Abstract

Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) is a major mitotic regulator overexpressed in many solid tumors. Its role in hematopoietic malignancies is still poorly characterized. In this study, we demonstrate that Plk1 is highly expressed in leukemic cell lines, and overexpressed in a majority of samples from patients with acute myeloid leukemia compared with normal progenitors. A pharmacologic inhibitor, BI2536, blocks proliferation in established cell lines, and dramatically inhibits the clonogenic potential of leukemic cells from patients. Plk1 knockdown by small interfering RNA also blocked proliferation of leukemic cell lines and the clonogenic potential of primary cells from patients. Interestingly, normal primary hematopoietic progenitors are less sensitive to Plk1 inhibition than leukemic cells, whose proliferation is dramatically decreased by the inhibitor. These results highlight Plk1 as a potentially interesting therapeutic target for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia.

Introduction

Polo-like kinase (Plk) 1 is a key actor of the cell cycle at the G2/M transition and in mitosis.1 Among its substrates are the mitotic regulators cyclin B, CDC25C phosphatase, and Wee1 kinase. Four identified Plks have distinct and sometimes opposite functions. Plk1 is involved in mitosis, whereas Plk2 and Plk3 regulate the G1 and early S phases.2 Plk1 is overexpressed in many cancers,3 including melanoma, lymphoma, and several carcinomas, although Plk3 is down-regulated in various neoplasic tissues,4 but can also induce S phase entry.3 Epigenetic inactivation of Plk25 occurs in hematologic malignancies, suggesting a tumor suppressor function

Plk1 has been extensively studied as a potential therapeutic target these last years.6 Pharmacologic inhibitors like ON019107 and BI25368 affect proliferation and induce apoptosis in cancer cells, leading to tumor regression in xenograft models. Although it has been shown overexpressed in lymphomas,9 the status of Plk1 in hematologic malignancies is still poorly characterized.

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by concomitant differentiation arrest and deregulated proliferation and resistance of stem and/or progenitor cells,10 linked to mutations affecting transcription factors and signal transduction players. The cell-cycle regulator cyclin A1 is frequently overexpressed or abnormally localized in leukemic cells,11,12 and its transgenic overexpression induces acute leukemia in mice.13 The Aurora A kinase, sharing functional mitotic properties with Plk1, is also overexpressed in leukemia. Its inhibition causes growth arrest and apoptosis14 and sensitizes AML cells to chemotherapeutic agents.15

In this study, we show that Plk1 is overexpressed in AML cell lines and in a large percentage of samples from patients, and that its inhibition or knockdown preferentially blocks proliferation of leukemic rather than normal cells.

Methods

AML cells were obtained from patients at the Department of Hematology (Toulouse University Medical Center) after informed consent was provided in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and were isolated and cryopreserved, as described.16 Normal cord blood CD34+ cells were from Stem Cells Biotechnologies. The human cell lines KG1, KG1a, U937, HEL, HL60, UT7-Epo, and HCT116 (ATCC) were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS; KG1, KG1a), RPMI/10% FCS (U937, HEL, HL60), Dulbecco modified Eagle medium/10% FCS, and 1 UI/L erythropoietin (UT7-Epo1), or in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium/10% FCS (HCT116) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and the Plk1 inhibitor BI2536, synthesized as described (patent wo 2004/076454 AI; Boehringer Ingelheim), were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide and stored at −20°C. Samples were obtained from Collection d'hémopathies malignes de l'Inserm Midi-Pyrénées. Collection d'hémopathies malignes de l'Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale Midi-Pyrénées was declared to the government (DC-2008-307) and obtained a transfer agrement (AC-2008-129). Informed consent was approved by Comité de Protection des Personnes of Sud-Ouest et Outre-mer II.

Proteins from 5 × 105 cells denatured in Laemmli buffer were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto nitrocellulose (Amersham Biosciences), and probed with the appropriate antibodies (anti-Plk1 antibody [Invitrogen], anti-actin [Sigma-Aldrich], anti-Wee1 [Santa Cruz Biotechnology], and secondary antibodies [Cell Signaling Technology]), as described.17

KG1 (Kit R, program V-01), U937 (kit V, program V-01), and primary AML (kit V, program U-15) cells were transfected with Plk1 or control small interfering RNA (siRNA; Dharmacon) by nucleofection (Amaxa), according to the manufacturer. Cells were then cultured from 24 to 72 hours for further analysis or immediately processed for clonogenic assays. For this, cells (105 cells/mL) were grown in H4230 methyl cellulose medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 10% 5637-conditioned medium, as described.16-18 Normal bone marrow CD34+ hematopoietic cells were tested for clonogenicity, as described.16 Normal and leukemic primary cells were grown in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium containing 10% FCS, stem cell factor (100 ng/mL), interleukin-3 (5 ng/mL), FLT3 ligand (100 ng/mL), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (10 ng/mL).17

KG1 and U937 cells (2 × 105) were grown in 96 wells for 4 days and counted each day by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide assay (Sigma-Aldrich). For apoptosis detection, cells were labeled with propidium iodide and annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (BD Pharmingen) and analyzed by flow cytometry (EPICS XL-MCL; Beckman Coulter). For cell-cycle analysis, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline with 5.5 mM glucose, fixed in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 50 μg/mL propidium iodide, and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. DNA content was monitored by flow cytometry (EPICS XL-MCL; Beckman Coulter).

Results and discussion

Plk-1 is overexpressed in AML cells

Western blot analysis shows that all AML cell lines expressed significant levels of Plk1, except HL-60 (Figure 1A left panel). High levels of Plk1 were also detected in a majority (14 of 22) of blasts from patients, whereas it was hardly detectable in normal human CD34+ and peripheral blood leukocyte cells (Figure 1A right panel). No correlation was found between Plk1 levels and French-American-British or cytogenetic parameters (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). In some samples, abnormally migrating forms of PLK1 were observed (see patient no. 5). A majority of these isolated leukemic blasts were nonproliferating and mainly blocked in G0/G1 (data not shown), consistent with the fact that usually less than 2% of these cells have clonogenic potential. Normal CD34+ were also nonproliferating under our conditions (data not shown). Thus, elevated Plk1 levels are not reflecting high proliferation rates in these experiments. These data are in agreement with recent studies performed in U937 cells,19 and suggesting up-regulation of Plk-1 in AML samples.20 Plk1 is overexpressed in large B-cell lymphoma, where it was proposed as an independent prognostic factor.21 Whether this is the case in AML will need further investigations on a larger cohort of patients. The mechanisms of Plk1 up-regulation in cancer cells remain unclear. Transcriptional factors regulating Plk1 include BRCA1, the pRb family members, or the Forkhead factor FoxM1.22-24 Chfr-dependent proteasomal degradation of Plk1 was also described,25 as well as its stabilizing interaction with the heat shock protein 90.26 Analysis of the relative implication of these different pathways in AML will represent a challenge in the future.

Analysis of Plk1 expression and inhibition in AML cell lines. (A) Exponentially growing AML cell lines (left panel) and primary samples from patients with AML (patients 1-22) or from healthy donor (CD34+ and peripheral blood leukocytes [PBL]; right panel) were processed for Western blot analysis of Plk1. Samples 1, 10, and 12 were used as standards to allow comparison of Plk1 levels between the 4 membranes. The membranes were stripped and reprobed for actin detection as a loading control. Data in the left panel are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) KG1 and U937 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 3 days. C indicates control curve. Cell viability was quantified by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide. Results are mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. (C) Top left: KG1 cells were grown in clonogenic assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of BI2536 (control, ■; 1 nM,  ; 10 nM, ▧). Colonies were scored at day 7 after seeding. Results are presented as percentage of CFU-L for each BI2536 concentration relative to untreated cells and are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (Bottom left) To check the efficiency of Plk1 inhibition, KG1 cells were treated for 4 hours with increasing concentrations (1 nM and 10 nM) of BI2536. The corresponding fractions were then analyzed by Western blot with an antibody against the Wee1 kinase, whose stability is reduced via phosphorylation by Plk1. Western blot against actin was used as a loading control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Top right) KG1 cells were cultured for 3 days after electroporation with Plk1 or control siRNA. Every day, the number of viable cells was assessed by trypan blue staining. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Bottom right) Western blot analysis of Plk1 in KG1 cells transfected with control (C) or Plk1 siRNA. (D) KG1 and U937 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 48 hours, and analyzed for apoptosis induction by annexin V staining. Results are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

; 10 nM, ▧). Colonies were scored at day 7 after seeding. Results are presented as percentage of CFU-L for each BI2536 concentration relative to untreated cells and are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (Bottom left) To check the efficiency of Plk1 inhibition, KG1 cells were treated for 4 hours with increasing concentrations (1 nM and 10 nM) of BI2536. The corresponding fractions were then analyzed by Western blot with an antibody against the Wee1 kinase, whose stability is reduced via phosphorylation by Plk1. Western blot against actin was used as a loading control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Top right) KG1 cells were cultured for 3 days after electroporation with Plk1 or control siRNA. Every day, the number of viable cells was assessed by trypan blue staining. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Bottom right) Western blot analysis of Plk1 in KG1 cells transfected with control (C) or Plk1 siRNA. (D) KG1 and U937 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 48 hours, and analyzed for apoptosis induction by annexin V staining. Results are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Analysis of Plk1 expression and inhibition in AML cell lines. (A) Exponentially growing AML cell lines (left panel) and primary samples from patients with AML (patients 1-22) or from healthy donor (CD34+ and peripheral blood leukocytes [PBL]; right panel) were processed for Western blot analysis of Plk1. Samples 1, 10, and 12 were used as standards to allow comparison of Plk1 levels between the 4 membranes. The membranes were stripped and reprobed for actin detection as a loading control. Data in the left panel are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) KG1 and U937 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 3 days. C indicates control curve. Cell viability was quantified by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide. Results are mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. (C) Top left: KG1 cells were grown in clonogenic assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of BI2536 (control, ■; 1 nM,  ; 10 nM, ▧). Colonies were scored at day 7 after seeding. Results are presented as percentage of CFU-L for each BI2536 concentration relative to untreated cells and are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (Bottom left) To check the efficiency of Plk1 inhibition, KG1 cells were treated for 4 hours with increasing concentrations (1 nM and 10 nM) of BI2536. The corresponding fractions were then analyzed by Western blot with an antibody against the Wee1 kinase, whose stability is reduced via phosphorylation by Plk1. Western blot against actin was used as a loading control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Top right) KG1 cells were cultured for 3 days after electroporation with Plk1 or control siRNA. Every day, the number of viable cells was assessed by trypan blue staining. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Bottom right) Western blot analysis of Plk1 in KG1 cells transfected with control (C) or Plk1 siRNA. (D) KG1 and U937 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 48 hours, and analyzed for apoptosis induction by annexin V staining. Results are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

; 10 nM, ▧). Colonies were scored at day 7 after seeding. Results are presented as percentage of CFU-L for each BI2536 concentration relative to untreated cells and are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (Bottom left) To check the efficiency of Plk1 inhibition, KG1 cells were treated for 4 hours with increasing concentrations (1 nM and 10 nM) of BI2536. The corresponding fractions were then analyzed by Western blot with an antibody against the Wee1 kinase, whose stability is reduced via phosphorylation by Plk1. Western blot against actin was used as a loading control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Top right) KG1 cells were cultured for 3 days after electroporation with Plk1 or control siRNA. Every day, the number of viable cells was assessed by trypan blue staining. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Bottom right) Western blot analysis of Plk1 in KG1 cells transfected with control (C) or Plk1 siRNA. (D) KG1 and U937 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 48 hours, and analyzed for apoptosis induction by annexin V staining. Results are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Effects of Plk1 inhibition on leukemic cell lines

We used the pharmacologic inhibitor BI2536,8 known to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in various cancer cells, to evaluate the importance of Plk1 in U937 and KG1 cell proliferation (Figure 1B). A dramatic inhibition occurred with 10 nM BI2356 in both cell lines, KG1 cells being slightly more resistant than U937. The HL-60 cells, which contain low levels of PLK1, were highly insensitive to 10 nM BI2536 (data not shown). The clonogenic potential of KG1 cells was reduced by 50% with 1 nM BI2536, and strongly blocked with 10 nM (Figure 1C left top panel). The level of Wee1, a Plk1 substrate degraded by the proteasome after its phosphorylation, increased upon treatment with BI2356 (left bottom panel). Moreover, siRNA-mediated down-regulation of Plk1 efficiently inhibited KG1 cell proliferation (Figure 1C right panel). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of KG1 cells treated with PLK1 siRNA shows significant G2/M cell-cycle arrest (Supplemental Figure 2). Similar results were observed upon treatment with BI2536. The effect of BI2536 on cell death in leukemic cell lines was then investigated. Upon treatment of U937 and KG1 cells with this inhibitor for 48 hours, apoptosis was essentially detected at 100 nM in both cell lines, probably reflecting off-target effects of this drug at this concentration (Figure 1D).

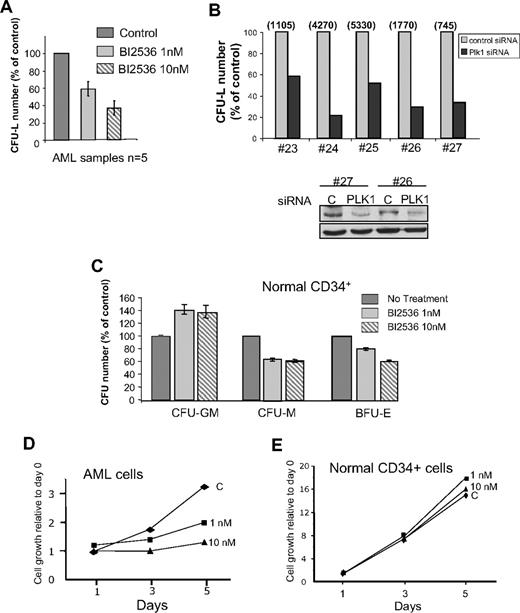

Effects of Plk1 inhibition on primary hematopoietic progenitors and leukemic cells

A total of 1 nM and 10 nM BI2536 reduced by 40% and 65% the clonogenic potential of leukemic cells from patients, respectively (Figure 2A). Plk1 siRNA-treated primary AML cells dramatically reduced their clonogenic potential (Figure 2B), confirming the central role of Plk1 for this function. In the samples tested, siRNA significantly decreased the protein level after 24 hours (Figure 2B bottom panel). By comparison, BI2536 did not inhibit the capacity of normal CD34+ cells to form colony-forming unit (CFU)–granulomonocyte, whereas CFU-monocyte and burst-forming unit–erythrocyte were moderately affected (Figure 2C). This modest effect preferentially affecting specific lineages suggests different degrees of implication of Plk1 in the proliferation of each lineage. Overall, these data indicate that the clonogenic potential of normal CD34+ cells is less affected by Plk1 inhibition than that of leukemic cells. We then tested the proliferation of normal CD34+ progenitors and of primary AML cells in liquid culture, in the presence of stem cell factor, interleukin-3, FLT3 ligand, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Figure 2D-E). Whereas leukemic cells stopped to proliferate with 10 nM BI2536, normal cells were not affected by this concentration of the inhibitor. At 100 nM, the proliferation of both cell types was impaired (data not shown).

Effects of Plk1 inhibition on normal hematopoietic CD34+ progenitors and AML primary cells from patients. (A) Fresh AML cells were grown in clonogenic assays in the presence of increasing doses of BI2536. Results are presented as percentage of control and are mean ± SD of duplicates from 5 patients tested. (B) AML cells from patients were transfected with Plk1-specific or control siRNA, and grown in clonogenic assays as in panel A (top panel). Representative data showing the efficiency of PLK1 knockdown by Western blot are shown (bottom panel). Results are presented as percentage of control for each patient, and the absolute number of colonies for each control condition was indicated on the top of the figure. (C) Normal CD34+ progenitors were grown for 14 days in similar conditions as in (A), in the medium indicated in “Methods.” Results shown are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (D) Primary AML cells were grown in liquid cultures in the conditions described in “Methods,” and counted each day in the presence of trypan blue. The proliferation rate was compared in the presence of 1 nM and 10 nM, or in the absence of B12536. This experiment is representative of results obtained with 4 patients. (E) Same experiment as in panel C, but performed with primary normal CD34+ cells from healthy donors. This graph is representative of 2 experiments performed in duplicate.

Effects of Plk1 inhibition on normal hematopoietic CD34+ progenitors and AML primary cells from patients. (A) Fresh AML cells were grown in clonogenic assays in the presence of increasing doses of BI2536. Results are presented as percentage of control and are mean ± SD of duplicates from 5 patients tested. (B) AML cells from patients were transfected with Plk1-specific or control siRNA, and grown in clonogenic assays as in panel A (top panel). Representative data showing the efficiency of PLK1 knockdown by Western blot are shown (bottom panel). Results are presented as percentage of control for each patient, and the absolute number of colonies for each control condition was indicated on the top of the figure. (C) Normal CD34+ progenitors were grown for 14 days in similar conditions as in (A), in the medium indicated in “Methods.” Results shown are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (D) Primary AML cells were grown in liquid cultures in the conditions described in “Methods,” and counted each day in the presence of trypan blue. The proliferation rate was compared in the presence of 1 nM and 10 nM, or in the absence of B12536. This experiment is representative of results obtained with 4 patients. (E) Same experiment as in panel C, but performed with primary normal CD34+ cells from healthy donors. This graph is representative of 2 experiments performed in duplicate.

In addition, we measured BI2536-induced apoptosis in primary proliferating CD34+ normal progenitors. These cells are largely insensitive to 10 nM inhibitor, whereas 100 nM induced massive apoptosis (Supplemental Figure 1). Altogether these data confirm that inhibiting Plk1 with 10 nM BI2536 blocks the proliferation of AML cells, while sparing the behavior of their normal hematopoietic counterparts. Higher concentrations (100 nM) induce apoptosis in all cell types tested, suggesting off-target effects. In consequence, low concentrations of this inhibitor should be considered for further pharmacologic evaluation of the targets in vivo.

In conclusion, Plk1 is often overexpressed in AML, where it plays a critical function during proliferation. Plk1 inhibition has modest effects in normal hematopoietic cells, suggesting that overexpression of the protein in leukemic cells may account for higher sensitivity to the inhibitor. Thus, leukemic cells most likely became highly dependent of Plk1 for their proliferation compared with their normal counterparts, opening potentially important pharmacologic perspectives for the treatment of AML with Plk1 inhibitors, either alone or in combination with other drugs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Cecile Demur for helpful discussion about the manuscript and to Nathalie Gallay for helpful managing of patients' samples.

This work was supported by the Région Midi-Pyrénées and the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer.

Authorship

Contribution: A.G.R. and C.D.S. performed research and analyzed data; C.R. contributed AML samples and analyzed data; C.B. analyzed data; L.C. and A.K. designed research and analyzed data; B.P. designed research and wrote the paper; and S.M. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stéphane Manenti, Inserm Unité 563, CPTP, Batiment B, CHU Purpan, 31024, Toulouse Cedex 3, France; e-mail: stephane.manenti@toulouse.inserm.fr.

![Figure 1. Analysis of Plk1 expression and inhibition in AML cell lines. (A) Exponentially growing AML cell lines (left panel) and primary samples from patients with AML (patients 1-22) or from healthy donor (CD34+ and peripheral blood leukocytes [PBL]; right panel) were processed for Western blot analysis of Plk1. Samples 1, 10, and 12 were used as standards to allow comparison of Plk1 levels between the 4 membranes. The membranes were stripped and reprobed for actin detection as a loading control. Data in the left panel are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) KG1 and U937 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 3 days. C indicates control curve. Cell viability was quantified by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide. Results are mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. (C) Top left: KG1 cells were grown in clonogenic assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of BI2536 (control, ■; 1 nM, ; 10 nM, ▧). Colonies were scored at day 7 after seeding. Results are presented as percentage of CFU-L for each BI2536 concentration relative to untreated cells and are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (Bottom left) To check the efficiency of Plk1 inhibition, KG1 cells were treated for 4 hours with increasing concentrations (1 nM and 10 nM) of BI2536. The corresponding fractions were then analyzed by Western blot with an antibody against the Wee1 kinase, whose stability is reduced via phosphorylation by Plk1. Western blot against actin was used as a loading control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Top right) KG1 cells were cultured for 3 days after electroporation with Plk1 or control siRNA. Every day, the number of viable cells was assessed by trypan blue staining. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (Bottom right) Western blot analysis of Plk1 in KG1 cells transfected with control (C) or Plk1 siRNA. (D) KG1 and U937 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BI2536 (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) for 48 hours, and analyzed for apoptosis induction by annexin V staining. Results are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/3/10.1182_blood-2008-12-195867/4/m_zh89990939270001.jpeg?Expires=1768072434&Signature=hoaHvOjnd9j-cbCuRtkbbm25G2rrbQHMPzGKrXUalVJ4VmBIaDds-FNx2vbziFRn4z8hQJsIziZL-k8V-Tx5T6ICqKfJBQUAt0HODaMwmxZ2f2Di0wYswKAJElvaEy8b-S1Yv01qs3JqEYIGFXf5hps5EVk0dCazJFnVU9Oczlf8PP1SADUypNiavavq73-r10g-Q8Szjx3C3m7T~TXhIOYrG1JcDW10B7fAJ7NfuOW3itRVcToe0n5drMlYbogAgylCeTpFuzrO-V2zXpYl~kzXhHLzsEZndPgZ~k5r7VculD2VOqGxJctAPiSRfVOKhl2o2qYgdc5KjmmhrSYH9w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)