P-gp (also termed MDR1, or multidrug resistance-1) is a member of the membrane ATP cassette family that mediates efflux of several drugs commonly used to treat AML. Its expression has been correlated with an adverse outcome,1 which was thought to occur because it mediates resistance to chemotherapy.

Inhibiting P-glycoprotein (P-gp) has been long hypothesized as a mechanism for improving acute myeloid leukemia (AML) outcome, especially in the elderly who have markedly decreased remission and survival rates compared with younger patients.1 SWOG 9126 found a benefit for event-free, but not overall, survival of P-gp inhibition with cyclosporine in AML induction.2 However, 3 subsequent randomized trials using either cyclosporine or PSC-833 to inhibit P-gp were not able to replicate the benefit seen in the previous SWOG study for event-free survival.3-7 Thus, whether P-gp inhibition might improve AML outcomes has been controversial. One important question in this area not yet answered was whether P-gp inhibition could specifically enhance remission rates and subsequent survival in elderly patients (> 65 years) who have increased P-gp levels on their leukemia cell population compared with younger patients. The clinical trial (E3999) reported by Cripe et al in this issue of Blood addresses this exact question: can inhibiting P-gp improve outcome in elderly AML? Unfortunately, this well-designed and well-conducted trial did not show any benefit from inhibition of P-gp.8

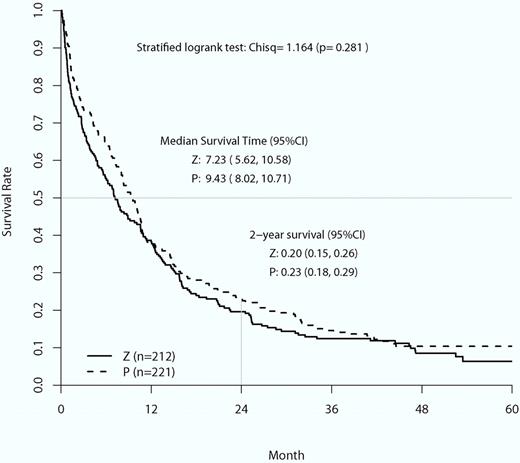

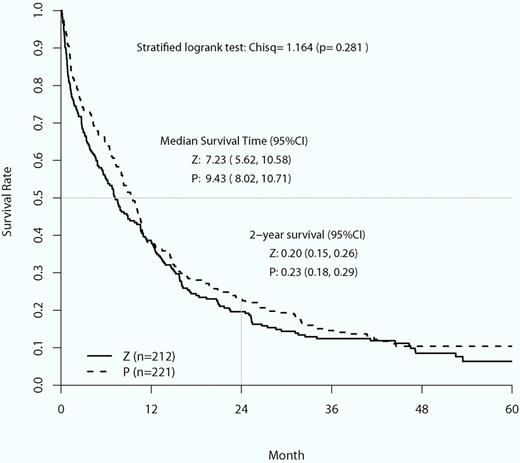

Overall survival curves of the placebo control (P) group compared with the zosuquidar infusion group (Z). Stratified log-rank χ2 analysis found no statistical difference in mean overall survival or 2-year survival between the 2 groups (image is Figure 2 from Cripe et al8 ).

Overall survival curves of the placebo control (P) group compared with the zosuquidar infusion group (Z). Stratified log-rank χ2 analysis found no statistical difference in mean overall survival or 2-year survival between the 2 groups (image is Figure 2 from Cripe et al8 ).

This trial tested whether the infusion of zosuquidar, a potent and well-tolerated P-gp inhibitor, during induction with cytarabine for 7 days and daunorubicin for 3 days improved remission rates, duration, and overall survival. The trial had reasonable power, accrued well, was randomized and placebo controlled, and had appropriate end points. The expression of P-gp between the placebo and zosuquidar groups was equivalent. The serum concentra-tions of daunorubicinol were greater in the patients receiving zosuquidar compared with those who were not, indicating that zosuquidar did achieve its desired pharmacokinetic affect. These measurements forestalled the criticism that no benefit was found because drug efflux was not appropriately inhibited. There was no difference in all-cause mortality between the 2 groups, indicating that zosuquidar was not toxic. However, it did not have any benefit in preventing relapse or improving overall survival.

Although P-gp is perhaps the major mediator of leukemia drug efflux, other membrane proteins have also been implicated in this phenomenon, including MRP, LRP, and BRCP. In E3999, these efflux proteins were indeed expressed by leukemia cells in the majority of patients. However, there was no direct correlation between overall survival and the percentage of leukemia cells expressing any of these efflux proteins, or with the intensity of staining for these efflux proteins. This addresses the possibility that there was no benefit from zosuquidar because it targeted the wrong efflux protein. These data imply that the increased expression of P-gp in poor-prognosis AML is probably not the cause of the poor prognosis, but the result.

This carefully performed study lays to rest the concept that inhibition of ATP cassette drug efflux can improve outcome in AML. Thus, further efforts in this area should be rapidly redirected to other potential treatment options. It is discouraging that zosuquidar did not have any benefit, as elderly AML is indeed an area that dearly needs better therapy. Nonetheless, the value of this study is that it will allow resources to be directed elsewhere. Thus, although this is a negative study, it is still important, in that it has been done care-fully, and therefore should settle this hotly debated question of whether drug efflux inhibitors can improve outcome in AML.

Resources for clinical trials are finite, and closing the door on controversial questions may be as important as positive results. Investigators all too often ask the same question in slightly different ways. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has recently called for dramatic changes in the conduct and funding of National Cancer Institute studies.9 One of the key recommendations of this report is to focus on innovation in clinical trials. This implies the need to move on to alternative strategies when a well-designed trial shows a negative result, such as here. One potential solution to this issue may be found in the IOM recommendation that “only well-designed clinical trials that have the greatest possibility of improving survival and quality of life for cancer patients are undertaken.” Native American tribal wisdom says that when you discover you are riding a dead horse, the best strategy is to dismount. Based on a large amount of animal work, and an initial positive clinical trial, P-gp inhibition held significant promise to improve survival in AML, especially in the elderly. However, based on the findings of this study, combined with the previous trials, further clinical trials in this area should be viewed with skepticism, and effort redirected to other, more novel, strategies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■