HIV-associated plasmablastic multicentric Castleman disease is an increasingly frequent diagnosis. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus is found in the monotypic polyclonal plasmablasts that characterize this disease. Unlike Kaposi sarcoma, the incidence does not correlate with CD4 cell count or use of highly active antiretroviral therapy. It is a relapsing and remitting illness, and diagnostic criteria are emerging that define disease activity based on the presence of a fever and raised C-reactive protein coupled with a list of clinical features. Treatment protocols increasingly stratify therapy according to performance status and organ involvement. I advocate rituximab monotherapy for good performance status patients without organ involvement and rituximab with chemotherapy for more aggressive disease. The success of antiherpesvirus agents in controlling active disease is limited, but valganciclovir may have a role as maintenance therapy in the future.

Introduction

Benjamin Castleman originally described his eponymous disease in 1954.1 Most of the patients he identified had asymptomatic localized mediastinal lymphadenopathy with follicular hyperplasia and capillary hyalinization.2 During the 1960s, a new variant of Castleman disease was described that lacked hyalinization, had concentric sheets of plasma cells both surrounding the germinal centers and in the interfollicular space. It was associated with systemic manifestations3 and became known as plasma cell variant of Castleman disease. More recently, a third subtype has been identified known as plasmablastic multicentric Castleman disease (MCD), which is multifocal, behaves more aggressively, and was first described in association with POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes) or Crow-Fukase disease. In this variety, the mantle zones of involved nodes contain large abnormal plasma cells with prominent nucleoli and copious cytoplasm that have been named plasmablasts.4,5 It is this form of plasmablastic MCD that is found with increased frequency in persons living with HIV infection,6 and HIV-associated MCD (HIV MCD) is the focus of this review.

Although MCD occurs with a vastly increased incidence in people living with HIV infection, epidemiologic studies have demonstrated no correlation with CD4 cell count or the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).6 Indeed, a systematic review of all 72 cases of HIV MCD published up to 2007 found that 64% of the 48 patients diagnosed with MCD in the HAART era were already on HAART at the time of MCD diagnosis.7 Moreover, there is also no correlation between the risk of relapse of HIV MCD and CD4 cell count.8,,,–12 In these respects, MCD resembles a number of non–AIDS-defining malignancies and, like them, the incidence of HIV MCD is not declining and has been reported to be rising, although case identification bias may also play a role.6

A link between MCD and Kaposi sarcoma (KS) was found in a number of early case reports, and the 2 diseases coexisted in 72% of HIV MCD patients in the systematic review7 and 54% of 56 patients at Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, London (Table 1). In addition, biopsy specimens frequently demonstrate both diseases in the same lymph node.13 After the identification of KS herpesvirus (KSHV), which is also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), this virus was found to be present in the plasmablasts in all cases of HIV MCD.14,15 Furthermore, high levels of KSHV DNA may be quantified in peripheral blood mononuclear cells or plasma in patients with symptomatic active HIV MCD.8,9,11,16,–18

Diagnosis and investigations

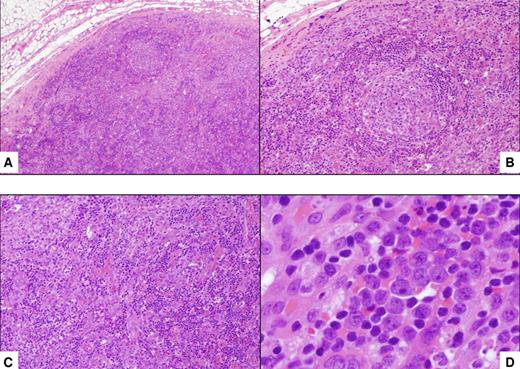

The diagnosis of HIV MCD is based on the presence of histopathologic features; however, because of the remitting and relapsing nature of MCD, clinical correlates should also be present to confirm a diagnosis of active disease.19 The diagnosis can only be established with histologic confirmation, and this should be aggressively pursued in patients with clinical findings in keeping with HIV MCD. The histologic characteristics of plasmablastic MCD include the presence of plasmablasts within the mantle zone of B-cell follicles, and immunohistochemical staining reveals KSHV-associated latent nuclear antigen-1 in these cells5,20 (Figures 1–2). The plasmablasts express high levels of cytoplasmic immunoglobulin, that is always IgMλ restricted.5,21 Despite the expression of monotypic IgMλ, the plasmablasts have polyclonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangements21 and the KSHV episomes are also polyclonal.22

Histopathologic features of HIV MCD. (A) Lymph node shows a small follicle with relatively atrophic germinal center and mildly expanded mantle zone. The tissue outside the follicle (interfollicular area) is rich in vessels and plasma cells (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×40). (B) Higher magnification of the follicle, including the mantle zone (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×100). (C) Higher magnification of the interfollicular area (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×100). (D) Within the mantle zone, there are several large cells with nucleoli, the so-called “plasmablasts” (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×600).

Histopathologic features of HIV MCD. (A) Lymph node shows a small follicle with relatively atrophic germinal center and mildly expanded mantle zone. The tissue outside the follicle (interfollicular area) is rich in vessels and plasma cells (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×40). (B) Higher magnification of the follicle, including the mantle zone (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×100). (C) Higher magnification of the interfollicular area (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×100). (D) Within the mantle zone, there are several large cells with nucleoli, the so-called “plasmablasts” (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×600).

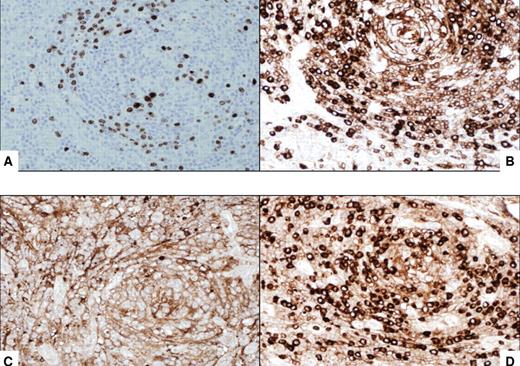

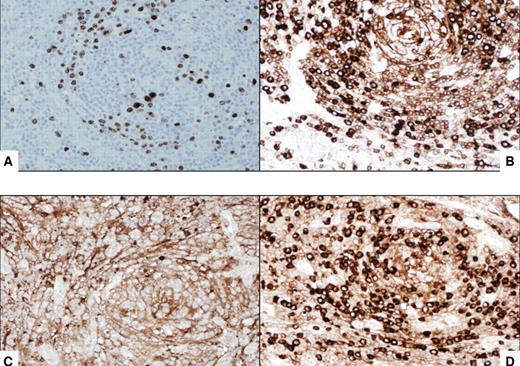

Immunocytochemical features of HIV MCD plasmablasts. (A) On immunohistochemistry, the large lymphoid cells with nucleoli, the so-called “plasmablasts,” harbor HHV8 virus as demonstrated by the presence of HHV8–latent nuclear antigen-1. The cells express IgM (B) and lambda light chain (D) and are negative for kappa light chain (C). All original magnifications are ×600.

Immunocytochemical features of HIV MCD plasmablasts. (A) On immunohistochemistry, the large lymphoid cells with nucleoli, the so-called “plasmablasts,” harbor HHV8 virus as demonstrated by the presence of HHV8–latent nuclear antigen-1. The cells express IgM (B) and lambda light chain (D) and are negative for kappa light chain (C). All original magnifications are ×600.

The diagnosis of active HIV MCD requires not only the histopathologic findings described but also clinical features of active disease. Although there are no evidence-based “gold standard” criteria for establishing a diagnosis of active HIV MCD, the French Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA 117 CastlemaB trial group recognizing this deficiency have described criteria to define an attack of HIV MCD.23 These are shown in Table 2. Patients require a fever, a raised serum C-reactive protein more than 20 mg/L in the absence of any other cause, and 3 of 12 additional clinical findings. Unfortunately, the incidence of each of these criteria is not described in the CastlemaB trial and have not all been prospectively collected in our cohort of patients. Interestingly, although both clinical and radiologic pulmonary manifestations appear to be common in HIV MCD,24,25 localized central nervous system involvement by MCD, which may mimic meningioma,26 has not been described in the context of HIV MCD. Similarly, the combination of peripheral neuropathy and monoclonal paraprotein with or without other features of POEMS is well recognized in plasma cell MCD but is only rarely seen in patients with HIV.27 Nevertheless, the combination of pyrexia, lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly with a raised C-reactive protein should alert clinicians to the possibility of this diagnosis and prompt investigations.

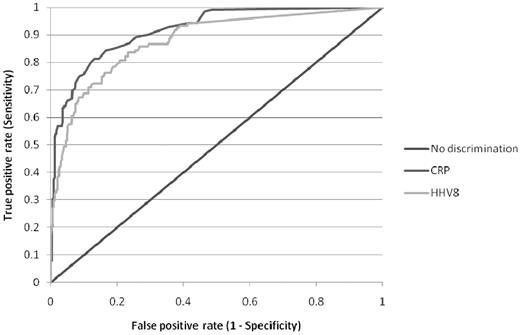

The only additional investigation that is of clinical value in aiding diagnosis is quantification of KSHV DNA levels in the plasma or peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Numerous published studies have shown that KSHV DNA is almost always detectable in the blood of patients with active HIV MCD and that levels of KSHV DNA correlate with symptomatic disease.8,9,11,16,–18,28 In contrast, KSHV DNA is only detectable in a minority of patients with KS, and the levels of KSHV DNA are significantly lower.6,28 Marcelin et al went as far as to suggest that, in a patient with KS, a very high blood level of KSHV DNA may point to a diagnosis of HIV MCD,28 and I agree with them. Although some groups have studied KSHV DNA levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and others have measured plasma levels, it appears that these correlate well,29 so I use plasma levels that are cheaper to assay. Analysis of matched plasma KSHV DNA measurements and C-reactive protein estimations in patients with HIV MCD suggest that there is little difference between these 2 parameters in predicting disease activity (Figure 3).

Receiver operating characteristic curve of serum C-reactive protein and plasma KSHV DNA in distinguishing active or remission of HIV MCD. A total of 471 matched C-reactive protein and KSHV DNA samples were available from 45 patients with HIV MCD either in clinical remission (332) or during an active episode (139) of HIV MCD.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of serum C-reactive protein and plasma KSHV DNA in distinguishing active or remission of HIV MCD. A total of 471 matched C-reactive protein and KSHV DNA samples were available from 45 patients with HIV MCD either in clinical remission (332) or during an active episode (139) of HIV MCD.

Occasionally, patients present with clinical symptoms in keeping with HIV MCD, elevated blood KSHV DNA levels, and peripheral lymphadenopathy, but an initial lymph node biopsy fails to confirm the diagnosis. In these circumstances, I advocate undertaking an 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan. HIV MCD is fluorodeoxyglucose avid, and this may help in choosing which gland to biopsy next.30

Clinical management

As with many rare and relatively newly recognized illnesses, a standard approach to clinical management has yet to be formed, and the evidence for much of the treatment given is based on small case series, open-label trials, and personal experience. Numerous approaches, including treatment with antiretrovirals, antiherpesvirus agents, single-agent and combination chemotherapy, and monoclonal antibody therapy, have all been advocated. There appears to be a consensus emerging that rituximab with or without etoposide chemotherapy is appropriate therapy for attacks of HIV MCD and that there may be a role for either rituximab or the antiherpes agent valganciclovir as maintenance therapy.38

Rituximab

Early series reported the use of cytotoxic chemotherapy for HIV MCD; and although remission rates were high, in the largest series treated before the introduction of HAART, 14 of 20 patients died and the median survival was only 14 months.39 The introduction of HAART and the addition of rituximab to the therapeutic options have resulted in a change in approach and improved outcomes. Although KSHV-infected plasmablasts frequently do not express high levels of CD20,40 numerous case series and 2 open-label studies have used rituximab. One study of 21 patients with newly diagnosed HIV MCD reported a radiologic response rate of 67%, and the overall and disease-free survival rates at 2 years were 95% and 79%, respectively.41 The second prospective study enrolled 24 patients with HIV MCD who were classified as chemotherapy-dependent. Rituximab induced a sustained remission of 1-year duration in 17 of 24 (71%) patients and the 1-year overall survival was 92%.23 Both trials reported an exacerbation of KS in patients who had KS at enrollment despite patients receiving HAART, and it is my policy to treat the KS with liposomal anthracyclines. However, 2 case series have described patients with aggressive HIV MCD and organ failure who failed to respond to rituximab monotherapy.42,–44 For this reason, I now follow a stratified approach to the management of HIV MCD, reserving rituximab monotherapy for patients without evidence of organ failure and using chemotherapy with rituximab for those with aggressive disease based on poor performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status > 1) and evidence of organ damage, usually lung involvement, hemophagocytic syndrome, or severe hemolytic anemia.

Chemotherapy

Both single-agent and combination cytotoxic chemotherapy has been used in a number of patients with HIV MCD with various success.10,12,39,43,45,,,,,,,,,–55 Although rapid resolution of symptoms has been reported in patients with active disease, relapses occur frequently and the progression-free survival is often brief. A strategy using maintenance oral etoposide (100-200 mg/m2, weekly) has been adopted in France.23,39 However, the oncogenicity of etoposide, in particular the risk of secondary acute myeloid leukemia,56 limits this approach. The encouraging results observed with rituximab monotherapy in patients with less aggressive HIV MCD have led to a combined immunochemotherapy approach in aggressive HIV MCD using rituximab with combination chemotherapy27,57 or rituximab with single-agent etoposide.38 The optimal chemotherapy has not been established; and although several case reports described successful treatment of HIV MCD with the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristin, prednisone (CHOP) regimen without rituximab,48,50,52,55 there is greater experience with rituximab and etoposide. I have used this approach combining weekly rituximab (375 mg/m2) with intravenous etoposide (100 mg/m2) for 4 weeks in 13 patients stratified as having aggressive HIV MCD with an overall survival at 2 years of 85%. In contrast, 23 patients with low-risk HIV MCD have been treated with rituximab monotherapy (375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks) and the overall survival at 2 years is 100%.

HAART

The algorithm of care for HIV MCD includes the use of HAART, although it is uncertain whether this contributes to control of the HIV MCD. First, epidemiologic evidence suggests that neither nadir CD4 cell count nor use of HAART influences the risk of HIV MCD.6 Second, a significant number of patients develop HIV MCD, whereas their HIV is well suppressed on HAART. The systematic literature review included 48 patients diagnosed with HIV MCD in the HAART era, of whom 64% were on HAART at the time of MCD diagnosis.7 Our series includes 55 patients diagnosed with HIV MCD in the HAART era of whom 24 (44%) were on HAART at the time of MCD diagnosis and of those patients 20 (83%) had plasma HIV viral loads less than 400 copies/mm3. The failure of HAART to control HIV MCD is also supported by case reports, which include a description of acute deterioration of MCD symptoms on starting HAART.58,–60 Nevertheless, it is my practice to ensure all patients diagnosed with HIV MCD are treated with HAART as well as rituximab with or without etoposide. This approach may limit both the decline in CD4 cell counts attributable to the chemotherapy and the reactivation of KS related to the immunotherapy. As with the management of HIV-associated lymphomas with chemotherapy, it is my practice to initiate opportunistic infection prophylaxis in patients with low CD4 cell counts or whose CD4 cell counts are probable to decline with chemotherapy.61

Antiherpesvirus agents

Several antiherpesvirus agents, including cidofovir, foscarnet and ganciclovir, have been reported to show activity against KSHV in vitro.62 These agents have been studied in HIV MCD with limited success: 0 of 7 patients responded to cidofovir,16,18,63 2 of 4 patients achieved remission with foscarnet,60,63,–65 whereas ganciclovir and its oral derivative valganciclovir induced remission in 1 patient and reduced the frequency of relapse in a further 2 patients.11 None of these agents achieved the impressive remission rates documented with rituximab in much larger studies.

Tocilizumab

In addition to rituximab, there is experience with another monoclonal antibody in MCD in patients who are HIV-seronegative. The contribution of high plasma levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) to the symptomatology of HIV MCD, whether the IL-6 is derived from the host (hIL6) or KSHV virus (vIL6), has led to attempts to block this pathway. Tocilizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the IL-6 receptor. In Japan 28 HIV-negative adults with MCD were treated in an open-label study and symptoms, lymphadenopathy and inflammatory markers all improved.66 However, not only were these patients all HIV-seronegative, only 2 of 28 patients were seropositive for KSHV. It is disappointing that no studies in HIV MCD have been conducted or reported using this monoclonal antibody, which is now marketed for refractory rheumatoid arthritis.

Response evaluation

The definition of attacks and hence the criteria for evaluating disease response to therapy have not been established for HIV MCD. Although the criteria for disease activity have been clarified in the CastlemaB study,23 I remain uncertain whether it is best to evaluate response clinically, radiologically, biochemically, or virologically. For example, in the open label study of rituximab, the clinical symptoms resolved in 95%, 67% achieved a radiologic response by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria, the improvement in biochemical parameters varied from 100% (for resolution of anaemia) to 31% (for normalization of C-reactive protein), whereas cytokine levels such as IL-6 normalized in 89%, and 80% achieved undetectable plasma KSHV DNA viral loads.41

Relapse

HIV MCD is a relapsing and remitting illness; and although there has been little emphasis on second or subsequent line therapy, it is clear that relapse flares may occur at any CD4 cell count and are not prevented by good HIV control by HAART.8,,,–12 In my experience, one-fourth of patients with HIV MCD will have relapsed by 3 years of follow-up, and retreatment with rituximab have achieved second remissions.67

Maintenance therapy

Because there is an appreciable risk of relapse in HIV MCD that is not diminished by HAART, groups have explored the role of both rituximab and antiherpesvirus agents as maintenance therapy. The CastlemaB trial enrolled 24 patients who were chemotherapy dependent into a prospective open-label study of 4 infusions of rituximab at weekly intervals and cessation of the chemotherapy.23 One year later, 71% were alive in stable remission and the overall survival rate was 92%. This result may encourage clinicians to consider maintenance rituximab therapy; however, 1 patient died of acute respiratory failure of undetermined origin. Similarly, the AIDS malignancy consortium trial 010 randomized patients with HIV-associated lymphoma to receive CHOP or R-CHOP (with 3-monthly maintenance rituximab). An excess of respiratory infection related deaths was recorded among patients in remission who received maintenance rituximab.68 An alternative approach to maintenance therapy is offered by the oral antiherpes agent valganciclovir, and this has been adopted in some algorithms of care,38 although there are limited published data to support this. In a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial, valganciclovir has been shown to reduce oropharyngeal shedding of KSHV in both HIV-seronegative and -seropositive persons.69 I do not currently offer patients in remission maintenance therapy, although I think that the approach with valganciclovir looks the most promising option.

Follow-up

There are no clear guidelines for the follow-up of patients treated for HIV MCD. It is my practice to monitor patients at 3 monthly intervals with clinical examination and quantitative estimation of the plasma KSHV DNA. However, although the plasma KSHV DNA level correlates with symptomatic disease,8,9,11,16,–18,28 it is not clear that a rising level predicts relapse. Another important issue in the follow-up of patients with HIV MCD is the very high risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma recorded in 2 published series. In a French series of 60 patients over a median follow-up of 20 months, 14 developed NHL and 11 of these lymphomas were associated with KSHV (6 plasmablastic and 3 primary effusion lymphomas).70 Similarly, in an Australian series of 11 patients with HIV MCD with a median follow-up of 48 months, 4 developed lymphoma.12 Although Eric Oksenhendler, whose group at Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris has one of the largest cohort of patients with HIV MCD, has suggested that this risk may be declining since the introduction of HAART.38 The treatment and the clinical outcome of these KSHV-positive, CD20-negative lymphomas remain uncertain. It is my impression that they have a worse prognosis than diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in this population and may warrant a more aggressive approach.

Future directions

The future management of HIV MCD may incorporate screening with a combination of plasma KSHV DNA and cytokines as well as greater use of antiherpes virus agents in the chronic control of MCD as maintenance therapy and possibly in primary prevention strategies. However, both approaches are expensive and probably limited to nations with established market economies. The diagnosis of HIV MCD requires high levels of expertise and expensive specialist immunocytochemistry, and this may account for the very few reported cases described in African cohorts where the burdens of HIV and KSHV are greatest. Numerous initiatives, including the International Network for Cancer Treatment Research iPath telepathology and the Subsaharan Africa Lymphoma Consortium, aim to improve histopathology expertise in developing nations by collaborative mentoring and to expand access within these communities to limited panels of immunostains. Inevitably, much of this article is based on opinion along with the limited available evidence; and as a final personal view, I encourage clinicians to become involved with both International Network for Cancer Treatment Research and Subsaharan Africa Lymphoma Consortium.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Professor Kikkeri Naresh (Department of Haematopathology, Imperial College, London) for kindly providing histopathologic images and Professor Justin Stebbing and Dr Adam Sanitt (Department of Oncology, Imperial College, London) for their assistance with the receiver operating characteristic analysis.

Authorship

Contribution: M.B. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mark Bower, Department of Oncology, Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, 369 Fulham Rd, London, United Kingdom, SW10 9NH; e-mail: m.bower@imperial.ac.uk.