Abstract

This study investigated the role of the ETS transcription factor Fli-1 in adult myelopoiesis using new transgenic mice allowing inducible Fli-1 gene deletion. Fli-1 deletion in adult induced mild thrombocytopenia associated with a drastic decrease in large mature megakaryocytes number. Bone marrow bipotent megakaryocytic-erythrocytic progenitors (MEPs) increased by 50% without increase in erythrocytic and megakaryocytic common myeloid progenitor progeny, suggesting increased production from upstream stem cells. These MEPs were almost unable to generate pure colonies containing large mature megakaryocytes, but generated the same total number of colonies mainly identifiable as erythroid colonies containing a reduced number of more differentiated cells. Cytological and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses of MEP progeny in semisolid and liquid cultures confirmed the drastic decrease in large mature megakaryocytes but revealed a surprisingly modest (50%) reduction of CD41-positive cells indicating the persistence of a megakaryocytic commitment potential. Symmetrical increase and decrease of monocytic and granulocytic progenitors were also observed in the progeny of purified granulocytic-monocytic progenitors and common myeloid progenitors. In summary, this study indicates that Fli-1 controls several lineages commitment decisions at the stem cell, MEP, and granulocytic-monocytic progenitor levels, stimulates the proliferation of committed erythrocytic progenitors at the expense of their differentiation, and is a major regulator of late stages of megakaryocytic differentiation.

Introduction

Mature blood cells in adults are permanently regenerated from a limited pool of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) localized in the bone marrow. This process occurs through the hierarchical generation of intermediate progenitors with more and more restricted differentiation and proliferation potential that can be prospectively purified. According to current models, myeloid lineages are derived from a common myeloid progenitor (CMP) generating 2 distinct bipotent progenitors, the megakaryocytic-erythrocytic progenitors (MEPs) and the granulocytic-monocytic progenitors (GMP).1 MEPs generate in turn erythrocytic and megakaryocytic monopotent progenitors, whereas GMP generate granulocytic and monocytic monopotent progenitors. Increasing data also indicate an alternative pathway generating MEPs directly from HSCs.2-4

All this process is controlled by permanent crosstalk between extracellular signals and intracellular regulatory networks of transcription factors. Although having no instructive role, erythropoietin (EPO) is the major cytokine controlling erythropoiesis through the stimulation of proliferation and survival of committed erythrocytic progenitors expressing the specific receptor EPOR.5 Thrombopoietin (TPO) is the major cytokine controlling megakaryopoiesis through the stimulation of proliferation and differentiation of committed megakaryocytic progenitors expressing the specific receptor TPOR/MPL. Contrasting with the strict dependence of mature red cells production on EPOR signaling, significant platelets production can occur without TPO signaling.6 For example, stromal cell–derived factor-1 is known to stimulate platelets production independently of TPO.7 Furthermore, Notch signaling stimulates megakaryopoiesis directly from HSCs even in the absence of TPO.8 More recently, in vitro cultures have shown that TPO induces BMP4 production and autocrine stimulation of megakaryopoiesis initiated from human CD34+ progenitors.9

The specific combination of transcription factors allowing erythrocytic or megakaryocytic lineages commitment remains poorly understood.10,11 Indeed, both lineages are dependent on many common transcription factors including Gata1, Tal1, Nfe2, Gfi1b, Zbp89, as well as cofactors like Fog1, Lmo2, or Ldb1 acting in large multiprotein complexes such as Fog1/Gata1/Zbp8912 or Gata1/Tal1/Lmo2/Ldb1.13 No differential requirement of these factors for either lineage has been reported to date. In contrast, low levels of c-Myb favor megakaryocytic at the expense of erythrocytic lineage,14 whereas the same is true for Stat5.15 Aml1/Runx1 cooperates with Gata1 to activate some megakaryocytic promoters,16 and conditional inactivation of Runx1 gene in adult inhibits megakaryocytic maturation but has no effect on erythrocytic differentiation.17 Eklf and Fli-1 are also known binding partners of Gata1 that competitively activate either erythrocytic or megakaryocytic promoters, respectively.18 Fli-1–mediated activation of megakaryocytic promoters is further dependent on the cooperation with Fog1 and/or Aml1.19 We20 and others21,22 recently demonstrated that Eklf promotes the commitment of bipotent progenitors toward erythrocytic at the expense of megakaryocytic differentiation. Reciprocally, concordant results from 2 different mouse models of Fli-1 gene disruption clearly established that the thrombocytopenia observed in Fli-1−/− embryos is at least partially due to a maturation defect of fetal liver megakaryocytes.23-25 Further studies have shown that this contribution of Fli-1 to late stages of megakaryocytic differentiation is shared by at least 2 other ETS family transcription factors, Gapbα26 and Erg.27 However, the real contribution of Fli-1 in the commitment decision toward megakaryocytic versus erythrocytic lineage remains rather controversial. For example, somewhat contradictorily to normal numbers of colony-forming unit megakaryocyte (CFU-MK) progenitors in Fli-1−/− fetal liver,23 Fli-1−/− embryonic stem (ES) cells failed to generate megakaryocytic colonies in vitro, and the in vitro generation of megakaryocytic cells from Fli-1−/− AGM (aorta-gonad-mesonephros) was almost completely suppressed.28 Furthermore, Fli-1−/− ES cells failed to contribute to bone marrow megakaryocytes in reconstituted chimeric mice, whereas Fli-1+/− ES cells displayed a massively increased contribution to erythrocytic cells compared with wild-type ES cells.25 Taken together, these data raise the intriguing possibility that megakaryocytic commitment might be more stringently dependent on Fli-1 in adult and during early development than during fetal life.

To address the role of Fli-1 in adult hematopoiesis, we have generated new transgenic mice allowing inducible Fli-1 gene disruption. We found that Fli-1 gene disruption in adult mice induced a mild thrombocytopenia associated with a maturation defect of bone marrow megakaryocytes as previously observed in fetal liver. Further investigations revealed that Fli-1 gene deletion modified commitment decisions at several hierarchical levels of myelopoiesis characterized by a specific increase of MEPs that are prone to preferential and accelerated erythrocytic differentiation at the expense of megakaryocytic differentiation and by an unaltered number of GMP that are prone to preferential monocytic at the expense of granulocytic differentiation.

Methods

Generation of fli-1fl/fl and fli-1Δ/fl mice

Fli-1 gene exon 9 and its upstream and downstream flanking sequences were amplified from ENS ES cell29 DNA using primers indicated in supplemental Table 1A (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and inserted into BamH1/Nhe1, SacII/Not1, and Xho1/Kpn1 sites of the KSloxPfrtNeoBS (3′-5′) vector,30 respectively. The resulting targeting construct contained 2 loxP sites flanking Fli-1 exon 9 coding sequence, 1 Frt-flanked neomycine resistance cassette and 2 homology arms (supplemental Figure 1A). ENS ES cells were transfected with linearized targeting vector by electroporation, and homologous recombinant clones were screened among G418-resistant clones by Southern blot analysis as described in supplemental Figure 1B. The neomycine-resistance cassette gene was excised with Flp recombinase by transfection with the pCAGGS-Flpe vector31 and selection with puromycin for 72 hours. Correctly targeted clones obtained after neomycine-resistance cassette excision were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts and implanted into recipient females. Germ line transmission of the Fli-1fl allele was obtained for 1 of 4 chimeric mice generated with ES recombinant clone 79.8 of genotype Fli-1+/Fli-1fl. Constitutively deleted allele Fli-1Δ (supplemental Figure 1A) has been generated in vivo by crossing mouse females of genotype Fli-1+/Fli-1fl with Sycp1Cre transgenic males expressing Cre recombinase during male meiosis.32 Mice harboring either Fli-1Δ or Fli-1fl alleles were then crossed with Mx1-Cre transgenic mice33 expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the interferon inducible Mx1 gene promoter to generate couples of mice with genotypes Fli-1fl/Fli-1Δ or Fli-1fl/Fli-1fl harboring or not the Mx1-Cre transgene. Between 8 and 12 weeks after birth, couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice of either Fli-1fl/Fli-1Δ or Fli-1fl/Fli-1fl genotypes were injected intraperitoneally 3 times on alternate days with 300 μg of polyinosinic:polycytidic acid (poly I:C; Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 0.9% NaCl/20 g body mass. Injected mice were killed for analyses between 8 and 10 days after the first injection. Mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the ALECS-SFP animal facilities of the Faculté de Médecine Lyon-Est (Université Claude Bernard, Lyon1, France) and experimentations were performed according to procedures approved by the local animal care and experimentation authorities (Ministère Délégué de la Recherche et des Nouvelles Technologies, agreement no. 4936; Direction des Services Vétérinaires, agreement nos. 69266317 and 7462).

Hematopietic cells collection and counting

Peripheral blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and mixed with EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). Red cell, white cell, and platelet counts were determined manually using Mallassez counting chambers after appropriate dilutions in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Hayem blue, or BD Unopette (BD Biosciences) solutions, respectively. Bone marrow cells (BMC) were flushed from femurs and tibiae, pooled, washed in PBS containing 0.5% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 2mM EDTA, and made in single-cell suspensions by repeated pipetting and filtering through a 100-μm nylon mesh. Single-cell suspensions from spleen and thymus were prepared using the same procedure after initial organs mincing using scissors and clamps.

Flow cytometric analyses and cell sorting

Relative proportions of mature cells were determined using a FACSCalibur or FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) after single or double labeling with the following monoclonal conjugated antibodies: anti-CD71–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and anti-Ter119–phycoerythrin (PE) for erythrocytic lineage, anti-CD41–FITC for megakaryocytic lineage, anti–Gr-1–PE, and anti-CD11b–FITC for granulocytic/monocytic lineages, anti-CD45R(B220)–PE, and anti-IgM–FITC for B-lymphoid lineage, anti-CD4–PE and anti-CD8a–FITC for T-lymphoid lineages, and anti-NK1.1–PE for natural killer (NK) lineage. All these antibodies were purchased from Caltag Laboratories except for CD41 (Acris Antibodies).

For quantification and sorting of CMP, MEP, and GMP progenitors, BMC suspensions were treated with red blood cells ACK lysing buffer (Lonza) before filtering through a 70- or 100-μm cell strainers (BD Biosciences). BMC suspensions were then labeled with a lineage cocktail of biotinylated antibodies (Lineage cell depletion kit; Miltenyi Biotec) supplemented with biotinylated anti–Sca-1 (BD Pharmingen), anti-CD3 (BD Pharmingen), anti-ILR7 (eBiosciences), and anti-CD19 (Serotec). After magnetic depletion of lineage-positive cells using MS columns (Miltenyi Biotec), Lin−Sca− cells were numbered and further labeled with streptavidin-PE-Cy7 (BD Pharmingen) for the detection of residual biotinylated stained cells and with anti–c-Kit–APC (BD Pharmingen), anti-CD34–FITC (e-Biosciences), and anti–Fcγ-RII/III–PE (BD Pharmingen) antibodies. MEPs, CMPs, and GMPs were then identified as previously described34 as the Lin−Sca−Kit+ Fcγ-RII/IIIlow/CD34low, Fcγ-RII/IIIlow/CD34high, and Fcγ-RII/IIIhigh/CD34high subpopulations, respectively, and sorted using FACSAria or FACSVantage cell sorters and DIVA software (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded by 7-aminoactinomycin D staining (Sigma-Aldrich).

Colony assays

Hematopoietic progenitors in unfractionated BMC suspensions were evaluated by colony assays scored at day 7 using MethoCultRSFBIT M3236 methylcellulose semisolid medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 20% FCS (StemCell Technologies), mIL3 (10 ng/mL) and huEPO (3.3 U/mL). Hematopoietic progenitors in sorted MEP, GMP, and CMP populations were evaluated by colony assays scored at day 7 using MethoCult M3234 methylcellulose semisolid medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 30% FCS, murine interleukin 3 (mIL3; 10 ng/mL), murine stem cell factor (mSCF; 50 ng/mL), mFlt-3l (5 ng/mL), murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (mGM-CSF; 5 ng/mL), huIL11 (50 ng/mL), huEPO (2 U/mL), and mTPO (50 ng/mL). Megakaryocytic progenitors (CFU-Mk) in unfractionated BMC suspensions were evaluated by colony assays using MegaCult-C collagen semisolid medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with mIL3 (10 ng/mL) and mTPO (50 ng/mL) and by numbering acethylcholinesterase-positive colonies at day 7. All cytokines were purchased from PeproTech except huEPO (kindly provided by F. Nicolini).

Liquid cultures of sorted MEPs

MEPs were seeded at 2000 cells/mL in Iscove modified Dulbecco liquid medium supplemented with either 10% FCS and myeloid cytokines exactly as previously described35 or with 15% BIT 9500 serum substitute (StemCell Technologies) and only SCF, IL3, IL11, TPO, and IL6.9 After 5 days of culture, viable cells excluding trypan blue were numbered, and the relative proportions and maturation of erythrocytic and megakaryocytic cells were determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) after double-labeling with labeled anti-CD71 and anti-Ter119, anti-CD61 and anti-CD41, or anti-CD41 and anti-CD42b antibodies. For single-cell progeny analyses, single MEPs were plated in 96-well plates using a FACSVantage flow cytometer coupled with single-cell depositor in 60 μL of the same liquid medium with serum. Each individual well was evaluated by light microscopy after 6 to 7 days of culture to determine the proportion of wells containing at least 1 identifiable living cell as well as the relative proportions of erythrocytic colonies (containing a large number of small cells), megakaryocytic colonies (containing a small number of large cells), or mixed colonies as illustrated in supplemental Figure 3.

Genotyping and control of deletion efficiency

Mice genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis using crude lysates of tail biopsies using primers indicated in supplemental Table 1B. Hematopoietic cells DNA used to control deletion efficiencies were prepared either with QIAampDNA Mini kit (QIAGEN; for > 50 000 cells) or with NucleoSpin Tissue XS kit (Macherey-Nagel; < 50 000 cells). Deletion efficiencies were determined either by densitometry of PCR products obtained with primers KO14 and KO8 (supplemental Table 1B) or by quantitative (q)PCR using Fli-1 exon 9 and 129K primers located in α globin locus used as standard reference (supplemental Table 1D). Quantitative PCRs were performed using Light-cycler 480 SybR-Green-Master-Roche kit on a Mx3000 PTM PCR instrument and analyzed using Mx Pro software (Stratagene). Fli-1 genotyping of isolated colonies was performed using primers indicated in supplemental Table 1C.

Single-cell RT-PCR analyses of large mature megakaryocytes

Bone marrow large mature megakaryocytes were purified by 2 rounds of sedimentation on discontinuous 0%-3% BSA gradient as previously described36 (4 mL 3% BSA/PBS in a 15-mL Falcon tube overlaid with 4 mL 1.5% BSA/PBS and then 4 mL BMC suspension in PBS; sedimentation 40 minutes at 1g). Single mature megakaryocytes were then pipeted individually under visual microscope control and transferred in Eppendorf tubes. Large mature megakaryocytes from MEP liquid cultures were collected directly without enrichment after appropriate dilution of the cells suspension. Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed in the same tubes in 10 μL using 3′ Actin and Fli-1 primers (supplemental Table 1E), followed by PCR and then nested PCR on 1/50th of the first PCR.

Cytological analyses

Cell cytospins were examined under light microscope after either May-Grünwald-Giemsa or acetylycholinesterase staining.

Western blot analyses

Western blots analyses were performed on total cell lysates as previously described18 using the following antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti Fli-1 (sc-356; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-Actin (sc-8432; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Results

Fli-1 gene deletion in adult mice induces mild thrombocytopenia associated with maturation defect and a drastic reduction of CFU-MK progenitors

A conditionally disrupted allele of Fli-1 (Fli-1fl) has been generated by inserting 2 loxP sequences flanking the Fli-1 gene exon IX encoding the whole ETS DNA binding and C-terminal domains of the Fli-1 protein (supplemental Figure 1A). A constitutively disrupted allele (Fli-1Δ) has been also generated in vivo by crossing transgenic mice harboring the conditional Fli1fl allele with Sycp1Cre mice expressing Cre recombinase in primary spermatocytes32 (supplemental Figure 1A-C). All subsequent analyses were performed by comparing couples of mice of the same Fli-1 genotype (Fli1fl/Fli1fl or Fli1Δ/Fli1fl) carrying (Cre+) or not carrying (Cre−) the Mx1-Cre gene encoding interferon inducible Cre recombinase33 and submitted to the same polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pIpC) injection protocol. Fli-1 gene deletion efficiencies detected in BMCs from injected Cre+Fli1fl/Fli1fl or Fli1Δ/Fli1fl mice ranged from 60% up to 90% and were associated with proportional decrease in Fli-1 protein levels (supplemental Figure 2). Deletion efficiencies and Fli-1 protein decreases in spleen and thymus were slightly and strongly lower than in bone marrow, respectively (supplemental Figure 2).

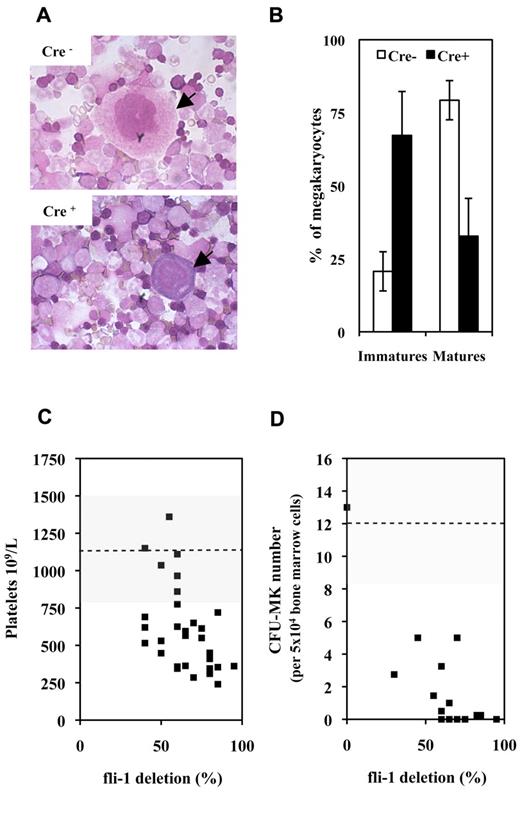

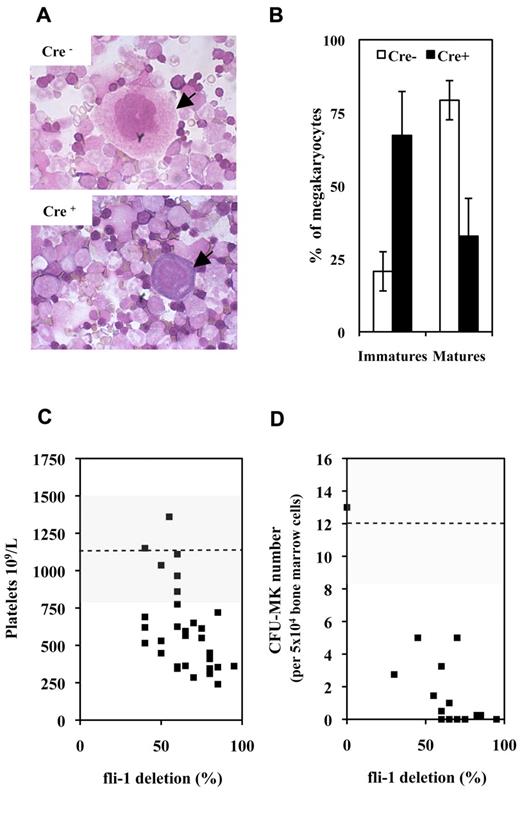

A first series of experiments performed on couples of injected Fli1fl/Fli1fl Cre+ and Cre− mice revealed that injected Cre+ mice were characterized by a significant 33% mean decrease in circulating platelets number (630 ± 361 vs 950 ± 382 109/L; P < .05, n = 9) with no significant variation of circulating red and white cell numbers. Concomitantly, analyses of BMC cytospins revealed a marked decrease in the mature/immature ratio of megakaryocytes in injected Cre+ mice indicating a maturation defect (Figure 1A-B). In addition to this maturation defect, injected Cre+ mice were characterized by a significant 2-fold decrease in CD41+ cells (Table 1A) and by a 10-fold decrease in bone marrow CFU-MK (Table 1B). Similar decrease in circulating platelets and bone marrow CFU-MK numbers were observed by comparing couples of injected Fli1fl/Fli1Δ Cre+ and Cre− mice, and a compilation of the results obtained for all Cre+ and Cre− couples of mice analyzed so far is presented in Figure 1C and D, respectively. Intriguingly enough, although the decrease in platelets and CFU-MK numbers were both proportional to the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion, the decrease in CFU-MK appeared much more drastic than the decrease in platelets numbers. Altogether, these data indicated that loss of Fli-1 in adult mice induced a mild thrombocytopenia associated with a marked reduction of megakaryocytic progenitors and a maturation defect of megakaryocytes present in bone marrow.

Fli-1 gene deletion induces a mild thrombocytopenia associated with megakaryocytes maturation defects and drastic decrease in CFU-MK numbers. (A) Representative fields of BMCs cytospins from pIpC-injected Cre+ and Cre−Fli1fl/Fli1fl mice. Arrows indicate representative mature and immature megakaryocytes in Cre− or Cre+ cytospins, respectively. (B) Histogram showing significant inverted proportions of immature versus mature megakaryocytes in bone marrow between injected Cre+ or Cre− mice (P = 1.48 × 10−5 and 4.1 × 10−6 for immature and mature cells, respectively). Means and SDs from 5 different couples of injected Cre+ and Cre−Fli1fl/Fli1fl mice. (C) Diagram showing the variations in platelet numbers with respect of the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion. Dotted line and gray area indicates the mean and SD of platelet numbers in injected control Cre− mice. (D) Diagram showing the variations in CFU-MK numbers for 5 × 104 BMCs with respect of the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion (a total of 2 × 105 BMCs have been plated for each experiment). Dotted line and gray area indicate the mean and SD of CFU-MK numbers in injected control Cre− mice.

Fli-1 gene deletion induces a mild thrombocytopenia associated with megakaryocytes maturation defects and drastic decrease in CFU-MK numbers. (A) Representative fields of BMCs cytospins from pIpC-injected Cre+ and Cre−Fli1fl/Fli1fl mice. Arrows indicate representative mature and immature megakaryocytes in Cre− or Cre+ cytospins, respectively. (B) Histogram showing significant inverted proportions of immature versus mature megakaryocytes in bone marrow between injected Cre+ or Cre− mice (P = 1.48 × 10−5 and 4.1 × 10−6 for immature and mature cells, respectively). Means and SDs from 5 different couples of injected Cre+ and Cre−Fli1fl/Fli1fl mice. (C) Diagram showing the variations in platelet numbers with respect of the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion. Dotted line and gray area indicates the mean and SD of platelet numbers in injected control Cre− mice. (D) Diagram showing the variations in CFU-MK numbers for 5 × 104 BMCs with respect of the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion (a total of 2 × 105 BMCs have been plated for each experiment). Dotted line and gray area indicate the mean and SD of CFU-MK numbers in injected control Cre− mice.

Fli-1 gene deletion in adult mice increases the number of erythrocytic and NK cells and decreases the number of granulocytic cells

Further analyses of BMCs failed to detect any significant variation in the proportion of cells expressing B or T lymphoid lineage markers between injected Cre+ and Cre− mice (Table 1A). However, in addition to the decrease in megakaryocytic cells, these analyses revealed a 3-fold increase in natural killer NK1.1+ cells, a 1.5-fold increase in CD71+Ter119+ erythrocytic cells and a 2-fold decrease in Gr1++/Mac1+ granulocytic cells (Table 1A). In agreement with the increase in erythrocytic cells, the number of BFU-E (burst-forming unit erythroid) and CFU-E (colony-forming unit erythroid) erythrocytic progenitors increased by 2.2- and 1.7-fold, respectively (Table 1B). The opposite changes in the numbers of BFU-E and CFU-MK raised the intriguing possibility that a commitment switch occurred at the level of their common bipotent progenitor MEPs. Furthermore, in agreement with the decrease in granulocytic cells, the number of granulocytic progenitors CFU-G (colony-forming unit granulocytic) significantly decreased by 1.7-fold (Table 1B), whereas the number of monocytic CFU-M (colony-forming unit monocytic) progenitors symmetrically increased by 1.4-fold, although this increase was not statistically significant (Table 1B). Likewise, these symmetrical changes in the relative numbers of CFU-G and CFU-M progenitors also suggested a commitment switch occurring at the level of their common bipotent progenitor GMPs. To address these possibilities, we thus decided to analyze the progeny of purified MEP and GMP bipotent progenitors as well as of their parent multipotent progenitor CMPs.

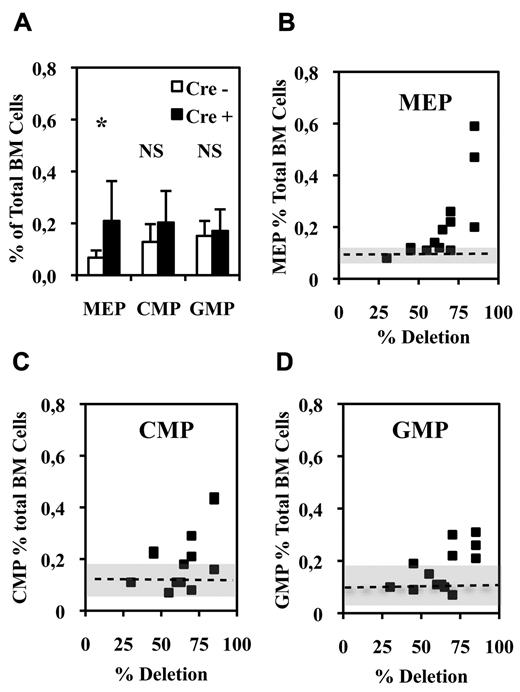

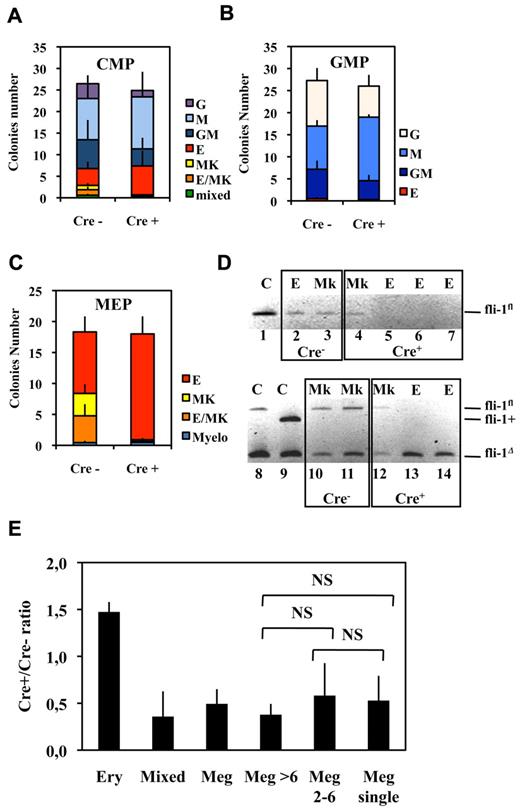

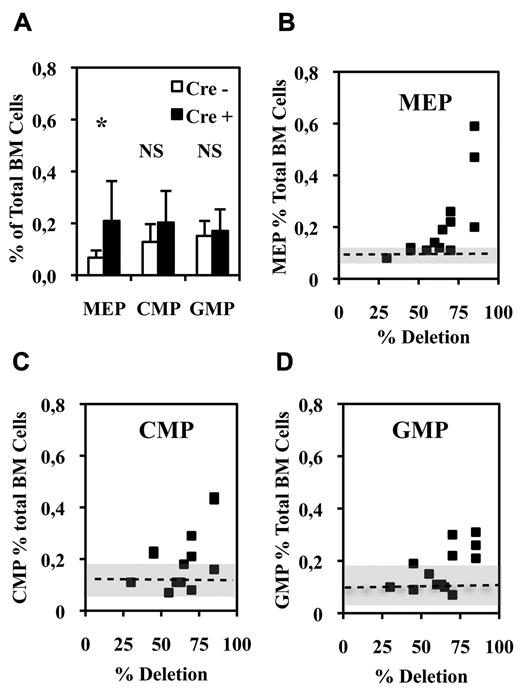

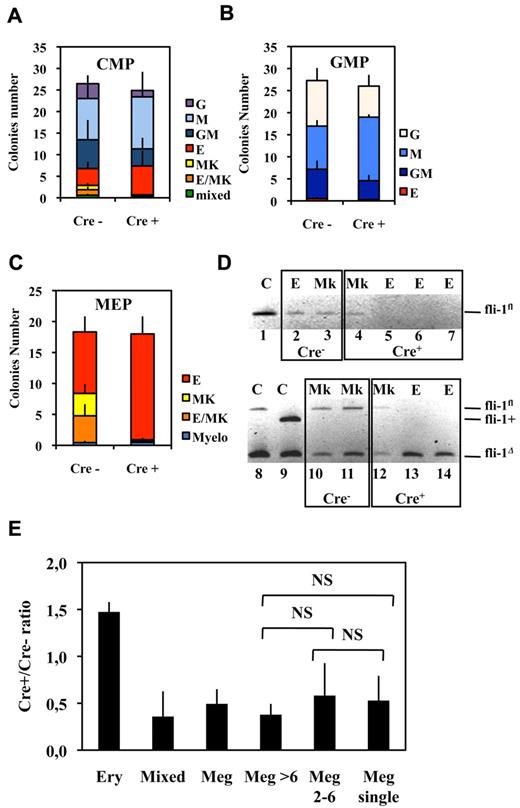

Fli-1 gene deletion enhances the number of bipotent progenitors MEP and suppresses their ability to generate mature megakaryocytic colonies in vitro

Bipotent MEPs, GMPs, and multipotent CMPs were purified from the bone marrow of injected Fli1Δ/Fli1fl Cre+ and Cre− mice according to published protocol based on their differential expression of CD16/32 and CD34.34 Compared with injected Cre− mice, injected Cre+ mice displayed a significant increase in MEP number (Figure 2A) reaching a more than 3-fold increase for the highest Fli-1 gene deletion efficiencies obtained (Figure 2B). Concomitantly, the numbers of CMPs and GMPs did not change significantly (Figure 2A), although both of them slightly increased by less than 2-fold for the highest Fli-1 gene deletion efficiencies (Figure 2C-D). The clonogenic progenies of these different classes of Cre− or Cre+ multipotent progenitors were then compared in the presence of a complete cocktail of cytokines allowing the development of all myeloid progenitors (Figure 3). As expected, Cre− CMPs generated all types of single lineage myeloid colonies as well as mixed granulo-monocytic and a few percent of mixed erythro-megakaryocytic colonies (Figure 3A left). Cre+ CMP generated the same number of colonies with an increased proportion of monocytic (M) and erythrocytic (E), a decreased proportion of granulocytic (G) but no identifiable megakaryocytic (Mk) or mixed erythro-megakaryocytic (E-Mk) colonies (Figure 3A right). Cre− and Cre+ GMPs generated the same number of only G, M, or GM colonies but also with an increase of the M to G colonies ratio for Cre+ compared with Cre− GMPs (Figure 3B). This increase in the M/G ratio occurring without any change of the total number of colonies strongly suggests that Fli-1 gene deletion slightly favors the commitment of bipotent GMPs toward monocytic at the expense of granulocytic lineage. Most strikingly, whereas Cre− MEPs generated approximately one-third of megakaryocytic or mixed erythro-megakaryocytic colonies, Cre+ MEPs generated the same total number of colonies, but belonging almost exclusively to the erythrocytic lineage (Figure 3C). PCR analyses performed on single colonies revealed that whereas Fli-1 gene deletion could be evidenced on most erythrocytic colonies derived from Cre+ MEPs (Figure 3D lanes 5-7,13,14), all the few residual megakaryocytic colonies that could be analyzed were found to be undeleted (Figure 3D lanes 4,12, and data not shown). Taken together, these results thus indicated that loss of Fli-1 led to the generation of an increased number of MEPs that became virtually unable to generate mature megakaryocytic colonies in vitro. We also analyzed the progeny of single purified Cre− or Cre+ MEPs after 7 days in liquid culture containing a full cocktail of myeloid cytokines (Figure 3E). No significant difference was found in the proportions of single Cre+ and Cre− MEPs generating viable progeny (51% vs 56%) with Cre+ MEPs generating a significant increase in the proportion of erythrocytic colonies (78% vs 53%) and a compensating decrease of mixed (4% vs 10%) and pure megakaryocytic colonies (18% vs 36%; Figure 3E). Importantly, these single-cell liquid cultures showed that all classes of pure megakaryocytic colonies containing either 1, from 2 to 6, or more than 6 megakaryocytes were decreased to the same extent in Cre+ MEP compared with Cre− MEPs (Figure 3E). Altogether, these results suggested that Fli-1 gene deletion is acting mainly by switching the commitment of MEPs toward the erythrocytic lineage rather than by lowering the proliferation or viability of their committed megakaryocytic progeny. Intriguingly however, we noticed a marked difference in the decrease of megakaryocytic and mixed colonies between single-cell liquid and methocell cultures that remained hardly explained by the slight difference in Fli-1 gene deletion efficiencies displayed by mice used in the 2 experiments (46% ± 5% vs 66% ± 11%, respectively).

Fli-1 gene deletion increases the number of bone marrow bipotent MEPs. (A) Histogram showing the percentages of the different classes of multipotent progenitors in BMCs from injected Cre+ or Cre−Fli1fl/Fli1Δ mice (means and SD from 13 different couples of injected Fli1fl/Fli1Δ Cre+ and Cre− mice). Asterisk and NS indicate significant (P < .05) and nonsignificant differences (P > .05) in paired t test, respectively. (B-D) Diagrams showing the variations in the number of the indicated progenitors in Cre+ mice with respect of the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion. Dotted lines and gray areas indicate the mean and SD of the percentage of the corresponding progenitors in Cre− mice.

Fli-1 gene deletion increases the number of bone marrow bipotent MEPs. (A) Histogram showing the percentages of the different classes of multipotent progenitors in BMCs from injected Cre+ or Cre−Fli1fl/Fli1Δ mice (means and SD from 13 different couples of injected Fli1fl/Fli1Δ Cre+ and Cre− mice). Asterisk and NS indicate significant (P < .05) and nonsignificant differences (P > .05) in paired t test, respectively. (B-D) Diagrams showing the variations in the number of the indicated progenitors in Cre+ mice with respect of the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion. Dotted lines and gray areas indicate the mean and SD of the percentage of the corresponding progenitors in Cre− mice.

Fli-1 gene deletion decreases the megakaryocytic differentiation potential of MEPs at the benefit of erythrocytic differentiation. (A-C) Histograms showing the number of different classes of colonies generated in semisolid medium containing a complete cocktail of cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l) by 100 sorted CMPs (A), GMPs (B), or MEPs (C; means and SDs from 5 different couples of injected fli1fl/fli1Δ Cre+ and Cre− mice). Note that the loss of virtually all identifiable megakaryocytic and mixed colonies in the progeny of Cre+ MEPs in C occurred without significant decrease of overall clonogenicity. (D) PCR analyses of Fli-1 gene deletion in single erythrocytic (E) or megakaryocytic (Mk) colonies derived from Cre+ or Cre− MEPs purified from Fli1Δ/Fli1fl mice. The top gel (lanes 1-7) has been generated using primers allowing the detection of undeleted allele Fli1fl only, whereas the bottom gel (lanes 8-14) has been generated using primers allowing simultaneous detection of deleted Fli1Δ and undeleted Fli1fl alleles. Lanes 1, 8, and 9 correspond to tail DNA from uninjected control mice. (E) Single-sorted bone marrow MEPs from injected Cre− or Cre+ mice were seeded at 1 cell per well in liquid medium containing complete cocktail of cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l), and the cell composition of each well was individually scored under light microscopy after 1 week of culture. Histogram shows Cre+/Cre− ratios for each class of wells containing either pure erythrocytic colony (large number of small cells and no identifiable large mature megakaryocyte), mixed colony (large number of small cells with clearly identifiable megakaryocytes), and pure megakaryocytic colony containing the indicated number of megakaryocytes (typical light microscope views of colonies are given in supplemental Figure 2). Means and SDs from analyses of 6 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice (3 couples of Fli1fl/Flifl and 3 couples of fli1fl/fli1Δ genotypes). All Cre+/Cre− ratios were significantly different from 1. NS indicates nonsignificant differences between different classes of megakaryocytic colonies (P > .05) in paired Student t test.

Fli-1 gene deletion decreases the megakaryocytic differentiation potential of MEPs at the benefit of erythrocytic differentiation. (A-C) Histograms showing the number of different classes of colonies generated in semisolid medium containing a complete cocktail of cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l) by 100 sorted CMPs (A), GMPs (B), or MEPs (C; means and SDs from 5 different couples of injected fli1fl/fli1Δ Cre+ and Cre− mice). Note that the loss of virtually all identifiable megakaryocytic and mixed colonies in the progeny of Cre+ MEPs in C occurred without significant decrease of overall clonogenicity. (D) PCR analyses of Fli-1 gene deletion in single erythrocytic (E) or megakaryocytic (Mk) colonies derived from Cre+ or Cre− MEPs purified from Fli1Δ/Fli1fl mice. The top gel (lanes 1-7) has been generated using primers allowing the detection of undeleted allele Fli1fl only, whereas the bottom gel (lanes 8-14) has been generated using primers allowing simultaneous detection of deleted Fli1Δ and undeleted Fli1fl alleles. Lanes 1, 8, and 9 correspond to tail DNA from uninjected control mice. (E) Single-sorted bone marrow MEPs from injected Cre− or Cre+ mice were seeded at 1 cell per well in liquid medium containing complete cocktail of cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l), and the cell composition of each well was individually scored under light microscopy after 1 week of culture. Histogram shows Cre+/Cre− ratios for each class of wells containing either pure erythrocytic colony (large number of small cells and no identifiable large mature megakaryocyte), mixed colony (large number of small cells with clearly identifiable megakaryocytes), and pure megakaryocytic colony containing the indicated number of megakaryocytes (typical light microscope views of colonies are given in supplemental Figure 2). Means and SDs from analyses of 6 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice (3 couples of Fli1fl/Flifl and 3 couples of fli1fl/fli1Δ genotypes). All Cre+/Cre− ratios were significantly different from 1. NS indicates nonsignificant differences between different classes of megakaryocytic colonies (P > .05) in paired Student t test.

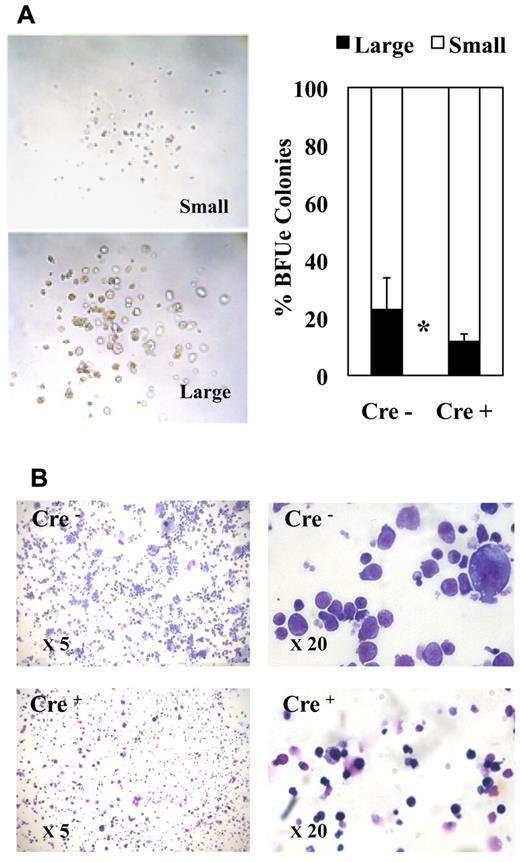

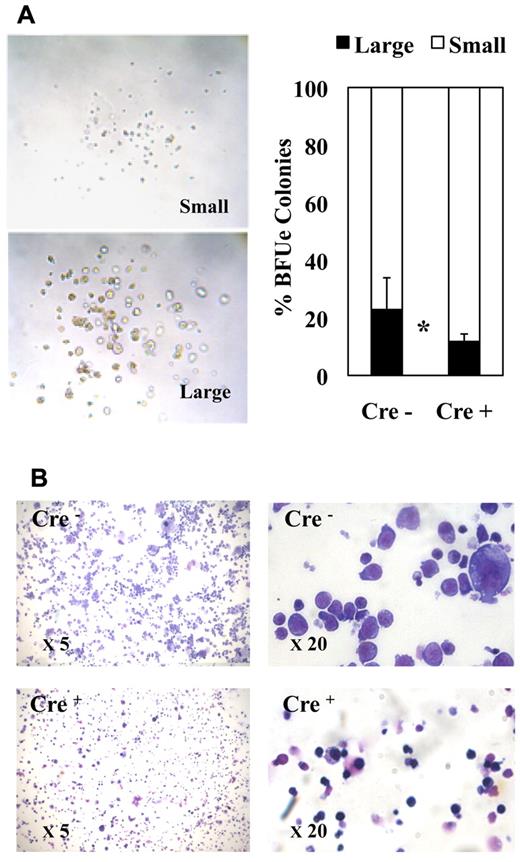

Fli-1 gene deletion reduces the number and enhances the differentiation of erythrocytic cells generated from MEPs

The morphology of erythroid colonies generated by purified MEPs in methocell was rather heterogeneous ranging from large typical BFU-E–like colonies containing a high number of thick erythrocytic cell clusters (Figure 4A left, “large” colonies) to colonies containing a small number of tiny cell clusters looking more fully differentiated (Figure 4A left, “small” colonies). Interestingly, Fli-1 gene deletion increased the relative proportion of smaller colonies (Figure 4A right). Furthermore, cell cytospins of pooled colonies revealed an increased proportion of more differentiated cells characterized by smaller size and acidophilic cytoplasm after Fli-1 gene deletion (Figure 4B). These 2 observations thus suggested that Fli-1 gene deletion accelerated the erythrocytic differentiation of MEPs at the expense of their proliferation. To address this question more directly, we compared the proliferation rate and differentiation kinetics of purified MEPs in liquid cultures containing serum and a complete cocktail of myeloid cytokines. In agreement with previous report,35 undeleted MEPs expanded up to 100-fold after 7 days in these conditions. In the same conditions, deleted MEPs expanded by only 58-fold (Figure 5A). Interestingly, deleted MEPs generated a significantly higher proportion of Ter119-positive cells (Figure 5B) among which a higher proportion already displayed reduced CD71 expression (Figure 5C) as well as reduced size (Figure 5D) indicating an increased proportion of more differentiated cells. These data thus indicated that, in addition to promote the commitment of MEPs toward the erythrocytic lineage, Fli-1 gene deletion concomitantly reduced their proliferation and accelerated their erythrocytic differentiation.

Fli-1 gene deletion decreases the size and enhances the differentiation of MEP-derived erythrocytic colonies. Equivalent numbers of bone marrow MEPs purified from injected Cre− or Cre+ mice have been cultured for 1 week in methylcellulose-medium containing a complete cocktail of cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l). (A) Left part, light microscopy view of typical large and small erythrocytic colonies obtained; right part, histogram showing the relative proportions of large and small erythrocytic colonies generated by Cre− or Cre+ MEPs (means and SDs from 3 different couples of fli1fl/fli1Δ Cre+ and Cre− mice). Statistically significant difference is indicated by asterisk. (B) Representative field of May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cytospins from pooled Cre− or Cre+ colonies at 5× magnification (left) and 20× magnification (right). Note the increased proportion of small acidophilic mature cells versus large basophilic immature erythrocytic cells in Cre+ compared with Cre− colonies.

Fli-1 gene deletion decreases the size and enhances the differentiation of MEP-derived erythrocytic colonies. Equivalent numbers of bone marrow MEPs purified from injected Cre− or Cre+ mice have been cultured for 1 week in methylcellulose-medium containing a complete cocktail of cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l). (A) Left part, light microscopy view of typical large and small erythrocytic colonies obtained; right part, histogram showing the relative proportions of large and small erythrocytic colonies generated by Cre− or Cre+ MEPs (means and SDs from 3 different couples of fli1fl/fli1Δ Cre+ and Cre− mice). Statistically significant difference is indicated by asterisk. (B) Representative field of May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cytospins from pooled Cre− or Cre+ colonies at 5× magnification (left) and 20× magnification (right). Note the increased proportion of small acidophilic mature cells versus large basophilic immature erythrocytic cells in Cre+ compared with Cre− colonies.

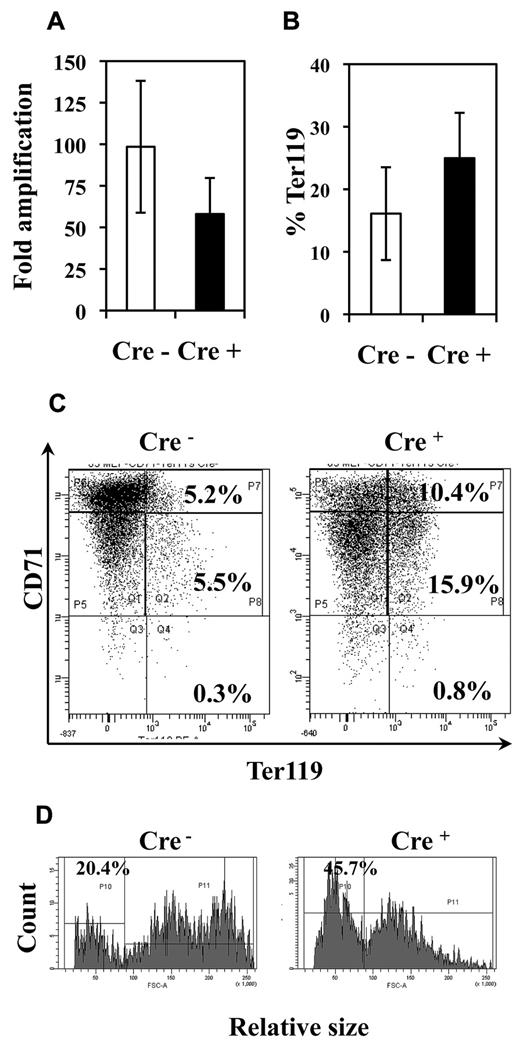

Fli-1 gene deletion decreases the proliferation and enhances the differentiation of MEP-derived erythrocytic cells. Equivalent numbers of bone marrow MEP purified from injected Cre− or Cre+ mice have been cultured for 5 days in liquid medium containing a complete cocktail of myeloid cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l). (A) Histogram showing the decrease in the fold amplification of Cre+ MEPs (means and SDs from 7 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice; P < .05). (B) Histogram showing the increased proportion of Ter119-positive cells in Cre+ MEP culture (means and SDs from the analyses of 5 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice; P < .05). (C) Typical FACS diagram of cells after Ter119 and CD71 double-labeling. (D) Typical FACS diagram showing the increased proportion of small Ter119+ differentiated cells derived from Cre+ MEPs compared with Cre− MEPs.

Fli-1 gene deletion decreases the proliferation and enhances the differentiation of MEP-derived erythrocytic cells. Equivalent numbers of bone marrow MEP purified from injected Cre− or Cre+ mice have been cultured for 5 days in liquid medium containing a complete cocktail of myeloid cytokines (IL3, IL11, TPO, EPO, SCF, GM-CSF, Flt3-l). (A) Histogram showing the decrease in the fold amplification of Cre+ MEPs (means and SDs from 7 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice; P < .05). (B) Histogram showing the increased proportion of Ter119-positive cells in Cre+ MEP culture (means and SDs from the analyses of 5 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice; P < .05). (C) Typical FACS diagram of cells after Ter119 and CD71 double-labeling. (D) Typical FACS diagram showing the increased proportion of small Ter119+ differentiated cells derived from Cre+ MEPs compared with Cre− MEPs.

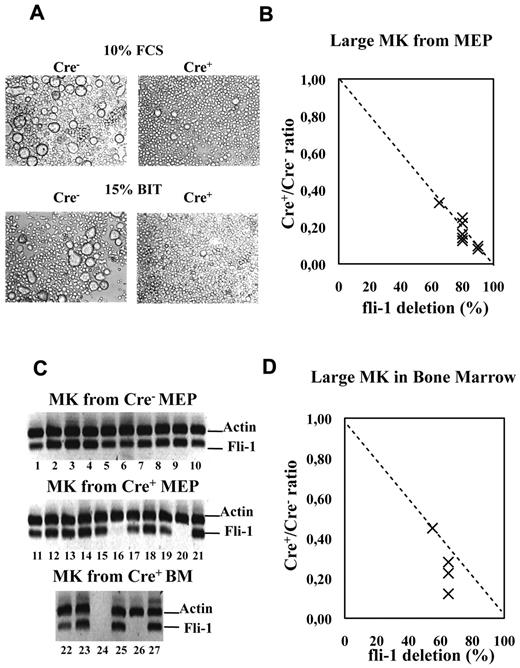

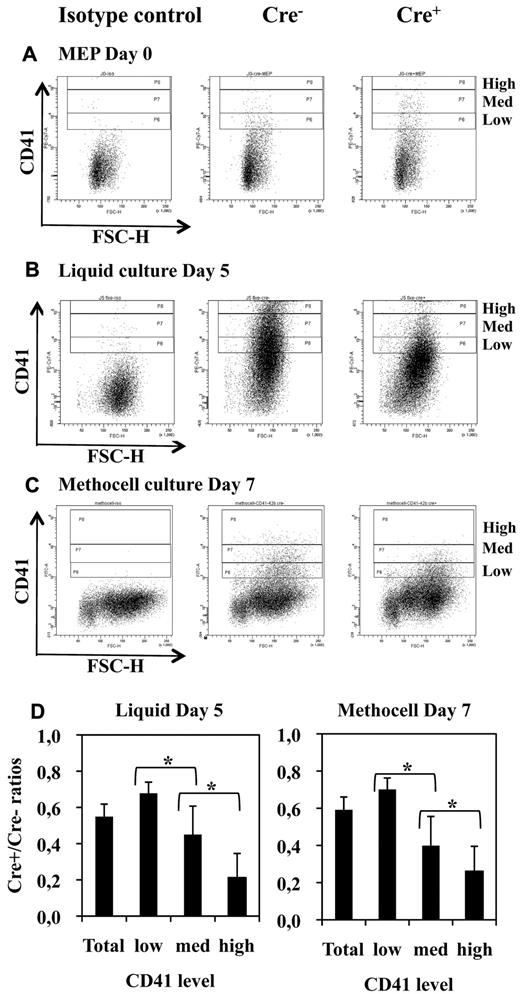

Fli-1 gene deletion drastically reduces the generation of large mature megakaryocytes but does not suppress megakaryocytic commitment

As expected from the results of semisolid colony assays (Figure 3), liquid bulk cultures of Cre+ MEPs displayed a drastic decrease in the number of large mature megakaryocytes (Figure 6A) proportionally to the extent of Fli-1 gene deletion (Figure 6B). Single-cell RT-PCR analyses revealed that most of these few remaining megakaryocytes (9/11) still expressed Fli-1 mRNA, indicating that most of them were derived from undeleted MEP (Figure 6C lanes 11-21). Likewise, we found a drastic reduction in the number of large acetylcholinesterase-positive megakaryocytes present in the bone marrow of injected Cre+ compared with Cre− mice (Figure 6D). Furthermore, single-cell RT-PCR analyses revealed that most of these few remaining large mature megakaryocytes (4/5) still expressed Fli-1 mRNA and thus escaped Fli-1 deletion (Figure 6C lanes 22-27). Contrasting with this drastic effect on megakaryocytes maturation, the number of bone marrow CD41-positive cells were only slightly reduced (Table 1), and their polyploidy was only slightly affected (40% decrease of > 8n cells; supplemental Figure 3). Moreover, sorted double-positive bone marrow CD41+CD61+ cells displayed similar Fli-1 deletion efficiencies compared with the unsorted BMC populations, thus confirming that most of them were produced in the absence of Fli-1 (60% deletion in sorted cells CD41+CD61+ cells compared with 50% or 40% in unsorted BMCs in 2 different experiments, respectively; data not shown). In agreement to these in vivo data, Cre+ MEP displayed a similar 50% decrease in the production of CD41+ cells in both liquid (Figure 7B) and semisolid cultures (Figure 7C). The expression level of CD41 was clearly higher than the expression level in the initial MEPs (Figure 7A), thus confirming true megakaryocytic commitment. In addition, the decrease in the production of CD41+ cells by Cre+ MEPs in both liquid (Figure 7B) and semisolid cultures (Figure 7C) gradually increased with the expression level of CD41 (Figure 7D) and preferentially affected the most mature CD41+CD42b+ cells (supplemental Figure 5). Taken together, these data indicate that Fli-1 becomes increasingly required during the progression of megakaryocytic maturation ending with a critical requirement for the increase in cell size, CD41 and CD42b expression levels, accompanying and immediately following polyploidization.37

Fli-1 gene deletion drastically impairs the production of large mature megakaryocytes. Cre+ or Cre− MEPs have been cultured for 5 days in liquid medium supplemented either with 10% FCS and a complete cocktail of myeloid cytokines or in serum-free medium containing 15% BIT and only cytokines favoring megakaryocytic differentiation. (A) Picture showing the drastic decrease in the number of large megakaryocytes in Cre+ MEP cultures. (B) Dot plot showing the decrease in the number of large mature megakaryocytes in Cre+ versus Cre− MEP cultures according to increasing Fli-1 gene deletion efficiency. Relative numbers of large mature megakaryocytes were determined by counting at least 3 different fields of MGG stained cytospins obtained with equivalent numbers of cells from Cre+ and Cre− MEP cultures (compilation of the results from 4 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice and MEP cultures performed in either FCS containing or serum-free medium). (C) Single-cell RT-PCR analyses showing the proportion of large megakaryocytes still expressing Fli-1 mRNA (undeleted cells) isolated from culture of Cre− MEP (lanes 1-10), from culture of Cre+ MEPs with an initial deletion efficiency of 85% (lanes 11-21) and from bone marrow of injected Cre+ mice displaying deletion efficiency in total BMC population of 55% (lanes 22-27). (D) Dot plot showing the decrease in the number of large mature acetylycholinesterase-positive megakaryocytes counted on BMC cytospins from 4 injected Cre+ mice displaying the indicated Fli-1 gene deletion efficiencies.

Fli-1 gene deletion drastically impairs the production of large mature megakaryocytes. Cre+ or Cre− MEPs have been cultured for 5 days in liquid medium supplemented either with 10% FCS and a complete cocktail of myeloid cytokines or in serum-free medium containing 15% BIT and only cytokines favoring megakaryocytic differentiation. (A) Picture showing the drastic decrease in the number of large megakaryocytes in Cre+ MEP cultures. (B) Dot plot showing the decrease in the number of large mature megakaryocytes in Cre+ versus Cre− MEP cultures according to increasing Fli-1 gene deletion efficiency. Relative numbers of large mature megakaryocytes were determined by counting at least 3 different fields of MGG stained cytospins obtained with equivalent numbers of cells from Cre+ and Cre− MEP cultures (compilation of the results from 4 different couples of Cre+ and Cre− mice and MEP cultures performed in either FCS containing or serum-free medium). (C) Single-cell RT-PCR analyses showing the proportion of large megakaryocytes still expressing Fli-1 mRNA (undeleted cells) isolated from culture of Cre− MEP (lanes 1-10), from culture of Cre+ MEPs with an initial deletion efficiency of 85% (lanes 11-21) and from bone marrow of injected Cre+ mice displaying deletion efficiency in total BMC population of 55% (lanes 22-27). (D) Dot plot showing the decrease in the number of large mature acetylycholinesterase-positive megakaryocytes counted on BMC cytospins from 4 injected Cre+ mice displaying the indicated Fli-1 gene deletion efficiencies.

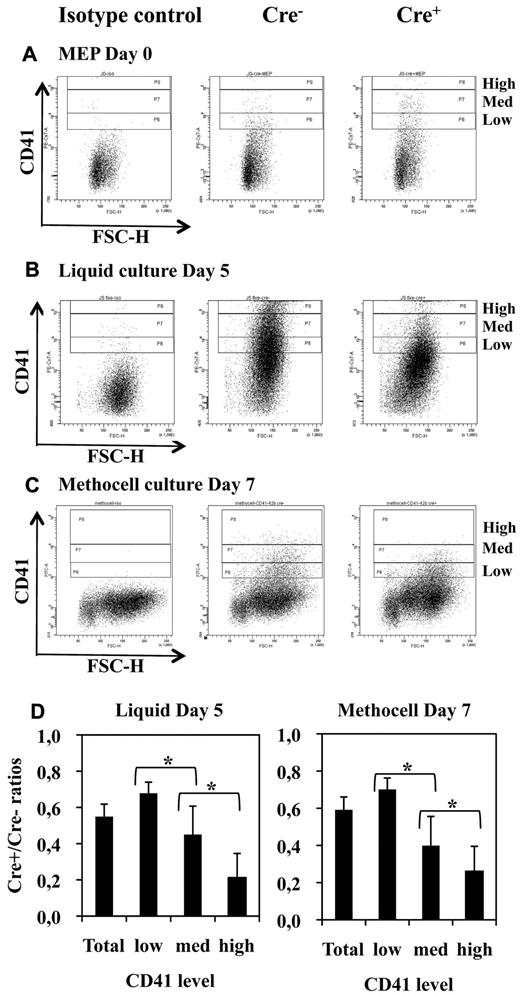

Fli-1 gene deletion does not completely suppress the production of CD41-positive cells but decreases their maturation. (A-C) FACS diagrams showing CD41 expression in freshly purified Cre− and Cre+ MEPs (A) and in their cell progenies taken after 5 days of culture in serum-free liquid medium (B) or after 7 days of culture in semisolid methocell medium (C) both supplemented with a complete cocktail of myeloid cytokines. (D) Histograms showing the progressive decrease in Cre+/Cre− ratios of positive cells numbers according to increasing levels of CD41. Statistically significant differences between Cre+/Cre− ratios are indicated by asterisks. All Cre+/Cre− ratios were significantly different from 1 (n = 5 and n = 4 for liquid and methocell cultures, respectively).

Fli-1 gene deletion does not completely suppress the production of CD41-positive cells but decreases their maturation. (A-C) FACS diagrams showing CD41 expression in freshly purified Cre− and Cre+ MEPs (A) and in their cell progenies taken after 5 days of culture in serum-free liquid medium (B) or after 7 days of culture in semisolid methocell medium (C) both supplemented with a complete cocktail of myeloid cytokines. (D) Histograms showing the progressive decrease in Cre+/Cre− ratios of positive cells numbers according to increasing levels of CD41. Statistically significant differences between Cre+/Cre− ratios are indicated by asterisks. All Cre+/Cre− ratios were significantly different from 1 (n = 5 and n = 4 for liquid and methocell cultures, respectively).

Discussion

In the present study, we used new transgenic mice allowing inducible Fli-1 gene deletion to determine the consequences of Fli-1 loss on adult myelopoiesis. Our results showed that Fli-1 loss modified multiple lineage commitment decisions as well as the proliferation/differentiation balance in the erythrocytic lineage.

At the highest hierarchical level analyzed, Fli-1 loss induced a specific increase in the number of bipotent MEPs. Importantly, this MEP increase did not occur at the expense of the GMP number. Furthermore, this MEP increase occurred without concomitant increase in the overall erythrocytic and megakaryocytic progeny of CMPs that are supposed to generate MEPs and GMPs. These data thus indicate that the increase in MEPs induced by Fli-1 loss did not originate from a commitment switch occurring at the CMP level, but probably rather through the alternative pathway initiated directly at the level of HSCs.3,4,38,39 Similar increase in MEPs has also been observed following inducible deletion of the gene encoding the other ETS transcription factor Spi-1/Pu.140 in adult mice, and this increase is currently at least partly explained by direct interaction and functional cross-antagonism between Spi-1/Pu.1 and Gata-1.41 Although Fli-1 is also a binding partner of Gata-1, available data indicate that Fli-1 cooperates rather than inhibits Gata-1 activity, thus suggesting that Fli-1 most probably repress MEP production through a different mechanism. Interestingly enough, a recent study led strong support for a positive contribution of Notch signaling in the direct generation of MEPs by HSCs.8 Furthermore, activation of Notch signaling in HSCs has also been reported to stimulate the direct production of NK cells.42 In that context, it is worth noting that our present study confirmed that Fli-1 loss also induced a significant increase in NK cells as already observed by others in chimeric Fli-1−/− mice.25 An exciting possibility suggested by our study, that could simultaneously explain both the increase in MEPs and NK cells induced by Fli-1 loss, would be therefore that Fli-1, as already reported for Ikaros,43 might be a negative regulator of Notch signaling in HSCs.

In agreement with previous studies with chimeric Fli-1−/− mice,25 the present study confirmed that Fli-1 loss is also associated with decreased granulopoiesis in adult and further clarified the origin of this decrease. We found indeed that this decreased granulopoiesis was associated with a specific decrease of granulocytic progenitors and symetrical slight increase of monocytic progenitors. Furthermore, while the numbers and the overall clonogenicity of CMPs and GMPs were not affected by Fli-1 loss, both of them generated an increased number of monocytic colonies compensating the decrease in granulocytic colonies. Altogether, these new observations strongly suggest that Fli-1 loss favors the commitment of multipotent and bipotent progenitors toward the monocytic lineage at the expense of the granulocytic lineage. Interestingly, while G-CSF is known to instruct the commitment of bipotent GMPs toward granulocytic differentiation,44 other studies have shown that G-CSF stimulation stabilizes Fli-1 protein.45 Fli-1 can thus be added to the growing list of transcription factors that, like Irf8, Spi-1/Pu.1, Mafb, Cebpϵ, and Gfi1, contribute differentially to the granulocytic versus monocytic commitment of bipotent GMP in response to growth factors.2,46

The most drastic effect of Fli-1 loss was observed at the level of erythrocytic and megakaryocytic lineages. First, we found that Fli-1 loss drastically impaired late stages of megakaryocytic differentiation. This first point was evidenced by a drastic reduction in the number of large mature megakaryocytes present in bone marrow, a drastic reduction of their in vitro production either by total BMCs (CFU-MK) or by purified MEPs, as well as by our finding that the large majority of these few remaining mature megakaryocytes turned out to be undeleted. Furthermore, we found that Fli-1 loss reduced approximately 2-fold megakaryocytic commitment at the benefit of erythrocytic commitment. This second point was evidenced by the increased number of bone marrow BFU-E and most importantly by our finding that MEPs generated the same number of colonies with an increased proportion of erythrocytic versus megakaryocytic cells. Taken together, our results established that, in agreement with its expression profile, Fli-1 slightly favors megakaryocytic commitment at the expense of erythrocytic commitment and becomes increasingly required during late stages of megakaryocytes maturation. Interesting challenges for future studies will be to determine whether this differential requirement of Fli-1 simply reflects stoichiometric variations between different ETS members with completely redundant functions along the megakaryocytic differentiation process or is due to real nonredundant functions among the ETS family in the regulation of specific target genes and/or differential regulation of common target gene as previously suggested by others.26

Lastly, by comparing the proliferation and erythrocytic differentiation of purified Fli-1–deleted and –undeleted MEPs, our study is the first to demonstrate the critical role of Fli-1 in the control of the proliferation/differentiation balance during normal erythropoiesis. Interestingly, this dual property of Fli-1 observed in normal erythropoiesis is quite similar to its role evidenced in erythroleukemic cells.47,48 Moreover, Spi-1/Pu.1 has also been reported to play a similar role in erythroleukemic cells as well as during fetal erythropoiesis,49,50 although its role during normal adult erythropoiesis has not been clearly addressed. An interesting perspective raised by all these data will be to know if this common property of Fli-1 and Spi-1/Pu.1 relies on the deregulation of common targets genes such as genes involved in ribosome biogenesis that we recently identified in erythroleukemic cells.48

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that Fli-1 controls the commitment decisions of several multipotent progenitors during adult hematopoiesis as well as proliferation/differentiation balance during normal erythropoiesis. We believe that our new transgenic mice allowing inducible Fli-1 gene deletion in adult mice should be a useful tool to further investigate the downstream molecular events involved in these new functions of Fli-1.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to W. Reith, D. Aubert, K. Rajewsky, A. de La Coste, M. Rassouzaldegan, and F. Nicolini for providing us with plasmids for the cloning of homologous recombination arms, ES cells clone ENS, Mx1-Cre mice, Sycp1-Cre mice, and recombinant EPO, respectively. We thank also A. Gy and S. Girard for their help in the initial establishment of recombinant ES cells, C. Pondarre for her help in blood cells analyses during the initial characterization of our transgenic mice phenotype, A. Dorier for his help with short-term mice housing during pIpC injections, and W. Vainchenker for helpful discussions. Highly expert assistance of C. Bella and S. Dussurgey at the IFR128 cell sorting platform is also greatly acknowledged.

This work has been supported by grants from the CNRS and Université Lyon 1 and by specific grants from the Ligue contre le Cancer (Labellisation 2005-2007, 2010-2012, and Comité du Rhône). F.M. is a member of Inserm. J.S., B.G., C.G., M.W.G., and J.M.V. are members of the CNRS.

Authorship

Contribution: J.S., M.W.-G., and C.G. performed most of the experiments, interpreted the data, and assisted with the writing of the paper; B.G. performed cytological analyses of bone marrow megakaryocytes and assisted with initial FACS analyses and writing of the paper; J.-M.V. performed ES cell injections for the generation of founder mice and managed most of the mice crosses; and J.S. and F.M. designed the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: François Morlé, CNRS UMR5534, Centre de Génétique Moléculaire et Cellulaire, 16 rue Dubois, Université Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, F-69622, France; e-mail: francois.morle@univ-lyon1.fr.