Abstract

We previously reported that patients with fibrotic, chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) have antibodies activating the platelet-derived growth factor receptor pathway. Because this pathway can be inhibited by imatinib, we performed a pilot study including 19 patients with refractory cGVHD, given imatinib at a starting dose of 100 mg per day. All patients had active cGVHD with measurable involvement of skin or other districts and had previously failed at least 2 treatment lines. Patient median age was 29 years (range, 10-62 years), and median duration of cGvHD was 37 months (range, 4-107 months). The organs involved were skin (n = 17), lung (n = 11), and bowel (n = 5); 15 patients had sicca syndrome. Imatinib-related, grade 3 to 4 toxicity included fluid retention, infections, and anemia. Imatinib was discontinued in 8 patients: in 3 because of toxicity and in 5 because of lack of response (n = 3) or relapse of malignancy (n = 2). Overall response rate at 6 months was 79%, with 7 complete remissions (CRs) and 8 partial remissions (PRs). With a median follow-up of 17 months, 16 patients are alive, 14 still in CR or PR. The 18-month probability of overall survival is 84%. This study suggests that imatinib is a promising treatment for patients with refractory fibrotic cGVHD.

Introduction

Over the past decade, significant changes have been made in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, including wider use of this procedure in older patients, more transplantations from unrelated and HLA-disparate related donors, and widespread use of peripheral blood as stem cell source. All these factors have contributed to increase the prevalence of chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD).1

The exact pathogenesis of cGVHD is still incompletely defined,2 and the role of alloreactivity versus autoreactivity remains an area of debate. Alloreactivity of donor lymphocytes toward unshared recipient minor histocompatibility antigens is advocated to interpret cGVHD as a late phase of acute GVHD; the importance of autoreactivity, however, is suggested by clinical manifestations of cGVHD that mimic those of autoimmune diseases. In particular, the typical sicca syndrome in patients with cGVHD resembles that of patients with Sjögren syndrome, enteropathy can mimic Crohn disease, and skin manifestations recall systemic sclerosis (SSc).3

Treatment of cGVHD is based on immune-suppressive agents, usually steroids, associated with a calcineurin inhibitor,4,5 but other therapies have been tested, including mofetil mycophenolate, extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab [RTX]).6-9 Response is often unsatisfactory, and prolonged treatment with these agents contributes to the state of profound immune deficiency that characterizes patients with cGVHD and is responsible for the increased risk of developing severe, sometimes even life-threatening or fatal, infectious complications. Indeed, cGVHD has been identified as the leading cause of late nonrelapse mortality in survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.10

We have recently shown that patients with cGVHD showing fibrotic/sclerotic manifestations have agonistic antibodies activating the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF) receptor.11 The presence and biologic activity of these autoantibodies argue for a common pathogenic trait in both cGVDH and SSc,11,12 in that up-regulation of the PDGF receptor intracellular pathway leads to increased reactive oxygen species, with consequent exaggerated collagen synthesis, which, in turn, contributes to the pathologic lesions observed in both cGVHD and SSc.

Much data strongly suggest that, among the profibrotic cytokines, besides PDGF,13 also transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) can play a relevant role in the pathogenesis of SSc. Indeed, both PDGF and TGF-β pathways seem to be up-regulated in the skin of patients with SSc, and, in a murine model of cGVHD, anti–TGF-β antibodies prevented the development of skin fibrosis.14 Moreover, blockade of either TGF-β or PDGF signaling has been shown to reduce the development of fibrosis in various experimental models.15,16 Recent in vitro data showed that imatinib strongly inhibits both PDGF and TGF-β intracellular signaling, which is responsible for the expression of extracellular matrix genes.17 In this experimental model, the highest concentration of imatinib was 1.0 μg/mL, a value within the mean trough concentration observed after administration to patients of drug doses between 200 and 400 mg per day.

Currently, imatinib is widely used in patients with Philadelphia-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In view of the specific capacity of imatinib to inhibit both TGF-β and PDGF signaling pathways, the long-standing clinical experience with this drug, and its good tolerability in patients with CML and acute lymphoblastic leukemia,18 we speculated that imatinib could be a possible option for treating patients with cGVHD, refractory to conventional treatment, when sclerotic/fibrotic clinical features are present.

Methods

Patient characteristics

Nineteen patients, affected by refractory cGVHD with fibrotic/sclerotic clinical features, were enrolled in the study; median age was 29 years (range, 10-62 years). The main characteristics of these patients are detailed in Table 1. The major involved organs were skin (n = 17), lung (n = 11), and bowel (n = 5); sicca syndrome was diagnosed in 15 patients. On the whole, 11 had generalized cutaneous scleroderma features, and 13 patients had visceral involvement (excluding sicca syndrome). The diagnosis of sicca syndrome was based on the clinical criteria elaborated by the American-European Consensus Group, without including serologic markers, which, by contrast, are considered in patients with the classical Sjögren syndrome19 ; in all 15 patients with sicca syndrome a pathologic Schirmer test was present (see supplemental file for details, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Among the 11 patients with generalized skin fibrosis, 5 also had visceral involvement. In the 8 patients who did not show generalized skin sclerosis, 6 had localized skin fibrotic involvement associated with visceral involvement, 1 patient had only diffuse fasciitis (histologically proven), and the remaining patient had severe lung fibrosis in the absence of any skin involvement.

End points

The primary end point of this study was to assess the safety [in terms of incidence of severe adverse events (SAEs) and hematologic tolerance] of escalating doses of imatinib in patients with sclerotic/fibrotic refractory cGVHD. Secondary end points were response rate and overall survival (OS) at 3 and 6 months after beginning imatinib therapy. The study was designed as a phase 1 to 2 trial, initially planned to enroll 15 patients, and approved by the Ethic Committee of the Coordinating Center of Potenza (Eudract no. 2007-001508-19). Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec; 100-mg tablets; Novartis, Switzerland) was administered off label.

In all patients, written informed consent to treatment was obtained after having exhaustively discussed the potential benefits and risks of imatinib therapy, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent to collect, handle, and store personal data were also obtained from all enrolled patients. Incapacitated persons were not involved in the study; for patients younger than 18 years who were treated in the 2 pediatric centers, a written, informed consent from both parents was obtained. In view of the rapid accrual of the first 15 patients and the encouraging response rate, the institutional review board decided, for ethical reasons, to enroll 4 more patients, while waiting for the next phase 2 multicenter Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Midollo Osseo study to start. This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Coordinating Center of Potenza.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were eligible to be included in the study if they met the following criteria. (1) They had a diagnosis of extensive cGVHD with fibrotic scleroderma-like features (this definition included skin generalized fibrosis, lung fibrosis, gut fibrosis, or any other extensive fibrotic process affecting normal physiologic functions). The fibrotic process had to be documented histologically; in detail, in the patients with sclerotic cutaneous involvement (including fasciitis) a skin biopsy had been performed; also in 5 patients who showed gastrointestinal (GI) involvement (liver and gut), the diagnosis of cGVHD was documented histologically. Only in one patient with extensive and severe lung fibrosis (UPN 1346), the diagnosis of cGVHD was not supported by histology and was based both on classic clinical features, computed tomography scan of the chest and lung functional test evaluation. A measure of organ function alterations had also to be available, ie, percentage of body surface area (BSA), total skin thickness score (TSC), and Zubrod performance status for skin involvement; forced expiratory volume, forced vital capacity, and carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity, together with high-resolution chest compute tomography scan for lung involvement. (2) They had failed at least 2 lines of immunosuppressive therapy, including steroids, either as first- or second-line therapy (all 19 patients had received prednisone orally at dosages ranging from 0.5 to 1 mg/kg per day for at least 3 months after an induction phase of 7-10 days of prednisone at 2 mg/kg per day). (3) They had active disease with at least one of the following manifestations: generalized skin sclerosis, symptomatic bronchiolitis obliterans pneumonia (in the absence of intercurrent infectious complications), extensive lung fibrosis, pathologically demonstrated visceral fibrotic involvement of the gut.

Exclusion criteria were stable disease controlled by standard treatment (including a daily maintenance dose of prednisone < 0.4 mg/kg per day), RTX administration in the preceding 6 months, pregnancy, and secondary malignancy.

Treatment schedule

Imatinib administration was planned for a minimum of 6 months, starting at the initial dose of 100 mg per day. After 1 month, in absence of SAEs, toxicity, or intolerance, the dose could be increased to 200 mg per day until the end of the third month; afterward, if no response had occurred, in the absence of SAEs, toxicity, or intolerance, patients were allowed to receive 400 mg per day. Total treatment duration depended on the clinical situation of the patient and his or her response to therapy with imatinib. Concomitant immunosuppressive treatment was allowed, according to the clinician's decision, including steroid maintenance. The concomitant administration of other myelotoxic drugs was not permitted. If some patients had been previously included in a salvage program with ECP, the continuation of this treatment was allowed, whereas RTX administration was not. Supportive care/other medications were given, according to institutional guidelines or local practice or both. Patients were strictly monitored during imatinib treatment to evaluate the treatment safety and unexpected SAEs, according to the guidelines currently available.20

Response criteria

Response (evaluated at 3 and 6 months after beginning imatinib) was defined as complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), according to the criteria proposed by Couriel et al8 integrated by some chronic GVHD–specific core measures for organ-specific manifestations, as suggested by Pavletic et al.21 CR was defined as resolution of all manifestations of skin cGVHD (in terms of sclerosis, erythematous rash, or ulcers) and resolution of all manifestations related to chronic GVHD in the specific organs involved, except for some irreversible changes.

PR was established according to the response evaluated in the main involved organs as follows: for generalized skin involvement, PR was defined as at least 50% improvement of BSA involved (in terms of sclerosis, erythematous rash, or ulcers). A significant improvement in Zubrod performance status by 1 or more (confirming a functional improvement) was also required (Zubrod performance status was attributed by a senior physician expert in cGVHD management). To exactly measure response (both in terms of BSA involved and skin thickness) in patients with cutaneous sclerotic lesions, a TSC, calculated according to the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) system,22 was used. This score consists of an evaluation of the patient's skin thickness rated by clinical palpation with the use of a scale from 0 to 3 (0 = normal skin; 1 = mild thickening; 2 = moderate thickening; 3 = severe thickening with inability to pinch the skin into a fold) for each of 17 anatomic surface areas of the body: face, anterior chest, abdomen, (right and left separately) fingers, forearms, upper arms, thighs, lower legs, dorsum of hands, and feet. These individual values are added, and the sum is defined as the TSC. Because most patients had only sclerotic cutaneous involvement (except 2 who also had ulcers or erythematous rash), the skin response was measured in terms of reduction of the BSA involved and improvement of the mRSS. PR for ocular cGVHD was defined as subjective improvement, with at least 50% reduction in the frequency of artificial tear administration or as improvement in Schirmer test in one or both eyes of at least 3 mm. For the respiratory tract, PR was defined as sustained, measurable improvement in pulmonary function tests (carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity, forced expiratory volume, or both) or the ability to reduce corticosteroids by at least 50% or both without deterioration of pulmonary function. To better standardize the functional respiratory improvement a lung functional score was calculated before and after treatment, as suggested by the National Institute of Health Consensus Conference for cGVHD20 ; similarly in patients with GI involvement the responses were also graded according to severity scales from 0 to 3 (details for response evaluation in the main organs involved are reported in a supplemental file).

No response (NR) was defined as no change in cGVHD manifestations or any minor response (MR) not fulfilling the above-mentioned criteria for PR; patients who experienced early death as a result of cGVHD before the time chosen for the assessment of response, as well as those requiring an increase in steroid dosage, were considered as having had NR. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as any worsening of cGVHD clinical manifestations while on treatment; patients with CR or PR in one organ and simultaneous NR or PD in another were considered to have had a mixed response (MXR). NR, MR, PD, and mixed response were considered to be treatment failures (TFs).

Statistical considerations

With the use of the Simon minimax design23 15 patients have been planned to be recruited in the first initial design, based on the following stopping rules: more than one death potentially correlated to the treatment and less than 7 responses (considered as CR and PR). Data were analyzed with SPSS package (Version 13.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc) and NCSS 2007 (NCSS, PASS, and GESS, Kaysville, UT). OS was measured from the start of imatinib administration until death because of any reason and calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. The probability of imatinib TF was expressed as cumulative incidence (CI), to adjust the analysis for competing risks. CI was calculated from the start of imatinib treatment to the last follow-up, to whichever event was considered TF (either intolerance to the drug or lack of response), or to a competing event (relapse, development of second neoplasia, or death because of causes independent of cGVHD).24

Results

Toxicity

The main hematologic and extrahematologic toxicities are reported in Table 3. Four patients developed relevant extrahematologic side effects, in 3 cases requiring imatinib discontinuation. Of them, 1 patient (UPN 310AR) developed John Cunningham virus encephalitis, and 2 experienced important fluid retention: 1 patient (UPN 1602) developed pleural effusion and another (UPN 99992) developed diffuse subcutaneous edema, which both disappeared after drug discontinuation. In these 3 patients who stopped the treatment, the dosage of imatinib at the time of drug discontinuation was 100 mg per day. The fourth patient (UPN 1348, who had a previous history of several episodes of respiratory infection before imatinib) developed pneumonia, which successfully responded to antibiotic therapy, without interrupting treatment with imatinib. One more patient (UPN 1064) with CML developed anemia, requiring treatment with recombinant human erythropoietin.

With a median observation time of 17 months from start of imatinib (range, 8-22 months), 11 patients are still on imatinib treatment, and in 8 patients treatment was discontinued. Reasons for discontinuation were intolerance (the 3 patients reported earlier), lack of response (n = 3), and relapse of the original disorder (n = 2). The first relapsed patient (UPN 1467) was a woman with multiple myeloma (MM), who had an extramedullary relapse 6 months after inception of imatinib, requiring combined therapy with surgical intervention, followed by radiotherapy and donor lymphocyte infusions; up to now, the patient is alive and well, without signs of MM and stable improvement of cGVHD even after imatinib discontinuation. The second patient (UPN 1) was a woman with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), who achieved PR after 6 months of imatinib treatment, but developed extramedullary (skin) relapse after 8 months of therapy; she received salvage therapy without response and died of leukemia.

A second tumor occurred in a patient (UPN 1064) with CML, who developed an abdominal mass; a surgical biopsy showed pathologic findings of diffuse large cell lymphoma (DLCL). The dramatic unfavorable evolution of this secondary tumor did not allow any further treatment, and the patient died 1 month later. We cannot exclude a relation between the imatinib treatment and the development of a secondary neoplasia.

Finally, we observed a further fatality in a patient (UPN 99992), who died because of interstitial pneumonia, possibly attributable to the profound immune depression, 207 days after imatinib discontinuation; in this case treatment had been stopped because of toxicity (diffuse subcutaneous edema), and the patient was unresponsive.

Response

After 3 months of treatment, we observed, among the 19 evaluable patients, 1 CR (5%) and 11 PR (58%), with an overall response rate of 63%, with 2 more patients having MR (see also Table 4). Afterward, imatinib dosage has been modified as follows: 1 patient reduced the dose to 50 mg per day because of fluid retention; in 2 patients dosage was increased to 200 mg per day, whereas in the remaining patients imatinib was maintained at 100 mg per day. After 6 months of treatment, 5 patients converted from PR to CR, and 1 more patient converted from NR to CR; the patient in CR after 3 months of imatinib maintained the CR, the overall CR rate being 37% (7 of 19). The remaining 6 patients in PR maintained this response at 6 months, and 2 more patients converted from NR or MR to PR, leading to an overall PR rate of 42% (8 of 19). The overall response rate (CR + PR) at 6 months was 79%. After 6 months of treatment, among the 8 patients who had previously been treated with rituximab, we observed 2 CRs and 6 PRs; among the 11 patients who had not received rituximab before imatinib, the response rate was 64%, with 5 CRs and 2 PRs. In 10 patients, imatinib treatment allowed that steroids were stopped or tapered off or their dosage significantly reduced (see Table 4). It is remarkable that 2 patients (UPNs 310AR and 1992MP) with severe lung involvement and who depended on oxygen were able to discontinue oxygen administration. At last follow-up, among the responding patients, 11 are still on imatinib therapy. In the long term, 2 more patients discontinued imatinib, because of subjective intolerance (represented in both cases by mild symptoms such as myalgia and fluid retention) and 1 patient for MM relapse (all these 3 patients maintained a stable response); one had died of leukemia relapse. The details of response after 3 and 6 months, considering each organ involved, are reported in Tables 5 and 6.

Outcome

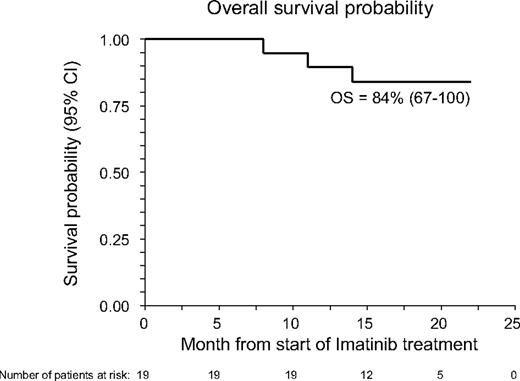

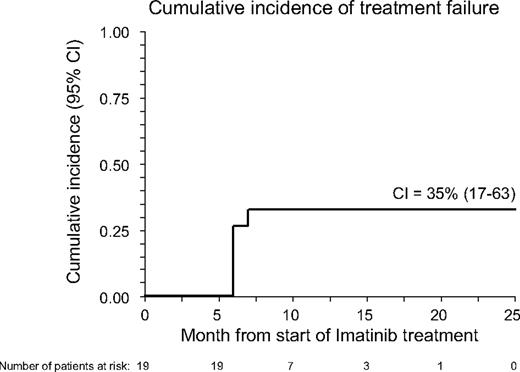

With a median follow-up of 17 months (range, 8-22 months), 16 patients are alive, 14 still maintaining benefit from imatinib treatment (6 in CR and 8 in PR); 1 more patient maintains MR with a stable disease. The 18-month Kaplan-Meier estimate of OS calculated from the inception of imatinib is 85% (95% confidence interval, 67%-100%; see also Figure 1), whereas the CI of TF was 35% (95% confidence interval, 17%-63%; see also Figure 2). Three patients died: one with AML (UPN 1) had leukemia relapse while completely responding to imatinib and died because of disease progression; one (UPN 1064) died because of secondary neoplasia (DLCL); a third patient (UPN 99 992), who had a previous history of lung infections consequent to cGVHD and its treatment, died because of pneumonia. At time of death, this patient was receiving steroids plus cyclosporine. No further unexpected SAEs have been observed during the late follow-up of patients still on Imatinib treatment.

Overall survival probability (OS) of the 19 patients with cGVHD receiving imatinib. OS was measured from start of imatinib treatment.

Overall survival probability (OS) of the 19 patients with cGVHD receiving imatinib. OS was measured from start of imatinib treatment.

Cumulative incidence (CI) of treatment failure in the 19 patients with cGVHD receiving imatinib. CI was calculated from the start of imatinib to whichever event was considered as treatment failure (intolerance or lack of response).

Cumulative incidence (CI) of treatment failure in the 19 patients with cGVHD receiving imatinib. CI was calculated from the start of imatinib to whichever event was considered as treatment failure (intolerance or lack of response).

Discussion

Treatment options for patients developing cGVHD are limited and often unsatisfactory; steroids can be effective, but many patients have a suboptimal response and are unable to discontinue steroids even after months or years of therapy. The addition of a calcineurin inhibitor may be of benefit, allowing to reduce the dosage of steroids used, with a consequent lower risk of steroid-related toxicity, but it proved to be unable to reduce transplantation-related mortality among patients with chronic GVHD.4 Similarly, the addition of other agents to the combination of steroids plus calcineurin inhibitors has still not definitively proved to significantly ameliorate the long-term outcome of patients with steroid-resistant cGVHD.5

In view of these findings, it is not surprising that there is no standard approach for patients with cGVHD refractory to steroids, and these patients are entitled to experimental treatment protocols based on innovative approaches, able to interfere with alloautoreactive response at the basis of chronic GVHD, as well as with the mechanisms responsible for the development of fibrosis.25,26 Blockade of PDGF or TGF-β signaling has been shown to reduce the development of fibrosis in various experimental models.15-17 However, agents that selectively inhibit PDGF pathways are not yet available for clinical application. Similarly, human antibodies against TGF-β did not show clinical efficacy in patients with SSc.27

In view of in vitro data showing that imatinib mesylate exerts selective, dual inhibition of the TGF-β/PDGF pathways,17 we conducted a prospective study evaluating safety and activity of imatinib mesylate in a series of patients affected by refractory cGVHD, with fibrotic/sclerotic features. In our cohort, all patients enrolled in the study had previously failed at least 2 lines of therapy (including steroids in all 19 patients, RTX, ECP, mofetil mycophenolate, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide; see Table 1 for details). Although our patients were heavily pretreated, most of them responded to imatinib treatment, showing either CR or PR, and the OS probability at 18 months from imatinib inception was 84%. These results compare favorably with other salvage therapies, which, in similar settings, obtained very low response rates,6,9,28 except for the series by Jacobsohn et al29 who reported a response rate of 55% with Pentostatin and for that reported by Couriel et al8 who obtained 61% response rate with ECP. Jacobsohn et al29 prospectively enrolled 53 patients who had failed first-line therapy, whereas Couriel et al8 retrospectively evaluated 71 patients with severe cGVHD (8 heavily pretreated, with > 3 lines of immunosuppression, including steroids). Both studies showed an encouraging outcome with an OS of 53% at 1 year with ECP (but only of 19% at 5 years) and a 2-year OS of 70% with Pentostatin. The beneficial role played by ECP in patients with cGVHD has also been confirmed in a recently published randomized trial documenting that it may have a steroid-sparing effect, concomitant with improvement in skin disease.7

A limitation of our study may be represented by the criteria of inclusion we chose; indeed, in view of the notion that imatinib is a potent antifibrotic drug, we enrolled only patients with fibrotic/sclerotic features cGVHD. Therefore, it remains to be tested whether imatinib mesylate can be effective also in patients with cGVHD without these clinical features. However, it should be emphasized that most patients in our series had not only extensive skin fibrosis, but also many of them had other systemic manifestations, such as lung involvement, sicca syndrome, or gut involvement.

Considering the degree of pathologic damage present in many patients with fibrotic features of cGVHD, and the mechanism of action of this antifibrotic drug presumably associated with a response slower than that achievable with immunosuppressive drugs, we decided to have 2 relatively late time points of evaluation of efficacy, namely 3 and 6 months after imatinib inception, to be able to observe a late clinical improvement in the organs involved by the fibrotic process. Indeed, most patients converted from NR to PR or from PR to CR after 3 more months of treatment, suggesting that in the absence of response an early discontinuation of the treatment could be premature or even detrimental.

In our protocol we used prospectively defined objective response criteria, and the follow-up of our patients exceeds the short-term outcomes recommended for phase 2 studies by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference on cGVHD.25 We used the response criteria proposed by Couriel et al,8 integrated by some recommendations proposed by the recent NIH Consensus Conference on cGVHD,21 which permit a more stringent/precise evaluation of response in specific organs. Unfortunately, as reported in the NIH Consensus Conference document, no validated scale exists for assessing sclerotic skin changes of cGVHD, and more sophisticated skin-specific scores are warranted. A comprehensive scale has been proposed by NIH to evaluate also other nonfibrotic skin lesions, but it has not yet been validated in prospective clinical trials; only one recent study retrospectively used the NIH response criteria.30 Because the secondary end point of our study was the response rate in patients with fibrotic/sclerotic features, we quantified the skin fibrotic response by using an mRSS.22 The validity of this mRSS as a semiquantitative method has been supported by findings of a series of studies in patients with systemic sclerosis.31 For the response in organs other than the skin, we generally observed a response also in those patients showing involvement of the respiratory tract and of the GI tract. Notably, we also observed an unexpected improvement of sicca syndrome, which, so far, has been considered an irreversible sequela. It is tempting to speculate that imatinib treatment resulted in a reversion of the fibrosis of the lachrymal gland, permitting a better production of tears, as suggested by the improvement observed in the Schirmer test. However, this peculiar aspect deserves further and more specific investigations.

The toxicity profile of imatinib in this study was acceptable. The young age of most of our patients and the significantly lower dosage of imatinib, compared with the 400 mg per day, usually administered to patients with CML possibly contributed to this safety profile. This said, the good response rate observed suggests that, in this subset of patients, imatinib could be effective even at a low dose such as 100 mg per day. The toxicities of concern were represented by the well-known fluid retention associated with imatinib treatment, whereas the fatalities we observed cannot be reasonably attributed to imatinib treatment. As mentioned earlier, one patient developed a secondary DLCL, and 2 patients showed a relapse of the original malignancy (MM and AML) after imatinib therapy. Secondary neoplasia and disease relapse/progression are not infrequent among patients with cGVHD, who require continuous immunosuppressive therapy, potentially impairing the mechanisms of antitumor immune surveillance. However, we cannot definitively exclude that imatinib has played a role as additive immunosuppressive agent, as suggested by some reports.32

In conclusion, this preliminary experience indicates that low-dose imatinib is active and tolerated in patients affected by cGVHD with sclerotic features and that the responses obtained are sustained over time, resulting in an encouraging patient outcome, as proved by the 18-month OS of 84%. Moreover, a number of steroid-dependent patients were able to either reduce or even discontinue steroids. Our results support the conduction of further confirmatory studies with low-dose tyrosin-kinase inhibitors in patients with refractory cGVHD. In this line, a multicenter prospective Italian study aimed at confirming these data is ongoing.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Presented in part (preliminary data in 15 patients) in poster form at 2008 Annual Meeting of the European Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), Florence, Italy, March 2008.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partially by grants from AIRC (Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro), CNR (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche), MURST (Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica), European Union (FP6 program ALLOSTEM), Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo (F.L.), and Azienda Ospedaliera San Carlo.

Authorship

Contribution: A.O., A.B., and A.G. conceived and designed the study; F.L., M.Z., A.S., P.L., G.G., R.R., N.M., and A.B. provided study materials or patients; M.C. and A.O. collected and assembled data; A.O., F.L., A.B., and M.C. analyzed and interpreted data; and A.O., F.L., and A.B. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Attilio Olivieri, UOC di Ematologia-Centro Trapianto di Cellule Staminali, Azienda Ospedaliera Regionale San Carlo, via Potito Petrone 1, Potenza, 85100 Italy; e-mail: attilio.olivieri@ospedalesancarlo.it.

References

Author notes

*F.L. and A.B. contributed equally to this study.