Abstract

Annexin A5 (AnxA5) is a potent anticoagulant protein that crystallizes over phospholipid bilayers (PLBs), blocking their availability for coagulation reactions. Antiphospholipid antibodies disrupt AnxA5 binding, thereby accelerating coagulation reactions. This disruption may contribute to thrombosis and miscarriages in the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). We investigated whether the antimalarial drug, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), might affect this prothrombotic mechanism. Binding of AnxA5 to PLBs was measured with labeled AnxA5 and also imaged with atomic force microscopy. Immunoglobulin G levels, AnxA5, and plasma coagulation times were measured on cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells and a syncytialized trophoblast cell line. AnxA5 anticoagulant activities of APS patient plasmas were also determined. HCQ reversed the effect of antiphospholipid antibodies on AnxA5 and restored AnxA5 binding to PLBs, an effect corroborated by atomic force microscopy. Similar reversals of antiphospholipid-induced abnormalities were measured on the surfaces of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and syncytialized trophoblast cell lines, wherein HCQ reduced the binding of antiphospholipid antibodies, increased cell-surface AnxA5 concentrations, and prolonged plasma coagulation to control levels. In addition, HCQ increased the AnxA5 anticoagulant activities of APS patient plasmas. In conclusion, HCQ reversed antiphospholipid-mediated disruptions of AnxA5 on PLBs and cultured cells, and in APS patient plasmas. These results support the concept of novel therapeutic approaches that address specific APS disease mechanisms.

Introduction

The antiphospholipid (aPL) syndrome (APS), an autoimmune thrombophilic disorder, is believed to affect approximately 10% of patients who have vascular thrombosis1 and approximately 20% of patients with recurrent spontaneous pregnancy losses.2 Prevention of recurrent thrombosis in APS requires long-term anticoagulant therapy,3 a treatment associated with the risk of hemorrhagic complications.3 The elucidation of specific mechanisms by which antiphospholipid antibodies may promote thrombosis may be useful for targeting treatment to earlier steps in the APS disease process.

The aPL antibody-mediated disruption of the annexin A5 (AnxA5) anticoagulant shield is a thrombogenic mechanism for APS for which substantial evidence has accumulated.4 AnxA5, which had been isolated from tissues as a vascular anticoagulant protein5 and as a placental anticoagulant protein,6 exhibits high affinity for anionic phospholipids.5,6 Its potent anticoagulant properties result from its forming 2-dimensional crystals over phospholipid bilayers,7 thereby shielding them from availability for critical coagulation enzyme reactions.5 aPL antibodies interfere with AnxA5 binding,8-11 and with its ordered crystallization,12 thereby accelerating coagulation reactions.8,12 This aPL antibody-mediated reduction of AnxA5 has also been demonstrated on placental trophoblasts,13-15 endothelial cells,14,16 and platelets.8,11 The interference with AnxA5 anticoagulant activity has been correlated with aPL antibodies that recognize a specific epitope on domain I of β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI),17 considered to be the central protein recognized by aPL antibodies18 , which is associated with increased risk of thrombosis. Assays of blood samples for AnxA5 binding8,9,11,19,20 and anticoagulant activity8,20,21 showed significant reductions in patients with APS and thrombosis, and also in patients with histories for recurrent pregnancy losses.22

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is a synthetic antimalarial compound that has proven to be an effective immunosuppressive treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).23-26 A reduction in the frequency of thrombosis among SLE patients treated with HCQ was first suggested more than 20 years ago27 and buttressed by further evidence in patients with SLE28-30 and APS.30,31 The Hopkins Lupus Cohort reported that the presence of aPL antibodies is an independent predictor of thrombosis in SLE, and that treatment of SLE patients with HCQ was associated with a reduced risk of thrombosis.28 A cross-sectional study that compared aPL antibody–positive patients with thrombosis with a group of patients having the antibodies, but who did not have thrombotic histories, indicated that HCQ may be protective against thrombosis.31 An observational study of a prospective cohort of SLE patients reported a strong and independent antithrombotic effect of antimalarials in a time-varying Cox model.32 Another prospective study of patients in a lupus clinic who did not have a prior history of thrombotic manifestations indicated that aPL positivity was a risk factor for thrombosis with a hazard ratio of 5.87 for subsequent thrombosis compared with the aPL-negative SLE patients, and that treatment with HCQ reduced the hazard ratio for thrombosis/month to 0.99;30 interestingly, the risk of thrombosis was also reduced in the aPL-negative group. A recent systematic review of the literature on antimalarial treatment in SLE concluded that there was moderate evidence for protection against thrombosis.33 The drug significantly reduced the extent of experimentally provoked thrombosis in an animal model of APS,34 and also reversed aPL-mediated platelet activation.35 We recently demonstrated that HCQ reduces the binding of aPL immunoglobulin G (IgG)–β2GPI complexes to phospholipid bilayers, and through atomic force microscopic (AFM) imaging studies, that the drug can disintegrate aPL-β2GPI complexes.36

These effects of HCQ prompted us to investigate whether the drug might protect the binding of AnxA5 from disruption by aPL IgG-β2GPI. We investigated this question with purified proteins and phospholipids, with cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), with a cultured syncytialized trophoblast cell (STC) line, and with human APS plasma samples.

Methods

Reagents

The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Montefiore Medical Center, which granted permission for the use of excess plasmas from APS patients that had been obtained from clinical assays or plasmapheresate discards, and were anonymized. Polyclonal IgG antibodies were isolated with protein G from citrated plasma of 3 well-characterized patients with severe APS and 3 disease-free controls, as previously described.14 The 3 APS IgGs, at the concentration that was used for the experiments described below, that is 0.5 mg/mL, were assayed for anticardiolipin IgG, anti-β2GPI IgG, and lupus anticoagulant with standard clinical laboratory tests. All had elevated anticardiolipin IgG levels (61-84 GPL units), and elevated anti-β2GPI IgG levels (60-155 GPL units); 2 of the 3 IgGs had positive lupus anticoagulant tests by standard dilute Russell viper venom time assays performed with mixing and confirmatory steps. A human aPL monoclonal IgG antibody (mAb), designated IS4, was purified as previously described.37 This well-characterized mAb was selected because it is purified and highly specific, qualities necessary for high resolution of AFM imaging. IS4 recognizes β2GPI and anionic phospholipid37 and does not exhibit lupus anticoagulant activity, as measured by dilute Russell viper venom time or kaolin clotting time.37,38 A human IgG derived from patients with monoclonal gammopathies (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a control. Purified human β2GPI (Intracel) showed a single band at 50 kDa in sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis electrophoresis and Western blot. AnxA5 purified from human placenta was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Oregon green-conjugated AnxA5 (OG-AnxA5) was purchased from Invitrogen. A stock solution of HCQ (gift of Dr Kirk Sperber, Mount Sinai School of Medicine) was prepared with N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid–buffered saline (HBS; 0.01M N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 0.14M NaCl, pH 7.5) at 200 mg/mL and stored at 4°C.

Effect of HCQ on AnxA5 binding

Phospholipid bilayers composed of 30% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (PS) and 70% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC; Avanti Polar Lipids) were formed on reflective silicon slides, as previously described,12 and transferred to cuvettes containing 1 mL of HBS supplemented with 0.05% bovine serum albumin and 1.25mM calcium for studies described below.

We performed the following experiment to determine whether HCQ might modify the effects of aPL IgGs on AnxA5 binding to phospholipid. Solutions containing each of the 3 aPL or 3 control IgGs (0.5 mg/mL), β2GPI (5 μg/mL), unlabeled AnxA5 (5 μg/mL), and OG-AnxA5 (5 μg/mL) were incubated with HCQ (1 mg/mL) or buffer control for 30 minutes at room temperature before contact with the phospholipid bilayers. Protein adsorptions were monitored with a thin film ellipsometer (Rudolph & Sons). Supernatants were sampled (25 μL) into a microtiter plate filled with 100 μL/well HBS, 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 0.05% bovine serum albumin; OG-AnxA5 fluorescence was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths 485 nm and 535 nm, respectively, using a SpectraMax GEMINI XS microplate spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices).

To investigate whether HCQ might affect the affinity of AnxA5 itself for the phospholipid bilayers, HCQ (1 mg/mL) or buffer control was added to the bilayer; aliquots of unlabeled AnxA5 were added serially (up to 10 μg/mL), after the prior addition had reach equilibrium. Based on the measured free AnxA5 and the total amount of AnxA5 added to the bilayer, traditional graphs plotting phospholipid-bound AnxA5 versus free AnxA5 were generated. Using SigmaPlot software (SPSS), Langmuir isotherms were fit simultaneously to binding data to determine a Kd in the absence of HCQ, a Kd in the presence of 1 mg/mL HCQ, and a maximum binding capacity independent of HCQ.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell cultures

Tissue-culture materials and reagents were obtained from Life Technologies, unless otherwise specified. HUVECs were isolated from umbilical cords, and the second passage of primary HUVECs was immortalized by overexpression of murine telomerase reverse transcriptase.39 The cells were maintained in culture medium consisting of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2mM l-glutamine, and 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics for studies described below. CD31 and vascular endothelial cadherin staining were detected, and functional assays of endothelial cells were confirmed for cells up to 15 passages.

HUVECs were seeded at densities of 8 × 104 cells/well in 96-well culture plates and grown to confluence.14 Cells were rinsed with HBS-CaCl2 buffer and incubated with human aPL or control IgGs (0.5 mg/mL), supplemented with HCQ or control buffer, in the medium for 2 hours with 1 mg/mL HCQ or 5 hours with 1 μg/mL HCQ. The cells were then maintained at 4°C to inhibit the recycling of membranes and vesicles. Trypan blue exclusion studies demonstrated that the IgG-treated HUVECs were at least 95% viable. Measurements of IgG and AnxA5 on cell membranes and plasma coagulation assays were performed, as described below. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate for each IgG.

STC cultures

A human trophoblast cell line (BeWo) obtained from ATCC was used for these experiments, as it was previously shown to respond to aPL IgG in a manner equivalent to primary syncytialized placental trophoblasts.14,15 Cells maintained in 90% Ham F12K medium with 2mM glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 10% fetal bovine serum were plated at densities of approximately 9 × 104 cells/well in 96-well culture plates.14 After 5 hours, they were syncytialized via addition of forskolin (20μM; Sigma-Aldrich) and maintained with daily feeding for up to 72 hours.15 These syncytialized trophoblast cells (STCs), were rinsed with HBS-CaCl2 and then treated with aPL or control IgG, in the absence or presence of HCQ, as described above for HUVECs. Trypan blue exclusion studies demonstrated that the IgG-treated STCs were at least 95% viable. Measurements of IgG and AnxA5 on cell membranes and plasma coagulation assays were performed, as described below. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate for each IgG.

Effects of HCQ on cell-surface IgG and AnxA5 levels

To determine the quantities of IgG bound to the cell surfaces, aPL and control IgG-treated HUVECs or SCTs, in the presence and absence of HCQ at 2 concentrations (1 μg/mL and 1 mg/mL), were rinsed with HBS, incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti–human IgG (Corgenix) for 60 minutes at 4°C, rinsed twice with HBS, and incubated with tetramethyl benzidine substrate for 30 minutes at room temperature. The reactions were stopped by addition of sulfuric acid. The optical absorbances were measured at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 650 nm; results were read against a standard curve using phosphatidylserine-coated microtiter plates (REAADS Medical Products) and reported as arbitrary aPS IgG units per well (AU/well).

Cell-surface AnxA5 levels were determined after the IgG-treated HUVECS and STCs were rinsed with HBS-CaCl2 (to prevent dissociation of endogenous AnxA5), as previously described.14

Effects of HCQ on cell-surface plasma coagulation

Studies were performed with cultured HUVECs and STCs as previously described,14 with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were grown to confluence in 96-well culture plates, rinsed with HBS-CaCl2, and incubated at 4°C with aPL or control IgGs (0.5 mg/mL) in culture media with or without HCQ, as described above. After 1 wash with HBS-CaCl2, the cells were overlaid with citrated normal pooled plasma (200 μL/well), which was recalcified with 20mM CaCl2. The culture plates were placed in a kinetic microtiter plate reader (SPECTRAmax Plus 384; Molecular Devices) at 37°C, and the times until fibrin formation were measured; fibrin formation was detected by an increase of optical density to 0.100 at 405 nm.

Effects of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant activity

Excess citrated plasmas from 10 patients that had been used for clinical assays and anonymized were stored at −80°C and used for these assays. The plasma samples were selected on the basis of positive assays for AnxA5 resistance that were performed in the Hematology Laboratory of Montefiore Medical Center, as described in the paragraph below. The patients included 7 women and 3 men who ranged in age from 17 to 54 years, with the following clinical aspects (total more than 10 because of patients with more than 1 manifestation): 1 patient with catastrophic APS who also had deep vein thrombosis, 4 other patients with venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism, 2 patients with arterial thrombosis, 3 patients with recurrent spontaneous miscarriages, 1 patient with preeclampsia, and 1 patient with ulcerative colitis. Two of the patients had SLE and were therefore defined as having secondary APS. All had elevated anticardiolipin and anti-β2GPI IgG antibodies along with positive lupus anticoagulant by international consensus criteria.40

A modified 2-stage method was used to determine the effects of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant activity of these plasmas, as previously described.17,20 Briefly, test plasmas (50 μL) with HCQ (1 mg/mL) or control buffer (HBS) were incubated with reagent composed of recombinant human tissue factor (Innovin; Dade Behring) and activated partial thromboplastin time reagent phospholipids (actin FSL [Dade Behring] at 1:1 ratio) containing 10mM EDTA for 30 minutes at room temperature. The plasmas were centrifuged with a microcentrifuge (Eppendorf centrifuge 5417R; Brinkmann Instruments) for 15 minutes at 20 800g at 25°C. Pellets were washed in HBS and resuspended in the buffer (220 μL) with HCQ (1 mg/mL) or buffer alone. After incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature, the suspensions (50 μL) were transferred to a ST4 coagulation instrument (American Bioproducts) and incubated with pooled normal plasma (50 μL) for 30 seconds at 37°C. CaCl2 (20mM) alone (50 μL) or 20mM CaCl2 containing AnxA5 (30 μg/mL) was added, the coagulation times were determined, and the mean times of duplicate tests were recorded. The anticoagulant activity of AnxA5 was calculated, as described:17,20 AnxA5 anticoagulant ratio = (coagulation time in the presence of AnxA5/coagulation time in the absence of AnxA5) × 100%.

AFM imaging studies

AFM experiments were performed to visualize the structures formed by AnxA5, β2GPI, and aPL mAb, IS4 on phospholipid bilayers (30% PS and 70% PC), as previously described.12,36 Two types of experiments, referred to as end point and dynamic imaging experiments, were performed. In end point imaging experiments,12 the proteins AnxA5 (60 μg/mL), β2GPI (10 μg/mL), and IS4 (10 μg/mL) in 150 μL of HBS containing 1.25mM CaCl2 (HBS-CaCl2) were incubated with the bilayer for 2.5 hours in the absence or presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL), after which imaging was performed. The dynamic imaging experiments12 were performed to elucidate the sequential development of structures observed in the end point experiments. For these studies, β2GPI (10 μg/mL) in 150 μL of HBS with 1.25mM CaCl2 was first added to the bilayers and incubated overnight at 4°C to allow the β2GPI clusters to form, as previously described.36,41 The next morning, continuous imaging of the lipid bilayer was initiated, and AnxA5 (60 μg/mL) and IS4 (10 μg/mL) were added sequentially, in the absence or presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL). EDTA (2.2mM) was added at the end of experiments to confirm the dissociation of AnxA5, for which binding is calcium dependent. The order of addition was also modified wherein IS4 (10 μg/mL) was first added to allow immune complexes to form, after which HCQ (1 mg/mL) and AnxA5 (60 μg/mL) were added, followed, at the end of the experiment, by EDTA (2.2mM).

Adsorption of proteins was observed using “tapping mode” imaging with a Digital Instruments BioScope (Nanoscope IIIa controller; Veeco) using either oxide-sharpened silicon nitride pyramidal probes (Advanced Surface Microscopy) or Budget Sensor Silicon Nitride Twin Tip probes with Cr/Au reflex coating (Ted Pella).12

Statistical analysis

Results of measurements obtained in the absence and presence of HCQ, that is IgG levels, AnxA5 levels, plasma coagulation times, and AnxA5 anticoagulant ratios, were compared using paired 2-tailed t test (Instat program; GraphPad). Differences between the treatments of aPL versus control groups were analyzed using unpaired 2-tailed t tests. P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of HCQ on aPL IgG-mediated reduction of AnxA5 binding

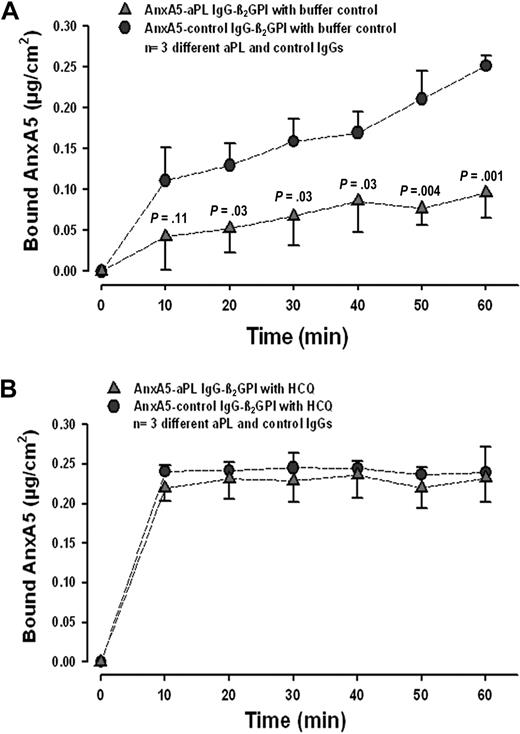

We first investigated whether HCQ might modify the reduction of AnxA5 binding that is induced by aPL IgGs. In accordance with previous results,8-10,12-14,20,42 we found that aPL IgGs, in the absence of HCQ, significantly reduced the binding of AnxA5 to phospholipids (Figure 1A). In the presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL), binding of AnxA5 was restored to the same levels observed with control IgGs (Figure 1B). The acceleration of AnxA5 binding by HCQ with control IgG, that is even in the absence of aPL IgG, was a reproducible finding.

HCQ reverses aPL-mediated reduction of AnxA5 binding to phospholipid bilayers. (A) In the absence of HCQ, aPL IgGs (0.5 mg/mL) significantly reduced the binding of AnxA5 to PS/PC bilayers (quantity measured at 60 minutes: 0.10 ± 0.03 μg/cm2 compared with 0.25 ± 0.01 μg/cm2 for control IgG and β2GPI; n = 3 pairs of different IgGs; P = .001). P values on graph denote differences between aPL and control IgGs (0.5 mg/mL). (B) In the presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL), binding of AnxA5 was restored to levels that were equivalent to control IgG (quantity measured at 60 minutes: 0.23 ± 0.03 μg/cm2 vs 0.24 ± 0.03 μg/cm2 for controls; P = .71). Interestingly, the presence of HCQ accelerated the binding of AnxA5 with control IgG, that is, even in the absence of aPL IgG.

HCQ reverses aPL-mediated reduction of AnxA5 binding to phospholipid bilayers. (A) In the absence of HCQ, aPL IgGs (0.5 mg/mL) significantly reduced the binding of AnxA5 to PS/PC bilayers (quantity measured at 60 minutes: 0.10 ± 0.03 μg/cm2 compared with 0.25 ± 0.01 μg/cm2 for control IgG and β2GPI; n = 3 pairs of different IgGs; P = .001). P values on graph denote differences between aPL and control IgGs (0.5 mg/mL). (B) In the presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL), binding of AnxA5 was restored to levels that were equivalent to control IgG (quantity measured at 60 minutes: 0.23 ± 0.03 μg/cm2 vs 0.24 ± 0.03 μg/cm2 for controls; P = .71). Interestingly, the presence of HCQ accelerated the binding of AnxA5 with control IgG, that is, even in the absence of aPL IgG.

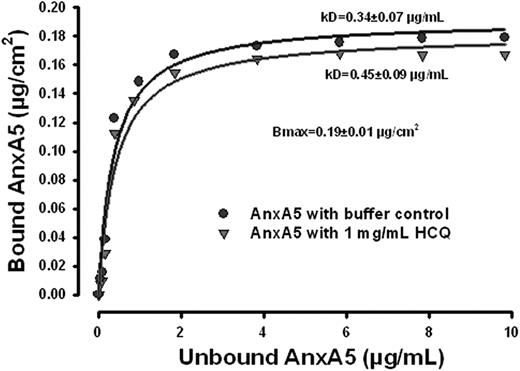

Studies of HCQ interaction with AnxA5

We then investigated whether the restoration of AnxA5 binding by HCQ might be explained by an increase in the affinity of AnxA5 for phospholipid bilayers. The results of the binding isotherms of AnxA5 to phospholipid bilayer (Figure 2) demonstrate that the binding affinity was not increased. The maximum binding density of AnxA5 was 0.19 plus or minus 0.01 μg/cm2 (P < .001), and the equilibrium constant, Kd, for the AnxA5-phospholipid interaction was 0.34 plus or minus 0.07 μg/mL. In the presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL), the binding of AnxA5 was modestly decreased, with a modest, but statistically significant increase of the equilibrium constant, Kd, to 0.45 plus or minus 0.90 μg/mL, compared with the Kd in the absence of HCQ (P < .001; Figure 2). Thus, the increase of AnxA5 binding in the presence of aPL IgGs that is induced by HCQ is not a consequence of increased affinity for phospholipid bilayers.

HCQ does not increase AnxA5 binding to phospholipid bilayers. AnxA5-binding isotherm without and with HCQ. The binding affinity of the protein was not increased, and even modestly reduced by HCQ. There was a modest but statistically significant increase of Kd in the presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL), compared with the buffer controls.

HCQ does not increase AnxA5 binding to phospholipid bilayers. AnxA5-binding isotherm without and with HCQ. The binding affinity of the protein was not increased, and even modestly reduced by HCQ. There was a modest but statistically significant increase of Kd in the presence of HCQ (1 mg/mL), compared with the buffer controls.

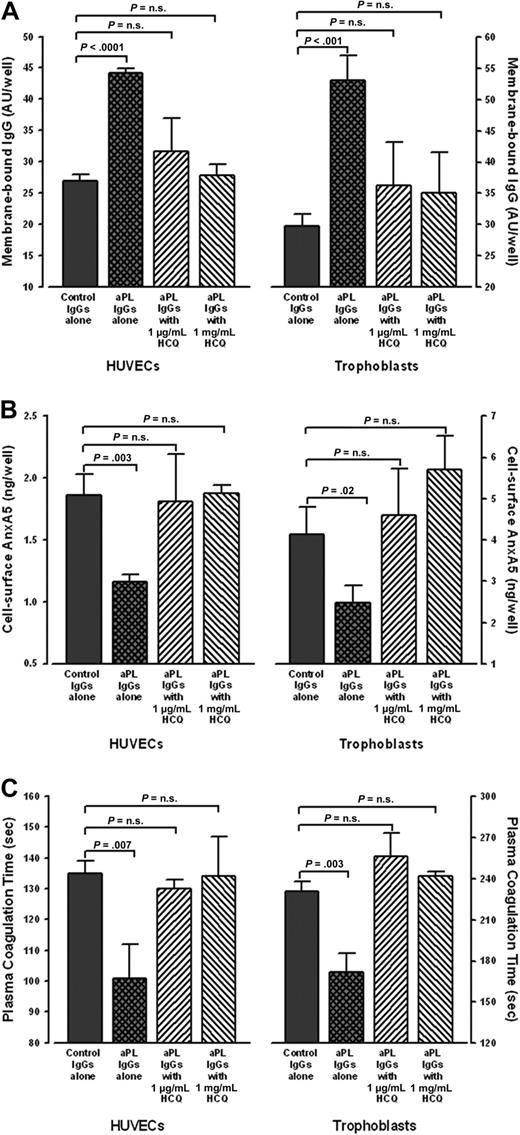

Studies with cultured cell lines

Cultured HUVECs and STCs that were exposed to aPL IgGs bound significantly more IgG than cells exposed to control IgGs (Figure 3A). HCQ significantly reduced aPL IgG binding to levels similar to control IgGs (Figure 3A). In addition, aPL IgG-treated cells had significantly less AnxA5 bound to their surfaces than control IgG-treated cells (Figure 3B), as previously reported.14 Addition of HCQ significantly increased the levels of AnxA5 on aPL IgG-treated HUVECS and STCs to similar levels observed with control IgG (Figure 3B). We then investigated whether the HCQ-mediated increase of cell surface AnxA5 might correlate with prolongation of the coagulation times of plasmas exposed to these cells. As previously reported,14 the coagulation times of plasma overlaid on aPL IgG-exposed cells were significantly accelerated compared with control IgGs in the absence of HCQ (Figure 3C). However, the addition of HCQ reversed the acceleration, and prolonged the coagulation times to levels that were not significantly different from control IgGs (Figure 3C). In addition, in the presence of HCQ, there were no significant differences in IgG levels, AnxA5 levels, or coagulation times between aPL IgG-treated cells and the control IgG-treated cells (data not shown).

HCQ reduced bindings of aPL IgG, increased quantity of AnxA5, and reversed the acceleration of plasma coagulation on cultured HUVECs and STCs. (A) HCQ reduced binding of aPL IgGs to cultured cells. In the absence of HCQ, HUVECs (left panel) exposed to human aPL IgGs (0.5 mg/mL) bound significantly more IgG than with control IgGs (44.2 ± 0.7 AU/well vs 26.9 ± 1.1 AU/well; P < .001); HCQ significantly reduced the binding of aPL IgGs to the surfaces of HUVECs (31.5 ± 5.2 AU/well for HCQ at 1 μg/mL and 27.8 ± 1.8 AU/well for HCQ at 1 mg/mL) to levels that were not significantly different from control IgGs (26.9 ± 1.1 AU/well;P = .19 and P = .50, respectively). Similarly, STCs (right panel) exposed to human aPL IgGs (0.5 mg/mL) bound significantly more IgG than with control IgGs (53.0 ± 4.0 AU/well vs 29.8 ± 1.8 AU/well; P < .001); HCQ significantly reduced the binding of aPL IgGs to the surfaces of STCs (36.2 ± 7.0 AU/well for HCQ at 1 μg/mL and 35.0 ± 6.6 AU/well for HCQ at 1 mg/mL) to levels that were not significantly different from control IgGs (29.8 ± 1.8 AU/well; P = .20 and P = .26, respectively). There were no significant differences between control IgGs in the absence or presence of both concentrations of HCQ (data not shown). As described in “Human umbilical vein endothelial cell cultures” and “STC cultures,” 3 pairs of IgGs from APS patients and controls were used for all of these experiments, done in quadruplicate for each IgG. (B) HCQ increased AnxA5 levels on cultured HUVECs and STCs exposed to aPL IgGs. In the absence of HCQ, aPL reduced AnxA5 levels compared with control IgG (1.2 ± 0.1 ng/well vs 1.9 ± 0.2 ng/well; P = .003); HCQ increased AnxA5 levels on the aPL IgG-treated cells to levels similar to control IgGs (1.8 ± 0.4 ng/well for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 1.9 ± 0.1 ng/well for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 1.9 ± 0.2 ng/well for control IgG; P = .85 and P = .88, respectively). The same effect was seen with STCs, wherein aPL IgG reduced AnxA5 (2.5 ± 0.4 ng/well vs 4.1 ± 0.7 ng/well for control IgGs; P = .02), and HCQ increased the AnxA5 to levels similar to control IgGs (4.6 ± 1.1 ng/well for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 5.7 ± 0.8 ng/well for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 4.1 ± 0.7 ng/well; P = .57 and P = .06, respectively). There were no significant differences between control IgGs in the absence or presence of both concentrations of HCQ (data not shown). (C) HCQ reversed the acceleration of coagulation times of plasmas overlaid on cultured HUVECs and STCs exposed to aPL IgGs. The coagulation times of plasma on aPL IgG-treated HUVECs (left panel) were significantly accelerated compared with control IgGs (101 ± 11 seconds vs 135 ± 4 seconds; P = .007). HCQ significantly prolonged them to coagulation times that were not significantly different from control IgGs (130 ± 3 seconds for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 134 ± 13 seconds for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 135 ± 4 seconds for control IgGs; P = .15 and P = .90, respectively). The same effect was seen with STCs (right panel), wherein the coagulation times of plasma overlaid on aPL IgG-treated cells were significantly accelerated (172 ± 14 seconds vs 231 ± 7 seconds for control IgGs; P = .003). HCQ significantly prolonged them to coagulation times that were not significantly different from control IgGs (256 ± 17 seconds for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 242 ± 3 seconds for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 231 ± 7 seconds for control IgG; P = .08 and P = .07, respectively). There were no significant differences between control IgGs in the absence or presence of both concentrations of HCQ (data not shown).

HCQ reduced bindings of aPL IgG, increased quantity of AnxA5, and reversed the acceleration of plasma coagulation on cultured HUVECs and STCs. (A) HCQ reduced binding of aPL IgGs to cultured cells. In the absence of HCQ, HUVECs (left panel) exposed to human aPL IgGs (0.5 mg/mL) bound significantly more IgG than with control IgGs (44.2 ± 0.7 AU/well vs 26.9 ± 1.1 AU/well; P < .001); HCQ significantly reduced the binding of aPL IgGs to the surfaces of HUVECs (31.5 ± 5.2 AU/well for HCQ at 1 μg/mL and 27.8 ± 1.8 AU/well for HCQ at 1 mg/mL) to levels that were not significantly different from control IgGs (26.9 ± 1.1 AU/well;P = .19 and P = .50, respectively). Similarly, STCs (right panel) exposed to human aPL IgGs (0.5 mg/mL) bound significantly more IgG than with control IgGs (53.0 ± 4.0 AU/well vs 29.8 ± 1.8 AU/well; P < .001); HCQ significantly reduced the binding of aPL IgGs to the surfaces of STCs (36.2 ± 7.0 AU/well for HCQ at 1 μg/mL and 35.0 ± 6.6 AU/well for HCQ at 1 mg/mL) to levels that were not significantly different from control IgGs (29.8 ± 1.8 AU/well; P = .20 and P = .26, respectively). There were no significant differences between control IgGs in the absence or presence of both concentrations of HCQ (data not shown). As described in “Human umbilical vein endothelial cell cultures” and “STC cultures,” 3 pairs of IgGs from APS patients and controls were used for all of these experiments, done in quadruplicate for each IgG. (B) HCQ increased AnxA5 levels on cultured HUVECs and STCs exposed to aPL IgGs. In the absence of HCQ, aPL reduced AnxA5 levels compared with control IgG (1.2 ± 0.1 ng/well vs 1.9 ± 0.2 ng/well; P = .003); HCQ increased AnxA5 levels on the aPL IgG-treated cells to levels similar to control IgGs (1.8 ± 0.4 ng/well for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 1.9 ± 0.1 ng/well for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 1.9 ± 0.2 ng/well for control IgG; P = .85 and P = .88, respectively). The same effect was seen with STCs, wherein aPL IgG reduced AnxA5 (2.5 ± 0.4 ng/well vs 4.1 ± 0.7 ng/well for control IgGs; P = .02), and HCQ increased the AnxA5 to levels similar to control IgGs (4.6 ± 1.1 ng/well for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 5.7 ± 0.8 ng/well for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 4.1 ± 0.7 ng/well; P = .57 and P = .06, respectively). There were no significant differences between control IgGs in the absence or presence of both concentrations of HCQ (data not shown). (C) HCQ reversed the acceleration of coagulation times of plasmas overlaid on cultured HUVECs and STCs exposed to aPL IgGs. The coagulation times of plasma on aPL IgG-treated HUVECs (left panel) were significantly accelerated compared with control IgGs (101 ± 11 seconds vs 135 ± 4 seconds; P = .007). HCQ significantly prolonged them to coagulation times that were not significantly different from control IgGs (130 ± 3 seconds for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 134 ± 13 seconds for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 135 ± 4 seconds for control IgGs; P = .15 and P = .90, respectively). The same effect was seen with STCs (right panel), wherein the coagulation times of plasma overlaid on aPL IgG-treated cells were significantly accelerated (172 ± 14 seconds vs 231 ± 7 seconds for control IgGs; P = .003). HCQ significantly prolonged them to coagulation times that were not significantly different from control IgGs (256 ± 17 seconds for 1 μg/mL HCQ and 242 ± 3 seconds for 1 mg/mL HCQ vs 231 ± 7 seconds for control IgG; P = .08 and P = .07, respectively). There were no significant differences between control IgGs in the absence or presence of both concentrations of HCQ (data not shown).

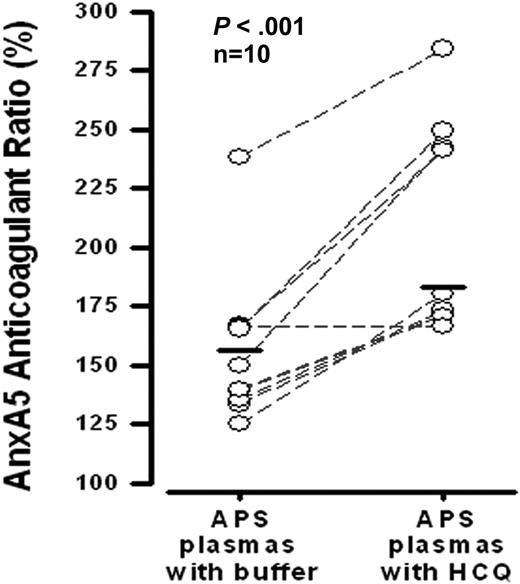

Effect of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant ratio

HCQ significantly increased the mean AnxA5 anticoagulant ratio of APS plasmas (Figure 4). Nine of the 10 plasmas that were tested demonstrated this effect.

Effects of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant activity of plasmas from APS patients. HCQ (1 mg/mL) significantly improved the AnxA5 anticoagulant activities of APS plasmas that were exposed to the same concentration (30 μg/mL) of AnxA5 (183 ± 45% vs 156 ± 33% without HCQ; P < .001). This assay, described in “Effects of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant activity,” and previously,14 is a coagulation assay that measures the effect of test plasma on the binding of AnxA5 to phospholipids present in a prothrombin time-activated partial thromboplastin time reagent.

Effects of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant activity of plasmas from APS patients. HCQ (1 mg/mL) significantly improved the AnxA5 anticoagulant activities of APS plasmas that were exposed to the same concentration (30 μg/mL) of AnxA5 (183 ± 45% vs 156 ± 33% without HCQ; P < .001). This assay, described in “Effects of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant activity,” and previously,14 is a coagulation assay that measures the effect of test plasma on the binding of AnxA5 to phospholipids present in a prothrombin time-activated partial thromboplastin time reagent.

AFM imaging studies

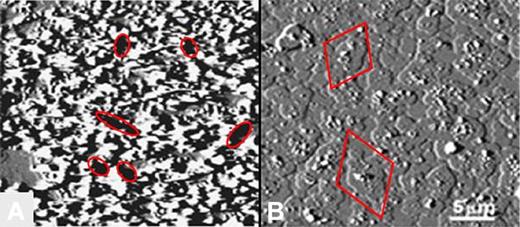

In the absence of HCQ, the AnxA5 crystalline array was markedly disrupted by aPL mAb-β2GPI immune complexes (Figure 5A), as previously described.12 Addition of HCQ (1 mg/mL) resulted in coverage of the entire surface with cobblestone-like patches of AnxA5 around and over the former aPL mAb-β2GPI complexes (Figure 5B). HCQ had no discernible direct effect on the phospholipid bilayer; that is, in the absence of added proteins, there were no changes in the appearance of the PS/PC surface (data not shown).

End point AFM imaging of effects of HCQ on AnxA5 crystallization. (A) In the absence of HCQ, aPL mAb with β2GPI markedly disrupted the normally smooth AnxA5 crystalline array, as previously described.7,12 The dark zones present throughout the image (6 of which are demarcated by ellipses) indicate markedly decreased height measurements that are consistent with exposure of phospholipid bilayer (size range 0.5-2 μm), 6 of which are demarcated by ellipses.7,12 (B) Addition of HCQ prevented this marked disruption of AnxA5 crystallization and resulted in a cobbled surface that is entirely covered by patches of AnxA5 (size range 1.5-4.5 μm; 2 of which are demarcated by diamonds).

End point AFM imaging of effects of HCQ on AnxA5 crystallization. (A) In the absence of HCQ, aPL mAb with β2GPI markedly disrupted the normally smooth AnxA5 crystalline array, as previously described.7,12 The dark zones present throughout the image (6 of which are demarcated by ellipses) indicate markedly decreased height measurements that are consistent with exposure of phospholipid bilayer (size range 0.5-2 μm), 6 of which are demarcated by ellipses.7,12 (B) Addition of HCQ prevented this marked disruption of AnxA5 crystallization and resulted in a cobbled surface that is entirely covered by patches of AnxA5 (size range 1.5-4.5 μm; 2 of which are demarcated by diamonds).

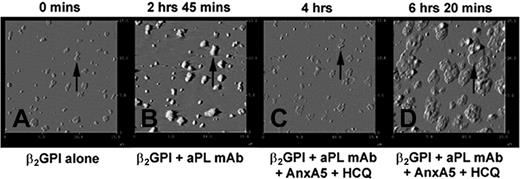

To observe the sequential formation of the AnxA5 patches shown above, experiments were performed with stepwise additions of β2GPI, aPL mAb, HCQ, and AnxA5 (Figure 6A-D). Addition of β2GPI resulted in formation of clusters (Figure 6A), as previously described.36,41 The subsequent addition of the aPL mAb resulted in formation of immune complexes that increased the heights and sizes of these clusters (Figure 6B), as previously described.36 Subsequent addition of HCQ and AnxA5 resulted in erosion of the immune complexes (Figure 6C) and the growth of patches of AnxA5 over the former aPL IgG-β2GPI clusters (Figure 6D). These patches assumed cobblestone-like appearances that were identical to those observed in the end point experiments shown in Figure 5B.

Dynamic AFM imaging of effects of HCQ on AnxA5 crystallization.(A) The binding of β2GPI to phospholipid bilayer after overnight incubation at 4°C resulted in formation of clusters of the protein. An arrow indicates one of these clusters as a representative reference point for the subsequent sequences. (B) The binding of aPL mAb, IS4, to β2GPI clusters showing the formation of aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes with increased heights and thickening of each of the clusters (arrow). (C) Addition of HCQ and AnxA5 resulted in the erosion of the complexes (arrow), as previously described, and (D) formation of “cobblestones” of Anx A5 that formed over and around the remnants of the aPL mAb-β2GPI complexes (arrow). The appearances of the AnxA5 patches are identical to the formations shown in the endpoint experiment of Figure 5B. All above 15 μm × 15-μm amplitude images were electronically zoomed from an original 30 μm × 30-μm scan.

Dynamic AFM imaging of effects of HCQ on AnxA5 crystallization.(A) The binding of β2GPI to phospholipid bilayer after overnight incubation at 4°C resulted in formation of clusters of the protein. An arrow indicates one of these clusters as a representative reference point for the subsequent sequences. (B) The binding of aPL mAb, IS4, to β2GPI clusters showing the formation of aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes with increased heights and thickening of each of the clusters (arrow). (C) Addition of HCQ and AnxA5 resulted in the erosion of the complexes (arrow), as previously described, and (D) formation of “cobblestones” of Anx A5 that formed over and around the remnants of the aPL mAb-β2GPI complexes (arrow). The appearances of the AnxA5 patches are identical to the formations shown in the endpoint experiment of Figure 5B. All above 15 μm × 15-μm amplitude images were electronically zoomed from an original 30 μm × 30-μm scan.

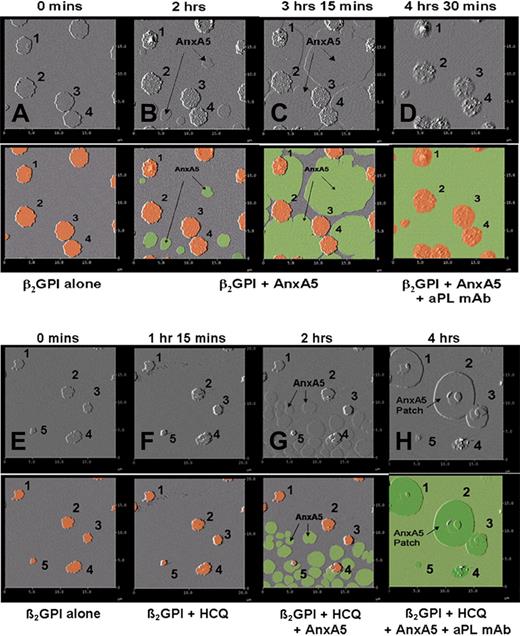

The sequential formation of the AnxA5 patches was further visualized by stepwise additions of β2GPI, followed by AnxA5 and then aPL mAb, performed in the absence and presence of HCQ (Figure 7A-H). Addition of β2GPI resulted in formation of clusters of the protein (Figure 7A), as previously described.36,41 The subsequent addition of AnxA5, in the absence of HCQ, resulted in the growth of individual crystals of AnxA5 on the phospholipid bilayer, arising from different nucleation sites (Figure 7B), that coalesced into a single layer of AnxA5 over the phospholipid surface (Figure 7C-D), as previously described.7,12 The addition of the aPL mAb resulted in its binding to the surfaces of the β2GPI clusters (Figure 7D). However, when HCQ was present in the system, the coalescence of growing AnxA5 crystals from the initial nucleation sites into the primary layer of the 2-dimensional crystal (Figure 7G) was followed by the formation of secondary layers of AnxA5 crystals over β2GPI clusters, which grew progressively (Figure 7H) and had a similar morphologic appearance to the AnxA5 patches that were observed in the previous experiments (Figures 5B and 6D). The identity of the secondary layers of protein as AnxA5 was confirmed by their dissociation after addition of EDTA (data not shown).

Dynamic AFM imaging of HCQ-induced formation of formation of AnxA5 layer over aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes. Each original AFM amplitude image (top panel) is paired with a colorized version (bottom panel) for explanation. In a sequence performed without HCQ, (A) the addition of β2GPI to phospholipid bilayers resulted in the formation of clusters (marked 1-4, orange circles in colorized version), as previously described.41 (B) Addition of AnxA5 resulted in the initiation of 2-dimensional crystallization (flat round structures, green in colorized version) arising from different nucleation points, which (C) enlarge, merge, and grow toward each other, as previously described,7 until they covered all of the bilayer not occupied by the β2GPI cluster. (D) Subsequently added aPL mAb bound to the surfaces of β2GPI clusters. In a sequence that included HCQ, (E) addition of β2GPI to phospholipid bilayers and formation of β2GPI clusters (marked 1-5) were followed by (F) addition of HCQ, followed by (G) addition of AnxA5, which at first crystallized from multiple different nucleation sites on the phospholipid bilayer, (H) and then formed a secondary layer of AnxA5 over the β2GPI, which progressively grew around and over the adjacent primary layer of AnxA5 crystal, leaving none of the surface uncovered by AnxA5.

Dynamic AFM imaging of HCQ-induced formation of formation of AnxA5 layer over aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes. Each original AFM amplitude image (top panel) is paired with a colorized version (bottom panel) for explanation. In a sequence performed without HCQ, (A) the addition of β2GPI to phospholipid bilayers resulted in the formation of clusters (marked 1-4, orange circles in colorized version), as previously described.41 (B) Addition of AnxA5 resulted in the initiation of 2-dimensional crystallization (flat round structures, green in colorized version) arising from different nucleation points, which (C) enlarge, merge, and grow toward each other, as previously described,7 until they covered all of the bilayer not occupied by the β2GPI cluster. (D) Subsequently added aPL mAb bound to the surfaces of β2GPI clusters. In a sequence that included HCQ, (E) addition of β2GPI to phospholipid bilayers and formation of β2GPI clusters (marked 1-5) were followed by (F) addition of HCQ, followed by (G) addition of AnxA5, which at first crystallized from multiple different nucleation sites on the phospholipid bilayer, (H) and then formed a secondary layer of AnxA5 over the β2GPI, which progressively grew around and over the adjacent primary layer of AnxA5 crystal, leaving none of the surface uncovered by AnxA5.

Discussion

The results of prior clinical studies indicating that HCQ may have a beneficial effect in reducing thrombosis in SLE and APS,27-33 along with evidence from an animal model,34 previously led us to investigate the direct effects of HCQ on aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes.36 The findings that HCQ can disintegrate aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes and reduce the binding of the individual proteins as well as the complexes to phospholipid bilayers36 prompted us to now ask whether the drug might also protect AnxA5 from displacement by aPL antibodies.

The results of the present study showed that HCQ restored the binding of AnxA5 to phospholipids to the levels of control IgGs (Figure 1A-B). We performed formal binding studies to address the question of whether the drug might increase the affinity of AnxA5 for the phospholipid bilayer and found this not to be the case. Rather, the drug induced a modest, but statistically significant reduction in the affinity of AnxA5 (Figure 2), while increasing the binding of the protein in the presence of aPL IgGs (Figure 1B). It is interesting that the binding of AnxA5 was reproducibly accelerated in the presence of HCQ even in the presence of the control IgG (Figure 1B). The mechanism for the latter observation is not yet clear and is a subject for additional investigation in our laboratory.

The HCQ-mediated restoration of AnxA5 was not limited to phospholipid bilayers, but was also evident on cultured HUVECs and STCs, in which the drug reversed the aPL IgG-mediated increase in cell-surface IgG levels (Figure 3A), reversed the aPL IgG-mediated decreases in cell-surface AnxA5 levels (Figure 3B), and also prolonged the coagulation times of plasmas overlaid on the cells (Figure 3C).

To obtain an indication of whether the results of these phospholipid-binding studies, cell-culture experiments with polyclonal IgG fractions, and AFM imaging studies with aPL mAb might be generalizable to patients with APS, we examined the effect of HCQ on AnxA5 anticoagulant ratios of APS patients. This assay for resistance to AnxA5 anticoagulant activity is abnormal in patients with APS17,20,21 and in patients with recurrent miscarriages.22 The in vitro addition of HCQ increased the AnxA5 anticoagulant ratios of 9 of the 10 patients tested (Figure 4).

The AFM imaging experiments offered an interesting view on the possible mechanism for this HCQ effect. In the presence of the drug, AnxA5 formed oval patches around and over the aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes, each of which bordered adjoining patches, resulting in a cobblestone appearance that covered what had previously been a highly irregular surface (Figure 5). Sequential experiments indicated that after the formation of the initial 2-dimensional AnxA5 crystals over the phospholipid bilayer, HCQ could promote the formation of a second layer of AnxA5 crystal whose nucleation sites originate around and over β2GPI clusters themselves. These second layers crystallized outward in a circular manner and extended beyond the borders of the clusters over the primary layer of AnxA5. The precise mechanism of this reproducible and fascinating effect, as well as modifications of the orders of addition, and the effects of epitope specific antibodies and structural modifications of the involved proteins are currently a focus of research in our laboratory.

We have previously shown that HCQ unequivocally disrupts aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes by 4 types of methods, including ellipsometry experiments, immunoassays on microtiter plates, immunoassays on cultured cells, and AFM imaging.36 This effect was also evident in the current cell-culture experiments and in the AFM sequence shown in Figure 6. The disruption was not evident in the AFM sequence shown in Figure 7 because of the order of addition of reagents, that is the AnxA5 was allowed to crystallize around the β2GPI complexes before addition of the aPL mAb.

Although these studies suggest that HCQ may exert a direct therapeutic effect in reducing thrombosis, definitive conclusions will require appropriately designed prospective randomized clinical trials. Because there are also significant data indicating that AnxA5 is a placental anticoagulant protein that may play a thrombomodulatory role in maintaining the flow of maternal blood through the placental circulation,13,43,44 it would be interesting to learn whether HCQ might be beneficial in treating women with the pregnancy complications of APS. There have been several reports, most recently reference,45 on the efficacy of this drug for treating pregnant women with SLE and regarding the apparent absence of fetal toxicity. The more than half century of experience with this drug for treating malaria46 and SLE;47 its established profile with respect to adverse effects, toxicities, and drug interactions; and the absence of hemorrhagic risks are some of the factors that would favor its being evaluated for treatment of APS in prospective randomized clinical trials.

The HCQ concentration of 1 μg/mL and greater was used in the cell-culture studies because that was reported to be the mean blood concentration of drug in SLE patients who comply with treatment.48 A concentration of 1 mg/mL was used for the binding and imaging studies with purified proteins and phospholipid bilayers because previous studies had shown the disruption of aPL-β2GPI bilayers to be most evident at that concentration.36 The actual concentrations of HCQ in vivo in the microenvironment that is the presumptive site of action for this mechanism, that is apical surfaces of cell membranes, are not known.

aPL antibodies appear to be highly heterogeneous. Although there is a general consensus that the thrombogenic mechanism(s) of APS involves autoantibody recognition of phospholipid-binding proteins, particularly β2GPI, the specific mechanism(s) that is operative in vivo has not been established, and is likely to be complex and multifactorial. It is very possible that the HCQ-mediated disruption of aPL IgG-β2GPI complexes may also impact on other mechanisms that involve the aPL-β2GPI interaction, examples of which include the triggering of signaling events that lead to a proadhesive and prothrombotic phenotype, acquired resistance to protein C activation, and the activation of complement.49 We plan to address this question in future studies. It should also be noted that other antithrombotic properties of HCQ, for example, its effect on platelet function,34 maybe also contribute to the clinical effects of the drug. Clinical investigators have also explored several other approaches to targeting APS disease mechanisms, including, among others, platelet function inhibitors, statin drugs, immunomodulatory agents, and complement inhibition.50

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that an antimalarial drug, HCQ, can protect the AnxA5 anticoagulant shield from disruption by aPL antibodies on phospholipid bilayers, on the apical membranes of cultured HUVECS and STCs, and in samples of APS patient plasmas. These results demonstrate that it may be possible to target earlier steps in the APS disease process than those addressed by anticoagulant therapy. Appropriately designed clinical trials will be required to validate this concept.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nina Haghi, MS, for preparing the colorized explanatory portion of Figure 7.

This work was supported by grant HL-61331 from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.H.R. conceived the idea, designed the research, analyzed data, and edited the successive drafts of the manuscript; X.-X.W. wrote the initial draft, revised subsequent drafts, performed all of the experiments except for those involving AFM, and performed statistical analyses of the binding, cell-culture, and plasma assay data; A.S.Q. performed AFM experiments and wrote relevant sections; A.W.A. contributed to the endothelial cell experiments, wrote the relevant “Methods” sections, and participated in the final review of the manuscript; P.P.C. prepared and characterized the monoclonal antibody, contributed to relevant “Methods” and “Results” sections, and edited the drafts; J.J.H. contributed to the mathematical analysis of the protein interactions and edited the manuscript; H.A.M.A. contributed to analysis of the binding data, and edited portions of the text; and D.J.T. designed and directed the AFM experiments, and wrote and edited the text.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jacob H. Rand, Core Laboratory Office, Foreman 8, Silver Zone, 111 E. 210th St, Bronx, NY 10467; e-mail: jrand@montefiore.org.