Abstract

We assessed frequency and predictive factors for major cardiovascular (CV) events in 707 patients with primary myelofibrosis (PMF) followed in 4 European institutions. A total of 236 deaths (33%) were recorded for an overall mortality of 7.7% patient-years (pt-yr). Fatal and nonfatal thromboses were registered in 51 (7.2%) patients, with a rate of 1.75% pt-yr. If deaths from non-CV causes were considered as competing events, we estimated that the adjusted rate of major thrombotic events would have been 2.2% pt-yr. In a multivariable model, age older than 60 years (hazard ratio [HR], 2.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24-4.39, P = .01) and JAK2 mutational status (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.10-3.34; P = .02) were significantly associated with thrombosis, whereas the strength of the association between leukocyte count higher than 15 × 109/L and CV events was of borderline significance (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 0.97-2.72; P = .06). The highest incidence of fatal and nonfatal thrombosis was observed when the mutation was present along with leukocytosis (3.9% pt-yr; HR, 3.13; 95% CI, 1.26-7.81). This study is the largest hitherto carried out in this setting and shows that the rate of major CV events in PMF is comparable with that reported in essential thrombocythemia, and it is increased in aged patients and those with JAK2 V617F mutation and leukocytosis.

Introduction

The classic Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) include polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF). At variance with PV and ET, PMF is characterized by a progressive clinical course and a shortened life expectancy, with median survival after diagnosis of less than 5 years.1 Main causes of morbidity and mortality are usually the result of leukemic transformation, infection, bleeding, portal hypertension, as well as vascular complications.2 Until now, the incidence of fatal and nonfatal thrombosis in PMF and the risk factors for such complication have been assessed only in a single series,3 because the rarity of the disease and the low number of vascular events prevented reliable evaluation in terms of epidemiology and prognostic relevance. In fact, most studies so far produced of PMF aimed at identifying risk factors associated with a significant excess of mortality, with the purpose to stratify patients to different therapies.4-6 In this sense, although several prognostic scores have been proposed in PMF,2,7-9 the variables considered were specifically directed to explain the cause of death and do not fully explain which risk factors are involved in the development of cardiovascular complications.10,11 Moreover, the majority of studies on this topic have some limitations, such as retrospective design, a relatively small number of patients, and, in many instances, lack of an objectively proven diagnosis of vascular complications. In addition, the variables included in multivariable models were often incomplete, thus, the recent data regarding the new disease-related risk factors for thrombosis in MPNs12-14 were rarely considered.

In the present study, the frequency and risk factors of major vascular complications have been estimated in 707 unselected PMF patients monitored in routine clinical practice from 4 European institutions, for whom accurate follow-up data were available. Herein we provide the profile of the disease in terms of incident thrombotic events and identify major associated risk factors, with the final goal to better characterize this important medical need.

Methods

After approval from the Institutional Review Board of each participating study center, a cohort of 707 PMF patients was collected in 3 Italian (Bergamo, Florence, Pavia) and 1 Spanish (Barcelona) institutions during the period of February 1973 to December 2008. Diagnosis of PMF was made according to the criteria accepted at the time when the patients were diagnosed.15-17 The usual practice of these institutions was to visit patients at least every 3 months. Pertinent data were collected in each center and sent to Bergamo for analysis. Each database was set up to include all events occurring after diagnosis. For the purpose of the present study, the so-called “prefibrotic” form of PMF18 as well as post–polycythemia vera (post-PV) or post–essential thrombocythemia (post-ET) myelofibrosis19 were not considered.

Definition of outcome events

We examined survival, the rate of cardiovascular (CV) and non-CV death, and the rate of fatal and nonfatal arterial and venous thrombosis. The category of CV-related death included documented diagnosis of myocardial infarction or stroke in the absence of any other evident cause, sudden death, death from heart failure, and all deaths classified as CV in nature.

Myocardial infarction was defined as at least 2 of the following: chest pain of typical intensity and duration; ST segment elevation or depression of (1) 1 mm or more in any limb lead of the electrocardiogram (2) 2 mm or more in any precordial lead, or (3) both; or at least a doubling in cardiac enzymes. Diagnosis of stroke required unequivocal signs or symptoms of a neurologic deficit, with sudden onset and duration of more than 24 hours. Diagnosis had to be confirmed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging because these were the available tools. Transient ischemic attack was defined as the abrupt onset of unilateral motor or sensory disturbance, speech defect, homonymous hemianopsia, or transient monocular blindness that resolved completely in less than 24 hours. Pulmonary embolism was defined by a positive pulmonary angiogram, a high-probability ventilation-perfusion scan. Deep vein thrombosis was defined as a typical clinical picture with positive instrumental investigation (phlebography, ultrasonography, impedance plethysmography, and computer tomography at unusual sites). In the case of a suspected recurrence in a site of previous deep vein thrombosis, the diagnosis could be accepted if the instrumental test showed extension or recurrence of thrombosis compared with previous testing.

Statistical methods

Thrombotic fatal and nonfatal episodes occurring during the follow-up, as well as overall deaths and deaths for each cause, were calculated as rates per 100 patient-years. Because the major outcome was thrombosis-free survival from diagnosis, deaths not related to CV events were treated as competing events in this analysis. To take into account this potential bias, the crude cumulative incidence of CV fatal and nonfatal events and of deaths for other causes was calculated by fitting a competing risk model as proposed by Fine.20

The effect of the potential prognostic factors on thrombosis-free survival was evaluated by fitting various Cox regression models, considering each factor separately (univariable analysis) or adjusting for the confounding effect of the following potential confounders (multivariable analysis): (1) baseline characteristics: center, age, sex, previous thrombotic event; (2) indicators of CV morbidity: smoking, history of diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension; (3) hematologic parameters at diagnosis including hemoglobin, platelet count, and leukocyte counts; (4) Dupriez7 and International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) scores2 ; and (5) cytoreductive therapy and splenectomy as treatments registered in follow-up.

Cutoffs for hemoglobin and platelet count were chosen on the basis of the results obtained in a previous paper on this issue3 ; the best leukocyte count cutoff was derived by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis.

The final prognostic model was identified through a stepwise selection process. Initially, all potential risk factors and confounders were included in the multivariable Cox model. At each step, variables with a P value greater than the cutoff (fixed at 0.10) were excluded from the model and the remaining ones were tested again for their independent association with thrombosis-free survival until no more variables met the criteria for exclusion.

Results

The characteristics at presentation of the cohort of patients are presented in detail in Table 1 and reflect well the mix of epidemiologic and clinical features that are found in the routine clinical practice of care of unselected PMF patients in terms of age, hematologic and clinical presentation, scoring system values, and frequency of the JAK2 mutation. Patients were managed according to standard recommendations.21,22 Briefly, treatment included a watch-and-wait policy until disease progression. The most used single-chemotherapeutic agent was hydroxyurea, but busulfan, 6-mercaptopurine, and thioguanine were also used. Androgens, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, prednisone, interferon-alpha, anagrelide, immunomodulatory agents such as thalidomide and lenalidomide, and, in few instances, pomalidomide were other drugs variably used. In patients with a previous history of thrombosis, low-dose aspirin or warfarin was given in arterial and venous events, respectively, in at least 90% of patients. A total of 97 patients (14%) underwent splenectomy during the study period. Patients who underwent bone marrow transplantation were also included (n = 14).

Table 2 reports the incidence and type of major vascular events. A total of 236 deaths (33%) were recorded for an overall mortality rate of 7.73 deaths per 100 patient-years. Only 2% of these deaths were due to well-documented CV causes, accounting for 0.39 deaths per 100 patient-years. The majority of deaths were due to other causes, including leukemia, infections, and transplantation-related causes. The cumulative rate of fatal and nonfatal CV events was 7.2%, accounting for 1.75 events per 100 patient-years. As for nonfatal CV events (cumulative rate of 6.6%), the incidence of myocardial infarction and peripheral arterial thrombosis was lower than that of stroke. Of note is the remarkably high rate of fatal (9 cases) and nonfatal (22 cases) venous thrombosis. In patients presenting with thrombosis at diagnosis or with a thrombotic history, the incidence of recurrences was 9% (6 of 67, 9%) and the first thrombotic event was registered in 7% of asymptomatic cases (45 of 640; P = .15).

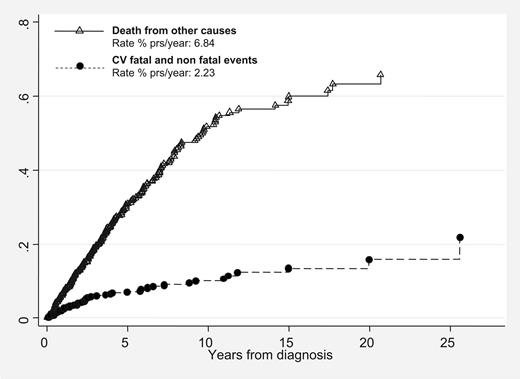

The rate of fatal and nonfatal CV complications (1.75 events % patient-years) was actually underestimated. In fact, if deaths from causes other than CV complications were considered as competing events, the frequency of major thrombotic events at 10 years would have been 2.23 events per 100 patient-years (Figure 1).

Cumulative incidence of fatal and nonfatal thrombotic events versus deaths from other causes (competing risk analysis) in 707 patients with primary myelofibrosis.

Cumulative incidence of fatal and nonfatal thrombotic events versus deaths from other causes (competing risk analysis) in 707 patients with primary myelofibrosis.

Univariable analysis for CV events (Table 3) indicated that age, Dupriez score, baseline leukocytosis greater than 15 × 109/L, and presence of the JAK2 mutation were all significantly associated with the incidence of fatal and nonfatal events. The IPSS score was of borderline significance, whereas previous thrombotic events, coexistent cardiovascular risk factors, platelet number, splenomegaly and previous splenectomy, and the use of cytoreductive therapy did not show any influence on the occurrence of CV-incident events.

In multivariable analysis (Table 4), age and JAK2 mutational status independently retained their significance, whereas the strength of the association between baseline leukocytosis and CV events became weaker and its statistical significance was borderline (P = .06). No statistically significant difference was found by separate analysis of venous and arterial events.

Table 5 shows the interaction between JAK2 V617F status and leukocytosis in terms of incidence of events. Approximately 30% of our PMF patients exhibited a combination of wild-type JAK2 and low WBC, and this group experienced 1.07 events per 100 patient-years. This frequency increased when wild-type JAK2 was associated with leukocytosis, even though it did not reach the significance level. Patients with JAK2 V617F mutation had a higher and statistically significant probability of developing future CV events compared with wild-type category. Patients who were JAK2 V617F mutated and presented leukocytosis had the highest incidence of thrombosis (3.9% pt-yr).

Discussion

Our cohort study provides an estimate of the frequency and risk factors of incident fatal and nonfatal vascular events registered in routine clinical practice in a large number of PMF patients followed up in a qualified network of international hematologic centers.

The overall cumulative rate of CV death and nonfatal thrombotic complications was 7.2%, accounting for 1.75 events % patient-years. This frequency indicates that PMF is a disease with a cardiovascular risk profile comparable with ET, in which the reported overall incidence of major vascular events ranges from 1% to 3% pt-yr.23,24 The frequency of these complications is clearly lower than in PV, in which the Efficacy and Safety of Low Dose Aspirin in Polycythemia Vera (ECLAP) observational study25 registered a rate of CV deaths and nonfatal thrombotic events of 5.5 events per 100 patient-years. However, it should be considered that the thrombotic rate in PMF could be obscured by other major fatal and nonfatal competing events such as acute leukemia transformation or other non-CV major complications. In our competing risk analysis, we calculated that the CV rate would be higher (2.33% pt-yr) if these competing events were considered in the statistical model. This observation would indicate that in PMF, as in PV and ET, a significant propensity to thrombosis is linked to the clonal myeloproliferation that definitely identifies the MPNs as thrombophilic conditions.26

In our PMF patients, a high rate of deep venous thrombosis affecting legs, brain, and splanchnic area was registered, whereas, unlike in ET and PV, the incidence of myocardial infarction was lower than that of stroke. This agrees with the results by Cervantes et al3 who calculated that, contrary to stroke and venous complications, the frequency of acute coronary syndrome in PMF does not exceed that of normal matched population; the excess of deep vein thrombosis is also confirmed in this series.

The variables selected for prognostic assessment were those previously shown to be of prognostic value in PV and ET (including leukocytosis and JAK2 V617F mutational status), those clinically meaningful in PMF, and possible confounders, including center effect. Moreover, only CV events registered during the follow-up were considered; therefore this analysis differs from other studies. Thus, in a retrospective single-institution survey, Cervantes et al3 reported 155 PMF patients with 31 thrombotic events occurring before, at, and after diagnosis, demonstrating in a multivariable model the independent prognostic role of thrombocytosis, elevated hemoglobin, and presence of cardiovascular risk factors. In contrast, in our larger PMF series, which also includes patients from the Cervantes et al study, we failed to confirm a predictive role of these factors. The discrepancy could probably be ascribed to the different number of patients, the rate of incident events, and the different variables included in the analysis.

Instead, in multivariable analysis, we have shown an independent prognostic role for age and JAK2 mutational status, whereas baseline leukocytosis was of borderline significance. We failed to demonstrate a correlation between the incidence of CV events and baseline platelet number or cardiovascular risk factors. Several studies have consistently identified advanced age (> 60 years) as a risk factor for thrombosis in both ET and PV.27 In contrast, whether the presence of cardiovascular risk factors confers additional risk is still a matter of discussion. The lack of prognostic relevance of thrombocytosis in our PMF series is not surprising because the absence of independent correlation between high platelet number and thrombosis has been confirmed in several studies in both ET and PV and, according to some authors, this notion seems to be no longer a matter of controversy.23,28

The prognostic relevance of the JAK2 V617F status in terms of cardiovascular risk in PMF has been analyzed in a recent meta-analysis,14 in which JAK2 V617F was associated with a tendency for increased risk of thrombosis (odds ratio [OR], 1.76; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-3.41), even though this difference did not reach statistical significance, most likely because the number of patients was insufficient. Here we confirm the strength of this association and, for the first time, demonstrate that the mutation has an independent statistically significant role after correction with several confounders. It should be noted that these latter results refer only to patients in whom JAK2 V617F was tested. These cases differ from JAK2 nonevaluated patients because they were younger (53 vs 59 years, respectively, P = .002) and presented a lower IPSS score (low and intermediate class: 84% vs 67%, respectively, P < .001). These patients were not selected, so we do not have a clear explanation for these findings. In any case, “JAK2 nonevaluation status” included in the multivariable model was not independently associated with thrombotic risk. Of note is the interaction between JAK2 mutational status and leukocytosis that allowed us to identify 3 groups at different prognostic vascular risk. Thus, patients with JAK2 wild type and low WBC exhibited the lowest rate of events, whereas the highest frequency was observed in the group with the mutation and leukocytosis. An intermediate risk category was identified by the presence of either leukocytosis or JAK2 mutation.

In conclusion, few epidemiologic studies have been conducted in recent years to evaluate to what extent vascular complications can influence the prognosis of PMF patients. The results of the present study represent PMF as a myeloproliferative neoplasm with a tendency to develop vascular events comparable with ET. We have also recognized an independent prognostic role for JAK2 V617F mutational status and demonstrated its interaction with leukocytosis that allows to identify groups of PMF patients with different risk levels for fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular complications. In summary, clinicians should be aware that in PMF cardiovascular complications occur at a significantly higher rate than previously believed; furthermore, these data suggest caution in prescribing immunomodulatory drugs, such as thalidomide or pomalidomide, that, per se, are associated with vascular complications.29

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr Federica Delaini for the collaboration in collecting clinical data.

This work was supported by funding from Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC; A.C. fellowship), European LeukemiaNet Sixth Framework Programme LSH-2002-2.2.0-3, MIUR-PRIN Projects (A.M.V.), Istituto Toscano Tumori (A.M.V.), Associazione Paolo Belli and Associazione Italiana Lotta alla Leucemia (AIL), sezione Paolo Belli, and RD06/0020/004 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Health (F.C.)

Authorship

Contribution: T.B. and G.F. designed and performed research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, and wrote the paper; A.C. designed and performed research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the paper; F.C., A.M.V., and G.B. designed research, interpreted data, and wrote the paper; P.G., E.A., and A.A.-L. collected data; and A.R. performed research and interpreted data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tiziano Barbui, Divisione di Ematologia, Ospedali Riuniti, Largo Barozzi 1, 24128 Bergamo, Italy; e-mail: tbarbui@ospedaliriuniti.bergamo.it.