surface9 and that the amount of cell-surface GLUT1 did not correlate with levels of HTLV-1 binding,10 raising the hypothesis that other molecules can be used as receptors. Consistent with this, we reported that heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) and neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) are also critical for HTLV-1 entry.11-13

HSPGs are transmembrane proteins conjugated to negatively charged sulfated glycan chains. HSPGs have been shown to be essential for the HTLV-1 surface (SU) subunit binding to target cells11,14 as well as for HTLV-1 virus binding to and internalization into primary CD4+ T cells11,13 and DC-mediated infection of T cells.6 NRP-1 is a single-spanning domain membrane protein notably expressed by activated T cells12,15 and DCs.15,16 Previously, we demonstrated that NRP-1 binds to the HTLV-1 Env and regulates target cell infection by HTLV-1–pseudotyped particles. We also found that HTLV-1 Env can bridge NRP-1 and GLUT1, suggesting that these 2 molecules function together to promote HTLV-1 entry.12

NRP-1 is a coreceptor for certain isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), primarily VEGF165.17 VEGF165 triggers signal transduction through VEGF-receptor 2 (VEGF-R2); this signaling requires VEGF165 to be initially associated with NRP-1, a process mediated by both HSPG-dependent and HSPG-independent interactions.18-20 HSPGs bridge the heparin-binding domains of VEGF165 (exon 7 domain) and NRP-1 (b domain) and promote dimerization of the b domain of NRP-1.18,21,22 In addition, the exon 8–encoded domain of VEGF165 mediates binding to NRP-1 in the absence of heparin.18,23 Both exon 7 and exon 8 peptides interfere with the VEGF165/NRP-1 interaction.24-29 Moreover, in contrast to VEGF165, VEGF121 (which lacks exon 7) and VEGF165b (which lacks exon 8) bind poorly to NRP-1 and are not capable of bridging NRP-1 and VEGF-R2.23 This suggests that HSPG-mediated and direct interactions function cooperatively in forming an extended surface that allows stable binding of VEGF165 to NRP-1 (Figure 3A).18

In this study, we analyzed the respective roles of HSPGs and NRP-1 during HTLV-1 entry. We show that HTLV-1 mimics VEGF165 to recruit HSPGs and NRP-1 as primary entry receptors, making VEGF165 a potent natural inhibitor of HTLV-1 infection.

Methods

Cells and transfection

Adherent cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium and T cells in RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Blood from healthy donors was collected according to the National Institutes of Health–approved Institutional Review Board protocols, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-gradient centrifugation, and the lymphocytes and monocytes were separated by countercurrent elutriation as described.13 COS and 293T cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate precipitation method.

Amino acid sequence analyses

Sequences searches were performed using the UniProt Knowledgebase Release 12.6 as available at the Expasy server (http://www.expasy.org). Multiple sequence alignments were generated with the ClustalX program. The KPxR motif searches were initially performed using the ScanProsite interface of the Expasy server using specific taxonomy and sequence description filters.

Plasmids, recombinant proteins, and peptides

The pSG5M,30 CMV-Env-LTR,31 SU-rFc,32 PMT21-HA-NRP-1, and pMT21-sHA-NRP-1 plasmids12 have been previously described. To generate HA-NRP-1Δb, 2 AgeI cleavage sites were introduced in frame in the HA-NRP-1 plasmid at the junctions of the b domain. The plasmid was then digested by AgeI to release the b-domain fragment and religated. NRP-1-Fc, VEGFR2-Fc, and VEGF165 were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and Tuftsin (TKPR) from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). The VEGF165b control peptide (LTRKD), SU 90-94 (KKPNR), and Tuftsin analog (TU-A)(TKPPR) were from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium). The 15-mer SU peptides were described by Pique et al.33 The 24-mer exon 7 (CSCKNTDSRCKARQLENLERTCRC) and control 24-mer peptide were from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ). VEGF165 concentration was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D Systems).

BIAcore binding analysis

In vitro interactions were performed at 25°C with a BIAcore 2000 using HBS-EP buffer (10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 0.005% (vol/vol) surfactant P20). Recombinant proteins in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) were covalently coupled to a CM5 chip using an amine coupling kit. Regeneration of the sensor chip surface was achieved by running 5 μL HCl, 100 mM, and 5 μL NaOH, 100 mM through the flow cell at 30 μL/min. Injected molecules were perfused at a flow rate of 20 μL/min, and the resonance changes were recorded. The sensorgram of the immobilized surface was subtracted from that of the control surface, and the data were analyzed with BIAevaluation software (GE Healthcare, Orsay, France).

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblot, and pull-down

Transfected cells were lysed in lysis buffer12 containing mixed protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). Cell lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with sera from HTLV-1–infected persons before the addition of Protein-G Sepharose beads for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed 5 times in lysis buffer, and proteins were eluted by boiling for 5 minutes in Laemmli buffer. Immunoblot analysis were performed using either the anti-SU 4D4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) provided by Claude Desgranges (Institut Cochin, Paris, France)34 or the anti-HA antibody (Roche Diagnostics). For quantification, briefly exposed films were scanned with an AGFA scanner, and signal densities of Env or HA-sNRP-1 bands were measured with ImageJ software using the same area. Signal density in the empty lane was also measured and subtracted from the signal of each band. The percentage of coprecipitated HA-sNRP-1 (amount of HA-sNRP-1 in the IP/amount of HA-sNRP-1 in the cell lysate) was calculated for each condition and was normalized to the level of Env quantified in cell lysates. The percentage of precipitation found for wt HA-sNRP-1 was set as 100% for comparison.

For heparin pull-down, cell lysates were incubated with 50 μL of a 20% suspension of Sepharose-heparin beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed 5 times in lysis buffer and proteins eluted by boiling for 5 minutes in Laemmli.

Cell-surface expression of HSPGs and NRP-1

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with either the anti-HSPG F58-10E4 (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan) or the anti–NRP-1 BDCA4 (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) mAb.11,12 For removal of HSPGs, cells (106) were resuspended in 200 μL heparan sulfate (HS) lyase buffer and then incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with 10 mU HS lyase (Seikagaku).13

HTLV-1 SU and virion binding assay

The soluble SU protein from HTLV-1 (SU-rFc) or avian retrovirus (SU-ASLV-rFc) was obtained as described.13 The amount of SU protein was determined using a rabbit IgG ELISA (ZeptoMetrix, Buffalo, NY), and 200 ng of each SU protein was used. Specific binding of SU-rFc proteins were performed as previously described.13

HTLV-1 viral stocks were prepared from HTLV-1–producing cells (MT-2) and the concentration determined by ELISA (ZeptoMetrix) as previously described.13 Target cells (106) were then incubated at 22°C with either the concentrated HTLV-1 stock (5 μg unless otherwise noted) or 10 μL RPMI (negative control) and the amount of virus binding determined by flow cytometry as previously described.13

HTLV-1 internalization assay

Studies to examine the internalization of HTLV virions were performed as described.13 For monocyte-derived DCs (MDDCs), cells were incubated with 25 μL of either culture medium (or for Figure 6B, with supernatants from uninfected T cells) as negative control and with either a 1/1000 dilution of concentrated virus stocks or fresh virus-containing supernatants from HTLV-1–producing cells (MT-2) at 37°C for 2 hours. For HIV-1 internalization, HIV-1 virions (100 ng/mL) were added on MOLT4 or MDDC cultures for 2 hours at 37°C and internalization of HIV-1 cores detected with an anti-HIV core antibody (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Infection assays

HTLV-1 or HIV-1 virions were obtained from supernatants of concentrated MT-2 cells or from supernatants or HIV-1–transfected 293T cells, respectively. HTLV-1 or HIV-1 virus concentration was determined by ELISA. Cells were incubated with virus for 3 hours, washed, and replated in 6-well plates at 5 × 105/well. For experiments in which HTLV-1 infection was determined by Tax staining, cells were harvested 48 hours after infection and the amount of intracellular Tax determined by flow cytometry. For experiments in which infection was determined from Gag levels, the cells were washed and refed at days 2, 4, and 6, and the culture supernatants were harvested on day 7 (for DC) or washed at day 2 and collected on day 3 (for T cells) and the virus concentrations determined by p19 (for HTLV-1) or p24 (for HIV-1).

Results

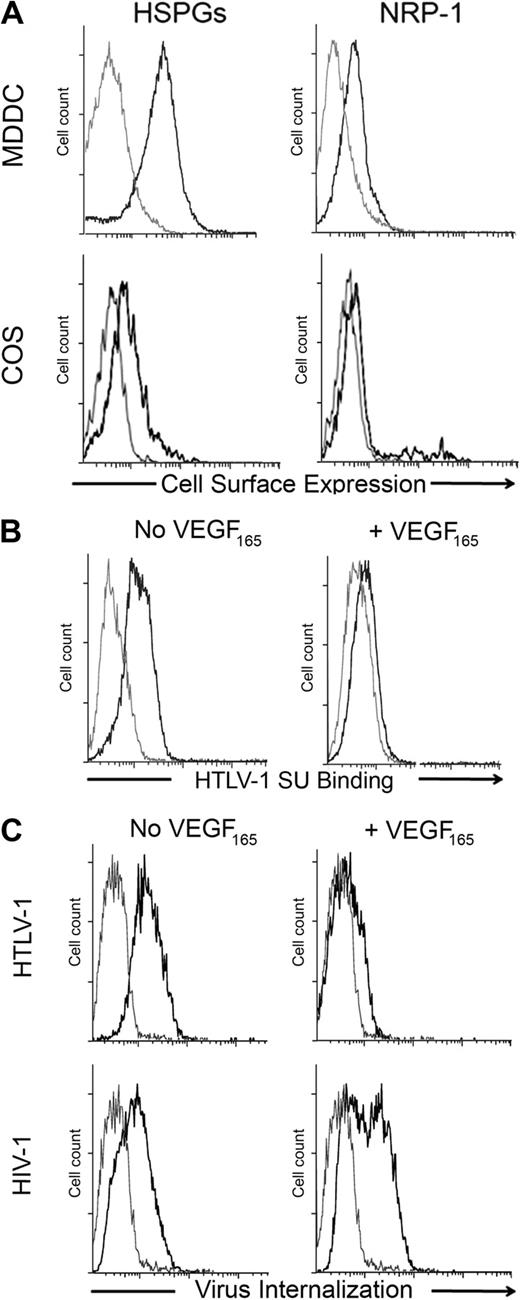

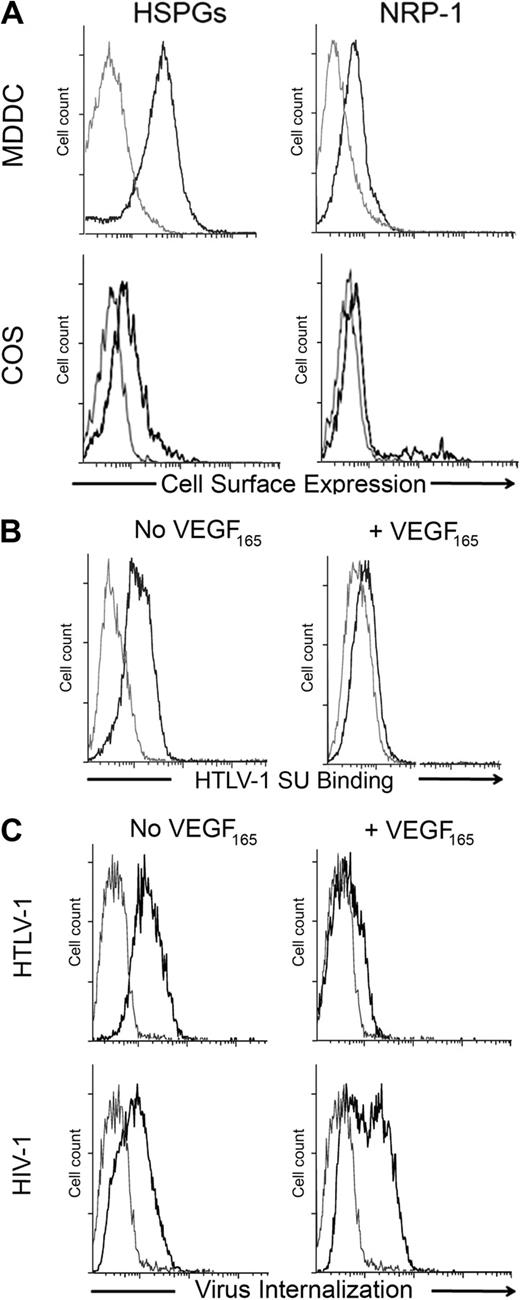

VEGF165 blocks HTLV-1 entry into primary DCs

Previously, we reported that the natural NRP-1 ligand VEGF165 blocks binding of the HTLV-1 Env SU to adherent cells.12 Jones et al recently demonstrated that DCs, including MDDCs, can be infected with cell-free HTLV-1 virions.6 We took advantage of this new model to examine whether VEGF165 can block HTLV-1 entry and infection to physiologically relevant target cells. We verified that MDDC expressed a high level of cell-surface HSPGs and NRP-1, compared with COS cells (used in Figure 3B for NRP-1 overexpression; Figure 1A). We found that VEGF165 dramatically reduced the binding of SU to MDDCs (Figure 1B) as well as HTLV-1 virus internalization into MDDCs (Figure 1C top panel). In contrast, VEGF165 did not reduce internalization of HIV-1, which infects MDDCs using different receptors (Figure 1C bottom panels). These data demonstrate that VEGF165 is a selective and potent competitor of HTLV-1 entry into primary DCs.

Exogenous VEGF165 inhibits HTLV-1 entry into primary DCs. (A) Cell- surface levels of HSPGs or NRP-1 on primary MDDCs and COS cells. The gray lines represent the isotype control; black lines, staining with the anti-HSPG (10E4) or anti-NRP-1 (BDCA4) mAb, as indicated. (B) Effect of exogenous VEGF165 on the binding of the HTLV-1 SU to MDDCs. MDDCs were incubated in the presence or absence of VEGF165 (50 ng/mL) for 30 minutes and then exposed to the HTLV-1 SU-rFc (black lines) or the control SU-ASLV-rFc (gray lines) and the level of binding determined. (C) Effect of exogenous VEGF165 on the internalization of HTLV-1 or HIV-1 into MDDCs. MDDCs were incubated in the presence or absence of VEGF165 (50 ng/mL) for 30 minutes and then with culture medium (gray lines) or 100 ng/mL of either HTLV-1 (top panels) or HIV-1 (bottom panels) virions (black lines). After 2 hours at 37°C, MDDCs were permeabilized, stained with an antibody directed against the viral core proteins (HTLV-1 MAp19 or HIV-1 CAp24), and virus internalization determined.

Exogenous VEGF165 inhibits HTLV-1 entry into primary DCs. (A) Cell- surface levels of HSPGs or NRP-1 on primary MDDCs and COS cells. The gray lines represent the isotype control; black lines, staining with the anti-HSPG (10E4) or anti-NRP-1 (BDCA4) mAb, as indicated. (B) Effect of exogenous VEGF165 on the binding of the HTLV-1 SU to MDDCs. MDDCs were incubated in the presence or absence of VEGF165 (50 ng/mL) for 30 minutes and then exposed to the HTLV-1 SU-rFc (black lines) or the control SU-ASLV-rFc (gray lines) and the level of binding determined. (C) Effect of exogenous VEGF165 on the internalization of HTLV-1 or HIV-1 into MDDCs. MDDCs were incubated in the presence or absence of VEGF165 (50 ng/mL) for 30 minutes and then with culture medium (gray lines) or 100 ng/mL of either HTLV-1 (top panels) or HIV-1 (bottom panels) virions (black lines). After 2 hours at 37°C, MDDCs were permeabilized, stained with an antibody directed against the viral core proteins (HTLV-1 MAp19 or HIV-1 CAp24), and virus internalization determined.

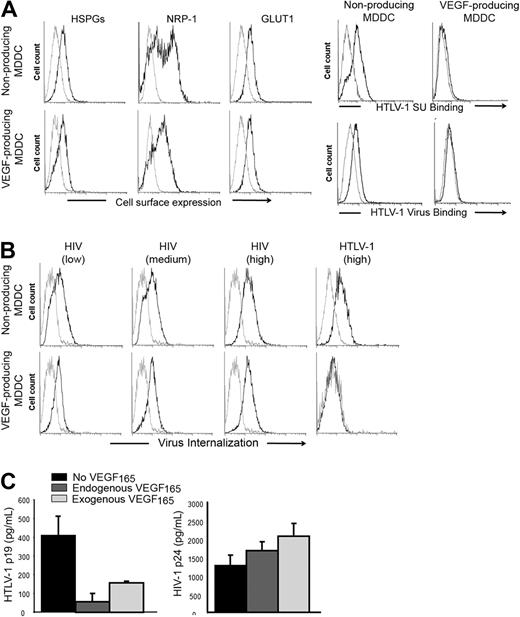

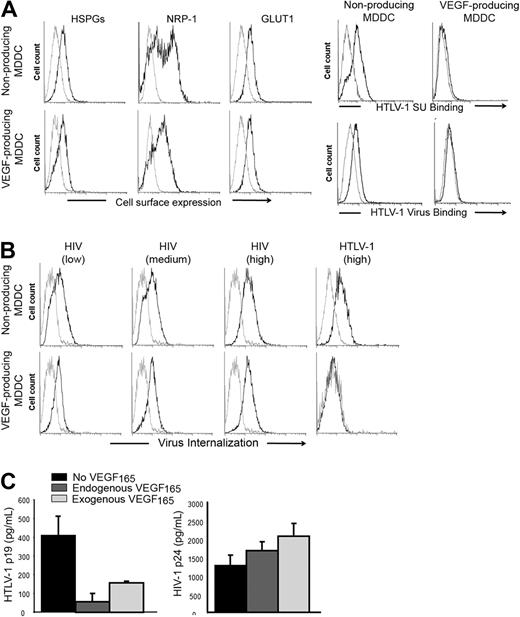

Endogenous production of VEGF165 correlates with reduced HTLV-1 interaction with MDDC

Although MDDC generated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of monocytes do not produce VEGF165, stimulation with both LPS and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) leads to VEGF165 secretion.35 We took advantage of these alternative culture conditions to evaluate whether endogenous production of VEGF165 would also modulate HTLV-1 entry. We confirmed that LPS/PGE2-treated MDDCs produced VEGF165 (1700-2200 pg/mL), whereas the VEGF165 production by LPS-stimulated MDDCs was barely detectable (< 30 pg/mL). The levels of cell-surface HSPGs and GLUT1 were comparable between VEGF165-producing and nonproducing MDDCs (Figure 2A left panels). The level of NRP-1 was slightly reduced in VEGF165-producing relative to nonproducing MDDCs, which was unexpected because VEGF165 has been shown to up-regulate NRP-1.36 We assumed, therefore, that the lower NRP-1 signal observed in VEGF165-producing MDDCs reflected competition between the anti–NRP-1 antibody and VEGF165 for NRP-1 binding, rather than reduced production of NRP-1. Culturing MDDCs in conditions where they produce VEGF165 almost completely abolished their ability to bind to either the HTLV-1 SU or virions (Figure 2A right panels) or to internalize HTLV-1 virions (Figure 2B HTLV panels). Comparable levels of HIV-1 internalization were detected in the 2 MDDC populations, even when a low dose of HIV-1 was used (Figure 2B HIV panels). The level of cell-free HTLV-1 infection in MDDC-producing VEGF165 was also significantly lower relative to the level in the nonproducing MDDCs (Figure 2C left panel). When the MDDCs were infected in the presence of exogenous VEGF165, the level of infection was also reduced, although the effect was less dramatic; this may reflect lability of added VEGF165 and/or cell-cell spread after the initial infection. As expected, HIV infection of MDDCs was not inhibited by either endogenous or exogenous VEGF165 (Figure 2C right panel). These differences in HTLV-1 binding, internalization, and infection are probably the result of continuous VEGF165 production by MDDCs, although the contribution of other secreted molecules could not be excluded. Along with the findings showing the inhibitory effect of exogenous VEGF165, these results provide strong evidence that VEGF165 is a natural regulator of HTLV-1 infection in vivo.

Endogenous production of VEGF165 by MDDCs correlates with reduced HTLV-1 entry. (A) Effect of endogenous VEGF165 production by MDDCs on receptor expression or HTLV-1 binding. (Left panels) Cell-surface expression of HSPGs, NRP-1, and GLUT-1 on nonproducing (LPS stimulation) and VEGF165-producing (LPS + PGE2 stimulation) MDDCs, determined by flow cytometry. (Right panels) Nonproducing and VEGF165-producing MDDCs were incubated with either HTLV-1 SU or HTLV-1 virions (black lines) or control SU-ASLV-rFc or medium (gray lines) and the amount of binding determined. (B) Effect of endogenous VEGF165 production by MDDCs on the internalization of HTLV-1 or HIV-1 virus. Nonproducing (top panels) and VEGF165-producing (bottom panels) MDDCs were incubated with culture medium (gray lines), and 25 ng/mL (low), 50 ng/mL (medium), or 100 ng/mL (high) HIV-1 (black lines) or with culture medium (gray line) or 100 ng/mL HTLV-1 (black line) and the amount of internalization was determined. (C) Effect of endogenous VEGF165 production by MDDCs on HTLV-1 or HIV-1 infection. MDDCs were infected with 100 ng of either HTLV-1 or HIV-1 virions. Seven days later, supernatants from individual wells were collected (8 wells/condition), and MDDC infection was measured by quantifying the concentration in supernatants of the viral core protein, MAp19 for HTLV-1 (left histogram) or CAp24 for HIV-1 (right histogram). The data are the mean ± SD of 1 representative experiment of 3 performed in octuplicate.

Endogenous production of VEGF165 by MDDCs correlates with reduced HTLV-1 entry. (A) Effect of endogenous VEGF165 production by MDDCs on receptor expression or HTLV-1 binding. (Left panels) Cell-surface expression of HSPGs, NRP-1, and GLUT-1 on nonproducing (LPS stimulation) and VEGF165-producing (LPS + PGE2 stimulation) MDDCs, determined by flow cytometry. (Right panels) Nonproducing and VEGF165-producing MDDCs were incubated with either HTLV-1 SU or HTLV-1 virions (black lines) or control SU-ASLV-rFc or medium (gray lines) and the amount of binding determined. (B) Effect of endogenous VEGF165 production by MDDCs on the internalization of HTLV-1 or HIV-1 virus. Nonproducing (top panels) and VEGF165-producing (bottom panels) MDDCs were incubated with culture medium (gray lines), and 25 ng/mL (low), 50 ng/mL (medium), or 100 ng/mL (high) HIV-1 (black lines) or with culture medium (gray line) or 100 ng/mL HTLV-1 (black line) and the amount of internalization was determined. (C) Effect of endogenous VEGF165 production by MDDCs on HTLV-1 or HIV-1 infection. MDDCs were infected with 100 ng of either HTLV-1 or HIV-1 virions. Seven days later, supernatants from individual wells were collected (8 wells/condition), and MDDC infection was measured by quantifying the concentration in supernatants of the viral core protein, MAp19 for HTLV-1 (left histogram) or CAp24 for HIV-1 (right histogram). The data are the mean ± SD of 1 representative experiment of 3 performed in octuplicate.

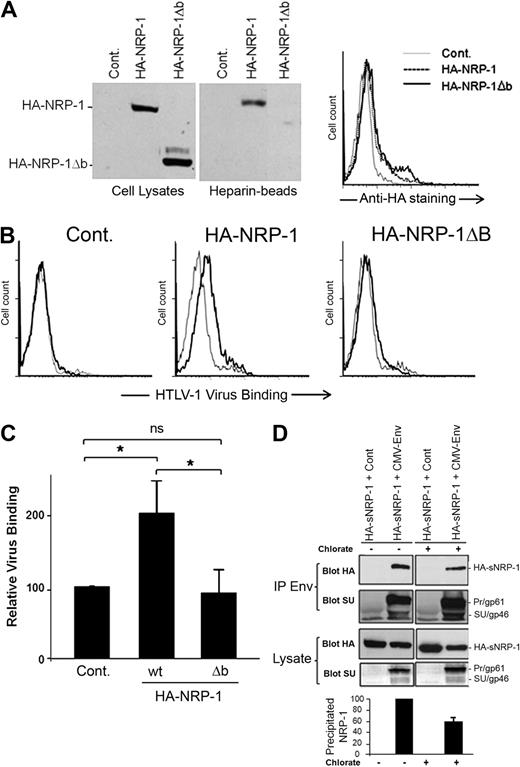

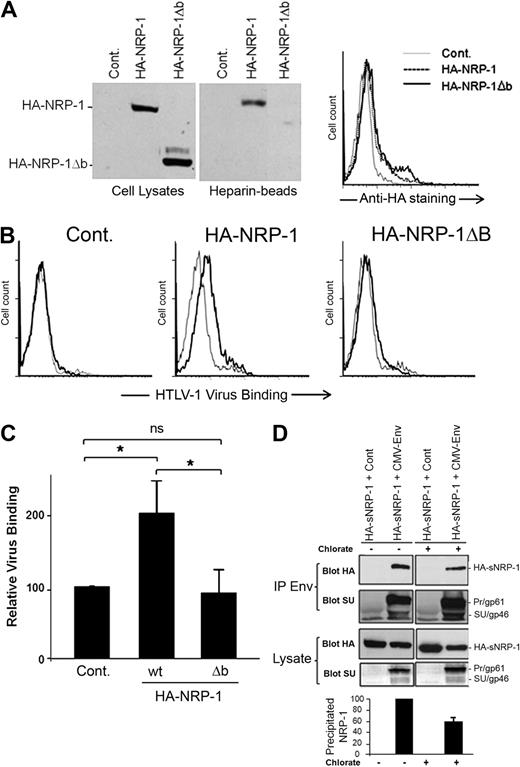

The b domain of NRP-1 is essential for HTLV-1 binding to target cells

Because the HSPGs and VEGF165 binding sites have been mapped to the b domain of NRP-1,18,22 we investigated the impact of b-domain deletion on the binding of HTLV-1 to the cell surface. To facilitate the study of the effect of exogenously expressed NRP-1, these experiments were performed in cells that produced low level of endogenous NRP-1 (COS; Figure 1A). The level of cell-surface expression similar to that of wild-type NRP-1 was previously considered as one of the criteria of proper folding for neuropilin mutants.37,38 We found that an NRP-1 mutant lacking the b domain (HA-NRP-1Δb) was synthesized and expressed at the cell surface at comparable level than WT HA-NRP-1 in COS cells (Figure 3A), indicating that deletion of the b domain did not induce misfolding of the mutant. As expected, we also observed that wt HA-NRP-1, but not HA-NRP-1Δb, was capable of binding heparin (Figure 3A). Consistent with their low expression of endogenous NRP-1, a very low level of virus binding was observed on COS cells transfected with the control plasmid. Virus binding was increased on cells overexpressing wt HA-NRP-1, whereas binding was reduced to almost control level in cells overexpressing HA-NRP-1Δb (Figure 3B). Statistical analysis indicated a significant difference in binding between COS cells overexpressing HA-NRP-1 (200% ± 49%) and either control cells (normalized to 100%) or cells overexpressing HA-NRP-1Δb (94% ± 32%; Figure 3C). Hence, the b domain of NRP-1 is essential for binding of HTLV-1 to target cells, accounting for the competitive effect of VEGF165 on HTLV-1 entry.

The HTLV-1 SU/NRP-1 interaction depends on the b domain of NRP-1 and on HSPGs. (A) Effect of the deletion of the b domain of NRP-1 on NRP-1 synthesis, binding to heparin, and cell-surface expression. COS cells were transfected with a control plasmid (Cont.) or a plasmid encoding either wild-type (wt) HA-NRP-1 or HA-NRP-1Δb. (Left panels) Total cell proteins and proteins pulled-down on heparin-coated Sepharose beads were analyzed by immunoblot using an anti-HA mAb. (Right panel) Transfected COS cells were stained with the anti-HA mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Effect of deletion of the b domain of NRP-1 on HTLV-1 virus binding. COS cells transfected as in panel A were incubated with culture medium (gray lines) or concentrated supernatant from HTLV-1–infected T cells (black lines), and the level of binding of HTLV-1 virions was determined. (C) Quantification of the level of HTLV-1 virus binding to COS cells overexpressing wt HA-NRP-1 or HA-NRP-1Δb. Results correspond to the ratio between the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cells overexpressing either WT HA-NRP-1 or HA-NRP-1Δb and the MFI of control cells (×100) and are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *Statistically significant (unpaired t test analysis, 2-tailed P < .05). ns indicates not significant. (D) Effect of reducing HSPG synthesis on the formation of complexes between the HTLV-1 Env proteins and the ectodomain of NRP-1. COS cells were cotransfected with either the CMV-Env-LTR construct or a control plasmid and a plasmid encoding the soluble version of HA-NRP-1 (HA-sNRP-1). After 4 hours, cells were either left untreated (−) or treated with 30 mM sodium chlorate for 24 hours (+). Total proteins precipitated with an anti–HTLV-1 serum (IP Env) were examined by immunoblot using the anti-HA or the anti-SU mAb, as indicated. The levels of HA-NRP-1 and Env in cell lysates are also shown. The positions of HA-sNRP-1 and of the HTLV-1 Env precursor (gp61) and SU (gp46) are indicated. (Bottom panel) Quantification of the effect of sodium chlorate on the Env/HA-sNRP-1 coprecipitation. Results represent the normalized amount of HA-sNRP-1 coprecipitated with Env and are the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments.

The HTLV-1 SU/NRP-1 interaction depends on the b domain of NRP-1 and on HSPGs. (A) Effect of the deletion of the b domain of NRP-1 on NRP-1 synthesis, binding to heparin, and cell-surface expression. COS cells were transfected with a control plasmid (Cont.) or a plasmid encoding either wild-type (wt) HA-NRP-1 or HA-NRP-1Δb. (Left panels) Total cell proteins and proteins pulled-down on heparin-coated Sepharose beads were analyzed by immunoblot using an anti-HA mAb. (Right panel) Transfected COS cells were stained with the anti-HA mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Effect of deletion of the b domain of NRP-1 on HTLV-1 virus binding. COS cells transfected as in panel A were incubated with culture medium (gray lines) or concentrated supernatant from HTLV-1–infected T cells (black lines), and the level of binding of HTLV-1 virions was determined. (C) Quantification of the level of HTLV-1 virus binding to COS cells overexpressing wt HA-NRP-1 or HA-NRP-1Δb. Results correspond to the ratio between the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cells overexpressing either WT HA-NRP-1 or HA-NRP-1Δb and the MFI of control cells (×100) and are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *Statistically significant (unpaired t test analysis, 2-tailed P < .05). ns indicates not significant. (D) Effect of reducing HSPG synthesis on the formation of complexes between the HTLV-1 Env proteins and the ectodomain of NRP-1. COS cells were cotransfected with either the CMV-Env-LTR construct or a control plasmid and a plasmid encoding the soluble version of HA-NRP-1 (HA-sNRP-1). After 4 hours, cells were either left untreated (−) or treated with 30 mM sodium chlorate for 24 hours (+). Total proteins precipitated with an anti–HTLV-1 serum (IP Env) were examined by immunoblot using the anti-HA or the anti-SU mAb, as indicated. The levels of HA-NRP-1 and Env in cell lysates are also shown. The positions of HA-sNRP-1 and of the HTLV-1 Env precursor (gp61) and SU (gp46) are indicated. (Bottom panel) Quantification of the effect of sodium chlorate on the Env/HA-sNRP-1 coprecipitation. Results represent the normalized amount of HA-sNRP-1 coprecipitated with Env and are the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments.

HSPGs enhance the formation of Env/NRP-1 complexes

We next studied whether HSPGs could enhance the binding of the HTLV-1 SU to NRP-1. Such studies require the quantification of Env/NRP-1 complexes and could therefore not be performed by flow cytometry, which could not distinguish between SU binding on HSPG/NRP-1 complexes and SU binding directly to HSPGs or other molecules. Therefore, the effect of HSPG was examined using the immunoprecipitation approach we previously used to demonstrate the interaction of NRP-1 and Env.12 The HTLV-1 Env proteins are synthesized as a precursor (Pr; gp61) subsequently cleaved into SU (gp46) and TM (gp21) in the Golgi apparatus.39 We reasoned that, because heparan chain synthesis also occurs in the Golgi,40 immunoprecipitation of intracellular proteins could be used to study the HSPG/SU interaction. Cells were cotransfected with a plasmid allowing the production of the precursor as well the cleaved forms of Env and a plasmid encoding the ectodomain of NRP-1 (HA-sNRP-1) to study the formation of complexes with Env and the extracellular part of NRP-1. Transfected COS cells were cultured for 24 hours with or without sodium chlorate (NaClO3), an inhibitor of heparan chain sulfation.13 NaClO3 treatment reduced the amount of cell-surface HSPGs by approximately 70% (data not shown) but had little effect on Env or HA-sNRP-1 synthesis in COS cells (Figure 3D). In contrast, lower HSPG synthesis was associated with a 40% reduction in the amount of HA-sNRP-1 coprecipitated with Env, relative to untreated cells (Figure 3D). Hence, the formation of intracellular complexes between the HTLV-1 Env proteins and the ectodomain of NRP-1 partially depends on HSPGs.

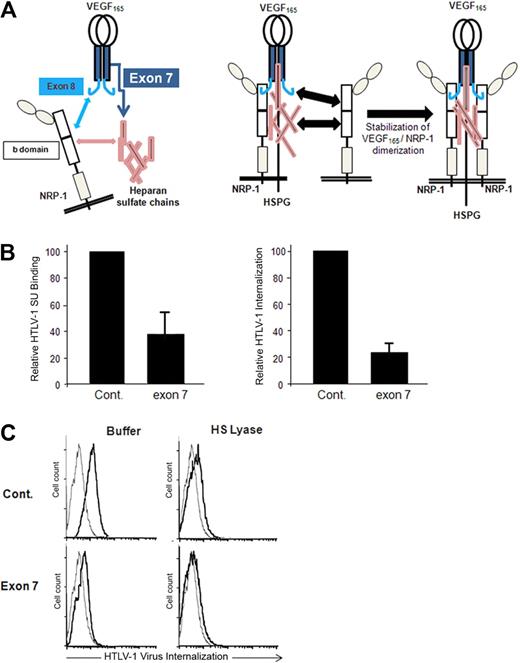

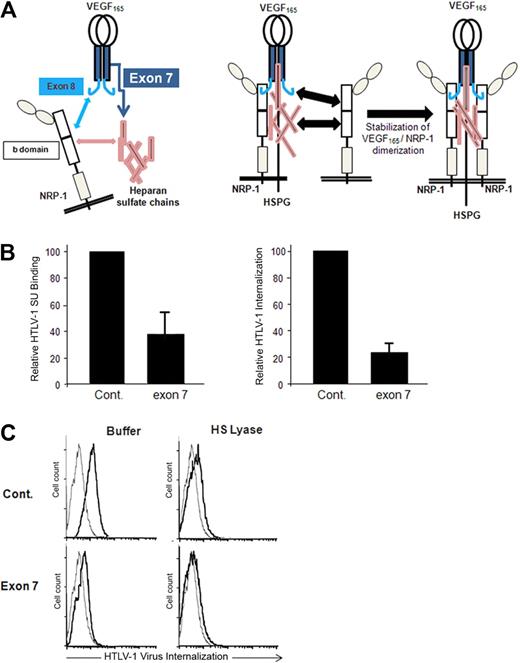

A VEGF165 exon 7 peptide blocks HTLV-1 entry

A peptide corresponding to the exon 7–encoded domain of VEGF165, which mediates the HSPG-dependent binding to NRP-1 (Figure 4A), was shown to block the VEGF165/NRP-1 interaction.25,29 Using primary CD4+ T cells, we found that the exon 7 peptide strongly reduced HTLV-1 SU binding as well as HTLV-1 internalization, compared with binding and internalization in the presence of the control peptide (Figure 4B). The exon 7 peptide, but not the control peptide, also inhibited HTLV-1 internalization into DCs, and this effect was similar to that observed when cell-surface HSPGs were enzymatically removed by HS lyase (Figure 4C). Combination of HS lyase and exon 7 further reduced HTLV-1 internalization into DCs. This additive effect could be the consequence of concomitant reduction in HTLV-1 attachment on free HSPGs (because of the action of HS lyase) and in HTLV binding on HSPG/NRP-1 complexes (because of addition of the exon 7 peptide). These findings indicate that native HTLV-1 Env binding to NRP1 involves the same structure recognized by the VEGF165 exon 7 domain, that is, the interface formed between heparan sulfate chains and the b domain of NRP-1.

HTLV-1 interactions with primary CD4+ T cells and MDDCs are blocked by the HSPG-binding domain of VEGF165. (A) Schematic representation of the interactions between VEGF165, heparan sulfate chains, and NRP-1. (Left panel) The interactions between VEGF165 exon 7 and heparan sulfate chains (dark blue arrow), between VEGF165 exon 8 and the b domain of NRP-1 (light blue arrow), and between the b domain of NRP-1 and heparan sulfate chains (pink arrow). (Right diagram) The impact of these interactions on the formation of HSPG/NRP-1/VEGF165 complexes and on NRP-1 dimerization. The subsequent recruitment of VEGF-R2 by VEGF165 bound to HSPG/NRP-1 complexes is not depicted. (B) Effect of the VEGF165 exon 7 peptide on HTLV-1entry into CD4+ T cells. Primary activated CD4+ T cells were incubated for 30 minutes with either a peptide homologous to a portion of VEGF165 exon 7 or a control peptide of the same length and the levels of HTLV-1 SU binding (left histogram) or HTLV-1 virus internalization (right histogram) determined. The data are normalized to the control peptide (100%) and are the mean ± SD of 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. (C) Effects of HS lyase and exon 7 peptide on HTLV-1 entry into DCs. DCs were resuspended in HS lyase buffer and incubated in the presence or absence of HS lyase. The cells were then washed, incubated for 30 minutes with either the control peptide or VEGF165 exon 7 peptide, and incubated with either culture medium (gray lines) or HTLV-1 virions (black lines), and the extent of HTLV-1 virus internalization was determined.

HTLV-1 interactions with primary CD4+ T cells and MDDCs are blocked by the HSPG-binding domain of VEGF165. (A) Schematic representation of the interactions between VEGF165, heparan sulfate chains, and NRP-1. (Left panel) The interactions between VEGF165 exon 7 and heparan sulfate chains (dark blue arrow), between VEGF165 exon 8 and the b domain of NRP-1 (light blue arrow), and between the b domain of NRP-1 and heparan sulfate chains (pink arrow). (Right diagram) The impact of these interactions on the formation of HSPG/NRP-1/VEGF165 complexes and on NRP-1 dimerization. The subsequent recruitment of VEGF-R2 by VEGF165 bound to HSPG/NRP-1 complexes is not depicted. (B) Effect of the VEGF165 exon 7 peptide on HTLV-1entry into CD4+ T cells. Primary activated CD4+ T cells were incubated for 30 minutes with either a peptide homologous to a portion of VEGF165 exon 7 or a control peptide of the same length and the levels of HTLV-1 SU binding (left histogram) or HTLV-1 virus internalization (right histogram) determined. The data are normalized to the control peptide (100%) and are the mean ± SD of 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. (C) Effects of HS lyase and exon 7 peptide on HTLV-1 entry into DCs. DCs were resuspended in HS lyase buffer and incubated in the presence or absence of HS lyase. The cells were then washed, incubated for 30 minutes with either the control peptide or VEGF165 exon 7 peptide, and incubated with either culture medium (gray lines) or HTLV-1 virions (black lines), and the extent of HTLV-1 virus internalization was determined.

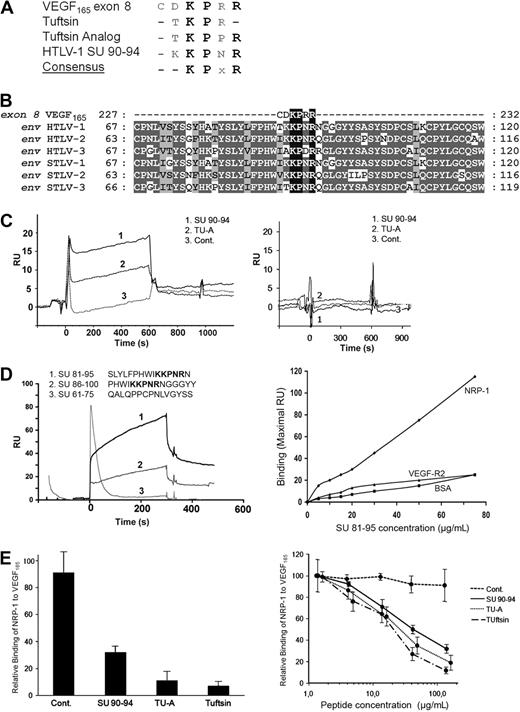

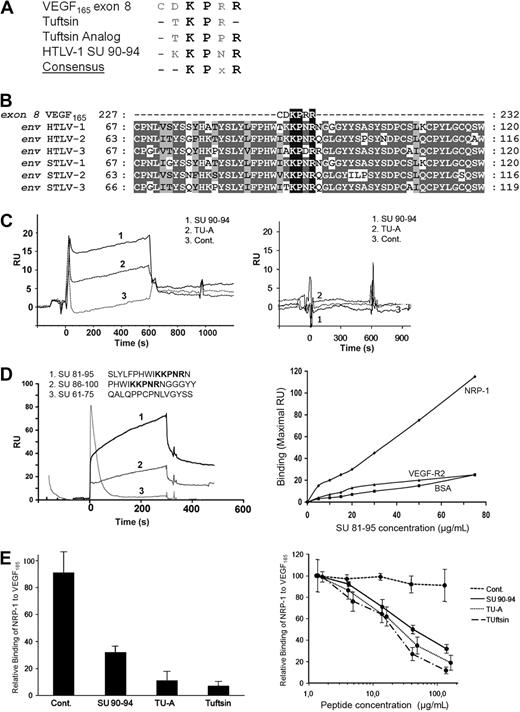

The HTLV SUs contain a conserved VEGF165 exon 8–like motif

VEGF165 also contains an HSPG-independent NRP-1 binding site, which corresponds to the exon 8–encoded domain23,26 (Figure 4A). Examination of the primary sequence of the HTLV-1 Env revealed strong homology between the SU 90-94 region (KKPNR) and the VEGF165 exon 8 domain (CDKPRR). Exon 8–related peptides, which also bind to NRP-1,28 Tuftsin (TKPR), and Tuftsin analog (TKPPR), are also highly homologous to the HTLV-1 SU 90-94 region. Strikingly, the KPxR consensus motif that can be deduced from these 4 sequences contains the 3 residues of VEGF165 previously shown to be critical for direct interaction with NRP-124,26 (Figure 5A).

The HTLV-1 SU contains a KPxR motif homologous to the VEGF165 exon 8 domain. (A) Sequence alignment between the VEGF165 exon 8 domain, the exon 8–like peptides Tuftsin and Tuftsin analog, and the aa 90-94 region of the HTLV-1 SU. The conserved consensus KPxR motif deduced from the alignment is also shown. (B) Local sequence alignment of VEGF165 exon 8 sequence with the region of the HTLV/STLV SUs encompassing the KPxR motif. Sequence positions corresponding to conserved and chemically homologous residues between viral sequences are highlighted in dark and light gray, respectively, and the KPxR motif is highlighted in black. The UniProt sequences used for the alignment are, respectively, VEGFA_HUMAN, ENV_HTL1A, ENV_HTLV2, ENV_HTL3P, O41897_9STL1, O09243_9DELA, and Q6XQ01_9DELA. The numbering refers to the complete unprocessed sequences. (C) In vitro binding of exon 8–like peptides to NRP-1 in the BIAcore system. The SU 90-94 peptide, Tuftsin analog (TU-A), or the control peptide (Cont.) was injected (15 μM each) on either recombinant NRP-1 (left panel) or recombinant VEGF-R2 (right panel) previously immobilized on the sensor chip. The sensorgram displays the kinetics of peptide binding after injection (time 0) and is 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. RU indicates resonance unit. (D) In vitro binding of longer SU peptides to NRP-1 in the BIAcore system. Fifteen-mer SU peptides either containing or lacking the KPxR motif (shown in bold) were injected (10 μM each) on recombinant NRP-1 immobilized on the sensor chip. (Left panel) The kinetics of peptide binding to NRP-1 after injection (time 0), which is 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. (Right panel) The binding of the SU 81-95 peptide on NRP-1, corresponding to the maximal RU value of the binding curve, and the absence of binding on BSA or VEGF-R2. (E) The SU 90-94 and exon 8–like peptides compete with VEGF165 for NRP-1 binding. (Left panel) Recombinant NRP-1 was injected on immobilized VEGF165 in the presence of buffer or of the SU 90-94, Tuftsin, Tuftsin analog (TU-A), or control peptide (100 μM each). The maximal RU value of each curve was used to quantify NRP-1 binding to VEGF165, and binding was normalized to condition without peptide (100%). Data are the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments. (Right panel) Dose-dependent inhibition of the NRP-1/VEGF165 interaction by the SU 90-94 and exon 8–like peptides.

The HTLV-1 SU contains a KPxR motif homologous to the VEGF165 exon 8 domain. (A) Sequence alignment between the VEGF165 exon 8 domain, the exon 8–like peptides Tuftsin and Tuftsin analog, and the aa 90-94 region of the HTLV-1 SU. The conserved consensus KPxR motif deduced from the alignment is also shown. (B) Local sequence alignment of VEGF165 exon 8 sequence with the region of the HTLV/STLV SUs encompassing the KPxR motif. Sequence positions corresponding to conserved and chemically homologous residues between viral sequences are highlighted in dark and light gray, respectively, and the KPxR motif is highlighted in black. The UniProt sequences used for the alignment are, respectively, VEGFA_HUMAN, ENV_HTL1A, ENV_HTLV2, ENV_HTL3P, O41897_9STL1, O09243_9DELA, and Q6XQ01_9DELA. The numbering refers to the complete unprocessed sequences. (C) In vitro binding of exon 8–like peptides to NRP-1 in the BIAcore system. The SU 90-94 peptide, Tuftsin analog (TU-A), or the control peptide (Cont.) was injected (15 μM each) on either recombinant NRP-1 (left panel) or recombinant VEGF-R2 (right panel) previously immobilized on the sensor chip. The sensorgram displays the kinetics of peptide binding after injection (time 0) and is 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. RU indicates resonance unit. (D) In vitro binding of longer SU peptides to NRP-1 in the BIAcore system. Fifteen-mer SU peptides either containing or lacking the KPxR motif (shown in bold) were injected (10 μM each) on recombinant NRP-1 immobilized on the sensor chip. (Left panel) The kinetics of peptide binding to NRP-1 after injection (time 0), which is 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. (Right panel) The binding of the SU 81-95 peptide on NRP-1, corresponding to the maximal RU value of the binding curve, and the absence of binding on BSA or VEGF-R2. (E) The SU 90-94 and exon 8–like peptides compete with VEGF165 for NRP-1 binding. (Left panel) Recombinant NRP-1 was injected on immobilized VEGF165 in the presence of buffer or of the SU 90-94, Tuftsin, Tuftsin analog (TU-A), or control peptide (100 μM each). The maximal RU value of each curve was used to quantify NRP-1 binding to VEGF165, and binding was normalized to condition without peptide (100%). Data are the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments. (Right panel) Dose-dependent inhibition of the NRP-1/VEGF165 interaction by the SU 90-94 and exon 8–like peptides.

The HTLVs, along with their simian counterparts (STLVs), belong to the primate T-cell lymphotropic virus (PTLV) group of δ retroviruses. Sequence analyses revealed that the KPxR motif was conserved in the SU proteins of HTLV-2, HTLV-3, and related STLVs (Figure 5B). Moreover, the KPxR sequence was present as a single copy and at an identical position in the SU of virtually all the PTLV sequences available in data banks (Table 1). Interestingly, the motif was not found in the SU sequences of bovine leukemia virus, another δ retrovirus that uses a different cell receptor than HTLV-1.41 The KPxR motif was found in less than 14% of SU sequences from lentiviruses and, among them, in only 0.5% of HIV-1 sequences, consistent with our previous observations that the HIV-1 Env does not bind to NRP-1.12 Finally, the KPxR motif was found in less than 6% of the Env proteins from γ or α retroviruses. The motif was found in the single available sequence from equine foamy virus, but in that case was located in the extracellular part of the TM, which is not involved in receptor recognition. This comparison clearly shows that the presence of a conserved KPxR motif in the SU is a specific feature of the HTLV/STLV family.

The SU 90-94 region is a direct binding site to NRP-1

Given the homology between the SU 90-94 and exon 8 sequences, we examined using the BIAcore system whether a SU 90-94 peptide also directly binds to NRP-1, as previously demonstrated for VEGF165 exon 8 and Tuftsin.18,23 Recombinant NRP-1 or, as a control, VEGF-R2, was immobilized on the sensor chip and the peptides were injected (Figure 5C). Because the amplitude of the signal obtained in the BIAcore system depends on both the affinity for the ligand and on the mass of the injected molecule, we used control peptides of the same size as the SU 90-94 peptide: as a positive control, the 5-mer peptide Tuftsin analog (TU-A), and as negative control, a 5-mer peptide corresponding to the C-terminal sequence of VEGF165b, which does not bind to NRP-1.42 Binding to NRP-1 (Figure 5C left panel), but not VEGF-R2 (right panel), was observed for both SU 90-94 and TU-A (curves 1 and 2), whereas the control VEGF165b peptide did not bind (curves 3). Because of the small size of the exon 8–like peptides (5-mer), the binding signals did not permit determination of the affinities for NRP-1. However, this analysis clearly showed that the SU 90-94 and Tuftsin analog directly bind to recombinant NRP-1 in vitro.

We next investigated whether longer SU peptides can also bind to NRP-1. Efficient binding to NRP-1 was observed for both peptide containing the KPxR motif: the SU 81-95 peptide (Figure 5D left panel, curve 1) and, to a lesser extent, the SU 86-100 peptide (curve 2). In contrast, no binding was found for the SU 61-75 peptide, which lacks the motif (curve 3). The binding of the SU 81-95 peptide to NRP-1 was dose-dependent, and no binding of this peptide to either BSA or VEGF-R2 was observed (Figure 5D right panel).

The effect of the peptides on the VEGF165/NRP-1 interaction was also characterized. NRP-1 was injected with or without the peptides on immobilized VEGF165 (Figure 5E). These settings also allowed us to compare the SU 90-94 peptide to the 4-mer peptide Tuftsin because the binding of NRP-1 was measured in these experiments. The association of NRP-1 to VEGF165 was significantly reduced in the presence of SU 90-94, Tuftsin, or TU-A at 100 μM (Figure 5E left panel). A dose-dependent inhibition of the VEGF165/NRP-1 interaction was found for all 3 inhibitory peptides (Figure 5E right panel). The IC50 for Tuftsin and TU-A was similar (20 and 30 μM, respectively) and was only slightly higher for SU 90-94 (50 μM), showing that the SU 90-94 is also a potent inhibitor of VEGF165 binding to NRP-1.

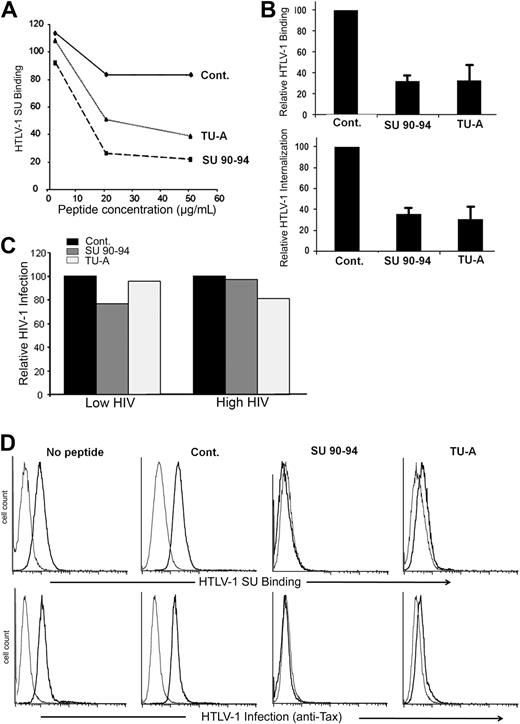

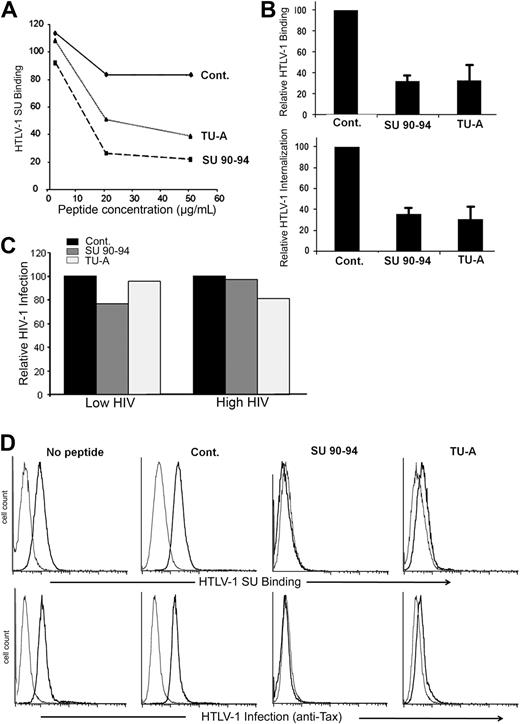

The SU 90-94 or exon 8–like peptides inhibit HTLV-1 entry

To further investigate the property of the exon 8–like motif of the HTLV SU, we examined whether the KPxR-containing peptides block HTLV-1 binding to and infection of target cells. Initially, we preincubated CD4+ T cells with peptides and determined the effect on SU binding. Whereas the control peptide had minimal impact, both SU 90-94 and TU-A reduced SU binding in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6A). The SU 90-94 and TU-A, but not the control peptide, also strongly reduced HTLV-1 virion binding to and internalization into CD4+ T cells (Figure 6B left panel). In contrast, exon 8–like peptides had minimal effect on HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells, even when a low dose of HIV-1 was used (Figure 6C).

The SU 90-94 and exon 8 peptides block HTLV-1 entry into CD4+ T cells or DCs. (A) Effect of the peptides on HTLV-1 SU binding on CD4+ T cells. MOLT4 were incubated in medium alone or in medium containing 2, 20, or 50 μg/mL peptides before incubation with 200 ng/mL HTLV-1 or ASLV SU-rFc. The data show the specific binding (MFISU-rFc–MFISU-ASLV-rFc) normalized on cells incubated with no peptide (100%) and are from 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. (B) Effect of the peptides on HTLV-1 virus binding to or internalization into CD4+ T cells. (Top panel) CD4+ T cells were preincubated with 20 μg/mL peptides, then HTLV-1 virions were added 30 minutes later, and the amount of virus binding was determined as described in “BIAcore binding analysis,” except that 1 μg rather than 5 μg virus was used. (Bottom panel) CD4+ T cells were incubated with 50 μg/mL peptides for 30 minutes. The cells were diluted and incubated with HTLV-1 virions for 3 hours (final concentration, 10 μg/mL peptide), and the amount of virus internalization was determined. HTLV-1 binding and internalization are normalized to the control peptide (100%), and the data are mean ± SD of at least 2 independent experiments. (C) Effect of the peptides on HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were preincubated with 50 ng/mL peptides for 30 minutes, and cells were infected with either a low dose (30 ng/mL) or high dose (80 ng/mL) of HIV-1 virions for 2 hours at 37°C. HIV-1 production was assessed 3 days after infection by measuring the amount of released particles using the anti-CAp24 ELISA. (D) Effect of the peptides on HTLV-1 binding to and infection of MDDCs. (Top panel) Cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL peptides for 30 minutes, exposed to the HTLV-1 SU-rFc (black lines) or the control SU-ASLV-rFc (gray lines), and the level of binding determined. (Bottom panel) Cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL peptides for 30 minutes and infected by cell-free HTLV-1. The extent of infection was determined by flow cytometry at 48 hours after exposure to virus by intracellular staining for the HTLV-1 Tax protein. The black lines represent the staining with Tax-specific antibody; gray lines, the staining with an isotype control.

The SU 90-94 and exon 8 peptides block HTLV-1 entry into CD4+ T cells or DCs. (A) Effect of the peptides on HTLV-1 SU binding on CD4+ T cells. MOLT4 were incubated in medium alone or in medium containing 2, 20, or 50 μg/mL peptides before incubation with 200 ng/mL HTLV-1 or ASLV SU-rFc. The data show the specific binding (MFISU-rFc–MFISU-ASLV-rFc) normalized on cells incubated with no peptide (100%) and are from 1 representative experiment of 2 performed. (B) Effect of the peptides on HTLV-1 virus binding to or internalization into CD4+ T cells. (Top panel) CD4+ T cells were preincubated with 20 μg/mL peptides, then HTLV-1 virions were added 30 minutes later, and the amount of virus binding was determined as described in “BIAcore binding analysis,” except that 1 μg rather than 5 μg virus was used. (Bottom panel) CD4+ T cells were incubated with 50 μg/mL peptides for 30 minutes. The cells were diluted and incubated with HTLV-1 virions for 3 hours (final concentration, 10 μg/mL peptide), and the amount of virus internalization was determined. HTLV-1 binding and internalization are normalized to the control peptide (100%), and the data are mean ± SD of at least 2 independent experiments. (C) Effect of the peptides on HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were preincubated with 50 ng/mL peptides for 30 minutes, and cells were infected with either a low dose (30 ng/mL) or high dose (80 ng/mL) of HIV-1 virions for 2 hours at 37°C. HIV-1 production was assessed 3 days after infection by measuring the amount of released particles using the anti-CAp24 ELISA. (D) Effect of the peptides on HTLV-1 binding to and infection of MDDCs. (Top panel) Cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL peptides for 30 minutes, exposed to the HTLV-1 SU-rFc (black lines) or the control SU-ASLV-rFc (gray lines), and the level of binding determined. (Bottom panel) Cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL peptides for 30 minutes and infected by cell-free HTLV-1. The extent of infection was determined by flow cytometry at 48 hours after exposure to virus by intracellular staining for the HTLV-1 Tax protein. The black lines represent the staining with Tax-specific antibody; gray lines, the staining with an isotype control.

We also evaluated the effect of the peptides on HTLV-1 interactions with DCs. The SU 90-94 and TU-A peptides dramatically reduced the binding of the HTLV-1 SU to DCs as well as HTLV-1 infection of DCs, whereas the control peptide did not (Figure 6D). The amount of the viral protein Tax, which can be detected in cells only after proviral de novo production of viral proteins, was reduced to below the level of detection for SU 90-94 and at almost control level for TU-A (Figure 6D bottom panel). These analyses clearly demonstrate that the KPxR motif of the HTLV-1 SU is a receptor binding domain and extend the importance of NRP-1 to cell-free HTLV-1 infection of primary DCs.

Discussion

Although recent studies have independently identified GLUT1, HSPGs, and NRP-1 as key players in HTLV-1 entry, the specific roles of each of these molecules in this process have not been well characterized. The work presented here was aimed at clarifying the respective contribution of HSPGs and NRP-1 during HTLV-1 binding, entry, and infection.

Among other physiologic roles, NRP-1 functions as a receptor for VEGF165. Using the new model of HTLV-1 infection involving primary DCs and cell-free virus, we first demonstrated that VEGF165 is a specific and potent inhibitor of HTLV-1 infection. It was previously reported that, like VEGF165, the HTLV-1 SU binds to HSPGs14 as well as to NRP-1.12 However, it was unclear whether HSPG and NRP-1 function together, as during VEGF165 signaling, or individually. Here we report that (1) binding of HTLV-1 to the cell surface requires the b domain of NRP-1; (2) HSPGs enhance the formation of complexes between HTLV-1 Env and the NRP-1 ectodomain; and (3) binding of the HTLV-1 SU to target cells is partially blocked by the domain of VEGF165, which mediates the HSPG-dependent interaction with NRP-1. These findings reveal that HSPGs and NRP-1 also cooperate during HTLV-1 SU binding, providing the functional explanation for the previously demonstrated critical importance of these 2 molecules during HTLV-1 entry.

VEGF165 also contains residues located in the exon 8 domain that mediate interaction with NRP-1 in a heparin-independent manner.23 Using sequence comparisons and in vitro binding experiments, we identified a VEGF165 exon 8–like motif in the HTLV-1 SU (amino acids [aa] 90-94: KPxR) and demonstrated that this sequence mediates direct binding to NRP-1 and competes with VEGF165 for NRP-1 binding. Because of technical limitations, we were unable to produce sufficient quantities of the HTLV-1 SU to study the direct SU/NRP-1 interaction. However, we demonstrated that 15-mer SU peptides containing the KPxR motif could also bind to NRP-1. The aa 90-94 motif is in an internal position in the SU, whereas the exon 8 sequence constitutes the C-terminus of VEGF165. This could explain why the SU 81-95 peptide, which contains only a single residue after the motif, has higher affinity for NRP-1 than the SU 86-100 peptide, in which the motif is in an internal position. We further demonstrated that both exon 8 peptides and the SU 90-94 peptides block HTLV-1 binding, entry, and infection in assays using the primary target cells of this virus (CD4+ T cells and DCs). No inhibition was found when HIV-1 was used as a control virus, showing that the peptides selectively impact HTLV-1 entry. These findings confirm both the importance of the exon 8 domain in NRP-1 binding and the key role of NRP-1 in HTLV-1 entry.

Because the SU KPxR motif is involved in HTLV-1 entry, one would expect that it would correspond to an exposed and neutralizing region. Indeed, antibodies raised against the aa 89-107 of the HTLV-1 SU recognize the native form of the SU, suggesting that this region is indeed exposed on the surface of the protein.43 Furthermore, the SU 89-107 region, containing the KPxR motif, has been characterized as neutralizing epitope,43,44 and the corresponding antibodies were shown to preferentially recognize the (KKPNRN) sequence.43 In addition, we previously demonstrated that the residue R94 in SU, the arginine residue in the KPxR motif, was essential for HTLV-1 infectivity.31 Our data thus clarify the previous data showing the importance of the SU 89-107, by revealing that this region is indeed a receptor-binding domain.

For VEGF165, blocking either the exon 7– or exon 8–mediated interactions is sufficient to prevent binding to NRP-1.23,25 We show here that both the exon 7 and exon 8 peptides can block HTLV-1 entry. These observations indicate that HTLV-1 entry is also governed by both HSPG-mediated and direct interactions between the SU and NRP-1, in a cooperative manner. The initial interactions of VEGF165 with HSPG/NRP-1 complexes permit the subsequent presentation of VEGF165 to VEGF-R2, thereby forming the stable complex competent for signal transduction. This is reflected by the ability of VEGF165 to bridge NRP-1 and VEGF-R2.45 Strikingly, we previously found that the HTLV-1 SU is able to bridge NRP-1 and GLUT1.12 These observations strongly suggest that the formation of the HTLV-1 entry receptor complex mirrors the formation of the HSPG/NRP-1/VEGF-R2 complex. We therefore envision a model in which NRP-1 functions as an intermediate that recruits HTLV-1 particles clustered on HSPGs and present them to GLUT1, forming an HSPG/NRP-1/GLUT1 binding structure that renders Env competent for fusion. Alternatively, the stable binding of the SU to NRP-1 could trigger conformational changes in the SU, favoring its subsequent interaction with GLUT1, a receptor/coreceptor model reminiscent of what occurs during HIV entry. In both models, GLUT1 functions as a postbinding receptor, in agreement with observations that GLUT1 overexpression increases HTLV-1 Env-mediated fusion or infection but not HTLV-1 virus binding.7,10

In conclusion, our study provides a model for HTLV-1 entry that reconciles and extends the previous observations concerning HSPGs, NRP-1, and GLUT1. Moreover, the molecular mimicry we demonstrated opens new perspectives for the understanding of HTLV-1 propagation in vivo. In contrast to T cells, which spontaneously produce VEGF165,46 VEGF165 production by DCs is restricted to certain stimulation conditions.35 It could therefore be speculated that this lack of VEGF165 production accounts, at least in part, for the particular susceptibility of DCs to cell-free HTLV-1 infection. More generally, we propose that HTLV-1 tropism is governed by a subtle balance between the levels of HSPGs and NRP-1 at the cell surface and the amount of extracellular NRP-1 ligands, especially VEGF165. Future elucidation of these complex interactions would greatly improve the understanding of HTLV-1 transmission and pave the way for the design of novel therapeutic strategies against HTLV-1 infection.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Strazec, C. Vander Kooi, and M. Crépin for helpful discussions and D. C. Bertolette and M. Chazal for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), Center for Cancer Research; Association de Recherche contre le Cancer (no. 3123) or Sang pour Cent la Vie; the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Immune and Viral Diseases Program of the Sainte Justine Research Center (Montreal, QC); and, in whole or in part, by the NCI, NIH (contract no. N01-CO-12400). S.L. was the recipient of grants from the French Ministry of Research and Association de Recherche contre le Cancer.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: S.L., M.B., R.V., C.P.-S., and S.J. performed research experiments and analyzed the data; M.S. performed sequence comparisons; G.P. and F.W.R. contributed to the experimental design and provided vital new reagents; N.H. contributed vital new reagents and wrote the paper; K.S.J. contributed to the experimental design, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the paper; and C.P. designed the research project, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Claudine Pique, Institut Cochin, 22 rue Mechain, 75014 Paris, France; e-mail: claudine.pique@inserm.fr; or Kathryn S. Jones, NCI-Frederick, SAIC-Frederick, Bldg 567, Rm 253, Frederick, MD 21702; e-mail: joneska@mail.nih.gov.

References

Author notes

*S.L. and M.B. contributed equally to this work.

†K.S.J. and C.P. contributed equally to this work, and both are last authors.