In this issue of Blood, Houot and colleagues report that T cells infiltrating human lymphomas express CD137, and that an agonistic CD137 antibody stimulates immune responses that exhibit potent activity against lymphomas transplanted into mice.1

The goal of recruiting the armory of the adaptive immune system, particularly T cells, against cancer has long attracted investigators. Since initial case reports that concurrent infections could result in responses or even cures of cancer, and exhortations to “stimulate the phagocytes” more than 100 years ago,2 researchers have sought methods to redirect cytotoxic responses against cells infected with pathogens instead of against cells transformed by somatic mutations. Unfortunately, thus far these hopes have not materialized into major impacts on cancer outcome. Nevertheless, immune-mediated treatments are firmly established within mainstream clinical practice, such as graft-versus leukemia/lymphoma effects, and monoclonal antibodies directed against tumor antigens—for example, rituximab—work, in part, through effects on T cells.

Although far from complete, our understanding of T-cell subsets continues to advance rapidly. Not only have various effector subsets, such as Th17, come to the fore, but several suppressive T cells, known as regulatory T (Treg) cells, are now characterized. Such cells act as negative feedback regulators of effector immune responses, to limit collateral tissue damage and mediate active immune tolerance. Which differentiation pathway each T cell takes is influenced by components of the innate immune system, which detect “pathogen-associated molecular patterns” for clues as to which type of immune response is required. These signals are finally transmitted from antigen-presenting cells to T cells by processes collectively known as costimulation. Without costimulation, T cells recognizing antigens presented on the MHC of antigen-presenting cells become either regulatory or anergic. Malignant cells appear to be active stimulators of regulatory T cells, and lymphoma cells are particularly active in this regard.3 It is likely that lack of costimulation is important in determining this balance.

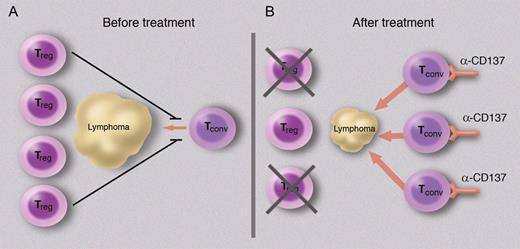

Translational researchers have been quick to incorporate these recent advances into experimental protocols, so different methods of artificial costimulation are being tried alongside methods of inhibiting regulatory T-cell responses. These complementary strategies are exemplified by the data reported by Houot et al.1 CD137 is an important costimulatory ligand and a potent stimulator of T-cell responses. It has been used therapeutically to stimulate immunity against several solid malignancies, culminating in several phase 1 trials, as well as modulate susceptibility to autoimmune disease and infection.4 In this issue, Houot et al first confirmed that it is one of the receptors expressed by lymphoma-infiltrating T cells. It is unclear whether its ligand is expressed on antigen-presenting cells from the tumor. Their next step was to validate the effects of an agonistic antibody against CD137 to enhance the immune response against a transplanted lymphoma in a murine model. They obtained convincing evidence that this antilymphoma treatment was effective and depletion of host Treg cells augmented this immune response (see figure).

Costimulation can change the balance between regulatory and effector T-cell responses to lymphoma. A schematic is shown to illustrate this balance; it does not attempt to incorporate important features such as the role of antigen-presenting cells. (A) At presentation, although some effector T cells infiltrate the tumor, they are not activated and the immune response is dominated by Treg cells and thus tolerance. (B) After administration of a costimulatory stimulus, here an agnostic monoclonal antibody directed against CD137, the conventional (effector) T cells become activated and exert cytotoxic effects on the lymphoma. Depletion of Treg cells accentuates the cytotoxicity. Professional illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Costimulation can change the balance between regulatory and effector T-cell responses to lymphoma. A schematic is shown to illustrate this balance; it does not attempt to incorporate important features such as the role of antigen-presenting cells. (A) At presentation, although some effector T cells infiltrate the tumor, they are not activated and the immune response is dominated by Treg cells and thus tolerance. (B) After administration of a costimulatory stimulus, here an agnostic monoclonal antibody directed against CD137, the conventional (effector) T cells become activated and exert cytotoxic effects on the lymphoma. Depletion of Treg cells accentuates the cytotoxicity. Professional illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

However, a number of caveats to these promising data should be borne in mind. CD137 is expressed on a wide variety of cells and anti-CD137 antibodies may have activities other than as simple agonists.5 The role of CD137 in Treg-cell function is uncertain6 and it paradoxically ameliorates certain autoimmune diseases.7,8 More broadly, the immune systems of mice are significantly different from those of humans and several other approaches that have yielded promising data in mice have proved ineffective in humans. The choice of which costimulatory pathways will be most effective to recruit therapeutically is not presently clear. Perhaps, as formulated by the prescient Sir Ralph Bloomfield Bonington,2 “But so long as you stimulate the phagocytes, what does it matter which particular sort of serum you use for the purpose?” Overall, it seems likely that the adaptive system will be increasingly recruited into our therapeutic armamentarium and that studies such as this one by Houot et al are a welcome step in this direction.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■