Abstract

Unresponsiveness to rituximab treatment develops in many patients prompting elucidation of underlying molecular pathways. It was recently observed that rituximab-resistant lymphoma cells exhibit up-regulation of components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). Therefore, we investigated in more detail the role of this system in the regulation of CD20 levels and the influence of proteasome inhibitors on rituximab-mediated complement-dependent cytotoxicity (R-CDC). We observed that incubation of Raji cells with rituximab leads to increased levels of ubiquitinated CD20. However, inhibition of the UPS was not associated with up-regulation of surface CD20 levels, although it significantly increased its ubiquitination. Short-term (24 hours) incubation of Raji cells with 10 or 20nM bortezomib did not change surface CD20 levels, but sensitized CD20+ lymphoma cells to R-CDC. Prolonged (48 hours) incubation with 20nM bortezomib, or incubation with 50nM bortezomib for 24 hours led to a significant decrease in surface CD20 levels as well as R-CDC. These effects were partly reversed by bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of lysosomal/autophagosomal pathway of protein degradation. These studies indicate that CD20 levels are regulated by 2 proteolytic systems and that the use of proteasome inhibitors may be associated with unexpected negative influence on R-CDC.

Introduction

Rituximab, a genetically engineered chimeric monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to CD20, represents a major therapeutic advance in the treatment of B-cell malignancies and some autoimmune diseases. Its mechanisms of antitumor action include induction of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC),1,2 complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC),1,3,4 induction of apoptosis (after cross-linking),5 and possibly facilitation of adaptive immune response.6

Combination therapies with rituximab and systemic chemotherapy result in higher response rates and prolonged survival. However, most patients experience relapses and the efficacy of rituximab seems to decrease during the treatment.7-9 The explanation for this therapeutic resistance is not completely elucidated. Possible mechanisms include down-regulation of CD20 expression,10-12 induction of complement regulatory proteins on the surface of malignant cells,13-15 formation of blocking antichimeric antibodies,16 or changes in membrane lipid composition.17,18 Therefore, novel treatment regimens in which rituximab is combined with therapeutics interfering with resistance mechanisms are needed.

The B cell–specific surface marker CD20 was considered a stable target for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). However, this concept needs to be revisited in light of recent studies indicating that CD20 expression is regulated at both pretranscriptional and posttranscriptional levels.19,20 For example, it is now widely recognized that surface CD20 is modulated by rituximab itself in a process referred to as shaving, which in vitro resembles trogocytosis and is a process of plasma membrane exchange within immunologic synapse that forms between tumor- and FcγR-bearing cell.21-23 In addition, an increasing number of therapeutics have been reported to affect the amounts of surface CD20. These include cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-4 as well as several approved or experimental therapeutics. For example, prednisolone,14 bryostatin-1,20 radiotherapy,24,25 and reactive oxygen species25 were demonstrated to up-regulate CD20 levels in B cells or B-cell tumors. On the other hand, lenalidomide26 or CD40 ligation in normal B cells27 down-regulates CD20 levels.

Little is known about the molecular mechanisms governing regulation of CD20 levels. Elucidation of these mechanisms is of potential clinical relevance as biologic effects of anti-CD20 mAb depend to a large extent on the density of surface CD20 expression,10,15 and rituximab resistance is at least to some extent associated with lowered CD20 levels.28,29 Recent studies indicate that CD20 is regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, as 5-azacytidine (which inhibits DNA methyltransferase) can increase CD20 levels in primary B-cell lymphoma cells,19 and trichostatin A (a modulator of histone-acetylation status) increases CD20 mRNA and protein levels in RRBL1, a B-cell lymphoma cell line.30 Moreover, Czuczman et al have recently demonstrated using cDNA microarrays that rituximab-resistant cells reveal decreased surface CD20 levels and exhibit up-regulation of the components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS).31 It is unclear, however, why incubation of rituximab-resistant cell lines with bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, led to increased expression of COOH-terminal region of the internal domain of CD20, but not the whole CD20 molecule.31

Here, we decided to address in more detail the influence of proteasome inhibitors on the CD20 levels as well as rituximab-mediated CDC and ADCC toward CD20+ B-cell malignancies.

Methods

Cell culture

Human Burkitt lymphoma (Daudi, Raji, Ramos) and human follicular lymphoma (DoHH2) cell lines were purchased from ATCC. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 250 ng/mL amphotericin B (Invitrogen). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a fully humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and were passaged every other day. Normal B cells from healthy volunteers or primary cells from patients with B-cell tumors (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia) were isolated from blood or bone marrow using Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich). Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Warsaw and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient signed an informed consent for the procedures.

Isolation of primary normal B cells from blood of healthy donors

The peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from blood of healthy donors using Histopaque 1077. Briefly, blood (50 mL from each donor) was diluted twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Every 10 mL of diluted blood was slowly layered on the top of 3 mL of Histopaque 1077. After 30-minute centrifugation (700g, 25°C), white blood cell rings were isolated, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in RPMI at a concentration of 108 cells/mL. Isolation of B cells was performed using purple EasySep magnet and human CD19+ selection kit (StemCell Technologies). According to the manufacturer's protocol, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were incubated for 15 minutes with positive selection cocktail followed by 10-minute incubation with magnetic nanoparticles. A total of four 5-minute separations in the magnet were performed.

Reagents

Rituximab, a chimeric immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), was purchased from Roche. Bortezomib obtained from Millennium Pharmaceuticals was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl. MG132, epoxomycin, proteasome inhibitor (PSI), and tunicamycin were purchased from Calbiochem, and were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Acridine orange (dissolved in PBS), bafilomycin A1 (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide), and 3-methyladenine (dissolved in dH2O) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Recombinant heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) was purchased from Assay Designs.

Cytotoxicity assay

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity was determined by an assay with 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) as described.17 For ADCC assay, a nonradioactive colorimetric assay based on the measurement of lactate dehydrogenase activity released from the cytosol of damaged cells was used (Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS; Roche) as described by the manufacturer.

Flow cytometry

The following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were used for flow cytometry studies: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD20 (clone B9E9 [HRC20]; Beckman Coulter), anti-CD55 (clone IA10; BD Pharmingen), anti-CD59 (clone p282; BD Pharmingen), and FITC-conjugated IgG1 (isotypic control; Beckman Coulter). The following unconjugated mAbs were used: anti-CD21 (Gen Trak), anti-CD45RA (clone L48; BD Biosciences), anti-CD46 (clone J4.48; Beckman Coulter), anti-CD54 (clone 84H10; Immunotech), anti–HLA-DR (clone L243; BD Biosciences), and anti–C5b-9 (clone aE11, mAb reacting with neoepitope on poly C9 complement factor; DakoCytomation). Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2 as described.17

Autophagy detection with acridine orange staining

Control- and bortezomib-pretreated cells (0.5 × 106) suspended in 1 mL of PBS were stained with 1 μg/mL acridine orange for 15 minutes; then the cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in 0.5 mL of PBS, and analyzed. Green (510-530 nm) and red (650 nm) fluorescence emission (FL1 vs FL3) illuminated with blue (488 nm) excitation light was measured with a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. The positive control cells were incubated without FBS for 24 hours.

Western blotting

For the analysis of protein expression, cells were cultured with drugs for the indicated times. After washing with PBS, the cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50nM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane base, 150nM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40 (NP-40), 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, and 1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) supplemented with Complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche). Protein concentration was measured using Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Equal amounts of proteins were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel, transferred onto Protran nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell BioScience), blocked with TBST (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane-buffered saline [pH 7.4] and 0.05% Tween 20), and supplemented with 5% nonfat milk and 5% FBS. The following antibodies at 1:1000 dilution were used for the overnight incubation: anti-CD20 (NCL-CD20-L26; Novocastra Laboratories), anti–microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-HSP70 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After extensive washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated for 45 minutes with peroxidase-conjugated ImmunoPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG or Goat Anti-Rabbit F(ab′)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). The chemiluminescence reaction for horseradish peroxidase was developed using the SuperSignal WestPico Trail Kit (Pierce) on a standard x-ray film. The blots were stripped in 0.1M glycine (pH 2.6) and reprobed with antitubulin mouse mAb (Calbiochem).

Immunoprecipitation

For immunoprecipitation, 4 × 106 Raji cells (control or drug treated) were lysed in 1 mL of lysis buffer (50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid–KOH, pH 7.4, at 4°C, 100mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, and 0.1% NP-40). After centrifugation (15 minutes, 16 000g at 4°C), protein concentration was determined with Bio-Rad Protein Assay and all lysates were diluted to the same concentration. Next, 1 mL of lysate from each group was precleared with agarose beads and incubated with 5 μL of anti-CD20 antibody (NCL-CD20-L26; Novocastra Laboratories) for 1 hour at 4°C on a rotary wheel, and then 50 μL of protein G bead slurry (HiTrap; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB) was added for overnight incubation at 4°C on a rotary wheel. Afterward, beads were spun at 16 000g for 30 seconds and the supernatant was collected. Then beads were resuspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer without 0.1% NP-40 and washed with it 3 times. The buffer was aspirated and 10 μL of the 5× Laemmli sample buffer and 70 μL of the 1× Laemmli sample buffer were added to the beads. Antigen and antibodies were released from protein G by boiling for 5 minutes. Subsequently, 40 μL of samples was loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and the ubiquitination of CD20 was evaluated with antiubiquitin antibody (clone P4D1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described in “Western blotting.” To detect CD20 in the culture supernatants, 2 × 106 Raji cells were incubated with bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours. The cells were centrifuged and the supernatants were collected. To 5 mL of each supernatant, 5 μL of anti-CD20 antibody (Novocastra Laboratories) was added and immunoprecipitation was performed. Detection of recombinant HSP70 added to the culture supernatants at 20-ng/mL concentration served as a positive control for immunoprecipitation procedure.

Surface protein biotinylation

Control- and bortezomib-treated cells, washed 3 times with ice-cold PBS and resuspended at a density of 25 × 106 cells/mL, were surface-labeled with 2mM (final concentration) EZ-link sulfo–N-hydroxysuccinimido (NHS)–biotin (Pierce) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed 3 times (in PBS with 100mM glycine) and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors. Next, samples containing equal amounts of total cellular proteins were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with immobilized NeutrAvidin protein (Pierce) to separate the biotinylated surface protein from nonbiotinylated cellular proteins. Next, NeutrAvidin beads were spun at 400g for 4 minutes, and the supernatant (cytosol fraction) was collected and used subsequently as a control of biotinylation process. After 5-minute boiling in deionized water to release biotinylated proteins from NeutrAvidin beads, an additional immunoprecipitation step was used to separate membrane CD20 from other membrane proteins that may also undergo ubiquitination and affect the results of subsequent Western blotting analysis. Then, 900 μL of immunoprecipitation buffer (50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid–KOH, pH 7.4, at 4°C, 100mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2) was added to 100 μL of supernatant obtained after spinning down boiled NeutrAvidin beads. The mixture was than incubated with 5 μL of anti-CD20 antibody (NCL-CD20-L26; Novocastra Laboratories) for 1 hour at 4°C on a rotary wheel, and then 50 μL of protein G bead slurry (HiTrap; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB) was added for overnight incubation at 4°C on a rotary wheel. Anti-CD20 antibody used in this experimental setting recognizes cytoplasmic domain of CD20 molecule that is not affected by biotinylation. Afterward, beads were spun at 16 000g for 30 seconds and the supernatant was collected and used as a biotinylation and CD20 precipitation control (membrane fraction). After 5 washings, gel-bound complexes were boiled in 2× Laemmli sample buffer that releases immunoprecipitated proteins from their binding with antibodies and protein G agarose beads and subsequently analyzed for CD20 ubiquitination with Western blotting using anti-CD20 mAb (Novocastra Laboratories) and antiubiquitin antibody. Anti–intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and antitubulin antibodies (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for detection of membrane and cytosolic proteins, respectively, in subcellular fractions.

RT-PCR

RNA was isolated using Chomczynski modified method. Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. PCR was performed using GoTaq Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega) using pairs of primers indicated in Table 1. Amplification products were analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Statistical analysis

Data were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2007. Differences in in vitro cytotoxicity assays were analyzed for significance by Student t test. Significance was defined as a 2-sided P value less than .05. All the experiments using cell lines were performed independently at least 3 times.

Results

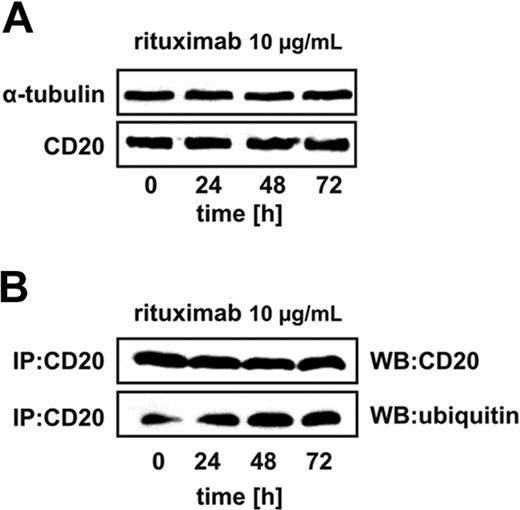

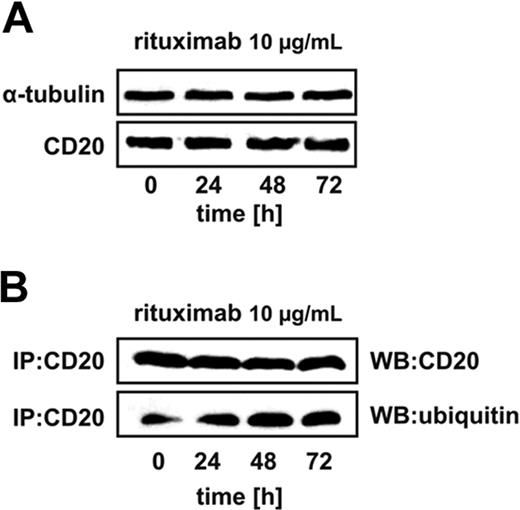

Rituximab binding increases the levels of ubiquitinated CD20

It was recently demonstrated that incubation of CD20+ B-cell tumors with rituximab leads to decreased surface levels of CD20 accompanied by induction of several components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system.31 Therefore, Raji cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL rituximab for 24 to 72 hours to determine whether it affects the levels and/or ubiquitination of CD20. Western blotting analysis was used to determine the total cellular levels of CD20 as the detection of surface CD20 with B9E9 antibodies used in flow cytometry is hampered by rituximab (data not shown). The levels of CD20 did not change in rituximab-incubated cells as detected by Western blotting (Figure 1A). However, immunoprecipitation of CD20 followed by immunoblotting revealed that it is already ubiquitinated in control cells and this posttranslational modification of CD20 becomes further increased in rituximab-treated cells (Figure 1B). This observation fosters the possibility that the CD20 levels can be regulated by proteasomes.

Rituximab binding increases CD20 ubiquitination. (A) Raji cells were seeded into the 25-cm2 bottles at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/10 mL and exposed to 10 μg/mL rituximab for 24, 48, or 72 hours, after which protein lysates were prepared and analyzed in Western blotting. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of total protein. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antitubulin and anti-CD20 antibodies. (B) Raji cells were seeded into the 25-cm2 bottles at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to 10 μg/mL rituximab for 24, 48, or 72 hours, after which protein lysates were prepared. CD20 antigen was immunoprecipitated from samples with protein G bead slurry and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies.

Rituximab binding increases CD20 ubiquitination. (A) Raji cells were seeded into the 25-cm2 bottles at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/10 mL and exposed to 10 μg/mL rituximab for 24, 48, or 72 hours, after which protein lysates were prepared and analyzed in Western blotting. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of total protein. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antitubulin and anti-CD20 antibodies. (B) Raji cells were seeded into the 25-cm2 bottles at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to 10 μg/mL rituximab for 24, 48, or 72 hours, after which protein lysates were prepared. CD20 antigen was immunoprecipitated from samples with protein G bead slurry and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies.

Bortezomib modulates surface CD20 levels

In preliminary experiments, the cytostatic/cytotoxic effects of bortezomib as well as other proteasome inhibitors were investigated to establish concentrations of these compounds that would not exert excessive toxicity against tumor cells and elicit nonspecific effects in dying tumor cells (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). To further limit any direct influence of proteasome inhibitors on the survival of tumor cells in flow cytometry and CDC assays, all experiments were done with equal numbers of targets preincubated with bortezomib and then rinsed and cocultured with rituximab and 10% human AB serum for 1 hour.

To determine the influence of proteasome inhibition on the surface CD20 levels, Raji cells were incubated with bortezomib for 12, 24, and 72 hours. Bortezomib was used at low concentrations (10 and 20nM) that do not affect the viability of tumor cells and at a higher concentration (50nM) that decreases viability of Raji cells by approximately 20%. Bortezomib at 10- and 20-nM concentrations did not affect the CD20 levels for the first 24 hours of incubation when measured in flow cytometry (Figure 2A). However, when used at a higher (50nM) concentration or for prolonged incubation time (48 hours) with 10- and 20-nM concentrations bortezomib significantly decreased the surface CD20 levels. Bortezomib-mediated modulation of surface CD20 expression was also observed in other CD20+ lymphoma cell lines: Daudi (supplemental Figure 2), DoHH2 (supplemental Figure 3), and Ramos (supplemental Figure 4). Western blotting analysis of whole Raji cells lysates revealed that 20nM bortezomib used for 12 hours increases CD20 levels by approximately 50%. However, a 48-hour incubation with 20nM or a 24-hour incubation with 50nM bortezomib led to a significant drop in CD20 levels (Figure 2B). RT-PCR indicated only a slight decrease in CD20 mRNA levels after incubation of Raji cells with 20nM bortezomib detected only after 48 hours (Figure 2C).

The influence of bortezomib on the expression of CD20 in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Then, cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. (B) CD20 protein levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or 20 and 50nM bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with Western blotting (NCL-CD20-L26 mAb). (C) CD20 mRNA levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or 20 and 50nM bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with RT-PCR. (D) Raji cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours and stained for CD20, CD21, CD45RA, CD54, or HLA-DR. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) serves as a measure for mAb binding on a per-cell basis. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Primary CD20+ tumor cells (chronic lymphocytic leukemia: patient 1 [Pt1], diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Pt2, and mantle cell lymphoma: Pt3) were incubated with either 1 or 10 nM bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours. Then, cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. *P < .05 (Student t test). (F) Immunoprecipitation of Raji cell culture supernatants with anti-CD20 mAb (NCL-CD20-L26). Positive controls included a lane with CD20 immunoprecipitated from Raji lysates (L) and soluble recombinant HSP70 added at 20-ng/mL concentration to the cultured cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-HSP70 mAb (Sup). Lane designated rHSP70 refers to 20 ng of electrophoresed recombinant HSP70.

The influence of bortezomib on the expression of CD20 in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Then, cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. (B) CD20 protein levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or 20 and 50nM bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with Western blotting (NCL-CD20-L26 mAb). (C) CD20 mRNA levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or 20 and 50nM bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with RT-PCR. (D) Raji cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours and stained for CD20, CD21, CD45RA, CD54, or HLA-DR. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) serves as a measure for mAb binding on a per-cell basis. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Primary CD20+ tumor cells (chronic lymphocytic leukemia: patient 1 [Pt1], diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Pt2, and mantle cell lymphoma: Pt3) were incubated with either 1 or 10 nM bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours. Then, cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. *P < .05 (Student t test). (F) Immunoprecipitation of Raji cell culture supernatants with anti-CD20 mAb (NCL-CD20-L26). Positive controls included a lane with CD20 immunoprecipitated from Raji lysates (L) and soluble recombinant HSP70 added at 20-ng/mL concentration to the cultured cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-HSP70 mAb (Sup). Lane designated rHSP70 refers to 20 ng of electrophoresed recombinant HSP70.

Incubation of Raji cells with bortezomib did not significantly affect surface levels of other B-cell surface molecules such as CD21, CD45RA, CD54, or HLA-DR (Figure 2D and supplemental Figure 5).

Bortezomib-mediated modulation of CD20 levels was also observed in 3 consecutive primary tumor cultures obtained from patients with CD20+ tumors. In 2 of these there was an up-regulation of CD20 after 24 hours of incubation with bortezomib and down-regulation at 48 hours. In the third patient's cells, there was no significant change in CD20 levels at 24 hours, but a significant drop at 48 hours (Figure 2E).

To determine whether incubation of Raji cells with bortezomib may lead to extracellular release of CD20 to the culture supernatant, an immunoprecipitation assay was done with anti-CD20 mAb. These experiments revealed that there is no soluble CD20 in controls or in groups incubated with bortezomib (Figure 2F).

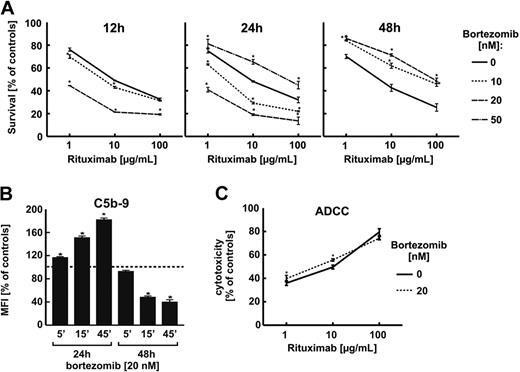

Bortezomib and other proteasome inhibitors affect rituximab-mediated CDC but not ADCC

To investigate whether changes in CD20 levels correlate with rituximab-mediated CDC (R-CDC), Raji cells were preincubated with proteasome inhibitor, collected, rinsed with PBS, and exposed to rituximab (1, 10, and 100 μg/mL) in the presence of 10% human AB serum for 1 hour. Incubation of Raji cells with bortezomib at 10- and 20-nM concentrations for 12 and 24 hours significantly potentiated R-CDC, but a 24-hour incubation with 50nM or prolonged (48 hours) incubation with 10- or 20-nM bortezomib concentrations significantly decreased R-CDC (Figure 3A). Bortezomib-mediated modulation of R-CDC was also observed when 50% serum was used for 1, 4, or 24 hours (supplemental Figure 6). Changes in sensitivity to R-CDC in bortezomib-treated cells correlated with deposition in the plasmalemma of membrane attack complex (C5b-9)—a 24-hour incubation with proteasome inhibitor was associated with increased deposition of C5b-9, whereas a prolonged (48 hours) incubation led to decreased deposition of C5b-9 (Figure 3B). Incubation of Raji cells with bortezomib did not affect the sensitivity of tumor cells to ADCC (Figure 3C).

Bortezomib enhances R-CDC but not R-ADCC in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at 10-, 20-, or 50-nM concentration for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. (B) Control- and bortezomib-pretreated Raji cells were suspended in the medium (2 × 106 in 2 mL) with 10 μg/mL rituximab and 10% human AB serum as a source of the complement and incubated for 5, 15, and 45 minutes. Then, they were washed twice with PBS and incubated with anti–C5b-9 antibody as described in “Flow cytometry.” (C) Raji cells were seeded into a 96-well flat-bottom plate (5 × 104 cells/well). Then, rituximab (1, 10, or 100 μg/mL) or a control medium was added for 15 minutes followed by addition of peripheral blood mononuclear cells used as effector cells at an effector-to-target (E/T) cell ratio of 100:1. After incubation (6 hours, 37°C), assay was developed using Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS. *P < .05 (Student t test).

Bortezomib enhances R-CDC but not R-ADCC in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at 10-, 20-, or 50-nM concentration for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. (B) Control- and bortezomib-pretreated Raji cells were suspended in the medium (2 × 106 in 2 mL) with 10 μg/mL rituximab and 10% human AB serum as a source of the complement and incubated for 5, 15, and 45 minutes. Then, they were washed twice with PBS and incubated with anti–C5b-9 antibody as described in “Flow cytometry.” (C) Raji cells were seeded into a 96-well flat-bottom plate (5 × 104 cells/well). Then, rituximab (1, 10, or 100 μg/mL) or a control medium was added for 15 minutes followed by addition of peripheral blood mononuclear cells used as effector cells at an effector-to-target (E/T) cell ratio of 100:1. After incubation (6 hours, 37°C), assay was developed using Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS. *P < .05 (Student t test).

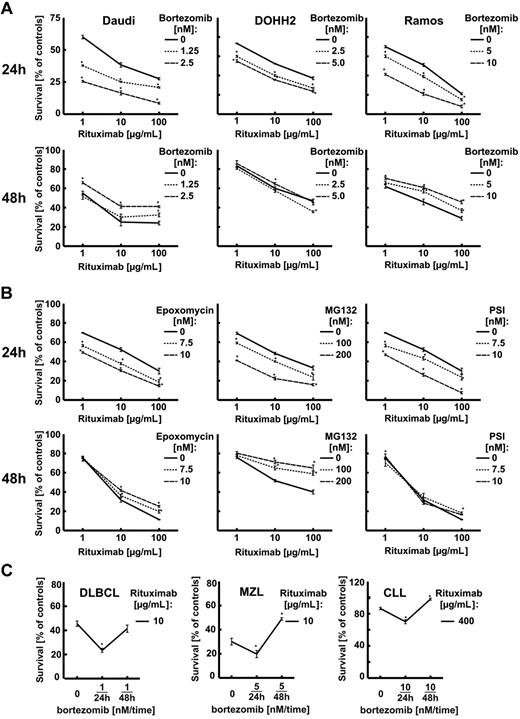

Similar changes in R-CDC sensitivity were observed in other CD20+ B-cell tumors (Daudi, DoHH2, Ramos)—a short incubation time (24 hours) was associated with increased sensitivity, whereas a longer incubation time (48 hours) resulted in decreased R-CDC (Figure 4A). In addition, other proteasome inhibitors (epoxomycin, MG132, and PSI) sensitized Raji cells to R-CDC when used for a 24-hour incubation time, and impaired R-CDC when used for 48 hours (Figure 4B).

Proteasome inhibitors enhance R-CDC. (A) Daudi, DoHH2, and Ramos cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. (B) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent, epoxomycin, MG-132, or PSI at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or proteasome inhibitor–pretreated cells without rituximab. (C) Freshly isolated cells from patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. *P < .05 (Student t test).

Proteasome inhibitors enhance R-CDC. (A) Daudi, DoHH2, and Ramos cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. (B) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent, epoxomycin, MG-132, or PSI at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or proteasome inhibitor–pretreated cells without rituximab. (C) Freshly isolated cells from patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. *P < .05 (Student t test).

A 24-hour preincubation with bortezomib increased whereas a 48-hour preincubation decreased R-CDC in 3 primary cell cultures of CD20+ B-cell tumors freshly obtained from patients (Figure 4C). Bortezomib was used at low (1, 5, or 10nM) concentrations in these experiments that were not associated with significant cytostatic/cytotoxic effects (not shown).

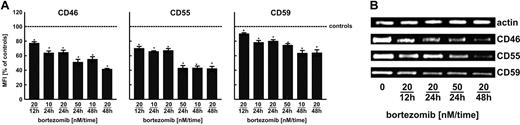

Bortezomib regulates complement regulatory protein levels

An intriguing observation that short-term (up to 24 hours) preincubation of Raji cells with bortezomib or other proteasome inhibitors sensitizes these cells to R-CDC without accompanying rise in CD20 levels indicates that other mechanisms may contribute to this effect. One potential mechanism may result from modulation of surface complement regulatory proteins levels. Indeed, flow cytometry (Figure 5A) revealed that bortezomib strongly affects surface levels of CD46, CD55, and CD59. This effect likely results from transcriptional regulation, as RT-PCR analyses revealed a drop in mRNA levels for all 3 complement regulatory proteins (Figure 5B).

Bortezomib decreases the expression of complement inhibitors (CD46, CD55, CD59) at the transcriptional level in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Then, cells at a density of 105/100 μL were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD55 and CD59 or with unconjugated mAb against CD46 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark. Then, cells incubated with anti-CD46 were washed twice with PBS and incubated with PE-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG for another 30 minutes on ice in the dark. Subsequently, cells were washed twice with PBS and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) serves as a measure for mAb binding on a per-cell basis. *P < .05 (Student t test). (B) CD46, CD55, and CD59 mRNA levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with RT-PCR.

Bortezomib decreases the expression of complement inhibitors (CD46, CD55, CD59) at the transcriptional level in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Then, cells at a density of 105/100 μL were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD55 and CD59 or with unconjugated mAb against CD46 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark. Then, cells incubated with anti-CD46 were washed twice with PBS and incubated with PE-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG for another 30 minutes on ice in the dark. Subsequently, cells were washed twice with PBS and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) serves as a measure for mAb binding on a per-cell basis. *P < .05 (Student t test). (B) CD46, CD55, and CD59 mRNA levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with RT-PCR.

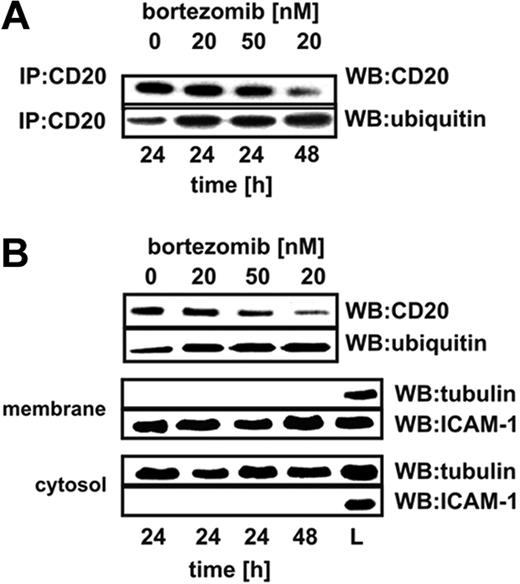

Bortezomib increases ubiquitination of surface CD20 molecules

To investigate the influence of proteasome inhibition on the levels as well as ubiquitination of CD20, controls or cells incubated with bortezomib were lysed and CD20 was immunoprecipitated. Immunoprecipitation of CD20 followed by Western blotting analysis revealed that a 24-hour incubation of Raji cells with a high (50nM) bortezomib concentration or for prolonged time (48 hours) with 20nM bortezomib led to decreased levels of CD20 in total cellular lysates (Figure 6A top). Decreased levels of CD20 in Raji cells incubated with a high (50nM) bortezomib concentration or for prolonged time (48 hours) with a lower (20nM) bortezomib concentration were accompanied by strongly increased levels of its ubiquitination (Figure 6A bottom). Immunoprecipitation provides information on the whole pool of CD20 including intracellular and plasma membrane–associated molecules. To check whether changes in ubiquitination include membrane CD20 molecules, surface proteins were precipitated with EZ-link sulfo-NHS-biotin. This water-soluble and membrane-impermeable reagent stably binds to primary amino (-NH2) groups of extracellular portions of membrane proteins. Labeled cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were precipitated with immobilized NeutrAvidin protein. After detachment of NeutrAvidin from the mixture of precipitated surface proteins, an additional immunoprecipitation step with anti-CD20 mAb was performed. Electrophoresis of the immunoprecipitates followed by immunoblotting with anti-CD20 mAb revealed that bortezomib decreases CD20 levels in the plasma membrane and that membrane CD20 is ubiquitinated (Figure 6B top). Western blotting of the EZ-link sulfo-NHS-biotin–precipitated material confirmed that it contains membrane (ICAM-1) but not cytosolic (tubulin) proteins (Figure 6B middle). The fraction of the lysate that was not precipitated contained cytosolic but not membrane proteins (Figure 6B bottom). Preliminary experiments revealed that incubation of normal B cells (isolated from peripheral blood of 5 consecutive healthy volunteers with anti-CD19 magnetic beads) with bortezomib at 1- and 10-nM concentration for 24 and 48 hours leads to increased CD20 ubiquitination. In contrast to tumor cells, the levels of CD20 in normal B cells were up-regulated (supplemental Figure 7).

Proteasome inhibition increases ubiquitination of CD20. (A) Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours, after which protein lysates were prepared. CD20 antigen was immunoprecipitated from samples with protein G bead slurry and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies. IP indicates immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blotting. (B) To assess the ubiquitination of membrane CD20, Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, extracellular portions of membrane proteins were bound with EZ-link sulfo-NHS-biotin. Labeled cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were precipitated with immobilized NeutrAvidin protein. Subsequently, from the mixture of boiled precipitated surface proteins, an additional immunoprecipitation step with anti-CD20 mAb (NCL-CD20-L26) was performed. Immunoprecipitates underwent electrophoresis followed by blotting with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies. ICAM-1 is a marker for membrane fraction; and tubulin, for a cytosolic fraction. L indicates the total cell lysate that served as a positive control; WB, Western blotting.

Proteasome inhibition increases ubiquitination of CD20. (A) Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours, after which protein lysates were prepared. CD20 antigen was immunoprecipitated from samples with protein G bead slurry and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies. IP indicates immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blotting. (B) To assess the ubiquitination of membrane CD20, Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, extracellular portions of membrane proteins were bound with EZ-link sulfo-NHS-biotin. Labeled cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were precipitated with immobilized NeutrAvidin protein. Subsequently, from the mixture of boiled precipitated surface proteins, an additional immunoprecipitation step with anti-CD20 mAb (NCL-CD20-L26) was performed. Immunoprecipitates underwent electrophoresis followed by blotting with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies. ICAM-1 is a marker for membrane fraction; and tubulin, for a cytosolic fraction. L indicates the total cell lysate that served as a positive control; WB, Western blotting.

Bortezomib induces lysosomal/autophagic degradation of CD20

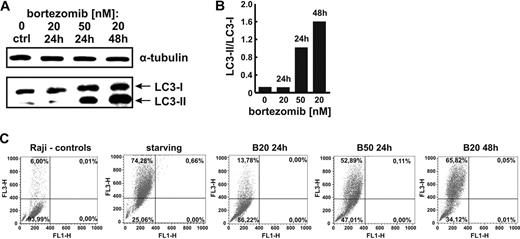

The unexpected finding of decreased levels of CD20 and increased levels of its ubiquitination in cells incubated with bortezomib indicates that inhibition of proteasome activity may lead to secondary activation of another proteolytic system that participates in the degradation of CD20. Previous studies indicate that there may be an extensive cross-talk between ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagic pathway of protein degradation.32 Indeed, we have observed that incubation of Raji cells with bortezomib leads to processing of LC3-I to its phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form, LC3-II, which participates in the autophagic sequestration process (Figure 7A-B), and to increased staining with acridine orange, an lysosomal/autophagosomal marker (Figures 7C and 8A), indicating induction of autophagy (see also supplemental Figure 8).

Proteasome inhibition with bortezomib activates autophagy in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, total cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed using anti-LC3B antibody against LC3B-I and LC3B-II fragments. (B) Densitometric analysis of LC3B-II to LC3B-I ratio using the Quantity One 4.6.6 software. (C) Raji cells were incubated with indicated concentrations of bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours. Then, cells were stained with 1 μg/mL acridine orange for 15 minutes, washed with PBS, and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2 (Bio-Rad).

Proteasome inhibition with bortezomib activates autophagy in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours. Then, total cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed using anti-LC3B antibody against LC3B-I and LC3B-II fragments. (B) Densitometric analysis of LC3B-II to LC3B-I ratio using the Quantity One 4.6.6 software. (C) Raji cells were incubated with indicated concentrations of bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours. Then, cells were stained with 1 μg/mL acridine orange for 15 minutes, washed with PBS, and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2 (Bio-Rad).

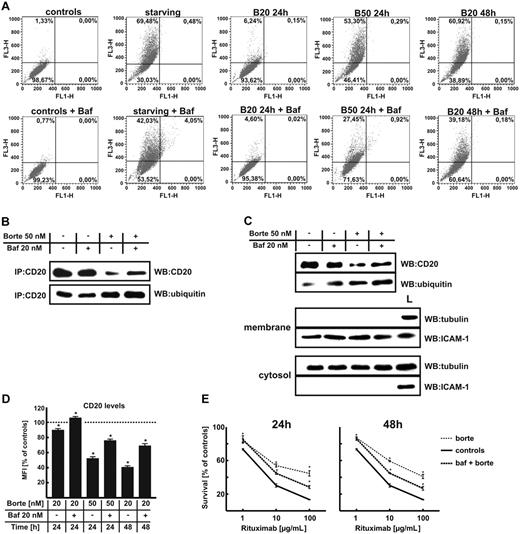

Simultaneous inhibition of the proteasome activity and autophagy increases the CD20 levels in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with indicated concentrations of bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf). Then, cells were stained with 1 μg/mL acridine orange for 15 minutes, washed with PBS, and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. (B) Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. CD20 was immunoprecipitated from samples with protein G bead slurry and analyzed with Western blotting. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies. IP indicates immunoprecipitation; and WB, Western blotting. (C) Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were incubated with bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. Then, cells were incubated with EZ-link sulfo-NHS-biotin. Labeled cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were precipitated with immobilized NeutrAvidin protein. Subsequently, from the mixture of boiled precipitated surface proteins an additional immunoprecipitation step with anti-CD20 mAb (NCL-CD20-L26) was performed. Immunoprecipitates underwent electrophoresis followed by blotting with antiubiquitin, anti-CD20, antitubulin, or anti–ICAM-1 antibodies. L indicates the total cell lysate, positive control; and WB, Western blotting. (D) Raji cells were incubated with bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. Then, cells at a density of 105/100 μL were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at 50-nM concentration for 24 hours or at 20-nM concentration for 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. *P < .05 (Student t test).

Simultaneous inhibition of the proteasome activity and autophagy increases the CD20 levels in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with indicated concentrations of bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf). Then, cells were stained with 1 μg/mL acridine orange for 15 minutes, washed with PBS, and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. (B) Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were exposed to bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. CD20 was immunoprecipitated from samples with protein G bead slurry and analyzed with Western blotting. Blots were sequentially probed (after stripping) with antiubiquitin and anti-CD20 antibodies. IP indicates immunoprecipitation; and WB, Western blotting. (C) Raji cells were seeded into the flask bottles at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/10 mL. The cells were incubated with bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. Then, cells were incubated with EZ-link sulfo-NHS-biotin. Labeled cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were precipitated with immobilized NeutrAvidin protein. Subsequently, from the mixture of boiled precipitated surface proteins an additional immunoprecipitation step with anti-CD20 mAb (NCL-CD20-L26) was performed. Immunoprecipitates underwent electrophoresis followed by blotting with antiubiquitin, anti-CD20, antitubulin, or anti–ICAM-1 antibodies. L indicates the total cell lysate, positive control; and WB, Western blotting. (D) Raji cells were incubated with bortezomib at indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. Then, cells at a density of 105/100 μL were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib at 50-nM concentration for 24 hours or at 20-nM concentration for 48 hours with or without 20nM bafilomycin A1. Then, equal numbers of cells (105/well) were incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions (from 1 to 100 μg/mL) of rituximab in the presence of 10% human AB serum as a complement source. Cell viability was measured with an MTT assay. The survival of cells is presented as percentage of corresponding diluent- or bortezomib-pretreated cells without rituximab. *P < .05 (Student t test).

Bafilomycin A1, a vacuolar type H(+)–ATPase inhibitor, suppresses autophagy by preventing acidification of lysosomes and their fusion with autophagosomes.33 Incubation of Raji cells with 20nM bafilomycin A1 decreased the percentage of bortezomib-treated autophagic cells (Figure 8A). To determine whether inhibition of lysosomal degradation/autophagy in bortezomib-treated cells would have any impact on CD20 levels, Raji cells were incubated with proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib at 50nM for 24 hours) and/or 20nM bafilomycin A1. Immunoprecipitation of CD20 followed by Western blotting analysis revealed that bafilomycin A1 partly restored CD20 levels in whole Raji cells lysates (Figure 8B) as well as in the membrane fraction (Figure 8C). In addition, flow cytometry analyses revealed that both bafilomycin A1 (Figure 8D) and 3-methyladenine (supplemental Figure 7) reverse bortezomib-induced decrease in surface CD20 levels. Partial restoration of surface CD20 expression with bafilomycin A1 correlated with partial restoration of R-CDC in bortezomib-treated Raji cells (Figure 8E).

Discussion

The results presented in this article report for the first time that CD20 is ubiquitinated in tumor cells and that rituximab binding increases ubiquitination of this molecule (Figure 1B). The significance of this process remains to be elucidated. Numerous integral membrane proteins, including receptors, channels, transporters, and enzymes, undergo posttranslational modification by the covalent attachment of ubiquitin. This process leads to targeting of the modified proteins for proteasomal degradation or serves as a molecular recognition signal in membrane trafficking or regulation of endocytosis.34 Circumstantial evidence indicates that ubiquitination may also be involved in targeting of membrane proteins for degradation in lysosomes.35 Despite increased ubiquitination, we have not observed modulation of CD20 levels by rituximab (Figure 1A). However, inhibition of proteasome activity resulted in bimodal regulation of CD20 levels. Bortezomib used at 10 or 20nM for up to 24 hours did not affect surface CD20 levels (Figure 2A,D), but increased the amount of CD20 in total cellular lysates (Figure 2B). This observation indicates that the cellular pool of CD20 is to some extent regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Incubation of Raji cells with 50nM bortezomib for 24 hours or with 20nM bortezomib for 48 hours resulted in an unexpected drop in surface CD20 levels (Figure 2A,D). Pandey et al have shown that there is a cross-talk between the ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy pathways.32 Up-regulation of autophagy appears to be a rescue mechanism that reduces toxicity induced by proteasome inhibition by facilitating the clearance of proteins that would otherwise accumulate in cells with impaired proteasome activity. Indeed, induction of autophagy in Raji cells incubated with bortezomib was observed (Figure 7). Concomitant inhibition of proteasome activity and vacuolar type H(+)–ATPase, which participates in acidification of lysosomes, led to a partial restoration of CD20 levels. These observations indicate that both ubiquitin-proteasome as well as lysosomal/autophagosomal pathways participate in the degradation of CD20.

Although in normal B cells bortezomib also modulated CD20 ubiquitination levels, there was an increase rather than decrease in CD20 levels at 48 hours (supplemental Figure 7). These observations indicate that the consequences of CD20 ubiquitination may be different in normal compared with transformed cells. Elucidation of the mechanisms and potential significance of these disparate outcomes requires further studies.

Changes in surface CD20 levels induced by proteasome inhibitors roughly correlated with the ability to trigger R-CDC but not ADCC. These observations are to some extent at odds with those obtained by Czuczman et al, who were the first to study R-CDC in combination with bortezomib—despite increased CD20 levels in bortezomib-treated cells, there was no influence of the proteasome inhibitor on R-CDC.31 The cells used in this study were rituximab-resistant derivatives of Raji cells obtained by a repeated incubation with rituximab. It is possible that such “rituximab-adapted” cells exhibit several additional changes that may be responsible for the discordant observations. Moreover, the 100-nM concentrations of bortezomib used by Czuczman et al were associated with significant 60% cytotoxicity (compared with controls), which may additionally affect R-CDC.

A correlation between CD20 levels and R-CDC observed in our studies is concordant with previous reports.4,15,36 For example, van Meerten et al showed a sigmoidal correlation between CD20 levels and rituximab-mediated killing via CDC, but not ADCC, in a panel of transfected clonally related lymphoid cells exhibiting a wide spectrum of CD20 expression levels.36 However, not all studies confirm a strict correlation between CD20 levels and R-CDC, indicating that also other biologic characteristics of B-cell tumors affect rituximab susceptibility.15,37 These may include expression of complement regulatory proteins.7,13,37 We observed that bortezomib modulates expression of CD46, CD55, and CD59. An initial decrease in the expression of these proteins in cells incubated with 20nM bortezomib for up to 24 hours potentiates R-CDC. However, a decrease in complement regulatory proteins is insufficient to retain R-CDC activity when accompanied by down-regulated CD20 levels in cells preincubated for 24 hours with 50nM bortezomib or with 20-nM bortezomib concentrations for 48 hours. The mechanism(s) of bortezomib-mediated changes in the levels of complement regulatory proteins were not investigated and remain to be elucidated.

The concentrations of bortezomib that were used in this study (1-50nM) are within the range of concentrations observed in patients' plasma. A maximum bortezomib concentration measured soon after its administration is within 100 to 200nM, whereas 48 hours after administration its concentration drops to 10 to 20nM.38,39

Despite convincing effectiveness, the antitumor potency of rituximab used alone or in combination with chemotherapy is frequently unsatisfactory. A significant percentage of rituximab-treated patients experience relapse and tumor progression. Recent studies have indicated that the combination of bortezomib and rituximab promotes apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma cells after rituximab cross-linking with secondary goat anti–human IgG antibodies.40 Bortezomib also potentiated growth-inhibitory effects of the combination of rituximab and cyclophosphamide in mantle cell lymphoma cells,41 but the effectiveness of the combination of rituximab and bortezomib without additional chemotherapeutics was not studied. The results of recent clinical trials revealed that bortezomib can potentiate antitumor effects of the R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) combination in patients with B-cell lymphomas,42 and that the triple combination of bortezomib, dexamethasone, and rituximab appears to be superior to other rituximab-based regimens in the treatment of Waldenström macroglobulinemia.43 However, in all clinical studies, bortezomib was used together with rituximab and other therapeutics making it impossible to discern which components of the combination treatment were responsible for the observed antitumor effects. The occurrence of reversible peripheral neuropathy led to premature discontinuation of bortezomib administration in the majority of the treated patients and prompt for exploration of alternative schedules for bortezomib administration. Our observations indicate that the timing as well as doses of bortezomib may significantly affect rituximab-mediated activation of the complement cascade, which significantly contributes to antitumor effects of rituximab. Results of clinical trials should provide further information on the interaction between bortezomib and rituximab, especially considering that it is still unresolved whether CDC or ADCC is more important in the antitumor effects of rituximab.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Czerepinska and Elzbieta Gutowska for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants 1M19/N and 1M19/WB1/07 from the Medical University of Warsaw, N401 3240 33 from Polish Ministry of Science, and the European Union within European Regional Development Fund through Innovative Economy grant POIG.01.01.02-00-008/08. None of these organizations had any influence on either the course of the studies or the preparation of the paper. J.G. and J.B. are recipients of the Mistrz Award from the Foundation for Polish Science. M.W. is a recipient of the START Award from the Foundation for Polish Science. J.G, M.W., and K.B. are members of TEAM Program cofinanced by the Foundation for Polish Science and the EU European Regional Development Fund.

Authorship

Contribution: J.B. performed most of the research and contributed to writing the paper; J.G. designed and performed research and wrote the paper; M.W., D.N., and K.B. performed research and contributed to writing the paper; and A.D.-I., G.W.B., K.S., and M.J. also contributed to some of the experiments and helped to edit the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jakub Golab, Department of Immunology, Center of Biostructure Research, Medical University of Warsaw, 1a Banacha Str, F Bldg, 02-097 Warsaw, Poland; e-mail: jakub.golab@wum.edu.pl.

![Figure 2. The influence of bortezomib on the expression of CD20 in Raji cells. (A) Raji cells were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Then, cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. (B) CD20 protein levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or 20 and 50nM bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with Western blotting (NCL-CD20-L26 mAb). (C) CD20 mRNA levels in Raji cells incubated with either diluent or 20 and 50nM bortezomib for 12, 24, or 48 hours were assayed with RT-PCR. (D) Raji cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with either diluent or bortezomib (10-50nM) for 12, 24, or 48 hours and stained for CD20, CD21, CD45RA, CD54, or HLA-DR. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) serves as a measure for mAb binding on a per-cell basis. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Primary CD20+ tumor cells (chronic lymphocytic leukemia: patient 1 [Pt1], diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Pt2, and mantle cell lymphoma: Pt3) were incubated with either 1 or 10 nM bortezomib for 24 or 48 hours. Then, cells (105/100 μL) were incubated with saturating amounts of FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 for 30 minutes on ice in the dark and analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro Software Version 5.2. *P < .05 (Student t test). (F) Immunoprecipitation of Raji cell culture supernatants with anti-CD20 mAb (NCL-CD20-L26). Positive controls included a lane with CD20 immunoprecipitated from Raji lysates (L) and soluble recombinant HSP70 added at 20-ng/mL concentration to the cultured cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-HSP70 mAb (Sup). Lane designated rHSP70 refers to 20 ng of electrophoresed recombinant HSP70.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/115/18/10.1182_blood-2009-09-244129/4/m_zh89991052050002.jpeg?Expires=1769609241&Signature=Kc1~qbT9kijsGLgwJGTVviEx-NBqYUAChFN5AjALNpJj0bG2Yjf5JNXta1USZtykKIoKZ59AvEJIULHpdz-y6kgmGO6muYxx4Qk4Q22dTfSkXQsAwyfY2R0uUNafi-HmiL~5boWQkwrLuaaX3pPmGR3xOpag5xieP6p5xxM3cSt4NSSQtNmMvuRtjOLbCkP~qUZpqyHJ6XFqMQq9VDdiEHnZ3DTcEu-EJ2eCSPNyU2SYA9Gjv8p3o8HUAQFM59fvmyRgMfUkUgDwSfWT7Gs7HVeEheKaWbvks8~xRmcFgjIrcbh-b-upxL52NcFGSHH1qp5Zmu9gT0jvt74RkNlPQw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)