To the editor:

In recent years the antibody-independent functions of B cells have gained increasing attention. B cells can become potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) after activation. Contrary to activated B cells, resting B cells can act as immunoregulatory cells. Two interesting recent papers in Blood now show that activated human B lymphocytes can also obtain regulatory functions. The fact that activated B cells can inhibit T-cell responses is somewhat surprising, as we and others have shown that B cells stimulated via CD40 induce CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in vitro and in vivo.1-3 How can these discrepancies be explained?

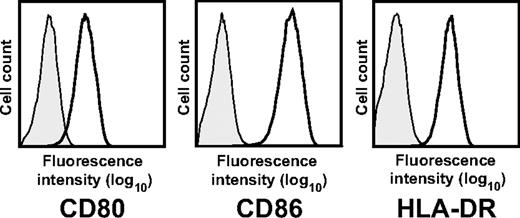

Tretter et al show that activation by Staphylococcus aureus Cowan I (SAC) or CpG-containing oligonucleotides induces B cells which down-regulate T-cell responses by inducing anergy and apoptosis of CD4+ T cells in an IL-2–dependent fashion.4 The suppressive effect was restricted to the activated large B-cell subpopulation expressing the high-affinity interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor CD25. CD25 expression is not a marker for B cells with regulatory function, though, because many other stimuli, including CD40 activation and IL-4, also induce CD25 expression. Like the regulatory B-cell population described by Tretter et al, CD40-activated B cells express CD25 as well as high levels of costimulatory molecules (Figure 1). Despite these similar features, they do activate T cells even in the presence of 50 U/mL IL-2, a concentration at which Tretter et al observed an inhibition of T-cell proliferation.1,3 Therefore, the functional consequences of CD25 expression on activated B cells appear to be dependent on the activation stimulus. Bacterial activation by stimuli such as CpG, SAC, and lipopolysaccharide5 seem to confer regulatory functions whereas activation via CD40 induces stimulatory functions in B cells exposed to IL-2.1,5 In addition, because SAC preferentially activates; immunoglobulin variable heavy chain gene 3 (VH3)–expressing B cells, it could be that suppressive function is characteristic for this subpopulation of B cells.6

Phenotype of CD40-activated B cells. Surface expression of CD80, CD86, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR of CD19+ CD40-activated B cells. Results are representative of more than 50 experiments.

Phenotype of CD40-activated B cells. Surface expression of CD80, CD86, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR of CD19+ CD40-activated B cells. Results are representative of more than 50 experiments.

It has previously been shown that murine and human resting B cells can expand regulatory T cells in vitro.7,8 Tu et al demonstrate that alloantigen-specific human regulatory T cells can be generated in vitro using autologous CD40-activated (CD40-B) cells.9 The CD40-B cells seem to be more heterogeneous than typical CD40-B cells, though (Figure 1). Based on the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II, 2 distinct populations represented by 2 separate peaks can be identified in Figure 1C of their article. Because Tu et al used cryopreserved CD40-B cells, the process of cryopreservation and thawing might have affected the function of the CD40-B cells.

In conclusion, these 2 studies exemplify the activation state–dependent plasticity of B-cell function. Several factors such as the type, duration, and strength of the activation stimulus, the B-cell subset, and microenvironmental setting seem to determine the final outcome. The role of different modes of B-cell activation in determining B-cell function therefore requires further clarification. One should thus be cautious before drawing general conclusions about the function of activated B cells from studies that use only a limited set of activation stimuli.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alexander Shimabukuro-Vornhagen, University Hospital of Cologne, Kerpener Strasse 62, Cologne, Germany 50924; e-mail: alexander.shimabukuro-vornhagen@uk-koeln.de.