Abstract

The vitelline artery is a temporary structure that undergoes extensive remodeling during midgestation to eventually become the superior mesenteric artery (also called the cranial mesenteric artery, in the mouse). Here we show that, during this remodeling process, large clusters of hematopoietic progenitors emerge via extravascular budding and form structures that resemble previously described mesenteric blood islands. We demonstrate through fate mapping of vascular endothelium that these mesenteric blood islands are derived from the endothelium of the vitelline artery. We further show that the vitelline arterial endothelium and subsequent blood island structures originate from a lateral plate mesodermal population. Lineage tracing of the lateral plate mesoderm demonstrates contribution to all hemogenic vascular beds in the embryo, and eventually, all hematopoietic cells in the adult. The intraembryonic hematopoietic cell clusters contain viable, proliferative cells that exhibit hematopoietic stem cell markers and are able to further differentiate into myeloid and erythroid lineages. Vitelline artery–derived hematopoietic progenitor clusters appear between embryonic day 10 and embryonic day 10.75 in the caudal half of the midgut mesentery, but by embryonic day 11.0 are sporadically found on the cranial side of the midgut, thus suggesting possible extravascular migration aided by midgut rotation.

Introduction

The first wave of embryonic hematopoiesis occurs in the yolk sac from mesodermal precursors at embryonic day 7.0.1 These early yolk sac mesodermal cells, initially termed hemangioblasts,2 were thought to have bipotentiality, giving rise to both blood and endothelium.3 The descendants of hemangioblasts form structures called blood islands,2 which consist of rounded hematopoietic cells (HCs) circumscribed by an endothelial layer. Although initially thought to propagate the entirety of the adult hematopoietic system, yolk sac hematopoiesis is not fully responsible for definitive hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) emergence but instead provides a transient immature (primitive) hematopoietic population that is later supplanted.4-6 Yet the inability of the yolk sac to produce any definitive adult HCs has recently been questioned.7,8 In addition, the concept of a mesodermal precursor to HSCs in the early yolk sac has been challenged by recent data suggesting that yolk sac hematopoiesis at the hemangioblast stage occurs through an endothelial intermediate.9,10 Thus, the yolk sac probably provides both primitive and definitive HCs, but the difference between how the 2 populations emerge and timing of their emergence is still under investigation.

Our understanding of intraembryonic definitive hematopoiesis has also been refined by a recent multitude of publications using various systems and model organisms. Previous landmark studies have demonstrated that instead of (or taking into account the more recent data: in addition to) the early yolk sac, later intraembryonic arterial sites give rise to definitive HSCs.4-6,11-13 In these sites, large clusters of HSCs are attached to the endothelium, suggesting that a specific subset of endothelial cells (ECs, hemogenic endothelium)14 are progenitors for HSCs. However, the concept of a mesodermal precursor for HSCs within these intraembryonic sites was also argued.15,16 The phenomenon of endothelial derived-blood, termed hemogenic endothelium,9,10,17-21 has become the new paradigm of HSC generation. Vascular beds commonly implicated in endothelial-derived HSC emergence include the dorsal aorta (aorto-gonado-mesonephros region [AGM]),17-22 yolk sac,21,23 placenta,21,24-26 and the vitelline and umbilical arteries.15,21,27 In the past 2 years, using various strategies from in vivo lineage tracing,21 deletion of a critical hematopoietic transcription factor (Runx1)17 in mouse endothelium, in vitro tracing and Runx1 deletion in mouse embryonic stem cells,10 to live imaging in mouse,20 zebrafish,18,19 and mouse embryonic stem cell cultures,9 multiple groups have offered unequivocal evidence that a subset of endothelium is indeed “hemogenic.” However, the hemogenic capacity is embryonic, short-lived, and restricted to specific ECs. The fact that only particular vascular beds are capable of hematopoietic emergence begs the question of vascular divergence. Why is only a subgroup of vascular endothelium, located within various sites of the embryo, within a similar gestational window, capable of hematopoiesis? It has been suggested by our group that the vascular beds that compose hemogenic endothelial sites may share a common mesodermal origin21 that is separate from other nonhemogenic endothelium. In the present study, we address this question via lineage tracing analysis.

In addition to the multiple intraembryonic hemogenic vascular sites and the yolk sac hemangioblast (now also hemogenic endothelium10 ), there is another lesser investigated site of hematopoiesis in the embryo. A meticulous mapping study of hematopoietic sites in the mouse embryo revealed the appearance of “intraembryonic blood islands” in the midgut mesentery that extends ventrally from the dorsal aorta at midgestation.28,29 The structure of these mesenteric blood islands shares similarities with those described in the yolk sac, which is that of endothelial circumscribed hematopoietic clusters. However, the origin and characterization of these structures are unknown. A current hypothesis is that they originate in situ through differentiation of mesenchymal cells, similarly to the initial hypothesis of the yolk sac blood islands.28 The mesenteric blood islands are also in the same vicinity of specific mesodermal cells shown to express HSC surface antigens and initially thought to be responsible for AGM hematopoiesis.16,22 Yet it remains unclear how the mesenteric blood islands arise in midgestation, whether they give rise to functional HSCs, and how their emergence differs from other hemogenic vascular beds, including the early yolk sac.

In this study, we demonstrate that the previously described mesenteric blood islands are not derived in situ but instead arise as a direct result of extensive vascular remodeling of the vitelline artery,28 and are endothelial-derived. In addition, we demonstrate that the vitelline artery and its hematopoietic derivatives (mesenteric blood islands) belong to the subset of vascular beds that have hematopoietic capacity (eg, hemogenic endothelium) and that these hemogenic vascular beds share a common origin derived from lateral plate mesoderm.

Methods

Animals

Animal protocols were conducted in accordance with University of California at Los Angeles Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine's Animal Research Committee guidelines. VE-cadherin Cre30 (VE-cad Cre) and HoxB6 Cre31 were crossed to R26R Cre reporter lines with LacZ reporter32 and separately EYFP reporter.33 Runx-1 LacZ reporter lines were bred separately.34 Pregnancies were dated by presence of a vaginal plug (day 0.5 of gestation).

β-Galactosidase staining and immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining, β-galactosidase, semithin, and electron microscopy protocols were previously described.30,35,36 Tissue sections underwent immunostaining with the following antibodies: CD41 1:100 (Abcam), Ikaros 1:100 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cleaved caspase-3 1:100 (Cell Signaling Technologies) and phospho-histone-H3 1:100 (Cell Signaling Technologies), and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) nuclear stain. Alternatively, vibratome sections (300 μm) underwent β-galactosidase as referenced above. All fluorescent immunohistochemistry (EYFP, Cy3, AlexaFluor-546 and -568 fluorophores) was analyzed using a Bio-Rad confocal MRC1024 or a Zeiss LSM 510 multiphoton microscope (10×/0.45NA, 25×/0.8NA, 40×/1.3NA oil, and 63×/1.4NA oil objectives), acquired with Zen 2009 software (Carl Zeiss), analyzed with Axiovision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss). Bright-field micrographs were taken with an Olympus BX40 (histologic sections, 10×/0.30NA, 20×/0.80NA, and 40×/1.00NA oil objectives) or Olympus SZX12 (whole-mount, 7× to 20×) microscope using an Olympus DP25 camera and analyzed with Magnafire 2.0 (Optronics) Axiovision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss). All photographic images were analyzed after acquisition using Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems).

Colony assays

Vitelline arteries and fetal livers from E10.0 to E11.5 were dissected, mechanically dissociated, and subsequently cultured in methylcellulose assays as described.21 Cells were plated at a density of 4 × 103/mL, with Methocult media (StemCell Technologies). Colonies were scored by light microscopy after 10 days of plating.

FACS analysis and antibodies

Vitelline arteries and fetal livers were mechanically dissociated and filtered (40 μm). Cells were evaluated for β-galactosidase by hypotonic loading of fluorescein di-D-galactopyranoside (FDG) as described,21 and incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated CD34, allophycocyanin-conjugated c-kit and analyzed on a FACSCalibur with the appropriate isotype controls. 7-Amino-actinomycin D was used as a viability dye. Antibodies and isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences PharMingen.

Optical projection tomography scanning

Embryos were stained for β-galactosidase and postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Stained and fixed samples were embedded in 1.1% low-melting-point agarose, trimmed, and mounted on stubs, then dehydrated in methanol and cleared in benzyl alcohol:benzyl benzoate (1:2). Cleared specimens in benzyl alcohol:benzyl benzoate solution were then imaged under white light (to detect X-gal staining) and ultraviolet light (for anatomic detail), consecutively, using a Bioptonics 3001M Optical Projection Tomography scanner and raw data processed using the NRecon Version 1.6.2 reconstruction software (Skyscan). The image dataset acquired using white light was then processed using CTan software (Version 1.10; Skyscan) to manually segment out staining within the heart and umbilical arteries as separate datasets. All 4 volumes were concurrently rendered in the Drishti, Version 2.0 Volume Exploration software (developed by Ajay Limaye, Australian National University Supercomputer Facility). Movie files were either generated directly using Drishti or postprocessed from image stacks using Quicktime Pro, Version 7.6.6 or iMovie, Version 8.0.6 (Apple Inc).

Results

The vitelline artery undergoes extensive remodeling during embryogenesis

The VE-cad Cre recombinase mouse line fate maps the vasculature and subsequent hematopoietic progenitors (HPs) that arise from hemogenic endothelium.21 Thus, when crossed to a R26R LacZ Cre-reporter line,32 the dorsal aorta of the AGM as well as its hematopoietic-derived cells can be traced by β-galactosidase staining (Figure 1A). Similar to the dorsal aorta, the vitelline artery, which has been shown to have hematopoietic activity,27,34 is also labeled and exhibits large clusters of endothelial-derived HCs (Figure 1B). Indeed, the vitelline artery appears to be more robust than the dorsal aorta in both the size and the frequency of the clusters observed by E10.0 to E11.0.

The vitelline artery (VA) undergoes extensive remodeling during embryonic development. (A) The VE-cadherin Cre mouse line, crossed to a R26R Cre reporter (lacZ in blue), exhibits vascular and hematopoietic labeling in the AGM at E11.0 (left) and in the VA at E10.5 (right, arrows). (B) The VA at E10.25 connects to the dorsal aorta via multiple smaller vessels that run along the midgut loop (mgl). The vitelline vein (VV) runs directly to the fetal liver (Lv). Orthogonal planes of section demonstrate hematopoietic clusters in the main arterial segment (top right) and in the tributaries associated with the midgut (mg, bottom right). (C) The remodeling of the VA (also called the omphalomesenteric artery [OA]) can be followed in embryo dissections from E9.0 to E11.0. The VA is initially connected to the umbilical arteries (UA) at E9.0. The UA connection is later eliminated on the establishment of a new connection to the dorsal aorta (DA). Subsequent to the dissolution of the UA connection, large clusters of cells are noted (arrows). (D) The remodeling events are shown in this schema. On vascular remodeling of the VA, large clusters of cells are collected in the regressing vessel within close proximity to the midgut loop. (E) Optical projection tomography scans of an embryo at E10.5 demonstrate the VA remodeling events in 3 dimensions, where the VA and yolk sac are highlighted in red, the heart and umbilical vessels are in yellow, and the regressing part of the VA and clusters noted by arrowheads. (A-C) Scale bars as labeled per row.

The vitelline artery (VA) undergoes extensive remodeling during embryonic development. (A) The VE-cadherin Cre mouse line, crossed to a R26R Cre reporter (lacZ in blue), exhibits vascular and hematopoietic labeling in the AGM at E11.0 (left) and in the VA at E10.5 (right, arrows). (B) The VA at E10.25 connects to the dorsal aorta via multiple smaller vessels that run along the midgut loop (mgl). The vitelline vein (VV) runs directly to the fetal liver (Lv). Orthogonal planes of section demonstrate hematopoietic clusters in the main arterial segment (top right) and in the tributaries associated with the midgut (mg, bottom right). (C) The remodeling of the VA (also called the omphalomesenteric artery [OA]) can be followed in embryo dissections from E9.0 to E11.0. The VA is initially connected to the umbilical arteries (UA) at E9.0. The UA connection is later eliminated on the establishment of a new connection to the dorsal aorta (DA). Subsequent to the dissolution of the UA connection, large clusters of cells are noted (arrows). (D) The remodeling events are shown in this schema. On vascular remodeling of the VA, large clusters of cells are collected in the regressing vessel within close proximity to the midgut loop. (E) Optical projection tomography scans of an embryo at E10.5 demonstrate the VA remodeling events in 3 dimensions, where the VA and yolk sac are highlighted in red, the heart and umbilical vessels are in yellow, and the regressing part of the VA and clusters noted by arrowheads. (A-C) Scale bars as labeled per row.

In the embryo, the vitelline artery is a temporary structure that traverses a path toward the aorta in midgestation where it runs along the midgut mesentery, regresses to a large extent, remodels, and eventually contributes to the superior mesenteric artery.37 As a result of its proximity to the midgut, morphologic analyses provide various perspectives of hematopoietic emergence from the vitelline artery. Whereas transverse sections of the artery before its integration into the midgut mesentery demonstrate single large clusters of labeled HCs, sections along the midgut depict multiple vascular structures filled with large hematopoietic clusters (Figure 1B). The latter very closely resemble the previously described mesenteric blood islands.28

When the vitelline artery is evaluated via vascular lineage tracing, the various stages of vascular remodeling can be easily followed and studied (Figure 1C). At E9.0, the vitelline artery (also known as the omphalomesenteric artery) is directly connected to both umbilical arteries.28,37 This initial connection is lost over time as the vitelline artery establishes a new connection to the dorsal aorta.28,37 The link to the dorsal aorta occurs initially via a delta of multiple tributaries that are remodeled onto a single vessel by E11.0 (Figure 1C-D). A product of this remodeling is the emergence of large endothelial-derived cell clusters (Figure 1D-E arrows) that are located in the caudal aspect of the midgut at E10.5 (Figure 1C-E). Rapidly thereafter (by E11.0), HC clusters are intermittently found on the cranial aspect of midgut proximal to the fetal liver (Figures 1C-D, 2A). This rapid change in location could not be accomplished solely through cell migration. A likely possibility is that the relocation of these clusters is in large part the product of midgut rotation (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), as these blood islands are directly associated with the mesenteric tissues in which the midgut is incorporated. These remodeling events have been observed in all embryos evaluated (Table 1) and across mouse lines (Table 2).

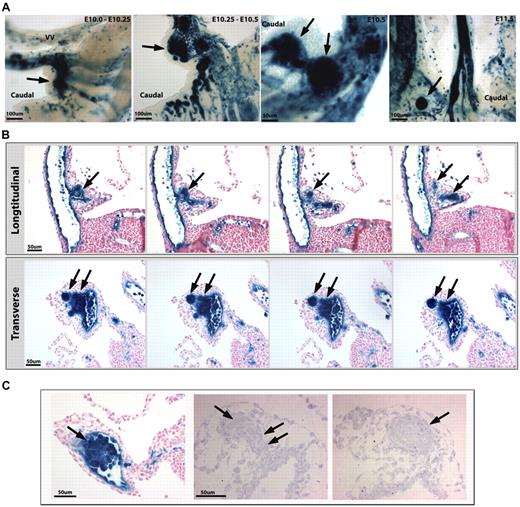

VA cell clusters become extraluminal. (A) VE-cadherin Cre mouse line, crossed to a R26R Cre reporter (β-galactosidase in blue), demonstrates large cell clusters from E10.0 to E10.5 that appear to migrate out of the vessel by E10.75 to E11.0 (arrows) on the caudal side of the artery. By E11.5, smaller clusters are noted on the opposite (cranial) side and proximal to the fetal liver. (B) Serial longitudinal (top) and transverse (bottom) sections through the VA at E10.25 to E10.5 show extravascular budding of the hematopoietic clusters (arrows). (C) The VA produces large clusters of HCs as traced by the VE-cadherin Cre line (β-galactosidase in blue, left panel). Semithin sections (right panels) show clusters of round cells budding from the artery (note the connection of the cluster with the VA; double arrows). A subsequent serial section (to the right) shows a cluster of cells surrounded by an endothelial layer resembling previously described mesenteric blood islands (arrow). (A-C) Scale bars as labeled per row.

VA cell clusters become extraluminal. (A) VE-cadherin Cre mouse line, crossed to a R26R Cre reporter (β-galactosidase in blue), demonstrates large cell clusters from E10.0 to E10.5 that appear to migrate out of the vessel by E10.75 to E11.0 (arrows) on the caudal side of the artery. By E11.5, smaller clusters are noted on the opposite (cranial) side and proximal to the fetal liver. (B) Serial longitudinal (top) and transverse (bottom) sections through the VA at E10.25 to E10.5 show extravascular budding of the hematopoietic clusters (arrows). (C) The VA produces large clusters of HCs as traced by the VE-cadherin Cre line (β-galactosidase in blue, left panel). Semithin sections (right panels) show clusters of round cells budding from the artery (note the connection of the cluster with the VA; double arrows). A subsequent serial section (to the right) shows a cluster of cells surrounded by an endothelial layer resembling previously described mesenteric blood islands (arrow). (A-C) Scale bars as labeled per row.

The vascular remodeling events result in the formation of endothelial-derived extravascular hematopoietic clusters

The formation of large hematopoietic clusters within a vessel that is regressing from a former vascular connection suggests that HPs do not require circulation or even a functional lumen. Longitudinal and transverse sections of hematopoietic emergence from the vitelline artery indicate that the HCs exit the main vascular lumen almost en mass (Figure 2B). Furthermore, semithin sections of the areas (Figure 2C) demonstrate the maintenance of an endothelial layer, giving the true appearance of a blood island, similar to those found in the early yolk sac.28 In addition, electron microscopy analyses demonstrate the intimate association between the ECs and HCs within the blood islands (Figure 3A). In some cases, these 2 cells share the same cytoplasm at their interface (Figure 3B), suggesting that perhaps HCs “bud” from ECs. Using the VE-cad Cre line crossed to an EYFP Cre reporter, explant cultures showed the continued vascular remodeling of the vitelline artery in lieu of circulation, suggesting that the HP clusters can form and migrate without circulatory flow (supplemental Figure 2).

ECs and HCs have cytoplasmic continuity in the VA. (A) Electron microscopy of 2 independent VA clusters at lower (left panels) and higher magnification (right panels) revealed close EC and HC interactions (top and bottom panels). Certain areas of EC-HC contact appear devoid of any cytoplasmic boundaries (arrows). In addition, the HCs are in a proliferative state, as suggested by the condensed chromatin and mitotic appearance of the nuclei (asterisks). (B) Higher magnification demonstrates the loss of boundaries in EC-HC associations of the VA (arrows, left 2 panels). N indicates the nucleus of the EC. We also found cases where intact boundaries were also noted (arrowheads, rightmost panel).

ECs and HCs have cytoplasmic continuity in the VA. (A) Electron microscopy of 2 independent VA clusters at lower (left panels) and higher magnification (right panels) revealed close EC and HC interactions (top and bottom panels). Certain areas of EC-HC contact appear devoid of any cytoplasmic boundaries (arrows). In addition, the HCs are in a proliferative state, as suggested by the condensed chromatin and mitotic appearance of the nuclei (asterisks). (B) Higher magnification demonstrates the loss of boundaries in EC-HC associations of the VA (arrows, left 2 panels). N indicates the nucleus of the EC. We also found cases where intact boundaries were also noted (arrowheads, rightmost panel).

The hematopoietic clusters are viable and exhibit hemogenic endothelial and HSC markers

A possible consequence of large hematopoietic clusters collecting in a regressing vessel could be cell death with no functional significance. To investigate this possibility, apoptosis was evaluated and noted to be absent within the hematopoietic clusters (Figure 4A). In addition, a marker of cell proliferation phospho-histone H3, labeled cells within the hematopoietic clusters (Figure 4A), indicating that the HCs making up the cell clusters are viable and proliferative.

VA-derived cell clusters are viable and express hematopoietic markers. (A) VE-cadherin Cre fate mapped endothelial and HCs in green (crossed to a R26R EYFP Cre reporter) were costained with proliferation marker phospho-histone H3 (pH3, top panel in red) and apoptosis marker cleaved caspase-3 (bottom panel in red). Some proliferation within the cell clusters is noted (arrows, top panel), although no apoptosis is detected. There is one cell outside of the cluster found to be positive for caspase-3 (arrows). (B) CD41 (top panel in red), a marker of HSCs and hemogenic endothelium, is expressed within EYFP+ cell clusters (arrows) and in circulating HCs in an adjacent vessel (arrowheads). Ikaros (bottom panel in red), a gene expressed by HSCs and lymphoid progenitors, exhibits a similar expression pattern (arrows and arrowheads). (C) The Runx1-LacZ knock-in mouse line exhibits early Runx-1 (blue) endothelial expression within the VA (arrows, left panels), and later within the artery associated cell clusters (arrows, right panels). (A-C) Scale bars as labeled per row.

VA-derived cell clusters are viable and express hematopoietic markers. (A) VE-cadherin Cre fate mapped endothelial and HCs in green (crossed to a R26R EYFP Cre reporter) were costained with proliferation marker phospho-histone H3 (pH3, top panel in red) and apoptosis marker cleaved caspase-3 (bottom panel in red). Some proliferation within the cell clusters is noted (arrows, top panel), although no apoptosis is detected. There is one cell outside of the cluster found to be positive for caspase-3 (arrows). (B) CD41 (top panel in red), a marker of HSCs and hemogenic endothelium, is expressed within EYFP+ cell clusters (arrows) and in circulating HCs in an adjacent vessel (arrowheads). Ikaros (bottom panel in red), a gene expressed by HSCs and lymphoid progenitors, exhibits a similar expression pattern (arrows and arrowheads). (C) The Runx1-LacZ knock-in mouse line exhibits early Runx-1 (blue) endothelial expression within the VA (arrows, left panels), and later within the artery associated cell clusters (arrows, right panels). (A-C) Scale bars as labeled per row.

To determine whether the cells composing the clusters were indeed HCs, we evaluated CD41+, a marker of hemogenic endothelium and nascent endothelial-derived blood,9,10,19,20 as well as Ikaros, a gene expressed in HSC progenitors and lymphoid precursors.38 The vitelline artery derived HP clusters expressed both CD41 and Ikaros (Figure 4B). Runx-1, a transcription factor critical to definitive hematopoiesis,27,39 and more recently found to be required for endothelial to hematopoietic transition,10,17 was also investigated using the Runx-1 LacZ knock-in mouse line. The vitelline arterial endothelium exhibits Runx-1 expression very early on, with later expression in the vitelline artery–derived hematopoietic clusters (Figure 4C), providing further support that the hematopoietic clusters (mesenteric blood islands) are composed of hematopoietic progenitors.

Vitelline artery–derived HCs are functional and resemble the fetal liver hematopoietic population

To evaluate hematopoietic function within the vitelline artery and its hematopoietic derivatives, the vitelline artery (from the yolk sac to its connection with the midgut) was dissected and its functional capacity was compared with that of the fetal liver during the same time points (between E10 and E11). The vitelline artery was capable of forming various hematopoietic colonies (Figure 5A), with total colony number approximating that of the fetal liver (Figure 5B) during the time period where the extravascular clusters are noted (E10-E10.5). When the clusters began to dissipate by late E10 to E11, the colony-forming capacity was maintained by the vitelline artery but was far surpassed by the fetal liver at this time point (Figure 5B). When colony type was evaluated, there were no major differences in number of erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-e), macrophage (Mac), or mixed colonies of granulocyte/macrophage with or without erythroid (Mix) during the peak in hematopoietic cluster emergence (E10-E10.5). By late E10 to E11, however, the BFU-e capacity of the vitelline artery was exhausted and Mac/Mixed colony numbers began to decline compared with the fetal liver (Figure 5B).

VA-associated HCs are functional. (A) Dissected VAs were cultured in methylcellulose and formed distinct colonies of BFU-e, Mac, and mixed colonies of granulocyte/macrophage with or without erythroid (Mix). (Top panels) Colony morphology. (Bottom panels) Cytospins of each colony type after Giemsa stain (purple). Scale bars as labeled per row. (B) Colony formation ability of the VA (in purple) is compared with the fetal liver (FL, in blue) during VA remodeling. A peak in VA colony activity is seen at E10 to E10.5 corresponding to the major vascular remodeling events, and is comparable with the fetal liver at this time point. By E10.5 to E11, the ability of the VA to form hematopoietic colonies is dramatically reduced. Error bars are average of triplicate cultures of n = 2 litters (each litter pooled separately per time point ± SEM). (C) VAs and fetal livers (FL) of VE-cadherin Cre crossed to R26R LacZ lines at E10.5 were collected (pooled together in single suspension, 1 litter each) and evaluated by FACS analysis for LacZ activity (FDG, left panel). Endothelial derived (FDG+) cells make up 60% of the collected cells, and within that population the stem cell markers c-kit and CD34 are highly expressed (right panel, percentage labeled per quadrant). The VA hematopoietic population surface marker expression very closely resembles the FL at this time point.

VA-associated HCs are functional. (A) Dissected VAs were cultured in methylcellulose and formed distinct colonies of BFU-e, Mac, and mixed colonies of granulocyte/macrophage with or without erythroid (Mix). (Top panels) Colony morphology. (Bottom panels) Cytospins of each colony type after Giemsa stain (purple). Scale bars as labeled per row. (B) Colony formation ability of the VA (in purple) is compared with the fetal liver (FL, in blue) during VA remodeling. A peak in VA colony activity is seen at E10 to E10.5 corresponding to the major vascular remodeling events, and is comparable with the fetal liver at this time point. By E10.5 to E11, the ability of the VA to form hematopoietic colonies is dramatically reduced. Error bars are average of triplicate cultures of n = 2 litters (each litter pooled separately per time point ± SEM). (C) VAs and fetal livers (FL) of VE-cadherin Cre crossed to R26R LacZ lines at E10.5 were collected (pooled together in single suspension, 1 litter each) and evaluated by FACS analysis for LacZ activity (FDG, left panel). Endothelial derived (FDG+) cells make up 60% of the collected cells, and within that population the stem cell markers c-kit and CD34 are highly expressed (right panel, percentage labeled per quadrant). The VA hematopoietic population surface marker expression very closely resembles the FL at this time point.

Analysis of HSC markers within the VE-cadherin Cre R26R LacZ Cre reporter line by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) demonstrated cell populations expressing c-kit+ and CD34+ within the LacZ (FDG)-labeled population (Figure 5C). Comparable levels of these markers were seen in the vitelline artery and fetal liver populations at this time point (E10.5). The ckit+ CD34+ phenotype was previously noted to be an early marker of murine HSCs,29,40 and all 3 ckit+, CD34+, and ckit+CD34+ double-positive populations were enriched within the FDG fraction (data not shown).

Tracing lateral plate mesoderm demonstrates that all hemogenic endothelial beds, including the vitelline artery and its derivatives, share the same mesodermal origin

Vascular beds capable of hematopoietic emergence during development appear to differ from other vascular beds in their mesodermal origins.21 To further investigate this, we evaluated a HoxB6 Cre mouse line (crossed to a R26R LacZ Cre reporter line) that uses the lateral plate enhancer element of the HoxB6 promoter to lineage trace lateral plate mesoderm (LPM).31 Using this line, it was previously shown that LPM populations contribute to the vascular endothelium of the aorta but have minimal contribution to vascular smooth muscle cells with the exception of the lower abdominal aorta.41 When the various vascular beds known to harbor hemogenic endothelium were investigated, the LPM populations universally gave rise to the endothelium composing hemogenic vascular sites: the AGM, yolk sac, and placenta (Figure 6A). When the vitelline artery–derived hematopoietic clusters were investigated, they are also traced from LPM, as was the surrounding mesenteric mesenchyme (Figure 6B).

Lateral plate mesoderm contributes to hemogenic endothelial beds, including the VA and its hematopoietic derivatives. (A) The HoxB6 Cre mouse line was crossed to a R26R LacZ Cre reporter mouse to lineage-trace LPM. All previously reported hemogenic endothelial beds, including the AGM at E11 (top panel), yolk sac (middle panel), and placenta (bottom panel) (both at E10.5), were faithfully labeled (β-galactosidase in blue) from labeled LPM. The associated HCs were also labeled, except for the yolk sac where labeled (arrow) and unlabeled (arrowhead) HCs are seen. (B) The VA-derived hematopoietic clusters (HC, arrows) and all the surrounding endothelium and mesoderm are traced from the LPM at E10.5. (C) The adult bone marrow (BM) in the HoxB6-Cre mouse is fully labeled, indicating an LPM origin (histologic LacZ section on left). FACS analyses using a EYFP reporter (graph on right) demonstrates that EYFP+ cells constitute 98% of CD45+ BM cells and that the majority of all hematopoietic lineages are also EYFP+ and thus have an LPM origin. Graphical results are shown as the mean (n = 3) ± SEM (A-C) Scale bars as labeled.

Lateral plate mesoderm contributes to hemogenic endothelial beds, including the VA and its hematopoietic derivatives. (A) The HoxB6 Cre mouse line was crossed to a R26R LacZ Cre reporter mouse to lineage-trace LPM. All previously reported hemogenic endothelial beds, including the AGM at E11 (top panel), yolk sac (middle panel), and placenta (bottom panel) (both at E10.5), were faithfully labeled (β-galactosidase in blue) from labeled LPM. The associated HCs were also labeled, except for the yolk sac where labeled (arrow) and unlabeled (arrowhead) HCs are seen. (B) The VA-derived hematopoietic clusters (HC, arrows) and all the surrounding endothelium and mesoderm are traced from the LPM at E10.5. (C) The adult bone marrow (BM) in the HoxB6-Cre mouse is fully labeled, indicating an LPM origin (histologic LacZ section on left). FACS analyses using a EYFP reporter (graph on right) demonstrates that EYFP+ cells constitute 98% of CD45+ BM cells and that the majority of all hematopoietic lineages are also EYFP+ and thus have an LPM origin. Graphical results are shown as the mean (n = 3) ± SEM (A-C) Scale bars as labeled.

Universally, the endothelial-associated HCs from these vascular sites were traced from LPM, with one exception: the yolk sac (Figure 6A). This pattern also resembles the yolk sac labeling in the VE-cad Cre mouse line,30 suggesting that a subset of early HCs are not traced within these Cre lineages. However, unlike the VE-cad Cre line, when the adult bone marrow (a measure of definitive HSC capacity) is evaluated in the HoxB6 Cre, the entire (98%) adult bone marrow population is labeled, with representation of all lineages (Figure 6C). Thus, LPM-derived endothelial populations do give rise to definitive hematopoiesis, and the unlabeled yolk sac cells could represent a primitive hematopoietic population that does not maintain itself in the adult bone marrow. In addition, the vitelline arterial hematopoietic clusters (previously reported mesenteric blood islands) are derived from hemogenic endothelium and share the same LPM origins as other hemogenic vascular beds.

It should be stressed that the HoxB6 Cre did not exclusively label hemogenic vascular beds as some intersomitic vessels were also labeled (supplemental Figure 3A). However, no previously reported hemogenic endothelial site was found to be unlabeled. Interestingly, the vasculature of the fetal liver at E14.5 was not labeled (supplemental Figure 3A), correlating with previous data that the fetal liver endothelium does not possess hematopoietic capacity.21 Aside from the aortic endothelium and its branches (supplemental Figure 3B), only a few small splenic ECs were traced (supplemental Figure 3C), which may correspond to embryonic labeling of the vitelline artery and its contribution to mesenteric vessels in that region. When the adult hematopoietic organs were evaluated, the hematopoietic populations of the bone marrow, thymus, and spleen were overwhelmingly labeled (supplemental Figure 3C).

Discussion

The identification of hemogenic endothelium imparts tremendous potential for therapeutic applications of HSC production in vitro. However, before clinical applications can be pursued, it is imperative to understand the nature of the endothelium with hemogenic capability, and which vascular sites contain hemogenic endothelium. Through lineage tracing, we have identified the source of mesenteric blood islands: the vitelline artery, a site of hemogenic endothelium. But unlike previously described hemogenic vascular beds, hematopoietic emergence from the vitelline artery follows a set of events that results in extravascular segregation of hematopoietic clusters and their possible extracirculatory migration to the fetal liver. This is in stark contrast to the initial paradigm where HCs bud from the endothelium to enter the circulation and also suggests that circulation may be dispensable for hematopoietic emergence, which recent in vitro data may support.9,10,20 However, circulation has been shown to be critical for HSC production in the zebrafish embryo,42 and augments HSC emergence in culture.43 Yet, these studies focus on dorsal aortic HSC emergence, and it may be that the vitelline arterial HSC emergence is less susceptible to circulatory flow because of its unique remodeling events and HC cluster formation.

The vitelline artery derivatives (mesenteric blood islands) are probably the same structures previously identified in the subaortic AGM mesoderm16,22 that aided in the confusion of whether aortic HSCs were endothelial or mesodermal derived. We now show that these “para-aortic foci”22 in the mesentery are derived from the vitelline artery and may migrate to the fetal liver in lieu of circulation. In addition, we have demonstrated that the mesenteric blood islands are indeed composed of endothelial-derived functional hematopoietic progenitors (and probably HSCs, although direct transplantation of specific HC clusters is not feasible), which is not surprising as the vitelline artery has been shown to have long-term HSC activity.27,34 The vitelline artery is also known to produce hematopoietic clusters that bud into a large lumen much like the dorsal aorta and other vascular beds.15 We observed this as well but also demonstrate an alternative mechanism of hematopoietic emergence and/or migration that occurs in the remodeled branches of the vitelline artery.

Using genetic cell tracing, we have been able to identify the lateral plate mesoderm as the exclusive source of hemogenic endothelium in the mouse. Although there exist small populations of nonhemogenic vascular beds traced from LPM, the fact that all hemogenic vascular beds are of LPM origin suggests that the endothelial capacity to produce blood may be predicated on developmental origin. Avian data have long demonstrated that vascular beds are composed of both somitic and lateral plate mesodermal derivatives, the latter contributing to the hemogenic aortic floor.44,45 This is of critical importance to dissecting the processes responsible for endothelial-derived HSCs, as it may be that only LPM-derived vascular beds can ever be reprogrammed to produce HSCs in vitro. In addition, it may be revealing to understand how these LPM-derived vascular beds differ from nonhemogenic beds in their development and maintenance. One interesting observation is that, aside from the dorsal aorta, almost all the other hemogenic vascular sites are obliterated or remodeled before or on parturition, thus leaving the aorta as the sole remaining adult endothelium once capable of HSC production.

Yet, the aortic process of endothelial hematopoiesis has recently been shown to be closer to transdifferentiation than to mother-daughter cell division.18,19 At least in the zebrafish, the endothelium of the dorsal aorta during the hematopoietic process results in the rolling up and delamination of ECs from the aortic wall to enter the circulation as blood cells, as 2 papers have elegantly shown in vivo,18,19 thus leaving the adult animal devoid of any true hemogenic endothelium. However, it appears that the shared LPM origin of hemogenic endothelium does not preclude mechanistic diversity between the hemogenic vascular beds. We present data here that describe a novel process of endothelial hematopoietic emergence through vascular remodeling of the vitelline artery. In addition, we also observe the absence of cytoplasmic borders between ECs and HCs in this region, which may suggest an alternate mechanism to the EC-HC transition seen in zebrafish. It may be that, although a common developmental origin may uniformly provide a permissive environment for hemogenic endothelium, each vascular bed may use different mechanisms to achieve the same end: hematopoiesis. Ideally, fate tracing of each hemogenic vascular bed separately but in vivo will allow further insight and refinement of the various mechanisms endothelia use to produce HSCs. Hemogenic capacity is known to be exclusive to arteries,46 and specifically arteries of LPM origin, but unfortunately that is not enough to distinguish each hemogenic vascular bed separately. Until we can dissect molecular signatures integral and unique to each hemogenic vascular bed, we cannot yet fate map each exclusive contribution to HSCs or unlock the possible therapeutic potential of each.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Steven Smale and Carrie Miceli and members of their respective laboratories for use of their FACSCalibur flow cytometers, Liman Zhao for assistance with animal husbandry, the Tissue Procurement Core Laboratory Shared Resource at the University of California at Los Angeles, and the Small Animal Tomographic Analysis Facility at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA), where the optical projection tomography scanning of X-gal–stained embryos was performed.

This work was supported by California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Fellowship and Burroughs Wellcome Career Award for Medical Scientists (A.C.Z.) and California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Award (RB1-01328; M.L.I.-A.).

Wellcome Trust

Authorship

Contribution: A.C.Z., J.C.G., and M.L.I.-A. designed the research; A.C.Z., K.A.T., R.M.P., M.R.L., K.C.C., and J.J.H. performed the research; A.C.Z., K.A.T., R.M.P., M.L.I.-A., M.R.L., J.C.G., and T.C.C. analyzed data; and A.C.Z. and M.L.I.-A. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: M. Luisa Iruela-Arispe, Molecular Biology Institute, University of California at Los Angeles, 615 Charles E. Young Dr South, Los Angeles, CA 90095; e-mail: arispe@mcdb.ucla.edu.

![Figure 1. The vitelline artery (VA) undergoes extensive remodeling during embryonic development. (A) The VE-cadherin Cre mouse line, crossed to a R26R Cre reporter (lacZ in blue), exhibits vascular and hematopoietic labeling in the AGM at E11.0 (left) and in the VA at E10.5 (right, arrows). (B) The VA at E10.25 connects to the dorsal aorta via multiple smaller vessels that run along the midgut loop (mgl). The vitelline vein (VV) runs directly to the fetal liver (Lv). Orthogonal planes of section demonstrate hematopoietic clusters in the main arterial segment (top right) and in the tributaries associated with the midgut (mg, bottom right). (C) The remodeling of the VA (also called the omphalomesenteric artery [OA]) can be followed in embryo dissections from E9.0 to E11.0. The VA is initially connected to the umbilical arteries (UA) at E9.0. The UA connection is later eliminated on the establishment of a new connection to the dorsal aorta (DA). Subsequent to the dissolution of the UA connection, large clusters of cells are noted (arrows). (D) The remodeling events are shown in this schema. On vascular remodeling of the VA, large clusters of cells are collected in the regressing vessel within close proximity to the midgut loop. (E) Optical projection tomography scans of an embryo at E10.5 demonstrate the VA remodeling events in 3 dimensions, where the VA and yolk sac are highlighted in red, the heart and umbilical vessels are in yellow, and the regressing part of the VA and clusters noted by arrowheads. (A-C) Scale bars as labeled per row.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/116/18/10.1182_blood-2010-04-279497/4/m_zh89991060430001.jpeg?Expires=1765951977&Signature=ZK~bcXVVucOfllY0AplHIj1d~Gz9DK2xbT~kChaGrmzkNmA4w~ZZaZoAHNx08DXp~Y9prVXzsJgUM8ltWEEnZfQz2ZMV1zt3zpZttfhlvzaOwzCu2e1NjSUONwst~Lv0JGKV-iUHBiL2ajPIFsmlrQ9y9S0bZS-qFZ8auclhRoBufPpYLwD2MBVy0wlmicJzAPfK-~MRb6tiL0ecfGQohgOpFkBdBaMOFGKNqyw-lkf872qnXxCQ~8MT5yDrhFl43DbkexaOWAqbjDRO7Fp~SUpqJOriNg5b0qagceR4GTqEbbQ5qrK0XxdmLVNBCWv753yWeetyMyrfdwf9cNQLWw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)