Abstract

Interleukin-7 (IL-7) is an essential cytokine for T-cell development and homeostasis. It is well established that IL-7 promotes the transcriptional down-regulation of IL7RA, leading to decreased IL-7Rα surface expression. However, it is currently unknown whether IL-7 regulates the intracellular trafficking and early turnover of its receptor on ligand binding. Here, we show that, in steady-state T cells, IL-7Rα is slowly internalized and degraded while a significant fraction recycles back to the surface. On IL-7 stimulation, there is rapid IL-7Rα endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits, decreased receptor recycling, and accelerated lysosome and proteasome-dependent degradation. In accordance, the half-life of IL-7Rα decreases from 24 hours to approximately 3 hours after IL-7 treatment. Interestingly, we further demonstrate that clathrin-dependent endocytosis is necessary for efficient IL-7 signal transduction. In turn, pretreatment of T cells with JAK3 or pan-JAK inhibitors suggests that IL-7Rα degradation depends on the activation of the IL-7 signaling effector JAK3. Overall, our findings indicate that IL-7 triggers rapid IL-7Rα endocytosis, which is required for IL-7–mediated signaling and subsequent receptor degradation.

Introduction

Interleukin 7 (IL-7) is a key prosurvival cytokine essential for T-cell proliferation, development, and homeostasis. IL-7 is produced by stromal cells in the thymus and bone marrow, and also by vascular endothelial cells, intestinal epithelium, keratinocytes, and follicular dendritic cells.1 The IL-7/IL-7R signaling network was shown to be critical in health and disease. IL-7 is essential in lymphoid development because knockout mice for IL-7,2,3 IL-7Rα,4 γc,5 and JAK1,6 or JAK37 suffer similar lymphoid developmental blocks. IL-7 was also shown to rescue primary T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells from spontaneous apoptosis in vitro8 and IL-7 transgenic mice develop lymphomas.9 Furthermore, IL-7 may be involved in chronic inflammation, osteoclast maturation, and subsequent bone destruction in rheumatoid arthritis.10

IL-7 signals via the IL-7 receptor, composed by the IL-7Rα and the γ common chain (γc), which is shared by other interleukin receptors, namely, IL-2, IL-4, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21. On ligand binding, IL-7Rα and γc heterodimerize and are phosphorylated by JAK1/3.1 In T cells, this directs the activation of STAT5 and PI3K, leading to cell cycle progression, increased viability, and cell size.1,8,11 In general, effective signal transduction depends on the tight control of receptor membrane trafficking via internalization, degradation, and recycling mechanisms,12 and may occur during receptor trafficking in intracellular vesicles, rather than just at the cell surface.13 Moreover, endocytosis is commonly required for efficient receptor-mediated signal transduction, and it has been described for other cytokine receptors, such as IL-2R14 and IL-5R.15 Receptor endocytosis can occur via clathrin-coated pits and/or clathrin-independent routes. For example, assembly of high-affinity IL-2R and consequent signal transduction is dependent on lipid rafts.14 Interestingly, the different chains of the receptor (α, β, and γc) are differentially sorted after internalization: whereas β and γc chains are targeted for degradation, the α chain internalizes constitutively and recycles back to the surface.16 Other receptors, such as the IL-5R,15 transforming growth factor-β,17 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),18 internalize not only via clathrin-coated pits but also via clathrin-independent routes. Independently of the internalization route, it is thought that receptors traffic to early endosomes, where they can then be sorted for degradation and/or recycling.19,20 Whether an internalized receptor is targeted for degradation or recycling depends on several factors, which differ between receptor and cell type.19 Ubiquitination is usually associated with receptor degradation via proteasomes, but in some cases efficient degradation of ubiquitinated receptor relies on both proteasomes and lysosomes.21,22

Dissecting how IL-7 regulates its cognate receptor membrane trafficking is crucial to the in-depth understanding of the role of IL-7/IL-7R in lymphocyte function. Previous studies have suggested that IL-7 stimulation of T cells leads to surface down-modulation of IL-7Rα within 30 minutes, possibly because of receptor internalization.23 At later time points (2-6 hours), IL-7 was shown to induce transcriptional down-regulation of IL7RA.24-26 However, the actual dynamics of IL-7Rα internalization and the regulation of trafficking mechanisms by IL-7 remain to be elucidated. In the present study, we show that IL-7 induces rapid clathrin-dependent IL-7Rα internalization in human T cells. Moreover, our results suggest that IL-7–induced signaling is dependent on IL-7Rα internalization and that subsequent receptor degradation relies on JAK3 activity and is mediated by both proteasomes and lysosomes. Our study explores, for the first time, the mechanisms of IL-7–induced IL-7Rα trafficking, contributing to the understanding of the biology of the IL-7/IL-7R axis in lymphocyte function.

Methods

Cell line and primary human thymocytes

Human HPB-ALL cell line was cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) culture medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 10mM penicillin-streptomycin solution, and 2mM l-glutamine (hereafter referred to as RPMI 10). Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Human thymocytes were isolated from thymic tissue obtained from children undergoing cardiac surgery. Samples were obtained with informed consent after institutional review board approval from the Hospital de Santa Cruz in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The tissue was gently disrupted in RPMI and filtered through a cell strainer. Thymocytes were enriched by density centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) to at least 95% purity. All cell culture experiments were performed in RPMI 10 with or without 50 ng/mL recombinant human IL-7 (PeproTech).

Cell treatment with inhibitors

When indicated, cells were pretreated or not (vehicle control) with inhibitors at a density of 106 cells/mL, and inhibitors were kept during the duration of the experiment: hyperosmotic sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich; 0.5M; 1-hour pretreatment), monodansylcadaverine (Sigma-Aldrich; 100μM, 1-hour pretreatment), NH4Cl (Sigma-Aldrich; 50mM; 1-hour pretreatment), JAK3 inhibitor WHI-P131 (Calbiochem; 150μM; 1-hour pretreatment), pan-JAK inhibitor I (Calbiochem; 10μM; 1-hour pretreatment), cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich; 500μM, 30-minute pretreatment), lactacystin (Calbiochem; 25μM, 1-hour pretreatment), and filipin (Sigma-Aldrich; 2.5 μg/mL, 1-hour pretreatment).

Flow cytometric analysis

For cell surface assessment of receptor expression, cells were washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after the indicated stimulus/pretreatment, resuspended in PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 30 minutes on ice with α-human IL-7Rα-phycoerythrin-conjugated antibody (clone 40131; R&D Systems), or isotype- and concentration-matched immunoglobulin G (IgG)–phycoerythrin control. Cells were then washed in ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), incubated 15 minutes on ice, and analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (TreeStar). For intracellular assessment of receptor expression, cells were washed in ice-cold PBS after the indicated stimulus/pretreatment, resuspended in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.05M sucrose, and incubated at 4°C for 15 minutes. After fixing, cells were washed in cold PBS as before, resuspended in 50mM NH4Cl in PBS for quenching, and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. After quenching, cells were washed with permeabilization buffer (PBS/1% bovine serum albumin/0.05% saponin), resuspended in permeabilization buffer, and incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. After incubation with antibody for 30 minutes at 37°C, cells were washed in PBS, resuspended in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA), incubated for 15 minutes on ice, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Expression of intracellular and/or surface IL-7Rα was always assessed within the live cell population, as determined by the forward scatter/side scatter distribution.11

Antibody “chase” for assessment of receptor colocalization

For confocal microscopy analysis, the HPB-ALL cell line was plated onto poly-D-lysine (Sigma Aldrich)–coated coverslips for 30 minutes to 1 hour, at 37°C for cells to adhere. To “chase” the pool of surface receptor, cells were incubated in RPMI 10 for 30 minutes on ice with α-human IL-7Rα unconjugated antibody. After primary antibody labeling, cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI 10 and reincubated on ice with α-IgG-Alexa 633 or Alexa 488 (Invitrogen). After washing with PBS, cells were resuspended in RPMI 10 at the density of 106 cells/mL and stimulated or not (vehicle control) with 50 ng/mL IL-7 at 37°C, for the indicated time intervals. After stimulation, cells were washed, fixed, quenched, and permeabilized as for intracellular staining for flow cytometric analysis. Cells were then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in permeabilization buffer with antibodies for different endosomal compartments: clathrin heavy chain fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated (BD Biosciences PharMingen), EEA-1 FITC-conjugated (BD Biosciences PharMingen), lysosome associated membrane protein-2 (LAMP-2) Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated (eBioscience), and rabbit unconjugated Rab-11 (Zymed). When necessary, cells were washed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies: when using FITC-coupled antibodies, α-FITC-Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated antibody (Invitrogen) was used to enhance signal detection. For Rab-11 detection, we used α-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated antibody. After secondary incubation, cells were washed twice in permeabilization buffer and twice in PBS, followed by 10-minute incubation with 4% PFA/sucrose at 4°C. Cells were washed again with PBS, and slides were inverted over a drop of Vectashield/4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories) and sealed with varnish. Slides were analyzed by confocal microscopy, as follows. Image acquisition was performed with the pinhole aperture set to 1 Airy unit for the highest wavelength (633 nm) and adjusted for the lower wavelengths to maintain the same optical slice thickness for all channels. Five to 10 different fields of view (∼ 40 cells per field of view) were collected for quantification, which was performed for a given pair of fluorophores. The percentage of colocalizing cells was determined by counting the fraction of cells showing at least 1 colocalization event (minimum 3 × 3 pixels) between the fluorophores from live cells presenting both fluorophores only (cells in which only 1 of the fluorophores was present were discarded from the analysis).

Antibody feeding and recycling

The HPB-ALL cell line was plated onto poly-D-lysine–coated coverslips as described for colocalization analysis. In parallel, 106 cells were plated on the different condition coverslips. Initially, all cells were incubated at 4°C, in RPMI 10, with unconjugated α-human IL-7Rα antibody for 30 minutes. After this, cells were washed gently 3 times with ice-cold PBS and transferred to 37°C in the presence or absence of IL-7 (50 ng/mL) for antibody feeding for 1 hour. Cells were subsequently washed again, and the positive time zero control coverslip was further incubated at 4°C with secondary α-mouse Alexa 488 antibody, in RPMI 10, for 30 minutes. Cells were fixed at the end with 2% PFA incubation for 15 minutes on ice and washed with PBS. The coverslip was then inverted onto a drop of Vectashield/DAPI as described in “Antibody ‘chase’ for assessment of receptor colocalization.” The negative control is obtained by performing an acid wash (RPMI 10 with pH adjusted to 3), which removes all surface-bound antibody. After the acid wash, the primary antibody/receptor complex was allowed to recycle to the cell surface by switching the cells to 37°C for the indicated time point, in pH 7 RPMI 10 (cells were washed twice with RPMI 10 after acid wash to reestablish normal pH). Recycling is stopped by washing the cells with cold PBS. Recycled IL-7Rα/unconjugated antibody complex is detected by incubating the cells with anti–mouse IgG Alexa 488 secondary antibody for 30 minutes on ice. Slides were analyzed by confocal microscopy, as follows. Measurements of mean fluorescence intensity were performed with the pinhole set to its maximum aperture. This ensures that the fluorescence measured for each cell corresponds to the total surface intensity rather than a single optical slice. At least 8 different fields of view were imaged for each condition (∼ 40 cells per field of view), keeping the same excitation (10% laser transmission) and detection settings throughout the acquisition. Image processing and quantification were performed with ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Briefly, after being background subtracted, each image was thresholded to identify surface fluorescence signals whose mean intensity was then determined for each image. The threshold level was determined based on histogram analysis and was kept constant for each segmentation.

Confocal microscopy

All images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 510 META inverted confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss) using a PlanApochromat 63×/1.4 oil-immersion objective. DAPI fluorescence was detected with a violet 405 nm diode laser (30 mW nominal output) and a BP 420-480 filter. Both enhanced green fluorescence protein and Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence were detected using the 488 nm laser line of an Arg laser (45 mW nominal output) and a BP 505-550 filter. Alexa Fluor 633 fluorescence was detected using a 633 nm HeNe laser (5 mW nominal output) and a custom META detector 636-754 bandpass filter. Transmitted light imaging was performed using 1 of the available laser lines and the transmitted PMT channel available in the LSM 510 META. Sequential multitrack/frame imaging sequences were used to avoid any potential bleed-through from the different fluorophores. All confocal images were acquired with a frame size of 512 × 512 pixels.

Time-lapse microscopy

For live time-lapse imaging, a procedure was used similar to the antibody chase technique and colocalization analysis. However, cells were kept alive throughout the procedure (no fixing or permeabilization). Cells were placed on ice until immediately before imaging, at which point they were transferred to the Zeiss LSM 510 META system equipped with an incubator chamber, where they were kept in a controlled 37°C and 5% CO2 environment. Cells were either imaged unstimulated or after addition of IL-7 (50 ng/mL). A total of 112 images were acquired with a time interval of 30 seconds between each image and 488 nm laser intensity set to 3% to minimize photobleaching. Images were background subtracted and further processed with ImageJ using a rigid body registration algorithm to correct for cell displacement during image acquisition. Movies of cells were then generated and time-annotated.

Immunoblotting

After the indicated conditions and time intervals of culture, cell lysates were prepared, and equal amounts of protein (50 μg/sample) were analyzed by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies: pJAK3 (Sigma-Aldrich), pSTAT5a/b (Upstate Biotechnology), pAKT (Cell Signaling), and actin and ZAP 70 (Upstate Biotechnology). After immunoblotting with antibodies, detection was performed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti–mouse (Promega), anti–rabbit (Promega), or anti–goat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) immunoglobulin (IgG; 1:5000 dilution), as indicated by the host origin of the primary antibody and developed by chemiluminescence.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical analysis was performed using regular 2-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post tests comparing unstimulated VS IL-7 internalization and degradation rates throughout time. When the unstimulated or IL-7–induced internalization or degradation was analyzed on its own, we used regular 1-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post tests. Student t test was used to assess the effect of IL-7 with and without inhibitors, at a selected time point. Differences were considered with statistical significance for P less than .05.

Results

IL-7 induces rapid IL-7Rα internalization in T cells

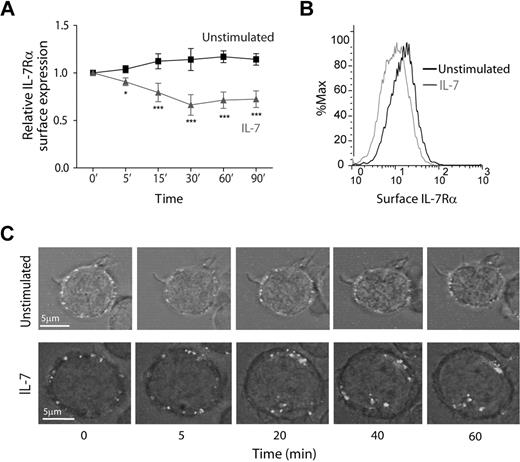

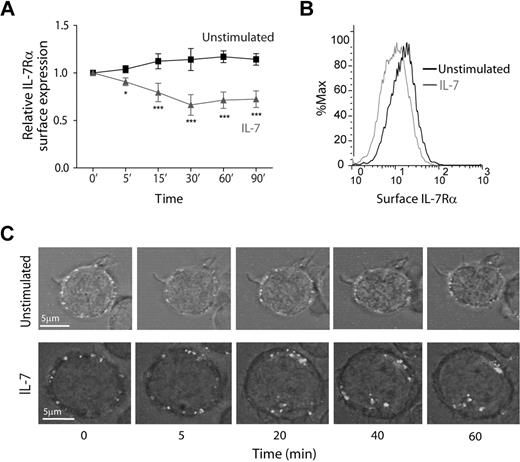

To study the dynamics of IL-7Rα internalization, we started by assessing cell surface expression over time, in the presence or absence of IL-7. Flow cytometric analysis showed that IL-7 induced rapid IL-7Rα surface down-regulation, in normal human thymocytes (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and in the T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines TAIL727 (data not shown) and HPB-ALL (Figure 1), which we used in subsequent experiments. Importantly, we purposely used an antibody that does not compete with IL-7 for IL-7Rα binding (supplemental Figure 2). Interestingly, we found that IL-7Rα surface levels decreased rapidly, with approximately 20% decrease on 5 minutes, 30% after 15 minutes, and 40% after 30 minutes of IL-7 stimulation (Figure 1A-B). This indicates that IL-7–mediated down-regulation of IL-7Rα can occur more rapidly than previously suggested.23,25,26 In addition, rapid IL-7–mediated IL-7Rα surface down-regulation was dose-dependent and clearly observed at doses as low as 1 ng/mL (supplemental Figure 3). To confirm that decreased surface expression was the result of receptor internalization, we stained HPB-ALL cells with an unconjugated mouse anti–IL-7Rα antibody and an anti–mouse Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody on ice to label the IL-7Rα at the surface with minimal receptor internalization.28 This strategy allowed us to follow the pool of surface receptor from a defined stimulation point onwards. Consistent with the flow cytometric data, the levels of surface receptor remained constant when cells were shifted to 37°C in the absence of stimulus, whereas on IL-7 stimulation there were clear receptor clustering and internalization (Figure 1C; supplemental Video).

IL-7 induces rapid IL-7Rα surface down-regulation resulting from receptor internalization. (A) HPB-ALL cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-7 (50 ng/mL) in culture medium for the indicated time points and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry for surface IL-7Rα expression, as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Relative IL-7Rα expression was calculated as the geometric mean intensity of fluorescence normalized to the time 0 control. Data represent mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .001 (1-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni post test). (B) Representative flow cytometric histogram overlay of IL-7Rα surface expression in HPB-ALL cells stimulated for 30 minutes with IL-7 (gray line) or left unstimulated (black line). (C) IL-7Rα internalization visualized by time-lapse microscopy of HPB-ALL cells. IL-7Rα initially expressed at the cell surface was stained with α-human IL-7Rα unconjugated antibody, subsequently reincubated with a secondary α-mouse IgG-Alexa 488–conjugated antibody, and imaged for the indicated time points, with or without addition of IL-7 (50 ng/mL), as described in “Antibody ‘chase’ for assessment of receptor colocalization.” See supplemental data for full time-lapse microscopy video. Representative cells of each condition from 2 independent experiments are shown.

IL-7 induces rapid IL-7Rα surface down-regulation resulting from receptor internalization. (A) HPB-ALL cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-7 (50 ng/mL) in culture medium for the indicated time points and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry for surface IL-7Rα expression, as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Relative IL-7Rα expression was calculated as the geometric mean intensity of fluorescence normalized to the time 0 control. Data represent mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .001 (1-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni post test). (B) Representative flow cytometric histogram overlay of IL-7Rα surface expression in HPB-ALL cells stimulated for 30 minutes with IL-7 (gray line) or left unstimulated (black line). (C) IL-7Rα internalization visualized by time-lapse microscopy of HPB-ALL cells. IL-7Rα initially expressed at the cell surface was stained with α-human IL-7Rα unconjugated antibody, subsequently reincubated with a secondary α-mouse IgG-Alexa 488–conjugated antibody, and imaged for the indicated time points, with or without addition of IL-7 (50 ng/mL), as described in “Antibody ‘chase’ for assessment of receptor colocalization.” See supplemental data for full time-lapse microscopy video. Representative cells of each condition from 2 independent experiments are shown.

IL-7Rα internalization occurs via clathrin-coated pits and is required for IL-7–mediated signaling

Receptor-mediated endocytosis can occur via clathrin-coated pits and/or clathrin-independent routes, such as lipid rafts. Irrespectively of the internalization route, it is thought that internalized receptors traffic to an early endosome antigen 1 (EEA-1)–positive early endosome, where they are sorted for degradation and/or recycling.12,19 IL-2Rα, a cytokine receptor that shares γc with IL-7Rα, was shown to localize to lipid rafts and internalize in a lipid raft-dependent manner.14 We therefore pretreated the cells with filipin, which is known to specifically inhibit lipid raft-dependent internalization,29 and assessed the impact on constitutive and IL-7–dependent IL-7Rα internalization. Our data suggest that the internalization of IL-7Rα is largely independent of lipid rafts (supplemental Figure 4).

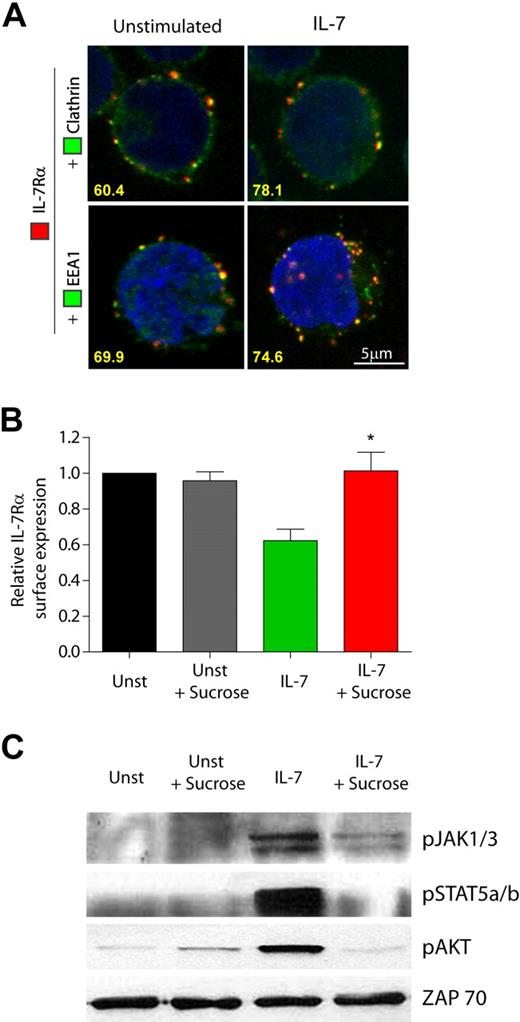

IL-7 can induce phosphorylation of clathrin heavy chain in mouse T-cell precursors,30 highlighting the potential involvement of clathrin in IL-7Rα internalization. To assess this hypothesis, we next analyzed the cellular localization of IL-7Rα, clathrin, and EEA-1 by confocal microscopy, in the absence or presence of IL-7. We found that IL-7Rα and clathrin constitutively colocalized in 60.4% of all the cells analyzed. Similarly, IL-7Rα colocalized with EEA-1–positive endosomes in 69.9% of the cells (Figure 2A). This suggests that IL-7Rα is internalized via clathrin-coated pits and traffics into early endosomes in a constitutive manner. Importantly, after 5 minutes of IL-7 stimulation, IL-7Rα colocalized with clathrin in 78.1% and with EEA-1–positive endosomes in 74.7% of the cells, suggesting that clathrin-dependent internalization into early endosomes rapidly increased in the presence of IL-7 (Figure 2A). To confirm these observations, we pretreated the cells with hyperosmotic sucrose (0.5M), which has been shown to inhibit clathrin-dependent endocytosis.29 IL-7–induced receptor internalization was abrogated by hyperosmotic sucrose pretreatment (Figure 2B), indicating that endocytosis of IL-7Rα relies on clathrin-coated pits. Interestingly, inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, using sucrose or monodansylcadaverine,31 blocked IL-7–induced signaling, as determined by phosphorylation of JAK1/JAK3, STAT5, and Akt/PKB (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 5). These data show that, similarly to other transmembrane receptors,15,18,32 clathrin-dependent endocytosis is required for effective triggering of IL-7–mediated signaling pathways, thereby underlining the functional relevance of IL-7Rα endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits.

IL-7Rα internalization via clathrin-coated pits and trafficking into early endosomes is required for efficient IL-7–mediated signaling. (A) Analysis of IL-7Rα colocalization with clathrin and EEA-1 was performed by confocal microscopy. HPB-ALL cells were plated on poly-D-lysine–coated coverslips, incubated at 4°C with α-human IL-7Rα unconjugated antibody, and subsequently with a secondary α-mouse IgG-Alexa 633 antibody (red). Cells were then shifted to 37°C in the presence or absence of IL-7 (50 ng/mL) for 5 minutes, fixed, quenched, and permeabilized. Endosomal compartments were detected using FITC-conjugated antibodies for clathrin heavy-chain or EEA-1, both enhanced by α-FITC-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (green). The 2 bottom images are 3-dimensional projections and include DAPI-stained nuclei. Representative cells of 3 independent experiments are shown. The percentage of cells that displayed colocalization is indicated and was determined by counting the fraction of cells showing at least 1 colocalization event between red and green fluorescence. (B-C) HPB-ALL cells were pretreated or not with 0.5M sucrose (hypertonic media) for 1 hour, to inhibit formation of clathrin-coated pits, and then stimulated with 50 ng/mL IL-7 or left untreated (Unst) for 30 minutes. (B) IL-7Rα surface expression was analyzed by flow cytometry, and relative expression was calculated by normalizing the geometric mean of fluorescence of the cell population in the presence of IL-7 stimulus, divided by the unstimulated condition. Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments: *P < .05. (C) Immunobloting was performed and IL-7 mediated signaling assessed by detection of phosphorylated JAK1/3, STAT5a/b, and AKT. ZAP-70 was used as a loading control.

IL-7Rα internalization via clathrin-coated pits and trafficking into early endosomes is required for efficient IL-7–mediated signaling. (A) Analysis of IL-7Rα colocalization with clathrin and EEA-1 was performed by confocal microscopy. HPB-ALL cells were plated on poly-D-lysine–coated coverslips, incubated at 4°C with α-human IL-7Rα unconjugated antibody, and subsequently with a secondary α-mouse IgG-Alexa 633 antibody (red). Cells were then shifted to 37°C in the presence or absence of IL-7 (50 ng/mL) for 5 minutes, fixed, quenched, and permeabilized. Endosomal compartments were detected using FITC-conjugated antibodies for clathrin heavy-chain or EEA-1, both enhanced by α-FITC-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (green). The 2 bottom images are 3-dimensional projections and include DAPI-stained nuclei. Representative cells of 3 independent experiments are shown. The percentage of cells that displayed colocalization is indicated and was determined by counting the fraction of cells showing at least 1 colocalization event between red and green fluorescence. (B-C) HPB-ALL cells were pretreated or not with 0.5M sucrose (hypertonic media) for 1 hour, to inhibit formation of clathrin-coated pits, and then stimulated with 50 ng/mL IL-7 or left untreated (Unst) for 30 minutes. (B) IL-7Rα surface expression was analyzed by flow cytometry, and relative expression was calculated by normalizing the geometric mean of fluorescence of the cell population in the presence of IL-7 stimulus, divided by the unstimulated condition. Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments: *P < .05. (C) Immunobloting was performed and IL-7 mediated signaling assessed by detection of phosphorylated JAK1/3, STAT5a/b, and AKT. ZAP-70 was used as a loading control.

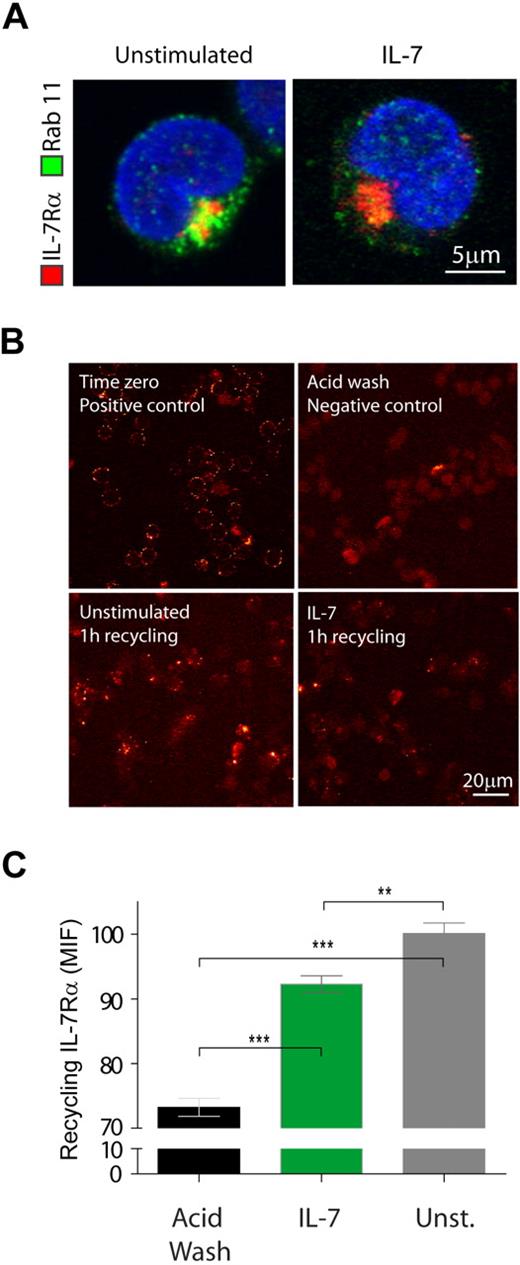

A pool of internalized IL-7Rα constitutively recycles back to the cell surface

Although IL-7Rα constitutively internalized via clathrin-coated pits, the overall surface receptor levels were kept constant, and inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis did not affect the surface receptor levels in the absence of IL-7 (data not shown). These observations raise the possibility that IL-7Rα may constitutively internalize and recycle back to the cell surface. To test this assumption, we assessed whether IL-7Rα colocalized with Rab-11–positive recycling endosomes.33 We found that IL-7Rα colocalized with recycling endosomes both in the absence and presence of IL-7 stimulus, suggesting constitutive recycling of internalized receptor (Figure 3A). Next, we sought to quantify the amount of recycling IL-7Rα in both conditions. To do this, we performed an antibody feeding and recycling assay (adapted from Weber et al34 ), as described in “Antibody feeding and recycling,” in which the amount of antibody found at the surface corresponds to the amount of internalized and subsequently recycled IL-7Rα. The results confirmed that there is constitutive IL-7Rα recycling, which still occurs on IL-7 stimulation, albeit somewhat less efficiently (Figure 3B-C). These data further indicate that there are no major differences in IL-7Rα recycling that could account for decreased surface expression on IL-7 treatment.

A pool of internalized IL-7Rα recycles to the cell surface. (A) Colocalization between IL-7Rα and Rab-11 recycling endosomes was assessed after 5 minutes of stimulation with IL-7 (50 ng/mL). Total IL-7Rα expression was assessed by intracellular staining as for flow cytometry. Rab-11–positive vesicles were further detected by incubation with rabbit α-human Rab-11 unconjugated antibody followed by secondary detection with α-rabbit IgG Alexa 488. Coverslips were mounted over Vectashield/DAPI. Cells representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Colocalization between IL-7Rα and endosomes was performed by antibody chase and colocalization assay, as described in “Antibody ‘chase’ for assessment of receptor colocalization.” Briefly, all cells, plated onto coverslips, were initially incubated at 4°C with unconjugated α-human IL-7Rα antibody for 30 minutes and subsequently washed and transferred to 37°C in the presence or absence of IL-7 (50 ng/mL) for 1 hour to allow for IL-7Rα internalization. Cells were washed, and the positive control (time 0) was generated by incubating the cells at 4°C with α-mouse IgG Alexa 488 secondary antibody for 30 minutes. The remaining coverslips underwent an acid wash treatment to remove surface-bound antibody. The negative control was not further processed. The primary antibody/receptor complex was allowed to recycle to the cell surface in the experimental conditions, by switching the cells to 37°C again for 1 hour. Recycled IL-7Rα/antibody complex was detected by incubating the cells with anti–mouse IgG Alexa 488 secondary antibody for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were fixed, and the different coverslips mounted with Vectashield/DAPI. Representative images of 2 independent experiments are shown for each condition. (C) Microscopy images of the antibody feeding and recycling assays were quantified by determining the mean intensity of fluorescence (MIF) of at least 8 independent fields of view for each condition. **P < .01, ***P < .001 (Student t test, 2-tailed).

A pool of internalized IL-7Rα recycles to the cell surface. (A) Colocalization between IL-7Rα and Rab-11 recycling endosomes was assessed after 5 minutes of stimulation with IL-7 (50 ng/mL). Total IL-7Rα expression was assessed by intracellular staining as for flow cytometry. Rab-11–positive vesicles were further detected by incubation with rabbit α-human Rab-11 unconjugated antibody followed by secondary detection with α-rabbit IgG Alexa 488. Coverslips were mounted over Vectashield/DAPI. Cells representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Colocalization between IL-7Rα and endosomes was performed by antibody chase and colocalization assay, as described in “Antibody ‘chase’ for assessment of receptor colocalization.” Briefly, all cells, plated onto coverslips, were initially incubated at 4°C with unconjugated α-human IL-7Rα antibody for 30 minutes and subsequently washed and transferred to 37°C in the presence or absence of IL-7 (50 ng/mL) for 1 hour to allow for IL-7Rα internalization. Cells were washed, and the positive control (time 0) was generated by incubating the cells at 4°C with α-mouse IgG Alexa 488 secondary antibody for 30 minutes. The remaining coverslips underwent an acid wash treatment to remove surface-bound antibody. The negative control was not further processed. The primary antibody/receptor complex was allowed to recycle to the cell surface in the experimental conditions, by switching the cells to 37°C again for 1 hour. Recycled IL-7Rα/antibody complex was detected by incubating the cells with anti–mouse IgG Alexa 488 secondary antibody for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were fixed, and the different coverslips mounted with Vectashield/DAPI. Representative images of 2 independent experiments are shown for each condition. (C) Microscopy images of the antibody feeding and recycling assays were quantified by determining the mean intensity of fluorescence (MIF) of at least 8 independent fields of view for each condition. **P < .01, ***P < .001 (Student t test, 2-tailed).

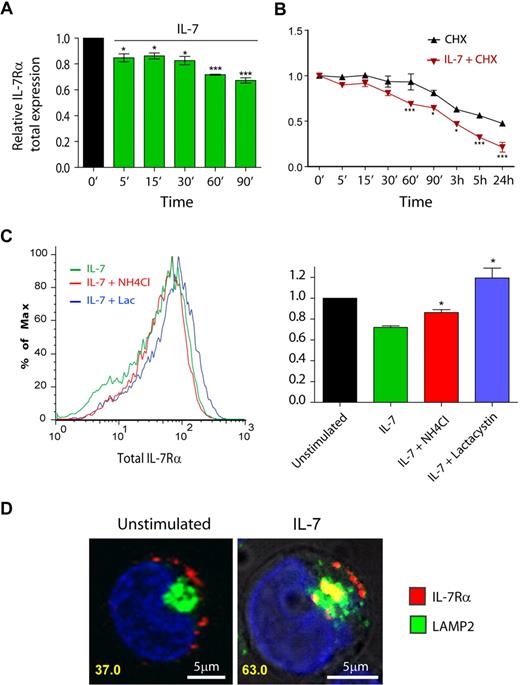

IL-7 induces rapid IL-7Rα degradation in a proteasome- and lysosome-dependent manner

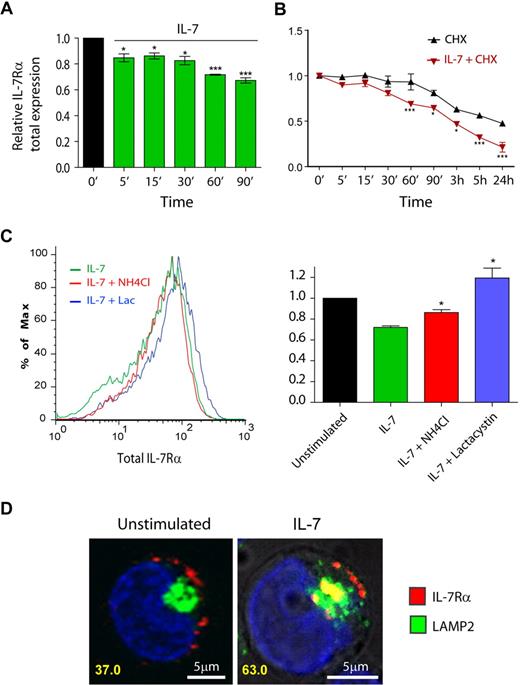

To further characterize the mechanisms involved in IL-7–mediated IL-7Rα surface down-regulation, we next measured the total (surface plus intracellular) receptor levels by flow cytometry. After ensuring that detection of intracellular IL-7Rα by flow cytometry was not affected by unspecific background staining (supplemental Figure 6), we observed rapid down-regulation of IL-7Rα on IL-7 stimulation (Figure 4A). In addition, pretreatment of cells with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide revealed that the kinetics of IL-7Rα degradation was significantly accelerated on IL-7 stimulation (Figure 4B). Accordingly, IL-7Rα half-life was dramatically decreased, from approximately 24 hours in unstimulated cells to approximately 3 hours in the presence of IL-7 (Figure 4B). These data indicate that IL-7–induced rapid IL-7Rα internalization was followed by significant receptor degradation.

IL-7 stimulation accelerates IL-7Rα degradation, in a lysosome and proteasome-dependent manner. (A-C) Total IL-7Rα expression (surface plus intracellular) was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of fixed and permeabilized HPB-ALL cells, as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Analysis of the data was performed as described in Figure 1. *P < .05, ***P < .001 (1-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni post test). (B) To determine IL-7Rα half-life, cells were treated with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). (C) To determine the pathways of degradation of IL-7Rα, cells were pretreated for 1 hour with 50mM NH4Cl or 25μM lactacystin, and then stimulated or not with 50 ng/mL IL-7 for 1 hour. The geometric mean of fluorescence of the population was determined by flow cytometry, as shown in the representative histogram. *P < .05 (Student t test, 2-tailed). Data in panels A, B, and C represent mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments. (D) Colocalization between IL-7Rα and lysosomes in the presence or absence of IL-7 (1 hour; 50 ng/mL) was performed using α-human IL-7Rα antibody and LAMP-2 as a lysosome marker. The percentage of cells that displayed colocalization is indicated and was determined as in Figure 2. Representative cells of 3 independent experiments are shown.

IL-7 stimulation accelerates IL-7Rα degradation, in a lysosome and proteasome-dependent manner. (A-C) Total IL-7Rα expression (surface plus intracellular) was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of fixed and permeabilized HPB-ALL cells, as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Analysis of the data was performed as described in Figure 1. *P < .05, ***P < .001 (1-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni post test). (B) To determine IL-7Rα half-life, cells were treated with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). (C) To determine the pathways of degradation of IL-7Rα, cells were pretreated for 1 hour with 50mM NH4Cl or 25μM lactacystin, and then stimulated or not with 50 ng/mL IL-7 for 1 hour. The geometric mean of fluorescence of the population was determined by flow cytometry, as shown in the representative histogram. *P < .05 (Student t test, 2-tailed). Data in panels A, B, and C represent mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments. (D) Colocalization between IL-7Rα and lysosomes in the presence or absence of IL-7 (1 hour; 50 ng/mL) was performed using α-human IL-7Rα antibody and LAMP-2 as a lysosome marker. The percentage of cells that displayed colocalization is indicated and was determined as in Figure 2. Representative cells of 3 independent experiments are shown.

Protein degradation is thought to occur via 2 main mechanisms in the cell, namely, the ubiquitin-proteasome and the pH-dependent lysosomal degradation pathways.35 To identify the routes of IL-7–induced IL-7Rα degradation, we pretreated the cells with the specific proteasome inhibitor lactacystin36 or the lysosome inhibitor NH4Cl, a lysomotropic agent,34,37 and evaluated total IL-7Rα expression. Our results show that NH4Cl partially reversed, whereas lactacystin completely prevented, IL-7–induced IL-7Rα degradation (Figure 4C). This suggests that both lysosomes and proteasomes participated in the degradation of the receptor. However, because NH4Cl displayed only a partial effect, we sought to further demonstrate the involvement of lysosomes in the degradation of IL-7Rα. We performed receptor “chase” and colocalization experiments using Alexa Fluor 633-labeled anti–IL7-Rα antibody and anti–LAMP-2 Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibody to detect lysosomes.38 As shown in Figure 4D, we found that a significant portion of the receptor localized to lysosomes, after IL-7 stimulation (37% colocalizing cells in unstimulated conditions vs 63% at 1 hour after IL-7 simulation). These results suggest that, after IL-7 stimulation, a considerable fraction of the internalized IL-7Rα pool is degraded by lysosomes, probably in coordination with the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Thus, our data indicate that IL-7 induces IL-7Rα degradation by mechanisms that involve both proteasome and lysosome pathways.

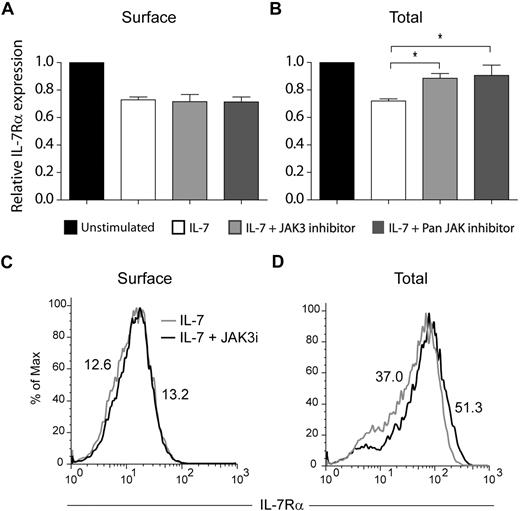

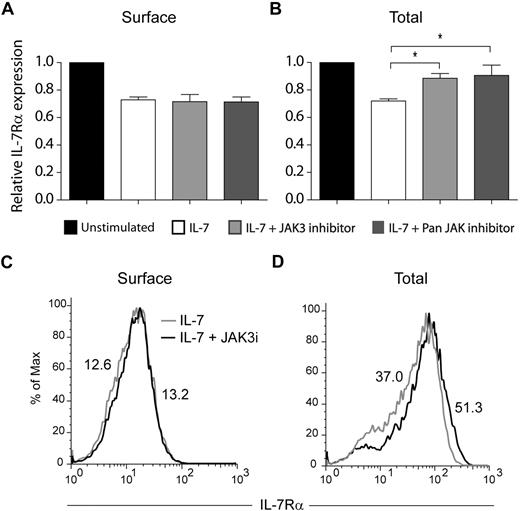

IL-7–induced IL-7Rα degradation relies on JAK3 activity

The JAK family of tyrosine kinases has been previously implicated in the regulation of receptor trafficking.39,40 In addition, IL-7 was shown to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of clathrin heavy chain, possibly via activation of JAK3.30 Therefore, we asked whether JAK kinases, and particularly JAK3, could be involved in IL-7Rα internalization and/or degradation. Pretreatment of HPB-ALL cells with a JAK3-specific inhibitor27 did not prevent IL-7Rα internalization, as determined by the analysis of IL-7Rα surface expression (Figure 5A,C). In contrast, JAK3 inhibition significantly reversed IL-7–induced IL-7Rα degradation (Figure 5B-C). Similar results were obtained using a pan-JAK inhibitor (Figure 5). Taken together, our data suggest that IL-7Rα degradation, but not internalization, is largely dependent on JAK3 activity.

IL-7–induced IL-7Rα degradation, but not internalization, is JAK3 dependent. Surface (A) and total (B) IL-7Rα expression in HPB-ALL cells was assessed by flow cytometry, as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Cells were pretreated with 150μM of JAK3 inhibitor (WHI-P131) or PAN-JAK inhibitor I, and then stimulated or not with IL-7 (50 ng/mL) for 30 minutes (A) or 1 hour (B). The geometric mean of fluorescence for each population was determined by flow cytometry. Data (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 (Student t test, 2-tailed). Representative flow cytometric histogram overlay of surface (C) or total (D) IL-7Rα expression in HPB-ALL cells pretreated (black line) or not (gray line) with the JAK3 inhibitor WHI-P131, followed by IL-7 stimulation for 30 minutes (C) or 1 hour (D).

IL-7–induced IL-7Rα degradation, but not internalization, is JAK3 dependent. Surface (A) and total (B) IL-7Rα expression in HPB-ALL cells was assessed by flow cytometry, as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.” Cells were pretreated with 150μM of JAK3 inhibitor (WHI-P131) or PAN-JAK inhibitor I, and then stimulated or not with IL-7 (50 ng/mL) for 30 minutes (A) or 1 hour (B). The geometric mean of fluorescence for each population was determined by flow cytometry. Data (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 (Student t test, 2-tailed). Representative flow cytometric histogram overlay of surface (C) or total (D) IL-7Rα expression in HPB-ALL cells pretreated (black line) or not (gray line) with the JAK3 inhibitor WHI-P131, followed by IL-7 stimulation for 30 minutes (C) or 1 hour (D).

Discussion

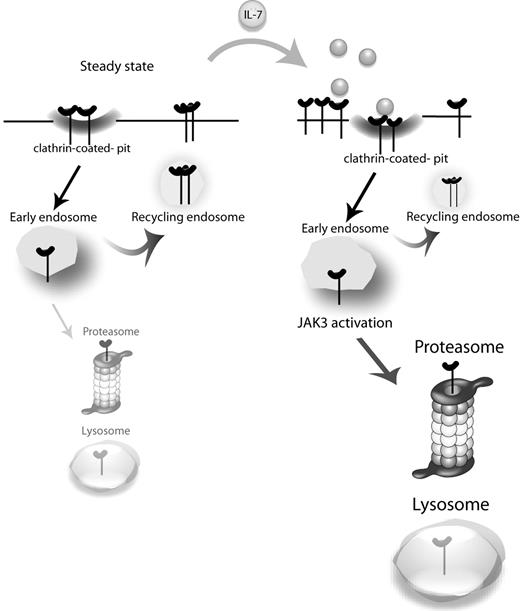

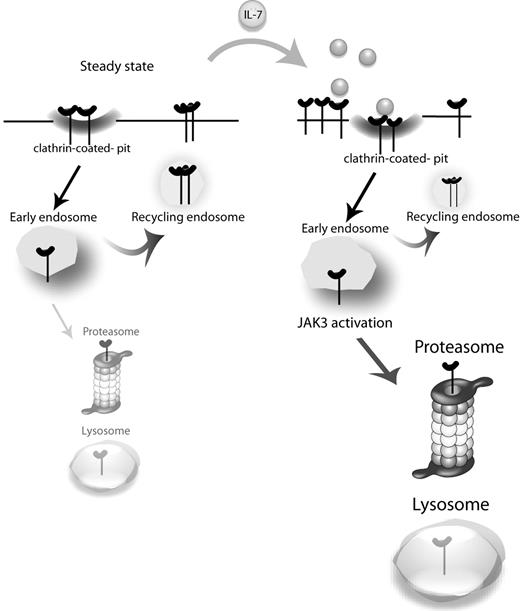

The generalized importance of IL-7 and its receptor for T-cell biology, with critical roles during development, homeostasis, and differentiation, has raised particular interest on how IL-7Rα expression is regulated. It is currently established that IL-7 and other prosurvival cytokines induce the transcriptional down-regulation of IL7RA and consequently decrease significantly the cell surface expression of IL-7Rα at late time points (2-6 hours).24-26 This has been proposed as an altruistic mechanism for optimizing the access of T cells to IL-7, which is expressed at limiting levels.26,41 Here, we focused, for the first time, on the consequences of IL-7 stimulation regarding the early dynamics of IL-7Rα surface expression and associated mechanisms of internalization, recycling, and degradation. We propose that, on a steady-state scenario, IL-7Rα at the cell surface takes part in a slow cycle of constitutive clathrin-dependent internalization and recycling, with a pool of receptor eventually being degraded and replaced by newly synthesized IL-7Rα. On IL-7 stimulation, endocytosis is rapidly accelerated, and the balance is dramatically shifted toward degradation in a manner that is dependent on JAK3 activation, which in turn appears to rely on IL-7Rα being internalized (Figure 6).

Proposed model for IL-7Rα trafficking. At the steady state, IL-7Rα is slowly internalized via clathrin-coated pits and recycled back to the cell surface, with a pool of receptor being degraded and replaced by newly synthesized IL-7Rα (not shown). On IL-7 stimulation, the balance is rapidly shifted toward receptor endocytosis and subsequent degradation. JAK3 activation, which appears to rely on IL-7Rα being internalized, is critical for triggering receptor degradation.

Proposed model for IL-7Rα trafficking. At the steady state, IL-7Rα is slowly internalized via clathrin-coated pits and recycled back to the cell surface, with a pool of receptor being degraded and replaced by newly synthesized IL-7Rα (not shown). On IL-7 stimulation, the balance is rapidly shifted toward receptor endocytosis and subsequent degradation. JAK3 activation, which appears to rely on IL-7Rα being internalized, is critical for triggering receptor degradation.

Previous work suggested that IL-7Rα is down-regulated at the T-cell surface within 30 minutes of IL-7 stimulation, possibly because of internalization.23 Alternatively, it has been proposed that IL-7 leads to IL-7Rα membrane shedding, instead of endocytosis.42 However, this has been consistently challenged by recent studies.43-45 In the present work, we describe, for the first time, the kinetics and mechanisms of IL-7Rα membrane trafficking in human T cells and confirm that IL-7 rapidly down-regulates IL-7Rα surface levels. Importantly, both flow cytometric and confocal microscopy analyses revealed that IL-7Rα surface down-regulation is mediated by clathrin-dependent internalization into early endosomes. This integrates well with previous observations that IL-7 induces phosphorylation of clathrin heavy chain in mouse T cells,30 which suggested that clathrin-coated pits could be involved in IL-7Rα endocytosis. In agreement, we found that pretreatment with sucrose-containing hypertonic media, which inhibits the formation of clathrin-coated pits,29 abrogated IL-7–induced IL-7Rα internalization.

Interestingly, we found that inhibition of clathrin-coated pits also largely prevented IL-7–mediated signaling, suggesting that IL-7Rα clathrin-dependent endocytosis is essential for optimal IL-7 signal transduction. This finding is not unprecedented. There is mounting evidence that endocytosis is frequently necessary for efficient receptor-mediated signal transduction.46 For instance, signaling complexes involving EGFR are formed on the surface of early endosomes, termed signalosomes, where EGFR has been shown to associate with most of its downstream effectors.13 Furthermore, cytokine receptors, such as IL-5R and Dome, the Drosophila ortholog to human IL-6R, have been shown to rely on internalization for optimal signal transduction.15,47 Although it remains to be determined whether IL-7–mediated signaling occurs strictly at the level of the endosome, it is tempting to speculate that the association of IL-7Rα with clathrin and consequent traffic to early endosomes may provide the optimal platform for recruitment, assembly, and/or activation of the protein complexes necessary for downstream signal transduction.

From a complementary viewpoint, the ability to transduce a signal is also dependent on the availability of the receptor at the cell surface, which reflects the balance between de novo synthesis, internalization, degradation, and recycling.48 Our data suggest that IL-7Rα constitutively internalizes and either recycles back to the surface or is degraded in a process that is relatively slow: the half-life of the receptor is approximately 24 hours in nonstimulated cells. Because the expression of IL-7Rα at the cell surface of cultured T cells is roughly constant, our observations implicate that, in steady state, de novo synthesis compensates for the pool of IL-7Rα that is slowly degraded. In the presence of IL-7, the route of IL-7Rα internalization remains clathrin-dependent. However, the kinetics is substantially accelerated, and the receptor surface expression is reduced by more than 30% within only 15 minutes of stimulation. Although recycling still occurs, there is a major shift toward degradation. Consequently, the average half-life of IL-7Rα decreases dramatically to approximately 3 hours.

IL-7–induced receptor degradation appears to be mediated by both proteasomes and lysosomes. IL-7Rα colocalization with lysosomes is up-regulated on IL-7 stimulation, and pretreatment with the lysomotropic agent NH4Cl,37 which specifically inhibits pH-dependent lysosomal degradation,34 significantly down-regulated IL-7Rα degradation. In addition, the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin completely prevented IL-7Rα degradation. Lactacystin did not affect the internalization of the receptor (data not shown), suggesting that IL-7Rα internalization is independent of ubiquitin modification, in contrast to what has been described for some surface receptors.49 There is evidence that the proteasome can play not only a direct role in proteolysis but also an indirect crucial function upstream of the lysosomal pathway, acting at the endosome level to sort proteins toward lysosome degradation.50,51 Our observations that NH4Cl and lactacystin can both inhibit IL-7Rα degradation are in agreement with the hypothesis that the proteasome acts upstream of the lysosome in IL-7–mediated IL-7Rα proteolysis. The fact that lactacystin is more effective may suggest that the proteasome is involved not only in sorting of activated receptor toward the lysosome but also directly in degradation. Alternatively, it is conceivable that NH4Cl is not completely effective in inhibiting lysosomes because it relies on a change in the pH to prevent lysosome protease activity. This could explain why we were not able to rescue IL-7Rα degradation as efficiently as by blocking an upstream step in the pathway.

Our present studies further indicate that activation of JAK3 is dispensable for IL-7–mediated receptor internalization while playing a crucial role in IL-7Rα degradation. This is in line with IL-7 signaling and, therefore, JAK3 activation being evident only on receptor endocytosis. Furthermore, because JAK3 associates with the γc, our data suggest the requirement of γc for efficient IL-7–mediated IL-7Rα degradation. Although we did not analyze the fate of γc after IL-7 stimulation, there is good evidence that IL-7Rα and γc colocalize. First, it is known that binding of IL-7Rα to γc is dependent on JAK3.52 Second, similarly to IL-7Rα, γc localizes to EEA-1–positive early endosomes and LAMP-1–positive lysosomes together with JAK3.39 Notably, JAK3 is involved not only in triggering IL-7–mediated signaling but also in rapidly shutting it down by promoting the proteolysis of IL-7Rα. This indicates that the mechanisms of IL-7–dependent down-regulation of IL-7Rα are not restricted to, and can actually precede, the inhibition of IL7RA transcription.24-26 The prevalence of these mechanisms is suggestive of the biologic importance of limiting the surface expression of IL-7Rα in T cells stimulated with IL-7 and may constitute further support to the “altruistic model.”26,41 Independently of these considerations, our data clarify how IL-7 stimulation impacts the trafficking of IL-7Rα in T cells and thus may contribute to a more complete understanding of T lymphocyte biology and of diseases in which IL-7 and its receptor are thought to play a role, such as AIDS, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or leukemia.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Miguel Abecasis for providing thymic samples.

This work was supported by Instituto de Medicina Molecular startup funds and by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (grant PTDC/SAU-OBD/104816/2008; J.T.B.). C.M.H. has an FCT-SFRH PhD fellowship.

Authorship

Contribution: C.M.H. designed research, performed all the experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; J.R. analyzed and interpreted data regarding microscopy experiments; R.J.N. and G.J.G. designed research and analyzed and interpreted data; and J.T.B. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: João T. Barata, Cancer Biology Unit, Instituto de Medicina Molecular, Lisbon University Medical School, Av Prof Egas Moniz, 1649-028 Lisboa, Portugal; e-mail: joao_barata@fm.ul.pt.