Abstract

Platelet activating factor (PAF) and PAF-like lipids induce inflammatory responses in target cells. These lipid mediators are inactivated by PAF-acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH). The PAF signaling system affects the growth of hematopoietic CD34+ cells, but roles for PAF-AH in this process are unknown. Here, we investigated PAF-AH function during megakaryopoiesis and found that human CD34+ cells accumulate this enzymatic activity as they differentiate toward megakaryocytes, consistent with the expression of mRNA and protein for the plasma PAF-AH isoform. Inhibition of endogenous PAF-AH activity in differentiated megakaryocytes increased formation of lipid mediators that signaled the PAF receptor (PAFR) in fully differentiated human cells such as neutrophils, as well as megakaryocytes themselves. PAF-AH also controlled megakaryocyte αIIbβ3-dependent adhesion, cell spreading, and mobility that relied on signaling through the PAFR. Together these data suggest that megakaryocytes generate PAF-AH to modulate the accumulation of intracellular phospholipid mediators that may detrimentally affect megakaryocyte development and function.

Introduction

Platelet activating factor (PAF) is an inflammatory phospholipid that regulates activation of platelets, neutrophils, and other cells of the innate immune system.1,2 Activation of these cells by PAF occurs through a well-characterized receptor, PAF receptor-1 (PAFR-1). This receptor recognizes the short sn-2 acetyl residue of PAF,1,2 but this interaction is not fully specific allowing other oxidatively modified phospholipids with short sn-2 residues to stimulate cells via PAFR-1. Because these modified phospholipids signal through PAFR-1, they are referred to as PAF-like lipids.3 Both PAF and PAF-like lipids are substrates of a small subset of phospholipases A2, the PAF-acetylhydrolases (PAF-AHs), which quench signaling by both types of PAFR ligands.4

Although the PAF signaling system has been studied extensively in endothelial cells and circulating leukocytes, platelets, and other human cells,2,4-7 its roles in the bone marrow compartment are less characterized. PAF is present in human bone marrow where it regulates the function of stem cell progenitors.8 Human bone marrow cells express PAFR-1 transcripts,9 and PAF modulates DNA synthesis in guinea pig and human bone marrow cells.10,11 Several lipid mediators affect the marrow cytokine network.12-14 Concerning PAF, it was reported to stimulate macrophage colony-stimulating factor and prolactin secretion from bone marrow stromal cells,15,16 suggesting its role in regulating myelopoiesis and erythropoiesis. Consistent with these observations Dupuis et al17 reported that PAF directly affects the growth of human myeloid and erythroid progenitors. CD34+ cells differentiated into megakaryocytes also respond to PAF.18

As a counterweight to PAFR activation, PAF-AH appears to be critical for human stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Four different isoforms of PAF-AH can process PAF in humans: the plasma isoform circulates in association with lipoproteins and is intracellular in some cell types, type 2 PAF-AH (PAF-AH2) that is exclusively intracellular, type 1b2 (PAF-AH1b2), and type 1b3 (PAF-AH1b3).6,19 Plasma PAF-AH and PAF-AH2 share significant homology and specificity in that both isoforms cleave PAF and PAF-like lipids with short alkyl sn-2 residues.6 PAF-AH1b2 and PAF-AH1b3 specifically process PAF.6 Allogeneic bone marrow transplantations in the Japanese population, where a genetic polymorphism in the plasma PAF-AH gene (PLA2G7) is observed at a frequency of 4%,20 suggest that hematopoietic stem cells rather than hepatocytes may be the primary source of PAF-AH activity.21 Although the cellular sources of PAF-AH in the bone marrow have not been established, stromal, mononuclear, and mast cells metabolize exogenous PAF.22-24

Here we show that human CD34+ cells generate PAF-AH activity as they differentiate into megakaryocytes and that this activity correlates with an up-regulation of plasma PAF-AH message and protein. We also demonstrate that increased PAF-AH activity regulates megakaryocyte adhesion and spreading by preventing the accumulation of lipid mediators that signal through the PAFR. These studies identify new facets of megakaryocyte biology and highlight the importance of signaling via the PAFR during human megakaryopoiesis.

Methods

Cell isolation, differentiation, and nomenclature

Human CD34+ cells from human umbilical cord blood were isolated as described previously.25-27 The CD34+ cells were placed in X-Vivo 20 media that contained 40 ng/mL recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 50 ng/mL recombinant thrombopoietin (TPO; Invitrogen), and 10 ng/mL recombinant human interleukin-3 (IL-3; Invitrogen). The cells were harvested every 2 to 3 days and resuspended in media with fresh growth factors, with the exception that IL-3 was removed at day 5. Unless otherwise indicated, the cells at culture day 13 were placed on immobilized human fibrinogen (EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes. In other studies referred to in the text, megakaryocytes were left in suspension culture, adhered to collagen, vitronectin, or laminin, or sorted with CD61+ beads before analysis. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Utah and participant informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Freshly isolated CD34+ cells and cells at culture day 7 or 13 were used for all of the studies. Cells at culture day 0 are referred to as CD34+ cells. Cells at culture day 7 are referred to as megakaryocyte precursors. Cells at culture day 13, which lacked CD34 but expressed αIIb integrins and other critical platelet biomarkers,25-27 are referred to as megakaryocytes.

Immunofluorescence

Proliferating and differentiating CD34+ cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells in suspension were centrifuged at 63g onto Vectabond (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA)–coated coverslips using a Cytospin 2 centrifuge (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA). For adherent studies, the cells were placed in 8-well chamber coverslides (Nunc, Rochester, NY) that were coated with fibrinogen. After the fixation step, the cells were washed, permeabilized, and immunostained as previously described.25-30 The cells were viewed by confocal microscopy using a 60×/1.42 NA oil objective on an FV300 Olympus IX81 microscope (Melville, NY), with PMT values adjusted to no signal with IgG controls. The following antibodies, peptides, and recombinant proteins were used for these studies: anti–integrin αIIb (sc-15328), anti–plasma PAF-AH (sc-16952), and corresponding blocking peptide from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti–β-tubulin (T5293) from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO); anti–PAF-AH1b2 (ab15875) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); recombinant human PAF-AH1b2 (G22423F) from Genway (San Diego, CA); and goat anti–mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and anti–rabbit Alexa Fluor 546 from Invitrogen.

PAF biosynthesis and PAF-AH activity assays

PAF synthesis assays were performed with megakaryocytes using procedures previously described for endothelial cells.31 For the PAF-AH activity assays, the cells were cultured for indicated times and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 500g in a tabletop centrifuge, and the supernatants were removed. Cells were lysed in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.8) with 16 mM CHAPS, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM benzamidine hydrochloride, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 10 μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, and corresponding supernatants from intact cells were concentrated using 30000 Da MWCO spin filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA). PAF-AH activity assays were carried out as previously described with minor modifications.32 Briefly, the enzyme source was incubated with 80 μM substrate consisting of a mixture of unlabeled PAF and [3H-acetyl]-PAF (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for 15 minutes at 37°C, in the presence of DTT and EDTA. The specific radioactivity of the substrate was approximately 20000 dpm/nmol PAF. The reactions were quenched with glacial acetic acid (10 M) and excess sodium acetate (0.1 M). Cleaved [3H]acetate was isolated using Bakerbond spe Octadecyl (C18) extraction columns (Mallinckrodt Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ). Protein in the cell lysates was normalized by Bradford assay.33

qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated from megakaryocytes at various stages of differentiation with TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed using the Superscript III first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen), and the cDNA was used in a quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) reaction using the PerfeCTa SYBR green supermix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) on a Bio-Rad iCycler machine (Hercules, CA). Primers specific for mRNA in the qRT-PCR reaction were as follows: β-actin, 5′-GCTCGTCGTCGACAACGGCTC and 5′-CAAACATGATCTGGGTCATCTTCTC; plasma PAF-AH, 5′-GGGGCATTCAGGACACTTTA and 5′-TTCATCACCCAGTGGAAACA; PAF-AH2, 5′-TGCCAGTCACAAAAGCAAAG and 5′-TGAGGAAGGGGAGAAGGAAT; PAFAH1b1, 5′-ATGGGTCGTAGCAACAAAGG and 5′-GACATAGGGTGCCGTCTTGT; PAFAH1b2, 5′-CTGTTCGTGGGAGACTCCAT and 5′-ATAGCCCCCTCCTGTCAGAT; PAFAH1b3, 5′-AGGGTCGGCATCTAGGAAGT and 5′-CGTGGCTGACAGCAAAGATA; PAFR Tr1 (PAFR-1), 5′-CTGCCCTTCTCGTAATGCTC and 5′-GGCTGGGGCCAGGACCCAGA; and PAFR Tr2 (PAFR-2), 5′-CTGCCCTTCTCGTAATGCTC and 5′-CCTGAGCTCCCCGAGAAGTCA. Message levels were normalized to β-actin and quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT method.34

Calcium release assays

To measure calcium fluxes, megakaryocytes were counted, resuspended in HBSS, and loaded with 1 μM fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. After this incubation period, cells were washed and resuspended at a concentration of 4 × 106 megakaryocytes/mL. The megakaryocytes were pretreated with vehicle (Hanks balanced salt solution + 1% endotoxin free human serum albumin [HBSS-A]; Baxter Healthcare, Vienna, Austria) or 10 μM WEB 2086 (ethanol stock dried under nitrogen then resuspended in HBSS-A; Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany), a PAFR blocker,35 for 15 minutes. The megakaryocytes were subsequently stimulated with C16 carbamyl-PAF (also referred to as cPAF), a biologically active PAF analog that is resistant to PAF-AH hydrolysis, or C16 Lyso-PAF (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA). All lipids were stored in ethanol. Aliquots of the lipids were removed before experiments, dried under nitrogen, and resuspended in HBSS with 1% human serum albumin (HBSS/A). Mean peak fluorescence was measured in a Synergy HT fluorimeter (BioTek, Winooski, VT) using a 488-nm excitation, 20-nm bandwidth filter and a 528-nm emission, 20-nm bandwidth filter.

Calcium fluxes were also measured in polymorphonuclear (PMN) as reported previously.36 For these studies, phospholipids were extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer37 from megakaryocytes that were treated with a nontoxic concentration38-40 of Pefabloc SC (100 μM; Boehringer-Ingelheim) to irreversibly inhibit PAF-AH activity.40 In select studies, phospholipids isolated from Pefabloc-treated megakaryocytes were digested with 10 μg recombinant plasma PAF-AH (ICOS, Bothell, WA) for 3 hours at 37°C and then added to PMNs to test whether the lipids that stimulated calcium release were short-chained phospholipid agonists. In additional experiments, PMNs were pretreated with the PAFR blocker (ie, WEB 2086) before incubation with phospholipids isolated from Pefabloc-treated megakaryocytes.

Megakaryocyte adherence and spreading, and αIIbβ3 activation

Differentiated megakaryocytes were pretreated with a PAFR blocker (ie, WEB 2086) or vehicle and placed on immobilized fibrinogen for 5, 15, or 30 minutes in the presence of cPAF or its vehicle (HBSS/A). At the end of the each time point, the cells were gently washed with warm media and fixed, and 5 independent fields were counted. In parallel, the cells were stained with an antibody against β-tubulin and the number of spread cells per field (> 30 μm) were determined. In selected studies, endogenous PAF-AH activity was quenched with 100 μM Pefabloc, and cell adherence and spreading were measured. For studies using thrombin, megakaryocytes were activated with 0.5 U/mL final concentration of thrombin (Sigma-Aldrich) in place of cPAF.

Flow cytometry for plasma membrane αIIbβ3 was conducted as previously described.28 The activated form of αIIbβ3 was measured using PAC-1 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), an antibody that recognizes changes in the conformation of αIIbβ3 integrin,28,41 and by soluble Alexa 488–conjugated fibrinogen (Invitrogen). These studies were done in CD41a-PE (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA)–stained differentiated megakaryocytes that were treated with a PAFR blocker (WEB 2086) or not, then with cPAF, its vehicle (HBSS/A), or thrombin for 5 minutes in the presence of PAC-1 or Alexa 488–conjugated fibrinogen. Samples were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by flow within 24 hours on a FACScan (BD Biosciences) analyzer. Staining specificity for PAC-1 was confirmed using an RGDS peptide (Sigma-Aldrich).

Megakaryocyte mobility assay

Day-13 megakaryocytes were counted and 0.5 × 106 cells (pretreated with a PAFR blocker [ie, WEB 2086] or vehicle for 30 minutes at 37°C) were placed in duplicate in the upper chamber of a 5-μm pore Transwell filter in a 24-well tissue culture–treated plate (Costar, Corning, NY). The lower chamber, coated with fibrinogen as described previously, was filled with X-vivo media containing either 10 nM cPAF or vehicle (HBSS/A). Cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C in a humid, 5% CO2 incubator. Upper and lower chambers were washed with HBSS, and cells were treated with 1 × Cell Dissociation Solution (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 2 μg/mL calcein AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Aliquots of cell suspension were measured by fluorimeter (488-nm excitation, 20-nm bandwidth; 528-nm emission, 20-nm bandwidth) in triplicate and compared with a standard curve of calcein AM–stained megakaryocytes. Cell numbers were calculated through linear regression analysis and the resulting values were used to generate fold increase of mobility compared with vehicle.

Statistical analyses

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to identify differences that existed among multiple experimental groups. If significant differences were found, a Tukey test was used to determine the location of difference. For all of the analyses, P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

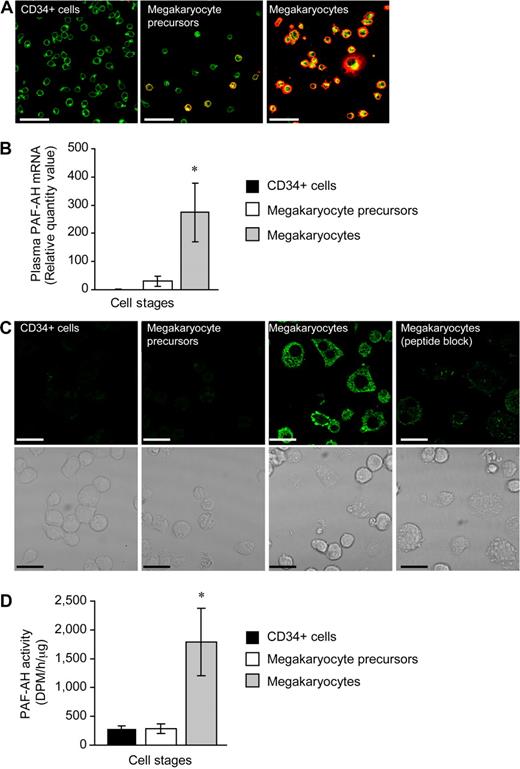

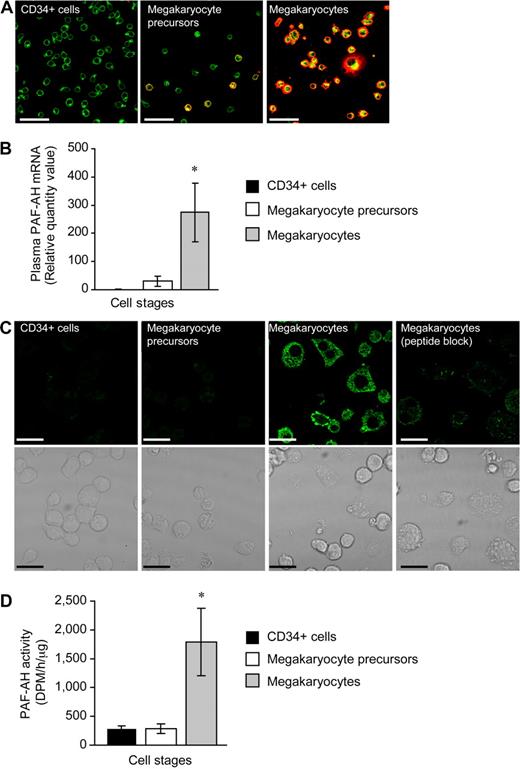

Megakaryocytes generate PAF-AH

We examined PAF-AH expression during megakaryopoiesis using a human CD34+ model system previously described by our group.25-27 Undifferentiated CD34+ cells did not possess the platelet-specific biomarker integrin αIIb (Figure 1A left panel) and expressed very low levels of mRNA for plasma PAF-AH (Figure 1B and data not shown). mRNA for plasma PAF-AH increased slightly but remained low at culture day 7 (Figure 1B) and a subset of the cells (referred to as megakaryocyte precursors) began to express αIIb integrins (Figure 1A middle panel). However, plasma PAF-AH mRNA levels were markedly increased (Figure 1B) in differentiated cells (ie, culture day 13; referred to as megakaryocytes) that no longer expressed CD34 (data not shown) but did express αIIb integrins (Figure 1A far right panel) and displayed other megakaryocyte-like features as previously described.25-27 Protein for plasma PAF-AH protein was absent in CD34+ cells and megakaryocyte precursors but was expressed by megakaryocytes (Figure 1C). Specificity for the PAF-AH antibody was demonstrated by the marked reduction in megakaryocyte staining when the peptide immunogen was present (Figure 1C far right panel). Similar to mRNA and protein for plasma PAF-AH, intracellular PAF-AH activity accumulated in megakaryocytes whether they were left in suspension culture (data not shown) or adhered to immobilized fibrinogen (Figure 1D). Although megakaryocytes released low amounts of PAF-AH into the extracellular milieu (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), these amounts are very small compared with PAF-AH secreted by macrophages,42 and thrombin did not increase PAF-AH secretion (277 + 139 vs 278 + 85 dpm/h per microliter, vehicle vs thrombin, respectively). Undifferentiated CD34+ cells expressed low levels of mRNA for the other PAF-AH isoforms (PAF-AH2, PAF-AH1b2, and PAF-AH1b3) and PAF-AH1b1, the common beta regulatory subunit of PAF-AH1b2 and PAF-AH1b3 (data not shown and Table 1). Unlike plasma PAF-AH, however, none of the transcript levels appreciably increased during megakaryocyte differentiation (Table 1). Protein expression for PAF-AH1b2 was confirmed in megakaryocyte precursors and megakaryocytes (Figure S2A,B).

Hematopoietic CD34+ cells differentiated into megakaryocytes accumulate PAF-AH activity. Freshly isolated CD34+ cells (culture day 0), megakaryocyte precursors (culture day 7), or megakaryocytes (culture day 13) adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were used for panels A through D. (A) Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green) and integrin αIIb (red) localization; representative of more than 10 independent experiments. Scale bar represents 50 μm. (B) Plasma PAF-AH mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR and relative values of megakaryocyte precursors and megakaryocytes, normalized to β-actin, were compared with culture day 0 (CD34+ cells). The bars are the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with freshly isolated CD34+ cells or megakaryocyte precursors. (C) Plasma PAF-AH localization in megakaryocytes. Results are representative of 3 experiments. (D) PAF-AH activity in cell lysates. The bars in this graph represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with freshly isolated CD34+ cells or megakaryocyte precursors.

Hematopoietic CD34+ cells differentiated into megakaryocytes accumulate PAF-AH activity. Freshly isolated CD34+ cells (culture day 0), megakaryocyte precursors (culture day 7), or megakaryocytes (culture day 13) adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were used for panels A through D. (A) Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green) and integrin αIIb (red) localization; representative of more than 10 independent experiments. Scale bar represents 50 μm. (B) Plasma PAF-AH mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR and relative values of megakaryocyte precursors and megakaryocytes, normalized to β-actin, were compared with culture day 0 (CD34+ cells). The bars are the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with freshly isolated CD34+ cells or megakaryocyte precursors. (C) Plasma PAF-AH localization in megakaryocytes. Results are representative of 3 experiments. (D) PAF-AH activity in cell lysates. The bars in this graph represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with freshly isolated CD34+ cells or megakaryocyte precursors.

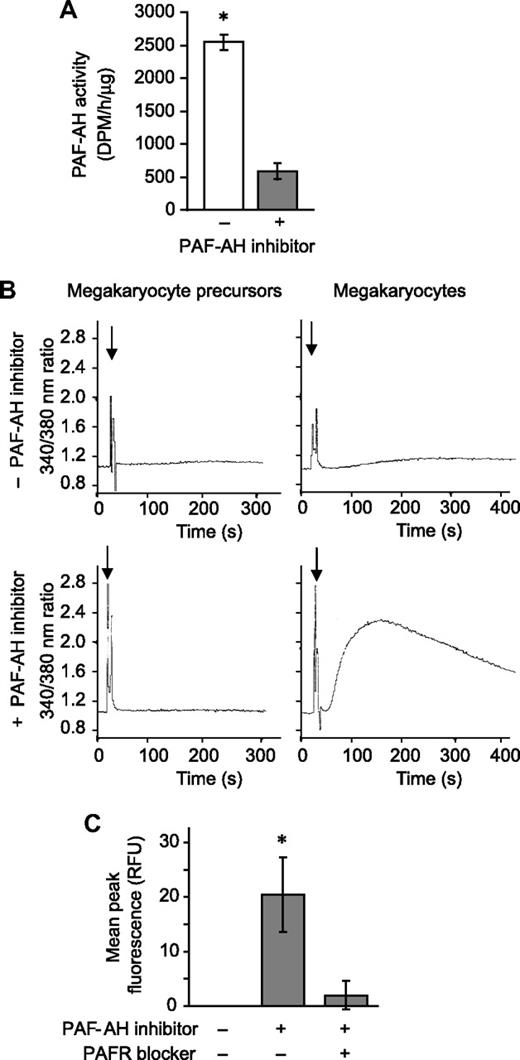

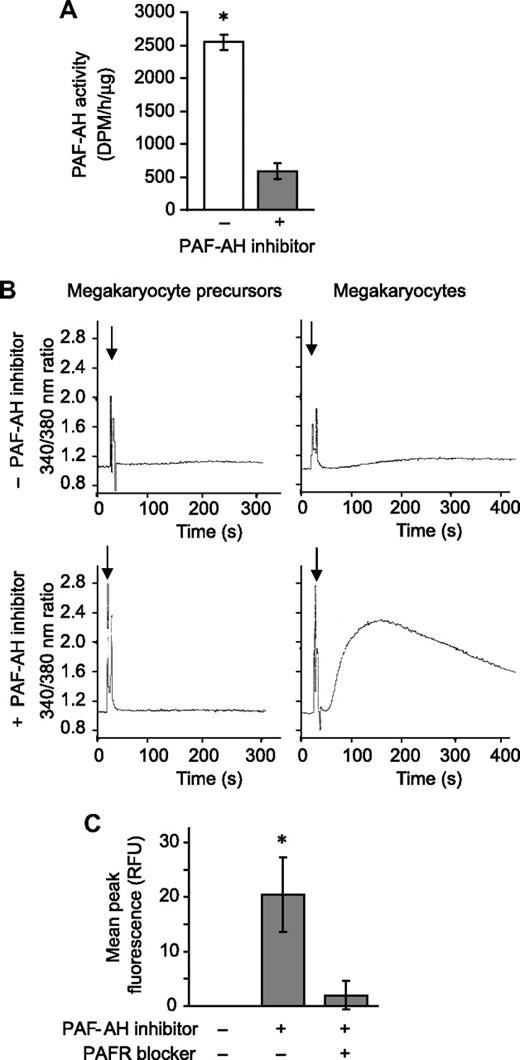

PAF-AH prevents megakaryocytes from accumulating phospholipids that signal through the PAFR

Next we determined whether PAFR agonists accumulate when endogenous PAF-AH activity was neutralized. Megakaryocytes were pretreated with Pefabloc SC, an irreversible PAF-AH inhibitor that does not induce cell toxicity as measured by trypan blue exclusion38-40 (and data not shown), and as expected endogenous PAF-AH activity was greatly reduced (Figure 2A). In separate studies, phospholipids were extracted from megakaryocytes and the reconstituted lipids were added to polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), blood cells that have a well-characterized PAFR signaling system.4 Phospholipids from megakaryocyte precursors, extracted after Pefabloc or vehicle treatment, did not initiate calcium fluxes in PMNs (Figure 2B left panels). Likewise, phospholipids extracted from vehicle- or thrombin-treated megakaryocytes (ie, culture day 13) did not induce calcium fluxes (Figure 2B top right panel and data not shown). However, inhibition of endogenous PAF-AH activity by Pefabloc SC was associated with a rapid accumulation of bioactive phospholipids in megakaryocytes that signaled calcium fluxes in target PMNs (Figure 2B bottom right panel). PAF synthesis assays demonstrated that the bioactive phospholipids were not authentic PAFs (data not shown). However, the addition of recombinant PAF-AH to the extracted phospholipids or pretreatment of the PMNs with a PAFR blocker eliminated this signaling response (Figure S3), indicating that the species inducing the signaling response is a PAF-like lipid. Also consistent with this conclusion is that treatment of the extracted phospholipids with phospholipase A1, which hydrolyzes diacyl phospholipids but not alkyl phospholipids, did not prevent megakaryocyte-derived phospholipids from inducing a calcium flux in PMNs (inhibition < 5%, data not shown).

Endogenous PAF-AH activity prevents megakaryocytes from accumulating phospholipids that activate the PAFR. (A) Intracellular PAF-AH activity (cell lysate) was measured as previously described32 in megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen in the presence or absence of 100 μM Pefabloc SC (PAF-AH inhibitor). The bars represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. (B) Megakaryocyte precursors (left column) or megakaryocytes (right column) were treated with vehicle (top row) or 100 μM of the PAF-AH inhibitor Pefabloc (bottom row). Phospholipids were extracted and added ( ) to Fura-2 AM–loaded human PMNs to measure intracellular calcium release by fluorometry. This figure is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were loaded with Fluo-4 AM in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker, WEB 2086 (10 μM). The cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or 100 μM Pefabloc (PAF-AH inhibitor) to quench endogenous PAF-AH activity, and intracellular calcium fluxes were measured and are presented as mean peak fluorescence. The bars in panels A and C represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * in panels A and C indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with untreated or other treatment groups.

) to Fura-2 AM–loaded human PMNs to measure intracellular calcium release by fluorometry. This figure is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were loaded with Fluo-4 AM in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker, WEB 2086 (10 μM). The cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or 100 μM Pefabloc (PAF-AH inhibitor) to quench endogenous PAF-AH activity, and intracellular calcium fluxes were measured and are presented as mean peak fluorescence. The bars in panels A and C represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * in panels A and C indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with untreated or other treatment groups.

Endogenous PAF-AH activity prevents megakaryocytes from accumulating phospholipids that activate the PAFR. (A) Intracellular PAF-AH activity (cell lysate) was measured as previously described32 in megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen in the presence or absence of 100 μM Pefabloc SC (PAF-AH inhibitor). The bars represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. (B) Megakaryocyte precursors (left column) or megakaryocytes (right column) were treated with vehicle (top row) or 100 μM of the PAF-AH inhibitor Pefabloc (bottom row). Phospholipids were extracted and added ( ) to Fura-2 AM–loaded human PMNs to measure intracellular calcium release by fluorometry. This figure is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were loaded with Fluo-4 AM in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker, WEB 2086 (10 μM). The cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or 100 μM Pefabloc (PAF-AH inhibitor) to quench endogenous PAF-AH activity, and intracellular calcium fluxes were measured and are presented as mean peak fluorescence. The bars in panels A and C represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * in panels A and C indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with untreated or other treatment groups.

) to Fura-2 AM–loaded human PMNs to measure intracellular calcium release by fluorometry. This figure is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were loaded with Fluo-4 AM in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker, WEB 2086 (10 μM). The cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or 100 μM Pefabloc (PAF-AH inhibitor) to quench endogenous PAF-AH activity, and intracellular calcium fluxes were measured and are presented as mean peak fluorescence. The bars in panels A and C represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * in panels A and C indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with untreated or other treatment groups.

We next determined whether megakaryocytes, which express mRNA for PAFR-1 but not PAFR-2 (data not shown; Table 2; Figure S4), respond to a stable PAFR agonist. cPAF, a nonhydrolyzable analog of PAF, but not inactive Lyso-PAF, induced calcium fluxes in megakaryocytes, a response that was blocked by a PAFR blocker (Figure S5). Blockade of the PAFR also prevented calcium fluxes generated by endogenous PAF-like lipids extracted from megakaryocytes (Figure 2C).

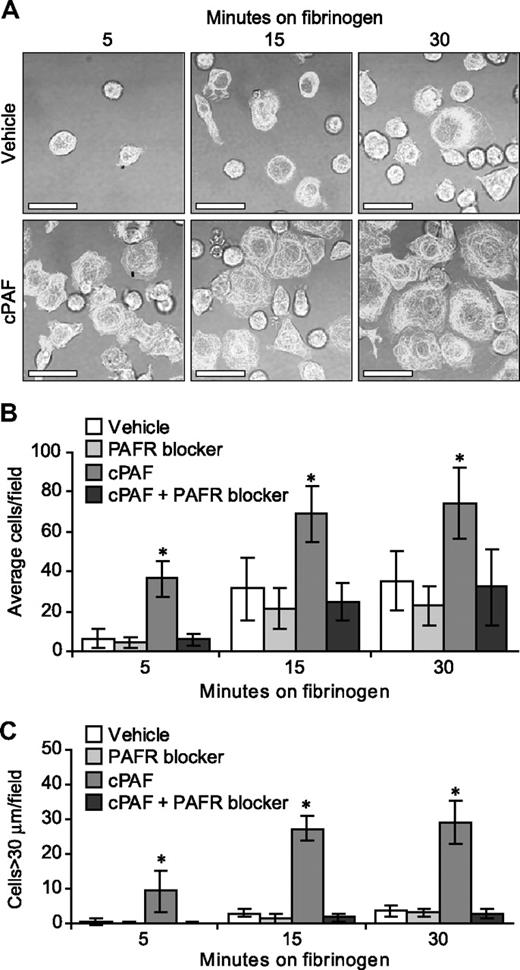

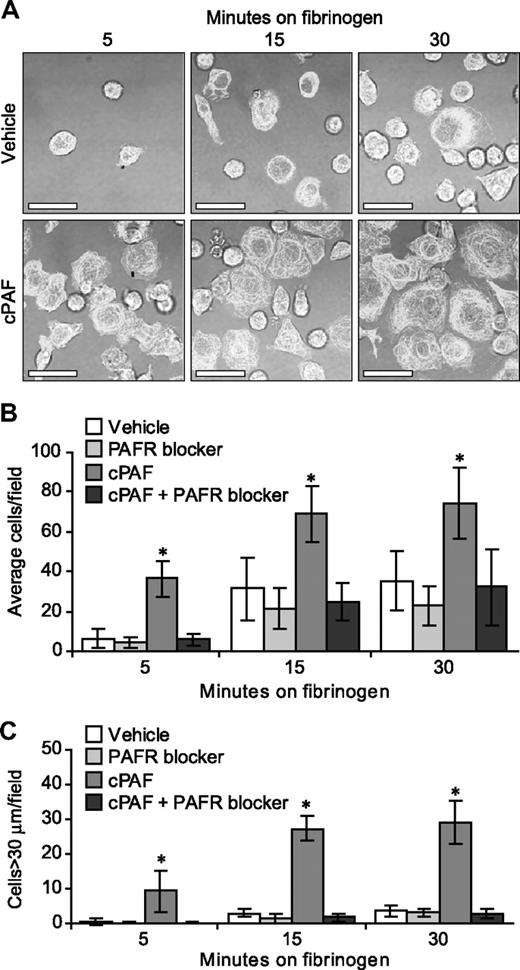

Signaling through the PAFR regulates αIIbβ3-dependent megakaryocyte adherence and spreading

In the human megakaryocyte model system used for these studies, the majority (> 90%) of differentiated cells at culture day 13 express αIIb and β3 integrins, β-tubulin, and P-selectin25-27 (and data not shown). The expression of αIIb integrins, however, varies in intensity and cellular distribution (ie, intracellular versus surface) in megakaryocytes and, as a result, the degree of basal adherence to immobilized fibrinogen and subsequent spreading varies from culture to culture (J.M.F., unpublished observations, 2007). Therefore, we asked whether signals delivered through the PAFR enhance adherence and spreading in megakaryocytes over basal levels. cPAF significantly increased adherence of megakaryocytes to immobilized fibrinogen (Figure 3A). Adherence was abrogated by preincubation of the megakaryocytes with a PAFR blocker (Figure 3B) or an αIIbβ3 receptor antagonist (data not shown). cPAF also increased cell spreading on immobilized fibrinogen (Figure 3A,C) and pretreatment of the cells with a PAFR blocker negated spreading induced by cPAF-stimulated (Figure 3C), but not thrombin-stimulated (Figure S6), megakaryocytes.

Stimulation of the PAFR increases the rate of megakaryocyte adhesion and spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. (A) Megakaryocytes were placed on immobilized fibrinogen for the designated times in the presence of 10 nM cPAF (bottom row), a stable PAF analog, or its vehicle (top row). β-Tubulin (white stain) was localized in the differentiated megakaryocytes. Scale bar represents 30 μm. (B-C) Megakaryocytes were pretreated with or without the PAFR blocker WEB 2086 (10 μM), and the cells were subsequently placed on immobilized fibrinogen in the presence of cPAF or its vehicle. The number of adherent megakaryocytes (B) or megakaryocytes with diameters greater than 30 μm (C) was determined for each time point. The figure is representative of 5 independent experiments. The bars in panels B and C represent the mean ± SD, and * identifies statistical significance (P < .05) between the treatment groups.

Stimulation of the PAFR increases the rate of megakaryocyte adhesion and spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. (A) Megakaryocytes were placed on immobilized fibrinogen for the designated times in the presence of 10 nM cPAF (bottom row), a stable PAF analog, or its vehicle (top row). β-Tubulin (white stain) was localized in the differentiated megakaryocytes. Scale bar represents 30 μm. (B-C) Megakaryocytes were pretreated with or without the PAFR blocker WEB 2086 (10 μM), and the cells were subsequently placed on immobilized fibrinogen in the presence of cPAF or its vehicle. The number of adherent megakaryocytes (B) or megakaryocytes with diameters greater than 30 μm (C) was determined for each time point. The figure is representative of 5 independent experiments. The bars in panels B and C represent the mean ± SD, and * identifies statistical significance (P < .05) between the treatment groups.

Because inhibition of endogenous PAF-AH in megakaryocytes led to an accumulation of PAF-like lipids (Figure 2), we tested whether inhibition of endogenous PAF-AH induced cell spreading that was similar to cPAF. Inhibition of PAF-AH with Pefabloc, but not its inactive analog (AEBSNH2), enhanced spreading of megakaryocytes on immobilized fibrinogen, a response that was inhibited by a PAFR blocker (Figure S7).

Next we examined whether cPAF induced migration of megakaryocytes. cPAF significantly induced movement of megakaryocytes through a 5-μm pore compared with its vehicle, and pretreatment of the cells with a PAFR blocker inhibited this response (Figure S8).

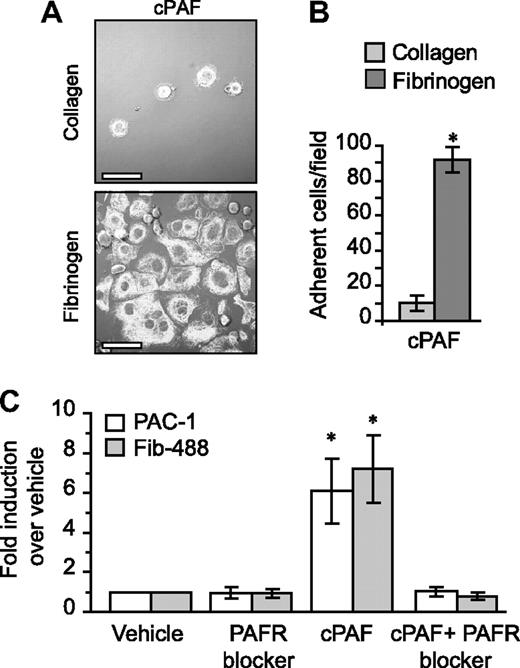

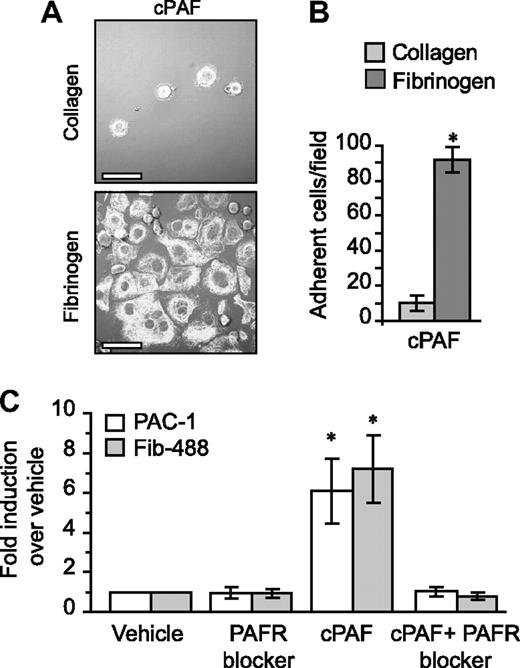

Unlike fibrinogen, adherence to immobilized collagen—which delivers signals independent of αIIbβ3—was minimal in the presence of cPAF (Figure 4A-B). Similarly, cPAF did not increase adherence of megakaryocytes to laminin, where basal adherence was low, or vitronectin, where basal adherence was comparable with fibrinogen (Figure S9). These results suggested a role for signaling through the PAFR in αIIbβ3 activation in megakaryocytes. To further explore this possibility, we characterized activation of αIIb and β3 integrins in megakaryocytes that were left in suspension culture. Although cPAF had no effect on the relative surface expression of these integrin subunits (data not shown), cPAF induced a conformational change in αIIbβ3 integrins to an activated state as measured by binding of PAC-1 (Figures 4C and S10). Similarly, cPAF increased binding of soluble fibrinogen to megakaryocytes, and pretreatment with PAFR blocker inhibited this increase (Figure 4C). We also found that thrombin enhanced PAC-1 (Figure S10) and soluble fibrinogen binding (data not shown) to megakaryocytes, but unlike cPAF, thrombin-induced responses were not altered by pretreatment with the PAFR blocker (data not shown and Figure S6).

PAFR-dependent adherence and spreading in megakaryocytes relies on integrin αIIbβ3. (A) Megakaryocytes were placed on immobilized collagen or fibrinogen in the presence of 10 nM cPAF for 30 minutes. β-Tubulin was localized in the megakaryocytes (white stain). Scale bar represents 30 μm. (B) The number of megakaryocytes adherent to fibrinogen or collagen (ie, 30 minutes) in the presence of 10 nM cPAF. Panels A and B are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) PAC-1 and Alexa 488–conjugated fibrinogen (Fib-488) staining in megakaryocytes that were left in suspension culture. The megakaryocytes were treated with 10 nM cPAF in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker WEB 2086 (10 μM). The bars in panels B and C represent the mean ± SD. * identifies statistical significance (P < .05) between fibrinogen and collagen (B) or between cPAF and all the other treatments (C).

PAFR-dependent adherence and spreading in megakaryocytes relies on integrin αIIbβ3. (A) Megakaryocytes were placed on immobilized collagen or fibrinogen in the presence of 10 nM cPAF for 30 minutes. β-Tubulin was localized in the megakaryocytes (white stain). Scale bar represents 30 μm. (B) The number of megakaryocytes adherent to fibrinogen or collagen (ie, 30 minutes) in the presence of 10 nM cPAF. Panels A and B are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) PAC-1 and Alexa 488–conjugated fibrinogen (Fib-488) staining in megakaryocytes that were left in suspension culture. The megakaryocytes were treated with 10 nM cPAF in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker WEB 2086 (10 μM). The bars in panels B and C represent the mean ± SD. * identifies statistical significance (P < .05) between fibrinogen and collagen (B) or between cPAF and all the other treatments (C).

Discussion

PAF-AH is produced by human macrophages43 and transplantation studies from Asano and colleagues21 show that a large portion of circulating PAF-AH is derived from human bone marrow cells. The types of bone marrow cells that contribute to the PAF-AH pool, however, have not been well characterized. Here, we demonstrate that as human CD34+ cells differentiate into megakaryocytes they accumulate PAF-AH activity, which is primarily intracellular. Unlike differentiated megakaryocytes, we did not detect PAF-AH activity or PAF-like lipids in megakaryocyte precursors. Nevertheless, megakaryocyte precursors express mRNA for PAFR-1 and respond to PAFR-dependent signals whether they express integrin αIIbβ3 or not (data not shown).

We found that accumulation of PAF-AH in megakaryocytes prevents the buildup of bioactive PAF-like lipids, but not authentic PAF, that activate the PAFR. Temporal accumulation of PAF-AH also occurs in monocytes as they differentiate into macrophages,43 suggesting that signals delivered via the PAFR contribute to cellular differentiation. It is also likely that megakaryocytes produce PAF-AH to incorporate the enzyme into platelets during thrombopoiesis. Indeed, mature circulating platelets possess PAF-AH activity,44,45 which may modulate low levels of PAF synthesis that occur in platelets, PAF-induced aggregation, and signaling of myeloid leukocytes.45,46

Several PAF-AH isoforms are thought to contribute to the hydrolysis of PAF or PAF-like lipids. These include plasma PAF-AH, PAF-AH2, as well as PAF-AH1b2 and PAF-AH1b3 isoforms.19 All of the isoforms were detected at the mRNA level in megakaryocytes (Table 1), and the plasma PAF-AH and the type 1b2 isoform were confirmed at the protein level (Figures 1C and S2). Although our experiments do not distinguish which PAF-AH isoform or isoforms are responsible for the enzymatic activity in megakaryocytes several observations indicate that plasma PAF-AH modulates PAF-like lipid bioactivity. First, our unpublished observations (J.M.F., 2005) and observations of others44 indicate that the abundant enzyme in platelets is the plasma PAF-AH isoform. Second, mRNA and protein for plasma PAF-AH are induced during megakaryocyte differentiation (Figure 1). Third, the specific activity of the plasma PAF-AH isoform is 100-fold higher than either of the type 1 enzymes.47 Finally, Pefabloc quenches PAF-AH activity allowing PAF-like lipids to accumulate, and previous studies have demonstrated that Pefabloc inhibits the plasma PAF-AH40 but not the type 1 enzymes.47

Inhibition of endogenous PAF-AH activity in megakaryocytes allowed PAF-like lipids, but not PAF, to accumulate in treated cells. Accumulation of PAF-like lipids in megakaryocytes contrasts neutrophils where inhibition of PAF-AH has been linked to the synthesis of PAF.47 Megakaryocyte-derived PAF-like lipids activate the PAFR on neutrophils and megakaryocytes themselves. This suggests that dysregulated accumulation of PAF-like lipids may induce both autocrine and paracrine signaling events in the bone marrow milieu in hematopoietic cells that express a functional PAFR signaling system. It is not known, however, if megakaryocytes or other bone marrow–derived cells relay these types of signals through extracellular and/or intracellular PAFRs.

Accumulation of PAF-AH activity may provide a mechanism to modulate and control signals delivered through the PAFR in human bone marrow. We found that megakaryocytes adhere and spread more readily on immobilized fibrinogen after they are stimulated with cPAF, a stable analog of PAF, or when endogenous PAF-AH activity was quenched. Both of these conditions are associated with increased activation of αIIbβ3 integrins and binding of soluble fibrinogen. Increased binding of soluble fibrinogen occurs in stimulated megakaryocytes and is linked to αIIbβ3 signaling events.48,49 The mechanisms that lead to αIIbβ3 activation in megakaryocytes are incompletely understood, but platelet agonists enhance αIIbβ3-dependent responses in megakaryocytes.48,50 In this regard, we found that thrombin enhanced megakaryocyte adherence and spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. However, unlike cPAF treatment, binding and spreading of megakaryocytes in response to thrombin was not inhibited by a PAFR blocker (Figure S6). This suggests that protease activated receptors (PARs) cleaved by thrombin (PAR-1 and PAR-4) and the PAFR use independent downstream pathways to activate αIIbβ3 in megakaryocytes.

Similar to its effect on cell adhesion, spreading, and αIIbβ3 activation, cPAF enhanced migration of megakaryocytes through a porous membrane in a PAFR-dependent manner. This indicates that stimulation of the PAFR may modulate the movement of megakaryocytes as they migrate from osteoblastic niches to vascular beds within the bone marrow to produce proplatelets. Chemoattractant properties of the PAFR signaling system have been described in other cell types where PAF enhances the mobility of granulocytes, monocytes, and neurons.4,51-54

It is clear that the production of PAF-like lipids is under tight control during megakaryopoiesis. We have shown that megakaryocytes are active producers of PAF-AH and that inhibition of PAF-AH activity results in increased formation of PAF-like lipids. Unregulated PAF-like lipid production in the bone marrow could influence trafficking, activation, and gene expression patterns in neighboring cells. This may occur in conditions of oxidant stress, which has been shown to inactivate PAF-AH.55 Aberrant signaling through the PAFR may also influence packaging of critical proteins and/or mRNA transcripts into platelets25-27 during thrombopoiesis because platelet formation is a regulated process where both proteins and mRNAs are transported by microtubule-associated processes along cellular extensions to buds that will become proplatelets. Future studies examining the role of PAF-like lipids and other signaling molecules in megakaryopoiesis and platelet biogenesis may yield insights into signaling events that alter megakaryocyte and platelet behavior.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Kuhlman, Donnie Benson, and Jessica Phibbs for excellent technical assistance and the labor and delivery nurses and staff of Cottonwood and University of Utah hospitals for collecting umbilical cord blood for isolation of CD34+ hematopoietic cells. We also thank Chris Rodesch and the University of Utah School of Medicine Research Microscopy Facilities for technical assistance. Diana Lim was essential in preparation of the figures. We thank our colleagues in the Program in Human Molecular Biology and Genetics for helpful comments and critical review of the studies.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD; HL-44513 and HL081011 [T.M.M.], HL-66277 [A.S.W.], HL35828 [D.M.S.], and HL-44525 [G.A.Z.]).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.M.F. performed experiments and wrote the paper; G.K.M. and N.M. performed experiments; D.M.S. performed experiments and edited the paper; G.A.Z. and T.M.M. codirected experiments and edited the paper; and A.S.W. codirected experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andrew S. Weyrich, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah, 15 North 2030 East, Bldg 533, Rm 4220, Salt Lake City, UT 84112; e-mail: andy.weyrich@hmbg.utah.edu.

) to Fura-2 AM–loaded human PMNs to measure intracellular calcium release by fluorometry. This figure is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were loaded with Fluo-4 AM in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker, WEB 2086 (10 μM). The cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or 100 μM Pefabloc (PAF-AH inhibitor) to quench endogenous PAF-AH activity, and intracellular calcium fluxes were measured and are presented as mean peak fluorescence. The bars in panels A and C represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * in panels A and C indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with untreated or other treatment groups.

) to Fura-2 AM–loaded human PMNs to measure intracellular calcium release by fluorometry. This figure is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Megakaryocytes adherent to immobilized fibrinogen were loaded with Fluo-4 AM in the presence or absence of the PAFR blocker, WEB 2086 (10 μM). The cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or 100 μM Pefabloc (PAF-AH inhibitor) to quench endogenous PAF-AH activity, and intracellular calcium fluxes were measured and are presented as mean peak fluorescence. The bars in panels A and C represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. * in panels A and C indicates statistical significance (P < .05) compared with untreated or other treatment groups.