Abstract

We have adapted the corn-trypsin inhibitor whole-blood model to include EA.hy926 as an endothelium surrogate to evaluate the vascular modulation of blood coagulation initiated by relipidated recombinant tissue factor (rTf) and a cellular Tf surrogate, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated THP1 cells (LPS-THP-1). Compared with bare tubes, EA.hy926 with rTf decreased the rate of thrombin formation, ITS accumulation, and the production of fibrinopeptide A. These phenomena occurred with increased rates of factor Va (fVa) inactivation by cleavages at R506 and R306. Thus, EA.hy926 provides thrombin-dependent protein C activation and APC fVa inactivation. Comparisons of rTf with LPS-THP-1 showed that the latter gave reduced rates for TAT formation but equivalent fibrinopeptide A, and fV activation/inactivation. In the presence of EA.hy926, the reverse was obtained; with the surrogate endothelium and LPS-THP-1 the rates of TAT generation, fibrinopeptide release, and fV activation were almost doubled, whereas cleavage at R306 was equivalent. These observations suggest cooperativity between the 2 cell surrogates. These data suggest that the use of these 2 cell lines provides a reproducible quasi-endothelial quasi-inflammatory cytokine-stimulated monocyte system that provides a method to evaluate the variations in blood phenotype against the background of stable inflammatory cell activator and a stable vascular endothelial surrogate.

Introduction

Virchow postulated 3 phenomena that lead to venous thrombosis: (1) the components contained within the blood itself lead to systemic hypercoagulability; (2) alteration of the endothelium from injury or dysfunction; and (3) alterations of blood flow.1 These postulates are the foundation for the physiologic understanding of blood coagulation and the maintenance of the hemostatic balance in the venous circulation.

The maintenance of blood fluidity and vascular integrity is actively maintained by collaborations between the vascular wall and the procoagulant and anticoagulant functions in blood. Cell-bound and soluble constituents cooperate to maintain this quasi-equilibrium fluid state. Upon vascular perforation, multiple interactions initiate a local coagulant response, promoting platelet adhesion/aggregation, the generation of membrane-bound catalysts, thrombin generation, and fibrin deposition that overcome local anticoagulants. These processes arrest blood loss with dimensions relevant to the injury. Subsequently, fibrinolysis and cellular proliferation repair2 the injured tissue.

The coagulation processes have been studied in vitro using anticoagulated phlebotomy blood,3 derived plasma,4,5 isolated component systems,6-8 and numerical simulations.9,10 We have used corn-trypsin inhibitor (CTI) stabilized whole blood to study the tissue factor (Tf)–initiated process in the absence of chelating anticoagulants.11,12 Several hundred of these experiments have been performed to characterize the temporal dynamics of various blood clotting reactions in healthy persons, congenital abnormalities, and pharmacologic interventions.11-14 In the “normal” population, extreme phenotypic variations (> 5-fold) in Tf-initiated thrombin generation have been observed.15

To evaluate the contributions of the vascular wall to the blood coagulation process, studies have used excised blood vessels16-18 and isolated cells.19-21 Badimon22 used human phlebotomy blood in a flow chamber with denuded swine vessels. Although this model is more physiologic in nature, these vessels may vary in protein expression between donor animals and are also complicated by xeno-protein associations.23 We and others have used isolated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs),19 human umbilical artery endothelium,20 and human cerebral microvascular endothelium.21 All these cells display altered behavior and phenotype when removed from their natural environment,24 depending upon basement membrane composition,25,26 and show altered protein expression with passage.27 Consequently, thrombomodulin (TM) and von Willebrand factor (VWF) have been shown to vary considerably in isolated HUVECs.28 To address this variability, investigators have used EA.hy926 cells, an immortalized cell line produced by hybridization of HUVECs with lung carcinoma cell A549, to produce cells that display consistent endothelial cell markers over prolonged passages.29,30 EA.hy926 cells are reported to “maintain identical characteristic during at least 100 passages” and express many endothelial proteins.31 EA.hy926 is the most studied and characterized permanent human vascular endothelial cell line.32 Based on these reports, we have evaluated EA.hy926 as a surrogate “endothelium” to explore how the blood coagulation system is modulated by a confluent cellular provider of vascular regulatory elements.

The sources, expression, and regulation of natural Tf by cells and their influence upon blood coagulation processes have been controversial.33-37 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated monocytes that express Tf,38,39 have been used.40,41 However, Tf expression on natural monocytes is highly variable.40-42 LPS-stimulated THP1 cells appear to potentially provide a stable surrogate representing an inflammatory peripheral blood cell source of Tf.

In the present study, we explore the use of EA.hy926 and LPS-stimulated THP1 cells (LPS-THP-1 cells) as surrogates for human endothelial cells and cytokine activated monocytes in a closed system for the simulation of events that might occur during venous stasis. This approach provides a reproducible model that incorporates the components of Virchow's triad necessary for study of cellular regulation of Tf-initiated coagulation in blood. Furthermore, this approach limits the phenotypic variability in blood coagulation observed for the normal population to that of the human donor.15,43

Methods

Materials

Mouse monoclonal anti–human Tf pathway inhibitor (TFPI) antibody (clone no. AHTFPI-5138), sheep polyclonal anti–human TFPI (no. PAHTFPI-S) and goat anti–human VWF (no. PAHVWF-G) antibodies were gifts from Dr R. Jenny (Haematologic Technologies Inc). Monoclonal antibody anti-TM (product no 2375; American Diagnostica). Mouse anti–human VWF-99, anti–Tf-5, anti–Tf-48, anti–TM-41, anti–fVa-17, and α1-Fbg monoclonal and burro polyclonal monospecific anti–prethrombin 1 antibodies were produced and characterized in house.37,44,45 Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–labeled secondary antibodies were purchased from Southern Biotechnology Associates. Anti-burro (goat anti–equine HRP, no. 6040-05) HRP-labeled secondary antibodies were purchased from Southern Biotechnology Associates. Gel electrophoresis standards were from Novagen. The antibodies used for confocal studies (primary immunoglobulin G antibodies, anti-TM mouse clone [Lab Vision], anti–endothelial cell protein C receptor [EPCR] goat [R&D Systems], and anti-VWF rabbit clone no. A0082 [DAKO] and secondary antibodies, donkey anti–rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 [Invitrogen], donkey anti–goat Alexa Fluor 555 [Invitrogen], and donkey anti–mouse Alexa Fluor 647 [Invitrogen]) were all gifts from Dr Edwin G. Bovill (University of Vermont). Western Lightning Plus ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence substrate; PerkinElmer). Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium with Glutamax, Alexa Fluor 488, and Alexa Fluor 633 was purchased from Invitrogen. Anti–Tf-5 for confocal microscopy was bound to R-phycoerythrin via a LNK023RPE kit from AbD (Serotec). Millipore polyvinylidene difluoride membrane Immobilon-FL, nitrocellulose, VectorShield with 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole, gentamicin, soluble human recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and all other reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific.

EA.hy926, the endothelial-like hybridoma cells, were a gift from Dr C. J. Edgell (University of North Carolina). HUVECs no. HUVEC-001F-M, fresh HUVEC basal medium no. HUVEC-002, and HUVEC stimulatory supplement no. HUVEC-004 were purchased from AllCells. RPMI 1640 and THP1 monocytic cells were obtained from ATCC. Recombinant Tf1-243 (rTf), a gift from Dr R. Lundblad and Dr S. L. Liu (Hyland Division; Baxter Healthcare), was relipidated in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidyl serine (PS) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (PC) at 25% PS/75% PC (PCPS).46 PC and PS were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. TFPI was a gift from Dr S. Hardy (Chiron). Goat anti-mouse HRP-labeled secondary antibody (no. A9917), β-mercaptoethanol, benzamidine-HCl, tris-HCl, HEPES, trifluoroacetic acid, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA), and LPS from Escherichia coli EH100 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. CTI was prepared in house.11 Fetal bovine serum (FBS premium) was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals. Thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) ELISA kits were from Siemens. U-bottom BD Falcon plates were (BD Labware). EPCR immunoassay kits were obtained from R&D Systems. Citrated plasma for clotting assays was produced in house (10 donors).

Subjects

Healthy male donors between the ages of 23 years and 35 years (mean 27 years ± 5 years, n = 5) were recruited and advised according to a protocol approved by the University of Vermont Human Studies Committee. Written consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Subject questionnaires showed no clinical history of coagulopathy nor aspirin or drug use. Repeat blood draws were performed from this donor population.

EA.hy926 adherence and growth in polystyrene reaction tubes

Polystyrene tubes and polypropylene caps11 were treated with a Harrick PDC-3XG plasma cleaner (high setting 20 minutes ambient air). Confluent EA.hy926 cells from two 10-cm diameter culture plates were resuspended in 100 mL growth medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with Glutamax, gentamicin, and 10% FBS premium), and distributed in 2-mL aliquots to the prepared capped polystyrene tubes. Two days growth in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator allowed the cells to adequately divide and adhere to achieve confluence in the bottom half of the horizontal tube cylinder (verified under bright-field microscopy). Endothelial growth medium was replaced with growth medium with no FBS at the end of the second day, and the cells were incubated for an additional 15 hours to attain quiescence. The “endothelium” lined tubes were used in whole-blood experiments on the third day after removal of the medium and one wash with fresh medium. The unilaminar “endothelium” from 5 random tubes was removed with versene, centrifuged, resuspended in HBS, stained with trypan blue, and counted (5.2 ± 0.2 × 105 cells/tube, n = 5) using a hemocytometer.

Characterization of EA.hy926 cells

Confluent EA.hy926 cells were labeled with preconjugated anti–VWF-99 Alexa Fluor 488 or primary conjugated anti–TM-41 biotin antibody and secondary streptavidin 633. Confocal comparative analyses between EA.hy926 cells and HUVECs for VWF, TM, and EPCR was accomplished using primary and secondary antibodies provided by Dr Edwin G. Bovill as well as a modified microscopy protocol from Dr Bovill and Dr Taatjes.47,48 Briefly, cells were grown to confluence on 8 chambered slides according to cell-type instructions. Cells were rinsed 3 times with 1X Hanks balanced salt solution (HBS) 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM Nacl and fixed for 5 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde (10% formalin) in 1X HBS buffer. Cells were rinsed 3 times in 1X HBS before blocking with preimmune donkey serum for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies TM, EPCR, and VWF were administered for an overnight incubation at 4°C. Secondary antibodies were incubated 1 hour at room temperature. A secondary control incubation including all secondary antibodies in a well containing confluent EA.hy926 and another containing HUVECs showed no immunofluorescence labeling as previously reported for this system when used for blood vessels.47 All images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss MicroImaging) with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil-immersion objective. Excitation was performed using a 405-nm laser diode, 488 argon laser, and 543/633 helium/neon laser, and emissions passed through LP650, BP420-480, BP505-530, and BP560-615 filters to acquire images in 12-bit multitrack mode.

For Tf activity assessment,49 cells were grown to confluence, stimulated for 4 hours with LPS (250 ng/mL LPS-THP-1) or treated with versene, counted, centrifuged (200g for 5 minutes) and resuspended in HBS to a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. These cells were added to citrated plasma containing 0.1 mg/mL CTI and 50 μM PCPS. Plasma clotting was initiated with 25 mM CaCl2. Clotting times were determined using the ST8 clotting instrument (Diagnostica Stago).

For analyses of protein expression, cells were grown to confluence, released from the plate with versene, counted, centrifuged (200g for 5 minutes) and resuspended/lysed in 1% Triton X–100/PBS, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM benzamidine hydrochloride, 200 μM phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride, 40 μM FPRck, 65 kIU aprotinin, 0.5 μg/mL leupeptin, and 0.7 μg/mL pepstatin A. The lysates were mixed, centrifuged at 14 000g, and the supernatants characterized by immunoassays for VWF,45 Tf,37 TM, EPCR, and TFPI. TM was quantitated with anti-TM monoclonal antibody (25 μg/mL; American Diagnostica) coupled beads and probed with biotinylated anti–TM-41 monoclonal antibodies (10 μg/mL) via fluorescence Luminex immunoassay (Luminex Technology).37 Binding was detected with phycoerythrin-streptavidin (5 μg/mL). A nonspecific isotype-matched monoclonal antibody control was included in the reaction mixture. TFPI was quantitated by a sandwich ELISA using anti-TFPI monoclonal antibodies (5 μg/mL) as the capture antibody and a sheep anti-human TFPI antibody (10 μg/mL) as the probe. Binding was detected with HRP-rabbit anti-sheep antibody (1:2000). The EPCR assay was conducted using the R&D Systems protocol.

THP1 cells were treated at a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 with LPS (250 ng/mL, 4 hours).49,50 Cell-surface and total Tf was quantitated via immunoassay.37 TFPI was quantitated by ELISA.

LPS-THP-1 were titrated into CTI phlebotomy blood with clotting times determined visually (2 observers by subjective evaluation). The clotting activity for 2 × 104 stimulated monocytes/mL was determined to be equivalent to 5 pM rTf/PCPS activity and used for all THP1 cell–based Tf experiments.

Phlebotomy blood experiments

The contributions of EA.hy926 and LPS-THP-1 cells to blood coagulation were evaluated by comparing phlebotomy blood 1) in the presence and absence (bare tubes) of EA.hy926 with 5 pM rTf/PCPS, and 2) in the presence and absence of EA.hy926 with 2 × 104 LPS-THP-1 cells as a source of Tf. Donor blood (1 mL) was delivered into tubes containing CTI (100 μg/mL) and a source of Tf as previously described.11 After LPS prestimulation, THP1 cells were added after 1 rinse in HBS, recentrifugation (200g for 5 minutes) and resuspension in HBS (5 × 106 THP1 cells/mL) in 4-μL aliquots (2 × 104 per aliquot). Tubes (37°C) were rocked (16 cycles per minute) and quenched at various time points over the course of 20 minutes with a cocktail of inhibitors: HBS (1 mL total) containing 50 mM EDTA, 20 mM benzamidine-HCl, and 50 μM FPRck. The zero time point contained the inhibitors before the addition of blood. Clot time was established visually by observation of a thickening of the blood in rocked tubes illustrated by a change in the edge of the fluid cycling back and forth from concave to convex. This methods accuracy is best judged by examination of the interception of the “initiation” and “propagation” phases of the reactions (see Figures 2,Figure 3,Figure 4,Figure 5–6) that, in general, correspond to the clot times shown for the present experiments and for the previous more than 400 whole-blood experiments done in this laboratory.6,11-14 A control tube with no Tf was used for each experiment. Controls with no EA.hy926 cells clotted over 20 minutes and with EA.hy926 cells clotted over 17 minutes.

The “initiation” and “propagation” phases have been defined and used by this laboratory since approximately 19946 to describe synthetic coagulation proteome and whole-blood experiments in multiple reports11-14 and reviews.51,52 The “initiation” phase corresponds to the initial time course of TAT accumulation (∼ 2 nM) in which the membrane catalyst elements are formed and assembled. The “propagation” phase corresponds to the major thrombin generation/TAT accumulation (∼ 500 nM-800 nM).

Analyses of whole-blood samples

The quenched samples were centrifuged (15 minutes at 1160g) to separate the clot material from the solution phase. These phases were stored separately at −80°C for further analysis. Samples were analyzed for TAT by ELISA.11 Fibrinopeptide A (FPA) using HPLC methodology53 and with Western blotting for prothrombin, fV, fVa, fVa307-506, and fibrinogen-fibrin reaction products under either nonreducing or reducing conditions.11,54 Densitometry was performed using the Fujifilm chemiluminescent imager LAS4000 and Fujifilm MultiGauge imaging software (ver 3.x). Concentrations were determined from serial dilutions of the relevant purified proteins, the absolute concentration for fV was estimated by normalizing the data assuming a mean physiologic value of 20 nM.55 Fibrinopeptide data were normalized from each subject's control data.

Statistical analyses

All data in the manuscript and figures were expressed as mean (± SEM). Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software) was used to perform variable slope curve fitting analyses, linear analyses, and statistical tests: t test, and ANOVA (repeated measures) with Bonferroni posttest. Differences with values for P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

EA.hy926 cells

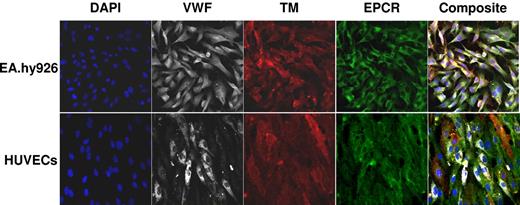

Confocal microscopy showed the presence of TM, EPCR, and VWF on EA.hy926 cells and HUVECs (Figure 1). Tf was not detectable after LPS stimulation (250 ng/mL, 4 hours) either by immunoassay at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells/mL or by activity at 1 × 106 cells/mL (< 10 fM).35,49 Following TNF-α stimulation (10 ng/mL, 4 hours), Tf expression above background was observed via immunoassay but at concentrations below the quantitation limit (0.49 pM per 5 × 105 EA.hy926 cells/mL). The molar concentrations of EA.hy926 expressed TM, VWF, EPCR, and TFPI were determined by immunoassay. These results (Table 1) are similar to those previously published for HUVECs.56-58

Fluorescent confocal micrographs of HUVECs and EA.hy926 hybridoma cells. All images were obtained at a magnification ×400 using a 40X oil immersion objective under identical settings for focus and image capture. EPCR (green), VWF (white), TM (red), and 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) are shown in split xy along with a merged image (composite) as viewed by Zeiss LSM 5 image viewer software.

Fluorescent confocal micrographs of HUVECs and EA.hy926 hybridoma cells. All images were obtained at a magnification ×400 using a 40X oil immersion objective under identical settings for focus and image capture. EPCR (green), VWF (white), TM (red), and 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) are shown in split xy along with a merged image (composite) as viewed by Zeiss LSM 5 image viewer software.

The Tf issue on endothelial cells is controversial. Several recent reviews59-61 document the current understanding of Tf including cell types and anatomical locations. Tf has been reported by several studies to be present on endothelium in vitro,62-65 yet conclusive proof of endothelium Tf synthesis is lacking.66-68 A study of TNF-α–activated HUVECs69 suggests 1 fM/cm2 or a 20 pM concentration (Table 1).

Recombinant Tf with EA.hy926 cells

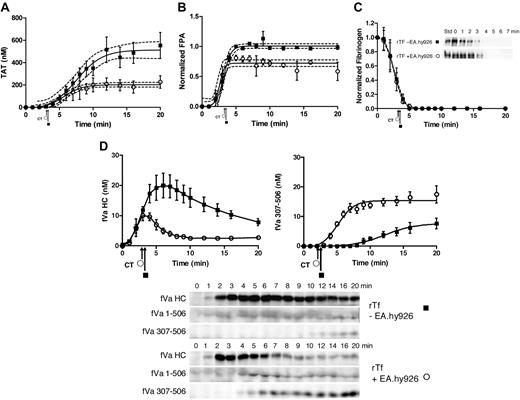

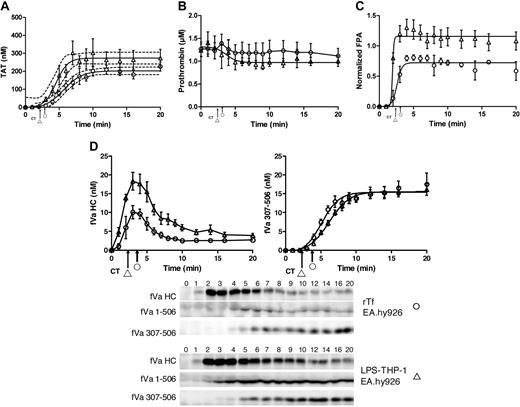

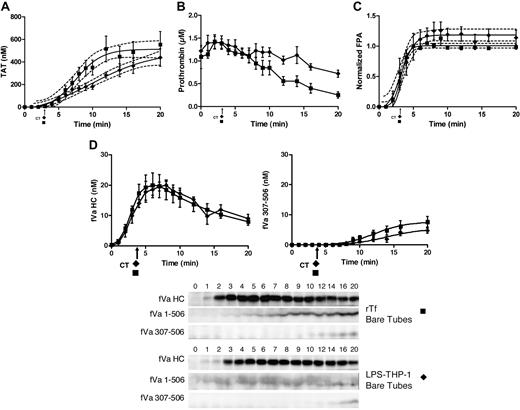

When blood (5 donors) was treated with 5 pM rTf/PCPS in the presence and absence of EA.hy926, the clot time did not vary significantly (2.9 ± 0.14 minutes vs 3.0 ± 0.17 minutes, P = .71). Thrombin generation (TAT formation) in response to 5 pM rTf/PCPS stimulus with or without EA.hy926 is shown in Figure 2A as the mean of 5 experiments (± SEM). Consistent with the visually observed clot time (Figure 2A arrows), the initiation phase of thrombin generation (∼ 2 nM thrombin) is not changed by EA.hy926. Thus the contribution of EA.hy926 TFPI (Table 1) was negligible, as would be anticipated from previous studies.54 In addition, computer modeling9,10,70 predicted only a 16-second increase in the initiation phase duration (data not shown). In contrast, EA.hy926 shortens the duration of the propagation phase (8.9 minutes to 5.2 minutes), decreases the maximum rate of thrombin generation (60 ± 5.5 nM/min to 34 ± 6.6 nM/min, P = .019), and produces less total thrombin (512 ± 28 nM to 203 ± 12 nM, P < .001). The decrease in the rate of thrombin generation during the propagation phase in the presence of EA.hy926 is similar to that previously observed for the purified proteome with soluble TM7 and for HUVEC19 with products corresponding to R507-709 and R307-506,71 which most likely are attributed to the generation of activated protein C (APC) by thrombin with EA.hy926 TM and EPCR (Figure 1).72

rTf-activated CTI-inhibited blood with or without EA.hy926 cells. Bare tubes (■) and tubes containing a unilaminar layer of EA.hy926 (○) were used to measure (A) TAT formation over time after CTI-inhibited fresh blood activation with 5 pM rTf, (B) FPA production, (C) normalized fibrinogen consumption with a representative Western blot of a single subject and (D) fVa generation (left) and inactivation (right) as quantified by densitometry of Western blot analysis using α-fV no. 17 HC antibody showing fVa HC and fVa307-506 HC cleavage product (bottom). FVa1-506 HC cleavage is also shown but was not quantified. Clot times in all experiments are indicated (■ = 3.0 ± 0.17 minutes and ○ = 2.9 ± 0.14 minutes). Dashed line in a and b represents 95% confidence limits.

rTf-activated CTI-inhibited blood with or without EA.hy926 cells. Bare tubes (■) and tubes containing a unilaminar layer of EA.hy926 (○) were used to measure (A) TAT formation over time after CTI-inhibited fresh blood activation with 5 pM rTf, (B) FPA production, (C) normalized fibrinogen consumption with a representative Western blot of a single subject and (D) fVa generation (left) and inactivation (right) as quantified by densitometry of Western blot analysis using α-fV no. 17 HC antibody showing fVa HC and fVa307-506 HC cleavage product (bottom). FVa1-506 HC cleavage is also shown but was not quantified. Clot times in all experiments are indicated (■ = 3.0 ± 0.17 minutes and ○ = 2.9 ± 0.14 minutes). Dashed line in a and b represents 95% confidence limits.

Figure 2B illustrates the normalized FPA generation with rTf in bare tubes compared with EA.hy926. The initial rates of FPA generation in both circumstances are similar (5.1 ± 1.3 μM/min vs 4.2 ± 0.9 μM/min); however, the ultimate relative FPA release is somewhat reduced in the presence of the endothelial cell surrogate, consistent with the earlier termination of thrombin generation (Figure 2A). As observed in Figure 2C and in earlier studies,12 at clot time, virtually all fibrinogen products are removed from the fluid phase of the blood indicating that the initial clot is a heterogeneous mixture of fibrin 1, fibrin 2, and fibrinogen because at clot time only 30% to 40% of total FPA is released (Figure 2B).53

Western blot analyses for prothrombin consumption with rTf with and without EA.hy926 after 5 pM rTf/PCPS stimulation showed that in the absence of EA.hy926 the rate of prothrombin consumption is greater (−0.07 ± 0.01 μM/min) compared with the reaction with EA.hy926 (0.00 ± 0.02 μM/min, P = .003; linear analysis) from time points 6 to 20 minutes. A 20-minute time point comparison shows a greater remaining prothrombin concentration of 1.12 ± 0.17μM in the presence of EA.hy926 versus 0.25 ± 0.07μM (P = .002) without EA.hy926 (data not shown).

Western blot analyses of the fV activation/inactivation process in 5 pM rTf/PCPS initiated reactions in the presence and absence of EA.hy926 are shown in Figure 2D. In both cases, fVa heavy chain (HC) is observed by 1 minute. Densitometric analyses (n = 5) shows that although the initial rate of fV activation is not different (with or without EA.hy926 cells, 4.7 ± 0.7 nM/min vs 4.5 ± 1.4 nM/min; Figure 2d). With EA.hy926, a 2-fold decrease in the maximum level of fVa HC is observed (20 vs 10 nM, P < .001). As expected,71 inactivation of fVa via the R506 cleavage occurs more rapidly in the presence of EA.hy926 (5.2 ± 0.8 minutes vs 7.6 ± 0.9 minutes) and the initial rate of the fVa R307-506 cleavage product formation is accelerated (2.9 ± 0.44 nM/min vs 0.57 ± 0.13 nM/min; P < .001). With EA.hy926, the 30-kDa fVai fragment, fVa307-506 is seen earlier (4.0 ± 0.7 minutes vs 9.2 ± 0.8 minutes) consistent with the functional contribution of the EA.hy926 provided TM and EPCR (Table 1)71-73 to the APC R306, R506 cleavages.

Recombinant Tf versus LPS-THP-1 in bare tubes

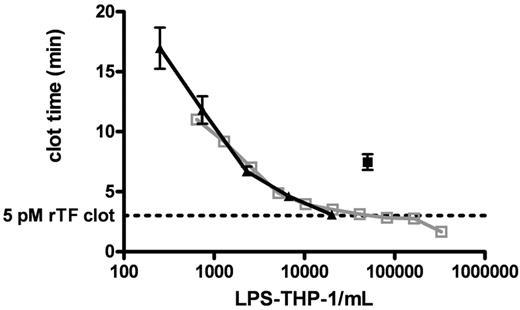

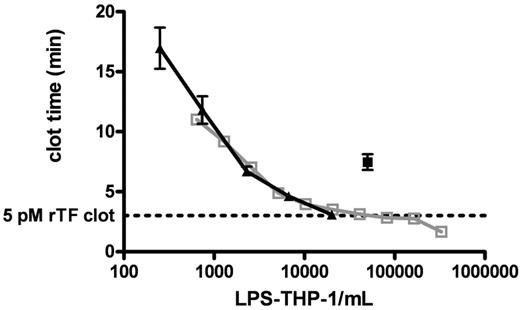

Figure 3 shows clot times for 2 titrations (from 644 to 3.3 × 105 cells/mL and from 250 to 2.0 × 104 cells/mL) of LPS-THP-1 (LPS stimulated at 250 ng/mL, 4 hours) into CTI-inhibited blood. These experiments demonstrate the reproducibility of LPS-induced Tf activity by THP1 cells. LPS-THP-1 (2 × 104 cells/mL) yield equivalent clotting times (3.1 ± 0.1 minutes) to that of 5 pM rTf/PCPS (Figure 3 dashed line). The concentration of surface Tf antigen per 2 × 104 LPS-THP-1 cells/mL was found to be 250 fM; a value similar to that previously reported.37

Clotting of CTI-inhibited fresh blood triggered with LPS-THP-1. CTI-inhibited whole blood was triggered to clot by varying concentrations of LPS-THP-1 (▴, n = 5 blood donors). A total of 2 × 104 LPS-THP-1 cells/mL are shown to have equivalent clotting activity to the 5pM rTf). Clot time represented by the horizontal dashed line (n = 5). An experiment using another population of titrated LPS-THP-1 cells illustrates a very similar titration curve indicating reproducibility of LPS-THP-1 activity (open gray box, n = 1 donor). A total of 5 × 104 nonstimulated THP1 cells/mL (■, n = 5 donor) is equivalent in clotting activity to 2.5 × 103 stimulated THP1 cells/mL. Nonstimulated THP1 cells show 5% of stimulated THP1 activity.

Clotting of CTI-inhibited fresh blood triggered with LPS-THP-1. CTI-inhibited whole blood was triggered to clot by varying concentrations of LPS-THP-1 (▴, n = 5 blood donors). A total of 2 × 104 LPS-THP-1 cells/mL are shown to have equivalent clotting activity to the 5pM rTf). Clot time represented by the horizontal dashed line (n = 5). An experiment using another population of titrated LPS-THP-1 cells illustrates a very similar titration curve indicating reproducibility of LPS-THP-1 activity (open gray box, n = 1 donor). A total of 5 × 104 nonstimulated THP1 cells/mL (■, n = 5 donor) is equivalent in clotting activity to 2.5 × 103 stimulated THP1 cells/mL. Nonstimulated THP1 cells show 5% of stimulated THP1 activity.

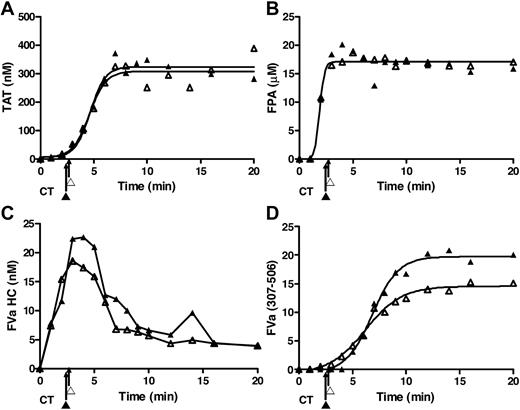

LPS-THP-1 (2 × 104 cells/mL) and 5 pM rTf/PCPS with CTI blood in the absence of EA.hy926 showed no difference in clot time (3.0 ± 0.34 minutes vs 3.0 ± 0.17 minutes, P = 1.0). Although both Tf sources yield similar visual clotting times (Figure 4A arrow) and initiation phase durations (Figure 4A), the TAT accumulation profiles show some variation. The maximum rate of thrombin generation is decreased by 2.3-fold when LPS-THP-1 cells are substituted for rTf (60 ± 5.5 nM/min to 26 ± 2.8 nM/min, P < .001). Furthermore, although the maximum concentration of TAT at 20 minutes is not significantly different in LPS-THP-1–activated blood, TAT generation had not achieved a plateau value at the termination of the experiment. The rTf stimulated prothrombin consumption (time points 6-20 minutes; Figure 4B) occurs at a faster rate (−0.07 ± 0.01 μM/min) than with LPS-THP-1 (−0.03 ± 0.01 μM/min, P = .016). Normalized FPA generation in blood activated with either Tf source is similar (Figure 4C).

CTI-inhibited fresh blood activated with rTf or LPS-THP-1 in the absence of EA.hy926. Bare tubes containing rTf (■) or LPS-THP-1 (♦) activated whole blood was used to measure (A) TAT formation over time, (B) prothrombin consumption, (C) FPA production, and (D) fVa generation (left), inactivation (right), and representative Western blot. FVa1-506 HC cleavage is also shown but was not quantified. Clot times in all experiments are indicated (■ = 3.0 ± 0.17 minutes and ♦ = 3.0 ± 0.34 minutes). Dashed line in panels A and C represents 95% confidence limits.

CTI-inhibited fresh blood activated with rTf or LPS-THP-1 in the absence of EA.hy926. Bare tubes containing rTf (■) or LPS-THP-1 (♦) activated whole blood was used to measure (A) TAT formation over time, (B) prothrombin consumption, (C) FPA production, and (D) fVa generation (left), inactivation (right), and representative Western blot. FVa1-506 HC cleavage is also shown but was not quantified. Clot times in all experiments are indicated (■ = 3.0 ± 0.17 minutes and ♦ = 3.0 ± 0.34 minutes). Dashed line in panels A and C represents 95% confidence limits.

The rate of fV activation was equivalent with either 5 pM rTf/PCPS and LPS-THP-1 (4.7 ± 0.7 nM/min, 4.3 ± 0.6 nM/min, P = .70; Figure 4D). However, with rTf/PCPS, the formation of fVa307-506 was slightly accelerated relative to LPS-THP-1 (0.57 ± 0.13 nM/min vs 0.39 ± 0.06 nM/min, P < .001) possibly because of the influence of the added PCPS in the former because cleavage at R306 is PCPS dependent.74

EA.hy926 with LPS-THP-1 or rTf

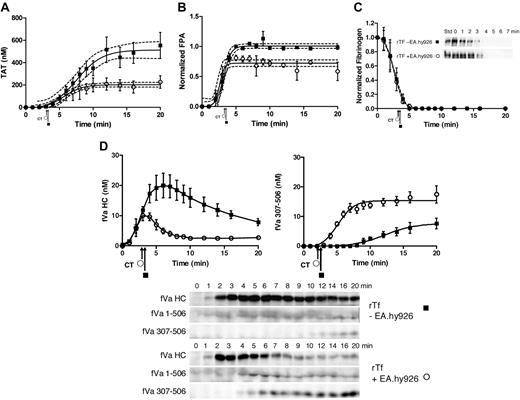

In the presence of EA.hy926, LPS-THP-1 blood clotted slightly more rapidly than rTf activated blood (2.3 ± 0.10 minutes vs 2.9 ± 0.14 minutes, P = .01).

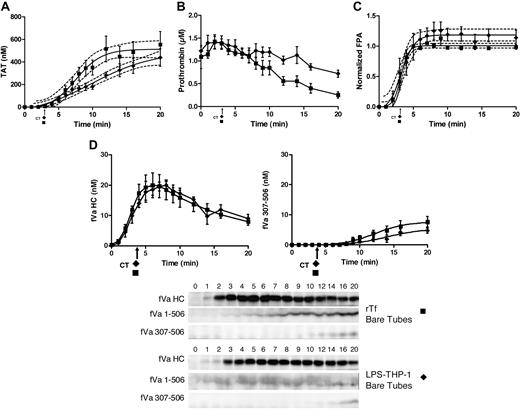

In the presence of EA.hy926, blood activated with LPS-THP-1 (2 × 104 cells/mL) shows a trend toward an accelerated rate of TAT accumulation (63 ± 15 nM/min) compared with 5 pM rTf/PCPS (34 ± 6.6 nM/min, P = .047; Figure 5A). The maximum thrombin accumulated is also slightly greater for the LPS-THP-1 reactions compared with rTf/PCPS reactions (281 ± 52 nM vs 203 ± 12 nM, respectively). In contrast, compared with bare tubes (Figure 4A), the presence of EA.hy926 (Figure 5A) with LPS-THP-1 increased the maximum rate of TAT generation from 26 ± 2.8 nM/min to 63 ± 15 nM/min, P = .008) and shortens the duration of the propagation phase (> 17 to ∼ 7 minutes). With EA.hy926, TAT formation is unchanged from time points 7 to 20 minutes (Figure 5A), whereas a slower continued TAT generation occurred without EA.hy926 (rate, 26 ± 2.8 nM/min, P < .001; Figure 4A). In the absence of EA.hy926, slower thrombin generation continued beyond 15 minutes such that at the 20-minute point, TAT concentrations are not statistically different (without EA.hy926, 439 ± 87 nM;with EA.hy926, 281 ± 52 nM, P = .26; Figure 4A).

CTI-inhibited fresh blood activated with rTf or LPS-THP-1 in the presence EA.hy926. Tubes containing a unilaminar layer of EA.hy926 with rTf (○) or LPS-THP-1 (▵) activated whole blood were used to measure (A) TAT formation, (B) prothrombin consumption, (C) FPA production, and (D) fVa generation (left), inactivation (right), and representative Western blot. FVa1-506 HC cleavage is shown but not quantified. Clot times in all experiments are indicated (▵ = 2.3 ± 0.10 minutes and ○ = 2.9 ± 0.14 minutes). Dashed line in a and c represents 95% confidence limits.

CTI-inhibited fresh blood activated with rTf or LPS-THP-1 in the presence EA.hy926. Tubes containing a unilaminar layer of EA.hy926 with rTf (○) or LPS-THP-1 (▵) activated whole blood were used to measure (A) TAT formation, (B) prothrombin consumption, (C) FPA production, and (D) fVa generation (left), inactivation (right), and representative Western blot. FVa1-506 HC cleavage is shown but not quantified. Clot times in all experiments are indicated (▵ = 2.3 ± 0.10 minutes and ○ = 2.9 ± 0.14 minutes). Dashed line in a and c represents 95% confidence limits.

In the presence of EA.hy926, with rTf or LPS-THP-1 activation, the rates of prothrombin consumption are not significantly different but the trend to faster consumption is in favor of LPS-THP-1 (Figure 5B).

The rate of FPA generation was accelerated in the presence of EA.hy926 when blood was activated with LPS-THP-1 compared with rTf (Figure 5C). An increased rate of FPA release (9.3 ± 0.9 μM/min vs 4.2 ± 0.9 μM/min, P = .001) with an earlier point for FPA detection (2 vs 3 minutes) was evident consistent with the accelerated clot time observed for the EA.hy926 system after LPS-THP-1 activation. In bare tubes, both Tf sources produced FPA to the same ultimate level at similar rates (Figure 4C).

Densitometric analyses of fibrinogen-fibrin blots, in the presence or absence of EA.hy926, showed no significant difference in the rate of fibrinogen removal as expected from the similar clot times with THP1 activation in the presence of EA.hy926 (data not shown).

In the presence of EA.hy926, activation with either Tf source did not significantly alter the maximum rates of fVa generation (rTf/PCPS, 4.5 ± 1.4 nM/min; LPS-THP-1, 6.4 ± 0.6 nM/min, P = .18); however, a lag was seen with rTf (Figure 5D). Under the experimental conditions used, the initial inactivation of fVa (R506) associated with rTf/PCPS stimulation with EA.hy926 allowed only 3 time points, limiting the power of the analysis. In the presence of EA.hy926, 5 pM rTf/PCPS caused slightly accelerated formation of fVai307-506 over the LPS-THP-1–activated process (rTf/PCPS, 2.9 ± 0.44 nM/min; LPS-THP-1, 2.1 ± 0.32 nM/min, P = .019) suggesting more efficient APC function, probably as a consequence of the PCPS effect on APC cleavage at R306.74

When compared with bare tubes (Figure 4D), the contribution of LPS-THP-1 on fV activation and inactivation in the presence of EA.hy926 (Figure 5D) showed both an accelerated rate of activation (6.4 ± 0.6 nM/min vs 4.3 ± 0.6 nM/min, P = .035) and initial inactivation (2.1 ± 0.32 nM/min vs 0.39 ± 0.06 nM/min). The maximum concentrations of fVa formed differed slightly (with EA.hy926, 18.3 nM vs without EA.hy926, 20 nM), whereas the peak concentration occurred earlier with EA.hy926 (3 minutes vs 8 minutes, respectively). The faster rate of fVai307-506 formation with LPS-THP-1 activation with EA.hy926 compared with the same Tf source in bare tubes (2.1 ± 0.32 nM/min vs 0.39 ± 0.06 nM/min, P < .001) is illustrated by comparison of Figures 5D and 4D.

Table 2 summarizes the results of experiments with the 2 Tf sources with and without EA.hy926. The following differences stand out with respect to the combination of LPS-THP-1 in the presence of EA.hy926: 1) clot time is shorter, 2) the delayed rate of TAT generation observed with LPS-THP-1 in bare tubes is recovered to a rate equivalent to rTf in bare tubes, and 3) rTf gave a slower TAT generation rate with the endothelial cell surrogate. The ultimate accumulated level of thrombin induced by both Tf sources is reduced with the endothelial cell surrogate. The combination of monocyte and endothelial surrogates increases the rate of fV activation. The rate of fVa inactivation is accelerated with EA.hy926 with both Tf sources compared with bare tubes. A dramatic increase in the release of FPA is observed with a combination of LPS-THP-1 and EA.hy926 compared with all systems.

Reproducibility of the surrogate cell system

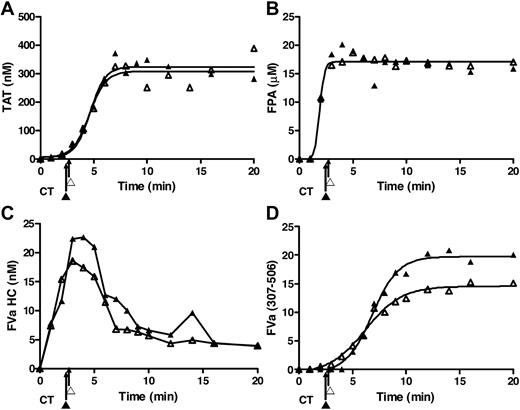

A primary objective of the present study was to develop reproducible endothelial and inflammatory monocyte surrogates to evaluate the individual phenotypic variations in blood composition and response to a Tf stimulus mimicking venous stasis with an activated inflammatory cell. To ensure that these data in the cohort study represented by the mean product formation over time are reproducible and would not mask the observations for a specific subject within the cohort, we compared data for 2 studies conducted 8 days apart for a single individual's blood evaluated using the monocyte/endothelial surrogate environment. Previous studies15,43 have shown that most individuals' blood is highly reproducible with respect to Tf stimulation in bare tubes. These data presented in Figure 6 illustrate that this is also true for a single subject when blood in contact with a surrogate endothelial cell layer is confronted with the surrogate monocyte Tf presentation. Presented are data for the 2 experiments conducted 8 days apart for generation of TAT, FPA, fVa HC, and the fVai APC degradation product 307-506. These data obtained for the single subject are reproducible over time and the surrogate inflammatory cell activator and vascular bed are representative of the population study presented in Figure 5.

Surrogate cell reproducibility. Data represent replicate of experiments for a single subject with EA.hy926 and LPS-THP-1 conducted on 2 occasions (▴, ▵) with an 8-day interval between experiments. These data illustrate the reproducibility of (A) TAT formation, (B) FPA formation, (C) fV activation, and (D) fVa inactivation in these duplicate experiments. These data show the reproducibility of the method with respect to the use of the 2 surrogates and also show these observations for the single subject are representative of those for the cohort.

Surrogate cell reproducibility. Data represent replicate of experiments for a single subject with EA.hy926 and LPS-THP-1 conducted on 2 occasions (▴, ▵) with an 8-day interval between experiments. These data illustrate the reproducibility of (A) TAT formation, (B) FPA formation, (C) fV activation, and (D) fVa inactivation in these duplicate experiments. These data show the reproducibility of the method with respect to the use of the 2 surrogates and also show these observations for the single subject are representative of those for the cohort.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that (1) the EA.hy926 cell line provides a stable endothelial cell surrogate presenting a complement of known coagulation-related endothelial cell surface proteins, which produces consistent anticoagulant responses suggestive of a functioning endothelium with Tf-activated phlebotomy blood; (2) LPS-THP-1 can function as a reproducible surrogate for a stimulated circulating cell source of Tf; (3) EA.hy926 and LPS-THP-1 provide a reasonable surrogate for venous stasis coupled with a blood derived inflammatory stimulus; and (4) there appears to be a cooperative cell-cell effect between EA.hy926 and an LPS-THP-1, not seen when rTf/PCPS is used as the activator.

The activation of blood by rTf/PCPS versus LPS-THP-1 produces very different coagulation profiles with EA.hy926 including: faster and greater thrombin formation, increased fVa generation, and increased rate of FPA release. Complete fVa inactivation (fVai307-506 generation) is faster in the presence of EA.hy926 regardless of the Tf source illustrating the presence of a functional TM-EPCR protein C activation system.19,72 In contrast, in the absence of EA.hy926, blood clotting times with both Tf sources are similar as are FPA release and fV activation and inactivation, although thrombin is generated at a slower rate during the propagation phase with LPS-THP-1.

EA.hy926 and LPS-THP-1 correspond to reproducible surrogates for the known procoagulant and anticoagulant functions displayed by endothelial cells presenting similar concentrations of VWF, TM, EPCR, and TFPI. The principle reason for using these cells as surrogates for the respective natural cells is because of the variability of the cells from natural sources,75-81 which in combination with the high variability of human donor blood would lead to uninterpretable data. The reproducibility problem for endothelial cells from various natural sources and from passage to passage is well documented. EA.hy926 appears to provide endothelial cell–like function with respect to APC anticoagulation.

LPS stimulation of monocytes has been reported to elicit the secretion of TNF-α and interleukin-1, which may modify the function of endothelium.82 Furthermore, simultaneous thrombin and LPS stimulation of monocytes increases the release of TNF-α and interleukin-1β.82 In the present study, we observe that although EA.hy926 Tf expression is not detectable via LPS administration, the significant differences observed for LPS-THP-1 with or without EA.hy926 suggest a cooperative process between the surrogate inflammatory cell and the surrogate endothelium. However, TNF-α–induced expression of Tf is an unlikely mechanism because Tf surface expression occurring 3 minutes after stimulation could not occur via de novo synthesis and Tf is not stored within the cell. The increase in EA.hy926–LPS-THP-1 procoagulant activity potentially may provide in vitro experimental access to the relationship between sepsis, inflammation, and coagulation. These data suggest that stimulated monocytes may directly activate or intensify the endothelial inflammatory phenotype and contribute to vascular thrombosis.

A finding replicated in the present study related to whole-blood activation by Tf is the absence of quantitative conversion of prothrombin to thrombin. In addition, a significant fraction of thrombin B chain escapes covalent association with antithrombin. The laboratory of Dr Hemker83 identified that a significant fraction of thrombin is bound to α2-macroglobulin, and our studies suggest accumulation of the thrombin α1-antitrypsin complex.84 Furthermore, significant destructive prothrombin cleavage by thrombin leads to production of prothrombin fragment 1 and prethrombin 1.

The use of these 2 transformed cell lines provides a reproducible method to evaluate the variations in blood phenotype against the background of stable blood cell activator and vascular endothelial surrogates. The EA.hy926–LPS-THP-1 system thus provides a useful method for characterizing the biochemical dynamics of how an individual's blood would respond to an inflammatory cell presented Tf under conditions of venous stasis.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Whelihan and Daniel LaJoie for technical assistance and Dr Thomas Orfeo for intellectual input. We thank Jolanta Amblo for technical assistance and expertise in immunochemical assays and Dr Jeffrey Spees and Marilyn Wadsworth for assistance with confocal microscopy. Special thanks to Winifred Trotman for expertise in fluorescent confocal microscopy image capture for comparative analysis of EA.hy926 cells and HUVECs and to Dr Beth Bouchard for use of laboratory equipment and intellectual input.

This study was supported by grants P01 HL46703 and T32 HL07594 by the National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.E.C. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the paper; K.E.B.-Z. designed research, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the paper; S.B. performed research and contributed to the writing of the paper; and K.G.M. contributed to experimental design, analytical tools, data analyses, and the writing of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.G.M. is Chairman of the Board of Haematologic Technologies. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kenneth G. Mann, PhD, Department of Biochemistry, Colchester Research Facility Rm 235, University of Vermont, Colchester, VT 05446; e-mail: kenneth.mann@uvm.edu.