Abstract

Blood of both humans and mice contains 2 main monocyte subsets. Here, we investigated the extent of their similarity using a microarray approach. Approximately 270 genes in humans and 550 genes in mice were differentially expressed between subsets by 2-fold or more. More than 130 of these gene expression differences were conserved between mouse and human monocyte subsets. We confirmed numerous of these differences at the cell surface protein level. Despite overall conservation, some molecules were conversely expressed between the 2 species' subsets, including CD36, CD9, and TREM-1. Other differences included a prominent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) signature in mouse monocytes, which is absent in humans, and strikingly opposed patterns of receptors involved in uptake of apoptotic cells and other phagocytic cargo between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Thus, whereas human and mouse monocyte subsets are far more broadly conserved than currently recognized, important differences between the species deserve consideration when models of human disease are studied in mice.

Introduction

Subpopulations of blood monocytes exist in humans, mice, and other species.1-4 CD14++CD16− and CD14+CD16+ cell surface protein signatures2 identify and distinguish the 2 major human monocyte subsets. In wild-type mice, monocytes can be identified as CD115+(c-fms/macrophage colony-stimulating factor [M-CSF] receptor), CD11b+, F4/80int blood cells, with monocyte subsets distinguished as Ly-6C+ and Ly-6Clo cells.4-7 Ly-6C is frequently identified by flow cytometry using the Gr-1 antibody, which recognizes an epitope of both Ly-6C and Ly-6G.8 It should be noted that monocytes express only Ly-6C.4,9 It has been proposed that CD14++CD16− human monocytes (here called CD16− monocytes), which comprise approximately 95% of human blood monocytes, are counterparts to CD115+Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes (here called Ly-6C+ monocytes), which comprise approximately 50% of circulating mouse monocytes.2,3,6,7,10 Moreover, CD14+CD16+ human monocytes (here called CD16+ monocytes) and CD115+Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes (here called Ly-6Clo monocytes) appear to bear similarity.2,3,6,7,10 These proposed similarities arise from evidence that differential expression patterns of certain molecules between the 2 major subsets are shared in humans and mice. Namely, chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR2 are more highly expressed on CD16− human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes at the mRNA or protein level,3,11,12 whereas CX3CR1 is elevated on CD16+ human and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes.3 In addition, CD11a (αL integrin; Itgal), CD62L, and CD43 are conserved in their differential expression between monocyte subsets in humans and mice.2-4,10,13 Further, CD16, the signature marker for distinguishing human monocyte subsets, was recently observed on the surface of mouse Ly-6Clo, but not Ly-6C+, monocytes.14 CD11c (αx integrin; Itgax) is more highly expressed on CD16+ human monocytes relative to CD16− human monocytes,15 and, in analogy, several groups have observed higher expression of CD11c on Ly-6Clo mouse blood monocytes (Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes appear negative).4,12,16,17 However, other studies have failed to detect CD11c on mouse monocytes at all,3,18 leaving its status as a differentially expressed molecule that is conserved between species unclear. Overall, the proposed close similarity between human and mouse monocytes is based entirely on the 8 just-mentioned molecules, as well as on parallel differences in cell diameter.3 Whether the similarity between mouse and human monocytes goes deeper than these few markers is unknown. Indeed, a recent review by Serbina et al pointed out that the overall similarity between humans and mice requires further investigation and that several critical markers should be evaluated in more detail, including CD14, CD115, Fcγ receptors in general, and other chemokine receptors.19

The individual biologic functions of the respective monocyte subsets in vivo are not completely understood, but the 2 subsets may play different roles during homeostasis and inflammation.2,18,20,21 Studies suggest that Ly-6C+ monocytes initiate inflammatory activities, whereas Ly-6Clo monocytes promotehealing and angiogenesis.20,22 In addition, Ly-6Clo monocytes exhibit patrolling behavior along the vessel wall.18 However, Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes tend to accumulate at sites of inflammation far less abundantly than their Ly-6C+ counterparts.7,12,19,23 This may not be due to failure to exit the vasculature, because Ly-6Clo monocytes appear to emigrate out of the bloodstream very early during at least some inflammatory reactions,18 although arriving late in others.20 Human CD16+ monocytes traverse endothelium as readily as CD16− human monocytes in vitro, but their retention in model tissues is poor,24 possibly consistent with in vivo observations in mice of relatively poor accumulation of Ly-6C10 monocytes in tissues.

To probe whether the relative conservation between human and mouse monocyte subsets extends beyond a handful of molecules, we assessed gene expression profiles in mouse and human monocyte subsets and applied an algorithm to compare differential gene expression patterns between the 2 major subsets of monocytes from humans and C57BL/6 mice. We uncovered 132 genes that were differentially expressed in the same pattern between the monocyte subsets in both species, significantly strengthening the proposed homology between subsets, and identifying, for example, transcription factors that are conserved in their differential expression between monocyte subsets. Our findings also uncover gene expression patterns that are not conserved between species. These findings on conserved and nonconserved patterns may be used to delineate conditions under which the mouse is and is not useful for modeling the behavior of human monocyte subsets.

Methods

Blood from healthy human volunteers was drawn and monocyte analysis was carried out in accordance with approval from the Program for Protection of Human Subjects at Mount Sinai School of Medicine or the human ethics committee at the German Research Center for Environmental Health. Informed consent was given for drawing blood in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Experiments with mice were conducted in accordance with approvals by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Mount Sinai School of Medicine or the German Animal Protection Law ethics committee at Friedrich-Schiller University.

Microarray analysis

Humans.

We used RosetteSep (StemCell Technologies) to enrich total monocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from venous heparinized blood of healthy volunteers. The parental populations of RosetteSep-purified monocytes had purities of 88.1%, 93.4%, and 85.7% for the 3 samples hybridized to the human expression arrays. From this enrichment, human monocyte subsets were isolated using magnetic-activated cell sorting technology (Miltenyi Biotec). CD14++CD16− monocyte cells were depleted of CD16+ cells using anti-CD16 microbeads on LD columns, followed by positive selection with anti-CD14 microbeads on MS columns. For CD14+CD16+ monocyte isolation, natural killer cells were depleted with anti-CD56 microbeads on LD columns, followed by positive selection with anti-CD16 on MS columns. Purity was confirmed by flow cytometry with CD45-Phycoerythrin Cyanin 5/CD14–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/CD16–phycoerythrin (PE) staining and was found to be higher than 90% (Figure 1A). Cells (3-4 × 106/sample) were lysed with TRI-reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at −80°C. Linear acrylamide (10 μg; Ambion) was added to lysates and RNA was isolated by phenol/chloroform extraction and precipitation. Per sample, 1 μg of total RNA was processed using Ambion's MessageAmp II Biotin Enhanced labeling kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Biotinylated cRNA (15 μg) was hybridized to Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChips, which were stained, washed, and scanned following Affymetrix standard procedures.

Mice.

Leukocyte pools from 5 C57BL/6 male mice 12 weeks of age, bled by cardiac puncture, were subjected to red blood cell lysis and monocyte subsets were sorted with a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) at the Institute of Immunology at the University of Jena Medical School with assistance from Thomas Kamradt and Kerstin Bonhagen. Mouse monocytes were identified by staining with anti-CD115 (eBioscience) and anti-F4/80 antibody (Serotec) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)5 after low side scatter cells were gated to exclude granulocytes (Figure 1B). This staining scheme was chosen because an alternative staining scheme that centers on CD11b as the major identifier for monocytes4 resulted in significant NK cell contamination (data not shown). Monocyte subsets were identified by staining with anti–Gr-1 antibody (BD Biosciences) to identify Gr-1/Ly-6C–negative and –positive subsets3,5 (Figure 1B). Anti–Gr-1 mAb clone RB6-8C5 recognizes Ly-6C and Ly-6G, but only Ly-6C serves as an identifier for monocyte subsets.4,9 For mouse monocyte sorting, blood leukocytes were also stained with anti-B220 antibody (BD Biosciences) to identify and gate out B cells (not shown). Sorting was performed 4 separate times, producing 8 (4 Gr-1lo and 4 Gr-1+) biologic samples for individual array hybridizations. Sorted samples were pelleted and immediately resuspended in TRIzol (Invitrogen) and stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. RNA was isolated with RNeasy Micro-RNA isolation kit (QIAGEN), with the exception that QIAGEN kit spin filters were replaced with Zymo-Spin IC columns (Zymo Research). RNA was quality controlled using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser (Agilent Technologies). RNA amplification, direct labeling, hybridization, and slide scanning were carried out as described earlier,25 with slight modifications. We increased the in vitro transcription time from 4 to 64 hours and added fresh nucleotides and T7 polymerase, alternating every 8 and 16 hours. Finally, 2.1 μg of fragmented cRNA was hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip 430 2.0 arrays.

Analysis.

Raw human and mouse microarray CEL files were analyzed using ArrayAssist 5.5.1 expression analysis software (Version 4.0; Stratagene) and data were normalized and filtered using the gene chip robust multiarray averaging processing algorithm. Using an unpaired t test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction, we identified 427 probe sets differentially expressed between the 2 human monocyte subsets and 808 probe sets differentially expressed between the 2 mouse monocyte subsets, with a fold change of at least 2 and a P value less than .05. Further, we filtered our probe set lists where at least 5 of 8 and 4 of 6 probe sets were expressed in the mouse or human arrays, respectively, using MAS5 analysis to determine present/absent calls resulting in the identification of 338 and 693 probe sets in human and mouse, respectively. The expression data are published in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data bank, accession no. GSE17256 (mouse) and GSE18565 (human).26

Protein verification

Human.

To analyze human monocyte protein expression, PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Paque PLUS (Pharmacia, Sigma-Aldrich) gradient and washed in Ca2+-free Hanks buffered saline 3 times to remove platelets. Nonspecific antibody binding was blocked by incubation in 5% human serum and human monocyte subsets were identified by staining with anti-CD14 and anti-CD16 antibodies, along with other markers of interest (Table 1). A BD FACS Canto Flow Cytometer or a BD LSR II Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used to acquire flow cytometric data. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Mouse.

To analyze mouse monocyte protein expression, whole blood from C57BL/6J male mice (The Jackson Laboratory), 12 weeks of age, was obtained either by terminal cardiac puncture or nonterminal submandibular puncture, and was then subjected to red blood cell lysis with Pharmlyse (BD Biosciences) before staining with anti-CD115, anti–Gr-1, and other markers of interest (Table 1).

Results

We purified monocyte subsets from human and mouse blood (Figure 1) for gene expression analysis using Affymetrix gene arrays. Using ArrayAssist software to initially analyze our gene chip data, we identified 269 genes in humans and 561 genes in mice that were differentially expressed 2-fold or higher between the monocyte subsets in each species (data deposited in GEO, accession numbers GSE17256 and GSE18565). These initial data were verified by analysis of 9 differences in each species by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR; Figure 2). As the purpose behind these qPCR analyses was solely to confirm the results from the arrays, we did not focus on the same set of genes in the 2 species.

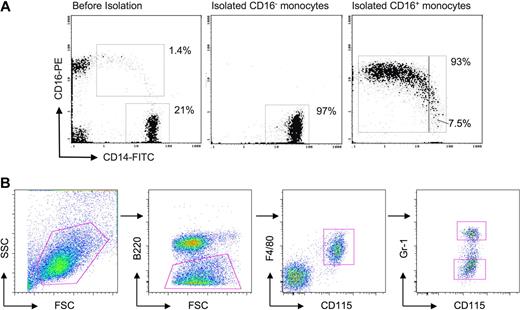

Purification of human and mouse monocyte subsets. (A) Dot plot on the left shows staining of PBMCs for human monocytes before isolation of CD16− and CD16+ subsets. Middle and right dot plots show representative samples of isolated human monocyte subsets, revealing purities of 93% or greater. The purified CD14+CD16++ cells contained 7.5% intermediate monocytes in this example. (B) In mouse whole blood leukocyte preparations, SSC-H voltage was set to exclude a majority of granulocytes and low SSC-H cells were gated (first dot plot). B220+ cells were excluded (second dot plot) and subsequent gating on CD115+ F4/80+ cells selectively identified monocytes (third dot plot). Ly-6C+ and Ly-6Clo monocyte subsets were identified by staining with anti–Gr-1 antibody, which recognizes both Ly-6G and Ly-6C (last dot plot). Only Ly-6C is expressed on monocytes. Ly-6C+/Gr-1+ and Ly-6Clo/Gr-1lo monocyte subset postsort purity was 95% to 97% (not shown).

Purification of human and mouse monocyte subsets. (A) Dot plot on the left shows staining of PBMCs for human monocytes before isolation of CD16− and CD16+ subsets. Middle and right dot plots show representative samples of isolated human monocyte subsets, revealing purities of 93% or greater. The purified CD14+CD16++ cells contained 7.5% intermediate monocytes in this example. (B) In mouse whole blood leukocyte preparations, SSC-H voltage was set to exclude a majority of granulocytes and low SSC-H cells were gated (first dot plot). B220+ cells were excluded (second dot plot) and subsequent gating on CD115+ F4/80+ cells selectively identified monocytes (third dot plot). Ly-6C+ and Ly-6Clo monocyte subsets were identified by staining with anti–Gr-1 antibody, which recognizes both Ly-6G and Ly-6C (last dot plot). Only Ly-6C is expressed on monocytes. Ly-6C+/Gr-1+ and Ly-6Clo/Gr-1lo monocyte subset postsort purity was 95% to 97% (not shown).

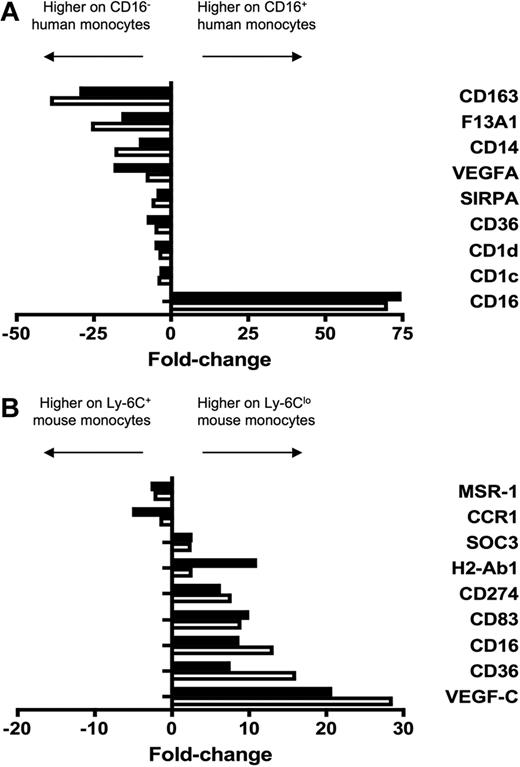

Verification of human and mouse microarray data. To verify differential expression between monocyte subsets revealed by microarray analysis, 9 genes were amplified from (A) human and (B) mouse monocyte subsets by qPCR. Results from qPCR (■) and microarray (□) are depicted as relative fold change, where negative values are more highly expressed on the CD16− human or Ly-6C+ mouse monocyte subset and positive values are more highly expressed on the CD16+ human or Ly-6Clo mouse subset. qPCR results were in good agreement with microarray data.

Verification of human and mouse microarray data. To verify differential expression between monocyte subsets revealed by microarray analysis, 9 genes were amplified from (A) human and (B) mouse monocyte subsets by qPCR. Results from qPCR (■) and microarray (□) are depicted as relative fold change, where negative values are more highly expressed on the CD16− human or Ly-6C+ mouse monocyte subset and positive values are more highly expressed on the CD16+ human or Ly-6Clo mouse subset. qPCR results were in good agreement with microarray data.

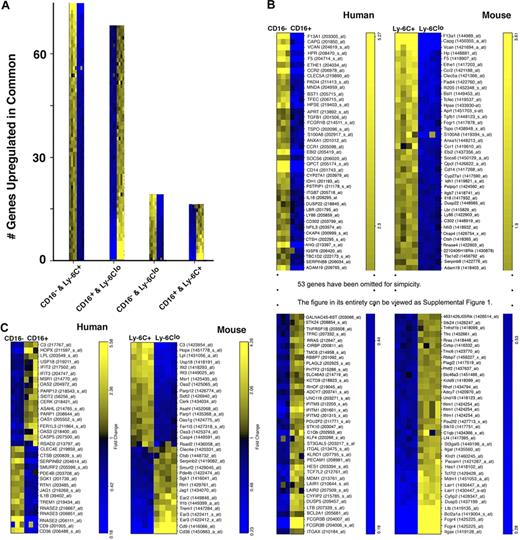

To determine how human and mouse monocyte subsets compared, we next used an ordered list algorithm27,28 to reveal cross-species gene expression conservation. The ordered sort algorithm computes a similarity score (higher scores denote increased degree of similarity) between 2 compared gene lists after searching for gene ranks that are comparable and statistically significant. The algorithm revealed similar expression profiles between CD16− human monocytes and the proposed complementary Ly-6C+ mouse monocyte subset and between CD16+ human monocytes compared with Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. For these matches, a similarity score of 12 069 entries from both ends of the gene rankings was derived (P < .001). One hundred thirty-two homologous pairs of genes accounted for 95% of this similarity score, with 69 of these pairs up-regulated in both CD16− human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes and 63 up-regulated in CD16+ human and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes (Figure 3A-B), greatly extending the list of genes known to be expressed in common patterns between the species' monocyte subsets. When performing the opposite analysis, CD16− human monocytes compared with mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes and CD16+ human monocytes against mouse Ly-6C+ monocytes, we also calculated a similarity score. However, fewer genes obtained weights in the latter assessment to produce the best empiric P value (.001), giving rise to a lower similarity score of 2054. Only 33 homologous pairs accounted for 95% of this score; 15 were up-regulated in CD16− human monocytes and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes, whereas 18 were up-regulated in CD16+ human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes (Figure 3A,C). Thus, these data support the hypothesis that the conservation of monocyte subsets between mice and humans is broad.

Cross-species comparison reveals extensive gene conservation between the species. Outcomes from ordered list algorithm are plotted, with each mRNA pool from 1 hybridization experiment depicted as 1 colored square, with high expression in yellow and low in blue. (A) The number of genes detected by the ordered list algorithm to be up-regulated in common when comparing human CD16− or CD16+ monocytes with mouse Ly-6C+ or Ly-6Clo monocytes. The 2 monocyte subset populations compared are shown on the x-axis under each bar graph. (B) Human and mouse gene lists are arranged to reveal matches of 79 of 132 genes between the species relative to the proposed counterparts of monocyte subsets in the 2 species. Heat map was truncated for simplicity. The entire heat map is presented as supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Data are shown in order of relative differences in gene expression profiles. (C) This panel depicts the 33 probe sets that were identified to be expressed in a pattern converse to the proposed analogy between monocyte subsets.

Cross-species comparison reveals extensive gene conservation between the species. Outcomes from ordered list algorithm are plotted, with each mRNA pool from 1 hybridization experiment depicted as 1 colored square, with high expression in yellow and low in blue. (A) The number of genes detected by the ordered list algorithm to be up-regulated in common when comparing human CD16− or CD16+ monocytes with mouse Ly-6C+ or Ly-6Clo monocytes. The 2 monocyte subset populations compared are shown on the x-axis under each bar graph. (B) Human and mouse gene lists are arranged to reveal matches of 79 of 132 genes between the species relative to the proposed counterparts of monocyte subsets in the 2 species. Heat map was truncated for simplicity. The entire heat map is presented as supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Data are shown in order of relative differences in gene expression profiles. (C) This panel depicts the 33 probe sets that were identified to be expressed in a pattern converse to the proposed analogy between monocyte subsets.

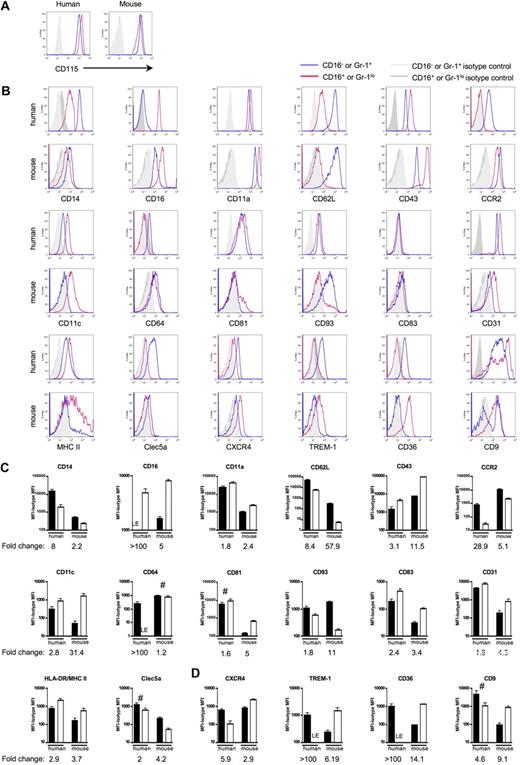

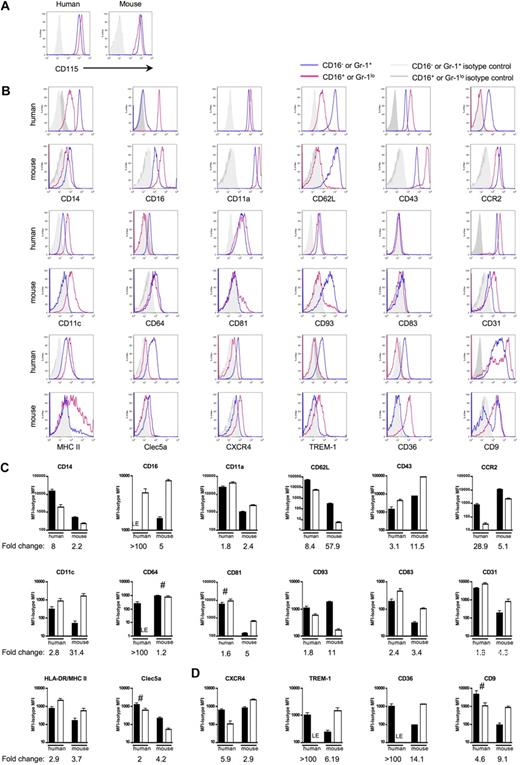

Next, we wondered whether the differential gene expression patterns revealed in the ordered list persisted at the protein level (Figure 4). First, using a panel of 18 pairs of mAbs against matched human or mouse proteins (36 mAbs in total), 35 mAbs stained the cell surface of monocyte subsets in the pattern observed for mRNA transcripts in the human or mouse arrays. One of the proteins identified by the 36 mAbs, CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) on human monocyte subsets, was not detected in the ordered list comparison, although differential expression between CD16− and CD16+ monocytes was detected at the protein level by cytometry (Figure 4B,D). CD115 (c-fms/M-CSF receptor), the only single marker currently known to be sufficient to identify mouse blood monocytes,4,5,32 was also highly expressed on both human monocyte subsets (Figure 4A). CD14 and CD16 (FcγRIII in humans; FcγRIIIa/FcγRIV in mice), the molecules traditionally used to identify human monocyte subsets,1 were similarly differentially expressed in mouse monocyte subsets, although mouse CD14 levels were much lower than in humans (Figure 4B-C). Thus, the identifying molecular signatures among mouse and human blood monocytes are conserved, and it would be appropriate in both species, for example, to name monocytes as CD16− and CD16+ subsets and to use CD115 as a monocyte marker.

Human and mouse gene conservation is preserved at the protein level. Pairs of mAbs that recognize proteins encoded by human and mouse orthologs were used to stain human or mouse monocytes. Monocytes were analyzed using the gating strategy shown in Figure 1B. (A) Representative flow plots depict CD115 (M-CSF receptor/c-fms) surface expression on human and mouse monocytes. In human, these results were observed in at least 2 independent experiments and donors. CD115 was routinely used to identify mouse monocytes. (B) Representative flow plots and relevant isotype control staining of quantitative data depicted in panels C and D show differentially expressed human and mouse monocyte subset proteins. (C) Bar graphs portray the mean mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) above background (isotype control MFI was subtracted) and standard deviation of protein expression patterns that reinforce the analogy between CD16− human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes or CD16+ human and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. (D) Data show protein patterns of expression that are converse in relation to the proposed analogy between CD16− human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes or CD16+ human and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. (C-D) ■ represent CD16− human or Ly-6G+ mouse monocyte subsets and □ represent CD16+ human or Ly-6Glo mouse monocyte subsets. For proteins marked LE, some donors showed absence of expression, whereas others showed very low expression levels relative to isotype-matched control. Graphs show data from 4 to 12 human donors or 5 to 15 C57BL/6 mice. Quantification of mean fold change between the 2 subsets in each species is indicated below each graph. Unless marked with # (human CD81, Clec5a, CD9, mouse CD64), the difference in protein expression between the 2 subsets within each species is significant; P < .05 for human CD93 and mouse MHC II, and P < .02 for all remaining human and mouse proteins, Student t test.

Human and mouse gene conservation is preserved at the protein level. Pairs of mAbs that recognize proteins encoded by human and mouse orthologs were used to stain human or mouse monocytes. Monocytes were analyzed using the gating strategy shown in Figure 1B. (A) Representative flow plots depict CD115 (M-CSF receptor/c-fms) surface expression on human and mouse monocytes. In human, these results were observed in at least 2 independent experiments and donors. CD115 was routinely used to identify mouse monocytes. (B) Representative flow plots and relevant isotype control staining of quantitative data depicted in panels C and D show differentially expressed human and mouse monocyte subset proteins. (C) Bar graphs portray the mean mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) above background (isotype control MFI was subtracted) and standard deviation of protein expression patterns that reinforce the analogy between CD16− human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes or CD16+ human and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. (D) Data show protein patterns of expression that are converse in relation to the proposed analogy between CD16− human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes or CD16+ human and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. (C-D) ■ represent CD16− human or Ly-6G+ mouse monocyte subsets and □ represent CD16+ human or Ly-6Glo mouse monocyte subsets. For proteins marked LE, some donors showed absence of expression, whereas others showed very low expression levels relative to isotype-matched control. Graphs show data from 4 to 12 human donors or 5 to 15 C57BL/6 mice. Quantification of mean fold change between the 2 subsets in each species is indicated below each graph. Unless marked with # (human CD81, Clec5a, CD9, mouse CD64), the difference in protein expression between the 2 subsets within each species is significant; P < .05 for human CD93 and mouse MHC II, and P < .02 for all remaining human and mouse proteins, Student t test.

Figure 4C summarizes cell surface staining that confirmed observations made in the arrays and that showed similar protein expression patterns for the proposed human and mouse monocyte counterparts. Although conserved appropriately between monocyte subsets, the degree of differential expression, or fold change, between the subsets within each species varied starkly for some of these proteins examined, including CD16, CD62L, CCR2, CD11c (integrin αx; Itgax), CD64 (FcγRI), and CD93. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II expression in mouse monocytes was observed on some but not all Ly-6Clo monocytes (Figure 4B-C), and it was largely absent on mouse Ly-6C+ monocytes. By comparison, human monocytes were uniformly positive for MHC II, with somewhat higher levels on CD16+ monocytes24,33 (Figure 4B-C). In contrast to the proteins analyzed in Figure 4C, Figure 4D summarizes the MFI of cell surface molecules that were identified in the ordered sort algorithm as being differentially expressed between the subsets in a pattern distinct from the proposed human and mouse monocyte counterparts (Figure 3C), including striking differences in CXCR4; TREM-1, which activates cells for proinflammatory cytokine release34 ; scavenger receptor CD3635 ; and tetraspanin CD9 (Figure 4D).

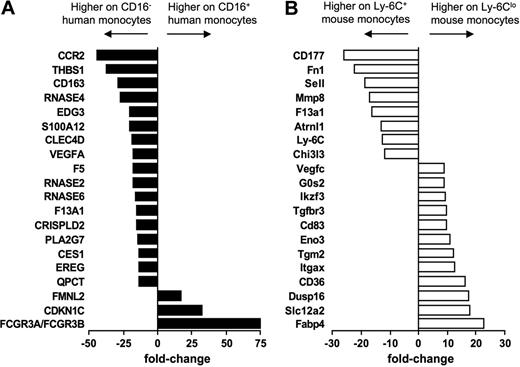

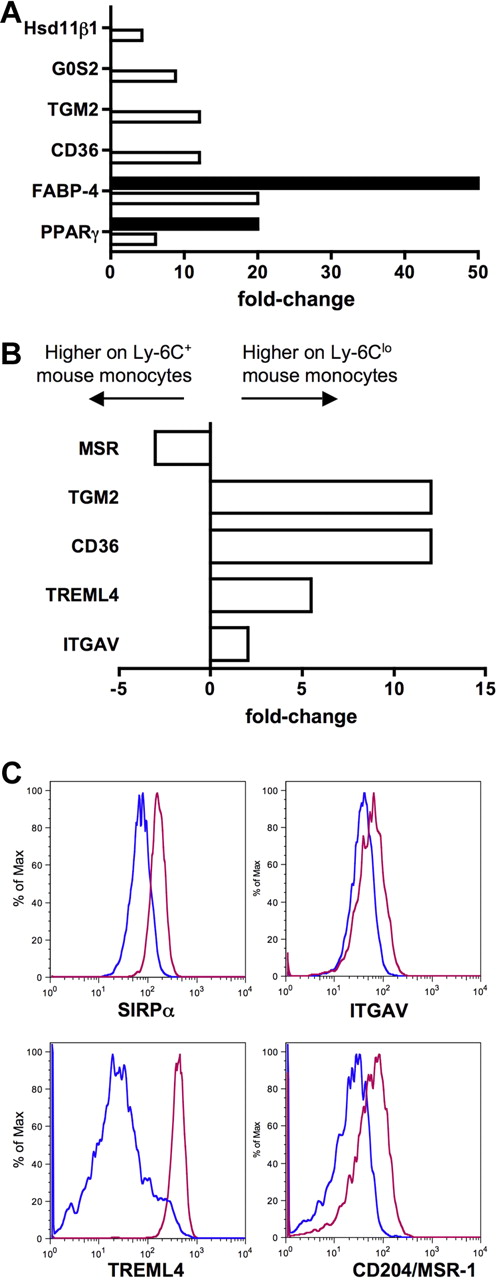

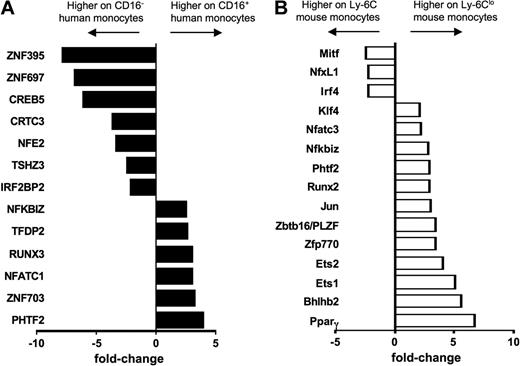

In addition to identifying genes that were expressed in common by human and mouse monocytes and their subsets, we observed patterns of gene expression that were evident only in 1 species. Figure 5 summarizes the top 20 genes differentially expressed between the subsets in humans (Figure 5A) and mice (Figure 5B). It is more difficult to interpret the meaning of genes expressed in only 1 species in relation to the overall conservation between mice and humans, because differences in the gene chips used to generate the data might artificially bias against some genes in 1 species. Furthermore, some genes in one species have no clear ortholog in the other (such as Ly-6C in the mouse). Nonetheless, these lists highlight potentially key differences between the species, as they reveal several genes that are strongly differentially expressed in one species but that are not obviously conserved in the other species. In particular, the most differentially expressed genes between mouse Ly-6C+ and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes include fatty acid binding protein 4 (Fabp-4) and its transcriptional regulator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ; Figures 5 and 6A), along with other genes previously described in human or mouse cells to be modulated by PPARγ agonists (Figure 6A), including CD3636 (Figures 5 and 6A), Hsd11β1,37 and G0S238 (Figures 5 and 6A). By contrast, no PPARγ signature was evident in the human monocyte array, consistent with follow-up qPCR analysis that failed to reveal PPARγ in human monocyte subsets (data not shown) and previous reports that PPARγ is absent in freshly isolated human monocytes.39 Thus, an active PPARγ signature prominently distinguished mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes from CD16+ human monocytes (Figures 5 and 6A).

Human and mouse monocyte subset arrays reveal some divergence from conservation. Bar graphs summarize the top 20 most differentially expressed genes between (A) human (■) and (B) mouse (□) monocyte subsets. Results are depicted as relative fold change, as determined by microarray, where negative values are more highly expressed on the CD16− human or Ly-6C+ mouse monocyte subset and positive values are more highly expressed on the CD16+ human or Ly-6Clo mouse subset.

Human and mouse monocyte subset arrays reveal some divergence from conservation. Bar graphs summarize the top 20 most differentially expressed genes between (A) human (■) and (B) mouse (□) monocyte subsets. Results are depicted as relative fold change, as determined by microarray, where negative values are more highly expressed on the CD16− human or Ly-6C+ mouse monocyte subset and positive values are more highly expressed on the CD16+ human or Ly-6Clo mouse subset.

Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes express gene signatures not found in the human subset counterpart. (A) Bar graph depicts results from qPCR (■) and microarray (□) as relative fold change of PPARγ and PPARγ-regulated genes in mouse monocyte subsets. (B) Bar graph displays results from microarray as relative fold change of genes important for recognition and engulfment of apoptotic cells in mouse monocyte subsets. (C) Protein surface expression of selected proteins from panel B are depicted as representative flow plots. In bar graphs, negative values are more highly expressed on Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes and positive values are more highly expressed on Ly-6Clo monocytes.

Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes express gene signatures not found in the human subset counterpart. (A) Bar graph depicts results from qPCR (■) and microarray (□) as relative fold change of PPARγ and PPARγ-regulated genes in mouse monocyte subsets. (B) Bar graph displays results from microarray as relative fold change of genes important for recognition and engulfment of apoptotic cells in mouse monocyte subsets. (C) Protein surface expression of selected proteins from panel B are depicted as representative flow plots. In bar graphs, negative values are more highly expressed on Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes and positive values are more highly expressed on Ly-6Clo monocytes.

Another cluster of functionally related genes that were up-regulated in mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes were those previously described to be involved in the recognition or engulfment of apoptotic cells (Figure 6B), including CD36,40 Tgm2,41 Treml4,31 and the αv integrin (ITGAV, CD51).40 This finding fits well with recent observations that this subset of monocytes preferentially engulfs dying cells administered intravenously.42 The αv integrin and Treml4 were also more highly expressed on mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes at the protein level (Figure 6C), in addition to the apoptotic cell recognition molecule SIRPα,40 which was not differentially expressed at the mRNA level in mice but was conversely expressed in human monocyte subsets (Figure 2A). Furthermore, macrophage scavenger receptor 1 (Msr-1; scavenger receptor A, CD204) was more highly expressed on the surface of mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes (Figure 6C), though the pattern of mRNA in the mouse subsets was opposite (Figure 6B), and the expression of MSR-1 between human monocyte subsets is also converse to mouse subset expression (Figure 3).43 Collectively, it appears that a major difference between mouse and human monocyte subsets is the relative concentration of classical scavenger receptors and apoptotic cell recognition molecules on Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. In humans, these receptors are either more highly expressed on CD16− monocytes (SIRPα, MSR-1, CD36, and thrombospondin 1/Thbs1; Figures 2,Figure 3,Figure 4–5) or not differentially expressed.

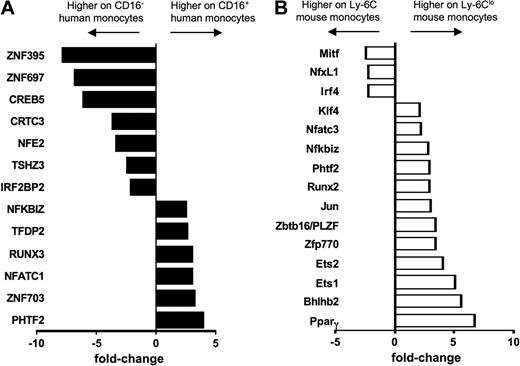

Finally, differential expression of transcription factors in monocyte subsets between mice and humans has never been explored. The strong differential expression of PPARγ in mouse monocyte subsets prompted us to examine the overall pattern of well-characterized transcription factors between monocyte subsets in the 2 species. From the ordered list analysis (Figure 3), we identified transcription factor EC (Tcfec/TFEC)44 as elevated in human CD16− and mouse Ly-6C+ monocytes and TCF7L2 (TCF4), a member of the Wnt signaling pathway that participates critically in type II diabetes,45 and Pou2f2/Oct2 as elevated in both human CD16+ and mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes (Figure 3B). Hoxb was also differentially expressed in monocyte subsets of both species, but in a converse pattern when comparing human and mouse monocytes (Figure 3C). Beyond PPARγ (Figure 6A), a variety of other transcription factors or regulators were observed in only 1 of the 2 species (Figure 7). It remains to be determined, however, whether these differences coordinate fundamentally distinct behaviors of monocyte subsets in physiologic or pathologic settings or whether the different transcription factors ultimately drive similar expression patterns between the 2 species.

Transcription factors not shared between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Bar graph depicts results from microarray as relative fold change of transcriptional regulators in (A) human and (B) mouse monocyte subsets, where negative values are more highly expressed on the CD16− human or Ly-6C+ mouse monocyte subset and positive values are more highly expressed on the CD16+ human or Ly-6Clo mouse subset.

Transcription factors not shared between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Bar graph depicts results from microarray as relative fold change of transcriptional regulators in (A) human and (B) mouse monocyte subsets, where negative values are more highly expressed on the CD16− human or Ly-6C+ mouse monocyte subset and positive values are more highly expressed on the CD16+ human or Ly-6Clo mouse subset.

Discussion

Here, we used Affymetrix whole genome microarrays to compare differential gene expression patterns between the 2 major subsets of monocytes in humans and C57BL/6 mice. We then used an ordered listed algorithm to compare monocyte subset gene expression patterns across species (Figure 3) and verified our findings by flow cytometry (Figure 4). Our data add more than 100 genes to the list of those that are conserved between CD16− human monocytes and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes and between CD16+ human monocytes and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. These findings greatly extend the previous identification of approximately 8 similarities used to argue for analogy between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Molecules used to identify monocytes in the 2 species, including CD115, CD14, and CD16, were also conserved, leading us to suggest that it would be appropriate to refer to monocytes as CD16− and CD16+ subsets in both species and to use CD115 as a monocyte marker in humans as it is used in mice.

The similarities we uncovered likely underrepresent the actual conservation between human and mouse monocyte subsets, possibly because the stringency of the criteria used to analyze the data likely excludes detection of some differentially expressed genes. For example, it is known that CD33 is differentially expressed on the surface of human monocyte subsets.46 This gene was not revealed in our cross-species comparative analysis despite that the mouse array showed elevated CD33 mRNA in Ly-6C+ monocytes compared with Ly-6Clo monocytes, strongly suggesting that the mouse mirrors the human for this molecule.

This study also clarifies some previously described discrepancies in the expression patterns of some molecules on monocyte subsets. First, our gene array and cell surface staining for CD31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1) revealed higher CD31 levels on human CD16+ and mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes, although previous staining for CD31 revealed a different pattern.3 Second, we confirmed that CD11c is indeed expressed on mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes, consistent with several laboratories' surface staining for this protein,4,12,16,17 and therefore revealing a conserved pattern of elevated CD11c in human CD16+ and mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes. The lack of differentially expressed CD11c observed in a previous mouse monocyte subset array may be due to the higher variability among replicate samples, different microarray technology, or the fact that the gene expression profiling was previously carried out in CX3CR1gfp knock-in mice lacking 1 copy of CX3CR1.18 Finally, we clarify expression of MHC II among mouse monocytes. From the array analysis, genes encoding MHC II (I-Ab) and related histocompatibility molecules were highly enriched in mouse Ly-6Clo monocytes, fitting in kind with higher MHC II expression in human CD16+ monocytes.24,33 However, though a correlation between the ability to promote mixed lymphocyte reaction has been made between mouse and human Ly-6Clo and CD16+ monocytes, respectively,5,47 MHC II expression on mouse monocytes has remained uncertain. Our findings indicate that a subset of Ly-6Clo monocytes express MHC II.

Our ordered list approach detected a smaller number of molecules that, although remaining differentially expressed between monocyte subsets, diverged in their expression patterns from the proposed mouse and human monocyte counterparts. These included CXCR4, TREM-1, CD36, and CD9 (Figures 2,Figure 3–4). Perhaps more profound was the presence in Ly-6Clo monocytes of a strong PPARγ activity signature not seen in either human monocyte subset. The difference in lipid ligand-activated PPARγ expression and activity and divergent patterns of CD36 expression may suggest particular differences between the species' circulating monocytes in lipid responses. However, potentially arguing in favor of conserved function, despite distinct expression patterns in these pathways, is the preferential uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein by CD16+ human monocytes in the context of familial hyperlipidemia48 and Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes in an experimental model of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis.16

One of the cardinal features of blood monocytes is their phagocytic capacity. Our array analysis may provide important insight into differences between the mouse and human monocyte subsets with regard to this important function. From past studies, circulating Ly-6Clo monocytes appeared to have an advantage in capturing intravenous polystyrene spheres and heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae.7,49,50 A recent investigation of human monocyte subsets using both proteomic and transcriptomic analyses suggests that human CD16+ monocytes possess a greater phagocytic capacity, but functional assessments were not made.21 In contrast, CD16− human monocytes, but not CD16+ human monocytes, were able to take up plain nanoparticles, leading the authors to conclude that, in contrast to their mouse counterparts in vivo, CD16+ human monocytes were not phagocytic.51 As a likely explanation, the data from our array strongly indicate that phagocytic recognition receptors are markedly different in expression patterns between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Several receptors, including CD36, MSR-1, SIRPα, and thrombospondin 1, appear enriched on human CD16− monocytes by surface protein and/or mRNA analysis (Figures 2,Figure 3,Figure 4–5), whereas all of these molecules and others involved in recognition of dying cells (Treml431 ) are enriched on Ly-6Clo mouse monocytes. Moreover, even where similarity between the species was detected, an argument can be made that functional differences may still exist. For example, CD64 (FcγR1) was conserved between human and mouse monocyte subsets, with its mRNA and protein most elevated in CD16− human and Ly-6C+ mouse monocytes. However, in humans, CD64 surface protein was absent on CD16+ monocytes, whereas in the mice, Ly-6Clo monocytes were still positive with only a slightly reduced expression of plasma membrane CD64 relative to their Ly-6C+ counterparts. Thus, to some extent, CD64 is actually differentially expressed among human and mouse “CD16+ monocytes,” such that responses to opsonized and unopsonized phagocytic material by this subset in the 2 species in vivo may be very different.

As shown herein, a gene expression analysis of this type can be highly informative when it comes to defining homologues in different species. When looking at functional implications it is, however, an inherently descriptive approach that is meant to provide a foundation on which to build future work. A species comparison of this type is useful for making predictions about which pathways, and even which molecules, in a mouse may be most relevant to the behavior of human monocytes in physiology and disease. Caution should always be exercised when making assumptions across species, however we have already found these data useful in shaping our own focus in ongoing projects. In summary, this comparative analysis brings forward a database that has the potential to provide important insight for the use of mouse models as a surrogate for the study of human monocyte behavior in vivo.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeffrey Ravetch, Ralph Steinman (Rockefeller University), and Matthias Mack (University of Regensburg) for gifts of anti–mouse mAbs FcgRIV/CD16, Treml4, and CCR2, respectively. We are grateful to the staff of the flow cytometry cores at Mount Sinai and Friedrich Schiller University for expert assistance with cell sorting. We also thank Marcus Hildner, Christine Ströhl, Thomas Kamradt, and Kerstin Bonhagen (Friedrich Schiller University) and Ted Kaplan, Van Anh Nguyen, Chunfeng Qu, Joerg Mages, David Alvarez, and Sue Babunovic (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) for technical assistance and/or generation of data that led to this study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI061741 and AI049653 and Established Investigator Award 074052 from the American Heart Association (G.J.R.), a DFG project grant (ZI 288; L.Z.H.), DFG project grant SP713/4-1 (R.S.), and National Institutes of Health postdoctoral training grant T32 DK7757-10 (M.A.I.) and 1F32HL096291-01 (individual National Research Service Award; M.A.I.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.I. and R.S. designed, conducted, and analyzed experiments and wrote the paper; C.L. analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the paper; E.L.G., M.F., R.H., R.L., M.H., M.C., and F.T. designed and conducted experiments and analyzed data; A.J.R.H. designed and interpreted experiments; and L.Z.-H. and G.J.R. designed and interpreted experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current address for F.T. is Department of Medicine III, RWTH-University Hospital Aachen, Pauwelsstrasse 30, 52074 Aachen, Germany.

Correspondence: Gwendalyn J. Randolph, Department of Gene and Cell Medicine and the Immunology Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1425 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10029; e-mail: gwendalyn.randolph@mssm.edu; or Loems Ziegler-Heitbrock, Asklepios-Fachklinik and Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Robert-Koch-Allee 29, 82131 Gauting, Germany; zieglerheitbrock@helmholtz-muenchen.de.