Platelets play a critical role in hemostasis and thrombosis. In this issue of Blood, a new study presented by Salles and colleagues demonstrates that functional human platelets can be generated in mice after transplantation of human hematopoietic stem cell progenitors.1 This method opens up new avenues to study thrombopoiesis and platelet function in vivo, and the effect of distinct genetic modifications.

Platelets are anucleated cells that play a central role in hemostasis and thrombosis. In the past, considerable interest has focused on the identification and characterization of pivotal platelet proteins to further evaluate platelet physiology and new pharmacologic strategies. That these proteins cannot be easily accessed hampers the study of the role of proteins in platelet function. Genetic modification of mature platelets is not possible, thus evaluation of the function of transgenes in platelets requires the generation of platelets from nucleated progenitor cells in vitro.

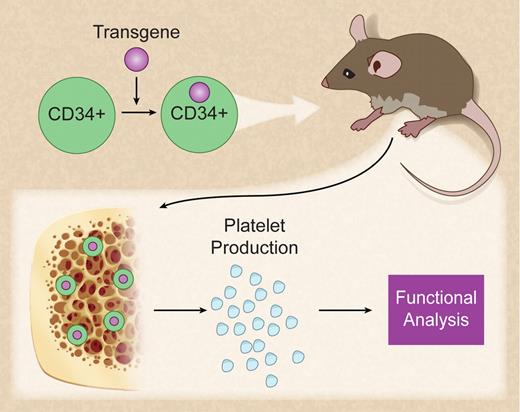

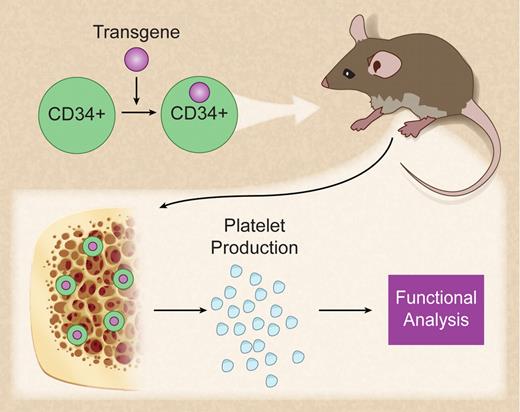

In vivo production of genetically modified human platelets. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

In vivo production of genetically modified human platelets. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

Several studies have shown that platelets can be generated from CD34-positive progenitor cells or from megakaryocytes in vitro, and that these culture-derived (CD) platelets have some characteristic morphologic features of mature platelets.2,3 The development of CD platelets permits expression of any protein of interest in these platelets and analysis of its function in the natural environment of primary mature platelets.4,5 However, this method previously has been limited to in vitro analysis.

The current article by Salles et al1 describes a mouse model that allows the study of the function of human platelets in vivo (see figure). The authors convincingly demonstrate for the first time that human platelets can be produced in NOD/SCID-mice after xenotransplantation of CD34-positive cord blood cells. Generation of human platelets occurred rapidly approximately 10 days after transplantation with a second peak at 5 weeks. Salles et al further show that human platelets generated in mice are functional as assessed by flow cytometry and thrombus formation in flow chamber experiments.

In summary, this intriguing new method opens an avenue for the exploration of the function of any protein in the environment of mature platelets in vivo. Defining the functional role of transgenes in platelets may disclose so far hidden targets to control platelet function and to evaluate new mechanisms in megakaryopoiesis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■